This is “The Victorian Era”, chapter 7 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 7 The Victorian Era

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

7.1 The Victorian Era (1832–1901)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize and evaluate the influence that Queen Victoria and Prince Albert exerted on the last half of the 19th century.

- Identify and explain the conflicts that defined the Victorian Era.

- Assess the ways in which these conflicts influenced Victorian literature.

- List, define, and give examples of typical forms of Victorian literature.

Snow Hill, Holburn, London (Anonymous).

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…”

Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

The Victorian Age—the era when the sun never set on the British Empire, a time when the upper classes of Britain felt their society was the epitome of prosperity, progress, and virtue—Dickens’s words, however, could apply to his own Victorian age as well as they apply to the French Revolution setting of his novel. The Victorian Era was a time of contrasts—poverty as well as prosperity, degrading manual labor as well as technological progress, and depravity as well as virtue.

Queen Victoria

The last seventy years of the 19th century were named for the long-reigning Queen Victoria. The beginning of the Victorian Era may be rounded off to 1830 although many scholars mark the beginning from the passage of the first Reform Bill in 1832 or Victoria’s accession to the throne in 1837.

Victoria was only eighteen when her uncle William IV died and, having no surviving legitimate children, left the crown to his niece.

Victoria receives the news that she is Queen. Engraved by Emery Walker (1851–1933), from the picture by Henry Tanworth Wells (1828–1903) at Buckingham Palace.

Although by the 19th century Britain was a constitutional monarchy and the queen held little governing power, Victoria set the moral and political tone of her century. She became a symbol of decency, decorum, and duty.

Three years into her reign, Victoria married Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, a region in what is now Germany. Prince Albert (given the title “Prince” by Victoria), although he had no actual power in the government, became one of Victoria’s chief advisors and a proponent of technological development in Britain. Together the couple had nine children who married into many of Europe’s royal and noble families. Victoria and Albert were considered the model of morality and respectable family life.

Balmoral Castle, the royal residence in Scotland.

Osborne House, the royal residence on the Isle of Wight.

When Prince Albert died in 1861, Victoria retired from public view, spending time in her Balmoral Castle in Scotland or Osborne House on the Isle of Wight. Public opinion of the queen waned as years passed without her resuming her official duties. Even when she conceded to her advisors’ urging to return to London and to honor her public obligations, she continued to wear mourning until her own death. She also commissioned many public memorials to Prince Albert, including the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park (near the original location of the Crystal Palace), Royal Albert Hall, and the Victoria & Albert Museum.

The Albert Memorial, Hyde Park, London.

Royal Albert Hall, London.

The ornamental dome on the Victoria & Albert Museum was modeled after Queen Victoria’s favorite crown, visible in the portrait below, now on display with the Crown Jewels at the Tower of London.

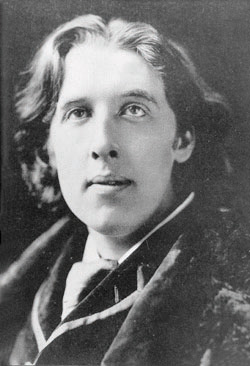

Photograph by Alexander Bassano 1829–1913.

Queen Victoria reigned as Queen of the United Kingdom and Empress of India until her death in 1901.

Victorian Conflicts

The Victorian Era was, in many ways, paradoxically “the best times” and “the worst of times.”

Conflicts of Morality

Queen Victoria embodied ideals of virtue, modesty, and honor. In fact, the term Victorian has in the past been almost a synonym for prim, prudish behavior. At the same time, London and other British cities had countless gaming halls which provided venues not just for gambling but also opium dens and prostitution. With the influx of population into the cities, desperate working class women turned to prostitution in attempts to support themselves and their children. Historian Judity Walkowitz reports that 19th century cities had 1 prostitute for every 12 adult males (quoted in “The Great Social Evil”: Victorian Prostitution by Prof. Christine Roth). Because of rampant sexually transmitted diseases among the British military, Parliament passed a series of Contagious Diseases Acts in the 1860s. These acts allowed police to detain any woman suspected of having a sexually transmitted disease and to force her to submit to exams that were considered humiliating for women at that time. Police needed little basis for such suspicions, often simply that a woman was poor.

Thomas Hardy’s poem “The Ruined Maid” reveals one reason many women turned to prostitution (ruined is a Victorian euphemism for an unmarried woman who has lost her virginity): in the poem, two young women converse. One woman, Melia, has left the farm to become a prostitute. When she meets a former friend, the contrast between the two women is pronounced: Melia is wearing fine clothes and is well fed and well cared for. The virtuous young woman, doing honest work on the farm, is wearing rags, digging potatoes by hand for subsistence, and suffering poor health. Hardy forces his readers to question what kind of society would reward prostitution while leaving the virtuous woman in abject poverty.

Conflicts of Technology and Industry

As an advocate of Victorian progress in science and industry, Prince Albert commissioned the Great Exhibition of 1851, a type of world’s fair where all the countries in the British Empire had displays and Britain could show off its prosperity to the rest of the world. Albert had the Crystal Palace, a huge, modern building of glass and iron, built in Hyde Park to house the exhibition. After the Great Exhibition ended, the building was dismantled and moved and in its new location was destroyed by fire in 1936.

Video Clip 1

The Albert Memorial Symbol of the Victorian Age

(click to see video)View a video lecture about the Albert Memorial.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 held in the Crystal Palace, Hyde Park, London.

Source: Exterior: from Dickinson's Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851, 1854 interior: William Simpson (lithographer), Ackermann & Co. (publisher), 1851, V&A.

The Albert Memorial commemorated all the same things the Great Exhibition vaunted. The four arms extending from the main statue represent four continents on which the British Empire had holdings: Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas—the sun literally never set on the British Empire. The figures on the frieze are great painters, poets, sculptors, musicians, and architects, representatives of the world’s accomplishments which culminated in the British Victorian culture. The mosaics on the canopy represent manufacturing, commerce, agriculture, and engineering—the foundations of British prosperity. And, of course, in the center, is the gilded figure of Albert himself.

Arm representing Africa.

Prince Albert’s Great Exhibition of 1851 focused attention on the technological advances made during the Industrial Revolution. Although achievements such as the building of the railroad system and the implementation of mechanized factories produced great prosperity for some, others suffered. Even before the Victorian Era, writers drew attention to these problems. Wordsworth’s “Michael,” for example, portrays a man whose family had made their living from their land for many generations. With the advent of machines to weave woolen cloth, their livelihood, their way of life, was lost. Blake’s “Chimney Sweeper” poems illustrate how children suffered in the industrial age.

A girl pulling a coal tub in a mine.

Source: Parliamentary Papers 1842.

In addition, working conditions in factories were deplorable. With no safety regulations and no laws limiting either the number of hours people could be required to work or the age of factory workers, some factory owners were willing to sacrifice the well-being of their employees for greater profit. Children as young as five worked in factories and mines. Shelley’s “Men of England” and Barrett Browning’s “The Cry of the Children” are two examples of poems written specifically to address these problems.

The 1833 Factory Act outlawed the employment of people under age eighteen at night, from 8:30 p.m. to 5:30 a.m. and limited the number of hours those under eighteen could work to twelve hours a day. For the first time, textile factory owners were forbidden to employ children under the age of nine. Children under age eleven could not work more than nine hours a day. The 1833 Factory Act also stipulated that children working in factories attend some type of school.

The Mines Act of 1842 prohibited females and boys under ten from working below ground in mines.

While these provisions hardly seem protective according to modern standards, the resulting conditions greatly improved life for many children. Throughout Victoria’s reign, other parliamentary acts continued to alleviate working conditions in the ever-expanding Victorian industrial age.

Conflicts of Faith and Doubt

The scientific and technological advances celebrated at the Great Exhibition of 1851 led to another crisis in Victorian England: a crisis of faith and doubt. During the earlier part of the 19th century, the work of Charles Lyell and other geologists with their discoveries of fossilized remains of animals never seen before led to debates among scientists about the origins of these creatures. Debates about the age of the earth for some called into question the Genesis account of creation. In 1859, Charles Darwin published his On the Origin of Species. Lyell and Darwin were among many who contributed to scientific theories that some saw as contradictory to established religious beliefs.

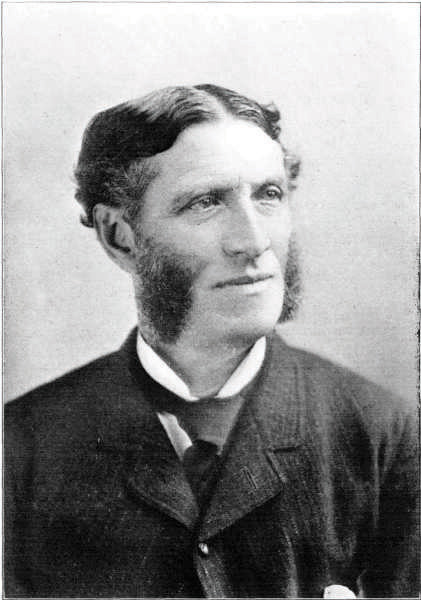

These scientific issues together with apparent lack of concern for appalling human conditions among the lower classes led some to doubt the presence of a divine being in the world and others to question the value of Christianity. Literature by writers such as Thomas Hardy and Matthew Arnold questions the presence of religious faith in the world.

At the same time, a conviction that Britain had a duty to spread Christianity around the world became one reason, or to some an excuse, for British imperialism.

