This is “The Twentieth Century”, chapter 8 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 8 The Twentieth Century

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

8.1 The Twentieth Century

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize characteristics of Modernism in literature.

- Define postcolonial literature.

- Describe postmodern literature.

- Assess the role of English as a global language in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

London in the 1930s.

The Edwardian Age

The death of Queen Victoria in 1901 and the accession of Edward VII inaugurated not only a new century but a new milieu in art, an extension and development of the aestheticism that characterized the last decade of the 19th century. The Edwardian Age and the Modern Period which followed, roughly from 1910 through the end of World War II, differed sharply from the preceding age.

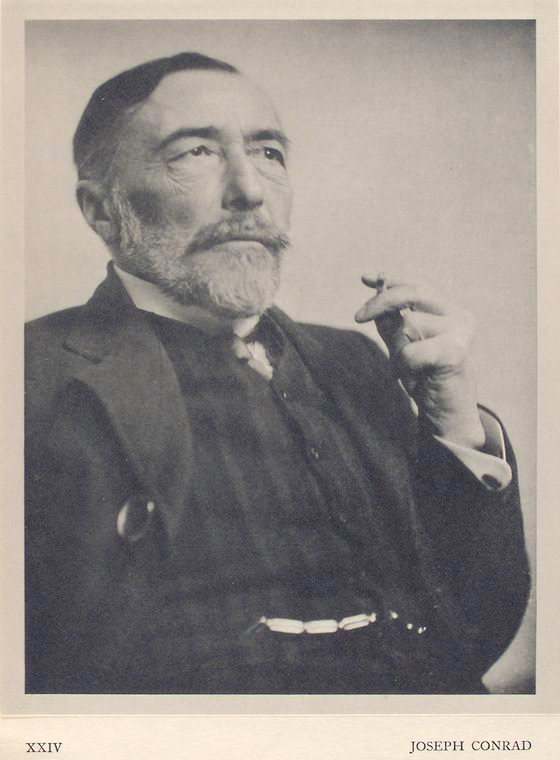

The elegance and extravagance of the aristocracy, led by King Edward VII, continued unchecked until World War I. However, underneath the ostentation so loved by the King sounded ominous warnings of unrest throughout Britain and the European continent. At the death of Edward VII in 1910, the British Empire also was dying as imperialism came under increasing criticism. Events such as the Boer War exposed the consequences of empire-building, and authors such as Joseph Conrad vividly portrayed for the British public a picture contrasting the supposed glory of empire. Even Edward VII himself criticized the British presence in India and the treatment of the country’s inhabitants.

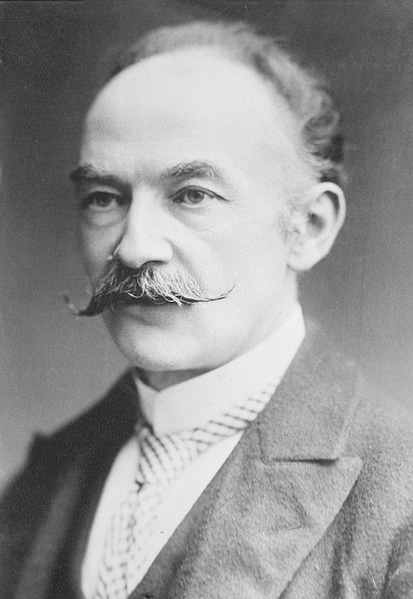

Poet Thomas Hardy, often referred to as the great pessimist, depicted the new century as a time of uncertainty and disbelief, both in God and in the integrity of humankind. Cynicism and pessimism replaced Victorian optimism and confidence. Although science and technology continued their ever more rapid advancement with electricity, telegraph and radio, continued mechanization in workplaces, automobiles, and airplanes, society seemed to lack a solid center of reference, a core belief that held the uncertainties of life in check and gave life a sense of purpose and direction.

Hardy and Joseph Conrad bridge the 19th and 20th centuries, both in time and in the philosophy of their writing.

The Modern Age

World War I

King George V followed his father Edward VII to the throne in 1910 and reigned until 1936. Only four years after he became king, George V led his country through World War I, fighting against his first cousin Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany, both men descendants of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Czar Nicholas II of Russia, overthrown and executed with his wife and family in 1917, was also King George’s cousin by marriage, his wife Alexandra another descendent of Victoria and Albert, whose children had married into most of the royal families in Europe.

George V by Sir Luke Fildes.

Essentially an entire generation of British men—and many women—were killed in World War I. Others returned maimed, physically and mentally. War poets such as Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owens vividly depicted the horror of war, the reality of war as compared to the slogans and imagined glory of fighting for one’s country. The economic cost of the war also devastated Britain. The conspicuous wealth of the Edwardian Era disappeared into a financial depression.

Irish nationalism brought added tension to Britain. The desire for home rule in Ireland, then part of the British Empire, culminating in the Easter Uprising of 1916, caused strife and instability on another front for Britain. Fears that Ireland would collaborate with Germany in World War I led to British concessions and, after the war, the granting of Irish independence in 1922. William Butler Yeats commemorated and contributed to Irish patriotism in his writing.

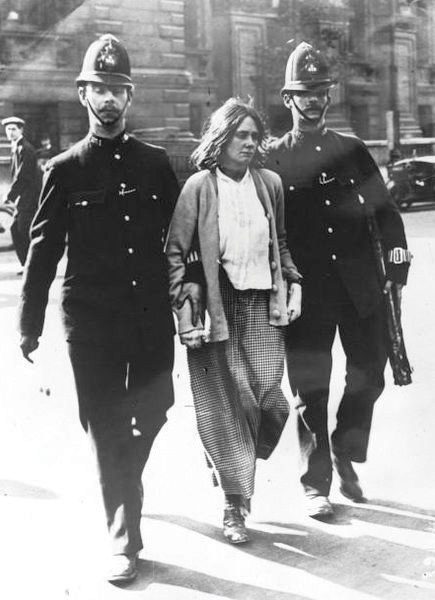

Arrest of a Suffragette, 1914.

The active role of women in the war effort helped achieve universal suffrage in 1928.

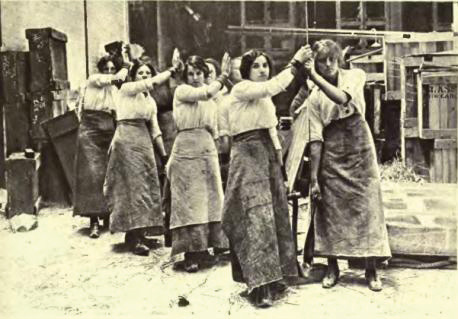

Women working in the absence of men during World War I.

By the end of World War I, Britain was a much different place from the exuberant, confident empire that Victoria knew.

World War II

The oldest son of George V, Edward, in his role of Prince of Wales and heir apparent was not allowed to participate in combat during World War I, but his efforts to visit and encourage areas suffering from depressed economic times in the 1930s made him a popular figure among the British. After the death of his father, Edward became King Edward VIII; however, within a year he made the government aware that he wished to marry the twice-divorced American woman Wallace Simpson. Because of the monarch’s role as head of the Church of England, political leaders and advisors in Britain opposed the marriage. Edward VIII chose to abdicate the throne in order to marry Simpson. Upon his abdication, his younger brother became King George VI. With his wife and queen, the Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, George VI symbolized the courage, fortitude, and the “stiff upper lip” with which the country endured the hardships of World War II. The couple and their children, the current Queen Elizabeth II and her younger sister the late Princess Margaret, spent the war years at Buckingham Palace and in Windsor rather than evacuate to safer areas. The royal family’s determination to share in the hardships and dangers of the war earned the admiration of the British public.

Modern Literature

In Thomas Hardy’s novel Tess of the d’Urbervilles, the ill-fated girl Tess has a conversation with her brother in which he remembers that she has told him the stars are other worlds. When he asks if all the star-worlds are like their world, Tess replies that the worlds are like the apples on their tree, some “splendid and sound—a few blighted.” When he asks which they live on, a splendid one or a blighted one, Tess replies, “A blighted one.”

This comment sums up the world view of modernism.

