This is “Robert Burns (1759–1796)”, section 6.4 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

6.4 Robert Burns (1759–1796)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Understand Robert Burns’s position as the national poet of Scotland and his appeal to Romantic-era audiences as a natural poet, an example of primitivism.

- Identify characteristics of Romanticism in Burns’s poetry.

Duyckinick, Evert A. Portrait Gallery of Eminent Men and Women in Europe and America.

New York: Johnson, Wilson & Company, 1873.

Robert Burns is the national poet of Scotland. Although his poems are somewhat difficult to read because of the Scottish dialect, that dialect is one of the reasons Burns is a central pre-Romantic figure. Long before the popularity of 20th-century multi-culturalism, Burns preserved in his poetry the Scottish language, culture, and heritage. Burns embodies the concept of Romantic primitivism, and his poetry exemplifies the glorification of the common man, the individual educated by life and nature.

Biography

The son of a Scottish farmer, Robert Burns was born in this farmhouse in Alloway, Scotland in 1759. One end of the building housed the animals; the other, the family.

Burns attended the local school, had occasional tutors, and read voraciously. Because he lacked formal education, he was viewed as a natural poet, the exemplification of a Romantic ideal: a primitive plowman, close to nature, as capable of writing perceptive poetry as the university-educated aristocrat. After the publication of his Kilmarnock volume of poetry, Burns’s fame soared, and he was in demand in the highest social circles in Scotland.

Known as the National Poet of Scotland, Robbie Burns celebrated the folk legends, the history, and the language of Scotland. His poetry also glorified nature, the common individual, and rural Scottish life.

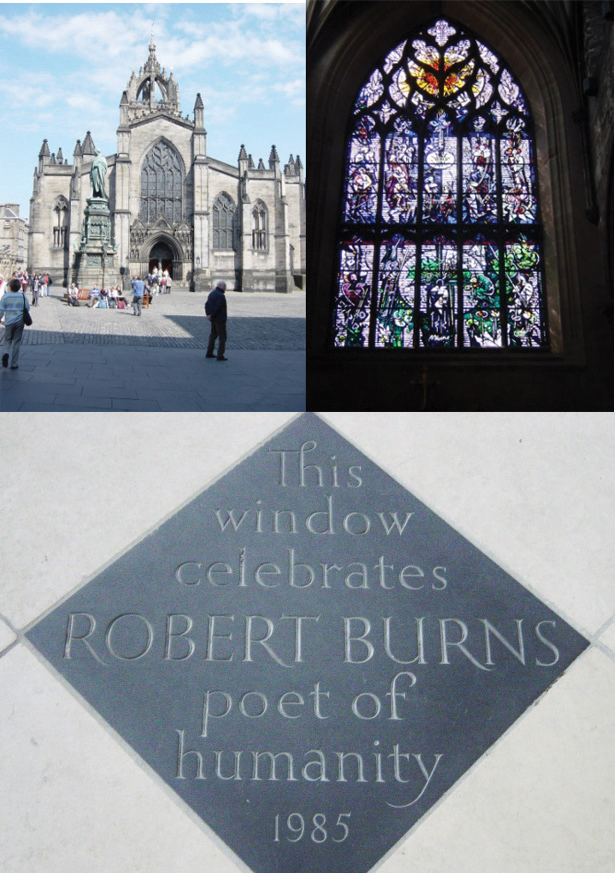

A stained glass window in St. Giles Church in Edinburgh, Scotland honors Burns, as do numerous monuments in Edinburgh, Alloway, and Dumfries where Burns lived.

Texts

- Books by Robert Burns. Project Gutenberg.

- Complete Works. Burns Country. includes glossary for Scottish words.

- Selected Poetry of Robert Burns. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

Audio

In addition to reading Burns’s poetry, listen to recordings in the Scottish dialect.

- “Kevin McFadden Reads ‘To a Mouse’ by Robert Burns.” Poets on Poets. Tilar Mazzeo, ed. Romantic Circles.