Conflicts over Imperialism

A desire to expand industrial wealth and to have access to inexpensive raw materials led to the British occupation of countries around the globe. Although the United States and other European countries participated in this type of imperialism, the British Empire was the largest and wealthiest of its time.

Along with their desire for material gain, many British saw the expansion of the British Empire as what Rudyard Kipling referred to as “the white man’s burden,” the responsibility of the British to bring their civilization and their way of life to what many considered inferior cultures. The result of this type of reasoning was often the destruction of local cultures and the oppression of local populations. In addition, a religious zeal to bring British religion to “heathen” peoples resulted in an influx of missionaries with the colonialists.

A backlash of protest against the concept of imperialism further divided a British nation already divided by class, religion, education, and wealth. While many British citizens sincerely desired to share their knowledge and beliefs with less developed nations, others found the movement a convenient excuse to expand their country’s, and their own, power and wealth.

Conflicts over Women’s Rights

“The Queen is most anxious to enlist everyone who can speak or write to join in checking this mad, wicked folly of ‘Woman’s Rights,’ with all its attendant horrors, on which her poor feeble sex is bent, forgetting every sense of womanly feeling and propriety.”Queen Victoria, 1870

quoted in Lytton Strachey’s Queen Victoria)

Ironically, as seen in this passage from a letter written in the royal third person by Queen Victoria, even the Queen opposed women’s rights. Nonetheless, the Victorian Era did see advancement in women’s political rights. The Married Woman’s Property Act of 1870 gave married women the right to own property they earned or acquired by inheritance. The upper classes were, of course, primarily concerned with inheritances. Before the passage of this act, money or property left to a married woman immediately belonged to her husband. By the late 19th century, women had some rights to their children and the right to leave their husbands because of physical abuse.

Education for women also improved. The idea Mary Wollstonecraft expressed in her “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman” in 1792 very gradually, over more than 100 years, became a reality.

The first schools for the lower classes, girls or boys, were Sunday schools organized by churches to teach children basic literacy as well as religious lessons on the only day they were not working full time. Not until the Education Act of 1870 were public schools in all areas of the country provided by law. Even then, attendance was not made compulsory for another ten years and then only for children aged five to ten.

A 19th century Sunday school.

Girls from the lower classes were included in the first public schools; however, girls from the upper classes continued to receive their basic education primarily in the home and in finishing schools for young ladies. Cambridge University and Oxford University established the first colleges for women in the latter half of the 19th century. Women were not allowed to attend the existing colleges for men and were not considered full members of the universities until the 20th century.

Although there was an active woman’s suffrage movement during the Victorian Era, women did not receive the right to vote until the 20th century.

Take the Women’s Rights Quiz on the BBC website to see how much you know about the rights of Victorian women.

Language

The major change in the English language during the 19th century was the introduction of vocabulary to communicate new innovations, inventions, and concepts that resulted from the Industrial Age. Language mirrored class distinctions in both vocabulary and accents. The well educated upper classes were distinguished by their speech. Slang and an entirely differently accented English were the marks of the lower classes.

Forms of Literature

Novel

As noted in the Romantic Period introduction, a novelAs defined in the Holman/Harmon Handbook to Literature, an “extended fictional prose narrative.”, as defined in the Holman/Harmon Handbook to Literature, is an “extended fictional prose narrative.” The novel was a dominant form in the Victorian Era. Many Victorian novelists—Charles Dickens, William Thackeray, Wilke Collins, George Eliot, Robert Louis Stevenson—wrote serial novelsNovels published in installments over a period of time., novels published in installments over a period of time. Serial novels appeared in newspapers or magazines or could be published in independently printed booklets. As larger portions of the population became literate, demand for reading material grew. The inexpensive booklets, each containing a chapter or other small portion of a novel, were affordable entertainment for the middle classes.

Poetry

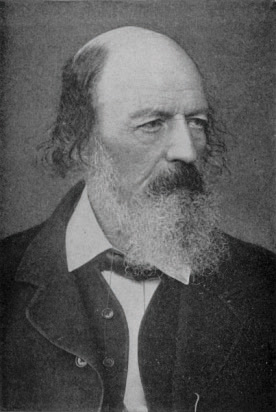

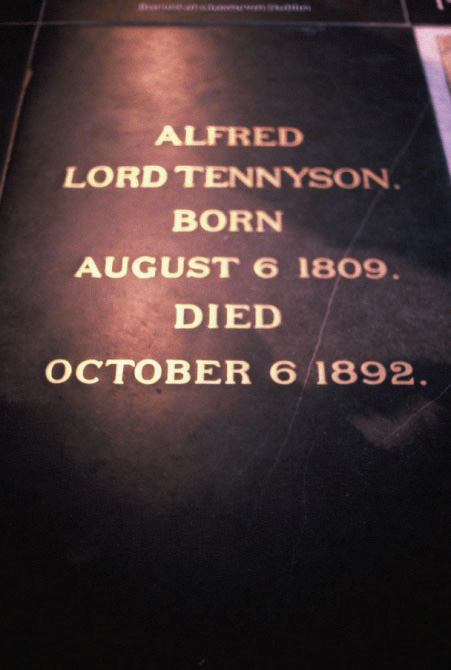

As in the Romantic Period, lyric poetry was popular in the Victorian Era. In addition to the lyric, the verse novelA long narrative poem., a long narrative poem, such as Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh, Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, and Browning’s The Ring and the Book, also was a prevalent form. Browning popularized the dramatic monologueA form of poetry which presents a speaker in a dramatic situation., a form of poetry which presents a speaker in a dramatic situation.

Non-Fiction Prose

The many conflicts of the Victorian Era provided fertile subject matter for non-fiction prose writers such as Matthew Arnold, Thomas Carlyle, John Stuart Mill, John Henry Newman, Walter Pater, and John Ruskin.

Drama

Popular forms of entertainment such as the music hall and melodramas flourished during the Victorian Era as entertainment became divided along class lines. Popular music and musical plays, separated from legitimate theater in their own venues, provided leisure-time amusement for the middle classes. Robert Browning wrote closet dramasPlays not actually intended for the stage., plays not actually intended for the stage. Oscar Wilde revived the comedy of manners with plays such as Lady Windermere’s Fan and The Importance of Being Earnest.

Key Takeaways

- Although Queen Victoria symbolized decency, decorum, and duty, Victorian society spanned a wide spectrum of prosperity and poverty, education and ignorance, progress and regression

- Victorian society wrestled with conflicts of morality, technology and industry, faith and doubt, imperialism, and rights of women and ethnic minorities.

- Many Victorian writers addressed both sides of these conflicts in many forms of literature.

- Typical forms of Victorian literature include novels, serialized novels, lyric poetry, verse novels, dramatic monologues, non-fiction prose, and drama.

Resources

Victorianism

- “All Change in the Victorian Age.” Bruce Robinson. Britain’s Industrial Revolution. Victorians. BBC History.

- “Monuments and Dust: The Culture of Victorian London.” Michael Levenson, University of Virginia; David Trotter, University College London; Anthony Wohl, Vassar College. Institute for Advance Technology in the Humanities, University of Virginia; Department of English University College London; Cambridge University Press.

- “Movements and Currents in Nineteenth-Century British Thought.” The Victorian Web. George P. Landow, Brown University.

- “Overview of the Victorian Era.” History in Focus. Anne Shepherd. University of London.

- “Victorian and Victorianism.” The Victorian Web. George P. Landow, Brown University.

- “Victorian Britain.” History Trails. BBC.

- “Victorian England: An Introduction.” Christine Roth, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh.

- “The Victorian Period.” Dr. Robert M. Kirschen, University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

- “Victorians 1837–1901.” Liza Picard. The British Library.

- “Victorians 1850–1901.” The National Archives.

Queen Victoria

- “Queen Victoria.” The Victorian Web. David Cody, Hartwick College.

Victorian Conflicts

Conflicts of Morality

- “Addiction in the Nineteenth Century.” Dr. Susan Zieger, Stanford University.

- “The Contagious Diseases Act.” The Victorian Web.

- “The Great Social Evil”: Victorian Prostitution. Prof. Christine Roth, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh.

- “Opium Dens and Opium Usage in Victorian England.” Victorian History. Bruce Rosen, University of Tasmania.

Conflicts of Technology and Industry

- “1832 Reform Act.” Taking Liberties: The Struggle for Britain’s Freedoms and Rights. The British Library.

- “The 1833 Factory Act [from Statutes of the Realm, 3 & 4 William IV, c. 103].” The Victorian Web. Dr. Marjie Bloy, National University of Singapore.

- “19th Century Poor Law Union and Workhouse Records.” The National Archives. brief explanation of 1834 Poor Law and images.

- “Child Labor.” The Victorian Web. David Cody, Hartwick College.

- “Corn Laws.” The Victorian Web. David Cody, Hartwick College.

- “The Crystal Palace Animation.” The Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities. University of Virginia.

- “The Crystal Palace, or The Great Exhibition of 1851: An Overview.” The Victorian Web.

- “Great Exhibition.” Treasures. The National Archives.

- “The Great Exhibition.” History, Periods & Styles Features. The Victoria & Albert Museum.

- “The Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace.” Victoria Station.

- “The Life of the Industrial Worker in Nineteenth-Century England.” The Victorian Web. Laura Del Col, West Virginia University.

- “The Reform Acts.” The Victorian Web. Glenn Everett, University of Tennessee at Martin.

