This is “The Early 17th Century”, chapter 4 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 4 The Early 17th Century

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

4.1 The Early Seventeenth Century

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Comprehend the political and religious turmoil that influenced the literature of the early 17th century.

- Identify the contributions of Shakespeare and the King James Bible to early modern English, the language of the 17th century.

- Define and compare metaphysical poetry and cavalier poetry.

- Recognize the effects of the Puritan movement on drama and the theatre.

Political and Religious Controversy

In the sixteenth-century Tudor era, the religious turmoil that characterized the English Reformation under Henry VIII and continued, particularly during the reign of his daughter Queen Mary I, ameliorated during the reign of Elizabeth I. James I of England and VI of Scotland succeeded the childless Elizabeth, initiating the Stuart line of rulers. England’s religious struggles continued into the Stuart era, within forty years culminating in the English Civil War.

Only two years after James I came to the throne in 1603, Catholic activists attempted to assassinate him in what came to be known as the Gunpowder Plot. Barrels of gunpowder were planted underneath the Houses of Parliament and were set to be detonated while James I was present to open Parliament’s session. The goal was to kill the King and most if not all the Lords, thus throwing England into chaos and allowing an opportunity to establish a Catholic realm. However, the plan was discovered and the gun powder found, guarded by Guy Fawkes. The BBC presents a brief computer-generated video that portrays the history of the Gunpowder Plot.

Van Dyck’s portrait of Charles I.

When Charles I succeeded his father James I as king, he continued the objectionable policies of his father and, in fact, worsened the religious controversy by marrying a Roman Catholic French princess. Charles I himself favored the more formal services of the Anglican church angering those who wanted to “purify“ the Church of England. Thus he managed to alienate all religious factions—Catholic, Anglican, and Puritan.

The controversies that led to the English Civil War were both political and religious. In the political realm, James I and his successor Charles I insisted on the divine right of kings—the belief that kings were chosen by God and answered to no one but God, a theory that included the monarch’s right to rule without parliamentary intervention. On the religious front, in addition to the continuing strife between Protestant and Roman Catholic were added the additional demands of Protestant reformers who demanded reforms within the Church of England and the right to worship as dissenting organized religions. Against the monarch’s belief in the divine right of kings stood the growing conviction that Parliament should have greater influence on governmental decisions.

The Puritan Revolution (The English Civil War)

Member of Parliament Oliver Cromwell distinguished himself as a radical Puritan, organized and led a cavalry regiment of Parliament forces, and quickly rose to the leadership of the Puritan Revolution. Cromwell, a leading force in convincing Parliament to raise an army against the king, led the movement to execute Charles I.

Statue of Oliver Cromwell outside the British Houses of Parliament.

In 1649, Charles I was executed. Parliament’s House of Commons abolished the monarchy and the House of Lords, declaring England a Commonwealth. A few years later, Oliver Cromwell was named Lord Protector. The years between 1649 and 1660 were known as the Interregnum—literally meaning the time between kings. Upon Cromwell’s death, although Cromwell’s son assumed his father’s government position, the Commonwealth began to crumble under the son’s inept leadership. In 1660, Charles II, son of the executed king, assumed the throne and Britain’s monarchy was restored.

Language

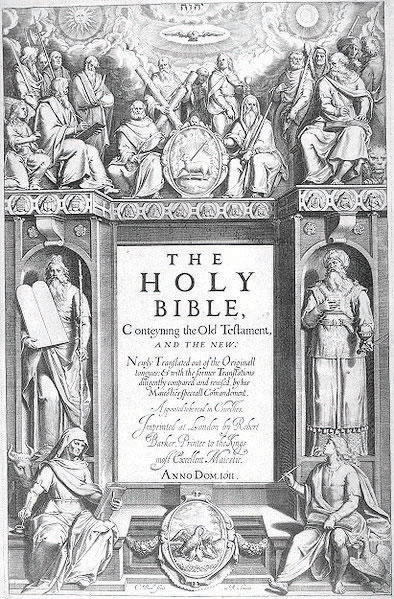

The early seventeenth century is considered the era of early modern English. Although contemporary audiences may consider the language of Shakespeare and the King James Bible quite different from 21st-century English, comparing the English of the seventeenth century with Chaucer’s Middle English reveals a vocabulary and a grammar familiar to contemporary readers. Both the works of Shakespeare and the publication of the King James Bible in 1611 helped standardize the language while at the same time enriching it with increased vocabulary and phrases now familiar to most English speakers. In her Words in English website, Suzanne Kemmer provides lists of words and phrases, now common in English, that originated with Shakespeare and the King James Bible. King James I authorized a committee of about 50 clergy/scholars to create a new English translation of the Bible, accessible to all lay people. The resulting translation was dedicated to King James I and is still commonly known by his name. The British Library presents a brief history of the King James Bible and digital images of a first edition. The Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text & Image, University of Pennsylvania Libraries provides an interactive digital version of a 1611 King James Bible.

Title page of 1611 King James Bible.

Literature

The Metaphysical Poets

Eighteenth-century writer Samuel Johnson first used the term metaphysical poets to refer to John Donne, Andrew Marvell, and other early 17th-century poets whose poetry was characterized by elaborate, unusual metaphors and philosophical speculations. The term metaphysicalideas beyond the physical; ideas that pertain to a world beyond the natural world refers to ideas beyond the physical, to ideas that pertain to a world beyond the natural world. Metaphysical poetry often is contrasted with cavalier poetry.

