This is “The Restoration and Eighteenth Century”, chapter 5 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 5 The Restoration and Eighteenth Century

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

5.1 The Restoration and 18th Century

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify the two key tragedies of 1665–1666 and their effects on the literature of the Restoration era.

- Analyze features of the Enlightenment which distinguish the Age of Reason from preceding time periods and which affect neoclassical literature.

- Characterize the developments of the English language during the 18th century.

- Recognize key forms of literature produced in the Restoration and 18th century.

After the death of Oliver Cromwell, his son Richard Cromwell attempted to assume his father’s leadership position but soon proved unequal to the task. Negotiations began between the English Parliament and the son of the executed King Charles I. In 1660 the monarchy was restored, and Charles II became king. Having escaped to France following his father’s execution, Charles II had found refuge in the court of France, and when he returned to England brought with him a love of an extravagant, frivolous lifestyle that many, accustomed to the Puritan era, found offensive. Others delighted in the less repressive behaviors the new king encouraged.

Great Fire of London by Lieve Pietersz. Verschuier.

Only five years after the Restorationthe reestablishment of the monarch in England after the Puritan Revolution, the reestablishment of the monarch in England after the Puritan Revolution, England suffered an outbreak of plague. Modern estimates suggest that around 100,000 people died in London alone. Then in 1666, the Great Fire of London devastated the city, destroying over 13,000 houses, significant structures such as St. Paul’s Cathedral and the Royal Exchange, many warehouses full of goods, and businesses. The BBC History site allows viewers to see the same two engravings side by side in order to compare the before and after scenes in its “Great Fire of London Skyline Animation.” Luminarium reproduces a painting of London on fire, an engraving of St. Paul’s burning, and a map of the fire’s progress.

The Monument—monument to the Great Fire of London 1666, designed by Christopher Wren.

Some considered these two tragedies acts of God, punishment, according to some, for destroying God’s established order, the Great Chain of Being, by executing the divinely appointed King Charles I. According to others, the punishment was for abandoning the Puritan government and returning a licentious king to power.

Almost immediately suspicion of setting the fire fell upon the Roman Catholics. With memories of the Gunpowder Plot and the religious persecution present since the time of Henry VIII and the Reformation, many Protestants were quick to accuse Catholics of a plot to destroy London.

Queen Mary II and King William III.

Upon the death of Charles II, his brother James succeeded as King James II. Because James had earlier publicly converted to Roman Catholicism, the religious turmoil of the preceding century was renewed. As a result, Parliament forced James II to abdicate the throne and offered the crown to his daughter Mary and her husband, William of Orange. Her uncle King Charles II had arranged Mary’s marriage to William of Orange, whose mother was a sister of Charles II and James II and who was a staunch Protestant. In what was known as the Glorious Revolution, a peaceful revolution, William and Mary replaced James II on the throne and ensured the dominance of the Protestant religion in England. William and Mary also agreed to a stronger role for Parliament in the governing of Great Britain. The age of the absolute monarch had ended.

The Enlightenment

The 18th century was the age of the Enlightenmentthe Age of Reason which emphasized reason, rational thinking, and order or the Age of Reason. In part a reaction against the chaos that had characterized the preceding centuries, Enlightenment thought emphasized reason, rational thinking, and order. One facet of the Enlightenment, the scientific revolution, began at the close of the Middle Ages and marked a profound change in thinking of natural phenomena as events with rational explanations rather than supernatural causes. Empirical observation and the concept of an orderly world, set up by God and run according to His laws of nature, governed philosophical thought as well as the technological development that led to the Industrial Revolution. The British Museum provides an online tour of London in 1753, the year the museum opened, an indication of the interest in science and learning. The online tour includes pictures of early manufacturing in the Industrial Revolution.

The orderly nature of the world was no longer the medieval Great Chain of Being. Instead philosophers began to postulate that all men were created equal and with innate human rights, ideas which led to both the American and French Revolutions in the 18th century. This idea is evident in the English Parliament’s insistence that William and Mary grant more authority to Parliament, the representatives of the English people.

In literature, the Enlightenment appears as neoclassicismliterally means new classicism; emphasizes order, symmetry, elegance, and structure in the arts, including literature, which literally means new classicism and emphasizes order, symmetry, elegance, and structure in the arts, including literature. As apparent in the term neoclassicism, neoclassical writers, artists, and architects looked back to ancient Greece and Rome for classical forms featuring symmetry and geometrical precision in everything from poems to buildings.

Sidebar 5.1.

St. Paul’s Cathedral in London is an example of neoclassical architecture. After the Great Fire of London in 1666, Sir Christopher Wren was commissioned to re-build many of the city’s churches, including St. Paul’s Cathedral. Note the symmetry of the building and the use of columns and the triangular tympanum, all features of classical Greek architecture.

Christopher Wren also remodeled one part of Hampton Court Palace, built during the reign of Henry VIII, for William and Mary. Note the symmetry of Hampton Court Palace in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1

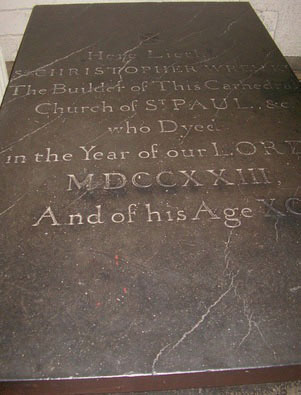

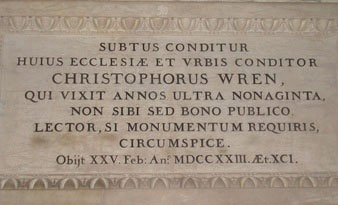

When he died in 1723, Wren was buried in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral. Although it might be expected that one of the world’s most famous architects and the person who designed and personally supervised the building of the Cathedral would have a grand tomb, Wren requested a modest grave site and memorial plaque.

Figure 5.2

The black stone slab in Figure 5.2., located in an inconspicuous corner, covers Wren’s grave. The plaque pictured in Figure 5.3. is located on the wall above the black slab and is engraved with the epitaph: “Reader, if you seek his monument, look around you,” indicating that St. Paul’s Cathedral itself is Wren’s monument.

Figure 5.3

Language

The Restoration and 18th century was a time of standardization of the English language. During the Elizabethan Age, Shakespeare created new words and new expressions, and spelling was erratic. During the early 17th century, the metaphysical poets created elaborate, unusual metaphors. In the 18th century, writers favored a more common sense, prescriptive approach to language. Dr. Samuel Johnson created one of the early and most influential English dictionaries. One of the goals of Johnson’s dictionary was to help create rules of grammar, usage, and spelling previously lacking in the English language, an idea in line with the preference for structure that characterized neoclassicism and with the scientific approach to all subjects typical of the Age of Reason. Although the feudal system had long ago faded into the past, British society of the 18th century maintained a strict social class system reflected in the language.