- “Testimony Gathered by Ashley’s Mines Commission.” The Victorian Web. Laura Del Col, West Virginia University.

Conflicts of Faith and Doubt

- “Victorian Science & Religion.” The Victorian Web. Aileen Fyfe, National University of Ireland Galway and John van Wyhe, Cambridge University.

Conflict over Imperialism

- “The British Empire.” The Victorian Web. David Cody, Hartwick College.

- “British Empire.” The National Archives.

- “Kipling’s Imperialism.” The Victorian Web. David Cody, Hartwick College.

Conflicts over Women’s Rights

- “The 1870 Education Act.” Living Heritage: Going to School. www.parliament.uk.

- “Gender Ideology & Separate Spheres.” Gender, Health, Medicine & Sexuality in Victorian England. Victoria & Albert Museum.

- “Gender Matters.” The Victorian Web.

- “The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies.” The Victorian Web. Helena Wojtczak.

- “‘The Personal is Political’: Gender in Private & Public Life.” Gender, Health, Medicine & Sexuality in Victorian England. Victoria & Albert Museum.

- “The Suffragettes in Parliament.” History of Parliament Podcasts. www.parliament.uk.

- “Suffragists.” Learning: Dreamers and Dissenters. The British Library.

- “Victorian Britain: A Divided Nation?” Education. The National Archives.

- “Women’s Status in Mid 19th-Century England: A Brief Overview.” Helena Wojtczak. Hastings Press.

- “Women’s Rights Quiz.” Major Events of Victoria’s Reign. Victorians. BBC History.

- “Women’s Work.” Prof. Pat Hudson, Cardiff University. Daily Life in Victorian Britain. Victorians. BBC History.

Victorian Language

- “The Development of the English Language Following the Industrial Revolution.” The Victorian Web. Jessica Courtney, University of Brighton (UK).

Literature

- “The 19th Century Novel.” Novels. Dr. Agatha Taormina, Extended Learning Institute of Northern Virginia Community College.

- “Gerard Manley Hopkins and the Difficulties of Victorian Poetry.” The Victorian Web. George P. Landow, Brown University.

- “Justifying God’s Ways to Man (and Woman): The Victorian Long Poem.” The Victorian Web. George P. Landow. Brown University.

- “Literary Genre, Mode, and Style.” The Victorian Web.

- “Nineteenth Century Drama.” Theatre Database.

- “Progress of Journalism in the Victorian Era.” Bartleby.com. The Growth of Journalism. rpt. from The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21). Vol. XIV. The Victorian Age, Part Two.

- “Serial Publication.” Prof. Joel J. Brattin, Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Dickens. Life and Career. PBS.org.

- Some Questions to Use in Analyzing Novels. Prof. Stephen C. Behrendt, University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

- “Studies of Victorian Literature.” Dr. John P. Farrell, University of Texas at Austin.

- “Victorian Literature and Culture.” Prof. James Buzard. MIT Open Courseware.

- “Victorian Serial Novels.” Digital Collections. University of Victoria Libraries.

- “Victorian Women Writers Project.” University of Indiana Digital Library Project.

- “Why Read the Serial Versions of Victorian Novels?” The Victorian Web. Philip V. Allingham, Lakehead University.

Video

- “The Albert Memorial: Symbol of the Victorian Age.” Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.

- “The Great Exhibition.” Victorians. The British Library.

- “The Rise of Technology and Industry.” Learning: Victorians. The British Library. images, slide shows, video, podcasts featuring all types of industry and technological advances in daily life, such as cooking and bathrooms.

Audio

- “A Visitor’s Guide to the Great Exhibition, from ‘The Illustrated Exhibitor.’” The Great Exhibition. Victorians. The British Library.

7.2 Charles Dickens (1812–1870)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize A Tale of Two Cities as a serial novel, and account for the popularity of serial novels in Victorian England.

- Evaluate the role of the novel’s structure in conveying themes.

- Define and illustrate the use of literary devices such as anaphora, asyndeton, parallelism, and paradox in the novel’s famous opening lines.

- Distinguish developing characters from static characters and analyze the purpose of each.

- List and provide specific examples from the text of significant themes and images.

Biography

Dickens’s birthplace in Portsmouth.

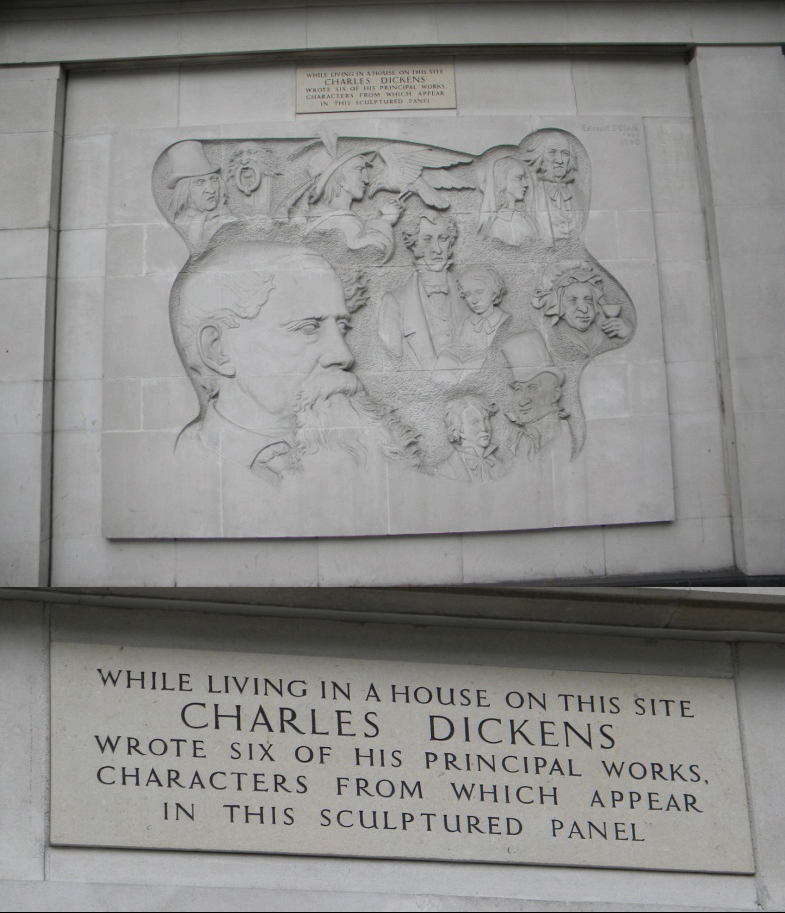

Charles Dickens was born in 1812 in Portsmouth, a major port city in England. Although Dickens’s father worked as a clerk in a Navy office, he accrued debt and was imprisoned in Marshalsea Prison in London. Dickens’s mother and siblings joined him in prison, but at age twelve, Dickens went to work in a boot blacking factory in London to help support his family. The experiences he had there provided material for many of his novels that depict the working poor of London.

Forty-eight Doughty Street, the only surviving London house Dickens lived in. He was living here when he wrote Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby.

When his father was released from prison, Dickens was able to attend school and eventually worked as an office assistant for an attorney, a position which led to his becoming a court reporter, a reporter in Parliament, and eventually a journalist. With the success of his first serialized novel, Pickwick Papers, Dickens became a full-time novelist. His novels quickly achieved mass popularity, audiences eagerly awaiting new installments of the serial novels. Always interested in the theatre, Dickens conducted a series of public readings of his novels, drawing large enthusiastic audiences in England, on the continent, and in America. The readings added to his fame but later in life proved harmful to his health. Against his doctor’s advice, he completed a final reading tour in America and several more readings in England until he died of a stroke in 1870. Not surprisingly for a writer of his prominence, he was buried in Poet’s Corner at Westminster Abbey.

Text

- Dickens, Charles, 1812–1870. A Tale of Two Cities. Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library.

- A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens. Project Gutenberg.

- A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens. A. L. Burt Company, Publishers, New York. 1890. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

A Tale of Two Cities

Background

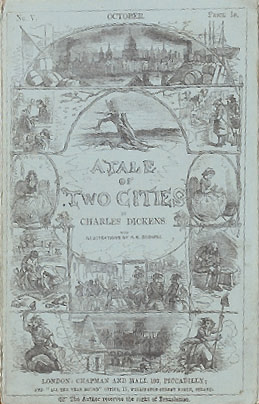

Published in 1859, A Tale of Two Cities is an example of a serial novel, a novel published in installments over a period of time. The novel was first published in weekly installments and again later in monthly installments.

Cover of the serial volume of A Tale of Two Cities with artwork by Hablot Knight Browne, known as Phiz, who illustrated many of Dickens’s works.

Fears that England might be heading toward a revolution like the French Revolution persisted into the Victorian Era. Literary references to these fears appear in many 19th-century works including Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest; Barrett Browning’s “The Cry of the Children,” Shelley’s “Men of England,” and Byron’s Don Juan.

The passage of Reform Bills in 1832, 1867, and 1884 to extend voting rights evidences the discontent of the previously disenfranchised working class and the unease of the upper classes who feared open rebellion.

