This is “The Romantic Period”, chapter 6 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 6 The Romantic Period

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

6.1 The Romantic Period (1798–1832)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Trace the political and philosophical roots of Romanticism.

- Compare and contrast neoclassicism and Romanticism.

- List and define characteristics of Romanticism.

- Explain the significance of Wordsworth’s and Coleridge’s 1798 Lyrical Ballads, and outline the major tenets of Wordsworth’s 1802 Preface to Lyrical Ballads.

- List, define, and give examples of typical forms of Romantic literature.

The Roots of Romanticism

Tintern Abbey and the River Wye in Tintern, Wales.

Often the term Romantic literature, particularly poetry, evokes the connotation of nature poetry. Although nature is an important component in much Romantic literature, Romanticism is much more than recording the beauties of the natural world. And Romanticism is certainly not what modern readers usually think of when we hear the words romance and romantic; Romanticism does not refer to romantic love.

Romanticism grew from a profound change in the way people in the Western world perceived their place and purpose in life. Events such as the American Revolution in 1776, the French Revolution in 1789, and the Industrial Revolution restructured society and the way individuals viewed themselves and their relationship to each other and to the social order.

Democracy

In the late 18th and early 19th century, concepts such as the Great Chain of Being, which had long represented the way humans thought of themselves and their roles in society, crumbled in the wake of new ideas about democracy. Rather than placing themselves above or below other individuals in a hierarchy, people began to believe that all men are created equal. Although it took more time to be accepted, the idea that women and people of color are also created equal germinated in the fertile environment of democratic ideals.

Nature and Spirit

European philosophers such as Rousseau and Spinoza maintain that innocence and the potential for human goodness are found in nature; human institutions, such as governments, produce pride, greed, and inequality. Thus nature, and people close to nature, becomes the ideal for Romantic writers.

Nature takes on additional significance with the ideas of philosophers such as Schelling who posits an identity of mind and nature: “Nature is visible spirit.…” For poets such as Wordsworth and Coleridge, nature is a source of divine revelation, a visible veil through which God may be discerned. For others such as Shelley, nature is the means to tapping into the collective power of the human mind, what American writer Ralph Waldo Emerson refers to as the Over-Soul. Nature is the source of human innocence and goodness because nature is a manifestation of the Divine.

For Romantic writers, then, the source of poetry is not a conscious crafting of lines of a certain number of syllables in a certain metrical pattern and rhyme scheme, like the 18th-century heroic couplet. Instead, the source of literature is the inspiration that comes from connecting, through nature, with the divine or the transcendental properties of the human mind. Romantic writers use the term Imagination to refer to this connection. The power of God to create nature is parallel to the poet’s power to create through the Imagination. In his A Defence of Poetry, Percy Bysshe Shelley states that the Imagination “strips the veil of familiarity from the world, and lays bare the naked and sleeping beauty, which is the spirit of its forms.” In his “Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey,” Wordsworth writes of “A motion and a spirit, that impels / All thinking things…” that he finds in nature. In his “The Eolian Harp,” Coleridge pictures all of nature, including humans, as harps creating music when touched by the breeze of Imagination, the “One life” that is “in us and abroad.”

Sturm und Drang

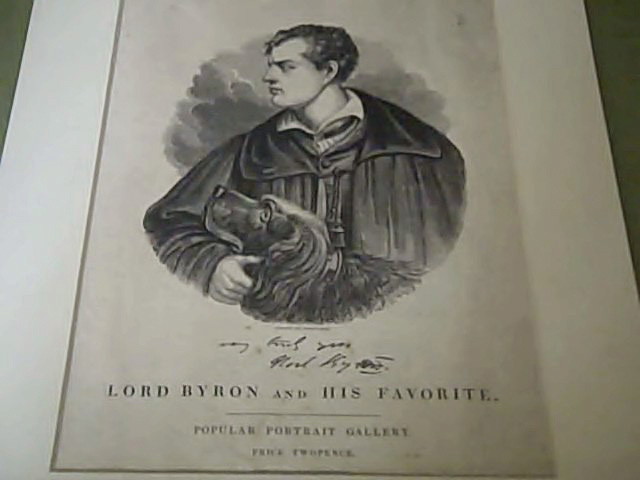

One facet of Romanticism also recognizes the dark side of the human mind. Originating in Germany, the Sturm und Drang (usually translated “storm and stress”) movement pictures an anti-hero, a character dark in appearance, mood, and thought, in rebellion against the restrictions of society. Ann Radcliffe and others wrote Gothic novelsNovels that typically feature picturesque yet haunted medieval castles and ruins, supernatural elements, death, madness, and terror. that typically feature picturesque yet haunted medieval castles and ruins, supernatural elements, death, madness, and terror. Gothic elements appear in many Romantic works: Heathcliff and the ghost of Catherine in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, the mad wife in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey delightfully parodies the Gothic novel. In poetry, Byron’s narrative poems feature dark, brooding anti-heroes called Byronic heroes, a role Byron played himself in his personal life. The Tate Britain provides an online tour through a previous exhibit of paintings that illustrate Romantic Gothic art.

Romanticism and Neoclassicism

Romanticism is a reaction against many facets of Neoclassicism. The following chart lists contrasting views of Neoclassicism and Romanticism.

| Neoclassicism | Romanticism |

|---|---|

| use and imitation of literary traditions from ancient Greece and Rome | use and imitation of literary traditions from the Middle Ages (including the medieval romance) |

| beauty in structure and order | beauty in organic, natural forms |

| art from applying order to nature | art from inspiration |

| heroic couplets | lyric poetry |

| focus on external people and events | focus on self-expression of the artist |

| Great Chain of Being | democracy |

| reason | mysticism |

| Reason leads to spiritual revelation | Nature leads to spiritual revelation |

| urban (glorifies civilization and technological progress) | rural (sees the evils of civilization and technological progress) |

| values wit and sophistication | values primitive, simple people |

| Human nature needs artificial restraints of society | Restraints of society result in tyranny and oppression |

| the head | the heart |

Characteristics of Romantic Literature

- medievalism—Rather than looking for forms and subject matter from classical literature, Romantic-era writers prefer nostalgic views of the Middle Ages as a simple, less complicated time not troubled by the complexities and divisive issues of industrialization and urbanization. Often a Romantic medieval vision is not realistic, ignoring the violence and harshness of the Middle Ages with its religious persecution, political wars, poverty among the lower classes in favor of a fairy tale view of knights in shining armor rescuing beautiful damsels in distress. Or, from another perspective, the castles and mysterious aura of the so-called Dark Ages provide an ideal setting for Gothic literature.

- mysticismThe belief that the physical world of nature is a revelation of a spiritual or transcendental presence in the universe.—Romantic mysticism is the belief that the physical world of nature is a revelation of a spiritual or transcendental presence in the universe. Mysticism is not pantheism (worshipping nature). Romantic writers would worship not the tree, but the spiritual, sublime element manifested by the tree. Romantic literature, particularly poetry, is often characterized as nature poetry; mysticism explains the evident love of nature. Romantic writers love nature not only for its beauty but primarily because it is an expression of spirituality and the Imagination.

- sensibilityThe emotional enthusiasm that was a reaction, often an exaggerated reaction, to the reason and logic prized in neoclassicism.—When Jane Austen titled her novel Sense and Sensibility, she set up the dichotomy between rationalism and the emotional enthusiasm that was a reaction, often an exaggerated reaction, to the reason and logic prized in neoclassicism. In his Preface to Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth defined poetry as the “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings.” The overwhelming emotional reaction to nature seen in Wordsworth’s poetry, the emotional sensitivity to other individuals and their circumstances, particularly those from the lower socio-economic classes, and the supernatural evocation of terror in Gothic literature all are expressions of sensibility.

- primitivism and individualismInterest in the person who does not have the artificial manners of high society, the cultivated façade of the aristocracy.—Arising from two sources, philosophical theories that posit innocence is found in nature and the ideals of democracy, Romanticism values the primitive individual, the person who does not have the artificial manners of high society, the cultivated façade of the aristocracy. Individuals who are closer to nature are better able to recognize and exemplify goodness and spiritual discernment. Wordsworth espouses the common man and incidents from ordinary life as the appropriate subject for poetry. Romanticism places the individual in the center of life and experience.

Lyrical Ballads

Lyrical BalladsA collection of poems written and jointly published by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1798. is a collection of poems written and jointly published by William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1798. The volume is of such importance that its 1798 publication date is often considered the beginning of the Romantic Period. The poetry in Lyrical Ballads marks a distinct change in both subject matter and style from the poetry of the 18th century.

William Wordsworth’s Preface to Lyrical Ballads

In the 1802 edition of Lyrical Ballads Wordsworth includes a PrefaceAn introductory explanation., an introductory explanation, to Lyrical Ballads to explain his theory of how poetry should be written.