Literature

Restoration Drama

With the Restoration of the monarchy came the restoration of the theater. After being shuttered during the Puritans’ rule, theatres opened almost immediately. Charles II hired companies of actors to provide court entertainment, as his grandfather James I had been patron of Shakespeare’s troop The King’s Men. Plays from the Elizabethan Age were revived and new dramatists emerged although none produced work of the high caliber of Shakespeare’s age. Among the new generation of playwrights were several women, most notably Aphra Behn. Another innovation in 18th-century theater was that women were allowed on stage.

During the 18th century, the comedy of mannersa play which presents aristocratic characters, exaggerating their obsession with high society manners, social position, fashion, and wealth, a play which presents aristocratic characters, exaggerating their obsession with high society manners, social position, fashion, and wealth, flourished. These plays are noted for their witty dialogue and satiric manner. The plots generally involve amorous, usually scandalous, affairs and the characters’ amoral reactions to them. Familiar stock characters were the fop or dandy, a vain young man obsessed with fashion, and the rake, a young man devoted to wine, women, and scandalous conduct. Richard Sheridan’s “The Rivals” and “The School for Scandal” and Oliver Goldsmith’s “She Stoops to Conquer” were among the more popular comedies of manners.

The Novel

The 18th century gave birth to the novelan extended fictional prose narrative, an extended fictional prose narrative, as a form of literature. Daniel DeFoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders are considered the first novels. DeFoe’s works were followed by Samuel Richardson’s epistolary novela novel written in the form of a series of letters (a novel written in the form of a series of letters) Pamela, and Henry Fielding’s Joseph Andrews and Tom Jones. The novel continued to develop into a major literary form of the 19th century.

Diarists

Just as many people in the 21st century record the details of their daily lives on Facebook or Twitter, people in the 18th century recorded their lives in diaries, works which now provide information and insight into the events of that time period. Some of the more well-known diarists were Samuel Pepys, John Evelyn, Daniel DeFoe, and Celia Fiennes.

Pepys provides detailed descriptions of London during the plague and the fire as well as daily life in the Restoration era.

Covering a much longer period of time, John Evelyn writes a more formal diary from the perspective of a conservative supporter of the monarchy and of the Church of England.

Although actually a fictional account of the plague, Daniel DeFoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year parallels Pepys’s accounts of the plague while giving even more detail. DeFoe’s A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain describes several journeys DeFoe made early in his life, providing a comprehensive picture of pre-Industrial Revolution England.

In a similar fashion but a much more daring endeavor, Celia Fiennes, the daughter and granddaughter of Puritan supporters, wrote what is perhaps the most unusual and interesting of the 18th century diaries. Not published until 1888, her journals document trips she made through every county in England as well as into parts of Scotland and Wales. Riding side saddle, Fiennes traveled most of the time with only one or two servants as companions. For a woman to travel without a father or husband as escort was extraordinary in this time period and dangerous as well. Fiennes records encounters with highwaymen and falls from her horse as she forded rivers and traveled England’s rough roads. Ostensibly traveling for her health, Fiennes observed local industries and described the landscape, both natural and manmade. Her family’s Puritan views are apparent in her comments about the churches, clergymen, and local religious conventions.

Key Takeaways

- The Great Fire of London in 1666 and another outbreak of the plague affected the literature produced in the Restoration and 18th century.

- Neoclassicism, a facet of the Enlightenment era, produced highly structured, formal literature modeled on classical Greek and Roman literature.

- During the 18th century, the English language became more standardized and prescriptive.

- The first English dictionaries, particularly Dr. Samuel Johnson’s dictionary, were produced during the 18th century.

- The Restoration brought about the re-opening of the theatres and the development of new drama, including the comedy of manners.

- The novel had its origins in the 18th century.

- Journals and diaries were an important form of literature in the Restoration and 18th century.

Resources

Background

The Monarchy

- “1660–1685: Restoration of Stuart Dynasty & Reign of Charles II.” Alok Yadav. George Mason University.

- “Charles II of England (1630–1685).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt. from Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed. Vol XV. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. 142.

- “English Civil War: The Glorious Revolution.” E.L. Skip Knox. Boise State University.

- “The Forgotten Tricentennial: England’s Glorious Revolution.” Donald E. Wilkes, Jr., Professor of Law, University of Georgia School of Law. Feb. 14, 1989.

- “The Glorious Revolution.” David Cody, Hartwick College. The Victorian Web.

- “James II of England (1633–1701).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt. from Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed. Vol XV. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. 142.

- William III and Mary II (1689–1702 AD). Britannia.com.

The Plague

- “The Great Plague of 1665.” Alok Yadav. George Mason University.

- “The Great Plague of 1665–6.” Education. The National Archives.

- “The Great Plague of London, 1665.” Contagion: Historic Views of Diseases and Epidemics. Harvard University Library Open Collections Program.

- “The Plague Book.” Historical Collections at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library. University of Virginia. digital images of a 16th-century plague book.

The Great Fire of London

- “The Great Fire of London, 1666.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Great Fire of London: Skyline Animation.” BBC History. BBC.

- “London’s Burning: The Great Fire of London 1666.” Museum of London.

The Enlightenment

British Museum Series of Online Tours on the Enlightenment

The Enlightenment

- “Age of the Enlightenment.” Gerhard Rempel. Western New England College.

- “The Enlightenment.” Prof. Norman West. Suffolk Community College.

- “The European Enlightenment: The Eighteenth Century.” Richard Hooker. 1996. World Civilizations: An Internet Classroom and Anthology. Washington State University.

- “The European Enlightenment: The Scientific Revolution.” Richard Hooker. 1996. World Civilizations: An Internet Classroom and Anthology. Washington State University.

- “Introduction to Neoclassicism.” Lelia Melani. Brooklyn College. City University of New York.

- “The Neoclassic Age.” Sarah E. Selby. Waycross College.

- “Neoclassicism: An Introduction.” The Victorian Web.

- “Sir Christopher Wren (1632–1723).” Historic Figures. BBC History. BBC.

Language

- “1755—Johnson’s Dictionary.” Learning: Dictionaries and Meanings. British Library.

- “The Age of Dictionaries.” Learning: Changing Language. British Library.

- “The English Language in the 18th Century.” Katya Gifford. Humanities Web.

- “Johnson’s Dictionary.” Clark Library. University of California, Los Angeles.