Modernism in literature, approximately 1910 to 1945, is characterized by a feeling of loss of any centering, stabilizing factor in life, a break with tradition, and a reaction against established society, religion, and politics. Modernism sees humankind as lacking free will; instead individuals are victims of the circumstances in which they find themselves, victims of the environment much like animals. In addition, God, if there is a God, is detached from human affairs; a divine power may have set the world in motion, but the world now runs according to natural law without divine intervention. Writers such as T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, and Virginia Woolf experimented with new forms of literature and new subject matter which explored and depicted modernism as it affected individual lives.

Modern novels attempt to present the reality of the mind, not of the external world. In fact, the narrative tends to reflect what modern writers felt was a lack of order and reason in the world. Novelists such as Virginia Woolf and James Joyce use a stream of consciousnessA narrative style which attempts to reproduce the random thought patterns of the human mind, affected by external stimuli and mental association. technique, a narrative style which attempts to reproduce the random thought patterns of the human mind, affected by external stimuli and mental association. This narrative technique tends to ignore conventions of punctuation and mechanics, much as they do not figure in one’s thoughts.

In poetry, imagismAn early 20th century movement in poetry that favored clear visual pictures painted with concrete, concise language., an early 20th century movement in poetry, favors clear visual pictures painted with concrete, concise language. Imagism promotes the use of hard images, sparse but specific language, and irregular meters. The imagists spurred a new interest in the 17th-century Metaphysical poets and their metaphysical conceits.

Early 20th-century drama reflects all the characteristics that permeate the time period: the alienating effects of technology, the loss of faith in traditional values, the feeling of purposelessness of life. Dramatists often attempted to shock and challenge audiences. Experiments in staging and stagecraft paralleled experiments in other genre. Leading 20th-century dramatists include Nobel Prize winner Harold Pinter. Pinter’s plays such as The Dumb Waiter (1957) belong to the theatre of the absurdA type of drama intended to show the lack of meaning in modern life by depicting characters in senseless, hopeless situations speaking confusing, sometimes nonsensical dialogue. (a type of drama intended to show the lack of meaning in modern life by depicting characters in senseless, hopeless situations speaking confusing, sometimes nonsensical dialogue), with its portrayal of an individual’s lack of control over life, the impossibilities of communication among human beings, and social inequities.

The U.K.’s The Theatres Trust provides a history of theatre building in the first quarter of the 20th century, the effects of World War I and the precursors of cinema, and the state of the theatre during and immediately after World War II. The Victoria and Albert Museum provides a brief history of early 20th-century drama, as does Theatre Database. Theatre Database also includes an article on surrealism, theatre of the absurd, and major 20th-century playwrights and plays.

The New Elizabethan Age and Postcolonial Literature

Upon the death of King George VI in 1952, Elizabeth acceded to the throne as Queen Elizabeth II. Her realm, however, looked quite different from that of her great-great-grandmother Queen Victoria, who died only 51 years earlier.

By the end of the world wars, the British Empire no longer existed, replaced by the British Commonwealth. Countries that had been British colonies had over time become independent nations; many of those remaining colonies into the 20th century were granted their independence but remained dominions, rather than colonies, of Britain.

Postcolonial literatureLiterature written in the English language by residents of former British colonies. generally refers to literature written in the English language by residents of former British colonies. The subject matter of postcolonial literature typically addresses the oppression and exploitation of colonialism, the attempt to establish a national identity after independence, and the effects of colonialism and its aftermath on the individual. Emory University provides a Postcolonial Studies website that includes an introduction to postcolonialism, specific authors, themes, and issues typical of postcolonial discourse.

Among the questions raised about postcolonial literature is its place in studies of British literature. Does postcolonial literature belong in the category of “British” literature because the country of origin formerly belonged to the British Empire, or does the literature belong to the nationality which produced it? When the term English literature is used to designate literature written in the English language (rather than literature written in England or by English citizens), certainly postcolonial literature belongs in English literature studies, as would American literature, Australian literature, and the literatures of any other English-speaking countries. Some scholars therefore prefer the terminology “World Literature in English” to the word postcolonial that may, for some, perpetuate the paradigm of imperialists and their occupied victims. This term emphasizes the global view many scholars consider an important characteristic as well as a prime achievement of this literature. However, such an approach calls into question the inclusion in British literature studies of some writers traditionally considered British, such as Irish writers James Joyce and William Butler Yeats, both born in Ireland while it was a part of The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1801–1921) but both advocates of Irish independence.

Postmodernism

In his glossary of literary terms, Dr. L. Kip Wheeler of Carson-Newman College, characterizes postmodernism: “While modernism mourned the passing of unified cultural tradition, and wept for its demise in the ruined heap of civilization, so to speak, postmodernism tends to dance in the ruins and play with the fragments.”

A search for a definition of postmodernism leads many to the conclusion that the term is indefinable. Some proffered descriptions of postmodernism negate the possibility of definition by explaining that postmodernism pushes to an extreme the modernist idea that life and thought have no central core of reality or meaning. Epistemology becomes reliant on the individual mind, and a plurality of epistemologies is considered not only possible but desirable. Only cultural constructs provide what is accepted as reality and truth.

Postmodernism may be placed in time: the years following World War II to the last decade of the 20th century. During the 1990s and the early 21st century scholars began to speak of being in a post postmodern era.

Postmodern literature exhibits some of the same traits as modern literature but pushes these traits to extremes beyond those of the modern era. For example, modernism’s attempts to reproduce the way the human mind works with a stream of consciousness technique lead to postmodern mixing of points of view and deliberate playing with chronology, often for the purpose of questioning realism’s ontology. Harold Pinter’s use of reverse chronology in his 1978 play Betrayal, for example, exemplifies a postmodern manipulation of time. In a postmodern world, realism and the possibility of absolute truth, moral truth or empirical truth, do not exist. One hundred years after the Victorians grappled with a faith-doubt conflict, the postmodern world embraced nihilismA philosophy which denies the existence of an objective, knowable reality, intrinsic meaning in life, and absolute moral values. (a philosophy which denies the existence of an objective reality, intrinsic meaning in life, and absolute moral values) in reality and morality.

As a means of exploring the construct of reality, postmodernism employs metafictionFiction about the process of creating fiction., fiction about the process of creating fiction. A literary work in which both the author and the reader are conscious of the artifact as a creation of the author’s mind mirrors the process of the mind constructing reality.

Descriptions of modernism and postmodernism including a comparative chart are available from Dr. Martin Irvine at Georgetown University.

Post Postmodernism

Although many scholars would agree that the arts, including literature, have moved beyond postmodernism, there is no agreement on a description or characteristics of the current era, most agreeing that history will make those determinations.

The Development of the English Language in the Twentieth Century

Through the 20th century, English became a global language. Although early in the century British and American imperialism played a role, the changing nature of communication and technology now demands a common language in politics, economics, manufacturing, trade, travel, science, technology, indeed in all human endeavors.

Key Takeaways

- Joseph Conrad’s criticism of imperialism and Hardy’s depiction of the 20th century as a time of uncertainty and lack of belief served as precursors of dominant philosophies of the 20th century.

- Modernism in literature, approximately 1910 to 1945, is characterized by a feeling of loss of any centering, stabilizing factor in life, a break with tradition, and a reaction against established society, religion, and politics.

- Post-colonial literature evolved as former colonies gained their independence and often addresses the resultant issues.

- Postmodernism describes literature produced after World War II which often, sometimes in an ironic fashion, pushes the concerns of modernism to extremes.

Exercise

- Using the websites listed in Resources: Development of the English Language as a starting point, defend or contradict the claim that English has become or will become a global language. Look for specific fields or activities in which English is used globally.

Resources

General Information

- “Britain 1906–1918: Contrast, Contradiction & Change.” The National Archives.

- The Modern Word. Allen B. Ruch, editorial director.

- A Survey of 19th-Century & 20th-Century Literature. Jan Pridmore. Literary History.com.

Edwardian England

- “Edward VII: The First Constitutional Monarch.” Lucy Moore. British History. BBC.

- “The Edwardian Era.” Eras of Elegance.

World War I

- The First World War Poetry Digital Archive. University of Oxford and JISC [Joint Information Systems Committee].

- “Home Front: World War One.” British History. BBC.

- “Overview: Britain and World War One, 1901–1918.” British History. BBC.