The following points from the Preface delineate the characteristics that make these poems markedly different from poetry of the preceding century:

-

The language of poetry should be real language spoken by common people.

During the 18th century, many poets used what Wordsworth called “poetic diction,” flowery or ornate words for ordinary things such as feathery flock instead of birds or finny tribe instead of fish. Wordsworth protests that people don’t use such expressions; therefore poetry shouldn’t either. Notice also that much of Wordsworth’s poetry rejects the uniform stanzas and line lengths that were popular in the 18th century. Much of his poetry is free in form—lines and stanzas of varying lengths in the same poem, more like the “selection of language really used by men.”

-

The subject of poetry should be events from the real lives of common people.

Wordsworth believes that common, ordinary situations are worthy topics for poems, events such as farmers plowing their fields. He further believes that through the Imagination he could make his audience more aware of the significance of common scenes that they might otherwise take for granted.

- “All good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” and “takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.” Thus Wordsworth identifies sensibility rather than reason as the source of poetry.

- A poet is a “man speaking to men” but an individual who is extraordinarily perceptive. Wordsworth believes that the power of the Imagination enables poets to perceive the spiritual dimension found in the ordinary, in, as Coleridge says, all of animate nature. Sensibility allows the poet to understand and to convey the inner being of man and nature.

Forms of Literature

-

Novel

A novelAs famously defined in the Holman/Harmon Handbook to Literature, an “extended fictional prose narrative.”, as famously defined in the Holman/Harmon Handbook to Literature, is an “extended fictional prose narrative.” The novel flourished in the Romantic Period, encompassing novels previously listed by Anne Brontë, Charlotte Brontë, Emily Brontë, Mary Shelley, and Ann Radcliffe; Sir Walter Scott‘s historical novels, known as the Waverly Novels, set in medieval times and glorifying Scottish nationalism; and Jane Austen’s novels of manners, portraying the genteel country life of the Regency era.

-

Lyric Poetry

A lyricA brief poem, expressing emotion, imagination, and meditative thought, usually stanzaic in form. is a brief poem, expressing emotion, imagination, and meditative thought, usually stanzaic in form.

-

Romantic Ode

As used in the Romantic Period, the odeA lyric poem longer than usual lyrics, often on a more serious topic, usually meditative and philosophic in tone and subject. is a lyric poem longer than usual lyrics, often on a more serious topic, usually meditative and philosophic in tone and subject.

-

Ballad

A balladA narrative poem or song, usually simple and regular in rhythm and rhyme. The typical ballad stanza is 4 lines rhyming abab. is a narrative poem or song. Ballads originated as songs that were part of an oral culture, usually simple and regular in rhythm and rhyme. The typical ballad stanza is 4 lines rhyming abab. Because of their simplicity and their role as part of folk culture, ballads were popular with many Romantic writers.

Key Takeaways

- Romanticism grew from a political and philosophical milieu which promoted democracy, equated nature and spirit, and valued sensibility over reason.

- Lyrical Ballads, published in 1798, is often considered the beginning of the Romantic period because Wordsworth’s and Coleridge’s poetry marks a distinct change in form and subject matter from neoclassical poetry.

- In his Preface to the 1802 edition of Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth delineates the principles that define Romanticism and distinguish Romantic poetry from neoclassical poetry.

- Important forms of Romantic literature are the novel, lyric poetry, odes, and ballads.

Resources

General Information

- British Women Romantic Poets 1789–1832. University of California, Davis. an electronic collection of texts.

- “Nineteenth-Century Literature.” Literary History.com. Jan Pridmore.

- Romantic Circles. Neil Fraistat and Steven E. Jones, editors. University of Maryland.

- “Romanticism.” I Hear America Singing. Profiles: Artists, Movements, Ideas. Thomas Hampson. PBS.

- “Romanticism.” Lilia Melani. English Department. Brooklyn College. City University of New York.

- Women Poets of the Romantic Period 1770–1839. Special Collections. University Libraries. University of Colorado at Boulder.

French Revolution

- “The French Revolution.” The National Archives.

Industrial Revolution

- “1770s.” English Language and Literature Timeline. British Library.

- “The British Industrial Revolution.” Pamela E. Mack. Clemson University.

- “Child Labor.” The Victorian Web. David Cody. Hartwick College.

- “The Life of the Industrial Worker in Nineteenth-Century England.” The Victorian Web. Laura Del Col. West Virginia University.

Gothic Novels

- “Ann Radcliffe: An Evaluation.” The Victorian Web. David Cody. Hartwick College.

- “Gothic Nightmares: Fuseli, Blake, and the Romantic Imagination.” Tate Britain. images of paintings in the Tate Britain museum displayed for an exhibit on Romantic Gothic art.

- Mary Shelley’s Hand-Written Draft of Frankenstein. Shelley’s Ghost: Reshaping the Image of a Literary Family. Bodleian Libraries. Oxford University Exhibit in partnership with the New York Public Library. virtual book with turnable pages and slideshow.

- “Sublime Anxiety: The Gothic Family and The Outsider.” University of Virginia Library.

Lyrical Ballads

- “Lyrical Ballads.” Dove Cottage and the Wordsworth Museum. Wordsworth Trust.

Forms of Literature

- “Lyric.” Literary Terms and Definitions. Dr. L. Kip Wheeler. Carson-Newman College.

- “Lyric.” The UVic Writer’s Guide. The Department of English. University of Victoria.

- “The Meditative Romantic Ode.” Lilia Melani. English Department. Brooklyn College. City University of New York.

- “Novel.” The UVic Writer’s Guide. The Department of English. University of Victoria.

- “Ode.” Literary Terms and Definitions. Dr. L. Kip Wheeler. Carson-Newman College.

- “Ode.” The UVic Writer’s Guide. The Department of English. University of Victoria.

6.2 Charlotte Turner Smith (1749–1806)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify characteristics of Romanticism in Charlotte Turner Smith’s work.

- Describe Smith’s work as topographical poetry.

Biography

Portrait of Charlotte Turner Smith (1749–1806, frontispiece to an 1827 publication of her Elegiac Sonnets).

Early in her childhood, Charlotte Turner Smith lived in the Sussex downs that figure prominently in her writing. Years after the death of her mother, Smith’s father remarried, promising his new wife that the teenaged Charlotte would not remain in the household. Her father arranged her marriage to a man who proved to be irresponsible, promiscuous, and abusive. While in debtor’s prison with her husband and children, Smith earned enough money from her writing to obtain their release. After leaving her husband, she turned to writing in an attempt to support herself and their children.

Many of the hardships Smith faced in life—the death of her mother, her step-mother’s dislike of her, the death of several of her children, her husband’s abuse—found their way into her novels, poetry, and plays.

Video Clip 1

Charlotte Turner Smith

(click to see video)View a video mini-lecture on Charlotte Turner Smith.

Romanticism

Now recognized as the first woman Romantic writer, perhaps even the first Romantic writer, Charlotte Smith’s work was recognized by and an influence on Romantic poets such as Southey, Wordsworth, and Austen.

Her attention to nature and nature’s association with the supernatural is one of the characteristics that her work shares with other Romantic writers.

Smith is also noted for her use of the sonnet and for initiating a new interest in the sonnet among later Romantic writers such as Wordsworth and Keats. The sonnet form, which had flourished during the Elizabethan Age, was little used during the Age of Enlightenment. Sonnet sequences such as Sidney’s Astrophil and Stella emphasize the emotional ups and downs of a love affair. During the Age of Reason, such blatant sentimentalism was abandoned in favor of reason and rational thought, but with Romanticism came a new interest in literature of sensibility.

Texts

- “Beachy Head with Other Poems.” British Women Romantic Poets, 1789–1832. An Electronic Collection of Texts from the University of California at Davis. Ophilia Yim.

- “Beachy Head: With Other Poems.” Google Books.

- “Charlotte Turner Smith.” The Works of Charlotte Smith—An Electronic Edition. Stephen C. Behrendt. Electronic Text Center, UNL Libraries. University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

- “Elegiac Sonnets.” British Women Romantic Poets, 1789–1832. An Electronic Collection of Texts from the University of California at Davis. Charlotte Payne.

- “Elegiac Sonnets: by Charlotte Smith With Additional Sonnets and Other Poems.” Google Books.

“Sonnet V. To the South Downs”

Ah, hills belov’d! where once, an happy child,

Your beechen shades, “your turf, your flowers among,”

I wove your blue-bells into garlands wild,

And woke your echoes with my artless song.

Ah, hills belov’d! your turf, your flowers remain;

But can they peace to this sad breast restore,

For one poor moment soothe the sense of pain,

And teach a breaking heart to throb no more?