- “Johnson’s Dictionary.” Learning: Changing Language. British Library.

- “The King’s English: Eighteenth-Century Language.” Education. Colonial Williamsburg. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- “Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary: Sources and Editions.” Vassar College Libraries. Archives and Special Collections.

Restoration Drama

- “Aphra Behn (1640–1689). Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Restoration Drama.” TheatreHistory.com. rpt. from Martha Fletcher Bellinger. A Short History of the Theatre. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1927. 249–59.

- “The Restoration Drama.” Theatre Database. rpt. from William Vaughn Moody and Robert Morss Lovett. A History of English Literature. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1902.

- “Types of Comedy.” Folger Shakespeare Library.

- “Women in the Theater After the Restoration.” Ruth Nestvold. The Aphra Behn Page.

The Novel

- “The History of the Novel.” Dr. Agatha Taormina. Northern Virginia Community College.

- “The Novel.” Lelia Melani. Brooklyn College. City University of New York.

Diarists

- “Diaries of the Seventeenth Century.” Mark Knights. Feb. 17 2011. BBC History.

Samuel Pepys

- The Diary of Samuel Pepys. Phil Gyford. daily entries from Pepys’s diaries and a subject index.

- The Diary of Samuel Pepys by Samuel Pepys. Project Gutenberg.

- “Sex, Lice and Chamber Pots in Pepys’ London.” Liza Picard. 17 Feb. 2011.BBC History. BBC.

- “Samuel Pepys (1633–1703).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

Daniel DeFoe

- A Journal of the Plague Year, written by a citizen who continued all the while. Project Gutenberg.

- “Voyage Narratives.” Daniel DeFoe. The Collection of the Lilly Library. Indiana University, Bloomington.

John Evelyn

- “The Diary of John Evelyn.” Internet Archive. California Digital Library.

- “John Evelyn: On Restoration and Revolution.” John Halsall. Internet Modern History Sourcebook.

Celia Fiennes

- “Celia Fiennes: Through England on a Side Saddle in the Time of William and Mary.” A Vision of Britain Through Time. University of Portsmouth.

- “Through England on a Side Saddle in the Time of William and Mary Being the Diary of Celia Fiennes.” A Celebration of Women Writers. University of Pennsylvania Libraries.

5.2 Jonathan Swift (1667–1745)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Define satire and apply the definition to Swift’s “A Modest Proposal.”

- Trace the historical events that led to the writing of “A Modest Proposal.”

- Evaluate Swift’s use of satire in “A Modest Proposal.”

Biography

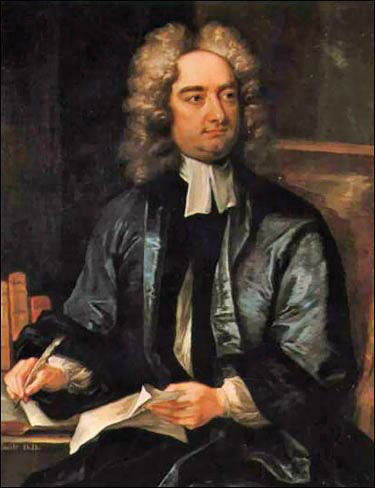

Jonathan Swift was born in Ireland of an Irish father and an English mother and felt the pull between the two countries all his life. He went to England to live for short periods on several occasions. After he became a clergyman he hoped to obtain a position in the Church of England. However, he was appointed to St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin, Ireland, a position with which he was deeply disappointed, even after becoming the Dean of St. Patrick’s.

Swift maintained friendships with other 18th-century writers such as Alexander Pope, William Congreve, John Gay, and John Arbuthnot. In fact, Pope was instrumental in helping Swift publish what is probably his most well-known work, Gulliver’s Travels.

St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, Ireland.

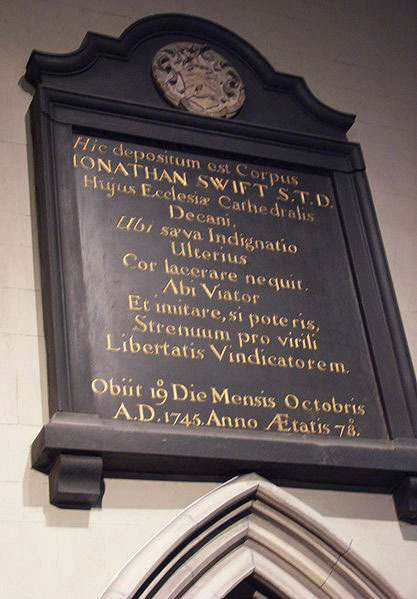

Commemorative plaque to Swift in the cathedral.

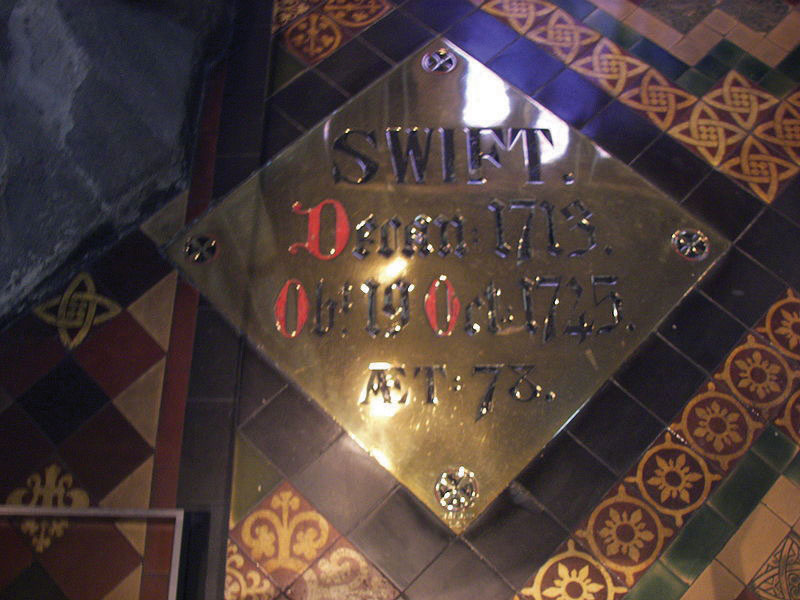

Swift’s gravesite in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin.

Bust of Swift in the cathedral.

Satire

Satirea literary manner, used in any genre, that blends criticism of a person, event, or situation with witty humor for the purpose of improving the object of the satire is a literary manner, used in any genre, that blends criticism of a person, event, or situation with witty humor for the purpose of improving the object of the satire. Writers such as Swift and Pope found much in their society that needed improvement, and satire was their weapon of choice.