The Cavalier Poets

The name cavalierliterally means knight; used to describe the followers of Charles I, the gentlemen soldiers who supported the monarchy during the English Civil War, which literally means knight, described the followers of Charles I, the gentlemen soldiers who supported the monarchy during the English Civil War. The Cavalier poets wrote light-hearted poetry that seldom had the depth of philosophical thought evident in metaphysical poetry. Often, as in the case of Herrick’s “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time,” the poetry was seduction poetry, concerned with the physical pleasures of life.

Drama and the Theatre

Although Shakespeare continued writing plays through the first decade of the 17th century and renamed his company of actors The King’s Men in honor of King James I, the early part of the 17th century is not noted for its drama. Ben Jonson, Beaumont and Fletcher, and other playwrights wrote for the stage, although like Shakespeare they are often considered to belong to the Elizabethan Age. Under Puritan influence, drama and the theaters declined until in 1642 Parliament shut down the theaters completely.

Key Takeaways

- The political and religious turmoil of the 17th century influenced the literature of the era in the same way that such struggles affected Renaissance literature.

- The work of Shakespeare and the writing of the King James Bible influenced early modern English.

- Metaphysical poetry and cavalier poetry are significant movements in early 17th-century poetry.

- The Puritan government closed theatres in 1642, resulting in a dearth of English drama.

Resources

Background

- “The Case of England.” Richard Hooker. The European Enlightenment. Washington State University.

- “Citizenship 1625–1789.” The National Archives. Exhibitions. Citizenship.

- Glorious Revolution: England in the 17th Century. Harold Damerow. Union County College, Cranford, New Jersey.

- “The Gunpowder Plot.” Bruce Robinson. BBC History. BBC.

- “The Gunpowder Plot.” Folger Shakespeare Library.

- “The Gunpowder Plot.” John H. Lienhard. Engines of Our Ingenuity. University of Houston. text and audio.

- “Gunpowder Plot CGI.” BBC History. BBC. computer generated video depicting the Gunpowder Plot.

- “History of Great Britain (from 1707).” Bamber Gascoigne. HistoryWorld.

- “Parliament in 1605.” The Gunpowder Plot: Parliament and Treason 1605. UK Parliament Website.

- “People.” The Gunpowder Plot: Parliament and Treason 1605. UK Parliament Website.

- “Rise of Parliament.” The National Archives. Exhibitions. Citizenship.

James I

- “Divine Right of Kings.” Spartacus. Schoolnet.co.uk.

- “James I of England (1566–1625).” John Butler. Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “James I (1603–25).” Britannia.

Puritan Revolution

- “1642–49: Civil Wars.” Historical Outline of Restoration and 18th-Century British Literature. Alok Yadav. George Mason University.

- “English Civil War.” Literary Metamorphoses. Colorado College.

- “Overview: Civil War and Revolution: 1603–1714.” Mark Stoyle. British History In-depth. BBC.

- “The Puritan Revolution.” Folger Shakespeare Library.

- “The Puritan Revolution.” Voices for Tolerance in an Age of Persecution. Folger Shakespeare Library.

- “Puritanism in England.” David Cody and George Landow. The Victorian Web. Brown University.

Charles I

- “1649 Confessions of Charles I’s Executioner.” English Language & Literature Timeline. British Library.

- “Charles I.” The Official Website of the British Monarchy.

- “King Charles I.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium Encyclopedia Project. rpt. from Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed. Vol V. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. 934.

- “Trial of Charles I.” The National Archives.

- “The Trial and Execution of Charles I.” History of Parliament Podcasts. http://www.parliament.uk.

- “The Execution of Charles I 1649.” EyeWitness to History.com.

Oliver Cromwell

- “Oliver Cromwell.” David Cody. The Victorian Web.

- “Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658)“ Historic Figures. BBC.

- “Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658).” Great Britons: Treasures from the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Interregnum

- “Interregnum (1649–1660).” The Official Website of the British Monarchy.

- “Interregnum.” Historical Outline of Restoration and 18th-Century British Literature. Alok Yadav. George Mason University.

- “Interregnum (1649–60).” Historical Outline of Restoration and 18th-Century British Literature. Alok Yadav. George Mason University.

King James Bible

- “The Holy Bible.” Furness Collection. Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text & Image. University of Pennsylvania Libraries.

- “King James Bible.” Online Gallery: Sacred Texts. British Library.

- “King James Bible.” Taking Liberties: The Struggle for Britain’s Freedoms and Rights. British Library.

- King James Bible. Suzanne Kemmer. “A Brief History of English, with Chronology” Words in English.

- Shakespeare’s Legacy. Suzanne Kemmer. “A Brief History of English, with Chronology.” Words in English.

Metaphysical Poetry

- “Introduction.” Bartleby.com. rpt. from Herbert J.C. Grierson, ed. (1886–1960). Metaphysical Lyrics & Poems of the 17th C. 1921.

- “Metaphysical Poets.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt. from The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English. Ian Ousby, ed. Cambridge University Press, 1998. 623.

Cavalier Poetry

- “Cavalier Poetry.” Jack Lynch. Glossary of Literary and Rhetorical Terms. Rutgers University.

- “The Cavalier Poets.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt. from Robin Skelton. The Cavalier Poets. London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1960. 9–10.

17th Century Drama

- “The Closing of the Theatres.” Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “The Closure of the Theaters by the Puritans.” Theater Database. rpt. from Henry Barton Baker. English Actors: From Shakespeare to Macready. New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1879. 27–35.