And you, Aruna! in the vale below,

As to the sea your limpid waves you bear,

Can you one kind Lethean cup bestow,

To drink a long oblivion to my care?

Ah, no!—when all, e’en hope’s last ray is gone,

There’s no oblivion—but in death alone!

Like many of Smith’s sonnets, “Sonnet V. To the South Downs” begins with a description of nature intricately tied to memories of her childhood, a pattern later found in much of William Wordsworth’s poetry. The poem’s content soon turns from natural description and the joy of childhood it elicits to the current sense of the speaker’s pain. Lines 6–8 and lines 11 and 12 ask questions which serve as transition to the topic of the speaker’s heartbreak, asking if even the current beauty and the remembrance of past joy can mitigate the speaker’s emotional suffering in the present or the future. The couplet provides the answer: only death can provide the oblivion that will ease the speaker’s pain.

Smith’s volume of sonnets was first published in 1784. In the preface to the first edition, Smith notes that in these poems she records “melancholy moments” by “expressing in verse the sensations those moments brought,” an explanation echoed in Wordsworth’s “emotion recollected in tranquility.”

“Sonnet XLIV. Written in the Church-yard at Middleton, in Sussex.”

Press’d by the moon, mute arbitress of tides,

While the loud equinox its power combines,

The sea no more its swelling surge confines,

But o’er the shrinking land sublimely rides.

The wild blast, rising from the western cave,

Drives the huge billows from their heaving bed;

Tears from their grassy tombs the village dead,

And breaks the silent sabbath of the grave!

With shells and sea-weed mingled, on the shore,

Lo! their bones whiten in the frequent wave;

But vain to them the winds and waters rave;

They hear the warring elements no more:

While I am doom’d-by life’s long storm opprest,

To gaze with envy on their gloomy rest.

All along the southern coast of England, the chalk cliffs continuously erode into the sea. Famous for its South Down walks, the cliff area prominently displays frequent signs warning walkers not to approach the edges. Cliffs often collapse onto the beach far below, taking with them any objects or persons standing on the crumbling ground.

In the small village of Middleton-on-Sea, a church stood near the edge of the cliffs until centuries of erosion caused most of the building to tumble into the sea. As is common in English parish churches, the village graveyard surrounded the church building, allowing the dead to be buried in hallowed ground. During Smith’s lifetime, an unusually high tide swept away part of the ruins of the church as well as land containing graves. Exposed bones were found on the beaches afterwards.

In Sonnet 44, the speaker again describes the physical scene, the focus on the bones left exposed on the shore by the destructive tide. As frequently occurs in these sonnets, the final couplet turns to the speaker’s emotional state.

“Beachy Head”

The last poem written by Charlotte Smith, published posthumously, “Beachy Head” exemplifies many of the characteristics that have come to define Romantic poetry.

Perhaps most obvious is Smith’s focus on the natural world. However, as is typical of Romanticism, nature is valued not just for its beauty but because of mysticism: the sense of a divine presence in nature. Note words with religious connotations in the poem.

The speaker’s references to the hind (the rustic country-dweller) who makes an honest living and to the shepherd who is involved in smuggling both typify primitivism, the interest in the lower social classes, people who live close to nature.

Also, the poem reveals sensibility, the valuing of human emotion over reason.

At the same time, the poem exhibits traits of poetry from the Enlightenment. Note the personification of attributes such as Hope, Fancy, Luxury, and Memory.

Key Takeaways

- Charlotte Turner Smith is considered the first woman Romantic writer, perhaps even the first Romantic writer.

- Smith’s work exemplifies characteristics of Romantic poetry such as mysticism, primitivism, and sensibility.

- Smith’s work may be categorized as topographical poetry.

Exercises

- In Sonnet 44, the speaker describes the storm, the “wild blast,” that tears the graves from the cliff. In the final couplet, what does the speaker compare to the storm?

- List some of the nature descriptions in both Sonnet 5 and Sonnet 44. How would you compare/contrast the details in the two poems.

- In Sonnet 44, how does the speaker compare herself to the dead on the beach?

- “Beachy Head” features many of the characteristics considered representative of Romantic poetry. Identify examples of these characteristics.

- List examples of Smith’s identification of nature with supernatural or divine forces.

- In line 4 of “Beachy Head” and in other instances throughout the poem, the speaker refers to Fancy. Until Samuel Taylor Coleridge distinguished between fancy and imagination in his 1817 Biographia Literaria, the term fancy was considered to mean essentially the same creative function as imagination. Coleridge, however, defined fancy as a lower order skill: simply recalling events, reordering and arranging memories and impressions but not creating new meaning. Imagination he considered a much higher order skill involving creativity. Consider Smith’s use of the term Fancy. Which definition do you think she intends?

- After describing the natural scene, Smith writes that natural objects are “the toys of Nature” that have little value “in Reason’s eye.” How does this comment relate to the 18th-century Enlightenment view of Reason? Do you find an implied criticism of the veneration of Reason in this poem?

- In “Beachy Head,” Smith describes “Heaven’s pure air” blowing through nature to produce the music of nature. Compare this image to the principal image in Coleridge’s “The Eolian Harp.”

Resources

General Information

- British Women Romantic Poets 1789–1832. An Electronic Collection of Texts from the University of California at Davis.

Biography

- “Charlotte Smith.” Romantic Natural History. Ashton Nichols. Dickinson College.

- “Charlotte (Turner) Smith (1749–1806).” Women Writers. Library and Early Women’s Writing. Chawton House Library.

- “Introduction.” The Works of Charlotte Smith—An Electronic Edition. Stephen C. Behrendt. Electronic Text Center, UNL Libraries. University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

Texts

- “Beachy Head with Other Poems.” British Women Romantic Poets, 1789–1832. An Electronic Collection of Texts from the University of California at Davis. Ophilia Yim.

- “Beachy Head: With Other Poems.” Google Books.

- “Charlotte Turner Smith.” The Works of Charlotte Smith—An Electronic Edition. Stephen C. Behrendt. Electronic Text Center, UNL Libraries. University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

- “Elegiac Sonnets.” British Women Romantic Poets, 1789–1832. An Electronic Collection of Texts from the University of California at Davis. Charlotte Payne.

- “Elegiac Sonnets: by Charlotte Smith With Additional Sonnets and Other Poems.” Google Books.

Audio

- “Charlotte Smith.” Eighteenth-Century Audio: A Collection of Aural Poetry.

- “Elegiac Sonnets and Other Poems.” LibriVox.

6.3 William Blake (1757–1827)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize William Blake as both artist and writer, and assess the integration of his writing with his art.

- Interpret Blake’s title Songs of Innocence and Experience, and differentiate the state of innocence and the state of experience in the correlating pairs of poems.

- Evaluate Songs of Innocence and Experience as examples of Romantic poetry.

Biography

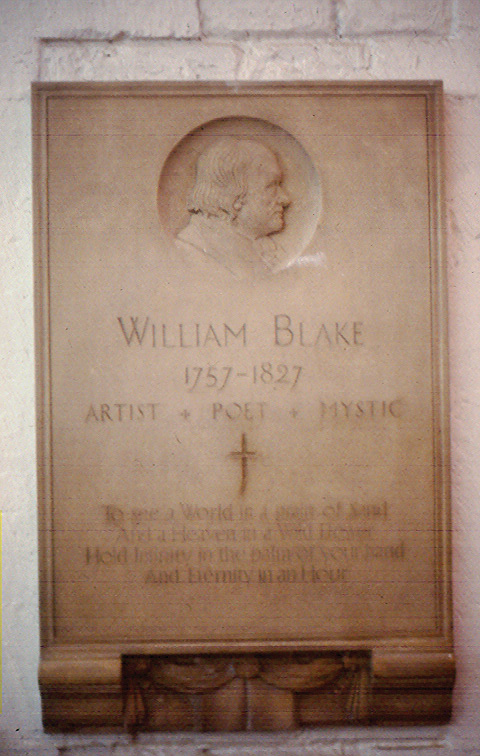

William Blake‘s memorial plaque in St. Paul’s Cathedral, London, identifies him as an “artist, poet, mystic.” Born in London, where he spent most of his life, Blake was educated largely at home. From his childhood he claimed to experience visions of and even conversations with angels and with the Virgin Mary. His visionary experiences appear in many of his poetic works, such as The Book of Urizen and The Book of Los.

For a short time, Blake attended art school and then was apprenticed to an engraver. He made his living primarily from his artwork. His poetry, such as Songs of Innocence and Experience, was written as an integral part of his engravings.

William Blake Memorial Plaque

William Blake’s memorial plaque in St. Paul’s Cathedral, London including the first stanza of Blake’s “Auguries of Innocence.”