Through witty, mocking making fun of problems in society, satirists hoped to draw attention to their targets so that the situations will be corrected. Some satire, such as that of Pope’s “The Rape of the Lock,” is gentle and humorous (Horatian satire); other satirical works, such as Swift’s “A Modest Proposal,” are harsh and vindictive (Juvenalian satire).

“A Modest Proposal”

As Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin, Ireland, Jonathan Swift observed the poverty and oppression of the Irish people and proposed remedies for the problems. He wrote many pamphlets outlining serious solutions to the problems of wide-spread poverty in Ireland, problems that were beyond the control of the poor lower classes. Crop failures resulted in very little available food, and what was available was extremely expensive. The British government imposed impossibly high taxes specifically to force small farmers to sell their land and work as tenant farmers for the wealthy Irish landowners who kept them in poverty. There were well-known instances of corruption in the governing of Ireland. In one example, government officials took bribes to allow certain people to print coins until the economy was flooded with money. Those of you who know anything about economics know that the result was rampant inflation.

Swift tried hard to help the Irish poor by proposing and pushing for reforms. For his efforts he was considered an enemy of the British government and of the Irish aristocracy, and warrants were issued for his arrest. On several occasions, the poor Irish, who knew he was trying to help them, hid him from soldiers sent to arrest him.

After writing a number of proposals which were ignored, Swift turned to satire in an effort to shock his audience into paying attention to the problem he addressed. He was so disgusted with the ruling upper classes who refused to consider any of his serious proposals that he wrote his “Modest Proposal,” a work designed to be so outrageous that it would shock his audience into action. Swift, in essence, is saying, “What you’re doing to the Irish is just as cruel as if you were to eat the children,” the implication of his line that they have already “devoured” the parents so they might as well eat the children.

In writing “A Modest Proposal,” Swift drew on his suspicious attitude about modern science to couch his proposal in terms of a “scientific” study. Writing in the Age of Reason, when science and rational thought dominated sentimental feeling, Swift creates a fictional persona, the projector, who is the “speaker”/writer of “A Modest Proposal.” The projector is a logistician, the kind of scientifically minded person who might belong to the recently formed Royal Society, a prestigious organization dedicated to the conducting of and writing about empirical study.

Swift achieves two purposes in creating the projector persona. First, science becomes an object of satire. The projector’s “modest proposal” proves to be so outrageous that no rational, enlightened person could possibly consider it. Second, following the publication of his Drapier’s letters, pamphlets urging political solutions to the problems that had resulted in extreme poverty among Ireland’s poor, the British government issued a warrant for Swift’s arrest. Although the essay was published anonymously, its writer’s identity was widely known. Still, the use of the projector as the writer of the piece provided a modicum of protection for its author.

Key Takeaways

- Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” exemplifies Juvenalian satire.

- Swift turned to satire after serious proposals failed to effect any changes in the Irish economic situation.

- “A Modest Proposal” evinces tenets of neoclassicism in its use of Juvenalian satire and in its Aristotelian persuasive structure.

Exercises

- Why is the title “A Modest Proposal” ironic?

- Read paragraph 12 of “A Modest Proposal”: “I grant this food will be somewhat dear, and therefore very proper for landlords, who, as they have already devoured most of the parents, seem to have the best title to the children.” At this point, as well as in other similar passages, Swift drops the mask of satire and speaks with invective (abusive, insulting language that is characteristic of Juvenalian satire). What he proposes is simply making this figurative sentence literal. In what sense have the landlords “devoured” the parents?

-

In paragraph 4, Swift uses the phrase “a child just dropped from its dam” and the word “breeders” to refer to the women who bear children. What purpose does this diction serve?

(Note: “Dropped from its dam” is diction used in reference to livestock, particularly horses. A foal is said to be “dropped from its dam,” the dam being the mare.)

-

Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” is often anthologized as an example of a persuasive essay. Analyze the essay’s classical argumentative structure.

- How and why does the projector use emotional appeal in his opening paragraph?

- In what paragraph does the projector present his thesis? Why does he use a delayed thesis structure rather than giving the thesis in the opening paragraph?

- What logical appeal does the projector offer to support his thesis? How does he use statistics?

- Later in the essay, the projector presents a list of logical reasons to convince his audience to accept his proposal. List the reasons. Are they convincing?

- The projector addresses possible objections—what possible counter-arguments does he anticipate?

- Who is the intended audience for the projector’s proposal?

Resources

Biography

- “Jonathan Swift: A Brief Biography.” David Cody. Hartwick College. The Victorian Web.

- “The Life of Jonathan Swift (1667–1745).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

Text of “A Modest Proposal”

- “A Modest Proposal.” Project Gutenberg.

- “A Modest Proposal.” The Victorian Web.

- “Jonathan Swift: A Modest Proposal. (1729).” Renascence Editions. University of Oregon.

Audio

- “A Modest Proposal.” LibriVox.

- “A Modest Proposal.” Project Gutenberg.

- “Swift’s A Modest Proposal.” In Our Time. BBC Radio 4. audio of discussion of “A Modest Proposal.”

Scriblerus Club

- “Scriblerus Club.” Valerie Rumbold. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- “The Scriblerus Club.” In Our Time. BBC Radio 4. audio of discussion of the Scriblerus Club.

Swift and Science

- “Swift’s Attitude Toward Science and Technology.” David Cody. Hartwick College. The Victorian Web.

- “History.” The Royal Society.

- “Women and Science.” Folger Shakespeare Library. video.

5.3 Alexander Pope (1688–1744)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Define satire and apply the definition to Pope’s “The Rape of the Lock.”

- Trace the historical events that led to the writing of “The Rape of the Lock.”

- Evaluate Pope’s use of satire in “The Rape of the Lock.”

After the Great Fire of London aroused anti-Catholic feeling that had simmered since the reign of James II, Parliament passed the first of two Test Acts, laws that banned Roman Catholics and nonconformists (Protestants not members of the Church of England, such as Puritans) from holding public office, serving in the military, attending universities, or essentially having any part in public life. Born into a Roman Catholic family, Alexander Pope’s education was limited to occasional tutoring from priests and his own regimen of study. Pope suffered from what many experts now believe to be tuberculosis of the bone, resulting in a deformity in his back and stunted growth. Both his religion and his physical disabilities barred him from the kind of participation in court life that resulted in patronage that other poets enjoyed. With his family’s financial security from his father’s business, Pope was able to devote enough time to his writing, translating, and editing to begin earning a comfortable living. He soon established himself as one of the prominent neoclassic writers.

Portrait by Jean-Baptiste van Loo.

