This is “Aromatic Compounds: Benzene”, section 13.7 from the book Introduction to Chemistry: General, Organic, and Biological (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

13.7 Aromatic Compounds: Benzene

Learning Objective

- Describe the bonding in benzene and the way typical reactions of benzene differ from those of the alkenes.

Next we consider a class of hydrocarbons with molecular formulas like those of unsaturated hydrocarbons, but which, unlike the alkenes, do not readily undergo addition reactions. These compounds comprise a distinct class, called aromatic hydrocarbonsA hydrocarbon with a benzene-like structure., with unique structures and properties. We start with the simplest of these compounds. Benzene (C6H6) is of great commercial importance, but it also has noteworthy health effects (see “To Your Health: Benzene and Us”).

The formula C6H6 seems to indicate that benzene has a high degree of unsaturation. (Hexane, the saturated hydrocarbon with six carbon atoms has the formula C6H14—eight more hydrogen atoms than benzene.) However, despite the seeming low level of saturation, benzene is rather unreactive. It does not, for example, react readily with bromine, which, as mentioned in Section 13.1 "Alkenes: Structures and Names", is a test for unsaturation.

Note

Benzene is a liquid that smells like gasoline, boils at 80°C, and freezes at 5.5°C. It is the aromatic hydrocarbon produced in the largest volume. It was formerly used to decaffeinate coffee and was a significant component of many consumer products, such as paint strippers, rubber cements, and home dry-cleaning spot removers. It was removed from many product formulations in the 1950s, but others continued to use benzene in products until the 1970s when it was associated with leukemia deaths. Benzene is still important in industry as a precursor in the production of plastics (such as Styrofoam and nylon), drugs, detergents, synthetic rubber, pesticides, and dyes. It is used as a solvent for such things as cleaning and maintaining printing equipment and for adhesives such as those used to attach soles to shoes. Benzene is a natural constituent of petroleum products, but because it is a known carcinogen, its use as an additive in gasoline is now limited.

