This is “The Sixteenth Century”, chapter 3 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 3 The Sixteenth Century

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

3.1 The Sixteenth Century

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize the atmosphere of energy and turbulence in the political and religious realms that influenced 16th-century literature, including the ideas of the Renaissance and the Reformation.

- Define the types of literature typical of the 16th century including the sonnet, pastoral poetry, and drama.

- Understand the development of purpose-built theaters and how this development influenced 16th-century drama.

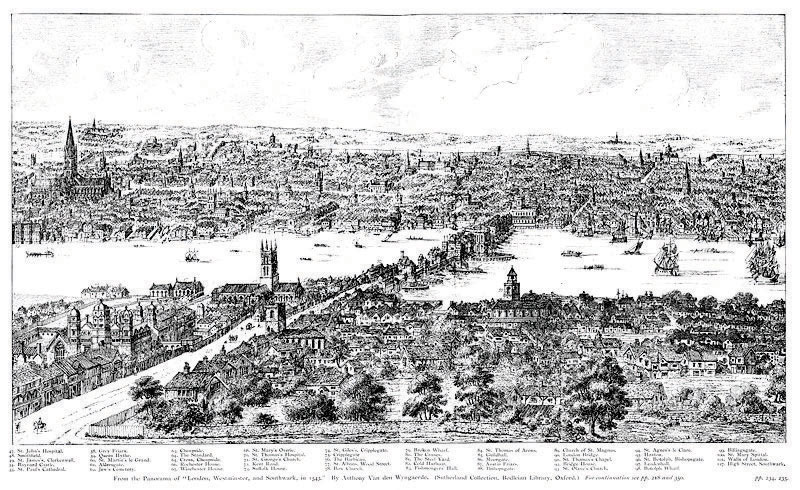

Wyngaerde’s “Panorama of London in 1543.”

Brash, exciting, bustling, expanding, prosperous, dangerous, precarious—all these words describe sixteenth-century England. As a nation, England was sure of herself and her dominance of the seas and the exploration for which names such as Sir Walter Raleigh and Sir Francis Drake became famous. London, which began to thrive with the emerging middle class during the Middle Ages, grew overcrowded and, like the River Thames that flowed through her center, congested with all the flotsam and jetsam of a thriving metropolis. The city incorporated great wealth and beauty next to squalor and wretched poverty. Business and commerce flourished on the river and in the city, but so did crime and disease.

The Tudor Court

The Tudor court echoed all the qualities of the city of London, including the danger and intrigue.

The Tudor Rose—the emblem of the Tudor rulers, symbolizing the unification of the white rose of the Yorks and the red rose of the Lancasters.

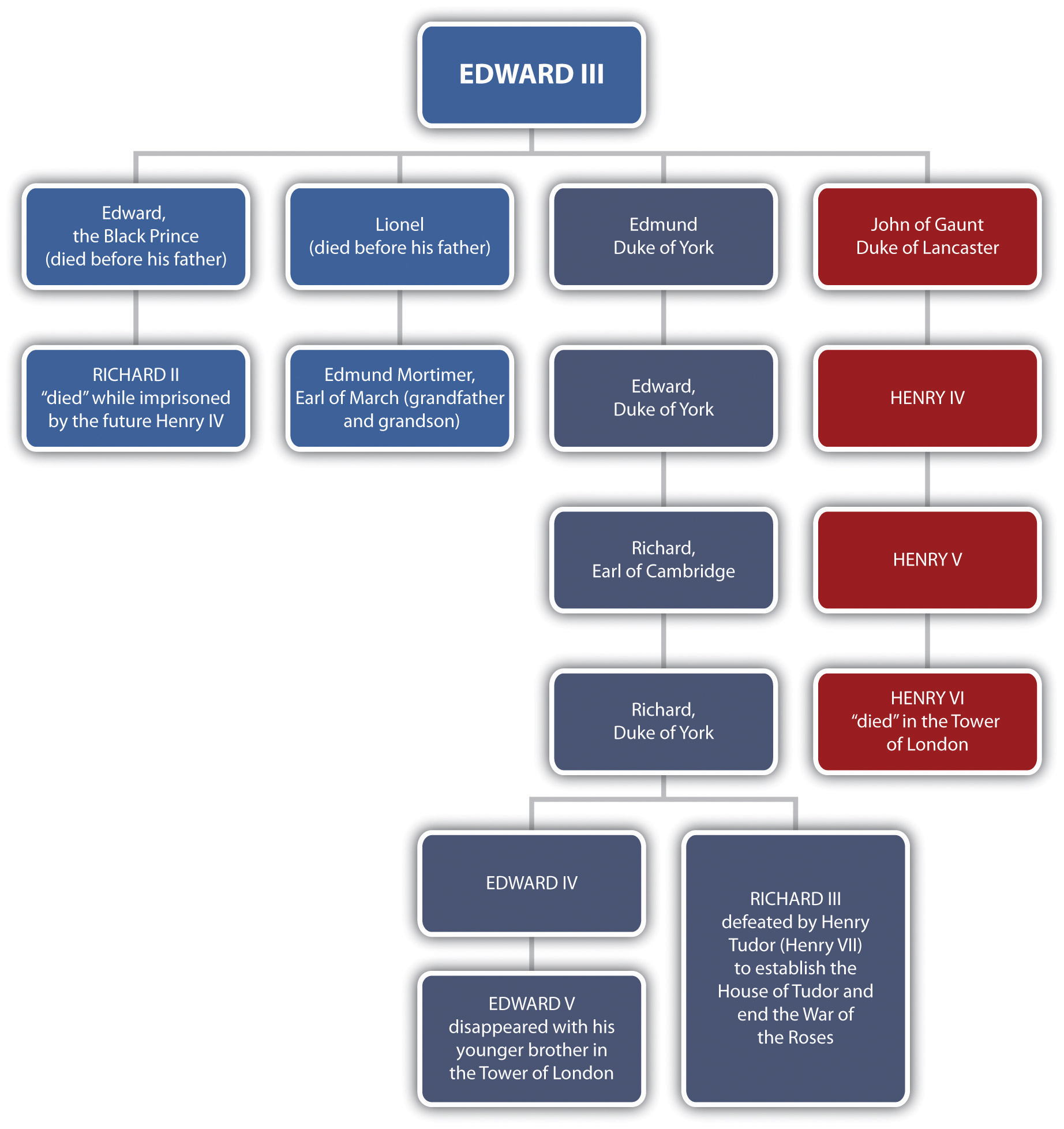

Throughout the last fifty years of the Middle Ages, England was embroiled in civil strife between two branches of the royal Plantagenet family, the Lancasters and the Yorks. Because the emblem of the Lancasters was the red rose and the emblem of the Yorks was the white rose, these battles were referred to as the Wars of the Roses. When Henry Tudor (of the house of Lancaster) defeated Richard III (of the House of York) in 1485, he established the Tudor rulers that provided one of the most powerful yet turbulent dynasties to reign in Britain.

Henry VII

Henry Tudor, King Henry VII, married Elizabeth of York, daughter of Yorkist King Edward IV. Their marriage united the two warring factions of the royal family, bringing an end to the Wars of the Roses. Their son Henry became one of England’s most notorious monarchs, King Henry VIII.

Henry VIII

“The Rose both White and Red

In one Rose now doth grow”

John Skelton

King Henry VIII succeeded to the throne in 1509 ending the Wars of the Roses that had torn England asunder for years, bringing unity to a war-weary country. Unfortunately, Henry VIII soon had the country embroiled in new struggles. Large in physical stature and in character, Henry VIII ruled with an iron hand. He is perhaps remembered most for his six wives. Henry was a second born son; his older brother and the heir apparent Arthur died shortly after he was married to Catherine of Aragon to establish an alliance with Spain. Henry VIII married his brother’s widow, again for dynastic reasons. Years passed, however, without a male heir from their union. Catherine did give birth to a daughter Mary, but Henry felt the need for a male heir to ensure the continuance of the Tudor line.

Henry’s desire to divorce Catherine led to the Reformationthe movement to reform the Roman Catholic Church which led to the establishment of Protestant denominations, the movement to reform the Roman Catholic Church which led to the establishment of Protestant denominations, in England. Although the Reformation, led by Martin Luther, was well under way on the European continent, Henry VIII’s break from the Roman Catholic Church was to suit his own purposes, not a result of his religious convictions. When the Roman Catholic Church refused to grant Henry’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon, Henry declared himself the head of the Church in England, essentially breaking away from the Roman Church and the Pope’s authority and establishing what is now the Anglican Church, the Church of England. With the Act of Supremacy in 1534, Henry VIII became the head of both Church and State. The Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer, appointed by Henry, nullified Henry’s marriage to Catherine, allowing him to marry Anne Boleyn, who gave birth to a daughter Elizabeth. When Anne, too, failed to provide a male heir, Henry had her beheaded based on charges of adultery and incest, accusations many historians believe to be false. He soon married Jane Seymour, who finally gave Henry his long-awaited male heir, Edward.

Edward VI

Upon Henry VIII’s death in 1547, his nine-year-old son became King Edward VI. Because of his age and frail health, a bevy of relatives and advisors attempted to control the throne through the young king. He died at age 15, after attempting to exclude his sisters from ascending to the throne.

