This is “Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797)”, section 6.5 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

6.5 Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize the unconventional nature of Mary Wollstonecraft’s beliefs, as expressed in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman for her time period.

- Correlate the opinions expressed in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman with the characteristics of Romanticism.

The same philosophy that led to the American Revolution and the French Revolution, the impetus for equality that was a focusing tenet of Romanticism, led many to believe that women should be included in the granting of political and social rights. Although Mary Wollstonecraft wrote novels, she is best remembered for her political treatises such as A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

James Heath (1757–1834), engraved from the painting of John Opie (1761–1807).

Biography

Wollstonecraft’s personal experiences mirror the state of women’s rights in the late 18th/early 19th centuries. As the second child, Mary Wollstonecraft from early childhood resented her elder brother’s education and inheritance. Denied the formal education her brother enjoyed, Wollstonecraft, through her reading, obtained an education equal to or perhaps better than many women of her time period and social class. Because of her father’s declining financial situation, Wollstonecraft earned her own living, working in the only jobs available to women, such as a lady’s companion and a governess, which she found particularly distasteful. Later in her life she attempted to establish schools for girls.

In her personal life as well as her professional life, Wollstonecraft was unconventional and attracted the disdain of traditional society. She gave birth to an illegitimate daughter, allowing people to believe she was married to the child’s father.

Portrait by John Opie.

Wollstonecraft’s two suicide attempts testify to her dissatisfaction with life in a world which disagreed so adamantly with her ideas of radical freedom in moral and social behavior. Later when she became pregnant with William Godwin‘s child, they married, even though both advocated free love without marriage. The couple’s marriage revealed that Wollstonecraft’s first marriage was a pretense, and she again found herself publicly ostracized. Wollstonecraft died from complications of childbirth a month after her daughter with Godwin was born. Their daughter, Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, grew up to marry the poet Shelley and to write the novel Frankenstein.

Text of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

- 1792 A Vindication of the Rights of Women by Mary Wollstonecraft. Great Voyages: The History of Western Philosophy from 1492 to 1776. Bill Uzgalis, Oregon State University. searchable text.

- “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects.” Bartleby.com. rpt. from Boston: Peter Edes, 1792.

- “Modern History Sourcebook: Mary Woolstonecraft [sic]: A Vindication of the Right of Women.” Internet Modern History Sourcebook. Paul Halsall, Fordham University.

- Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft. Project Gutenberg.

- “Wollstonecraft, Mary, 1759–1797 . A Vindication of the Rights of Woman / by Mary Wollstonecraft.” Electronic Text Center. University of Virginia Library.

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

Excerpt from the Introduction

After considering the historic page, and viewing the living world with anxious solicitude, the most melancholy motions of sorrowful indignation have depressed my spirits, and I have sighed when obliged to confess, that either nature has made a great difference between man and man, or that the civilization, which has hitherto taken place in the world, has been very partial. I have turned over various books written on the subject of education, and patiently observed the conduct of parents and the management of schools; but what has been the result? a profound conviction, that the neglected education of my fellow creatures is the grand source of the misery I deplore; and that women in particular, are rendered weak and wretched by a variety of concurring causes, originating from one hasty conclusion. The conduct and manners of women, in fact, evidently prove, that their minds are not in a healthy state; for, like the flowers that are planted in too rich a soil, strength and usefulness are sacrificed to beauty; and the flaunting leaves, after having pleased a fastidious eye, fade, disregarded on the stalk, long before the season when they ought to have arrived at maturity. One cause of this barren blooming I attribute to a false system of education, gathered from the books written on this subject by men, who, considering females rather as women than human creatures, have been more anxious to make them alluring mistresses than rational wives; and the understanding of the sex has been so bubbled by this specious homage, that the civilized women of the present century, with a few exceptions, are only anxious to inspire love, when they ought to cherish a nobler ambition, and by their abilities and virtues exact respect.

In a treatise, therefore, on female rights and manners, the works which have been particularly written for their improvement must not be overlooked; especially when it is asserted, in direct terms, that the minds of women are enfeebled by false refinement; that the books of instruction, written by men of genius, have had the same tendency as more frivolous productions; and that, in the true style of Mahometanism, they are only considered as females, and not as a part of the human species, when improvable reason is allowed to be the dignified distinction, which raises men above the brute creation, and puts a natural sceptre in a feeble hand.

Yet, because I am a woman, I would not lead my readers to suppose, that I mean violently to agitate the contested question respecting the equality and inferiority of the sex; but as the subject lies in my way, and I cannot pass it over without subjecting the main tendency of my reasoning to misconstruction, I shall stop a moment to deliver, in a few words, my opinion. In the government of the physical world, it is observable that the female, in general, is inferior to the male. The male pursues, the female yields—this is the law of nature; and it does not appear to be suspended or abrogated in favour of woman. This physical superiority cannot be denied—and it is a noble prerogative! But not content with this natural pre-eminence, men endeavour to sink us still lower, merely to render us alluring objects for a moment; and women, intoxicated by the adoration which men, under the influence of their senses, pay them, do not seek to obtain a durable interest in their hearts, or to become the friends of the fellow creatures who find amusement in their society.