Structure

A Tale of Two Cities is divided into three sections:

- Book the First: Recalled to Life (1775)

- Book the Second: The Golden Thread (1780–1789)

- Book the Third: The Track of a Storm (1792–1793)

Setting

“Chapter 1 The Period” begins with these well-known lines:

It was the best of times,

it was the worst of times,

it was the age of wisdom,

it was the age of foolishness,

it was the epoch of belief,

it was the epoch of incredulity,

it was the season of Light,

it was the season of Darkness,

it was the spring of hope,

it was the winter of despair…

Although these lines do little to depict the actual setting, they provide a hint of the contrasts the novel develops, contrasts of normal life and the Reign of Terror, innocence and guilt, life and death. Dickens makes the lines poetic and memorable with the use of literary devices:

- AnaphoraLines which begin with the same word or phrase.. Lines which begin with the same word or phrase (it was, it was, it was…)

- AsyndetonDeletion of conjunctions between sentences or clauses.. Deletion of conjunctions between sentences or clauses

- ParallelismThe use of the same grammatical structure for ideas of equal importance.. The use of the same grammatical structure for ideas of equal importance

- ParadoxThe juxtaposition of seemingly contradictory ideas.. The juxtaposition of seemingly contradictory ideas

To introduce the period in which the novel is set, Chapter 1 moves from these lines to more specific paragraphs which establish the places (Paris and London), the time (1775), and the atmosphere (foreboding). The last lines of Chapter 1 refer to the road of destiny and provide a transition to a literal road: the mail on the road to Dover. And thus the story begins.

Characters

- Sydney Carton. Carton is described as virtually dead, “like one who died young.” He may be seen as a Byronic hero, a dark, brooding anti-hero, aware of the profligate path in life he chooses. However, he is also a redemptive figure connected to resurrection imagery—life through death—and to prophecy.

- Charles Darnay. Unlike Carton and Dr. Manette, Darnay is a static character, exemplifying the Victorian ideal of the nature of nobility—he is nobly born and chooses to act nobly.

- Dr. Manette. Dr. Manette is the most vivid example of the theme of resurrection and redemption, particularly the redeeming capacity of love. Readers learn that Dr. Manette had been a man of strength and character but has been driven to madness by the evils he endures in France. Rescued and brought to England, a place of safety and sanity, he recovers because of Lucie’s loving care and is transformed into a strong, decisive character capable of planning and implementing a daring rescue.

- Lucie. The name Lucie is from the Latin root lux, meaning light, and her character exudes goodness, symbolized by light. She occupies one end of the good-evil spectrum. Like Darnay, Lucie is a static, flat character, a stereotypical Victorian upper class woman.

- Madame DeFarge. Madame DeFarge is the other end of the good-evil spectrum although she has an explanation for her evil and desire for revenge. The image of Madame DeFarge knitting is, in addition to being one of the most famous images in British literature, the central image of the novel. Her knitting intimates the archetypal image of weaving to represent the threads of life, as suggested in the title of Part II, The Golden Thread.

- Ernest DeFarge. With a name signifying his role, Ernest DeFarge serves as a comparison and contrast with Madame DeFarge

- The Vengeance. The Vengeance is an allegorical characterA character who represents an abstract quality, creating two levels of meaning in a literary work., a character who represents an abstract quality, creating two levels of meaning in a literary work.

- Miss Pross. As Lucie is a stereotype of an upper class British woman, Miss Pross is a stereotype of a British working class woman, loyal and fiercely patriotic.

- Cruncher. The inclusion of a “resurrection man” amplifies, and in a subtle way satirizes, the theme of resurrection.

Cities as Characters

The title declares the story a tale of two cities. Paris and London become conveyances of theme: light and dark, good and evil, redemption and retribution.

Portraying London as a place of safety, of survival, even of sanity resonated with patriotic Victorian audiences, contributing to pride in the British Empire.

Themes

- Threads of destiny. The weaving or knitting motif serves as an archetypeAn image or symbol embedded in the collective unconsciousness of people from all cultures, an idea based on the psychological theory of Carl Jung., an image or symbol embedded in the collective unconscious of people from all cultures, an idea based on the psychological theory of Carl Jung. In mythology, the Fates weave, representing fate determining human destiny, gradually revealing the pattern of one’s life in their tapestry.

- Guilt and retribution. The French aristocracy is personified in St. Evrémondes, who in turn personifies guilt. Darnay is inextricably connected to the guilt as surely as he is related to St. Evrémondes, an example of the weaving together of various threads to form one’s destiny. Retribution is embodied in Madame DeFarge.

- Retribution and redemption. The contrast of retribution and redemption form a major theme of the novel, a theme in which almost all the characters play a role.

- The doppelganger. The word doppelganger, translated from German, literally means ‘double walker” or “double goer.” In folklore, the doppelganger is often a harbinger of death or an ill omen, not necessarily a physical double. Elements of the doppelganger in both senses function in A Tale of Two Cities.

Key Takeaways

- Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities was published as a serial novel, a popular form of publication in the Victorian Era.

- The novel is structured in three parts, each part with a title that helps to convey theme.

- In the well-known opening lines, Dickens uses literary devices such as anaphora, asyndeton, parallelism, and paradox.

- The novel’s characters include both developing and static characters, both types contributing to the development of theme.

- Major themes of the novel are threads of destiny, guilt and retribution, and retribution and redemption.

Exercises

Structure and Theme

Consider the themes conveyed by the three-part structure.

-

Part I Recalled to Life

-

Who is recalled to life? Consider the following characters:

- Dr. Manette

- Charles Darnay

- Sydney Carton

- Jarvis Lorry

- Miss Pross

- How are these characters “recalled to life”?

- What is the purpose of Cruncher and his occupation, “resurrection man”?

-

-

Part II The Golden Thread

- How does Lucie function as a “golden thread,” weaving the events?

- Could Madame DeFarge function as a “golden thread”?

- What are the literal and figurative purposes of Madame DeFarge’s knitting?

-

Part III The Track of a Storm

- What personal “storms” erupt in Part III?

- What public “storms”?

Characters

- Trace the development of Sydney Carton’s character from his dissipated state to his redemption. What forces affect his developing character?

- Compare Lucie, the stereotypical Victorian upper class woman, with Miss Pross, the stereotypical Victorian lower class woman.

- Why doesn’t Madame DeFarge anticipate Carton’s action?

- What explanation does the novel provide for Madame DeFarge’s evil? After learning the explanation, do her actions seem justified?

- In what ways and why is The Vengeance different from Madame DeFarge?

- In what ways do the two cities represent “poetic justice,” with the “good guys” ending up in England and the “bad guys” ending up in France?

- Compare and contrast Dickens’s portrayal of London and Paris with the Romantic poets’ depiction of the pastoral countryside and the industrialized city.

Images

- Identify images of light and dark throughout the novel. What themes do these images support?

- Locate references to footsteps throughout the novel. What is the purpose of these references? Also consider Dr. Manette’s shoemaking; explain how it symbolizes the path he makes for his own and Lucie’s fate.

- List instances of the spilling of wine throughout the novel. How do these incidents function literally in the plot and figuratively in reinforcing theme?

Themes

- How do references to Lucie’s hair connect to the “threads of destiny” motif?

- How and why is Darnay different from his relative St. Evrémondes? How do his decisions and actions contribute to a destiny different from his uncle’s?

- What role does Dr. Manette’s letter play in the theme of guilt and retribution?

-

Almost all the characters in the novel play a role in developing the theme of retribution and redemption. Identify which of the following characters represent retribution and which represent redemption. After compiling this initial list, reconsider each character to determine those who are more complex, who embody elements of both retribution and redemption.

- Darnay

- Carton

- Dr. Manette

- Lorry

- Minor characters: Cruncher, Barsad

-

Identify examples of the doppelganger and describe their function in the novel. Include the following examples:

- London-Paris

- Darnay-Carton

- Lucie-Madame DeFarge and/or Miss Pross-Madame DeFarge

Resources

General Information

- “Charles Dickens.” The Victorian Web. George P. Landow, Brown University.

- David Perdue’s Charles Dickens Page.

- “Dickens in Context.” The British Library. includes videos and images.

- The Dickens Project. University of California.

Biography

- “Charles Dickens (1812–1870).” BBC History.

- “Charles Dickens—Biographical Information.” The Victorian Web. George P. Landow, Brown University.

- “Charles Dickens: The Life of the Author.” Kenneth Benson. The New York Public Library.

A Tale of Two Cities

- “A Tale of Two Cities.” Discovering Dickens—A Community Reading Project. Stanford University.

- “Some Discussions of Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities.” The Victorian Web. George P. Landow, Brown University.

Text

- Dickens, Charles, 1812–1870. A Tale of Two Cities. Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library.

- A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens. Project Gutenberg.

- A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens. A. L. Burt Company, Publishers, New York. 1890. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

Video

- “Charles Dickens Animation.” BBC Home.

- “Virtual Guide for Charles Dickens Birthplace.” Portsmouth Museums and Records.

Audio

- “A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens (1812–1870).” LibriVox.

- “A Tale of Two Cities.” Charles Dickens. Lit2Go. Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida.

Images

- “Charles Dickens.” Great Britons: Treasures from the National Portrait Gallery, London.

7.3 Emily Brontë (1818–1848)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- List major characters, explain their roles in the plot, and analyze their characters within the novel and as they might be interpreted by both Victorian and contemporary audiences.

- Outline the chronology of the novel’s major events, and compare and correlate the chronology with the order in which events are presented in the novel.

- Assess the relationship between character and setting, and provide specific examples.

- Analyze the differences in relationships among the second generation and the third generation that allow the younger characters to resolve the novel’s conflicts.

Biography

The village of Haworth website offers virtual tours of the interior of the Brontë Parsonage Museum.

Text

- Wuthering Heights. Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library.

- Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë. Project Gutenberg.

- Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey. The Haworth Edition. New York and London. Harper & Brothers Publishers. 1900. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

Wuthering Heights (1846)

A novel, according to Holman and Harmon’s standard definition is an “extended fictional prose narrative.” A novel’s components include character, plot, structure, setting, and theme.

An 1846 edition of Poems showing the use of pen names, Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell.

Emily Brontë’s drawing of herself and Anne writing at a table in the Bronté parsonage in Haworth. This sketch is on display in the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth.

As in most novels, in Wuthering Heights character, plot, and structure are tightly interwoven; one element drives the others. Particularly significant in Wuthering Heights is setting, which Brontë uses to reflect character.

- Character: While contemporary audiences tend to read Wuthering Heights with a sympathetic view of Heathcliff and Catherine, Victorian audiences would have agreed that Edgar was the appropriate choice of a husband for Catherine. We may think that couples should follow their hearts, but a Victorian audience, particularly an upper or middle class audience, would have believed that Catherine had a duty to marry her social equal—Edgar. The conflict within Catherine as she feels torn between Heathcliff and Edgar is a focal point of the novel. Her death marks the transition between the two parts of the story. Of course, Wuthering Heights is largely Heathcliff’s story; his desire for revenge drives the plot.

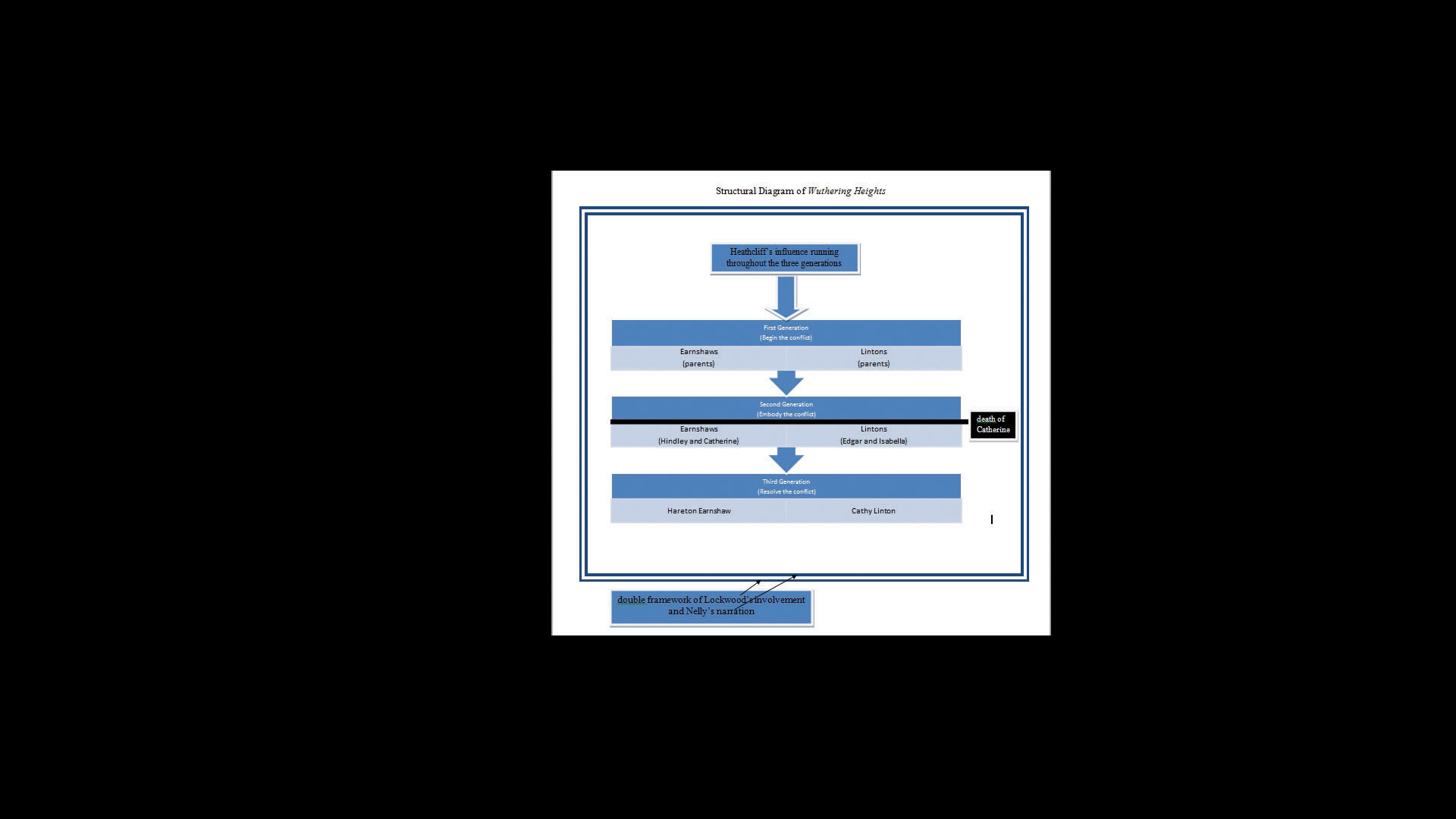

- Plot: The main story is told as a flashbackThe insertion of an event from earlier in the natural chronology that interrupts the narrative., the insertion of an event from earlier in the natural chronology that interrupts the narrative. The story opens with the arrival of Lockwood at Wuthering Heights. After his nightmarish encounter with the apparition of Catherine, Nelly Dean begins to tell Lockwood the story of the Earnshaws and the Lintons. Most of the book, then, is her narration of events that have already happened. The final chapters return to the novel’s present, the time of Lockwood, as the conflicts are resolved.

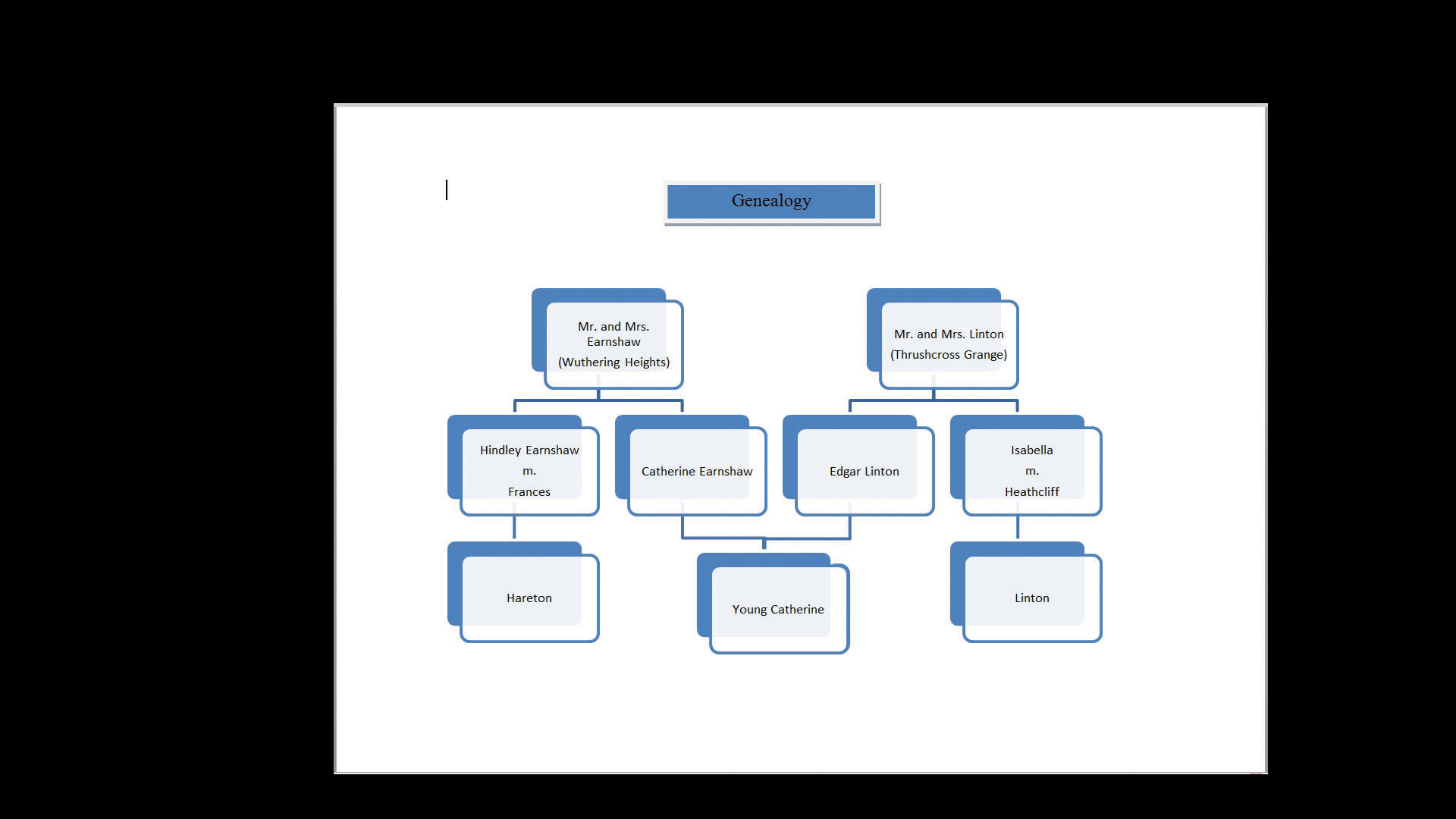

- Structure: The structure of Wuthering Heights is built on the three generations of characters in the story: the older generation (who set in motion the conflicts); their children (who comprise the conflicts of the novel); and the youngest generation (who resolve the conflicts). Through these three layers of characters runs a connecting thread in the character of Heathcliff. Providing a framework for this structure are the narrations of Nelly and Lockwood.