Mary I

Henry VIII’s older daughter Mary I was, like her mother Catherine of Aragon, devoutly Roman Catholic. Her accession to the throne brought about a return to the Roman Catholic Church as the official church in England. Just as her father Henry VIII had persecuted those who refused to renounce their Catholic faith and acknowledge him rather than the Pope as head of the Church, Mary I persecuted those who resisted the return to the Roman Catholic faith. Possibly as many as three hundred people were burned at the stake as heretics under her rule, earning her the nickname Bloody Mary. One of those burned at the stake was Archbishop Cranmer who had granted her father’s divorce from her mother.

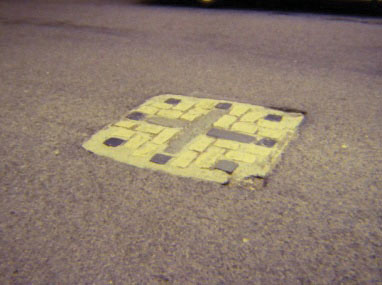

This cross in Broad Street in the city of Oxford marks the place where three bishops, Ridley, Latimer, and Cranmer, were burned at the stake on the orders of Mary I.

Elizabeth I

When Mary I died in 1558, the last surviving child of Henry VIII became Queen Elizabeth I and led England into a time of prosperity, predominance in world power, and relative religious peace at home. Although she restored the Protestant Church of England her father had established, she was more tolerant in her religious governing than either her father or her sister Bloody Mary had been. The defeat of the Spanish Armada established England as a dominant naval power, and English explorers established colonies that set the stage for the British Empire of the 19th century. Her reign is considered a Golden Age for England, an era often referred to as the Elizabethan Age.

The English Renaissance

The word renaissanceliterally means “re-birth”; generally used to refer to a renewed interest in classical learning and a desire to seek new knowledge literally means “re-birth” and is generally used to refer to a renewed interest in classical learning and a desire to seek new knowledge. Beginning in Italy in the early 14th century, the Renaissance (a term not used until modern times) spread to Britain in the 16th century. The English Renaissance provided fertile ground for literature. Renaissance ideas included an emphasis on education that led to increased literacy and an emphasis on form and order that affected the types of literature produced in 16th-century Britain.

Literature

The architectural style of Elizabethan stately homes reveals a penchant for symmetry and order. To honor Henry VIII or Elizabeth I, great houses were sometimes built in the shape of the letters H or E. The knot garden and topiary also became popular ornamentation on great estates.

Figure 3.1

In Figure 3.1., the contemporary garden at Broughton Castle, is a knot garden, a garden with clearly defined lines and boundaries forming geometric shapes.

Figure 3.2

In Figure 3.2., this contemporary garden is at Hampton Court Palace, originally the home of Henry VIII’s advisor Cardinal Wolsey, and then, at Henry’s suggestion, the home of the King and his second queen, Anne Boleyn. Note the flowers planted in colorful but orderly straight rows and the bushes trimmed to geometrical shapes.

Figure 3.3

As seen in Figure 3.3., at Hampton Court Palace, even the trees were trimmed into artificial shapes.

This preference for symmetry and order is seen not only in Elizabethan houses and gardens, but also in the literature of the 16th century. Reflecting a belief that art was nature improved by human enhancement, the literature of the period often used structured forms and styles such as the sonnet and the Spenserian stanza.

The Sonnet

In an age which valued highly structured poetry, the sonneta poem of 14 lines and a set rhyme scheme, a poem of 14 lines and a set rhyme scheme, was one of the most popular forms. The Sonnet Central Time Line illustrates the concentration of sonnets written during the 16th and early 17th century, as well as a later renewed interest in sonnets during the 19th century.

PowerPoint 3.1.

Follow-along file: PowerPoint title and URL to come.

The Pastoral Mode

In the Elizabethan courtier’s world of political maneuvering for status with the monarch, intrigue and betrayal by others also striving for power, it’s not surprising that the classical idea of otium, a peaceful leisure filled with art and nature, appealed to courtier/writers.

Derived from the Latin root word pastor, meaning shepherd, the pastoral modea type of literature that portrays shepherds in an idealized rural setting, engaging in contests of singing or poetry, flirting with country maidens, watching their flocks in a peaceful and beautiful natural world is a type of literature that portrays shepherds in an idealized rural setting, engaging in contests of singing or poetry, flirting with country maidens, watching their flocks in a peaceful and beautiful natural world. Although this idealized, fairy-tale world bore little resemblance to the lives of peasants who actually attempted to make a living raising sheep, the pastoral mode charmed the courtier whose life and fortune depended not just on his skills in battle but also on the vagaries of the monarch.

Drama

In 1576, James Burbage built the first theater in London, aptly named The Theatre. Before dedicated theaters were built, plays were often performed in the yards of coaching inns, open cobblestone areas where coaches stopped for passengers to eat, rest, or stay overnight at the inn. Many inns had galleries, covered walkways or balconies on the second floor leading to rooms that could be rented. When a play was performed, the audience could stand in the yard or pay extra to stand on one of the galleries for a better view. This basic layout was followed in the design of Elizabethan theatres.

The George Inn, the only remaining galleried inn in London.

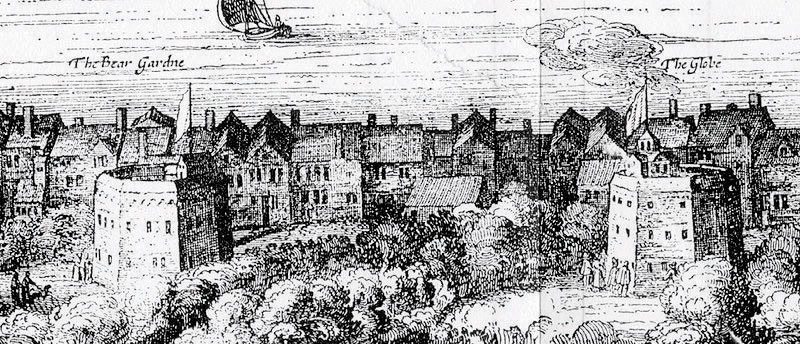

A few drawings from the 16th century provide information about how 16th-century theatres, including the Rose, were designed. Internet Shakespeare Editions from the University of Victoria provides an interactive look at a 16th century stage, and the Folger Shakespeare Library explains the origins and the workings of the theatres familiar to Shakespeare.

Replica of the Globe in London.

Although not the first of Elizabethan theatres, the Globe is the most well-known and the most closely associated with Shakespeare.

Wesleyan University provides a 3-D model of the Globe Theatre and an animation of how the parts of the stage might have been used in the graveyard scene from Hamlet. Clemson University provides a virtual tour of the Globe Theatre as it likely appeared in Shakespeare’s time. Shakespeare’s Globe in London, a replica of the original Globe theatre, offers a virtual tour of this contemporary active theatre. Although designed for children, Cambridge University’s Converse program presents an entertaining and informative interactive animation depicting the 16th-century play-going experience.

Nicholas Visscher’s map of the City of London (1616), showing the Globe Theatre.

The “University Wits”

While Shakespeare’s name dominates English Renaissance drama, he was not the only, or even the first, dramatist of the era. Preceding Shakespeare was a group of playwrights known as the “University Wits.” Perhaps the best known of the University Wits, Christopher Marlowe developed what Ben Jonson called “Marlowe’s mighty line,” the sonorous use of blank verse also employed by Shakespeare.

Shakespearean drama represents a high point unequaled in literature. On the heels of the flowering of Elizabethan drama, the Puritans shut down the theatres in England. Thus, a dearth of drama quickly followed the wealth of Shakespeare’s time period.

Key Takeaways

- The 16th century was a highlight in British history, resulting in literature that reflected the vitality but also the turbulence of the period.

- Highly structured forms of literature such as the sonnet, the Spenserian stanza, and the blank verse of Marlowe’s and Shakespeare’s drama reflected the Renaissance’s interest in classical literature.

- Literature written in the pastoral mode reflected a desire for a simple, peaceful existence away from the intrigue of court life.

- The 16th century saw the development of purpose-built theaters.

Resources

Background

- “City Life.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “The City of London.” Life in Elizabethan London. A Compendium of Common Knowledge.

- “Elizabethan England.” Shakespeare Resource Center.

- “London Bridge Virtual Tour.” British History In-Depth. BBC.

- “Sir Francis Drake.” Historic Figures. BBC.

The Tudor Court

- Anne Boleyn. Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Catherine of Aragon.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Court Politics.” History of England. Britain Express.

- “Edward VI.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Elizabeth.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Elizabeth I: An Overview.” Alexandra Briscoe. BBC. British History In-Depth.

- “Elizabeth of York.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Elizabethan Life.” History of England. Britain Express.

- “Henry VIII and the Break with Rome.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “Jane Seymour.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “King Henry VIII.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “Queen Mary I.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “The Act of Supremacy.” National Archives.

- “The Reformation.” E. L. Skip Knox. Boise State University.

- “The Six Wives of Henry VIII.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “The Spanish Armada.” Simon Adams. BBC. British History In-Depth.

- “The Wars of the Roses.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- “The Wars of the Roses.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

The English Renaissance

- “Education.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “Putting Nature in Order.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “A Rebirth of Knowledge.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada

- “Renaissance.” English Department. Brooklyn College.

- “Syrup of Violet.” Folger Shakespeare Library. Women’s contributions to science in the Renaissance.

Literature

- “The Spenserian Stanza.” Department of English. Emory University.

The Sonnet

The Pastoral Mode

- “Court Life: Hoping for Reward.” Museum of London.

- “Pastoral.” The UVic Writer’s Guide. Department of English University of Victoria.

- “Queen Elizabeth: Courtship and Love.” Folger Shakespeare Library.

- “The Queen’s Court.” National Maritime Museum.