William Blake

1757–1827

Artist + Poet + Mystic

“To see a world in a grain of sand

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand

And eternity in an hour.”

The British Library includes Blake’s Notebook in its Virtual Books collection. On pages 29 and 30, you can see a draft copy of “The Tyger” and on page 3, sketches of tigers. The William Blake Archive provides digital images of Songs of Innocence and Experience and of Blake’s other poetic works that allow you to read the works as Blake intended, with the accompanying engravings.

Texts

- The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Blake Digital Text Project. David V. Erdman, ed. Nelson Hilton. University of Georgia, Athens.

- Selected Poetry of William Blake. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English. University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- Songs of Innocence and Experience by William Blake. Project Gutenberg.

Illustrated Text

- “Songs of Innocence 1789.” The William Blake Archive. Editors: Morris Eaves, University of Rochester; Robert Essick, University of California, Riverside; Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library of Congress.

- “Songs of Innocence and Experience.” The William Blake Archive. Editors: Morris Eaves, University of Rochester; Robert Essick, University of California, Riverside; Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library of Congress.

- “William Blake Online.” Tate Britain.

Songs of Innocence and Experience

Although Blake is considered a pre-Romantic poet, his poetry exhibits many of the characteristics of Romantic poetry.

Like many late 18th-century and 19th-century writers, Blake abhorred the effects the Industrial Revolution had on the physical environment and, more importantly, on the people caught in a time of radical change in the ways of living and making a living their families had pursued for generations. Child labor issues figure prominently in Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience. The Victorian Web’s section on child labor includes testimony from 1819 Parliamentary hearings on the Chimney Sweepers’ Regulation Bill. With his Romantic sensibility, Blake puts a human face on the debate, encouraging the reader to think of the situation in terms of individuals—Tom, Dick, Joe, Ned, and Jack—innocent children living lives of inhumane hardship.

Key Takeaways

- William Blake created his poetry as an integral part of his artwork.

- Blake’s title pinpoints the dichotomy between the states of innocence and of experience that, according to the work’s subtitle, characterize the human soul.

- Although often considered a pre-Romantic poet, Blake’s work exemplifies many characteristics of Romantic poetry.

Exercises

-

Blake titles his collection of poems Songs of Innocence and Experience. His subtitle explains that the poems are “Shewing [showing] the Two Contrary [opposite] States of the Human Soul.” Both “innocence” and “experience” are part of each human soul.

- What do you think he means when he uses the terms “innocence” and “experience”?

- Do “innocence” and “experience” belong to certain ages of a person’s life, or to one’s attitude about life, or to the experiences that happen to a person in life, or other circumstances?

-

After reading all of the Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience, re-read the following pairs of poems as companion poems:

- “The Lamb” and “The Tyger”

- “The Chimney Sweeper” and “The Chimney Sweeper”

- “Holy Thursday” and “Holy Thursday”

- “Nurse’s Song” and “Nurse’s Song”

Why does the first poem of each pair belong in the innocence category and the second in the experience category?

- While “The Lamb” is a question and answer poem, its companion “The Tyger” is only a question poem. Why?

-

In “The Lamb,” who does the speaker refer to in the following lines?

He is called by thy name,

For he calls himself a Lamb:

He is meek & he is mild,

He became a little child:

- In the Innocence “The Chimney Sweeper,” why does Tom dream of being locked in “coffins of black”? Note how the young boys imagine Heaven; how does this add to the pathos of the poem? Explain the final line of the poem: “So if all do their duty they need not fear harm”; to whom does the speaker refer with the word “all”?

- In the Experience “The Chimney Sweeper,” who does the boy seem to blame for his situation?

-

In the Innocence “Holy Thursday,” the poem describes an apparently beautiful sight: the poor children of London cleaned up and dressed in their best clothing being marched to a church service to sing praises. In the Experience “Holy Thursday,” the poem begins with a question:

Is this a holy thing to see

In a rich and fruitful land,

Babes reduced to misery,

Fed with cold and usurous hand?

What is the relationship of the two poems?

- What characteristics of Romanticism do you find in Songs of Innocence and Experience?

Resources

General Information

- The William Blake Archive. Editors: Morris Eaves, University of Rochester; Robert Essick, University of California, Riverside; Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library of Congress.

Biography

- “About Blake.” The Blake Society.

- “Chronology.” The William Blake Archive. Editors: Morris Eaves, University of Rochester; Robert Essick, University of California, Riverside; Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library of Congress.

- William Blake (1757–1827). The British Museum.

- “William Blake (1757–1827).” Denise Vultee. The William Blake Archive. Editors: Morris Eaves, University of Rochester; Robert Essick, University of California, Riverside; Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library of Congress.

Songs of Innocence and Experience

- Blake, Songs of Innocence and Experience, 1794. British Library.

Texts

- The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Blake Digital Text Project. David V. Erdman, ed. Nelson Hilton, University of Georgia, Athens.

- Selected Poetry of William Blake. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English. University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- Songs of Innocence and Experience by William Blake. Project Gutenberg.

Illustrated Texts

- “Songs of Innocence 1789.” The William Blake Archive. Editors: Morris Eaves, University of Rochester; Robert Essick, University of California, Riverside; Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library of Congress.

- “Songs of Innocence and Experience.” The William Blake Archive. Editors: Morris Eaves, University of Rochester; Robert Essick, University of California, Riverside; Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library of Congress.

- “William Blake Online.” Tate Britain.

Audio

- Allen Ginsberg Performing William Blake. Naropa University Archive Project. Internet Archive.

- Songs of Innocence and Experience. LibriVox.

- Songs of Innocence and Experience by Blake. Project Gutenberg.

- “Stefanie Wortman Reads ‘The Chimney Sweeper’ [from Songs of Experience] by William Blake.” Poets on Poets. Ed. Tilar Mazzeo. Romantic Circles. General Editors: Neil Fraistat and Steven E. Jones. Technical Editor: Laura Mandell. University of Maryland. audio and text.

- “William Blake.” The Romantics. BBC. selected poems.

Art Information

- “Blake’s Notebooks.” Virtual Books. British Library.

- “Illuminated Printing.” The William Blake Archive. Editors: Morris Eaves, University of Rochester; Robert Essick, University of California, Riverside; Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library of Congress.

- “William Blake and the Illuminated Book.” The Electronic Labyrinth. Christopher Keep, Tim McLaughlin, Robin Parmar. Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities. University of Virginia.

Concordance

- Concordance to The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Blake Digital Text Project. Nelson Hilton, University of Georgia, Athens.

- “William Blake Songs of Innocence and Experience Web Concordance.” The Web Concordances.

6.4 Robert Burns (1759–1796)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Understand Robert Burns’s position as the national poet of Scotland and his appeal to Romantic-era audiences as a natural poet, an example of primitivism.

- Identify characteristics of Romanticism in Burns’s poetry.

Duyckinick, Evert A. Portrait Gallery of Eminent Men and Women in Europe and America.

New York: Johnson, Wilson & Company, 1873.

Robert Burns is the national poet of Scotland. Although his poems are somewhat difficult to read because of the Scottish dialect, that dialect is one of the reasons Burns is a central pre-Romantic figure. Long before the popularity of 20th-century multi-culturalism, Burns preserved in his poetry the Scottish language, culture, and heritage. Burns embodies the concept of Romantic primitivism, and his poetry exemplifies the glorification of the common man, the individual educated by life and nature.

Biography

The son of a Scottish farmer, Robert Burns was born in this farmhouse in Alloway, Scotland in 1759. One end of the building housed the animals; the other, the family.

Burns attended the local school, had occasional tutors, and read voraciously. Because he lacked formal education, he was viewed as a natural poet, the exemplification of a Romantic ideal: a primitive plowman, close to nature, as capable of writing perceptive poetry as the university-educated aristocrat. After the publication of his Kilmarnock volume of poetry, Burns’s fame soared, and he was in demand in the highest social circles in Scotland.

Known as the National Poet of Scotland, Robbie Burns celebrated the folk legends, the history, and the language of Scotland. His poetry also glorified nature, the common individual, and rural Scottish life.