Text

- “The Rape of the Lock.” Electronic Classics Series. Jim Manis, Senior Faculty Editor. Pennsylvania State University.

- “The Rape of the Lock.” S. Constantine. University of Massachusetts. with annotations.

- “The Rape of the Lock and Other Poems by Alexander Pope.” Project Gutenberg.

- “The Rape of the Lock by Alexander Pope.” Edited by Jack Lynch. Rutgers University.

- “Selected Poetry of Alexander Pope.” Representative Poetry Online. University of Toronto.

“The Rape of the Lock”

Like Swift, Alexander Pope chose satire as his method for addressing and possibly correcting a difficult situation. Unlike Swift, Pope addresses a personal situation.

Within the society of aristocratic Roman Catholic families, a young gentleman, Lord Petre, furtively cut a lock of hair from a beautiful young woman he was courting, Arabella Fermor. Arabella and her family were incensed at the “assault” and refused to associate with Lord Petre and his family, causing a rift within the social circle of Catholic families. A mutual friend John Caryll suggested that Pope write a humorous poem that might encourage the families to take the situation less seriously and to reconcile.

Heroic Couplet

A heroic couplettwo lines of poetry in iambic pentameter that rhyme is two lines of poetry in iambic pentameter that rhyme. Neoclassical writers favored this structured, symmetrical verse form. Pope uses the highly complex closed heroic coupleta rigidly structured verse form consisting of two lines, each iambic pentameter, which rhyme and which form a complete thought, a rigidly structured verse form consisting of two lines, each iambic pentameter, which rhyme and which form a complete thought.

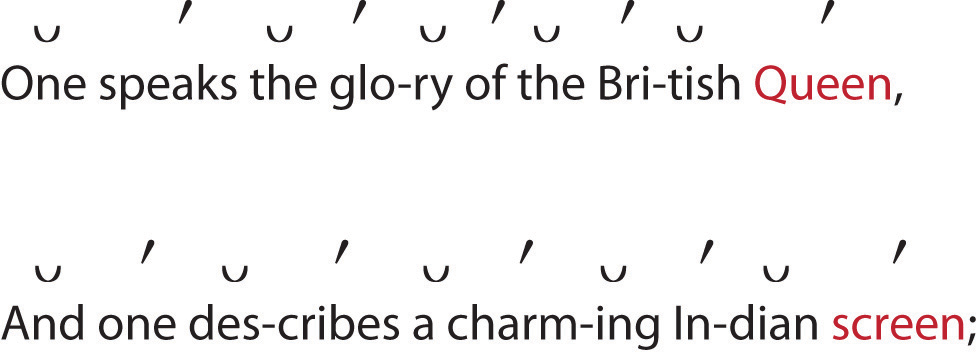

Figure 5.4

These two lines in Figure 5.4 are from Canto 3, lines 13–14. Note that each line is iambic pentameter, the two lines rhyme, and the semi-colon (end punctuation) indicates a complete thought.

Mock Epic

“The Rape of the Lock” is a mock epica poem which uses the characteristics and conventions of an epic but for a humorous and satirical purpose rather than a serious purpose, a poem which uses the characteristics and conventions of an epic but for a humorous and satirical purpose rather than a serious purpose. Even the title ironically suggests a serious crime when the offense is actually cutting a lock of hair.

- An epic states the theme at the beginning of the poem. The first two lines of Canto 1 follow the convention: “What dire offense from amorous causes springs, / What mighty contests rise from trivial things, / I sing.…” The word trivial epitomizes the theme, and the theme in turn leads to the choice of form, the mock epic which treats a trivial subject as if it were of epic importance. In contrast to the epic Paradise Lost, in which the theme is nothing less than the creation and fall of the human race, Pope’s mock epic highlights human superficiality and vanity.

- An epic invokes a muse: Pope’s muse is not a Greek god or the Holy Spirit, Milton’s muse; his muse is another human, John Caryll who asked him to write the poem.

- The supernatural forces are not God, angels, and demons of Paradise Lost but the sylphs whose duties are to guard Belinda’s hair and jewelry.

- The epic battles are reduced to card games. The preparation for battle takes place at Belinda’s dressing table and is presented in diction suggestive of religious rites (see Canto 1 lines 121–148). The Baron also prepares for battle by praying at his altar to love (see Canto 2 lines 35–46).

- The valiant feats of courage become clipping a lock of hair, threatening the Baron with a hairpin, and making him sneeze with a pinch of snuff.

Another technique Pope employs to convey his satirical point is the literary device called zeugmathe use of a word to apply to two disparate situations, the use of a word to apply to two disparate situations. For example, Canto 2, lines 105–110 present serious tragedies the sylphs fear might happen to Belinda juxtaposed with trivial possibilities:

Sidebar 5.2.

Whether the nymph shall break Diana’s law,

Or some frail china jar receive a flaw,

Or stain her honor, or her new brocade

Forget her prayers, or miss a masquerade.…

Belinda’s losing her virtue becomes the equivalent of an ornamental jar being cracked. Staining her honor becomes the equivalent of staining her dress. The effect is to emphasize the triviality of aristocratic values, a world in which marring one’s appearance by losing a single lock of hair is considered as consequential as a rape.

Key Takeaways

- Alexander Pope’s “The Rape of the Lock” exemplifies Horatian satire.

- “The Rape of the Lock” is a mock epic.

- “The Rape of the Lock” is written in closed heroic couplets, a verse form that embodies the structure and symmetry admired by neoclassicists.

Exercises

- Review the list of epic characteristics and conventions in the information about Milton’s Paradise Lost. In addition to the examples given, identify instances in “The Rape of the Lock” in which Pope trivializes epic conventions to create a mock epic.

- Describe Belinda and the Baron in Pope’s “The Rape of the Lock.”

- What are the objects of satire in “The Rape of the Lock”?

- In what ways could Pope’s work be characterized as Horatian satire in contrast with Swift’s Juvenalian satire?

- What parallels do you find in Milton’s epic Paradise Lost and Pope’s mock epic?

- Pope writes about aristocratic society in “The Rape of the Lock.” How would you compare/contrast the families involved in this situation with the aristocratic British and Irish people Swift alludes to in “A Modest Proposal”?

Resources

Biography

- “Alexander Pope (1688–1744).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt from Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed., Vol. XXII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. 87.

- “Alexander Pope.” Academy of American Poets. Poets.org.

- “Alexander Pope.” The Twickenham Museum.

Text

- “The Rape of the Lock.” Electronic Classics Series. Jim Manis, Senior Faculty Editor. Pennsylvania State University.