Drama

- “Blank Verse.” The Poetry Archive.

- “Christopher Marlowe.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “The Elizabethan Theatre.” Hilda D. Spear. University of Dundee. University of Cologne.

- The George Inn video. Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- Globe Theatre video. Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- “Globe Tour.” Clemson Shakespeare Festival. Clemson University.

- “How Do We Know About Shakespeare’s Stage?” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “James Burbage.” Theatredatabase. rpt. from A Dictionary of the Drama. W. Davenport Adams. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1904.

- “The Parts of the Stage.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “Playhouses.” Treasures in Full: Shakespeare in Quarto. British Library.

- “The Plays of the University Wits.” Bartleby.com. Rpt. from The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21). Volume V. The Drama to 1642, Part One.

- “The Rose.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “Shakespeare’s Globe Theater.” Learning Objects Program. Wesleyan University.

- “Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre.” Virtual Tour. Converse: The Literature Website. University of Cambridge.

- “Shakespeare’s Theater.” Folger Shakespeare Library.

- “The University Wits.” Michael Best. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

- “Virtual Tour.” Shakespeare’s Globe. The Shakespeare Globe Trust.

3.2 Sir Philip Sidney (1554–1586)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Define sonnet sequence and apply the term to Sidney’s Astrophil and Stella.

- Characterize Sidney as a courtier poet and identify subject elements of Astrophil and Stella typical of the poetry of a courtier.

- Analyze individual sonnets in Astrophil and Stella to identify English and Petrachan elements in structure and content. Classify individual sonnets as English or Italian.

The epitome of the Elizabethan courtier, the Renaissance man, Sir Philip Sidney was a valiant and recognized soldier, a respected nobleman and statesman, a patron of the arts, and a brilliant writer. He died at age 32 from a wound suffered in battle.

Astrophil and Stella

Sidney’s Astrophil and Stella is an example of a sonnet sequencea group of sonnets exploring all aspects of a topic, a group of sonnets exploring all aspects of a topic. This group of sonnets describes all facets—the good times and bad times, the ups and downs—of the love that “Astrophil” has for “Stella.” Stella means star and Astrophil, star-lover; most scholars believe that the fictional names disguise Sidney himself and the woman he loved, Penelope Devereux, who later married another man, Lord Rich. Notice Sonnet 37 which plays on the word rich.

These sonnets are Petrarchan in content. They follow the convention of the exaggerated lover’s complaint, lamenting his unrequited love for an impossibly beautiful woman. In some of the sonnets, Astrophil is elated because of his love; in others he exhibits despair bordering on a suicidal despondency.

Penshurst, home of Sir Philip Sidney.

Text

Astrophil and Stella may be read on the following websites:

- The Complete Poems of Sir Philip Sidney edited, with memorial introduction and notes by Alexander B. Grosart. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- The Poems of Sir Philip Sidney, ed. with an introduction by John Drinkwater. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- Renascence Editions. An Online Repository of Works Printed in English Between the Years 1477 and 1799. Risa S. Bear. University of Oregon.

- Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- Sir Philip Sidney’s Astrophel & Stella Wherein the Excellence of Sweet Poesy is Concluded, edited from the folio of MDXCVIII. Alfred Pollard. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- Sonnet Central.

Selected Sonnets:

Sonnet 1

Loving in truth, and fain in verse my love to show,

That she, dear she, might take some pleasure of my pain,

Pleasure might cause her read, reading might make her know,

Knowledge might pity win, and pity grace obtain,—

I sought fit words to paint the blackest face of woe;

Studying inventions fine, her wits to entertain,

Oft turning others’ leaves to see if thence would flow

Some fresh and fruitful showers upon my sun-burned brain.

But words came halting forth, wanting invention’s stay;

Invention, nature’s child, fled step-dame Study’s blows,

And others’ feet still seemed but strangers in my way.

Thus, great with child to speak, and helpless in my throes,

Biting my truant pen, beating myself for spite,

Fool, said my muse to me, look in thy heart and write.

This sonnet is the introduction to Sidney’s sonnet sequence Astrophil and Stella. The speaker states that he’s so much in love that he wants to tell his beloved in writing how much he loves her. A point to remember is that in the 16th-century court flirtations and affairs in the courtly love tradition were still common. Although the Sidney and Devereux families at one time considered a marriage, this arrangement did not work out, and in all but the earliest sonnets, Sidney is writing to a married woman. Because this sonnet sequence is in the Petrarchan convention, we expect exaggerated claims about his beloved’s unearthly beauty and how he is dying for love of this woman.

Astrophil studies other people’s writing (“inventions”) and turns pages (“leaves”) of their books, trying to get ideas for his own poem. When he says other “feet” get in his way, he’s talking about poetic meter, poetic feet—another reference to other people’s poetry. He even compares himself to a pregnant woman struggling to give birth to a child; he’s “great with child” trying to give birth to a poem. Finally, his Muse tells him where he should look for his ideas for a poem to Stella—in his own heart.

Sonnet 7

When Nature made her chief work, Stella’s eyes,

In color black why wrapped she beams so bright?

Would she in beamy black, like painter wise,

Frame daintiest luster mixed of shades and light?

Or did she else that sober hue devise

In object best to knit and strength our sight,

Lest, if no veil these brave gleams did disguise,

They, sunlike, should more dazzle than delight?

Or would she her miraculous power show,

That, whereas black seems beauty’s contrary,

She even in black doth make all beauties flow?

Both so, and thus,—she, minding Love should be

Placed ever there, gave him this mourning weed

To honor all their deaths who for her bleed.

This poem is typical Petrarchan praise of the beloved’s beauty, the overly-sentimental love poem content that seems extreme to modern sensibilities. Stella’s eyes are the most beautiful thing in nature. But, he asks, why would nature color something as brilliant as her eyes black? Black is usually the color of mourning. Maybe it’s because her eyes are so dazzling that men would be blinded by them if they weren’t a dark color, Astrophil surmises in a typical Petrarchan exaggeration. (This is the type of content Shakespeare mocks in his Sonnet 130). He finally concludes that nature made her eyes black to mourn all the men that have died for love of Stella.

Sonnet 31

With how sad steps, O Moon, thou climb’st the skies !

How silently, and with how wan a face !

What, may it be that even in heavenly place

That busy archer his sharp arrows tries?

Sure, if that long with love-acquainted eyes

Can judge of love, thou feel’st a lover’s case;

I read it in thy looks; thy languisht grace

To me that feel the like, thy state descries.

Then, even of fellowship, O Moon, tell me,

Is constant love deemed there but want of wit?

Are beauties there as proud as here they be?

Do they above love to be loved, and yet

Those lovers scorn whom that love doth possess?

Do they call virtue there, ungratefulness?

A sonnet sequence records the ups and downs of a love affair. This poem is one of the “downs.” In an apostrophean address to an inanimate object or an abstract quality, an address to an inanimate object or an abstract quality, Astrophil is speaking to the moon, asking if the moon is moving so slowly and is so pale because he (the moon) is love-sick like Astrophil. Has Cupid been shooting the moon with his arrows as he’s been shooting Astrophil? Note the stereotypical marks of being in love that appear in Capellanus’ rules of courtly love.

Note that in the last six lines Astrophil seems a bit sarcastic or bitter. He’s been seen as behaving stupidly (having a “want of wit”) for chasing Stella, and she apparently has scorned him (he says the beautiful women are proud and love to be loved—love the attention they get). Then in the last line he finally tells us what is really annoying him: “Do they call virtue there [in the moon’s realm] ungratefulness?” Apparently Stella has refused his sexual advances, but he thinks that her “virtue” is just “ungratefulness.” In other words, she ought to be so grateful for all the attention he’s showered upon her that she gives in to his sexual advances. And he’s annoyed that she won’t.

Sonnet 39

Come Sleep! O Sleep, the certain knot of peace,

The baiting place of wit, the balm of woe,

The poor man’s wealth, the prisoner’s release,

The indifferent judge between the high and low;

With shield of proof, shield me from out the prease

Of those fierce darts Despair at me doth throw;

O make in me those civil wars to cease;

I will good tribute pay, if thou do so.

Take thou of me smooth pillows, sweetest bed,

A chamber deaf to noise and blind to light,

A rosy garland and a weary head:

And if these things, as being thine by right,

Move not thy heavy grace, thou shalt in me,

Livelier than elsewhere, Stella’s image see.

This sonnet is the low point of the sonnet sequence. While he is annoyed in Sonnet 31, he’s depressed in this one because Stella rejects him. He wishes he could sleep because sleep would be a resting place, a respite from the pain of his unrequited love. Some critics even go so far as to see the poem as a death wish. But, Astrophil says, there is pain even in his sleep because he may dream of Stella.

Sonnet 41

Having this day my horse, my hand, my lance

Guided so well, that I obtained the prize,

Both by the judgment of the English eyes,

And of some sent from that sweet enemy, France;

Horsemen my skill in horsemanship advance,

Townsfolks my strength; a daintier judge applies

His praise to sleight, which from good use doth rise;

Some lucky wits impute it but to chance;

Others, because of both sides I do take

My blood from them who did excel in this,

Think Nature me a man of arms did make.

How far they shot awry! the true cause is,

Stella looked on, and from her heavenly face

Sent forth the beams which made so fair my race.

Astrophil is happy again in this sonnet. He’s won a tournament (the typical knights jousting on horseback). People wonder what enabled him to win: his inherited strength and skill, his fine horsemanship, or maybe he was just lucky. But Astrophil says the reason he won is that Stella was there watching and just the sight of her “heavenly face” inspired him to victory.