4.2 John Donne (1572–1631)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- List characteristics of metaphysical poetry and apply them to the poetry of John Donne.

- Define metaphysical conceit, paradox, apostrophe, and allusion, and identify examples in Donne’s poetry.

Biography

Born into a Catholic family at a time when it was illegal to openly practice the Roman Catholic faith, John Donne is the chief figure in a group that has come to be known as the Metaphysical Poets. Donne held a series of clerical positions and enjoyed a prosperous life until he secretly married a relative of his employer. Fired from his position and imprisoned, Donne pleaded with his father-in-law not to punish him and his new wife, but to no avail. Because of his father-in-law’s influence and because of his Catholic background, Donne and his wife lived in poverty for many years until reconciled with his father-in-law.

Donne’s effigy in St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Donne began to question his faith after his brother died while in prison for harboring a Roman Catholic priest, and he continued his struggle with his religious beliefs until he renounced his Roman Catholic faith. Two works in which Donne denounced Roman Catholicism caught the attention of King James I. Donne became an Anglican clergyman at the King’s insistence, later becoming the Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, a prestigious and well-paying position, but one in which Donne was never completely comfortable.

Also go to 1630s in the British Library’s English Language and Literature Timeline to read about John Donne.

Characteristics of Metaphysical Poetry

As previously noted, John Donne is the most noted member of a group of poets known as the Metaphysical Poetspoets whose work explores subjects beyond the physical world, including spiritual matters, poets whose work explores subjects beyond the physical world, including emotional and spiritual matters. They were not recognized as a group or given that name until Samuel Johnson applied it to them in the 18th century. Their poetry shares the following characteristics:

- abrupt, dramatic openings, often with a vivid image or an exclamation

- an argumentative construction

- an introspective quality; an element of self-analysis

- use of the metaphysical conceitan unusual, elaborate, and unexpected comparison, an unusual, elaborate, and unexpected comparison. For example, in his poem “The Bait“ the speaker compares the woman he loves to fish bait. We might expect a comparison to a rose or a beautiful summer’s day but not to fish bait.)

-

use of literary devices

- paradoxan apparently self-contradictory statement—an apparently self-contradictory statement

- apostrophean address to an inanimate object or abstract quality, for example speaking to the moon or to death—an address to an inanimate object or abstract quality, for example speaking to the moon or to death

- allusiona reference to something from history, literature, or any other field that the writer assumes the reader will know—a reference to something from history, literature, or any other field that the writer assumes the reader will know; for example, when Donne refers to those destroyed by “the flood,” he assumes the reader will recognize the biblical allusion to Noah’s flood

“A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning”

| AS virtuous men pass mildly away, | |

| And whisper to their souls to go, | |

| Whilst some of their sad friends do say, | |

| “Now his breath goes,” and some say, “No.” | |

| So let us melt, and make no noise, | 5 |

| No tear-floods, nor sigh-tempests move ; | |

| ‘Twere profanation of our joys | |

| To tell the laity our love. | |

| Moving of th’ earth brings harms and fears ; | |

| Men reckon what it did, and meant ; | 10 |

| But trepidation of the spheres, | |

| Though greater far, is innocent. | |

| Dull sublunary lovers’ love | |

| —Whose soul is sense—cannot admit | |

| Of absence, ‘cause it doth remove | 15 |

| The thing which elemented it. | |

| But we by a love so much refined, | |

| That ourselves know not what it is, | |

| Inter-assurèd of the mind, | |

| Care less, eyes, lips and hands to miss. | 20 |

| Our two souls therefore, which are one, | |

| Though I must go, endure not yet | |

| A breach, but an expansion, | |

| Like gold to aery thinness beat. | |

| If they be two, they are two so | 25 |

| As stiff twin compasses are two ; | |

| Thy soul, the fix’d foot, makes no show | |

| To move, but doth, if th’ other do. | |

| And though it in the centre sit, | |

| Yet, when the other far doth roam, | 30 |

| It leans, and hearkens after it, | |

| And grows erect, as that comes home. | |

| Such wilt thou be to me, who must, | |

| Like th’ other foot, obliquely run ; | |

| Thy firmness makes my circle just, | 35 |

| And makes me end where I begun. |

According to tradition, this poem has an autobiographical significance: that Donne wrote the poem to comfort his wife when he was planning to be away on a business trip for an extended time.

The word valediction means farewell. It shares the same Latin root as the term valedictorian, the person who traditionally gives a “farewell to high school” speech at graduation ceremonies. The title states that this is a farewell that forbids mourning—that the speaker does not want his beloved to mourn when he leaves.

The poem begins with a vivid image: a virtuous man dying so peacefully that the friends gathered around his bed aren’t sure when his breath ceases.

The entire poem is a series of images describing the lovers’ parting:

- In stanza two the lovers part as silently and gently as ice melts; the speaker states there will be no floods of tears or storms of sighing; the sanctity of their love is compared to religious devotion which “laity” (those who don’t have the same degree of sanctified love) do not understand.

- Stanza three pictures the fear caused by earthquakes. Then the speaker notes that the movement of the planets (“trepidation of the spheres”) is a far larger, more significant movement, but no one pays attention to the movement of the earth on its axis or around the sun. By implication, the speaker compares the significance of their parting to the movement of the planets but also wants their leave taking to be as calm.

- Stanza four compares the couple to “sublunary” lovers. Sublunary (sub-lunar) means beneath the moon, suggesting normal, everyday lovers rather than those like the speaker and his beloved who have an elevated, sanctified level of love. Sublunary love can’t withstand parting.