- “The Rape of the Lock.” S. Constantine. University of Massachusetts. with annotations.

- “The Rape of the Lock and Other Poems by Alexander Pope.” Project Gutenberg.

- “The Rape of the Lock by Alexander Pope.” Edited by Jack Lynch. Rutgers University.

- “Selected Poetry of Alexander Pope.” Representative Poetry Online. University of Toronto.

Background Information

- “Alexander Pope’s Rape of the Lock: An Introduction.” David Cody. Hartwick College. The Victorian Web.

- “The Story Behind the Poem.” The Rape of the Lock Homepage. S. Constantine. University of Massachusetts.

Heroic Couplet

- “The Heroic Couplet: Its Rhyme and Reason.” J. Paul Hunter. University of Chicago. Lecture presented at the National Humanities Center.

- “Heroic Couplet.” The UVic Writer’s Guide. Department of English. University of Victoria.

- “Heroic Couplets.” Jack Lynch. Glossary of Literary and Rhetorical Terms. Rutgers University.

- “Heroic Couplets.” Erik Simpson. Connections: A Hypertext Resource for Literature. Grinnell College.

Mock Epic

- “High Burlesque: Mock Epic (Mock Heroic); Parody.” The UVic Writer’s Guide. Department of English. University of Victoria.

- “Zeugma.” The UVic Writer’s Guide. Department of English. University of Victoria.

- “Zeugma.” Literary Terms and Definitions. Dr. L. Kip Wheeler. Carson-Newman College.

5.4 Frances Burney [Madame D’Arblay] (1752–1840)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize how Frances Burney’s social status affected her opportunities to develop literary talents.

- Evaluate the literary merits of journals and diaries as well as their role in revealing life in previous time periods.

Biography

Early 20th-century writer Virginia Woolf referred to Frances (often known as Fanny) Burney as the “Mother of English Fiction.” Born into a family of musicians, Burney had little formal education but learned and loved to read and write. Like many early women writers, Burney published her first novel Evelina anonymously, and it met with great success.

Portrait by Edward Francesco Burney.

From her youth, Burney kept a diary and her name figures prominently among the other great diarists of the 18th century such as Pepys, DeFoe, and Fiennes. One of the most chilling passages of any of the diaries is Burney’s account of undergoing a mastectomy without anesthesia in her home. Amazingly, she recovered from the surgery, but she could not bring herself to write about the agonizing ordeal until nine years later when she described it in a letter to her sister.

Text

The following excerpt from an early letter to her father describes her first scheduled meeting with Queen Charlotte, wife of King George III, after Burney, through the influence of a friend, had been appointed to the position of Second Keeper of the Robes.

Sidebar 5.3.

“I do beg of you,” said dear Mrs. Delany, “When the queen or the king speak to you, not to answer with mere monosyllables. The queen often complains to me of the difficulty with which she can get any conversation, as she not only always has to start the subjects, but, commonly, entirely to support them: and she says there is nothing she so much loves as conversation, and nothing she finds so hard to get. She is always best pleased to have the answers that are made her lead on to further discourse. Now, as I know she wishes to be acquainted with you, and converse with you, I do really entreat you not to draw back from her, nor to stop conversation with only answering ‘Yes,’ or ‘No.’”

This was a most tremendous injunction; however, I could not but promise her I would do the best I could.

To this, nevertheless, she readily agreed, that if upon entering the room, they should take no notice of me, I might quietly retire. And that, believe me, will not be very slowly! They cannot find me in this house without knowing who I am, and therefore they can be at no loss whether to speak to me or not, from incertitude.

A PANIC.

In the midst of all this, the queen came!

I heard the thunder at the door, and, panic struck, away flew all my resolutions and agreements, and away after them flew I!

Don’t be angry, my dear father—I would have stayed if I could, and I meant to stay—but, when the moment came, neither my preparations nor intentions availed, and I arrived at my own room, ere I well knew I had left the drawing-room, and quite breathless between the race I ran with Miss Port and the joy of escaping,

from The Diary and Letters of Madame D’Arblay—Volume 1

Queen Charlotte, Consort of King George III by Benjamin West.

Key Takeaways

- Frances Burney exemplifies and records the life of an aristocratic woman in the 18th century.

- Burney is one of several notable diarists from the 18th century.

Exercises

- How would you describe the young woman Frances Burney based only on this excerpt?

- What does this excerpt reveal about the system of social classes in late 18th-century Britain?

- Why does Burney react the way she does?

- Why does Burney feel the need to apologize to her father for her behavior?

Resources

Texts

- The Diary and Letters of Madame D’Arblay—Volume 1 by Fanny Burney. Project Gutenberg.

- The Diary and Letters of Madame D’Arblay—Volume 2 by Fanny Burney. Project Gutenberg.

- The Diary and Letters of Madame D’Arblay—Volume 3 by Fanny Burney. Project Gutenberg.

- Evelina: Or The History of A Young Lady’s Entrance into the World. London: T. Lowndes, 1778; Reprinted New York: W. W. Norton & Company (Norton Library Edition), 1965. rpt. in A Celebration of Women Writers. University of Pennsylvania Libraries.

- Evelina, Or, the History of a Young Lady’s Entrance into the World by Fanny Burney. Project Gutenberg.

Biography

- “Engines of Our Ingenuity: Fanny Burney.” John H. Lienhard. University of Houston. text and audio.

- “Frances Burney (1752–1840).” Valerie Patten. Library and Early Women’s Writing: Women Writers. Chawton House Library.

5.5 Samuel Johnson (1709–1784)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify the various literary roles and the prominent place Samuel Johnson held in 18th-century literary society.

- Interpret Johnson’s “The Vanity of Human Wishes” as a criticism of 18th-century society.

Biography

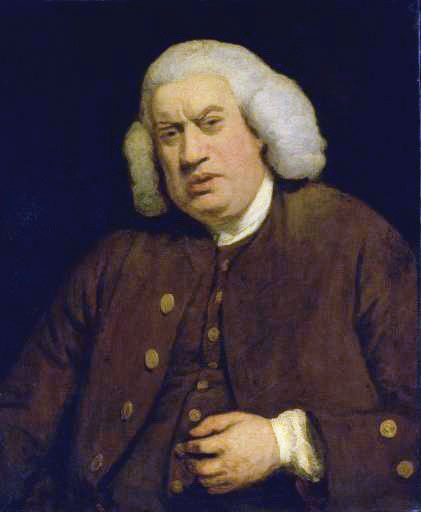

Primarily known during his lifetime as a lexicographer and a journalist, Samuel Johnson was also a poet and a leading figure in late 18th-century literary circles. The son of a bookseller, Johnson lacked the funds to complete his degree at Oxford. However, he read voraciously at home and began his college career at Oxford by impressing his teachers and fellow students with his knowledge. After establishing himself as a journalist, Johnson was hired to compile a dictionary which became one of the most well-known of English dictionaries.

Portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

“The Vanity of Human Wishes”

Text

- Dr. Johnson’s Works: Life, Poems, and Tales, Volume 1 by Samuel Johnson. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” Facsimile of the 1749 edition by Jack Lynch. Rutgers University.

- “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” Renascence Editions. R. S. Bear. University of Oregon.

- “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English. University of Toronto.

Johnson’s “The Vanity of Human Wishes” employs many of the characteristics of neoclassical poetry: it is patterned after the classical Latin works of Juvenal; it uses the formal, highly structured closed heroic couplet; it exalts reason; it uses personificationgiving human characteristics to inanimate objects or abstract qualities [giving human characteristics to inanimate objects or abstract qualities].

The first stanza presents the main idea of the poem: that life is like a maze which each individual stumbles through without a guide. The poem is then developed like an essay: each “vain wish” serves as a topic sentence developing the thesis. Each topic sentence is, in turn, developed with specific examples. This poem is often difficult for modern readers because many of the examples are allusions to people, places, and events familiar to the 18th century audience but not to a current audience. However, the main ideas—the vain wishes—are equally relevant.

The copy of the poem from Representative Poetry Online provides notes which explain many of the unfamiliar references.

Key Takeaways

- A key figure in the 18th-century literary world, Samuel Johnson was a lexicographer, journalist, poet, diarist, essayist, dramatist, and writer of short fiction.

- Johnson’s work exemplifies the characteristics of neoclassicism.

Resources

General Resources

- “Samuel Johnson: A Tricentennial of Johnson’s Birth.” Clark Library. University of California, Los Angeles.

- “Samuel Johnson’s ‘The Vanity of Human Wishes.’” The Victorian Web. George P. Landow. Brown University.

Biography

- “Samuel Johnson (1709–1784).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt. from Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed., Vol. XV. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. 471–2.

- “Samuel Johnson (1709–1784).” Historic Figures. BBC History.

- “Samuel Johnson: An Introduction.” The Victorian Web. David Cody. Hartwick College.

Text “The Vanity of Human Wishes”

- Dr. Johnson’s Works: Life, Poems, and Tales, Volume 1 by Samuel Johnson. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” Facsimile of the 1749 edition by Jack Lynch. Rutgers University.

- “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” Renascence Editions. R. S. Bear. University of Oregon.

- “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English. University of Toronto.

Audio

- “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” The PennSound Anthology of Restoration and 18th-Century Verse. edited and performed by John Richetti. PennSound Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing.

Daisy

- “The Vanity of Human Wishes.” Internet Archive.

5.6 Thomas Gray (1716–1771)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objective

- Assess the characteristics of Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” that anticipate the Romantic movement.

Biography

Although Thomas Gray had a troubled and less than prosperous childhood—his mother, a milliner, left his father because of abuse—Gray obtained an excellent education at Eton and at Cambridge, largely because of his uncle who was an assistant master at Eton. While at Eton he made friends with young men who were sons of prominent families and who would become prominent themselves. Financed possibly by his father and possibly by his wealthy friends and their families, Gray toured continental Europe and then returned to continue studying independently at Cambridge. Gray lived for a time with his mother in the village of Stoke Poges, and it is believed that he wrote his “Elegy” in the parish churchyard there. He is buried next to the small church with his mother and aunt. At the churchyard in Stoke Poges, a monument has been erected to Gray, whose tomb is also there.

Gray’s monument near the Stoke Poges churchyard.

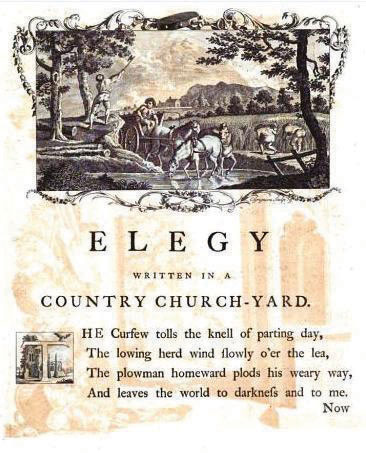

“Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”

Although Gray was not a prolific poet, his “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” is one of the most well-known and popular poems in the English language. An elegya lament for the dead is a lament for the dead, usually a specific person as in Milton’s elegy Lycidas written to mourn his friend Edward King. Gray’s “Elegy” is more a lament for an entire group of people—the common people of a typical village in England who live simple lives away from the public eye.

Gray is considered part of a group of poets from the late 18th century known as the graveyard schoolpoets who wrote melancholy, meditative poetry about death, poets who wrote melancholy, meditative poetry about death. As part of the graveyard school, Gray writes a melancholy lament for the ordinary people who lie buried in this tiny, obscure location. Stanzas 8, 9, and 14 are well-known stanzas that convey this theme.

Gray’s “Elegy” also is an example of topographical poetrypoetry inspired by a geographical setting—poetry inspired by a geographical setting. British churchyards were typically graveyards, Christians at that time believing they should be buried in hallowed ground. The poem begins with a description of the location, the narrator noting specific details that allow the reader to imagine the scene and at the same time establishing the melancholy mood.

Because of these characteristics, Gray’s “Elegy” is important as a precursor of the Romantic movement which began in the late 18th century. Neoclassical poetry emphasized symmetry, reason, and rational thought—the life of the mind. Gray’s poem marks the beginning of a trend to emphasize organic form, sentiment, and emotion—the life of the heart. The Elegy’s description of nature, its sensitivity to emotion rather than emphasis on reason, and its elevation of common people all intimate important characteristics of 19th century Romanticism.

Text

Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard

The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,

The lowing herd winds slowly o’er the lea,

The ploughman homeward plods his weary way,

And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

Now fades the glimmering landscape on the sight,

And all the air a solemn stillness holds,

Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight,

And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds:

Save that from yonder ivy-mantled tower

The moping owl does to the moon complain

Of such as, wandering near her secret bower,

Molest her ancient solitary reign.

Beneath those rugged elms, that yew-tree’s shade,

Where heaves the turf in many a mouldering heap,

Each in his narrow cell for ever laid,

The rude Forefathers of the hamlet sleep.

The breezy call of incense-breathing morn,

The swallow twittering from the straw-built shed,

The cock’s shrill clarion, or the echoing horn,

No more shall rouse them from their lowly bed.