Sonnet 49

I on my horse, and Love on me doth try

Our horsemanships, while by strange work I prove

A horseman to my horse, a horse to Love;

And now man’s wrongs in me, poor beast, descry.

The reins wherewith my rider doth me tie,

Are humbled thoughts, which bit of reverence move,

Curb’d in with fear, but with gilt boss above

Of hope, which makes it seem fair to the eye.

The wand is will; thou, fancy, saddle art,

Girt fast by memory, and while I spur

My horse, he spurs with sharp desire my heart:

He sits me fast, however I do stir:

And now hath made me to his hand so right,

That in the manage myself takes delight.

This sonnet is an amusing view of how Astrophil feels about his obsessive love for Stella. Astrophil compares the way he controls his horse to the way his love is controlling him. As you read through the sonnet, you’ll see references to the bit, the reins, the saddle—all the things he uses to control his horse. And his love is controlling him just as thoroughly. And surprisingly enough, he says he loves her so much he doesn’t mind being controlled by his love.

Key Takeaways

- Sir Philip Sidney’s sonnet sequence Astrophil and Stella explores all aspects of its topic, the love of the fictional Astrophil and Stella.

- Although Sidney’s sonnets are Petrarchan in the content of a lover’s lament and exaggerated praise of the beloved’s beauty, the structure features elements of both English and Italian sonnets.

Exercises

- Review the characteristics of Italian and English sonnets. Classify each of the selected sonnets by Sidney Consider both the content and the structure.

- Describe the mood of the lover Astrophil in each of the selected sonnets.

Resources

Background

- Sir Philip Sidney’s Astorphel [sic] and Stella. The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21). Volume III. Renascence and Reformation. XII. The Elizabethan Sonnet. § 6. Bartleby.com.

Text

- The Complete Poems of Sir Philip Sidney edited, with memorial introduction and notes by Alexander B. Grosart. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- The Poems of Sir Philip Sidney, ed. with an introduction by John Drinkwater. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- Renascence Editions. An Online Repository of Works Printed in English Between the Years 1477 and 1799. Risa S. Bear. University of Oregon.

- Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- Sir Philip Sidney’s Astrophel & Stella Wherein the Excellence of Sweet Poesy is Concluded, edited from the folio of MDXCVIII. Alfred Pollard. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- Sonnet Central.

Audio of Astrophil and Stella

- Astrophil and Stella. Read by Elizabeth Klett. LibriVox.

- Audio of Selected Sonnets. Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

Biography

- “Sir Philip Sidney.” Folger Shakespeare Library.

- “Sir Philip Sidney (1554–1586).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

Video

- “Sir Philip Sidney.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

3.3 William Shakespeare (1564–1616)—The Sonnets

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify the English sonnet structure of Shakespeare’s sonnets.

- Recognize vestiges of the Italian sonnet structure in the content of some Shakespearian sonnets.

- Analyze the use of 5 key themes in Shakespeare’s sonnets: time, poetry, beauty, love, and friendship.

Biography

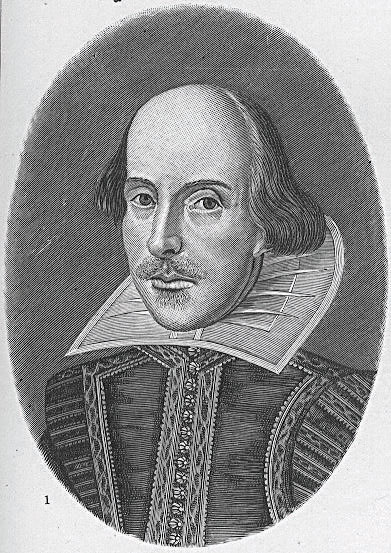

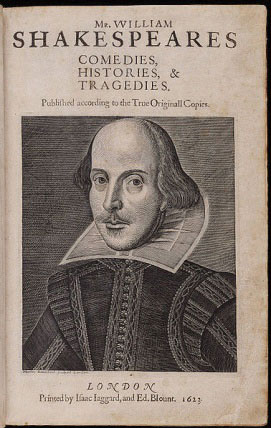

William Shakespeare (1564–1616) is undoubtedly the most well-known and revered name in British literature.

Although entire books of speculation about Shakespeare’s personal life and history abound, little documentary evidence exists. The Folger Shakespeare Library, the British Library, and BBC Historic Figures provide basic biographical information.

His birth, his marriage, the births of his children, and his death are recorded in the parish records of Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon. Also, a few records of business transactions and a few government documents provide enough information for scholars to know that he lived in several places in London, bought a large house in Stratford-upon-Avon, and was involved in some legal proceedings. Shakespeare’s will survives in the National Archives.

Shakespeare’s birthplace in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Shakespeare’s grave in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon.

Text

- Facsimile of The Sonnets Quarto One. The Library of the University of California, Los Angeles. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Toronto.

- Sonnets. Open Source Shakespeare:An Experiment in Literary Technology. George Mason University.

- Shakespeare’s Sonnets by William Shakespeare. Project Gutenberg.

- Sonnets. Electronic Text Center. University of Virginia Library.

The Sonnets

Although Shakespearian sonnets are named for Shakespeare, he was not the first, or the only, person to write sonnets in this form. And not all of his sonnets are entirely English in form. Shakespeare also used elements of the Italian form.

Shakespeare’s sonnets do not constitute a typical sonnet sequence because they do not all address a single topic. By the time Shakespeare was writing his sonnets, the sonnet sequence, usually tracing a love story, had declined in popularity. However, there are five themes that appear throughout all his sonnets: time, poetry, beauty, love, and friendship.

Statue of Shakespeare at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, Stratford-upon Avon.

Some scholars, such Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine, editors of the New Folger Library Shakespeare edition of Shakespeare’s Sonnets, view Shakespeare’s sonnets as autobiographical, referring to “the story that the sequence as a whole seems to tell about Shakespeare’s love life.”

Other critics find that interpretations of Shakespeare’s sonnets often reveal as much or more about the age in which the critiques are written than about the sonnets themselves. Michael Schoenfeldt, for example, writing in The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare’s Poetry (Ed. Patrick Cheney. Cambridge University Press, 2007. Cambridge Collections Online.) asserts that “… the Sonnets have frequently functioned as a mirror in which cultures reveal their own critical presuppositions about the nature of poetic creation and the comparative instabilities of gender, race, and class. Although the Sonnets have proven particularly amenable to some of the central developments of late twentieth-century modes of criticism—particularly feminism and gender and gay studies—they continue to be richer and more complex than anything that can be said about them.”

Although some scholars read Shakespeare’s sonnets as autobiographical, others remind us that in literature the narrative voice should not be assumed to be the author but is instead a persona created by the author. Scholar Helen Vendler, for example, uses the term “fictive speaker” in reference to the speaker of the sonnets (The Art of Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Harvard University Press, 1997).

Key Takeaways

- Shakespeare’s sonnets consistently develop 5 themes: time, poetry, beauty, love, and friendship.

- Shakespeare’s sonnets are English in structure although some sonnets retain elements of the Italian structure.

- Many theories of literary criticism posit that Shakespeare’s sonnets, like most literature, should not be read autobiographically.

Exercises

- In Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29, identify elements that belong to the Petrarchan or Italian tradition. Also locate elements that would characterize the sonnet as an English sonnet.

- In Sonnets 55 and 73, identify the topic of each of the three quatrains. What images are developed in each quatrain? How are these images related? How do the couplets function in these two sonnets?

- In Sonnet 130, how does the speaker address the Petrarchan convention? How does the couplet affect the reader’s perception of the rest of the sonnet?

Resources

Biography

- “Excerpts from Shakespeare’s Will.” Treasures. The National Archives.

- “Shakespeare.” Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon.

- “The Shakespeare Paper Trail: The Early Years.” British History In-depth. BBC.

- “The Shakespeare Paper Trail: The Later Years.” British History In-depth. BBC.

- “Shakespeare’s Biography.” Shakespeare Resource Center.

- “Shakespeare’s Life.” Folger Shakespeare Library.

- “Shakespeare’s Life.” Treasures in Full: Shakespeare in Quarto. British Library.

- William Shakespeare. Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- “William Shakespeare.” Historic Figures. BBC.

Text

- Facsimile of The Sonnets Quarto One 1609 at the Library of the University of California, Los Angeles. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Toronto.

- Open Source Shakespeare: An Experiment in Literary Technology. George Mason University.

- Shakespeare’s Sonnets by William Shakespeare. Project Gutenberg.

- Sonnets. Shakespeare, William, 1564–1616. Electronic Text Center. University of Virginia Library.

Audio

- Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Read by Sir John Gielgud. HarperAudio. Internet Multicasting Service.

- Sonnets. By William Shakespeare. LibriVox.

- Sonnet Central Listening Room.

Video

- “William Shakespeare.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

Images

- “William Shakespeare.” Great Britons: Treasures from the National Portrait Gallery, London.

3.4 Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize characteristics of Senecan tragedy used in Marlowe’s drama.

- Apply the definition of the pastoral mode to Marlowe’s “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love.”