- In stanza five, the speaker claims that sublunary love depends on physical presence. His love, however, is not just a physical passion and therefore does not depend on “eyes, lips, and hands” to exist.

- Stanza six begins with a biblical allusion, a reference to the biblical statement that in marriage, two become one. Even though the speaker is leaving, the bond of their souls will not be broken; instead it will expand as gold can be stretched so thinly that it becomes translucent. Comparing their love to gold also suggests a high value, compressing more meaning into the stanza by using an image rather than a direct statement.

- The last three stanzas include one of the most famous of metaphysical conceits. The speaker compares the couple’s two souls to the two legs of a drafting compass. The speaker compares himself to the leg of the compass that moves to draw a circle and the wife to the stationary leg in the middle that brings the other leg back to the same spot where it began, thus suggesting that the speaker will return home.

God as Architect medieval image of a compass.

Holy Sonnets

“Holy Sonnet V”

I am a little world made cunningly

Of elements, and an angelic sprite ;

But black sin hath betray’d to endless night

My world’s both parts, and, O, both parts must die.

You which beyond that heaven which was most high

Have found new spheres, and of new land can write,

Pour new seas in mine eyes, that so I might

Drown my world with my weeping earnestly,

Or wash it if it must be drown’d no more.

But O, it must be burnt ; alas ! the fire

Of lust and envy burnt it heretofore,

And made it fouler ; let their flames retire,

And burn me, O Lord, with a fiery zeal

Of Thee and Thy house, which doth in eating heal.

In the first two lines, the speaker compares himself to a “little world” made of the physical (“elements”) and the spiritual (“sprite”). Both parts, however, have been betrayed by sin, and the speaker will therefore die both physically and spiritually. In line 5, the speaker addresses God, asking him to pour “seas” of tears into his eyes that will drown or wash away his sin. In the last six lines, the speaker, addressing God, suggests an alternative to washing away his sin: to burn his sin away. The fires of lust and envy made his soul dirty, as smoke and flames leave stains, but paradoxically God’s fire will cleanse and heal his soul.

“Holy Sonnet VII”

At the round earth’s imagined corners blow

Your trumpets, angels, and arise, arise

From death, you numberless infinities

Of souls, and to your scattered bodies go ;

All whom the flood did, and fire shall o’erthrow,

All whom war, dea[r]th, age, agues, tyrannies,

Despair, law, chance hath slain, and you, whose eyes

Shall behold God, and never taste death’s woe.

But let them sleep, Lord, and me mourn a space ;

For, if above all these my sins abound,

‘Tis late to ask abundance of Thy grace,

When we are there. Here on this lowly ground,

Teach me how to repent, for that’s as good

As if Thou hadst seal’d my pardon with Thy blood.

This sonnet begins with a biblical image, angels blowing their trumpets at the four corners of the world to announce the last judgment. The speaker pictures the souls of the dead throughout the ages rising and returning to their bodies. In the next four lines, the speaker recounts numerous ways in which these souls may have met their death: flood, fire, war, dearth (famine), age, sickness, tyrants (executions by tyrants), despair (a word which in the 16th and 17th centuries suggested suicide), law (executions ordered by the legal courts), and chance (accidents). Line 7 addresses one last group of people who will hear the trumpets: those who are still alive, whose “eyes shall behold God” even though they have never experienced death. In the last six lines, the speaker asks God to let the dead sleep awhile longer. His reason for this request is that he needs time to repent.

“Holy Sonnet X”

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so ;

For those, whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow,

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleep, which but thy picture[s] be,

Much pleasure, then from thee much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee do go,

Rest of their bones, and soul’s delivery.

Thou’rt slave to Fate, chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell,

And poppy, or charms can make us sleep as well,

And better than thy stroke ; why swell’st thou then ?

One short sleep past, we wake eternally,

And Death shall be no more ; Death, thou shalt die.

Perhaps the most well-known of the Holy Sonnets, “Holy Sonnet X” begins with a statement to death personified, a forceful statement ordering death not to be proud. The speaker continues to address death, claiming that those death thinks it has conquered have not really died. Death, the speaker asserts, is subject to a list of causes: fate, chance, kings, suicide, poison, war, and sickness. In the last two lines, the speaker makes his final statement of victory over death. In line 2—”for thou art not so”—and in the final sentence—”Death, thou shalt die” the use of one-syllable words emphasizes the power of the words with an accent on each word.

Key Takeaways

- John Donne is the chief figure of the Metaphysical Poets.

- Metaphysical poetry is characterized by dramatic openings, argumentative construction, self-analysis, metaphysical conceits, and literary devices such as paradox, apostrophe, and allusion.

Exercises

- The titles of metaphysical poems are often important indications of the content and main idea of the poem. What is a valediction? What does the title reveal about the attitude the speaker has toward his leave-taking?

- John Donne’s poem “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning,” like most metaphysical poems, is a series of comparisons (metaphysical conceits). The poem begins with an image—a comparison—as signaled by the word “As.” Assuming the biographical interpretation—that the speaker of the poem is addressing his wife—to what does the speaker compare their leave-taking?

- Why, according to stanza 4, does physical absence destroy some people’s love? How is this different from the speaker’s love (stanza 5)? Which type of love do you think was portrayed in Sidney’s sonnets?

- Unlike the usual Elizabethan sonnet sequences about human love, Donne’s Holy Sonnets trace his spiritual relationship with God. How would you describe the relationship in each of the sonnets discussed?