For them no more the blazing hearth shall burn,

Or busy housewife ply her evening care:

No children run to lisp their sire’s return,

Or climb his knees the envied kiss to share,

Oft did the harvest to their sickle yield,

Their furrow oft the stubborn glebe has broke;

How jocund did they drive their team afield!

How bow’d the woods beneath their sturdy stroke!

Let not Ambition mock their useful toil,

Their homely joys, and destiny obscure;

Nor Grandeur hear with a disdainful smile

The short and simple annals of the Poor.

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e’er gave,

Awaits alike th’ inevitable hour:—

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

Nor you, ye Proud, impute to these the fault

If Memory o’er their tomb no trophies raise,

Where through the long-drawn aisle and fretted vault

The pealing anthem swells the note of praise.

Can storied urn or animated bust

Back to its mansion call the fleeting breath?

Can Honour’s voice provoke the silent dust,

Or Flattery soothe the dull cold ear of Death?

Perhaps in this neglected spot is laid

Some heart once pregnant with celestial fire;

Hands, that the rod of empire might have sway’d,

Or waked to ecstasy the living lyre:

But Knowledge to their eyes her ample page,

Rich with the spoils of time, did ne’er unroll;

Chill Penury repress’d their noble rage,

And froze the genial current of the soul.

Full many a gem of purest ray serene

The dark unfathom’d caves of ocean bear:

Full many a flower is born to blush unseen,

And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

Some village-Hampden, that with dauntless breast

The little tyrant of his fields withstood,

Some mute inglorious Milton here may rest,

Some Cromwell, guiltless of his country’s blood.

Th’ applause of list’ning senates to command,

The threats of pain and ruin to despise,

To scatter plenty o’er a smiling land,

And read their history in a nation’s eyes,

Their lot forbad: nor circumscribed alone

Their growing virtues, but their crimes confined;

Forbad to wade through slaughter to a throne,

And shut the gates of mercy on mankind,

The struggling pangs of conscious truth to hide,

To quench the blushes of ingenuous shame,

Or heap the shrine of Luxury and Pride

With incense kindled at the Muse’s flame.

Far from the madding crowd’s ignoble strife,

Their sober wishes never learn’d to stray;

Along the cool sequester’d vale of life

They kept the noiseless tenour of their way.

Yet e’en these bones from insult to protect

Some frail memorial still erected nigh,

With uncouth rhymes and shapeless sculpture deck’d,

Implores the passing tribute of a sigh.

Their name, their years, spelt by th’ unletter’d Muse,

The place of fame and elegy supply:

And many a holy text around she strews,

That teach the rustic moralist to die.

For who, to dumb forgetfulness a prey,

This pleasing anxious being e’er resign’d,

Left the warm precincts of the cheerful day,

Nor cast one longing lingering look behind?

On some fond breast the parting soul relies,

Some pious drops the closing eye requires;

E’en from the tomb the voice of Nature cries,

E’en in our ashes live their wonted fires.

For thee, who, mindful of th’ unhonour’d dead,

Dost in these lines their artless tale relate;

If chance, by lonely contemplation led,

Some kindred spirit shall inquire thy fate,—

Haply some hoary-headed swain may say,

Oft have we seen him at the peep of dawn

Brushing with hasty steps the dews away,

To meet the sun upon the upland lawn;

‘There at the foot of yonder nodding beech

That wreathes its old fantastic roots so high.

His listless length at noontide would he stretch,

And pore upon the brook that babbles by.

‘Hard by yon wood, now smiling as in scorn,

Muttering his wayward fancies he would rove;

Now drooping, woeful wan, like one forlorn,

Or crazed with care, or cross’d in hopeless love.

‘One morn I miss’d him on the custom’d hill,

Along the heath, and near his favourite tree;

Another came; nor yet beside the rill,

Nor up the lawn, nor at the wood was he;

‘The next with dirges due in sad array

Slow through the church-way path we saw him borne,—

Approach and read (for thou canst read) the lay

Graved on the stone beneath yon aged thorn.’

The Epitaph

Here rests his head upon the lap of Earth

A youth to Fortune and to Fame unknown.

Fair Science frowned not on his humble birth,

And Melacholy marked him for her own.

Large was his bounty, and his soul sincere,

Heaven did a recompense as largely send:

He gave to Misery all he had, a tear,

He gained from Heaven (‘twas all he wish’d) a friend.

No farther seek his merits to disclose,

Or draw his frailties from their dread abode

(There they alike in trembling hope repose),

The bosom of his Father and his God.

Key Takeaways

- Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” is one of the more well-known and popular poems in British literature.

- Features of “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” such as description of nature, its sensitivity to emotion rather than emphasis on reason, and its elevation of common people make the poem a bridge between neoclassical and Romantic poetry.

Exercises

- In the first line, what connotations do the words curfew, toll, and knell convey?

- In the first four stanzas, what descriptions of the natural world add to the melancholy mood of the poem?

- In stanza 4, to whom does the phrase “the rude forefathers” refer?

- In stanzas 5, 6, and 7, the narrator ponders the simple pleasures that the “rude forefathers” no longer enjoy. What pleasures does he name? How do these stanzas relate to the poem’s theme?

- Paraphrase stanzas 8, 9, and 10. To whom does the narrator address these stanzas?

- The next section of the poem explains that the people born into this obscure village may have had the same natural intelligence, talent, and ability of people who became famous. What prevented the villagers from achieving fame? What advantages came from their failure to achieve prominence?

- In the last 6 stanzas before The Epitaph, what does the narrator imagine happening?

- Many critics have conjectured about the purpose of The Epitaph. What is an epitaph? What do you think is the purpose of this epitaph?

Designs by Mr. R. Bentley for Six Poems by Mr. T. Gray. London: R Dodsley, 1775.

Resources

General Information

- The Thomas Gray Archive: A Collaborative Digital Collection. University of Oxford. primary text, criticism, biography, bibliography, glossary, concordance, images.

Biography

- “Biography.” The Thomas Gray Archive: A Collaborative Digital Collection. University of Oxford.

- “Thomas Gray.” Stoke Poges Parish Council.

- “Thomas Gray (1716–1771).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt. from Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed., Vol. XII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. 395.

Text

- “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard.” The Thomas Gray Archive: A Collaborative Digital Collection. University of Oxford. annotated text of the poem.

- “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English. University of Toronto.

- Select Poems of Thomas Gray by Thomas Gray. Project Gutenberg.

Audio

- “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard.” The PennSound Anthology of Restoration and 18th-Century Verse. edited and performed by John Richetti. PennSound Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing.

- “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard.” LibriVox.

Video

- Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.