- Setting: The characteristics of the two families, the Earnshaws and the Lintons, are reflected in their homes, Wuthering Heights and Thrushcross Grange. Even the weather is used to mirror the emotions of the characters.

A structural diagram of Wuthering Heights.

Video Clip 3

Emily Brontë and the Yorkshire Moors

(click to see video)View a video mini-lecture about Emily Bronte and the Yorkshire Moors.

Key Takeaways

- Heathcliff, the structurally central character of the novel, is a Byronic hero, generally sympathetic to modern audiences but generally unsympathetic to Victorian audiences.

- Wuthering Heights and Thrushcross Grange reflect the characters who live there, and conflict occurs when Catherine attempts to cross the social boundaries represented by the estates, boundaries well established for Victorian audiences.

- Setting, including the weather, reflects character.

- The third generation resolves the conflicts, in part by overcoming the social restrictions that bound their parents.

Exercises

Catherine

- How does Brontë depict Catherine’s attachment to Heathcliff when they were children? What character traits do Catherine and Heathcliff share that might have drawn them to each other? Identify specific events or specific character traits.

- How does Catherine change after her stay with the Lintons at Thrushcross Grange? How do the changes affect her relationship with Heathcliff?

- After Catherine’s stay with the Lintons, it becomes clear that she has developed a relationship with Edgar Linton. How would you describe that relationship? How does it affect her relationship with Heathcliff? What factors in society or in Catherine herself affect her feelings about each man?

- What reasons does Catherine give in her conversation with Nelly for deciding to marry Edgar? How does Nelly respond to her reasoning? During this conversation, Nelly is aware that Heathcliff is listening to part of the conversation although Catherine is not. How does Nelly’s decision not to tell Catherine affect the events of the novel? Why did Nelly make the decision not to reveal that Heathcliff was there?

- What does Catherine mean when she says, “I am Heathcliff”?

- Catherine is often described as having a dual personality or a split personality. She feels drawn in contradictory directions, torn between Edgar and Heathcliff. In fact, her death is attributed to this duality that she is unable to reconcile. What events bring about the crisis that results in her death?

- When Heathcliff returns after Catherine is married to Edgar, Catherine seems surprised that Nelly, Edgar, and society in general disapprove of her continuing her friendship with Heathcliff. Why would she expect to continue what society sees as an improper relationship? At the end of the novel, Catherine is buried between Edgar and Heathcliff wearing a locket that contains a lock of each man’s hair. How do you characterize Catherine’s relationship with the two men?

Heathcliff

- Emily Brontë’s sister Charlotte Brontë wrote a preface for the 1850 edition of Wuthering Heights in which she stated, “Whether it is right or advisable to create beings like Heathcliff, I do not know: I scarcely think it is.” Heathcliff is a Byronic anti-hero; in Victorian eyes he would be seen as an evil person without redeeming qualities, the opinion Charlotte Brontë expressed. Modern audiences might be more inclined to see Heathcliff as a product of his environment. What childhood events and relationships contribute to the warping of Heathcliff’s personality?

- When Nelly informs Heathcliff that Catherine has died, Heathcliff cries out for Catherine to “haunt” him. What evidence indicates that she does, figuratively or literally?

- When Hindley dies, Heathcliff determines to bring up Hareton himself at Wuthering Heights. He comments to Hareton, “Now, my bonny lad, you are mine! And we’ll see if one tree won’t grow as crooked as another, with the same wind to twist it!” What does Heathcliff mean? What does this comment reveal about Heathcliff’s character?

- What incident when Hareton was small indicates that Heathcliff may have some concern for him?

- Describe Heathcliff’s treatment of his wife Isabella and his son Linton.

- Near the end of the novel, Heathcliff’s desire for revenge seems to burn itself out. What causes this change, and what incidents illustrate his decreasing interest in life?

The Younger Generation

- Describe young Cathy when Lockwood first meets her. Describe her relationship with Hareton and the reasons for it.

- Describe Hareton as he appears when Lockwood first meets him. How has his life been similar to Heathcliff’s? Although he has experienced some of the same difficulties, he has not become hardened, or even evil, like Heathcliff; why? Do internal characteristics or outside influences temper his character?

- Although Linton is a pathetic character, he is not entirely sympathetic. How would you describe him? How would you account for his selfish, petty behavior?

- Describe Cathy and Hareton when Lockwood meets them again at the end of the novel. What has caused the change? How is that change reflected in the physical description of Wuthering Heights?

- How would you compare Cathy and Hareton with Catherine and Heathcliff?

The Settings

- Describe Wuthering Heights as it appears at the beginning of the novel. How is the description different at the end of the novel?

- How does weather function to reveal character? Consider the snowstorm at the beginning of the story, the storm the night Heathcliff leaves, and the weather at the end of the novel.

- How do the settings of the moors and the valley function to reveal character?

- Compare Wuthering Heights and Thrushcross Grange. How do the two estates reflect the characters who live there?

Resources

General Information

- “The Brontës.” The Brontë Parsonage Museum & Brontë Society.

- “Emily Brontë (1818–48).” The Victorian Web. links to biographical and critical information.

- “’Haworth, November 1904’ by Virginia Woolf.” Mary Mark Ockerbloom, ed. A Celebration of Women Writers.

- “Love on the Moors: The Bronte Family.” Sublime Anxiety: The Gothic Family and The Outsider. University of Virginia.

- “Overview of Emily Brontë.” Emily Brontë. Lilia Melani, Brooklyn College, City University of New York.

- “The Romantic Novel, Romanticism, and Wuthering Heights.” Lilia Melani, Brooklyn College, City University of New York.

Biography

- “Emily Jane Brontë.” The Brontë Parsonage Museum & Brontë Society.

- “Emily Jane Brontë: Poet and Novelist (1818–48).” The Victorian Web. Philip V. Allingham, Lakehead University.

Text

- Wuthering Heights. Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library.

- Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë. Project Gutenberg.

- Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey. The Haworth Edition. New York and London. Harper & Brothers Publishers. 1900. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

Audio

- Wuthering Heights. Learn Out Loud.com.

- Wuthering Heights. LibriVox.

Video

- Emily Bronte. Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.

- Emily Bronte and the Yorkshire Moors. Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.

Concordance

- “A Hyper-Concordance to the Works of the Brontë Sisters.” The Victorian Literary Studies Archive. Prof. Mitsu Matsuoka, Nagoya University.

7.4 Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Characterize Sonnets from the Portuguese as a sonnet sequence.

- Analyze and evaluate Barrett Browning’s “The Cry of the Children” as persuasive discourse.

Biography

PowerPoint 7.1.

Follow-along file: PowerPoint title and URL to come.

Texts

- “The Cry of the Children.” Edmund Clarence Stedman, ed. A Victorian Anthology, 1837–1895. Bartleby.com.

- “The Cry of the Children” in The Poetical Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. London: Oxford University Press, 1920. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- “The Cry of the Children” in The Poetical Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Project Gutenberg.

- Sonnets from the Portuguese. London: George Bell and Sons, 1900. Google Books.

- Sonnets from the Portuguese. Project Gutenberg.

- Sonnets from the Portuguese in The Poetical Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. London: Oxford University Press, 1920. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

Sonnets from the Portuguese

Barrett Browning’s sonnets were written to express her feelings for her husband Robert Browning. She never intended that they be published but acquiesced to her husband’s opinion that the poems were too good to keep from the world. Various biographers have attempted to explain the title: “Portuguese” was supposedly a pet name Browning had for his wife. Or the title may have been intended to disguise the biographical nature of the poems by suggesting that they were translated from the Portuguese language.

Sonnets from the Portuguese form a sonnet sequenceA group of sonnets exploring all aspects of a topic., a group of sonnets exploring all aspects of a topic, a form of literature that had reached its height of popularity in the 16th century. Barrett Browning uses the form to trace the growth of a love, at first tentative, then more self-assured as the sequence progresses.

Sonnet 43

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of Being and ideal Grace.

I love thee to the level of everyday’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for Right;

I love thee purely, as they turn from Praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints!—I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life!—and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

Sonnet 43 is one of the world’s best known poems. The first line, “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways,” surely figures in the most often quoted poetic lines.

The poet recounts eight ways in which she loves:

- Her love is as expansive as the space her soul is capable of reaching.

- Her love encompasses everyday moments, by night and day, in contrast to the expansive metaphor of the first “way of loving.”

- Her love is freely given. She compares this gift of love to the way men voluntarily strive for the things they believe in.

- Her love is pure as the men fighting for their beliefs do so from pure motives, not for glory or honor.

- Her love is as intense as the passions she felt in her childhood.

- Her love is as intense as the love she thought she’d lost when she lost her childhood “saints,” perhaps a reference to loved ones she lost through death, or perhaps a reference to disillusionment—learning that people she considered “saints” are not perfect.

- Her love lasts through “smiles” and “tears,” good and bad experiences.

- Her love will last even after death.

“The Cry of the Children”

“Pheu, pheu, ti prosderkesthe m’ ommasin, tekna?”’

Medea

I.

Do ye hear the children weeping, O my brothers,

Ere the sorrow comes with years?