Biography

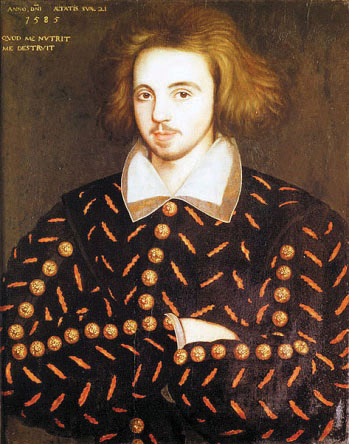

Christopher Marlowe is a good example of an individual caught up in the intrigue and danger of court life who might long to escape to the seemingly simple, leisurely life of the rustic shepherd. Although not born into the nobility, Marlowe attended Cambridge University, then moved to London where he moved in court circles and wrote the plays that secured his fame. He also apparently was engaged in espionage for Elizabeth’s court. At age 29 Marlowe was stabbed to death in an argument over the dinner bill in an inn. Only a week before his death, one of his associates and fellow dramatist, Thomas Kyd, claimed under torture that Marlowe was an atheist, and a warrant was issued for Marlowe’s arrest. This sequence of events has led some historians to believe that Marlowe’s death was staged to help him escape arrest and certain torture. Some have even gone so far as to suggest that Marlowe, in hiding, wrote the plays attributed to Shakespeare although this theory is now considered unlikely.

Portrait believed to be Christopher Marlowe.

Plaque marking the rooms where Christopher Marlowe lived at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge University.

Marlowe’s Plays

The Tragedy of Dido, Queen of Carthage

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

Tamburlaine the Great, Part I

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Renascence Editions. An Online Repository of Works Printed in English Between the Years 1477 and 1799. Risa Stephanie Bear. The University of Oregon.

Tamburlaine the Great, Part II

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Renascence Editions. An Online Repository of Works Printed in English Between the Years 1477 and 1799. Risa Stephanie Bear. The University of Oregon.

The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus

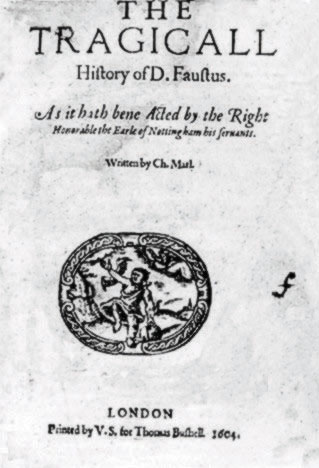

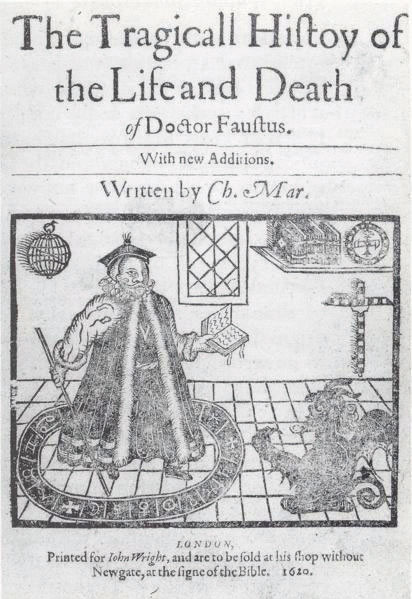

Title page of a late edition of Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus.

- A Text. Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- B Text. Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Renascence Editions. An Online Repository of Works Printed in English Between the Years 1477 and 1799. Risa Stephanie Bear. The University of Oregon.

The Jew of Malta

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text & Image. The University of Pennsylvania Libraries. The Horace Howard Furness Shakespeare Library.

The Tragedy of Edward II

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

The Massacre at Paris

Marlowe’s contemporary and fellow playwright and poet Ben Jonson, in his poem “To the Memory of My Beloved Master William Shakespeare,” coined the phrase “Marlowe’s mighty line” to refer to Marlowe’s use of blank verseunrhymed lines of iambic pentameter, often considered the meter most closely resembling normal English speech, unrhymed lines of iambic pentameter, considered the meter most closely resembling normal English speech. The sonorous lines of blank verse lent themselves to the tragic content of plays such as Tamburlaine and The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus.

In the Renaissance spirit of celebrating and imitating classical art and literature, Marlowe wrote heroic tales in the tradition of the classical Roman dramatist Seneca. Senecan tragedydrama featuring violence, revenge, emotional speeches, and supernatural, usually dark supernatural, elements featured violence, revenge, emotional speeches, and supernatural, usually dark supernatural, elements. Marlowe’s tragedies portray men with aspiring spirits who rise to greatness and then fall, usually through some weakness or flaw in the hero’s own character. Perhaps his most famous character, Dr. Faustus deals with the demon Mephistopheles to sell his soul to the devil to achieve his ambition of power through knowledge only to disappear, presumably to Hell, at the end of the play.

“The Passionate Shepherd to His Love”

Text

- Luminarium. Anniina Jokinen.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

Sidebar 3.1.

Come live with me and be my love,

And we will all the pleasures prove

That hills and vallies, dales and fields,

Woods or steepy mountain yields.

And we will sit upon the rocks,

Seeing the shepherds feed their flocks

By shallow rivers to whose falls

Melodious birds sing madrigals.

And I will make thee beds of roses

And a thousand fragrant posies,

A cup of flowers and a kirtle

Embroidered all with leaves of myrtle.

A gown made of the finest wool

Which from our pretty lambs we pull;

Fair-linèd slippers for the cold,

With buckles of the purest gold.

A belt of straw and ivy-buds,

With coral clasps and amber studs;

An if these pleasures may thee move,

Come live with me, and be my love.

The shepherd-swains shall dance and sing

For thy delight each May-morning:

If these delights thy mind may move,

Then live with me, and be my love.

Christopher Marlowe’s “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love” is one of the most well-known examples of pastoral poetry, a type of literature that portrays shepherds in an idealized rural setting, engaging in contests of singing or poetry, flirting with country maidens, watching their flocks in a peaceful and beautiful natural world. Most of the people who wrote pastoral poetry were, however, men of the court who had only a “fairy tale” view of a shepherd’s life. They imagined shepherds sitting in the meadows watching their sheep while singing songs and flirting with the shepherdesses. They had little idea of the hard lives led by the peasants. Marlowe’s reference to “pulling” the wool off the sheep, for example, demonstrates that he had little real knowledge of sheep herding, and his mistaken belief that a shepherd would have gold for his lady’s buckles indicates that his life was far removed from that of a poor shepherd.

Exercises

- In Marlowe’s poem, what does the shepherd offer to entice his love to live with him?

- How do these enticements fit into the pastoral convention?

Resources

Biography

- “Christopher Marlowe.” Theatre History.com. rpt. from Elizabethan and Stuart Plays. Ed. Charles Read Baskerville. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1934. 307–308.

- “Christopher Marlowe’s Canterbury Childhood.” Theatre History.com. rpt. from Christopher Marlowe and His Associates. John H. Ingram. London: Grant Richards, 1904.

- “The Life and Work of Christopher Marlowe.” Theatre History.com. rpt. from Christopher Marlowe. William Lyon Phelps. New York: American Book Company, 1912.

- Luminarium. Anniina Jokinen. rpt. from Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Ed. Vol XVII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910. 744.

- “Marlowe Timeline.” OpenLearn. The Open University.

Play Texts

The Tragedy of Dido, Queen of Carthage

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

Tamburlaine the Great, Part I

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Renascence Editions. An Online Repository of Works Printed in English Between the Years 1477 and 1799. Risa Stephanie Bear. The University of Oregon.

Tamburlaine the Great, Part II

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Renascence Editions. An Online Repository of Works Printed in English Between the Years 1477 and 1799. Risa Stephanie Bear. The University of Oregon.

The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus

- A Text. Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- B Text. Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Renascence Editions. An Online Repository of Works Printed in English Between the Years 1477 and 1799. Risa Stephanie Bear. The University of Oregon.

The Jew of Malta

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

- Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text & Image. The University of Pennsylvania Libraries. The Horace Howard Furness Shakespeare Library.

The Tragedy of Edward II

- Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Gregory R. Crane, editor.

- Project Gutenberg.

The Massacre at Paris

Text “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love”

- Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- Luminarium. Anniina Jokinen.

- Project Gutenberg.

The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus

- “Christopher Marlowe, Doctor Faustus.” Dr Anita Pacheco. Learning Space. The Open University. course materials from The Open University course.

Audio

- “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love.” Eaglesweb.com. Audio Anthology of Lyrical Poetry in Modern English. Recorded by Walter Rufus Eagles.

Selections from Librivox

- Marlowe, Christopher. “Doctor Faustus (closing lines)” (in “Poems Recorded in Deptford and Greenwich”).

- Marlowe, Christopher. “Hero and Leander.”

- Marlowe, Christopher. “Jew of Malta, The.”

- Marlowe, Christopher. “Passionate Shepherd to His Love” (in “Short Poetry Collection 061”) Marlowe, Christopher. “Passionate Shepherd to his Love, The” (in “Wedding Poems”).

- Marlowe, Christopher. “Passionate Shepherd to His Love, The” (in “Romantic Poetry Collection 001”).

- Marlowe, Christopher. “Passionate Shepherd to His Love, The” (in “Short Poetry Collection 088”).

- Marlowe, Christopher. “Tragical History of Doctor Faustus, The.”

Works in Progress From LibriVox

3.5 Sir Walter Ralegh (1552–1618)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Analyze the Nymph’s response to the elements of the pastoral mode in “The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd.”

“The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd”

One of many replies to Marlowe’s “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love” is “The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd” written by Sir Walter Ralegh. Rather than the idealistic view of life seen in Marlowe’s poem, Ralegh’s reply concentrates on the transitory nature of earthly joys. When considered in the light of Ralegh’s biography, the poem’s bitterness seems to reflect the author’s own experiences. Although Ralegh was for a time a great favorite of Queen Elizabeth and a renowned, successful explorer of the New World, establishing the Roanoke Colony, he fell from favor when he married one of the Queen’s ladies-in-waiting without the Queen’s permission. After the death of Elizabeth I and the succession of James I, Ralegh’s influence in court fell. Disillusioned and angered by his declining status and resultant financial difficulties, he apparently took part in a failed conspiracy against the King and was imprisoned in the Tower of London. A letter written to his wife before his execution reveals Ralegh’s bitterness about his fate.