- “—the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War.” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

Modernism

- “A Brief Guide to Modernism.” Academy of American Poets. Poets.org.

- British Drama 1890 to 1950: A Critical History. Richard Farr Dietrich, University of South Florida. Twayne Publishers.

- “Imagism.” Prof. Al Filreis, University of Pennsylvania.

- “Modern Literature.” Prof. Tom Drake, University of Idaho.

- The Modern Period (1901 or 1914–1939). Dr. Jo Koster, Winthron University.

- “Modernism and the Modern Novel.” Prof. Christopher Keep, University of Western Ontario, Tim McLaughlin, and Robin Parmar. The Electronic Labyrinth.

- “Stream of Consciousness.” The International Society for the Study of Narrative. Georgetown University.

- Twentieth Century British Drama. John Smart. Series ed. Adrian Barlow. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- “Understanding Modernism, A Summary.” Prof. Tom Drake, University of Idaho.

- “What is Modernism?” Brenna Dugan, The University of Toledo Libraries.

Postcolonialism

- Contemporary Postcolonial and Postimperial Literature in English. National University of Singapore.

- The Empire Writes Back: Post-Colonial Caribbean Literature. Dr. Kathleen L. Nichols, Pittsburg State University, Pittsburg, Kansas.

- “Literary Theory and Schools of Criticism: Post-Colonial Criticism (1990s–present).” Purdue Online Writing Lab. Purdue University.

- Post-Colonial Criticism. Academic Earth. Dr. Paul H. Fry, Yale University.

- Post-Colonial Criticism: (1990s–present). Purdue Online Writing Lab. Purdue University.

Postmoderism

- “Literary Theory and Schools of Criticism: Postmodern Criticism.” Purdue Online Writing Lab. Purdue University.

- “Postmodernism.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Gary Aylesworth.

- “Postmodernity vs. the Postmodern vs. Postmodernism.” Approaches to Po-Mo. Dr. Martin Irvine, Georgetown University.

Development of the English Language

- “English in the Twentieth Century.” John Ayto. “Aspects of English.” Oxford English Dictionary.

- The Future of English: A Guide to Forecasting the Popularity of the English Language in the 21st Century. David Graddol. The British Council, 2000.

- “The Making of Modern Britain.” BBC History.

- “A Brief History of English, with Chronology.” Suzanne Kemmer. Rice University. Words in English.

- “The Role of English in the 21st Century.” Melvia A. Hasman. U.S. Department of State. Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs. Office English Language Programs.

8.2 Thomas Hardy (1840–1928)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Characterize the beginning of the 20th century as depicted in Thomas Hardy’s poetry.

- Identify elements of modernism in the poetry of Thomas Hardy.

- Evaluate the effect of “Drummer Hodge” in early 20th-century discourse on imperialism.

- Assess the opinion of traditional religion expressed in “Hap,” “The Impercipient,” and “The Darkling Thrush” and compare/contrast that expression with other works from the Victorian Era and the early 20th century.

Biography

Texts

- “The Darkling Thrush.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “The Darkling Thrush.” Poems of the Past and Present. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Dead Drummer [Drummer Hodge].” Poems of the Past and Present. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “Drummer Hodge or The Dead Drummer.” The Victorian Web.

- “Hap.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “Hap.” Wessex Poems and Other Verses. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Impercipient.” Wessex Poems and Other Verses. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Impercipient.” Wessex Poems and Other Verses. 1898. Bartleby.com.

- “The Ruined Maid.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “The Ruined Maid.” Poems of the Past and Present. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

Hardy’s memorial stone in Poets Corner, Westminster Abbey.

“Hap”

Although Hardy repudiated the claim, he was labeled “The Great Pessimist.” Hardy, instead, described himself as a melioristA person who believes the world and individuals have the potential for improvement., a person who believes the world and individuals have the potential for improvement. Nonetheless, the pessimistic tone of modernism permeates his work.

If but some vengeful god would call to me

From up the sky, and laugh: “Thou suffering thing,

Know that thy sorrow is my ecstasy,

That thy love’s loss is my hate’s profiting!”

Then would I bear, and clench myself, and die,

Steeled by the sense of ire unmerited;

Half-eased, too, that a Powerfuller than I

Had willed and meted me the tears I shed.

But not so. How arrives it joy lies slain,

And why unblooms the best hope ever sown?

—Crass Casualty obstructs the sun and rain,

And dicing Time for gladness casts a moan….

These purblind Doomsters had as readily strown

Blisses about my pilgrimage as pain.

In modernism, the proper response to fate beyond individual control is stoicism—an endurance of the pain and heartache of life with dignity and without complaint. Such stoicism is evident in Hardy’s poem “Hap.”

In “Hap” the title gives an important clue about the poem’s content: the word hap means chance.

The first two stanzas of the poem are just one sentence. It is important to note that the entire first stanza is an “if” clause. The speaker is not saying, “There is a vengeful god”; he is saying “If there were a vengeful god.” If there were a vengeful god that laughed at him, saying that his suffering provided pleasure for the vengeful god, then he would react as he describes in stanza 2.

If there were a vengeful god, then he would bear the suffering stoically, halfway finding comfort in the fact that at least there was some reason for his pain, at least some god was directing what happened to him.

Note the first short sentence of stanza 3: “But not so.” The monosyllabic words, each accented, emphasize the speaker’s conclusion. The “if” clause he proposes in stanza 1 is not so; in other words, there is no god, not even a vengeful one. This conclusion leads the speaker to ask why, then, he suffers in life—why are his hopes unfulfilled and his happiness ruined? The last four lines provide the answer to his question: it is simply chance. He personifies time, picturing Time rolling dice to see what will happen to him. It may be something good, or it may be something bad. Either way it’s simply a roll of the dice, a matter of “chance.”

“The Impercipient”

As in “Hap,” the title “The Impercipient” provides an important clue about the poem’s content. The word impercipient is from the same Latin root word as the words perceive and perceptive. The prefix “im” means not. Therefore, this poem is about a person who does not perceive or understand.

The Impercipient (at a Cathedral Service)

That from this bright believing band

An outcast I should be,

That faiths by which my comrades stand

Seem fantasies to me,

And mirage-mists their Shining Land,

Is a drear destiny.

Why thus my soul should be consigned

To infelicity,

Why always I must feel as blind

To sights my brethren see,

Why joys they’ve found I cannot find,

Abides a mystery.

Since heart of mine knows not that ease

Which they know; since it be

That He who breathes All’s Well to these

Breathes no All’s Well to me,

My lack might move their sympathies

And Christian charity!

I am like a gazer who should mark

An inland company

Standing upfingered, with, “Hark! hark!

The glorious distant sea!”

And feel, “Alas, ‘tis but yon dark

And wind-swept pine to me!”

Yet I would bear my shortcomings

With meet tranquillity,

But for the charge that blessed things

I’d liefer have unbe [not be].

O, doth a bird deprived of wings

Go earth-bound wilfully!

…

Enough. As yet disquiet clings

About us. Rest shall we.

“The Darkling Thrush”

“The Darkling Thrush,” written at the beginning of a new century, is a statement of sharp contrast to the philosophy of the Romantic Period, one hundred years before this poem was written. Hardy dated the poem 31 December 1900, the eve of the new century.

Cottage where Hardy was born.

The Darkling Thrush

I leant upon a coppice gate

When Frost was spectre-gray,

And Winter’s dregs made desolate

The weakening eye of day.

The tangled bine-stems scored the sky

Like strings of broken lyres,

And all mankind that haunted nigh

Had sought their household fires.

The land’s sharp features seemed to be

The Century’s corpse outleant,

His crypt the cloudy canopy,

The wind his death-lament.

The ancient pulse of germ and birth

Was shrunken hard and dry,

And every spirit upon earth

Seemed fervourless as I.

At once a voice arose among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited;

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume,

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the growing gloom.

So little cause for carolings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

The speaker recounts leaning on a gate leading into a coppice, a small wooded area, on a gray, frosty day. The world appears drab and dark (the “weakening eye of day” referring to the sun’s inability to penetrate the gloom). No people are out enjoying nature, as is often portrayed in Romantic poetry; they have all sought the warmth of human companionship around their household fires. The entire first stanza sets the stage with images of death.