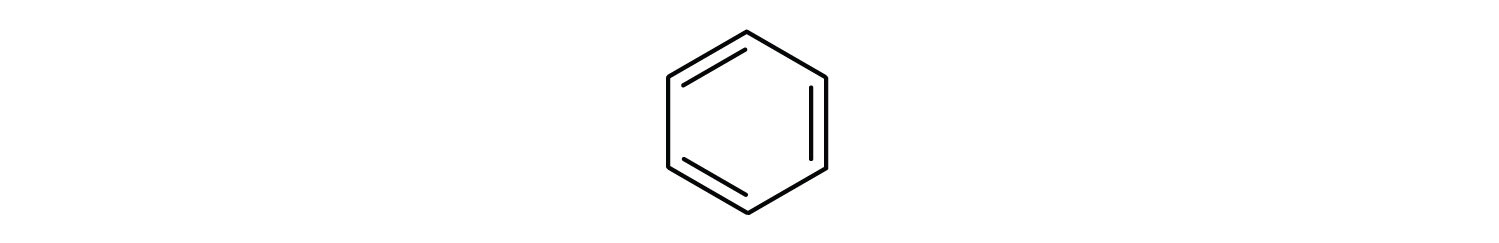

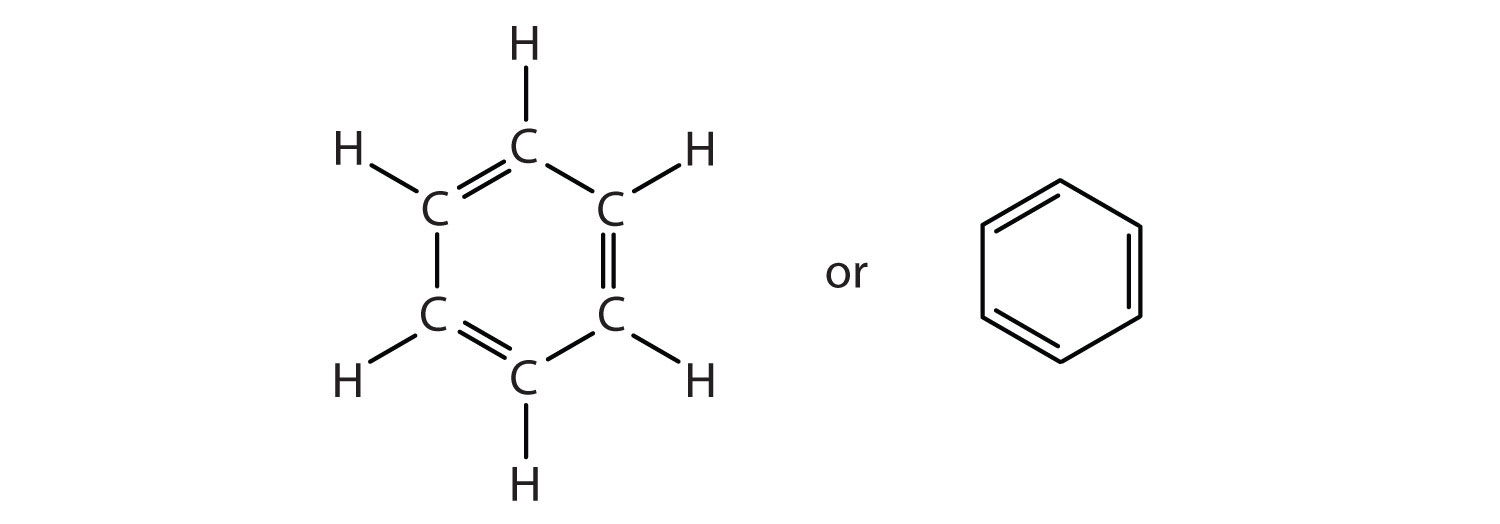

To explain the surprising properties of benzene, chemists suppose the molecule has a cyclic, hexagonal, planar structure of six carbon atoms with one hydrogen atom bonded to each. We can write a structure with alternate single and double bonds, either as a full structural formula or as a line-angle formula:

However, these structures do not explain the unique properties of benzene. Furthermore, experimental evidence indicates that all the carbon-to-carbon bonds in benzene are equivalent, and the molecule is unusually stable.

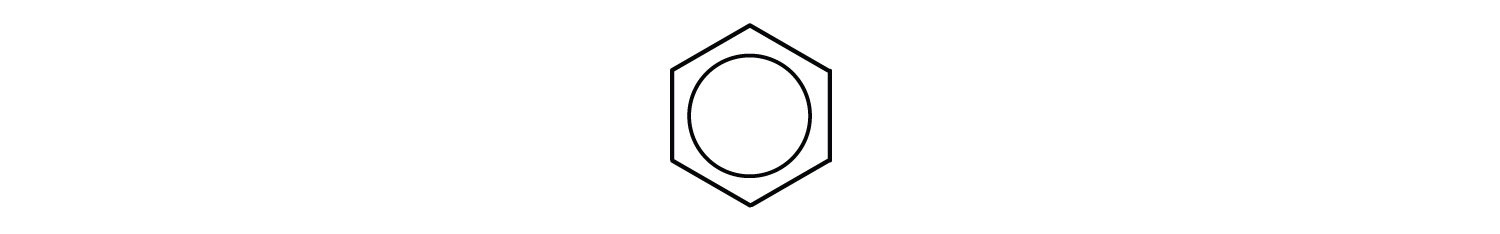

Chemists often represent benzene as a hexagon with an inscribed circle:

The inner circle indicates that the valence electrons are shared equally by all six carbon atoms (that is, the electrons are delocalized, or spread out, over all the carbon atoms). It is understood that each corner of the hexagon is occupied by one carbon atom, and each carbon atom has one hydrogen atom attached to it. Any other atom or groups of atoms substituted for a hydrogen atom must be shown bonded to a particular corner of the hexagon. We use this modern symbolism, but many scientists still use the earlier structure with alternate double and single bonds.

To Your Health: Benzene and Us

Most of the benzene used commercially comes from petroleum. It is employed as a starting material for the production of detergents, drugs, dyes, insecticides, and plastics. Once widely used as an organic solvent, benzene is now known to have both short- and long-term toxic effects. The inhalation of large concentrations can cause nausea and even death due to respiratory or heart failure, while repeated exposure leads to a progressive disease in which the ability of the bone marrow to make new blood cells is eventually destroyed. This results in a condition called aplastic anemia, in which there is a decrease in the numbers of both the red and white blood cells.

Concept Review Exercises

-

How do the typical reactions of benzene differ from those of the alkenes?

-

Briefly describe the bonding in benzene.

-

What does the circle mean in the chemist’s representation of benzene?

Answers

-

Benzene is rather unreactive toward addition reactions compared to an alkene.

-

Valence electrons are shared equally by all six carbon atoms (that is, the electrons are delocalized).

-

The six electrons are shared equally by all six carbon atoms.

Key Takeaway

- Aromatic hydrocarbons appear to be unsaturated, but they have a special type of bonding and do not undergo addition reactions.

Exercises

-

Draw the structure of benzene as if it had alternate single and double bonds.

-

Draw the structure of benzene as chemists usually represent it today.