Text

- “The Nymph’s Reply.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English. University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

Sidebar 3.2.

If all the world and love were young,

And truth in every shepherd’s tongue,

These pretty pleasures might me move

To live with thee and be thy love.

Time drives the flocks from field to fold,

When rivers rage and rocks grow cold;

And Philomel becometh dumb;

The rest complains of cares to come.

The flowers do fade, and wanton fields

To wayward winter reckoning yields:

A honey tongue, a heart of gall,

Is fancy’s spring, but sorrow’s fall.

The gowns, thy shoes, thy beds of roses,

Thy cap, thy kirtle, and thy posies

Soon break, soon wither, soon forgotten,—

In folly ripe, in reason rotten.

Thy belt of straw and ivy buds,

Thy coral clasps and amber studs,

All these in me no means can move

To come to thee and be thy love.

But could youth last and love still breed,

Had joys no date nor age no need,

Then these delights my mind might move

To live with thee and be thy love.

Sidebar 3.3.

Sir Walter Raleigh is perhaps best known to Americans as one of the first to attempt to colonize the New World. The colony he established in Virginia (named for Elizabeth I, the Virgin Queen) has become known as the lost colony of Roanoke. Raleigh and a group of the settlers returned to England for supplies, and when the settlers, without Raleigh, returned the entire colony had disappeared. He is also well known for a story, unlikely to be true, that when Queen Elizabeth visited his ship, he threw his cloak over a mud puddle so that she would not have to get her shoes wet or muddy, a gesture more impressive when one considers the cost of the materials needed to make a gentleman’s cloak in the 16th century. He’s also known for introducing tobacco to England.

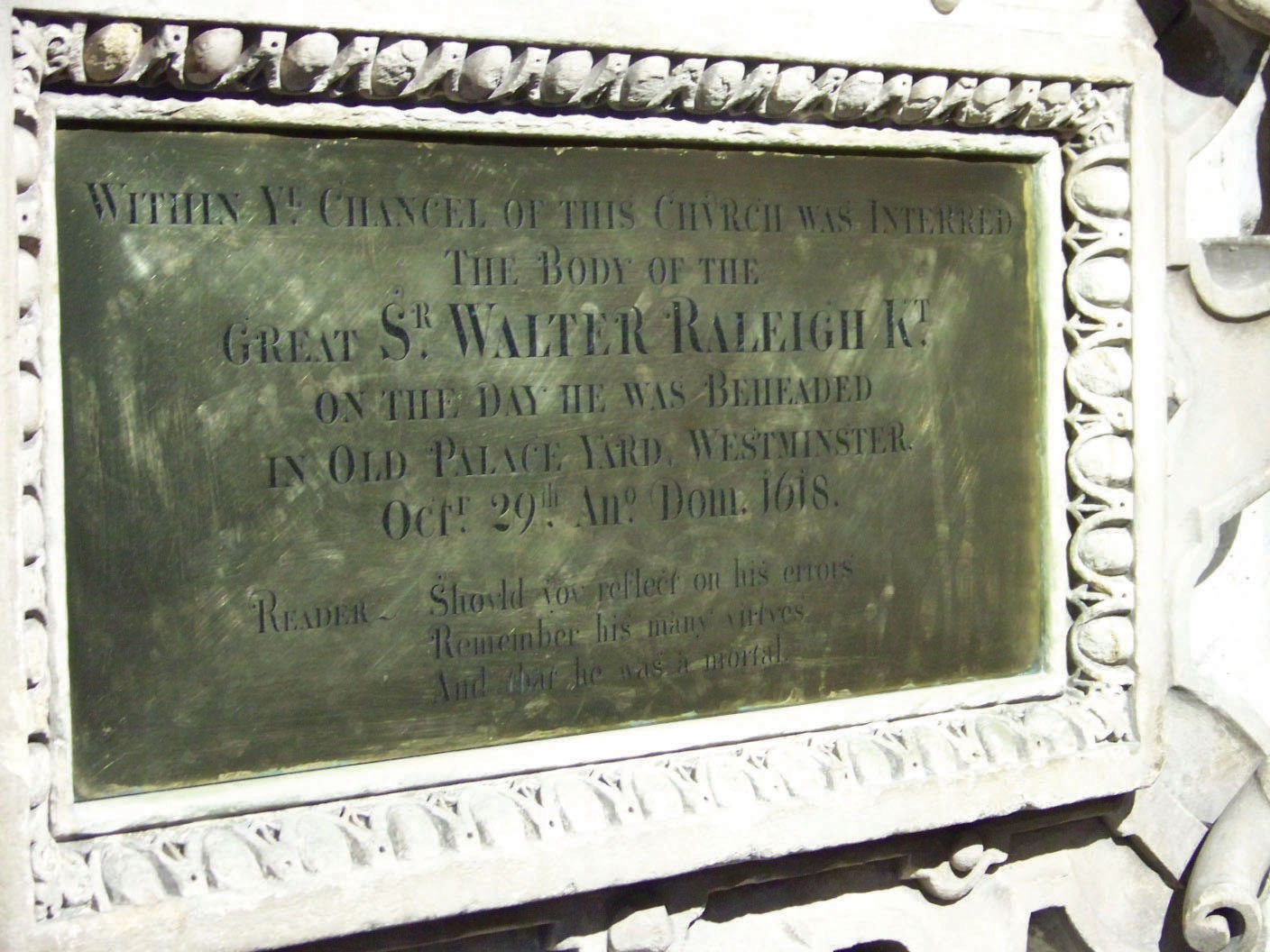

Imprisoned when the Queen discovered he had married one of her ladies-in-waiting without her permission, Raleigh was eventually released although he remained out of favor with the Queen for many years. After Elizabeth I’s death, Raleigh was again imprisoned in the Tower of London, accused of plotting against the new King James I. Although he was sentenced to death, the sentence was not carried out, and Raleigh eventually was released to lead another expedition in search of riches in the New World. During this expedition, his troops attacked a Spanish settlement, and the Spanish demanded that King James I carry out the death sentence earlier imposed. Raleigh was beheaded and buried in St. Margaret’s Church.

Figure 3.4

Figure 3.4. shows the room in the Tower of London in which Raleigh was imprisoned. Wealthy prisoners often lived in relative comfort while in captivity. Their families and friends were allowed to purchase food, fuel for heat, and other comforts for the prisoners. Here Ralegh began to write A History of the World, a work which he never finished.

Figure 3.5

Figure 3.5. shows the stained glass window in St. Margaret’s church which commemorates Sir Walter Raleigh as one of Elizabeth I’s favorites. Raleigh is the figure to the left of Elizabeth I in the center.

Figure 3.6

The plaque in Figure 3.6. states that Sir Walter Raleigh is interred in St. Margaret’s Church.

Key Takeaway

- Sir Walter Raleigh’s reply to Marlowe’s “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love” emphasizes the transitory nature of pastoral pleasures.

Exercises

- Compare the content of Marlowe’s “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love” and Raleigh’s “The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd.” What specific natural items referred to in Marlowe’s poem does the Nymph mention?

- How does the young woman (the “nymph”) in Raleigh’s poem answer the shepherd? What is her reasoning for her answer?

- How would you characterize the tone of the Nymph’s reply?

Resources: Walter Raleigh

Biography

- “Sir Walter Ralegh (1562–1618). Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- Walter Raleigh. Historic Figures. BBC.

- “Letter: Sir Walter Raleigh Bids Farewell to His Wife a Few Hours Before He Expects to be Executed.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

Text

- “The Nymph’s Reply.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

Audio

- “The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd.” Eaglesweb.com Audio Anthology of Lyrical Poetry in Modern English. Recorded by Walter Rufus Eagles.

- “The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd.” LibriVox.

3.6 Elizabeth I (1533–1603)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify the political and literary achievements of Elizabeth I.

- Recognize the influence of 16th-century religious turmoil on the literature of the time.

Biography

Daughter of Henry VIII and his second wife Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth became queen only after the deaths of her younger brother Edward VI and her older sister Mary I. Leading England to an unprecedented position of world power and influence, Elizabeth gave her name to the age while encouraging trade, exploration, and the arts, including Shakespeare. This portrait of Elizabeth by George Gower (1540–1596) is known as the Armada portrait, picturing Elizabeth after the defeat of the Spanish Armada, at the height of her and her country’s power. The defeated Armada can be seen in the upper left, a crown below signifying Elizabeth’s royal power, her hand resting on a globe indicating England’s world dominance. Even the sumptuous costume, jewels, and surroundings evoke the glories of Elizabeth and her court. In addition to being a patron of the arts, Elizabeth I was a poet and musician.

“Written on a Wall at Woodstock”

When her half-sister Mary Tudor ascended the throne as Mary I, Elizabeth, age 21, was imprisoned in the Tower of London and for a time at Woodstock Manor. Mary I and her advisors feared that the Princess Elizabeth would be a rallying point for Protestants who wanted to replace the Roman Catholic Mary. Confined in the Woodstock Manor Gatehouse, Elizabeth wrote verses expressing her frustration at her fate.

Text

- Luminarium. Anniina Jokinen.

- Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

Written on a Wall at Woodstock

By Princess Elizabeth (later Elizabeth I)

O FORTUNE! how thy restless wavering State

Hath fraught with Cares my troubled Wit!

Witness this present Prison whither Fate

Hath borne me, and the Joys I quit.

Thou causedest the Guilty to be loosed

From Bands, wherewith are Innocents inclosed;

Causing the Guiltless to be strait reserved,

And freeing those that Death had well deserved:

But by her Envy can be nothing wrought,

So God send to my Foes all they have thought.

ELIZABETH PRISONER.

A.D. M.D.LV.

“The Doubt of Future Foes”

Later as Queen, Elizabeth again expressed her fears and frustration at being surrounded by those who would seek to influence her or even to replace her on the throne, particularly her cousin Mary Queen of Scots, the “daughter of debate” referred to in the poem. Like Elizabeth’s half-sister Mary Tudor, Mary Queen of Scots was Roman Catholic, and after the death of Mary Tudor she became a rallying point for those who wanted a Catholic monarch. Just as Mary Tudor had Elizabeth imprisoned, Elizabeth ordered the imprisonment of Mary Queen of Scots. While Mary Tudor had stopped short of having Elizabeth executed, Elizabeth eventually was persuaded to order Mary Queen of Scots beheaded.

Text

- Luminarium. Anniina Jokinen. text and audio.

- Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

The Doubt of Future Foes

By Elizabeth I, Queen of England

The doubt of future foes exiles my present joy,

And wit me warns to shun such snares as threaten mine annoy;

For falsehood now doth flow, and subjects’ faith doth ebb,

Which should not be if reason ruled or wisdom weaved the web.

But clouds of joys untried do cloak aspiring minds,

Which turn to rain of late repent by changèd course of winds.

The top of hope supposed, the root of rue shall be,

And fruitless all their grafted guile, as shortly ye shall see.

The dazzled eyes with pride, which great ambition blinds,

Shall be unsealed by worthy wights whose foresight falsehood finds.

The daughter of debate that discord aye doth sow

Shall reap no gain where former rule still peace hath taught to know.

No foreign banished wight shall anchor in this port;

Our realm brooks not seditious sects, let them elsewhere resort.

My rusty sword through rest shall first his edge employ

To poll their tops that seek such change or gape for future joy.

“Speech to the Troops at Tilbury”

One of the highlights of Elizabeth’s reign was the defeat of the Spanish Armada, a victory which established England as a world power. The following speech purportedly was given by Elizabeth to her troops gathered at Tilbury to repel the Spanish troops that succeeded in getting through the English navy and invading England itself. These land troops, however, were never needed because of the success of the English navy. Whether Elizabeth actually delivered this speech, including the famous line “I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too…,” or whether it was composed later and circulated as a means of reinforcing Elizabeth’s reputation and the importance of the battle in the minds of the people, no one is sure.

Text

- Luminarium. Anniina Jokinen. text and audio.

- “Queen Elizabeth I: Against the Spanish Armada, 1588.” Modern History Sourcebook. Paul Halsall. Fordham University.

Speech to the Troops at Tilbury

My loving people,

We have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit our selves to armed multitudes, for fear of treachery; but I assure you I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people. Let tyrants fear, I have always so behaved myself that, under God, I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and good-will of my subjects; and therefore I am come amongst you, as you see, at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of the battle, to live and die amongst you all; to lay down for my God, and for my kingdom, and my people, my honour and my blood, even in the dust. I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm; to which rather than any dishonour shall grow by me, I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field. I know already, for your forwardness you have deserved rewards and crowns; and We do assure you in the word of a prince, they shall be duly paid you. In the mean time, my lieutenant general shall be in my stead, than whom never prince commanded a more noble or worthy subject; not doubting but by your obedience to my general, by your concord in the camp, and your valour in the field, we shall shortly have a famous victory over those enemies of my God, of my kingdom, and of my people.

Key Takeaway

- In an age in which few women wrote literature, particularly literature that survives, Elizabeth I, because of her royal birth, is an exception in education and social acceptance of activities not usually considered suitable for women.

Exercises

- In “Written on a Wall at Woodstock” Elizabeth I addresses fortune, an example of the literary technique apostrophe, an address to an inanimate object or an abstract quality. What specific events does she ascribe to fortune? What fate does she request that God send her foes?

- How does the tone of “Written on a Wall at Woodstock” compare with that of “The Doubt of Future Foes”? How do the circumstances in which the two poems were written compare?

- How would you evaluate “Speech to the Troops at Tilbury” as a public relations tool?

- What does Elizabeth mean when she says, “I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.…” Why would it be important for her to include this remark?

Resources

Biography

- “Elizabeth (1533–1603).” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium.

- Elizabeth I. Historic Figures. BBC.

- “Woodstock Manor.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt. from Paul Hentzner. A Journey Into England, (1598). Horace Walpole, ed. 1757. Fugitive Pieces on Various Subjects. Vol II. Robert Dodsley, ed. London: J. Dodsley, 1771. 258.

Texts

“Written on a Wall at Woodstock”

- Luminarium. Anniina Jokinen.

- Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

“The Doubt of Future Foes”

- Luminarium. Anniina Jokinen. text and audio.

- Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

“Speech to the Troops at Tilbury”

- Luminarium. Anniina Jokinen. text and audio.

- “Queen Elizabeth I: Against the Spanish Armada, 1588.” Modern History Sourcebook. Paul Halsall. Fordham University.

Audio

“The Doubt of Future Foes”

- Luminarium. Anniina Jokinen. text and audio.

“Speech to the Troops at Tilbury”

- Luminarium. Anniina Jokinen. text and audio.

3.7 William Shakespeare (1564–1616)—The Plays

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Comprehend the significance of Renaissance drama in the history of the theater.

- Understand Elizabethan era printing.

Just as the Elizabethan period is called a Golden Age in British history, the time period in which Shakespeare wrote, acted, and produced plays is a Golden Age of British, and even world, drama. Ironically, hard on the heels of this flowering of Elizabethan drama, the Puritans shut down the theatres in England during the English Civil War. Thus, a dearth of drama quickly followed the wealth of Shakespeare’s time period.

None of Shakespeare’s plays exists in manuscript format. Instead, Shakespeare’s plays have come to us through early published copies, some of which were inaccurately recorded by actors or others who thought to profit by publishing their own copies of the popular plays. During the 16th century, copyrights as we know them didn’t exist. The Stationers’ Company, a city guild for printers and book sellers, controlled what was printed, thus providing a means of government censorship. The Folger Shakespeare Library provides a video explaining Renaissance printing techniques.

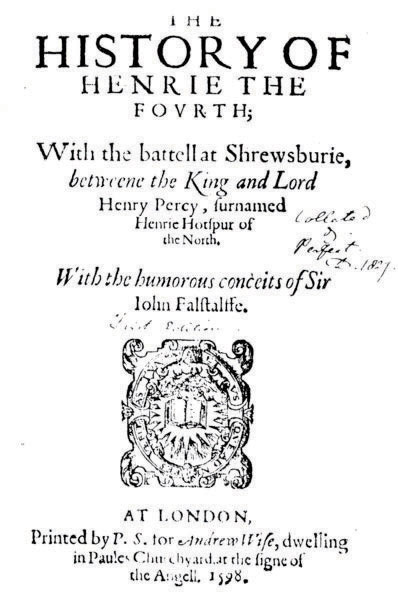

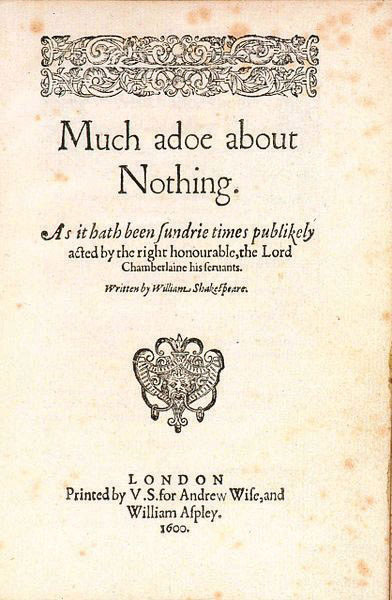

Many of the early publications were in quartoa sheet of paper folded into quarters, creating 4 leaves (8 pages), a sheet of paper folded into quarters, creating 4 leaves (8 pages). The British Library and The Shakespeare Quartos Archive provide digital images of all the plays published in quarto.

A folioa sheet of paper folded in half, forming a larger sized book was the same piece of paper folded in half, forming a larger sized book. In 1623, the First Foliothe first complete collection of Shakespeare’s plays, the first complete collection of Shakespeare’s plays, was compiled and published by John Hemminge and Henry Condell, two of Shakespeare’s fellow actors. Digital images of Shakespeare’s First Folio are available from the Folger Shakespeare Library, the Perseus Digital Library, and from the Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text and Image, Furness Collection.

Shakespeare’s plays are generally divided into three categories: tragedies, comedies, and history plays, a division first seen in the First Folio. George Mason University’s Open Source Shakespeare lists the plays by genre.

Text

- The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Open Source Shakespeare: An Experiment in Literary Technology. George Mason University.

- Project Gutenberg.

Key Takeaways

- Renaissance drama is a highlight in the history of the English theatre.

- The First Folio, compiled after Shakespeare’s death, is the first complete collection of Shakespeare’s plays.

Exercises

- What are some ways in which the limitations of a 16th-century theatre, such as the Globe, would have affected the production of Shakespeare’s plays?

- What purposes did the Stationers’ Company serve? How does it differ from modern copyright laws?