In the midst of this description, Hardy draws attention to the bare, tangled branches, comparing them with the strings of a broken lyre. His image is chosen purposefully. Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s image of the eolian harp (lyre) is one of the central images of Romantic poetry. “The Eolian Harp” was first printed in 1796, just over one hundred years earlier. The eolian harp symbolizes Romantic mysticism, a spiritual presence in the world (Coleridge’s “one Life, within us and abroad”) moving through nature, including human beings. Hardy says the eolian harp is now broken; that image no longer works. His universe is not spirit-filled, but lifeless and dried up. The land itself looks like a corpse.

Suddenly, in the midst of the frozen, dead world, the speaker hears the joyful song of a thrush, not a beautiful, vibrant bird like Shelley’s skylark, but a “frail, gaunt, and small” bird, worn out by storms.

In the final stanza, the speaker notes that the scene around the bird is bleak, certainly nothing to sing about, which leads him to state:

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

For over one hundred years, critics have disagreed about how to interpret these last four lines. There are two possibilities and scholars who support each side.

Possibility 1: There is some “Hope” in the world. Things aren’t as bleak as they seem. The bird is aware of a reason for hope, even if the speaker is not.

Possibility 2: The last two lines should be interpreted, “The bird may think there’s a reason for hope, but I, the speaker, surely don’t know what it is.”

The title of the poem could be seen as supporting either interpretation. The word darkling means “in the dark.” That phrase, however, could be interpreted literally (the bird is singing on a dark, cloudy day—”in the dark”) or figuratively (the bird is clueless—”in the dark”—the bird doesn’t know what’s going on, how bleak the world really is).

“The Ruined Maid”

Hardy’s audience would have recognized the expression ruined maid although we no longer use the phrase. They would have known immediately that the poem is about an unmarried woman who has lost her virginity. “The Ruined Maid” is, in fact, about two women: one who is “ruined” in a moral sense and another who, though chaste, is living a life of hardship and poverty.

The dialogue of the two women soon reveals that Melia, the ruined maid, is living in town, wearing beautiful clothes and jewelry, living a life of ease. The country woman, though virtuous, wears tattered clothes, digs potatoes to eke out a living, and envies ‘Melia. In the last two lines of the poem, ‘Melia tells her friend that she can’t expect a life of ease; she isn’t “ruined.”

The poem is humorous in effect, but it makes a serious point. Hardy leads the audience to ask themselves about society’s values and the way society works. Isn’t something wrong when virtue leads to poverty and “being ruined” leads to prosperity?

The Ruined Maid

“O ‘Melia, my dear, this does everything crown!

Who could have supposed I should meet you in Town?

And whence such fair garments, such prosperity?”—

“O didn’t you know I’d been ruined?” said she.

“You left us in tatters, without shoes or socks,

Tired of digging potatoes, and spudding up docks;

And now you’ve gay bracelets and bright feathers three!”—

“Yes: that’s how we dress when we’re ruined,” said she.

—”At home in the barton you said `thee’ and `thou,’

And `thik oon,’ and `theäs oon,’ and `t’other’; but now

Your talking quite fits ‘ee for high company!”—

“Some polish is gained with one’s ruin,” said she.

—”Your hands were like paws then, your face blue and bleak

But now I’m bewitched by your delicate cheek,

And your little gloves fit as on any lady!”—

“We never do work when we’re ruined,” said she.

—”You used to call home-life a hag-ridden dream,

And you’d sigh, and you’d sock; but at present you seem

To know not of megrims or melancholy!”—

“True. One’s pretty lively when ruined,” said she.

—”I wish I had feathers, a fine sweeping gown,

And a delicate face, and could strut about Town!”—

“My dear—a raw country girl, such as you be,

Cannot quite expect that. You ain’t ruined,” said she.

“Drummer Hodge”

Before and after the turn of the century the British were involved the Boer Wars. In a portion of what is now the Republic of South Africa, Dutch farmers settled and farmed peacefully throughout much of the 19th century. The native African people had already been defeated and driven off their land by European settlers. When gold and diamonds were discovered, the British were no longer content to let the Dutch settlers rule the area, and the struggle for control of the region and its riches grew into a horrific armed conflict.

The British set up concentration camps (the first time in history this term had been used) to imprison women and children of the Boer farmers who continued to fight. Loss of life among the British, the Boer fighters, and the innocent families was staggering. Hardy personalizes the loss of life by introducing his readers to one individual. In “Drummer Hodge,” originally titled “The Dead Drummer,” Hardy laments a young boy sent for the first time away from home to fight and die in a land he knew nothing about for a cause that mattered little if at all to him.

Drummer Hodge

I

They throw in Drummer Hodge, to rest

Uncoffined,—just as found:

His landmark is a kopje-crest

That breaks the veldt around;

And foreign constellations west

Each night above his mound.

II

Young Hodge the Drummer never knew—

Fresh from his Wessex home—

The meaning of the broad Karoo,

The Bush, the dusty loam,

And why uprose to nightly view

Strange stars amid the gloam.

III

Yet portion of that unknown plain

Will Hodge for ever be;

His homely Northern breast and brain

Grow to some Southern tree,

And strange-eyed constellations reign

His stars eternally.

Key Takeaways

- Bridging the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, Thomas Hardy’s poetry addresses questions that plagued Victorian society, such as imperialism, religion, traditional values, with a perspective that moves toward modernism’s view of the world as having no centering, stabilizing core.

- “Drummer Hodge” presents imperialism from an individual point of view, that of a boy sacrificed for reasons beyond his understanding.

- “Hap,” “The Impercipient,” and “The Darkling Thrush” depict a modern view of the world as lacking a transcendent spiritual power and therefore at the mercy of fate.

- “The Ruined Maid” describes two young women who illustrate the failure of traditional societal values.

Exercises

“The Impercipient”

- Where is the speaker of “The Impercipient”?

- Who is the “bright believing band” the speaker refers to in line 1?

- Identify what the speaker refers to in the phrases “fantasies,” “mirage-mists,” and “Shining Land” in stanza 1.

- In stanza 2, we learn what it is that the speaker does not perceive. What is it he does not understand?

- The capitalized “He” in stanza 3 presumably refers to God. Does the speaker blame God for his lack of perception?

- Explain the metaphor employed in stanza 4.

- In stanza 5 the speaker claims that he could bear his lack of perception calmly, stoically as it were, except for one “charge,” one accusation. What is that accusation?

- The speaker answers this charge in the abbreviated stanza 6 with another metaphor. To what does he compare himself? How does this metaphor relate to the accusation?

- Does the speaker reach a resolution to his lack of perception? How does the poem conclude?

“The Darkling Thrush”

- Compare the descriptive details of nature in “The Darkling Thrush” with the descriptions found in Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, or Keats.

- Account for Hardy’s choice of the words “spectre” and “haunted” in stanza 1.

- What is the purpose of describing the thrush as “frail, gaunt, and small” and “blast-beruffled”?

- Look up the various meaning of the word darkling in the Oxford English Dictionary. Particularly note any definitions and quotations from around the same time period Hardy was writing. Do the definitions affect your interpretation of the last stanza of the poem?

- How do you interpret the last stanza?

“Drummer Hodge”

- What is the effect of describing Drummer Hodge as being tossed into a grave with no coffin?

- What is the purpose of naming features such as the kopje and the veldt that are unfamiliar to Hodge?

- Why does Hardy refer to the stars in the final stanza?

Resources

General Information

- “Thomas Hardy 1840–1928.” The Victorian Web. George P. Landow, Brown University.

- “Thomas Hardy’s Poetry—Study Guide.” Andrew Moore. www.universalteacher.org.uk.

- “Turning the Century With Thomas Hardy.” Dr. James K. Chandler, University of Chicago. Fathom Archive. The University of Chicago Archive Digital Collections.

Biography

- “A Chronology of the Life and Works of Thomas Hardy.” The Victorian Web. Philip V. Allingham, Lakehead University.

- “Thomas Hardy.” Academy of American Poets. Poets.org.

- “Thomas Hardy.” Dr. John P. Farrell, University of Texas. Studies of Victorian Literature.

- “Thomas Hardy: A Biographical Sketch.” Dr. Andrzej Diniejko, Warsaw University.