- Identify each of the Holy Sonnets discussed as English or Italian. What characteristics of structure and content affect your classification?

- Review the list of characteristics of metaphysical poetry. Identify characteristics in each of the sonnets discussed.

Resources

Biography

- John Donne 1572–1631. Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “John Donne’s Marriage Letters.” Folger Shakespeare Library.

Texts

- “Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions.” Project Gutenberg.

- DigitalDonne: the Online Variorum. Gary A. Stringer, General Editor. Department of English. Texas A&M University. digital images of manuscripts, text of some poems, concordance.

- “John Donne Sermons.” Brigham Young University. Harold B. Lee Library.

- “Selected Poetry of John Donne (1572–1631).” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “The Works of John Donne.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

Audio

- “Death Be Not Proud.” Project Gutenberg.

- “The Holy Sonnets.” Books Should Be Free.

- “John Donne.” LibriVox.

- “The Metaphysical Poets.” BBC Radio 4 Programmes. In Our Time. recording of panel of British university professors discussing metaphysical poetry.

- “The Works of John Donne.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. audio of selected works.

Metaphysical Poetry

- “1633 John Donne Poetry.” English Language & Literature Timeline. British Library.

Video

- “John Donne.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

4.3 Andrew Marvell (1621–1678)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Analyze characteristics of metaphysical poetry in the works of Andrew Marvell.

- Recognize the effects of the English Civil War on Marvell’s production of literature.

- Explain the carpe diem philosophy as seen in “To His Coy Mistress.”

Biography

The son of a clergyman, Andrew Marvell was educated at Cambridge University. After working as a tutor and traveling extensively, Marvell served with John Milton in government posts and may have been instrumental in helping Milton avoid severe punishment, even a death sentence, after the Restoration. Marvell was, for a time, a supporter of King Charles I, but he then changed his allegiance to Oliver Cromwell and the commonwealth government. During the Interregnum, Marvell was elected as a Member of Parliament representing his hometown of Hull. He wrote several poems praising Oliver Cromwell and, after the Restoration, works critical of the court of Charles II even though his earlier work honored the reign of Charles I.

Statue of Andrew Marvell in Trinity Square in Marvell’s hometown of Hull, England—Trinity Square is bordered on one side by Trinity Church where Marvell’s father was a clergyman and on another side by the 16th-century building where Marvell attended grammar school.

“To His Coy Mistress”

Andrew Marvell is considered one of the metaphysical poets. Like John Donne, he wrote poems that relied on metaphysical conceits, the witty, elaborate comparisons that characterize metaphysical poetry. Also like Donne, many of his poems debate spiritual issues and the transitory nature of life. Even the poem that is probably Marvell’s best known, “To His Coy Mistress,” soon turns from seduction to metaphysical speculation. The poem is a seduction poem and a statement of carpe diema Latin phrase translated as “seize the day”, a Latin phrase translated as “seize the day.” The carpe diem philosophy encourages living life to the fullest in the present moment—the “eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow you die” outlook on life.

“To His Coy Mistress”

| Had we but world enough, and time, | |

| This coyness, lady, were no crime. | |

| We would sit down and think which way | |

| To walk, and pass our long love’s day; | |

| Thou by the Indian Ganges’ side | |

| Shouldst rubies find; I by the tide | |

| Of Humber would complain. I would | |

| Love you ten years before the Flood; | |

| And you should, if you please, refuse | |

| Till the conversion of the Jews. | |

| My vegetable love should grow | |

| Vaster than empires, and more slow. | |

| An hundred years should go to praise | |

| Thine eyes, and on thy forehead gaze; | |

| Two hundred to adore each breast, | |

| But thirty thousand to the rest; | |

| An age at least to every part, | |

| And the last age should show your heart. | |

| For, lady, you deserve this state, | |

| Nor would I love at lower rate. | |

| But at my back I always hear | |

| Time’s winged chariot hurrying near; | 22 |

| And yonder all before us lie | |

| Deserts of vast eternity. | |

| Thy beauty shall no more be found, | 25 |

| Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound | |

| My echoing song; then worms shall try | |

| That long preserv’d virginity, | |

| And your quaint honour turn to dust, | 29 |

| And into ashes all my lust. | |

| The grave’s a fine and private place, | |

| But none I think do there embrace. | |

| Now therefore, while the youthful hue | |

| Sits on thy skin like morning dew, | |

| And while thy willing soul transpires | |

| At every pore with instant fires, | 36 |

| Now let us sport us while we may; | |

| And now, like am’rous birds of prey, | |

| Rather at once our time devour, | |

| Than languish in his slow-chapp’d power. | |

| Let us roll all our strength, and all | |

| Our sweetness, up into one ball; | |

| And tear our pleasures with rough strife | |

| Thorough the iron gates of life. | |

| Thus, though we cannot make our sun | |

| Stand still, yet we will make him run. |

William Holman Hunt The Hireling Shepherd.

Marvell’s poem urges a young woman to give in to love-making while she is young and desirable. The speaker of this poem begins his persuasive speech by telling her that her coyness would be acceptable if the couple had unlimited time. But he emphasizes the passing of time with the well-known image of “time’s winged chariot hurrying near” (line 22). He pictures the young woman in her tomb where she will no longer be beautiful (line 25) and where her “quaint honor” will “turn to dust” (29). The third and last stanza begins with the word “now,” emphasizing the need to enjoy life’s physical pleasures before death steals them. Now, while she is beautiful and their youthful passions spring into “instant fires” (36), they should consume their time by making full use of it while they have time and youth. The speaker, in the final couplet, notes that while they cannot make time (“our sun”) stand still, they can race against time by using their time to the utmost. Also suggested is the familiar idea that time flies when a person is enjoying him/herself, indicating that the sun will run quickly through the day if they are engaged in the pleasurable physical activity the speaker advocates.