They are leaning their young heads against their mothers.

And that cannot stop their tears.

The young lambs are bleating in the meadows,

The young birds are chirping in the nest,

The young fawns are playing with the shadows,

The young flowers are blowing toward the west—

But the young, young children, O my brothers,

They are weeping bitterly!

They are weeping in the playtime of the others,

In the country of the free.

II.

Do you question the young children in the sorrow

Why their tears are falling so?

The old man may weep for his to-morrow

Which is lost in Long Ago;

The old tree is leafless in the forest,

The old year is ending in the frost,

The old wound, if stricken, is the sorest,

The old hope is hardest to be lost:

But the young, young children, O my brothers,

Do you ask them why they stand

Weeping sore before the bosoms of their mothers,

In our happy Fatherland?

III.

They look up with their pale and sunken faces,

And their looks are sad to see,

For the man’s hoary anguish draws and presses

Down the cheeks of infancy;

“Your old earth,” they say, “is very dreary,

Our young feet,” they say, “are very weak;

Few paces have we taken, yet are weary—

Our grave-rest is very far to seek:

Ask the aged why they weep, and not the children,

For the outside earth is cold,

And we young ones stand without, in our bewildering,

And the graves are for the old.”

IV.

“True,” say the children, “it may happen

That we die before our time:

Little Alice died last year, her grave is shapen

Like a snowball, in the rime.

We looked into the pit prepared to take her:

Was no room for any work in the close clay!

From the sleep wherein she lieth none will wake her,

Crying, ‘Get up, little Alice! it is day.’

If you listen by that grave, in sun and shower,

With your ear down, little Alice never cries;

Could we see her face, be sure we should not know her,

For the smile has time for growing in her eyes:

And merry go her moments, lulled and stilled in

The shroud by the kirk-chime.

It is good when it happens,” say the children,

“That we die before our time.”

V.

Alas, alas, the children! they are seeking

Death in life, as best to have:

They are binding up their hearts away from breaking,

With a cerement from the grave.

Go out, children, from the mine and from the city,

Sing out, children, as the little thrushes do;

Pluck your handfuls of the meadow-cowslips pretty,

Laugh aloud, to feel your fingers let them through!

But they answer, “Are your cowslips of the meadows

Like our weeds anear the mine?

Leave us quiet in the dark of the coal-shadows,

From your pleasures fair and fine!

VI.

“For oh,” say the children, “we are weary,

And we cannot run or leap;

If we cared for any meadows, it were merely

To drop down in them and sleep.

Our knees tremble sorely in the stooping,

We fall upon our faces, trying to go;

And, underneath our heavy eyelids drooping,

The reddest flower would look as pale as snow.

For, all day, we drag our burden tiring

Through the coal-dark, underground;

Or, all day, we drive the wheels of iron

In the factories, round and round.

VII.

“For all day the wheels are droning, turning;

Their wind comes in our faces,

Till our hearts turn, our heads with pulses burning,

And the walls turn in their places:

Turns the sky in the high window, blank and reeling,

Turns the long light that drops adown the wall,

Turn the black flies that crawl along the ceiling:

All are turning, all the day, and we with all.

And all day the iron wheels are droning,

And sometimes we could pray,

‘O ye wheels’ (breaking out in a mad moaning),

‘Stop! be silent for to-day!’”

VIII.

Ay, be silent! Let them hear each other breathing

For a moment, mouth to mouth!

Let them touch each other’s hands, in a fresh wreathing

Of their tender human youth!

Let them feel that this cold metallic motion

Is not all the life God fashions or reveals:

Let them prove their living souls against the notion

That they live in you, or under you, O wheels!

Still, all day, the iron wheels go onward,

Grinding life down from its mark;

And the children’s souls, which God is calling sunward,

Spin on blindly in the dark.

IX.

Now tell the poor young children, O my brothers,

To look up to Him and pray;

So the blessed One who blesseth all the others,

Will bless them another day.

They answer, “Who is God that He should hear us,

While the rushing of the iron wheels is stirred?

When we sob aloud, the human creatures near us

Pass by, hearing not, or answer not a word.

And we hear not (for the wheels in their resounding)

Strangers speaking at the door:

Is it likely God, with angels singing round Him,

Hears our weeping any more?

X.

“Two words, indeed, of praying we remember,

And at midnight’s hour of harm,

‘Our Father,’ looking upward in the chamber,

We say softly for a charm.[1]

We know no other words except ‘Our Father,’

And we think that, in some pause of angels’ song,

God may pluck them with the silence sweet to gather,

And hold both within His right hand which is strong.

‘Our Father!’ If He heard us, He would surely

(For they call Him good and mild)

Answer, smiling down the steep world very purely,

‘Come and rest with me, my child.’

XI.

“But, no!” say the children, weeping faster,

“He is speechless as a stone:

And they tell us, of His image is the master

Who commands us to work on.

Go to!” say the children,—“up in Heaven,

Dark, wheel-like, turning clouds are all we find.

Do not mock us; grief has made us unbelieving:

We look up for God, but tears have made us blind.”

Do you hear the children weeping and disproving,

O my brothers, what ye preach?

For God’s possible is taught by His world’s loving,

And the children doubt of each.

XII.

And well may the children weep before you!

They are weary ere they run;

They have never seen the sunshine, nor the glory

Which is brighter than the sun.

They know the grief of man, without its wisdom;

They sink in man’s despair, without its calm;

Are slaves, without the liberty in Christdom,

Are martyrs, by the pang without the palm:

Are worn as if with age, yet unretrievingly

The harvest of its memories cannot reap,—

Are orphans of the earthly love and heavenly.

Let them weep! let them weep!

XIII.

They look up with their pale and sunken faces,

And their look is dread to see,

For they mind you of their angels in high places,

With eyes turned on Deity.

“How long,” they say, “how long, O cruel nation,

Will you stand, to move the world, on a child’s heart,—

Stifle down with a mailed heel its palpitation,

And tread onward to your throne amid the mart?

Our blood splashes upward, O gold-heaper,

And your purple shows your path!

But the child’s sob in the silence curses deeper

Than the strong man in his wrath.”

The epigraph to Barrett Browning’s poem from Euripides’s Greek tragedy Medea may be translated, “Woe, woe, why do you look at me with your eyes, children?” Stanzas 1 and 2 begin with questions for Barrett Browning’s readers, directing their attention to the children’s tears. The suffering and sorrow felt by the children is to be expected only in a much older person, one who has lived long enough to experience life’s hardships.

Stanza 4 relates the children’s reactions to the death of Alice, one of the children. The children peer into her grave, noting that there is no room for her to do the work she’s been used to. Alice will never again hear someone calling her from her bed at dawn to resume her work, and the children do not hear her crying from her grave. Based on these observations, in their childish reasoning, they conclude that death is preferable to life.

Stanzas 5 and following address the children’s relationship to nature and to God while always pleading with the reader to recognize the children’s plight. The last stanza addresses the reader directly with a condemnation of a society that allows this situation to exist.

Key Takeaways

- “Sonnets from the Portuguese” is a sonnet sequence.

- “The Cry of the Children” is persuasive discourse.

- “The Cry of the Children” drew on published government documents inquiring into child labor abuses.

Exercises

- “The Cry of the Children” falls into the category of persuasive discourse. Who is Barrett Browning attempting to persuade? Of what is she attempting to persuade her audience? Persuasive discourse uses logical (logos) and emotional appeal (pathos); what examples of each type of appeal do you find in this poem?

-

Read some of the following documents from the Victorian era about child labor:

- “Testimony Gathered by Ashley’s Mines Commission.” The Victorian Web. Laura Del Col, West Virginia University.

- “Early Factory Legislation.” Reforming Society in the 19th Century. Living Heritage. www.parliament.uk.

- “The 1833 Factory Act.” Reforming Society in the 19th Century. Living Heritage. www.parliament.uk.

- “News on Mine Accidents.” Victorian Britain: An Industrial Nation. National Archives.

- “Child Miners.” Victorian Britain: An Industrial Nation. National Archives.

Which do you find more persuasive, Barrett Browning’s poem or the documents? Which do you think would have been more effective in convincing a Victorian audience to take action?

- Barrett Browning uses descriptions of nature although there is no hint of Romantic mysticism. What is the purpose of the natural descriptions in “The Cry of the Children”?

- Barrett Browning also uses frequent references to wheels. What is the literal and metaphorical meaning of the wheels? An apostrophe is an address to an inanimate object or an abstract quality. In stanzas 7 and 8, Barrett Browning addresses the wheels; what is the purpose of this apostrophe?

- Compare Barrett Browning’s description of the children and their lives with Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience, particularly in the “Holy Thursday” and “Chimney Sweeper” poems. Compare the children’s attitude toward religion in both authors’ works. Compare the line “if all do their duty we need not fear harm” from the Innocence “The Chimney Sweeper” with the last stanza of “The Cry of the Children.”

Resources

Biography

- The Browning Letters. Baylor University and Wellesley College.

- “Elizabeth Barrett Browning.” The Browning Society.

- “Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861).” The Brownings. Armstrong Browning Library. Baylor University.

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning—Biographical Materials. The Victorian Web. George P. Landow, Brown University.

- “Guidi House—Casa Guidi.” The Museums of Florence.

Texts

- “The Cry of the Children” in The Poetical Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. London: Oxford University Press, 1920. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- “The Cry of the Children” in The Poetical Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Project Gutenberg.