Texts

- “The Darkling Thrush.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “The Darkling Thrush.” Poems of the Past and Present. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Dead Drummer [Drummer Hodge].” Poems of the Past and Present. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “Drummer Hodge or The Dead Drummer.” The Victorian Web.

- “Hap.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “Hap.” Wessex Poems and Other Verses. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Impercipient.” Wessex Poems and Other Verses. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Impercipient.” Wessex Poems and Other Verses. 1898. Bartleby.com.

- “The Ruined Maid.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “The Ruined Maid.” Poems of the Past and Present. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

Audio

- “The Darkling Thrush.” LibriVox.

- “The Darkling Thrush: Hardy’s Timely Meditation on the Turning of an Era.” Slate 30 Dec. 2008. Poet Robert Pinsky’s comments and reading of the poem.

- “Drummer Hodge (The Dead Drummer).” LibriVox.

- “Hap.” Wessex Poems and Other Verses. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Impercipient.” Wessex Poems and Other Verses. David Price, ed. Macmillan and Co., 1919. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Ruined Maid.” LibriVox.

Video

- “Peggy Ashcroft Reading Thomas Hardy.” (“The Ruined Maid”). AthenaLearning. YouTube.

- “Thomas Hardy.” Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.

Images

- Thomas Hardy and His Wessex.

- “Thomas Hardy’s Dorset.” Literary Landscapes. British Library.

Concordance

- A Hyper-Concordance to the Works of Thomas Hardy. The Victorian Literary Studies Archive. Mitsu Matsuoka, Nagoya University.

8.3 Joseph Conrad (1857–1924)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Determine various layers of meaning of the title Heart of Darkness.

- Identify and assess elements of modernism in Heart of Darkness.

- Judge the effect Heart of Darkness may have had on an audience predisposed to favor British imperialism.

Biography

Joseph Conrad was born in Poland. When his father was arrested on political charges and sent into exile in Russia, his wife and their young son Joseph accompanied him. The harsh weather and living conditions resulted in the early deaths of his parents and in health problems that plagued Conrad throughout his life. Conrad lived for a time with an uncle but in his teens began a career on the sea that took him on many adventures that later appeared in his writing. His voyage up the Congo River formed the basis of Heart of Darkness. One voyage took him to England where he joined a crew that included Englishmen from whom he began to learn the language. He eventually became an English citizen, married an English woman, and when his health forced him to retire from his maritime career, lived the rest of his life in England. Conrad had been writing throughout his life, but his retirement allowed him to devote the time and attention to his writing that he had desired.

Text

- Heart of Darkness. Electronic Text Center. University of Virginia Library.

- Heart of Darkness. A Penn State Electronic Classics Series Publication. Pennsylvania State University.

- Heart of Darkness. Project Gutenberg.

Heart of Darkness

A story about Conrad’s childhood claims that he once randomly placed a finger on a far-away place on a map and stated that when he was grown up he would go there. The place was Africa. In Heart of Darkness, Conrad attributes this event to his narrator, Charles Marlow. In his novellaA work with the characteristics of a novel but shorter and less complex in plot., a work with the characteristics of a novel but shorter and less complex in plot, Heart of Darkness, Conrad draws on his own experience as a riverboat captain sailing up the Congo River.

Heart of Darkness was originally published serially in Blackwood’s Magazine, 1899. Uppsala University’s Conrad First website provides digital copies of the magazine.

Like Hardy’s work, Conrad’s writing bridges the end of the Victorian Era and the Modern Age of the early 20th century. His work, however, reveals characteristics that distinguish it as a modern work, distinctly different from the mores of Victorian literature.

Plot in Heart of Darkness is more mental than chronological and linear. Although we follow a chronology of events as Marlow experiences his journey to the Congo, that chronology is of less importance than Marlow’s mental journey of realization and awakening to the nature of the world. The reader reaches awareness about events and characters as the narrator does. The story takes the reader along with Marlow’s journey of discernment about life and human nature.

Characters often are not full drawn, realistic characters like those we might encounter in Dickens’s novels. Mental life, the life of the mind, Marlow’s mind, and then Kurtz’s mind, are the focus. Although Heart of Darkness pre-dates the important works of Freud and Jung, Conrad exhibits the interest in human psychology that would lead later modernist writers to study and reflect psychological studies in their works. Even the story’s religious and biblical imagery reinforces its rejection of traditional religious values and asserts the modernist tenet that there is no moral center. The basic depravity of humankind is no better than, often worse than, the instinctive behavior of animals. While humans may, as Darwin’s work suggested, work on instinct like animals, animals do not engage in the wanton, futile destruction depicted in Heart of Darkness.

The structure of Heart of Darkness uses a double narrator.

- At the beginning of the work, an unnamed narrator sets the scene in the story’s present time: on the ship Nellie on the River Thames in London in Marlow’s old age. This narrator is presumably, like Charles Marlow, a sailor on the Nellie; in the second paragraph he comments that the river Thames “stretched before us” and later notes that the men present have “the bond of the sea.”

- The main story is Marlow’s re-telling of his experience as a riverboat captain sailing up the Congo River. We don’t experience the events as they happen; we experience them through the filter of Marlow’s memory. As you read, watch for instances of the outer framework, the first unnamed narrator, breaking into Marlow’s story.

The themes of Heart of Darkness become apparent as we consider the title. The story is foremost a journey.

- In one sense, it is literally a story of a journey into the heart of darkness that is, in the view of many turn-of-the-20th-century Europeans, the African continent. Because they knew little about Africa, Europeans referred to Africa as “the dark continent.”

- At another level, Marlow’s initial desire for an adventure turns into a quest for Kurtz, the mysterious star of the company. He collects more ivory and therefore more money than any other company agent. Marlow hears about him at every turn. At this level, the story also functions as a criticism of European imperialism. Kurtz embodies the concept of robbing another country of its natural resources and laying waste, not just to its land, but its population. The basis of his fame is that Kurtz excels in making money from a land that does not belong to him.

- At its most important level, Marlow’s journey becomes a pilgrimage to the heart of humankind’s depravity. As he moves deeper into the literal darkness of the jungle and closer to Kurtz’s presence, he experiences an epiphanyA sudden moment of insight and revelation., a sudden moment of insight and revelation. Marlow’s epiphany is a realization that humankind possesses a core of evil, a heart of darkness. Although the story is not told primarily in religious terms, the presence of original sin, a person’s innate capacity for evil—a heart of darkness—is at the terminus of Marlow’s physical, mental, and spiritual journey.

Key Takeaways

- Heart of Darkness may be interpreted literally as a journey into an unknown territory, metaphorically as Marlowe’s realization of evil, or symbolically as humankind’s natural propensity for evil.

- Heart of Darkness evinces modernism in its narrative technique and in its central theme that at the culmination of the search for meaning in human life is only darkness.

- On one level of meaning, Heart of Darkness is a criticism of imperialism.

Exercises

- In Heart of Darkness, Kurtz is involved with two women, one African and one European. Compare the two women. What similarities do they have? What differences? What is their relationship with Kurtz? Why are they important to the story?

- Describe the Africans in Heart of Darkness. What role do they play in the story? What qualities do they represent? What is their relationship with the Europeans?

- Describe the Europeans in Heart of Darkness. What role do they play in the story? What qualities do they represent? What is their relationship with the Africans?

- Describe Marlow. How does he change from the beginning to the end of the story?

- At the beginning of his narration, Marlow states, “And this [England] also…has been one of the dark places of the earth.” He refers to the time of the Roman Empire, when that great civilization sent men to conquer Britain, a country foreign in language, culture, climate, almost every conceivable way. How does this comment prepare readers for the story to follow? In what ways has England been one of the “dark” places on earth? How could this statement be interpreted as a statement on imperialism, on empire-building?

- At the beginning and the end of his story, Marlow is in Europe. What descriptive details suggest that Europe is a place of darkness as much as Africa?

- Marlow recognizes even before he lands in Africa that the European presence there is futile and destructive to the environment as well as the people. List descriptions and events that picture this destruction.

- One of the first people Marlowe meets in Africa is the Company’s chief accountant. Marlowe gives a detailed description of his appearance. What does his appearance say about the European presence in Africa?