Key Takeaways

- Andrew Marvell is a metaphysical poet whose poetry displays the typical characteristics of metaphysical poetry.

- Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress” exemplifies the carpe diem tradition.

Exercises

- Review the list of characteristics of metaphysical poetry in the section on John Donne. What examples of those characteristics do you find in “To His Coy Mistress”?

- This poem is a seduction poem, an attempt by the speaker to persuade a young woman to make love with him. What arguments does he use to try to persuade her?

- How convincing do you consider his argument?

Resources

Biography

- “Andrew Marvell (1621–1678).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Andrew Marvell.” Poets.org. Academy of American Poets.

- “Andrew Marvell.” rpt. from The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21). Volume VII. Cavalier and Puritan. Bartleby.com.

- “Andrew Marvell: Chronology of Important Dates.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

Text

- “To His Coy Mistress.” Annotations by Dr. K. Wheeler. Carson-Newman College.

- “To His Coy Mistress.” Commentary by Michael Weiser. Thomas Nelson Community College.

- “To His Coy Mistress.” “Marvell, Andrew. Miscellaneous Poems.” Electronic Text Center. University of Virginia Library.

- “To His Coy Mistress.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “The Works of Andrew Marvell.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

Audio

- “To His Coy Mistress.” Project Gutenberg.

- “To His Coy Mistress.” LibriVox.

4.4 Robert Herrick (1591–1674)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify Robert Herrick as a cavalier poet.

- Recognize the carpe diem tradition in Herrick’s “To the Virgins.”

Biography

Robert Herrick is considered a cavalier poet, one of the followers of Charles I. In fact, coming from a middle class background, he enjoyed the patronage of several noblemen and was thus welcomed into court gatherings. As was common in England since the time of Chaucer, poets circulated their poetry in manuscript form for the amusement of the court. Poems written in honor of a specific nobleman or at the request of a nobleman as a memorial for a special occasion were often rewarded monetarily. Herrick’s poetry not only provided him with needed income from his patrons, it also made him a part of the courtly social and literary circles. After becoming an Anglican clergyman, Herrick served as chaplain to a high-ranking courtier. Soon after, however, King Charles I appointed him vicar of a church in Exeter, far from the social and literary life Herrick loved in London. After the execution of Charles I, Herrick lost his position as vicar under Cromwell’s rule and returned to London where he concentrated on publishing his poems. When Charles II was restored to the throne, Herrick’s job was also restored, and he spent the rest of his life as a vicar in Exeter.

“To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time”

Sundial on the side of a building in Yvoire, Haute-Savoie, France.

aewolf from Denver. Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license

To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time

Gather ye rosebuds while ye may,

Old time is still a-flying :

And this same flower that smiles to-day

To-morrow will be dying.

The glorious lamp of heaven, the sun,

The higher he’s a-getting,

The sooner will his race be run,

And nearer he’s to setting.

That age is best which is the first,

When youth and blood are warmer;

But being spent, the worse, and worst

Times still succeed the former.

Then be not coy, but use your time,

And while ye may go marry :

For having lost but once your prime

You may for ever tarry.

John William Waterhouse “Gather ye rose-buds, while ye may.”

As is typical of the Cavalier Poets, Herrick expresses the carpe diem, seize the day, philosophy in this poem, the philosophy that life is to be lived for today because tomorrow is uncertain. Unlike Marvell’s seduction poem, this poem specifically encourages young women to marry, not simply to engage in sexual activity for pleasure’s sake.

Herrick’s poem begins with the well-known lines, “Gather ye rosebuds while ye may, / Old time is still a-flying.” These lines embody the carpe diem philosophy: young women should make the most of their youth and loveliness because it won’t last long. Herrick emphasizes the transitory nature of youth and beauty as he compares the young women to flowers which bloom one day and wilt the next (lines 3–4). Noting that youth is the best age (lines 9–10), Herrick in the final stanza again urges the virgins to marry while they are young and desirable.

Key Takeaways

- Robert Herrick is an example of a cavalier poet.

- Herrick’s “To the Virgins” exemplifies the carpe diem tradition.

Exercises

- In the first stanza, the speaker directly addresses the young maidens, urging them to “gather [their] rosebuds” while they can and to be aware of time passing. The speaker is obviously referring to more than literally picking flowers. What does the admonition to gather rosebuds represent?

- What does the flower of line 3 represent?

- The second stanza pictures the sun racing across the sky to set at the end of the day. What does the passage of the day represent? How would you compare this use of sun imagery with that in Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress”?

- The speaker claims that youth, the “first” part of a person’s life is the best because “youth and blood are warmer.” What does the speaker suggest with the reference to warm blood?

- What does the word coy mean in the last stanza? How would you compare Herrick’s use of the word coy with Marvell’s use of the word in “To His Coy Mistress”? What is the significance, in both poems, of young women being referred to as coy?

- What warning does the speaker have for the virgins in the last stanza?

- Compare and contrast how this poem and Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress” depict the carpe diem philosophy.