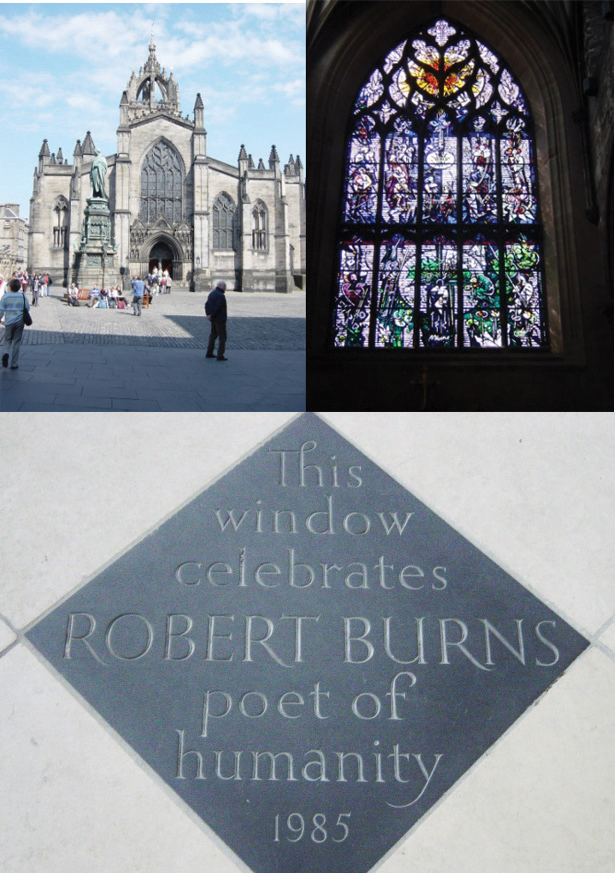

A stained glass window in St. Giles Church in Edinburgh, Scotland honors Burns, as do numerous monuments in Edinburgh, Alloway, and Dumfries where Burns lived.

Texts

- Books by Robert Burns. Project Gutenberg.

- Complete Works. Burns Country. includes glossary for Scottish words.

- Selected Poetry of Robert Burns. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

Audio

In addition to reading Burns’s poetry, listen to recordings in the Scottish dialect.

- “Kevin McFadden Reads ‘To a Mouse’ by Robert Burns.” Poets on Poets. Tilar Mazzeo, ed. Romantic Circles.

- “Robert Burns 250th Anniversary Collection.” LibriVox.

The Poetic Genius of my Country found me at the plough and threw her inspiring mantle over me. She bade me sing the loves, the joys, the rural scenes and rural pleasures of my native soil, in my native tongue; I tuned my wild, artless notes, as she inspired

…—quotation from a letter by Robert Burns.

“To a Mouse” and “To a Louse”

Both “To a Mouse” and “To a Louse” have a moral to the story.

In “To a Mouse,” a farmer plowing his field turns up a mouse’s nest, and the poem reports his speech to the mouse. Sympathetic, the farmer recognizes what was a popular idea among Romantic poets, the idea of man and nature in a “social union.” In Burns’s frequently quoted lines, the farmer states that even the most careful plans may “go astray” because of unforeseen circumstances:

The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy!

In the final stanza, the farmer notes, despite this realization that neither man nor mouse can plan the future with any certainty, the mouse is still more blessed than the man. The present only affects the mouse; people, however, look back at the past and worry about the future.

Auld Kirk in Alloway, setting of Tam O’Shanter’s ghostly encounter.

In “To a Louse,” the moral is in lines 43–44 as Burns laments that people might behave differently if only we could see ourselves in the same way that others see us. The method he chooses to convey this message is by relating the story of Jeany, a young woman sitting in a church service, aware that people are staring at her. Thinking they are admiring her bonnet and her beauty, Jeany is unaware that they really are watching a louse making its way across her bonnet. The narrator believes that lice belong on poor beggars, not on fine ladies. The louse, however, by its presence on Jeany makes the point that nature is indifferent to social status.

“Tam O’Shanter”

Robert Burns sets his folktale “Tam O’Shanter” in his hometown of Alloway. The story tells of a foolish, drunken man who, to his detriment, ignores the good advice of his wife, stays out late drinking too much, and suffers, as does his brave horse Meg, a supernatural encounter.

Video Clip 3

Robert Burns Tam O’Shanter

(click to see video)View a video mini-lecture on “Tam O’Shanter.”

Key Takeaways

- Robert Burns is the National Poet of Scotland because he celebrated his country’s language, folklore, and rural life.

- Burns’s reputation as a natural poet epitomized the Romantic-era ideal of primitivism.

Exercises

- What characteristics of Romantic poetry do you find in “To a Mouse” and “To a Louse”?

- How would you describe the character Tam O’Shanter?

- Who is Maggie (also referred to as Meg)? What did Maggie lose in her flight to save Tam O’Shanter?

- What alerted the witches to Tam’s presence?

- Whom would you describe as the hero of “Tam O’Shanter”?

- What is the “moral” of “Tam O’Shanter”?

- How does Burns’s telling of “Tam O’Shanter” correspond with Romantic ideas about poetry and poets?

Resources

General Information

- The Burns Encyclopedia. Burns Country. Maurice Lindsey.

- “Robert Burns and Radicalism.” The Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution. BBC History.

Biography

- “Burns Timeline.” Robert Burns Birthplace Museum. National Trust for Scotland.

- Robert Burns 1759–1796. National Library of Scotland Digital Gallery.

- Robert Burns, 1759–1796. University of South Carolina Libraries. Rare Books and Special Collections. Biographical information with images of manuscripts.

- Robert Burns Biography. BBC Scotland.

Texts

- Books by Robert Burns. Project Gutenberg.

- Complete Works. Burns Country. includes glossary of Scottish words.

- Selected Poetry of Robert Burns. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

Audio

- “Kevin McFadden Reads ‘To a Mouse’ by Robert Burns.” Poets on Poets. Ed. Tilar Mazzeo. Romantic Circles. General Editors: Neil Fraistat and Steven E. Jones. Technical Editor: Laura Mandell. University of Maryland.

- “Robert Burns 250th Anniversary Collection.” LibriVox.

Video

- “Robert Burns.” Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.

- “Robert Burns, ‘Tam O’Shanter.’” Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.

6.5 Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize the unconventional nature of Mary Wollstonecraft’s beliefs, as expressed in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman for her time period.

- Correlate the opinions expressed in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman with the characteristics of Romanticism.

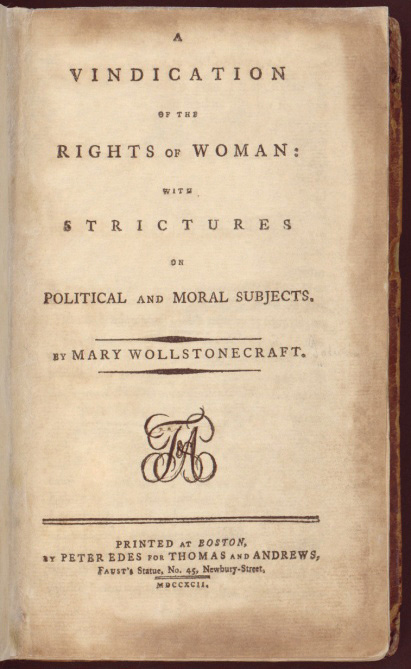

The same philosophy that led to the American Revolution and the French Revolution, the impetus for equality that was a focusing tenet of Romanticism, led many to believe that women should be included in the granting of political and social rights. Although Mary Wollstonecraft wrote novels, she is best remembered for her political treatises such as A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

James Heath (1757–1834), engraved from the painting of John Opie (1761–1807).

Biography

Wollstonecraft’s personal experiences mirror the state of women’s rights in the late 18th/early 19th centuries. As the second child, Mary Wollstonecraft from early childhood resented her elder brother’s education and inheritance. Denied the formal education her brother enjoyed, Wollstonecraft, through her reading, obtained an education equal to or perhaps better than many women of her time period and social class. Because of her father’s declining financial situation, Wollstonecraft earned her own living, working in the only jobs available to women, such as a lady’s companion and a governess, which she found particularly distasteful. Later in her life she attempted to establish schools for girls.

In her personal life as well as her professional life, Wollstonecraft was unconventional and attracted the disdain of traditional society. She gave birth to an illegitimate daughter, allowing people to believe she was married to the child’s father.

Portrait by John Opie.

Wollstonecraft’s two suicide attempts testify to her dissatisfaction with life in a world which disagreed so adamantly with her ideas of radical freedom in moral and social behavior. Later when she became pregnant with William Godwin‘s child, they married, even though both advocated free love without marriage. The couple’s marriage revealed that Wollstonecraft’s first marriage was a pretense, and she again found herself publicly ostracized. Wollstonecraft died from complications of childbirth a month after her daughter with Godwin was born. Their daughter, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, grew up to marry the poet Shelley and to write the novel Frankenstein.

Text of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

- 1792 A Vindication of the Rights of Women by Mary Wollstonecraft. Great Voyages: The History of Western Philosophy from 1492 to 1776. Bill Uzgalis, Oregon State University. searchable text.

- “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects.” Bartleby.com. rpt. from Boston: Peter Edes, 1792.

- “Modern History Sourcebook: Mary Woolstonecraft [sic]: A Vindication of the Right of Women.” Internet Modern History Sourcebook. Paul Halsall, Fordham University.

- Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft. Project Gutenberg.

- “Wollstonecraft, Mary, 1759–1797 . A Vindication of the Rights of Woman / by Mary Wollstonecraft.” Electronic Text Center. University of Virginia Library.

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

Excerpt from the Introduction

After considering the historic page, and viewing the living world with anxious solicitude, the most melancholy motions of sorrowful indignation have depressed my spirits, and I have sighed when obliged to confess, that either nature has made a great difference between man and man, or that the civilization, which has hitherto taken place in the world, has been very partial. I have turned over various books written on the subject of education, and patiently observed the conduct of parents and the management of schools; but what has been the result? a profound conviction, that the neglected education of my fellow creatures is the grand source of the misery I deplore; and that women in particular, are rendered weak and wretched by a variety of concurring causes, originating from one hasty conclusion. The conduct and manners of women, in fact, evidently prove, that their minds are not in a healthy state; for, like the flowers that are planted in too rich a soil, strength and usefulness are sacrificed to beauty; and the flaunting leaves, after having pleased a fastidious eye, fade, disregarded on the stalk, long before the season when they ought to have arrived at maturity. One cause of this barren blooming I attribute to a false system of education, gathered from the books written on this subject by men, who, considering females rather as women than human creatures, have been more anxious to make them alluring mistresses than rational wives; and the understanding of the sex has been so bubbled by this specious homage, that the civilized women of the present century, with a few exceptions, are only anxious to inspire love, when they ought to cherish a nobler ambition, and by their abilities and virtues exact respect.

In a treatise, therefore, on female rights and manners, the works which have been particularly written for their improvement must not be overlooked; especially when it is asserted, in direct terms, that the minds of women are enfeebled by false refinement; that the books of instruction, written by men of genius, have had the same tendency as more frivolous productions; and that, in the true style of Mahometanism, they are only considered as females, and not as a part of the human species, when improvable reason is allowed to be the dignified distinction, which raises men above the brute creation, and puts a natural sceptre in a feeble hand.

Yet, because I am a woman, I would not lead my readers to suppose, that I mean violently to agitate the contested question respecting the equality and inferiority of the sex; but as the subject lies in my way, and I cannot pass it over without subjecting the main tendency of my reasoning to misconstruction, I shall stop a moment to deliver, in a few words, my opinion. In the government of the physical world, it is observable that the female, in general, is inferior to the male. The male pursues, the female yields—this is the law of nature; and it does not appear to be suspended or abrogated in favour of woman. This physical superiority cannot be denied—and it is a noble prerogative! But not content with this natural pre-eminence, men endeavour to sink us still lower, merely to render us alluring objects for a moment; and women, intoxicated by the adoration which men, under the influence of their senses, pay them, do not seek to obtain a durable interest in their hearts, or to become the friends of the fellow creatures who find amusement in their society.

I am aware of an obvious inference: from every quarter have I heard exclamations against masculine women; but where are they to be found? If, by this appellation, men mean to inveigh against their ardour in hunting, shooting, and gaming, I shall most cordially join in the cry; but if it be, against the imitation of manly virtues, or, more properly speaking, the attainment of those talents and virtues, the exercise of which ennobles the human character, and which raise females in the scale of animal being, when they are comprehensively termed mankind—all those who view them with a philosophical eye must, I should think, wish with me, that they may every day grow more and more masculine.

This discussion naturally divides the subject. I shall first consider women in the grand light of human creatures, who, in common with men, are placed on this earth to unfold their faculties; and afterwards I shall more particularly point out their peculiar designation.

I wish also to steer clear of an error, which many respectable writers have fallen into; for the instruction which has hitherto been addressed to women, has rather been applicable to LADIES, if the little indirect advice, that is scattered through Sandford and Merton, be excepted; but, addressing my sex in a firmer tone, I pay particular attention to those in the middle class, because they appear to be in the most natural state. Perhaps the seeds of false refinement, immorality, and vanity have ever been shed by the great. Weak, artificial beings raised above the common wants and affections of their race, in a premature unnatural manner, undermine the very foundation of virtue, and spread corruption through the whole mass of society! As a class of mankind they have the strongest claim to pity! the education of the rich tends to render them vain and helpless, and the unfolding mind is not strengthened by the practice of those duties which dignify the human character. They only live to amuse themselves, and by the same law which in nature invariably produces certain effects, they soon only afford barren amusement.

But as I purpose taking a separate view of the different ranks of society, and of the moral character of women, in each, this hint is, for the present, sufficient; and I have only alluded to the subject, because it appears to me to be the very essence of an introduction to give a cursory account of the contents of the work it introduces.

My own sex, I hope, will excuse me, if I treat them like rational creatures, instead of flattering their FASCINATING graces, and viewing them as if they were in a state of perpetual childhood, unable to stand alone. I earnestly wish to point out in what true dignity and human happiness consists—I wish to persuade women to endeavour to acquire strength, both of mind and body, and to convince them, that the soft phrases, susceptibility of heart,

delicacy of sentiment, and refinement of taste, are almost synonymous with epithets of weakness, and that those beings who are only the objects of pity and that kind of love, which has been termed its sister, will soon become objects of contempt.

Dismissing then those pretty feminine phrases, which the men condescendingly use to soften our slavish dependence, and despising that weak elegancy of mind, exquisite sensibility, and sweet docility of manners, supposed to be the sexual characteristics of the weaker vessel, I wish to show that elegance is inferior to virtue, that the first object of laudable ambition is to obtain a character as a human being, regardless of the distinction of sex; and that secondary views should be brought to this simple touchstone.

This is a rough sketch of my plan; and should I express my conviction with the energetic emotions that I feel whenever I think of the subject, the dictates of experience and reflection will be felt by some of my readers. Animated by this important object, I shall disdain to cull my phrases or polish my style—I aim at being useful, and sincerity will render me unaffected; for wishing rather to persuade by the force of my arguments, than dazzle by the elegance of my language, I shall not waste my time in rounding periods, nor in fabricating the turgid bombast of artificial feelings, which, coming from the head, never reach the heart. I shall be employed about things, not words! and, anxious to render my sex more respectable members of society, I shall try to avoid that flowery diction which has slided from essays into novels, and from novels into familiar letters and conversation.

These pretty nothings, these caricatures of the real beauty of sensibility, dropping glibly from the tongue, vitiate the taste, and create a kind of sickly delicacy that turns away from simple unadorned truth; and a deluge of false sentiments and over-stretched feelings, stifling the natural emotions of the heart, render the domestic pleasures insipid, that ought to sweeten the exercise of those severe duties, which educate a rational and immortal being for a nobler field of action.

The education of women has, of late, been more attended to than formerly; yet they are still reckoned a frivolous sex, and ridiculed or pitied by the writers who endeavour by satire or instruction to improve them. It is acknowledged that they spend many of the first years of their lives in acquiring a smattering of accomplishments: meanwhile, strength of body and mind are sacrificed to libertine notions of beauty, to the desire of establishing themselves, the only way women can rise in the world—by marriage. And this desire making mere animals of them, when they marry, they act as such children may be expected to act: they dress; they paint, and nickname God’s creatures. Surely these weak beings are only fit for the seraglio! Can they govern a family, or take care of the poor babes whom they bring into the world?

Title page from the first American edition 1792.

Key Takeaways

- Because of the strictures of her society, Mary Wollstonecraft was largely self-educated and forced to work in traditional women’s jobs which she disliked.

- Wollstonecraft evinces the Romantic characteristics of primitivism and individualism as well as exemplifying tenets from Wordsworth’s Preface to Lyrical Ballads such as the use of common language and writing for and about common people.

Exercises

- In the first paragraph of A Vindication, Wollstonecraft uses an analogy to illustrate the thesis of her essay: she compares women as they are treated by society to flowers. What is the purpose of this analogy?

- This analogy leads her to the thesis of her essay. Identify her thesis.

- In paragraph six, Wollstonecraft specifies her audience. To what group of women is she writing? Why does she choose that group of women?

- How, in paragraph 8, does Wollstonecraft say women usually are treated, and how does she plan to be different?

- What type of language does Wollstonecraft intend to use in her essay? Compare her choice of language to that advocated by Wordsworth in his 1802 Preface to Lyrical Ballads.

- Wollstonecraft argues that because women are not educated they have only one means to “rise in the world.” What is that means?

Resources

General Information

- “Wollstonecraft’s Rights of Woman.” Taking Liberties: The Struggle for Britain’s Freedoms and Rights. British Library.

Biography

- “Mary Wollstonecraft.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Sylvana Tomaselli, Stanford University.