- Near the end of the story, when Marlow follows Kurtz back into the jungle, he tells readers, “But his [Kurtz’s] soul was mad. Being alone in the wilderness, it had looked within itself, and, by heavens! I tell you, it had gone mad.” It was not the outside surroundings that made Kurtz mad; it was looking into his own soul. How does this statement elucidate the theme of Heart of Darkness? Marlow next tells us that, he supposes for his sins, he also has to look into Kurtz’s soul. What change does this revelation effect in Kurtz?

- As Kurtz is dying, Marlow hears him say, “I am lying here in the dark waiting for death.” Marlow’s response is that this statement is nonsense because there is a candle within a foot of his eyes. How would you account for Kurtz’s statement? Does Marlowe deliberately misinterpret Kurtz’s comment? Why or why not?

- The climactic moment of the story, the moment preceding Kurtz’s death, is expressed with religious and biblical images. Explain the reference to the “veil being rent.” What does Marlow find when the veil is rent and he comes face to face with the center, the heart, of humankind?

- Explain Kurtz’s last words, “The horror! The horror!”

- Why does Marlow lie to “the Intended” about Kurtz’s last words?

Resources

General Information

- Conrad First. The Joseph Conrad Periodical Archive. The Joseph Conrad Society UK and the Department of English, Uppsala University.

- “Heart of Darkness.” Dr. Pericles Lewis, Yale University. The Modernism Lab at Yale University. information on elements of modernism in Heart of Darkness.

- Vox Et… . Dr. David Mulry, ed. Schreiner University. podcasts of comments from Conrad scholars.

- “White Lies and Whited Sepulchres in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.” The Victorian Web. Philip V. Allingham, Lakehead University.

Biography

- Joseph Conrad: A Biographical Note. Zdzisław Najder. Joseph Conrad Study Centre in Opole, Poland.

- Joseph Conrad (Teodor Josef Konrad Nalecz Korzeniowski) 1857–1924. The Victorian Web. Philip V. Allingham, Lakehead University.

Text

- Heart of Darkness. Electronic Text Center. University of Virginia Library.

- Heart of Darkness. A Penn State Electronic Classics Series Publication. Pennsylvania State University.

- Heart of Darkness. Project Gutenberg.

Concordance

- A Hyper-Concordance to the Works of Joseph Conrad. The Victorian Literary Studies Archive. Mitsu Matsuoka, Nagoya University.

Audio

- Heart of Darkness. LibriVox.

- Heart of Darkness Audiobook Podcast. Learn Out Loud.com.

- Vox Et… . Dr. David Mulry, ed. Schreiner University. podcasts of comments from Conrad scholars.

Images

- Heart of D—the Horror! Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. digital image of page of Conrad’s original manuscript.

8.4 The War Poets

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Understand the effects of World War I on Britain and on the development of Modern literature.

- Recognize the cognitive dissonance caused by accounts of the achievements and victories of the British military and the firsthand accounts of returning individuals and of writers such as the war poets.

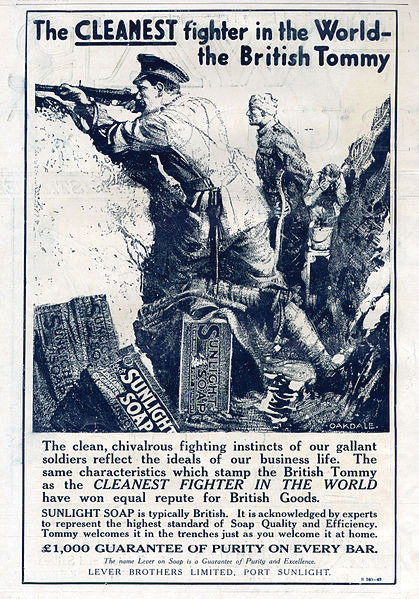

No words could describe the general public’s perception of World War I better than the photo essay at the Modern American Poetry website (Editors: Cary Nelson and Bartholomew Brinkman. Department of English. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign). In the photo essay note the first pictures of men going off to war, women cheering them on, both sides confident in their abilities and confident that the war would be over within a few months followed by increasingly somber pictures of the reality. The ad pictured here capitalized on the widespread belief that British troops, because they were honorable, chivalrous, gallant, would soon march home in victory. The work of soldier poets such as Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, and Rupert Brooke informed the British public of the realities of war as much as, perhaps more than, the censored journalistic reports that reached British newspapers and magazines. The brutalities of outdated military tactics used against modern weapons resulted in incomparable British losses. The war poets painted vivid pictures of the realities of war.

The BBC provides extensive information about World War I, including virtual tours of the trenches and excerpts from oral histories, diaries, and letters.

Wilfred Owen (1893–1918)

Wilfred Owen was born in Shropshire, a rural area of England. He was interested in poetry, particularly Keats and other Romantic poets, and wrote poetry in his teens. When he failed to be admitted to college, he moved to France to work as an English language tutor. After World War I began, he moved back to England to enlist. In 1917, he was diagnosed with what was then called shell shock and sent to Craiglockhart Hospital in Scotland for treatment. There he met Siegfried Sassoon. Both poets wrote some of their most well-known poetry while there. Owen returned to the front in the fall of 1918, won the Military Cross, and just days before the war ended was killed in battle. His family received the news of his death in the midst of celebrations on November 11, Armistice Day, 1918.

“Dulce et Decorum Est”

The Latin phrase from a work by Homer may be translated “It is sweet and right to die for one’s country.” Juxtaposed against the illusion of war as a glorious adventure, Owen paints the horrors of war’s reality.

Dulce et Decorum Est

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime…

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

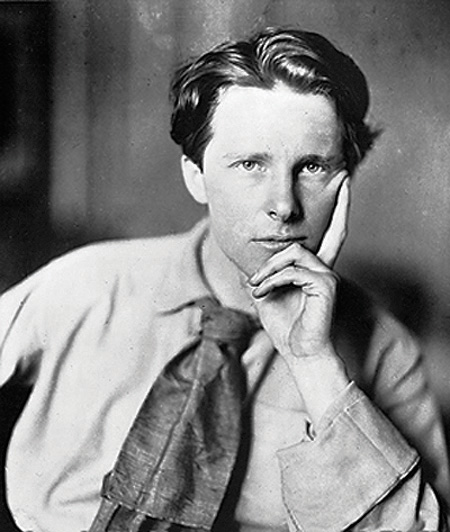

Rupert Brooke (1887–1915)

Rupert Brooke also was fond of the works of the Romantic poets. He attended Cambridge University where he met and befriended members of the Bloomsbury Group whose literature was an important piece of British modernism. Brooke was commissioned into the Royal Navy, but in 1915 he died of sepsis onboard a hospital ship. He is buried on the Greek island of Skyros.

Rupert Brooke’s grave.

“The Soldier”

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England’s, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967)

Although Sassoon grew up in a family divided by religious differences, his father was Jewish, his mother Roman Catholic, his background provided him enough wealth to live comfortably. He attended Cambridge University for a while, without taking a degree, preferring to live the life of a country gentlemen playing cricket and writing. Sassoon joined the British Army at the beginning of World War I; he was sent home from the front twice, once when he contracted a fever and once for shell shock, this being the occasion when he met Wilfred Owen. Sassoon survived World War I and continued writing until his death.

By George Charles Beresford, 1915

“Glory of Women”

Glory of Women

You love us when we’re heroes, home on leave,

Or wounded in a mentionable place.

You worship decorations; you believe

That chivalry redeems the war’s disgrace.

You make us shells. You listen with delight,

By tales of dirt and danger fondly thrilled.

You crown our distant ardours while we fight,

And mourn our laurelled memories when we’re killed.

You can’t believe that British troops “retire”

When hell’s last horror breaks them, and they run,

Trampling the terrible corpses—blind with blood.

_O German mother dreaming by the fire,

While you are knitting socks to send your son

His face is trodden deeper in the mud._

In the last three lines, the speaker turns from addressing the people back home in England to speak to the imagined mother of a German soldier. His comment has the effect of humanizing the political enemy.

Key Takeaways

- The staggering casualties and the horrors of modern warfare contributed to the modernist sense that the world lacks a stable, centralizing force and that life lacks ultimate purpose—that the world we live in is, in the words of Thomas Hardy’s character Tess, a “blighted one.”