- Sonnets from the Portuguese in The Poetical Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. London: Oxford University Press, 1920. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- Sonnets from the Portuguese. Project Gutenberg.

Audio

- “The Cry of the Children.” LibriVox.

- Sonnets from the Portuguese. LibriVox.

- Sonnets from the Portuguese. Project Gutenberg.

Video

- “Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

7.5 Robert Browning (1812–1889)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Define dramatic monologue and apply the definition to appropriate poems by Robert Browning.

- Define lyric and apply the definition to appropriate poems by Robert Browning.

- Describe the speakers in “Porphyria’s Lover,” “My Last Duchess,” and “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed’s Church.” Consider their words, implied actions, tone, and inferences drawn from their speeches.

Biography

Robert Browning was born in 1812, the son of a prosperous bank clerk and a nonconformist, musical mother. His father collected a voluminous library, and, disliking school, Browning grew up largely self educated in his father’s library, both he and his sister Sarianna immersed in a household filled with music, art, and literature. His early poems, such as Pauline and Paracelsus, attracted little attention. Encouraged by an actor friend, William Macready, Browning attempted to write several plays, none of which was particularly successful on stage. His next published long poem Sordello was ravaged by critics and popular writers of the time, such as Tennyson and Thomas Carlyle, and earned Browning a reputation for “obscurity” which persists to the present.

Browning’s attempts at writing plays did lead him to develop a form for which he is most well-known, the dramatic monologue, a poem spoken by a single speaker to a recognizable but silent audience at a critical moment in the speaker’s life. Although he did not invent the dramatic monologue form, he perfected it and used it so well that it has come to be closely associated with Browning.

The negative critical reception much of Browning’s early work received may account for the exceptional notice he took of Elizabeth Barrett’s mention of him in her poem “Lady Geraldine’s Courtship”:

Or from Browning some “Pomegranate,” which, if cut deep down the middle, shows a heart within blood-tinctured of a veined humanity.

Feeling as if he’d found someone who understood his poetry, Browning began corresponding with Barrett and, through mutual friend John Kenyon, one of London’s literati, arranged to meet her. After their marriage and move to Florence, Italy, the most productive period of Browning’s life began with the publication of Men and Women in 1855.

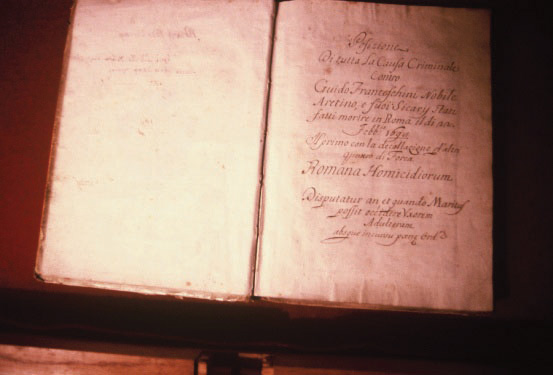

Browning’s magnum opus The Ring and the Book is a verse novel consisting of twelve books, ten books presenting ten dramatic monologues recounting a sensational murder trial that took place in Italy in 1698. In the introductory Book I, Browning describes walking through a street market in Florence and purchasing what he called The Old Yellow Book, a compilation of documents pertaining to the trial from which he drew the story conveyed in The Ring and the Book. This is the “Book” of the title. The “Ring” of the title may refer to an actual ring or to the ring of stories which attempt to arrive at the truth of the murder case. The verse novel is an experiment in dialectical writing, a story told through nine different filters (one character, the murderer Guido Franceschini, speaks two books), nine characters with their own preconceptions and circumstances which color their versions of the truth. The speakers of the monologues reveal as much about themselves as they do about the murder—which is the main purpose of a dramatic monologue: to reveal the character of the speaker.

The Old Yellow Book on display in the Browning Room at Balliol College, Oxford.

By the time of his death in 1889, Browning had become a major figure in England’s literary scene. He was buried in Westminster Abbey’s Poets Corner although he had expressed to his son his desire to be buried next to his wife Elizabeth Barrett Browning in Florence, Italy.

Texts

- “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed’s Church Rome, 15—.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed’s Church, 15—.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

- “Home Thoughts from Abroad.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “My Last Duchess.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “My Last Duchess.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

- “Porphyria’s Lover.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “Porphyria’s Lover.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

- “Prospice.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

The Dramatic Monologue

From John Donne in the 17th century to Robert Burns in the late 18th century, poets wrote dramatic monologues. Browning, however, is most often associated with the form, and his dramatic monologues are considered his best poems.

Although the dramas that Browning wrote early in his career were not successful as theater productions, they reveal a gift for creating fictional characters and presenting them through their speeches. While this made “talky,” uninteresting stage presentations, it created dynamic poetry.

A dramatic monologue has the following four characteristics:

- a fictional speaker

- a speech made at a dramatic moment in the speaker’s life

- a silent but identifiable listener

- a revelation of the speaker’s character

Think of a dramatic monologue as a scene in a play, but a scene in which only one of the characters on stage speaks. The “I” of a dramatic monologue is not the poet; the poet makes up a character who delivers the speech. It is this fictional character whose life and thoughts we hear about.

The speech that is the dramatic monologue is given at a dramatic moment in the speaker’s life; some significant event has or is about to occur.

The existence of a silent but identifiable listener means that the speaker is not the only character present in this scene. We can tell from the speaker’s comments that another person (or persons) is present, but the poem contains only the words of the speaker.

A dramatic monologue reveals the character of the speaker. By hearing what s/he says, we know what kind of person s/he is.

Robert Browning was interested in psychology; his dramatic monologues give us insight into a variety of people—some good, some evil. In “Porphyria’s Lover,” for example, Browning takes his audience into the mind of a psychotic man. We wonder how someone could commit such a violent act, and Browning’s poem attempts to let us see how this criminally insane mind works.

Porphyria’s Lover

The rain set early in tonight,

The sullen wind was soon awake,

It tore the elm-tops down for spite,

And did its worst to vex the lake:

I listened with heart fit to break.

When glided in Porphyria; straight

She shut the cold out and the storm,

And kneeled and made the cheerless grate

Blaze up, and all the cottage warm;

Which done, she rose, and from her form

Withdrew the dripping cloak and shawl,

And laid her soiled gloves by, untied

Her hat and let the damp hair fall,

And, last, she sat down by my side

And called me. When no voice replied,

She put my arm about her waist,

And made her smooth white shoulder bare,

And all her yellow hair displaced,

And, stooping, made my cheek lie there,

And spread, o’er all, her yellow hair,

Murmuring how she loved me—she

Too weak, for all her heart’s endeavor,

To set its struggling passion free

From pride, and vainer ties dissever,

And give herself to me forever.

But passion sometimes would prevail,

Nor could tonight’s gay feast restrain

A sudden thought of one so pale

For love of her, and all in vain:

So, she was come through wind and rain.

Be sure I looked up at her eyes

Happy and proud; at last l knew

Porphyria worshiped me: surprise

Made my heart swell, and still it grew

While I debated what to do.

That moment she was mine, mine, fair,

Perfectly pure and good: I found

A thing to do, and all her hair

In one long yellow string l wound

Three times her little throat around,

And strangled her. No pain felt she;

I am quite sure she felt no pain.

As a shut bud that holds a bee,

I warily oped her lids: again

Laughed the blue eyes without a stain.

And l untightened next the tress

About her neck; her cheek once more

Blushed bright beneath my burning kiss:

I propped her head up as before,

Only, this time my shoulder bore

Her head, which droops upon it still:

The smiling rosy little head,

So glad it has its utmost will,

That all it scorned at once is fled,

And I, its love, am gained instead!

Porphyria’s love: she guessed not how

Her darling one wish would be heard.

And thus we sit together now,

And all night long we have not stirred,

And yet God has not said a word!

“My Last Duchess” is based on an historical incident involving the Duke of Ferrara, Italy during the Renaissance.

My Last Duchess

Ferrara

That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall,

Looking as if she were alive. I call

That piece a wonder, now: Frà Pandolf’s hands

Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

Will’t please you sit and look at her? I said

“Frà Pandolf” by design: for never read

Strangers like you that pictured countenance,

The depth and passion of its earnest glance,

But to myself they turned (since none puts by

The curtain I have drawn for you, but I)

And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst,

How such a glance came there; so, not the first

Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, ‘twas not

Her husband’s presence only, called that spot

Of joy into the Duchess’ cheek: perhaps

Frà Pandolf chanced to say “Her mantle laps

Over my lady’s wrist too much,” or “Paint

Must never hope to reproduce the faint

Half-flush that dies along her throat:” such stuff

Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough

For calling up that spot of joy. She had

A heart—how shall I say?—too soon made glad,

Too easily impressed; she liked whate’er

She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

Sir, ‘twas all one! My favour at her breast,

The dropping of the daylight in the West,

The bough of cherries some officious fool

Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule

She rode with round the terrace—all and each

Would draw from her alike the approving speech,

Or blush, at least. She thanked men,—good! but thanked

Somehow—I know not how—as if she ranked

My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name

With anybody’s gift. Who’d stoop to blame

This sort of trifling? Even had you skill

In speech—(which I have not)—to make your will

Quite clear to such an one, and say, “Just this

Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss,

Or there exceed the mark”—and if she let

Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set

Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse,

—E’en then would be some stooping: and I choose

Never to stoop. Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt,

Whene’er I passed her; but who passed without

Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands;

Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands

As if alive. Will’t please you rise? We’ll meet