- “Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797).” Shelley’s Ghost: Reshaping the Image of a Literary Family. Bodleian Libraries. Oxford University Exhibit in partnership with the New York Public Library.

- “Mary Wollstonecraft, 1759–1797.” The History Guide. Steven Kreis. Lectures on Modern European Intellectual History.

- “Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797).” Chawton House Library. Valerie Patten. Library and Early Women’s Writing. Women Writers.

- “Mary Wollstonecraft: A ‘Speculative and Dissenting Spirit.’” Janet Todd, University of Glasgow. British History. BBC History. BBC.

- “Wollstonecraft Time Line.” Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797). Bill Uzgalis, Oregon State University.

Text

- 1792 A Vindication of the Rights of Women by Mary Wollstonecraft. Great Voyages: The History of Western Philosophy from 1492 to 1776. Bill Uzgalis, Oregon State University. searchable text.

- “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects.” Bartleby.com. rpt. from Boston: Peter Edes, 1792.

- “Modern History Sourcebook: Mary Woolstonecraft [sic]: A Vindication of the Rights of Women.” Internet Modern History Sourcebook. Paul Halsall, Fordham University.

- Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft. Project Gutenberg.

- “Wollstonecraft, Mary, 1759–1797 . A Vindication of the Rights of Woman / by Mary Wollstonecraft.” Electronic Text Center. University of Virginia Library.

Audio

- Mary Wollstonecraft’s Last Three Notes to Godwin. Shelley’s Ghost: Reshaping the Image of a Literary Family. Bodleian Libraries. Oxford University Exhibit in partnership with the New York Public Library. podcast read by Oxford University students.

- Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication. Shelley’s Ghost: Reshaping the Image of a Literary Family. Bodleian Libraries. Oxford University Exhibit in partnership with the New York Public Library. podcast read by Oxford University students.

- A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. LibriVox.

- A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Shelley’s Ghost: Reshaping the Image of a Literary Family. Bodleian Libraries. Oxford University Exhibit in partnership with the New York Public Library. podcast read by Oxford University students.

- A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft. Project Gutenberg.

- “Wollstonecraft and Women’s Rights.” Taking Liberties: The Struggle for Britain’s Freedoms and Rights. Barbara Taylor. British Library. lecture on Wollstonecraft’s influence on British political rights for women.

Women’s Rights

- Introduction. Abby Wolf, Harvard University. 19th Century Women Writers. PBS.

- “Women’s Lives in Eighteenth Century England.” Miami University, Oxford, Ohio.

- “Wollstonecraft and Women’s Rights.” Taking Liberties: The Struggle for Britain’s Freedoms and Rights. Barbara Taylor. British Library. lecture on Wollstonecraft’s influence on British political rights for women.

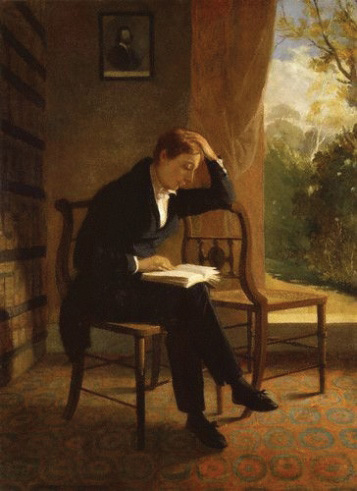

6.6 William Wordsworth (1770–1850)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Charlotte Smith, William Blake, and Robert Burns are sometimes referred to as pre-Romantic writers. Although their works display the characteristics of Romantic poetry, they pre-date Wordsworth and Coleridge, whose work is considered the beginning of British Romantic literature.

Biography

View the presentation on Wordsworth’s biography. Also view video mini-lectures Romanticism and Wordsworth and William Wordsworth.

Texts

- Books by William Wordsworth. Project Gutenberg.

- The Complete Poetical Works. William Wordsworth. rpt. from London: Macmillan, 1888. Bartleby.com.

- Lyrical Ballads: An Electronic Scholarly Edition. Romantic Circles. General Editors: Neil Fraistat, Steven E. Jones. Technical Editor: Laura Mandell. University of Maryland.

- “William Wordsworth.” Dove Cottage and the Wordsworth Museum. The Wordsworth Trust. selected poems with commentary.

- Wordsworth Variorum Archive. James M. Garrett, California State University at Los Angeles. texts from published first editions and concordance.

“Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey”

With the passage of the 1534 Act of Supremacy, King Henry VIII ordered that selected monasteries and abbeys in England be closed and the occupants dispersed. Like many others, Tintern Abbey stood vacant and gradually fell into decay. Over two hundred years later, Wordsworth came upon the ruins of Tintern Abbey while on a hiking trip. In the opening lines of the poem, the speaker states that after five years he has returned to Tintern Abbey.

Video Clip 4

Wordsworth’s Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey

(click to see video)View a video mini-lecture on “Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey.”

“Lines” is an example of a pattern found in much Romantic poetry: an observation of nature followed by a meditation inspired by that observation.

The following are excerpts from “Lines,” not the entire poem.

Stanza 1 (lines 1–22): the speaker describes the beautiful scene. Note the descriptive details. This stanza is the observation of nature.

| Five years have past; five summers, with the length | |

| Of five long winters! and again I hear | |

| These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs | |

| With a soft inland murmur.—Once again | |

| Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs, | 5 |

| That on a wild secluded scene impress | |

| Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect | |

| The landscape with the quiet of the sky. | |

| The day is come when I again repose | |

| Here, under this dark sycamore, and view | 10 |

| These plots of cottage-ground, these orchard-tufts, | |

| Which at this season, with their unripe fruits, | |

| Are clad in one green hue, and lose themselves | |

| ‘Mid groves and copses. Once again I see | |

| These hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines | 15 |

| Of sportive wood run wild: these pastoral farms, | |

| Green to the very door; and wreaths of smoke | |

| Sent up, in silence, from among the trees! | |

| With some uncertain notice, as might seem | |

| Of vagrant dwellers in the houseless woods, | 20 |

| Or of some Hermit’s cave, where by his fire | |

| The Hermit sits alone. |

Stanza 2 (lines 22–49): This stanza begins the meditation—a philosophical strain of thought inspired by the natural scene. The speaker realizes that although he hasn’t seen Tintern Abbey for five years, he has remembered the beautiful scene even when he’s back in the busy, noisy city enduring the stress of daily life. When he remembers the beauty of nature, he feels again the calmness, the “tranquil restoration,” of being in nature. This idea that nature, even the memory of nature, can cause us to feel tranquil is a central concept of Romanticism.

| These beauteous forms, |

| Through a long absence, have not been to me |

| As is a landscape to a blind man’s eye: |

| But oft, in lonely rooms, and ‘mid the din |

| Of towns and cities, I have owed to them |

| In hours of weariness, sensations sweet, |

| Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart; |

| And passing even into my purer mind, |

| With tranquil restoration:—feelings too |

| Of unremembered pleasure: such, perhaps, |

| As have no slight or trivial influence |

| On that best portion of a good man’s life, |

| His little, nameless, unremembered, acts |

| Of kindness and of love. |

Stanza 4 (lines 58–111): The speaker reiterates the same concept in lines 64–67. He realizes that while he stands looking at the beauty of Tintern Abbey he is receiving two types of pleasure: first, the “present pleasure” of simply enjoying the beauty at the moment; and second, the pleasure of storing up mental “life and food for future years” when he returns to the city and calls up the scene in his memory.

| While here I stand, not only with the sense | |

| Of present pleasure, but with pleasing thoughts | 65 |

| That in this moment there is life and food | |

| For future years. |

Later in stanza 4, the speaker explains why remembering the beauties of nature can cause him to feel tranquil. First, in lines 90–93, he acknowledges that nature brings to mind “the still, sad music of humanity.” Nature is important because it turns his thoughts to humanity. Second, he informs the reader why nature draws his attention to the needs of humanity. In lines 107–111, he states that in nature he recognizes a divine presence, what he calls “the guide, the guardian of my heart, and soul of all my moral being.” Nature is a means of perceiving a spiritual presence in the world. This passage encapsulates the concept of Romantic mysticism.