- The work of the war poets helped enlighten the public about the nature of the war experience.

Exercises

- In “Dulce Et Decorum Est” the last stanza is directed to people back at home. What is the purpose of this stanza?

- Read this brief description of the mustard gas used in World War I. Does Owen’s description seem realistic? Which account seems more emotionally based? Which might have had a more profound effect on the people at home away from the war?

- Brooke’s poem “The Soldier” seems brighter in mood and tone than the other two poems, and yet it describes a soldier’s death. What makes the poem less horrific than “Dulce Et Decorum Est”?

- How would you describe the mood of the speaker in “The Soldier”?

- The speaker of “Glory of Women” expresses disillusionment with the supposed glory of war. How would you describe his attitude toward the women back at home?

- In “Glory of Women,” although the Germans are the enemy of the British, what common human trait does the poet reveal?

Resources

General Information

- Anthem for Doomed Youth: Writers and Literature of The Great War, 1914–1918. An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

- The First World War Poetry Digital Archive. University of Oxford and JISC [Joint Information Systems Committee]. text (including biographies, primary texts, background information), images (including portraits, digital images of manuscripts, photos of World War I, images from the Imperial War Museum); audio; video (including a Second Life Virtual Simulation from the Imperial War Museum and a YouTube video introduction, over 150 video clips, film clips), and an interactive timeline.

- “Home Front: World War One.” British History. BBC.

- “—the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War.” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “Wilfred Owen’s ‘Dulce et Decorum Est.’” Online Gallery. British Library. image of handwritten manuscript and information about Owen and World War I.

- “World War One.” World Wars. BBC History.

Biography

- Poems by Wilfred Owen with an Introduction by Siegfried Sassoon. A Penn State Electronic Classics Series Publication. Pennsylvania State University.

- “Rupert Brooke, 1887–1915.” “—the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War.” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “Rupert Brooke (1887–1915).” Historic Figures. BBC.

- “Rupert Chawner Brooke.” An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

- “Siegfried Sassoon.” An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

- “Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967).” Historic Figures. BBC.

- “Wilfred Owen (1893–1918).” Historic Figures. BBC.

- “Wilfred Owen (1893–1918).” “—the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War.” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “Wilfred Edward Salter Owen.” An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

Texts

- “1914 V. The Soldier“ by Rupert Brooke. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “Anthem for Doomed Youth.” by Wilfred Owen. An Exhibit Commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the Armistice, November 11, 1918. Robert S. Means. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University. text and a digital image of the original handwritten manuscript.

- “Dulce et Decorum Est.” by Wilfred Owen. Paul Halsall, Fordham University. Internet Modern History Sourcebook.

- “Dulce et Decorum Est.” by Wilfred Owen. “—the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War.” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “Glory of Women.” by Siegfred Sassoon. Counter-Attack and Other Poems. 1918. Bartleby.com.

- “Glory of Women.” The War Poems of Siegfried Sassoon. Project Gutenberg.

- “Sonnet V. The Soldier.” by Rupert Brooke. “—the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War.” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

Images

- “Wilfred Owen’s ‘Dulce et Decorum Est.’” Online Gallery. British Library.

- “World War I Photo Essay.” Modern American Poetry. Editors: Cary Nelson and Bartholomew Brinkman. Department of English. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Audio

- “Dulce et Decorum Est.” by Wilfred Owen. LibriVox.

- Extract from a letter by Wilfred Owen, July 1918. “—the rest is silence.” Lost Poets of the Great War.” Harry Rusche, Emory University.

- “Siegfried Sassoon 1886–1967). A Recording Owned by Mrs. Olga Ironside Wood. 1 January 1967. BBC.

- “The Soldier.” by Rupert Brooke. LibriVox.

- “Wilfred Owen Audio Gallery.” Dominic Hibberd. World Wars. BBC History.

8.5 Virginia Woolf (1882–1941)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Ascertain the state of women’s rights during Virginia Woolf’s lifetime.

- Recognize the influence of the Bloomsbury Group on modernism.

Biography

Video Clip 2

Virginia Woolf

(click to see video)Click to watch a video mini-lecture biography onWoolf.

Virginia Woolf.

by George Charles Beresford, 1902

The Bloomsbury Group

Originating in friendships established at Cambridge University, the Bloomsbury Group consisted of writers, artists, and intellectuals who influenced Modern British literature and art. The name Bloomsbury came from the neighborhood in London where several members of the group lived and worked. Their work and their lifestyles were bohemian and controversial, affecting modern views on feminism and sexuality as well as literary criticism, art, and publishing. The circle of friends now known as the Bloomsbury Group included Virginia Woolf and her husband Leonard Woolf, her sister Vanessa Bell and her husband Clive Bell, writer Lytton Strachey, writer E.M. Forster, and economist Maynard Keynes.

Text

- A Room of One’s Own. Project Gutenberg of Australia.

- A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf. eBooks@Adelaide. The University of Adelaide Library. University of Adelaide, South Australia.

A Room of One’s Own

In 1928, Virginia Woolf gave a series of lectures at Newnham and Girton Colleges, women’s colleges at Cambridge University. A year later, she published a revision of her lectures as A Room of One’s Own. Woolf’s premise that a woman must have “money and a room of her own” if she is to become a writer applies literally to becoming a career writer, but more broadly to the idea that women must have the independence and education to support themselves and the political freedom to assume such places in a society that gives preference to men. In speaking on this subject to women attending college, Woolf reminds them and future readers that women have had that right for only a brief time.

In one of the more well-known sections of her lectures, Woolf creates the fictional story of Shakespeare’s sister. What if, she surmises, Shakespeare had had a sister who was just as gifted and talented as Shakespeare himself? Would that sister, whom she calls Judith, have been able in the 16th century to become a writer like Shakespeare? Woolf tells a hypothetical story in which Judith attempts to follow her brother’s footsteps. Instead of being allowed to spend time reading and writing, Judith would have been beaten by her father and compelled to marry. She certainly would not have been allowed to attend school. Woolf describes Judith running away to London, where we know that Shakespeare himself had a successful career as an actor, the manager of a theatrical company, and of course a playwright. Judith, on the other hand, is unable, because of society’s restrictions on women, to do any of those things. Woolf’s hypothetical story is a reminder of what women have accomplished but also an appeal for women to continue to strive for equality.

Key Takeaways

- Virginia Woolf, like Mary Wollstonecraft over 130 years earlier, advocated educational opportunities for women.

- Virginia Woolf was a member of the literary coterie known as the Bloomsbury group.

Exercise

Like Mary Wollstonecraft over 100 years earlier, Virginia Woolf was concerned about the lack of educational opportunities for women. One method of exploring this concern is the hypothetical story she writes in the “Shakespeare’s Sister” section of A Room of One’s Own. What if, Woolf asks, Shakespeare, the greatest writer of the English language, had a sister who was just as talented, just as intelligent as he? Would we now be studying Shakespeare’s sister just as we study Shakespeare? Obviously, her answer is no. Societal factors in the 16th century would prevent Miss Shakespeare from becoming a writer. Her natural talent would be useless because sixteenth-century society would not allow her the opportunity to develop it.

From what you’ve learned about the Romantic Period, the Victorian Age, and the early 20th century, would a woman in these three time periods have a different experience from Woolf’s hypothetical Judith? Provide specific evidence to support your answer.

Resources

Biography

- “Virginia Woolf.” Chronology. Dr. Joe Pellegrino, Georgia Southern University.

- “Virginia Woolf.” Learning: Changing Language. British Library. brief biography, digital image of Woolf’s handwritten draft of Mrs Dalloway, and explanation of stream of consciousness.

- “Virginia Woolf.” Women’s History. Gale Cengage Learning.

- “Virginia Woolf (1882–1941): A Short Biography.” S. N. Clarke. Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain.

Bloomsbury Group

- “Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury.” Tate Learn Online.

- The Bloomsbury Group: Artists, Writers, and Thinkers.

- “Intimate Relations.” Cambridge Life. University of Cambridge.

Text

- A Room of One’s Own. Project Gutenberg of Australia.

- A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf. eBooks@Adelaide. The University of Adelaide Library. University of Adelaide, South Australia.