Resources

Biography

- “Life of Herrick.” rpt. from Robert Herrick. The Works of Robert Herrick. Vol. I. Alfred W. Pollard, Ed. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1891. xv–xxvi.

- “Robert Herrick.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Robert Herrick.” Poets.org. Academy of American Poets.

Text

- “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “To Virgins, to Make Much of Time.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time.” A Selection from the Lyrical Poems of Robert Herrick. Francis Turner Palgrave, editor.

Audio

- “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time.” LoudLit.org. Performer Argos MacCallum. Audio Engineer Warren Smith.

- “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time.” Short Poetry Collection 019. LibriVox.

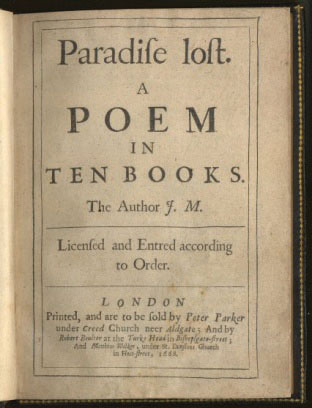

4.5 John Milton (1608–1674)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recount how the Puritan Revolution affected Milton’s literary career.

- List the types of literature Milton wrote and provide examples.

- Define epic and identify the characteristics and conventions of an epic.

- Apply the definition of epic to Milton’s Paradise Lost.

Biography

Born into a financially prosperous middle class family, John Milton was well educated, receiving degrees from Cambridge University. After completing his MA with honors, Milton moved to his father’s home where he spent several years in private study and writing. He also, like most well-to-do young men, undertook an extended trip to the continent, returning to England when civil war seemed imminent.

Referred to as the great Puritan poet, Milton found his fortunes went up and down with the rise and fall of Cromwell’s commonwealth. He accepted a government post as a translator under the commonwealth government, writing treatises supporting republicanism and Oliver Cromwell. During this period, Milton lost his vision and was forced to continue his writing by dictating to assistants, including poet Andrew Marvell. Following the Restoration, a warrant was issued for Milton’s arrest because of his support of Cromwell and the commonwealth government. Milton was arrested and imprisoned for a time until friends, again including poet Andrew Marvell, intervened and won his release, possibly saving Milton from execution. Milton retired to a small cottage in Chalfont St. Giles, where he continued to write until his death in 1674.

In 2008, Christ’s College, Cambridge created a Milton website as part of a celebration of Milton’s 400th birthday. It includes an abundance of information about Milton as well as an interactive study resource on Paradise Lost titled Darkness Visible.

Milton Dictates to His Daughters Delacroix.

Milton’s Literature

Milton wrote several types of literature:

-

poetry

- lyric poems

- sonnets

- longer poems such as “L’Allegro” and “Il Penseroso”

- his elegy Lycidas, written in memory of his friend Edward King

- his most famous work, the epic poem Paradise Lost

- a masquea form of entertainment for the court involving singing and dancing as well as acting, usually with elaborate costumes and sets, a form of entertainment for the court involving singing and dancing as well as acting, usually with elaborate costumes and sets. The lords and ladies of the court sometimes took part in a masque as well as professional entertainers. Milton’s masque Comus, unlike the traditional masque, was not performed at court but in the castle of a nobleman. Its subject was the virtue of chastity rather than the more risqué subjects found in most masques.

- prose works on political and religious topics such as his Divorce Tracts and Areopagitica, a pamphlet arguing for freedom of the press

Texts

- “Books by Milton, John.” Project Gutenberg.

- “The John Milton Reading Room.” Thomas Luxon, Professor of English. Dartmouth College.

- “Selected Poetry of John Milton (1608–1674).” Representative Poetry Online. University of Toronto.

Paradise Lost Text

- Paradise Lost. Project Gutenberg.

- Paradise Lost. The 12-Book 1674 Edition. Michael E Bryson, Department of English. California State University, Northridge.

- Paradise Lost. “The John Milton Reading Room.” Thomas Luxon, Professor of English. Dartmouth College.

- Paradise Lost (1667). Judy Boss. Renascence Editions. text of 1667 edition with 10 books.

Paradise Lost

Milton had long contemplated writing an epic poem before he began Paradise Lost. He first thought of making the Arthurian legends its topic. Then he decided to write about the fall of man—”of man’s first disobedience.” Paradise Lost is considered the greatest epic written in the English language.

The Epic

An epica long narrative poem in elevated style depicting the heroic adventures of a valiant, superhuman individual is a long narrative poem in elevated style depicting the heroic adventures of a valiant, superhuman individual.

Examples of epics include

- Homer’s the Iliad and the Odyssey

- Virgil’s Aeneid

- Beowulf

- The Song of Roland

- Milton’s Paradise Lost

Epics share the following characteristics:

- an epic hero: an historical or legendary individual capable of great deeds that are important to his/her people

- setting: a place of historical or legendary significance at a time crucial to the people of the story

- action: valiant feats requiring great courage and massive strength (physical or, sometimes, psychological)

- supernatural forces: mythological or supernatural figures that intervene in human events

-

style: an imposing, formal style that includes the use of literary and metrical techniques to convey a sense of eloquence and gravity, such as the caesura in Beowulf and in Paradise Lost

- enjambmenta sentence that continues from one line into another in a poem, continuing a thought over two or more lines rather than ending each sentence at the end of each line of poetry (end-stopped poetry)—a sentence that continues from one line into another in a poem, continuing a thought over two or more lines rather than ending each sentence at the end of each line of poetry (end-stopped poetry)