- What difficulties would you imagine are encountered by modern editors because Shakespeare’s original manuscripts do not exist?

Resources

Background

- “London Book Trade.” Treasures in Full: Shakespeare in Quarto. British Library.

- Multi-Media Tutorials.The English Renaissance in Context. Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text and Image. Furness Collection. University of Pennsylvania Library.

- Open Source Shakespeare: An Experiment in Literary Technology. George Mason University. concordance, character search, keyword search, plays by genre, plays by date.

- “Publishers, Players, and Planning.” Treasures in Full: Shakespeare in Quarto. British Library.

- “Renaissance Printing 101.” Folger Shakespeare Library.

- Treasures in Full: Shakespeare in Quarto. British Library.

Text

- The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Open Shakespeare. Open Knowledge Foundation.

- Open Source Shakespeare: An Experiment in Literary Technology. George Mason University.

- Project Gutenberg.

First Folio and Quartos

- First Folio. Perseus Digital Library. digital images of the First Folio.

- First Folio. Rare Book Room. digital images of the First Folio.

- “The First Folio of Shakespeare.” Folger Shakespeare Library. information about the First Folio and image of the title page.

- The Horace Howard Furness Shakespeare Library. First Folio. Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text and Image. The University of Pennsylvania Libraries.

- “The Quartos of Shakespeare.” Rare Book Room. digital images of the quartos.

- The Shakespeare Quartos Archive.

- Treasures in Full: Shakespeare in Quarto. British Library. digital images of all of Shakespeare’s plays published in quarto.

Background Information on the Plays

- “The Plays.” Folger Shakespeare Library. Background information about each play and image of first page of quarto or folio publication.

- “The World of Shakespeare: A Research Guide.” J. Eugene Smith Library. Eastern Connecticut State University.

Audio

Video

- Folger Shakespeare Library YouTube channel.

- Shakespeare After All: The Later Plays. Dr. Marjorie Garber. Harvard Open Learning Initiative.

- Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre. Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- Shakespeare’s I Henry IV: Henry Hotspur Percy. Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

3.8 I Henry IV

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Categorize Shakespeare’s I Henry IV as a history play.

- Understand the actual history behind the conflicts portrayed in I Henry IV, recognize historical elements Shakespeare fictionalized, and explain the reasons for those changes.

- Trace the development of the character of Prince Hal.

- Analyze Shakespeare’s use of structure to reflect character, including the evolving character of Prince Hal.

- Identify major characters.

I Henry IV falls into the category of history plays. Elizabeth I was a direct descendent of Henry IV and Prince Hal (Henry V); therefore, the plays which glorified her ancestors were quite popular with the Queen and her court. Shakespeare apparently realized the advantages of taking dramatic liberties with historical facts, sometimes to improve the story and sometimes to please the Queen.

I Henry IV was entered in the Stationers’ Register on February 25, 1598 and published in the First Quarto in 1598. Additional printings followed frequently, attesting to the popularity of the play.

The Folger Shakespeare Library presents a brief video introduction, I Henry IV Insider’s Guide, which features actors for its production of the play discussing plot and character.

Plot

Shakespeare’s basic historical plot was likely taken from Holinshed’s Chronicles; however, Shakespeare took dramatic liberties with the timing of events. In I Henry IV, Shakespeare presents the Percies’ revolt in 1403, Archbishop Scroop’s rebellion in 1405, and Northumberland’s and the Welsh uprising in 1408 as if they occurred together in order to create a coherent plot. In another departure from historical fact, Shakespeare makes Hotspur the contemporary of Hal, thus allowing the audience to contrast the two. The historical Hotspur was closer in age to Hal’s father.

Shakespeare’s history plays Richard II, I Henry IV, II Henry IV, Henry V, Henry VI Parts I, II, and III, and Richard III, present the dynastic struggles between two branches of the royal family known as the Wars of the Roses.

William Shakespeare and the Wars of the Roses

Throughout the last fifty years of the Middle Ages, England was embroiled in civil strife between two branches of the royal Plantagenet family, the Lancasters and the Yorks. Because the emblem of the Lancasters was the red rose and the emblem of the Yorks was the white rose, these battles were referred to as the Wars of the Roses. Although the Wars of the Roses are usually dated from around 1450 until 1485, the struggle stretched all the way back to the reign of Edward III which ended with his death in 1377 (during the time Chaucer was writing).

The tomb of Edward the Black Prince in Canterbury Cathedral.

The death of Edward III’s oldest son, known as Edward the Black Prince, resulted in conflict between supporters of Richard (Edward III’s grandson and Edward the Black Prince’s son) and supporters of his third son John of Gaunt (Chaucer’s patron) and his descendents (the house of Lancaster). Richard did become King Richard II, but died under mysterious circumstances while imprisoned by his cousin Henry who then became King Henry IV.

In the late 16th century, Shakespeare wrote a series of history plays which chronicled the Wars of the Roses:

| Edward III (attributed to Shakespeare by some scholars) | 1596 |

| Richard II | 1595 |

| Henry IV, Part 1 | 1596–1597 |

| Henry IV, Part 2 | 1597–1598 |

| Henry V | 1598–1599 |

| Henry VI, Part 1 | 1590–1591 |

| Henry VI, Part 2 | 1590–1591 |

| Henry VI, Part 3 | 1591–1592 |

| Richard III | 1592–1593 |

Edward III

Edward III was a politically and militarily strong king who had 4 sons, all of whom had the strong personality and leadership abilities of their father. Had the oldest son, Edward the Black Prince, lived, the Wars of the Roses might never have taken place; the throne would without question have passed to Edward. Edward the Black Prince, however, died before his father, leaving his 10-year-old son Richard as his heir.

During the 14th century, a king still had to be a warrior to hold on to his throne; an important part of a king’s job was holding territory against invaders. A boy-king was dependent on his “protectors” to fight his battles for him and to ward off usurpers until he could physically protect himself and his domain.

When King Edward III died, many people felt that the crown should pass not to his 10-year-old grandson Richard, but to one of his other sons, John Duke of Lancaster (red rose) or Edmund Duke of York (white rose). John and Edmund agreed! (Lionel, the second son, had also died, but his descendents were the Nevilles, who by marriage figured prominently in the future royal line.)

The battle for the crown had begun.

Richard II

The grandson Richard was crowned but proved to be a weak, unpopular king. His cousin Henry, son of John Duke of Lancaster, felt that he would be a much better king and that his father really should have been king anyway. Henry staged a rebellion against Richard, captured him, and Richard soon “died” in prison. Henry declared himself King Henry IV.

Henry IV

Henry IV was a strong king who put down 4 separate rebellions led by people who had supported Richard II.

Henry V

Henry V was one of the best of English kings. He recaptured parts of France and sealed the bargain by marrying Katherine, daughter of the French king. England probably could have peacefully united behind Henry V, ending the dynastic conflict. Unfortunately, Henry V died, leaving his infant son Henry as his heir.

Henry VI

Henry VI grew up to be a weak leader, a scholarly, religious man who really wanted to be a priest, not a king. He ignored affairs of state in favor of solitary study and worship. He lost all the lands in France won by his father, and his cousin, Richard Duke of York, soon started a military campaign to overthrow the Lancastrian King Henry VI. Richard and one of his sons were captured and executed by Henry’s armies, their heads posted on stakes over Micklegate Bar in the city of York. The surviving sons Edward, George, and Richard continued their father’s battle with the substantial help of another cousin, Richard Neville (known as Warwick the Kingmaker). Henry VI’s troops were defeated, and he was imprisoned in the Tower of London where he “died” during Edward’s reign.

Edward IV

With Henry VI in prison, Edward was crowned King Edward IV. He was a young, tall, handsome man with strong military and political skills, and the English people generally welcomed his leadership. Since Henry VI’s only son Edmund (son of Margaret and husband of Anne Neville in Richard III) had been killed in battle, he had the strongest claim to the throne. Both his mother and his father were descendents of Edward III. But again, the death of the father before his sons were of age plunged the country into another war of the red rose of Lancaster and white rose of York. Before he died, Edward IV named his younger brother Richard “protector” of his heir.

Edward V

The 12-year-old son of Edward IV was never officially crowned but is referred to as Edward V. His uncle Richard had him taken to the Tower of London for security reasons, and young Edward V was never seen again. No one knows when or how he and his younger brother Richard died.

Richard III

With all the Lancastrian claimants to the throne dead and all his older Yorkist brothers dead as well, Richard became king. He was soon challenged, however, by Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond. Henry Tudor had the weakest of claims to the throne. He was a descendent of John of Gaunt and his second wife (who had first been his mistress) and of the wife of Henry V and her second husband, Owen Tudor, a Welsh commoner.

Henry VII

Henry Tudor defeated Richard III in battle at Bosworth Field and was crowned King Henry VII. He married Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV. With his Lancastrian blood and her Yorkist blood, their descendents thus united the two warring factions of the family and established the Tudor dynasty. Their son Henry VIII and his daughter Elizabeth I were two of England’s strongest monarchs.

“The rose both white and rede

In one rose now doth growe”

The Wars of the Roses.

Structure and Theme

Shakespeare’s use of a comic element, the character Falstaff and the subplot involving his exploits, as a central feature of the play is an important development in the history play as a dramatic form. Falstaff is a miles gloriosusthe braggart solider, a stock character in classical Roman comedy—the braggart solider, a stock character in classical Roman comedy—and is often considered Shakespeare’s greatest comic character.

Statue of Falstaff in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Statue of Prince Hal in Stratford-upon-Avon.