| For I have learned | 90 |

| To look on nature, not as in the hour | |

| Of thoughtless youth; but hearing oftentimes | |

| The still, sad music of humanity, | |

| Nor harsh nor grating, though of ample power | |

| To chasten and subdue. And I have felt | 95 |

| A presence that disturbs me with the joy | |

| Of elevated thoughts: a sense sublime | |

| Of something far more deeply interfused, | |

| Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns, | |

| And the round ocean and the living air, | 100 |

| And the blue sky, and in the mind of man: | |

| A motion and a spirit, that impels | |

| All thinking things, all objects of all thought, | |

| And rolls through all things. Therefore am I still | |

| A lover of the meadows and the woods, | 105 |

| And mountains; and of all that we behold | |

| From this green earth; of all the mighty world | |

| Of eye and ear,—both what they half create, | |

| And what perceive; well pleased to recognise | |

| In nature and the language of the sense, | 110 |

| The anchor of my purest thoughts, the nurse, | |

| The guide, the guardian of my heart, and soul | |

| Of all my moral being. |

Stanza 5: The speaker directly addresses his sister (presumably Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy), hoping that she also will recognize both the beauty and the spiritual presence in nature. The benefit of being close to nature is that we are also close to God, and therefore the trials of daily life will not “disturb our cheerful faith.” Note the evils that beset individuals the speaker lists in lines131–134. The speaker trusts his sister will find in nature the same tranquil restoration he has.

| My dear, dear Sister! and this prayer I make | |

| Knowing that Nature never did betray | 125 |

| The heart that loved her; ‘tis her privilege | |

| Through all the years of this our life, to lead | |

| From joy to joy: for she can so inform | |

| The mind that is within us, so impress | |

| With quietness and beauty, and so feed | 130 |

| With lofty thoughts, that neither evil tongues, | |

| Rash judgments, nor the sneers of selfish men, | |

| Nor greetings where no kindness is, nor all | |

| The dreary intercourse of daily life, | |

| Shall e’er prevail against us, or disturb | 135 |

| Our cheerful faith, that all which we behold | |

| Is full of blessings. |

“Michael”

Video Clip 5

William Wordsworth’s Michael A Pastoral Poem

(click to see video)View a video mini-lecture on “Michael.”

“Michael” is a narrative poemA poem that tells a story., a poem that tells a story, about the misfortune of a simple common man and his family. Wordsworth subtitles the poem “A Pastoral Poem.” The term pastoralPoetry about shepherds, sheep, and the simple pleasures of rural life. refers to poetry about shepherds, sheep, and the simple pleasures of rural life. In this poem, Wordsworth not only writes about one individual’s tragedy but also about an entire class of people whose lives are disrupted by the Industrial Revolution. For centuries, many families like Michael’s had made their living from their land and their flocks of sheep. The men tended the sheep and the women spun wool and wove cloth to sell. With the coming of machinery, spinning and weaving could be accomplished much more quickly and cheaply in factories. Many young people, no longer able to make a living in the country, went to work in the cities.

The beginning of the trail which leads to Greenhead Gill[Ghyll], the pathway Wordsworth walked where he saw the “heap of unhewn stone” and was reminded of the story of Michael the shepherd.

A convention of the pastoral mode is the portrayal of life in the city, or in the court as in Marlowe’s poem “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love,” as evil and corrupt—the view of the courtier caught up in and tired of the intrigue and subterfuge of the court, longing to escape into the beautiful, peaceful countryside, totally unaware of the realities of the hard lives of shepherds.

Wordsworth draws on this convention when he pictures the son Luke having to go to the city where he falls into evil and is unable to come home to the pure life of the countryside.

Note the beginning lines of the poem. Wordsworth describes the scene and then focuses our attention on a specific object: “a straggling heap of unhewn stones.” This specific object then, this stack of rough stones, prompts him to remember and to tell us the story of Michael, the shepherd.

The valley between these hills leads to Greenhead Ghyll.

“I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud”

This poem is a lyric poem. Like “Lines,” “I Wandered” follows the pattern of an observation of nature leading to a meditation.

| I wandered lonely as a cloud | |

| That floats on high o’er vales and hills, | |

| When all at once I saw a crowd, | |

| A host, of golden daffodils; | |

| Beside the lake, beneath the trees, | |

| Fluttering and dancing in the breeze. | |

| Continuous as the stars that shine | |

| And twinkle on the milky way, | |

| They stretched in never-ending line | |

| Along the margin of a bay: | 10 |

| Ten thousand saw I at a glance, | |

| Tossing their heads in sprightly dance. | |

| The waves beside them danced; but they | |

| Out-did the sparkling waves in glee: | |

| A poet could not but be gay, | |

| In such a jocund company: | |

| I gazed—and gazed—but little thought | |

| What wealth the show to me had brought: | |

| For oft, when on my couch I lie | |

| In vacant or in pensive mood, | 20 |

| They flash upon that inward eye | |

| Which is the bliss of solitude; | |

| And then my heart with pleasure fills, | |

| And dances with the daffodils. |

In stanzas 1–3, note the descriptive details. Stanza 4 is the meditation, the part of the poem that is philosophical and thoughtful. In this last stanza, the speaker realizes that when he is at home, lying on his couch, he remembers the sight of the daffodils and he feels the same happy emotions he felt when he originally saw them, an example of “emotion recollected in tranquility” which Wordsworth describes in the Preface to Lyrical Ballads.

Key Takeaways

- The work of Wordsworth and Coleridge is considered the beginning of the Romantic Period in British literature.

- The landscape of the Lake District influenced Wordsworth’s poetry.

- The pattern of an observation of nature that leads into a meditation is a typical pattern in Romantic poetry.

- “Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey,” first published in Lyrical Ballads, exemplifies the tenets of Romanticism Wordsworth outlined in the 1802 Preface and provides an explanation of Romantic mysticism.

- “Michael” addresses the consequences of the Industrial Revolution on the English countryside and its inhabitants.

Exercises

- What does the poem’s narrator see that reminds him of the story of Michael?

- In what ways is “Michael” a pastoral poem?

- Describe Michael’s relationship with Luke.

- Why does Luke go to the city?

- Why does Michael have Luke begin laying stones for the sheepfold before he leaves? Identify biblical allusions in this section of the poem. What purpose do these allusions serve?

- What happens to Luke in the city? What happens to Michael and Isabel at the end of the story? What happens to the land Michael tried to save?

- In your opinion, did Michael make the right decision in sending Luke to the city? Why or why not?

- Compare stanza 4 of “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” with lines 62–65 of “Tintern Abbey.” What similar experience do these two poems describe?

- Identify characteristics of Romanticism in each of these three poems.

- What other Romantic poems follow the pattern of an observation of nature leading into a meditation?

Resources

General Information

- From Goslar to Grasmere. William Wordsworth: Electronic Manuscripts. Dr. Sally Bushell, Lancaster University and Jeff Cowton, Curator, The Wordsworth Trust. Arts and Humanities Research Council. manuscripts, maps, texts, films portraying scenes from the poetry, brief analyses of rhetorical devices.

Biography

- William Wordsworth (1770–1850). Dove Cottage and the Wordsworth Museum. The Wordsworth Trust.

- William Wordsworth (1770–1850). Historic Figures. BBC.

- “William Wordsworth: Biography.” The Victorian Web. Glenn Everett, University of Tennessee at Martin.

- “The Wordsworths and the Cult of Nature.” Pamela Woof, University of Newcastle upon Tyne. British History. BBC.

Texts

- Books by William Wordsworth. Project Gutenberg.

- The Complete Poetical Works. William Wordsworth. rpt. from London: Macmillan, 1888. Bartleby.com.

- Lyrical Ballads: An Electronic Scholarly Edition. Romantic Circles. General Editors: Neil Fraistat, Steven E. Jones. Technical Editor: Laura Mandell. University of Maryland.

- “William Wordsworth.” Dove Cottage and the Wordsworth Museum. The Wordsworth Trust. selected poems with commentary.

- Wordsworth Variorum Archive. James M. Garrett, California State University at Los Angeles. texts from published first editions and concordance.

Audio

- “John Casteen Reads ‘Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey’ by William Wordsworth.” Poets on Poets. Ed. Tilar Mazzeo. Romantic Circles. General Editors: Neil Fraistat and Steven E. Jones. Technical Editor: Laura Mandell. University of Maryland. text and audio.

- “Poems by William Wordsworth.” The Romantics. BBC. “The Female Vagrants (extracts), “The Last of the Flock,” “Tintern Abbey.”

- “William Wordsworth.” LibriVox. selected poems.

Concordance

- Wordsworth and Coleridge Lyrical Ballads Web Concordance. Web Concordances.

- Wordsworth Variorum Archive. James M. Garrett. California State University at Los Angeles. texts from published first editions and concordance.

Images

- William Wordsworth Collection, 1799–1847. Princeton University Library. Manuscripts Division. manuscript image.

- “William Wordsworth’s Lake District.” Literary Landscapes. Online Exhibitions. British Library.

Videos

- “Romanticism and Wordsworth.” Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.

- “William Wordsworth’s ‘Michael: A Pastoral Poem.’” Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.

- “William Wordsworth.” Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.

- “Wordsworth’s ‘Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey.’” Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.

6.7 Dorothy Wordsworth (1771–1855)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify tenets of Romanticism in Wordsworth’s journal entries.