- inversionchanging the normal word order of a sentence—changing the normal word order of a sentence

- elisionomitting a letter or syllable of a word to maintain the meter of a line of poetry—omitting a letter or syllable of a word to maintain the meter of a line of poetry

In addition to these characteristics of epics, epics share a group of conventionstraditional features that are usually employed in a particular genre, traditional features that are usually employed in a particular genre:

- a statement of theme at the beginning of the poem

- the invocation of a muse to inspire and instruct the poet

- a narrative opening in medias resbeginning a narrative in the middle of the action (beginning a narrative in the middle of the action)

- cataloguesa formal list of items such as battleships or warriors (formal lists of items such as battleships or warriors)

- extended formal speeches by the main characters

- epic similessimiles several lines long and developed in great detail (similes several lines long and developed in great detail)

Key Takeaways

- Milton is known as the great Puritan poet.

- Milton wrote a variety of literature including lyric poetry, sonnets, long poems, a masque, an elegy, prose, and the great epic Paradise Lost.

- Paradise Lost displays the characteristics and conventions of the classical epic genre.

Exercises

Identify the characteristics and conventions you find in Paradise Lost:

- epic hero: Literary scholars have not agreed on who the epic hero is in Paradise Lost—or if it has a hero. A clearly heroic figure such as Odysseus or Beowulf is not obvious in Paradise Lost. What reasons could you give for considering Satan, Christ, or Adam as the hero? What reasons would disqualify each character for that designation?

- setting: In what locations do the scenes in Paradise Lost take place? In Book I, describe the scene in which the action begins.

- action: What characters in Paradise Lost could be considered as taking heroic action? Some critics describe Satan as an anti-hero; why?

- supernatural forces: What supernatural forces take part in the action of Paradise Lost?

- style: Describe the style of Paradise Lost. Find examples of literary techniques that add to the elevated, formal style of Paradise Lost such as enjambment, inversion, and elision.

- theme: Locate the introductory lines in which Milton states the theme of Paradise Lost.

- invocation to the muse: What is a muse? What muse does Milton invoke?

- in medias res: In the argument for Book I, Milton states that he plans to open in medias res. After the introductory lines, what is the scene when the action begins in Paradise Lost?

- catalogues: A classical epic might provide a list of warriors in a great battle; what list of names does Milton provide in Book I of Paradise Lost?

- extended formal speeches: Locate examples of formal speeches by Satan and Adam.

- epic similes: Locate examples of epic similes.

Resources

Biography

- “John Milton (1608–74).” John Milton 400th Anniversary Celebrations. Christ’s College, Cambridge University.

- “John Milton & Seventeenth-Century Culture.” From the collections of Thomas Cooper Library based on an exhibit by Patrick Scott. University Libraries Rare Books & Special Collections. University of South Carolina.

- “Life of John Milton (1608–1674).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

Texts

- “Books by Milton, John.” Project Gutenberg.

- “The John Milton Reading Room.” Thomas Luxon, Professor of English. Dartmouth College.

- Open Milton. Open Knowledge Foundation.

- “Selected Poetry of John Milton (1608–1674).” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

Paradise Lost Text

- Paradise Lost. Project Gutenberg.

- Paradise Lost. The 12-Book 1674 Edition. Michael E. Bryson, Department of English. California State University, Northridge.

- Paradise Lost. The John Milton Reading Room. Thomas Luxon, Professor of English. Dartmouth College.

- Paradise Lost (1667). Judy Boss. Renascence Editions. text of 1667 edition with 10 books.

Audio

- “The Lady Margaret Lectures 2008.” Lecture podcasts. John Milton 400th Anniversary Celebrations. Christ’s College, Cambridge University.

- Paradise Lost. LibriVox.

- Paradise Lost. Podcasts of the Readings. John Milton 400th Anniversary Celebrations. Christ’s College, Cambridge University.

- Paradise Lost Audiotexts. John Rumrich. University of Texas.

Video

- “John Milton.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

Images

- The Iconography of Paradise Lost. George Klawitter. St. Edwards University. Austin, Texas.

- “Milton in the Old Library: 400th Anniversary Exhibit.” John Milton 400th Anniversary Celebrations. Christ’s College, Cambridge University. Images from a Cambridge University library exhibit, including images of first editions of Milton’s works and illustrations of Paradise Lost.

- Paradise Lost Illustrated. Don Ulin. University of Pittsburgh.

- “The Paradise Lost of Milton with illustrations.” Designed and engraved by John Martin, 2 vols, 1827. Online Gallery: The Writer in the Garden. The British Library.

Additional Information

- Darkness Visible: A Resource for Studying Milton’s Paradise Lost. John Milton 400th Anniversary Celebrations. Christ’s College, Cambridge University. an interactive source including information on Paradise Lost, Milton’s biography, Milton’s views on religion and politics, influences Milton has had on subsequent literature, illustrations of Paradise Lost, Milton’s language, and critical information.

- “History of the Masque Genre.” John Milton’s A Maske or Comus. Helen L. Hull, Meg F. Pearson, and Erin A. Sadlack. University of Maryland, College Park.

- “John Milton’s Areopigitica.” Taking Liberties: The Struggle for Britain’s Freedoms and Rights. The British Library.

- “Milton’s Works.” John Milton 400th Anniversary Celebrations. Christ’s College, Cambridge University. Lists of Milton’s works alphabetically and chronologically.

- The Poetry of John Milton. Dr. John Rogers, Yale. Open Yale video course. 24 video lectures. Academic Earth.