Guides and Discussion Topics for A Room of One’s Own

- Abyss Notes/Reading Guide for Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. Dr. Elisa Kay Sparks, Clemson University.

- Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own (1929). Prof. Catherine Lavender, The College of Staten Island of The City University of New York.

Audio

- A Selection from A Room of One’s Own. Listen To Genius! Redwood Audiobooks. Download for personal use only; not for distribution.

Video

- Virginia Woolf. Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.

- “Virginia Woolf’s Broadcasts at the BBC 1937.”

Images

- “Virginia Woolf.” Great Britons: Treasures from the National Portrait Gallery, London.

8.6 T.S. Eliot (1888–1965)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Identify elements of Modernism in T. S. Eliot’s poetry.

- Compare the imagery of Eliot’s poetry to the metaphysical conceits of John Donne or other metaphysical poets of the 17th century.

- Identify religious imagery in “East Coker” and determine its purpose.

- Determine what the choice of images reveals about the speaker’s character in “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.”

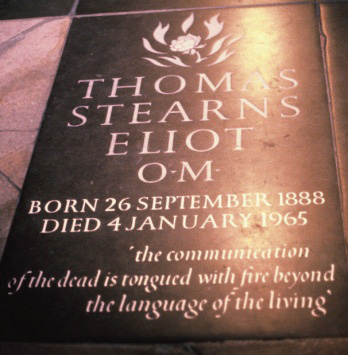

Anthologies of American literature as well as British literature contain T.S. Eliot’s work. Because Eliot is one of the great modernist poets, both countries are eager to claim him.

T.S. Eliot.

by Lady Ottoline Marrell 1934

Biography

T.S. Eliot was born in St. Louis, Missouri and attended Harvard University. After an additional year of education in Paris, he went to Oxford University and then back to Harvard. In 1914, he moved to and settled in England, marrying an English woman and working as a teacher and a banker. Here he met the American modernist poet Ezra Pound who encouraged Eliot’s writing. Eliot’s first publication, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” established him as an important modernist poet. Eliot began working at Faber and Faber publishing company, eventually becoming a director. He became a naturalized British citizen in 1927.

Chapter House at Canterbury Cathedral.

Eliot admired and helped foster a renewed interest in the 17th-century Metaphysical poets such as John Donne. Modernist poets appreciated their metaphysical conceits, striving to achieve hard images in their own writing, images that were clear and sharp due to precise, concise language.

Eliot also wrote verse dramas. Murder in the Cathedral recounts the martyrdom of Becket at Canterbury Cathedral in 1170. The work was first performed in the Chapter House at Canterbury Cathedral, only steps from where Becket’s murder took place.

In 1948, Eliot received the Nobel Prize for literature. He remarried later in life, and on his death in 1965, his second wife worked to compile and edit his papers and manuscript drafts of his work.

Eliot’s ashes are interred at East Coker Church, a small village in southwest England that was home to his ancestors.

He also is honored with a commemorative stone in Poets Corner, Westminster Abbey.

Texts

- Four Quartets. available through subscription database Chadwyck-Healey Literature Collection. Eliot, T. S. (Thomas Stearns), 1888–1965 [from Collected Poems 1909–1962 (1974)] , Faber and Faber.

- “Prufrock and Other Observations.” Project Gutenberg.

- “T.S. Eliot: The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1919).” Prof. Paul Brians, Washington State University.

- “The Waste Land.” Project Gutenberg.

“The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

Analyses of Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” often consist of as many questions as statements. The poem uses the modernist stream of consciousness technique, an effort to demonstrate the workings of the human mind. Knowing we are, in a sense, listening to an individual’s thoughts, leaves questions because we are not presented a consciously constructed narrative.

The title itself seems paradoxical with the pairing of the idea of a love song with a name as prosaic as J. Alfred Prufrock, a name Eliot suggested he may have remembered from the name of a furniture company in his native St. Louis.

The epigraph to “Prufrock” is from Dante’s Inferno. The epigraph’s speaker states that if his listener were returning to earth and therefore could repeat his story to others, he would not speak; however, since no one can return from Hell, he can speak his words. The epigraph leads readers of “Prufrock” to wonder if they are reading a dramatic monologue, in which the speaker addresses a specific listener, whether the readers are the auditors, or whether we are overhearing the workings of a human mind of which we ordinarily would not be aware. Are these words, like the epigraph speaker’s words, that are not meant to be heard by others?

This dilemma calls into question the reality of all the events of the poem. Is the speaker actually walking somewhere, or is he only rehearsing this possibility mentally? Is he imagining something that will happen, remembering something that has happened, or actually experiencing the event?

Brief Excerpts from “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherised upon a table;

The first three lines of the poem provide the type of unusual, unexpected comparison reminiscent of metaphysical conceits. In this love song, with the picture of a couple walking in the evening, the scene is compared to a patient under sedation upon an operating table, hardly a romantic image. The meter also emphasizes the incongruity of the simile: the first two lines are regular in meter, but the smooth rhythm stumbles with line 3.

There will be time, there will be time

To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet;

There will be time to murder and create.…

In lines 26–28, the speaker talks of preparing a face to meet other faces, of assuming a mask, a façade, to meet other people who are just as artificial, as counterfeit, as the speaker.

The references to the taking of toast and tea in a room where “women come and go / Talking of Michelangelo” suggest that the speaker is on his way to an afternoon tea attended by insincere people talking about topics intended to impress others. Here, too, however, we are left with the uncertainly of whether we are experiencing the events as the speaker does or whether the speaker is recalling or anticipating the occurrence.

The speaker imagines the crowd whispering about his inadequacies from his bald spot to his thinness until he feels like a bug specimen pinned under a scientist’s microscope. And all the time he wonders if he dares to “disturb the universe” by breaking out of the pattern of expected behavior.

I should have been a pair of ragged claws

Scuttling across the floors of silent seas.

In lines 73 and 74, the speaker states he should have been a pair of claws, a crab, on the floor of the sea, silent and far away from the world, from the critical eyes, living strictly by instinct with none of the angst resulting from his current situation.

Lines 75 through 110 present the speaker wondering how things might have been, or might be in the future, different if he had the courage to force the moment from the triviality of everyday life to the important questions. At the same time, he knows he did not, or will not, have the courage to speak his convictions or to pronounce the ideas which are important to him. The following lines provide the reason:

And I have seen the eternal Footman hold my coat, and snicker,

And in short, I was afraid.

He is too afraid to step out from behind the mask he prepared, the face he shows the world, the façade of conformity that makes him act like the rest of society safely behind their masks. The meaningless ritual in which he and those around him indulge characterizes the modernist view of life. Having realized that he will never address the important questions, the speaker rationalizes his behavior with the thought that in life’s drama he does not play a leading part, such as Hamlet, but only a bit part.

With the realization that he will never address the important issues of life, the speaker begins to imagine the rest of his life, sinking into an ever-more-powerless old age. The speaker claims in lines 124–126 he has heard mermaids singing.

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.

I do not think that they will sing to me.

I have seen them riding seaward on the waves.…

In British folklore, mermaids are often evil omens, sirens luring sailors to their deaths. In this context, the mermaids seem to represent something beautiful denied to the speaker. On the other hand, the following lines picture the speaker at the bottom of the sea with the mermaids, again, as when he pictures himself as a crab, isolated from human contact. The sound of human voices drowns him.

Whatever the specifics of Prufrock’s situation, the despair, the inability to shape his own circumstances, the lack of free will to make his desires reality all reflect the modernism of the early 20th century.

The Modern American Poetry website from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign provides a summary of seminal commentary on “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.”

Four Quartets: “East Coker”

Eliot wrote what would become the first of the Four Quartets, “Burnt Norton” and published it separately from the other three poems in a poetry collection in 1936. The other three poems, “East Coker,” “The Dry Salvages,” and East Giddings” were written during World War II, but the four were not published as a whole until 1943.

In music, a quartet consists of four different voices, the title thus suggesting multiple voices in each poem, each quartet. Although the more typical form for musical quartets, particularly string quartets, is four movements, notably Haydn’s quartets and Beethoven’s later quartets often have five movements. Each of Eliot’s poems consists of five parts.

The Four Quartets are often interpreted as representing the medieval idea of the fours elements: air, earth, water, and fire.