- “Robert Burns 250th Anniversary Collection.” LibriVox.

The Poetic Genius of my Country found me at the plough and threw her inspiring mantle over me. She bade me sing the loves, the joys, the rural scenes and rural pleasures of my native soil, in my native tongue; I tuned my wild, artless notes, as she inspired

…—quotation from a letter by Robert Burns.

“To a Mouse” and “To a Louse”

Both “To a Mouse” and “To a Louse” have a moral to the story.

In “To a Mouse,” a farmer plowing his field turns up a mouse’s nest, and the poem reports his speech to the mouse. Sympathetic, the farmer recognizes what was a popular idea among Romantic poets, the idea of man and nature in a “social union.” In Burns’s frequently quoted lines, the farmer states that even the most careful plans may “go astray” because of unforeseen circumstances:

The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men

Gang aft agley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

For promis’d joy!

In the final stanza, the farmer notes, despite this realization that neither man nor mouse can plan the future with any certainty, the mouse is still more blessed than the man. The present only affects the mouse; people, however, look back at the past and worry about the future.

Auld Kirk in Alloway, setting of Tam O’Shanter’s ghostly encounter.

In “To a Louse,” the moral is in lines 43–44 as Burns laments that people might behave differently if only we could see ourselves in the same way that others see us. The method he chooses to convey this message is by relating the story of Jeany, a young woman sitting in a church service, aware that people are staring at her. Thinking they are admiring her bonnet and her beauty, Jeany is unaware that they really are watching a louse making its way across her bonnet. The narrator believes that lice belong on poor beggars, not on fine ladies. The louse, however, by its presence on Jeany makes the point that nature is indifferent to social status.

“Tam O’Shanter”

Robert Burns sets his folktale “Tam O’Shanter” in his hometown of Alloway. The story tells of a foolish, drunken man who, to his detriment, ignores the good advice of his wife, stays out late drinking too much, and suffers, as does his brave horse Meg, a supernatural encounter.

Video Clip 3

Robert Burns Tam O’Shanter

(click to see video)View a video mini-lecture on “Tam O’Shanter.”

Key Takeaways

- Robert Burns is the National Poet of Scotland because he celebrated his country’s language, folklore, and rural life.

- Burns’s reputation as a natural poet epitomized the Romantic-era ideal of primitivism.

Exercises

- What characteristics of Romantic poetry do you find in “To a Mouse” and “To a Louse”?

- How would you describe the character Tam O’Shanter?

- Who is Maggie (also referred to as Meg)? What did Maggie lose in her flight to save Tam O’Shanter?

- What alerted the witches to Tam’s presence?

- Whom would you describe as the hero of “Tam O’Shanter”?

- What is the “moral” of “Tam O’Shanter”?

- How does Burns’s telling of “Tam O’Shanter” correspond with Romantic ideas about poetry and poets?

Resources

General Information

- The Burns Encyclopedia. Burns Country. Maurice Lindsey.

- “Robert Burns and Radicalism.” The Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution. BBC History.

Biography

- “Burns Timeline.” Robert Burns Birthplace Museum. National Trust for Scotland.

- Robert Burns 1759–1796. National Library of Scotland Digital Gallery.

- Robert Burns, 1759–1796. University of South Carolina Libraries. Rare Books and Special Collections. Biographical information with images of manuscripts.

- Robert Burns Biography. BBC Scotland.

Texts

- Books by Robert Burns. Project Gutenberg.

- Complete Works. Burns Country. includes glossary of Scottish words.

- Selected Poetry of Robert Burns. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

Audio

- “Kevin McFadden Reads ‘To a Mouse’ by Robert Burns.” Poets on Poets. Ed. Tilar Mazzeo. Romantic Circles. General Editors: Neil Fraistat and Steven E. Jones. Technical Editor: Laura Mandell. University of Maryland.

- “Robert Burns 250th Anniversary Collection.” LibriVox.

Video

- “Robert Burns.” Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.

- “Robert Burns, ‘Tam O’Shanter.’” Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.