I am aware of an obvious inference: from every quarter have I heard exclamations against masculine women; but where are they to be found? If, by this appellation, men mean to inveigh against their ardour in hunting, shooting, and gaming, I shall most cordially join in the cry; but if it be, against the imitation of manly virtues, or, more properly speaking, the attainment of those talents and virtues, the exercise of which ennobles the human character, and which raise females in the scale of animal being, when they are comprehensively termed mankind—all those who view them with a philosophical eye must, I should think, wish with me, that they may every day grow more and more masculine.

This discussion naturally divides the subject. I shall first consider women in the grand light of human creatures, who, in common with men, are placed on this earth to unfold their faculties; and afterwards I shall more particularly point out their peculiar designation.

I wish also to steer clear of an error, which many respectable writers have fallen into; for the instruction which has hitherto been addressed to women, has rather been applicable to LADIES, if the little indirect advice, that is scattered through Sandford and Merton, be excepted; but, addressing my sex in a firmer tone, I pay particular attention to those in the middle class, because they appear to be in the most natural state. Perhaps the seeds of false refinement, immorality, and vanity have ever been shed by the great. Weak, artificial beings raised above the common wants and affections of their race, in a premature unnatural manner, undermine the very foundation of virtue, and spread corruption through the whole mass of society! As a class of mankind they have the strongest claim to pity! the education of the rich tends to render them vain and helpless, and the unfolding mind is not strengthened by the practice of those duties which dignify the human character. They only live to amuse themselves, and by the same law which in nature invariably produces certain effects, they soon only afford barren amusement.

But as I purpose taking a separate view of the different ranks of society, and of the moral character of women, in each, this hint is, for the present, sufficient; and I have only alluded to the subject, because it appears to me to be the very essence of an introduction to give a cursory account of the contents of the work it introduces.

My own sex, I hope, will excuse me, if I treat them like rational creatures, instead of flattering their FASCINATING graces, and viewing them as if they were in a state of perpetual childhood, unable to stand alone. I earnestly wish to point out in what true dignity and human happiness consists—I wish to persuade women to endeavour to acquire strength, both of mind and body, and to convince them, that the soft phrases, susceptibility of heart,

delicacy of sentiment, and refinement of taste, are almost synonymous with epithets of weakness, and that those beings who are only the objects of pity and that kind of love, which has been termed its sister, will soon become objects of contempt.

Dismissing then those pretty feminine phrases, which the men condescendingly use to soften our slavish dependence, and despising that weak elegancy of mind, exquisite sensibility, and sweet docility of manners, supposed to be the sexual characteristics of the weaker vessel, I wish to show that elegance is inferior to virtue, that the first object of laudable ambition is to obtain a character as a human being, regardless of the distinction of sex; and that secondary views should be brought to this simple touchstone.

This is a rough sketch of my plan; and should I express my conviction with the energetic emotions that I feel whenever I think of the subject, the dictates of experience and reflection will be felt by some of my readers. Animated by this important object, I shall disdain to cull my phrases or polish my style—I aim at being useful, and sincerity will render me unaffected; for wishing rather to persuade by the force of my arguments, than dazzle by the elegance of my language, I shall not waste my time in rounding periods, nor in fabricating the turgid bombast of artificial feelings, which, coming from the head, never reach the heart. I shall be employed about things, not words! and, anxious to render my sex more respectable members of society, I shall try to avoid that flowery diction which has slided from essays into novels, and from novels into familiar letters and conversation.

These pretty nothings, these caricatures of the real beauty of sensibility, dropping glibly from the tongue, vitiate the taste, and create a kind of sickly delicacy that turns away from simple unadorned truth; and a deluge of false sentiments and over-stretched feelings, stifling the natural emotions of the heart, render the domestic pleasures insipid, that ought to sweeten the exercise of those severe duties, which educate a rational and immortal being for a nobler field of action.

The education of women has, of late, been more attended to than formerly; yet they are still reckoned a frivolous sex, and ridiculed or pitied by the writers who endeavour by satire or instruction to improve them. It is acknowledged that they spend many of the first years of their lives in acquiring a smattering of accomplishments: meanwhile, strength of body and mind are sacrificed to libertine notions of beauty, to the desire of establishing themselves, the only way women can rise in the world—by marriage. And this desire making mere animals of them, when they marry, they act as such children may be expected to act: they dress; they paint, and nickname God’s creatures. Surely these weak beings are only fit for the seraglio! Can they govern a family, or take care of the poor babes whom they bring into the world?

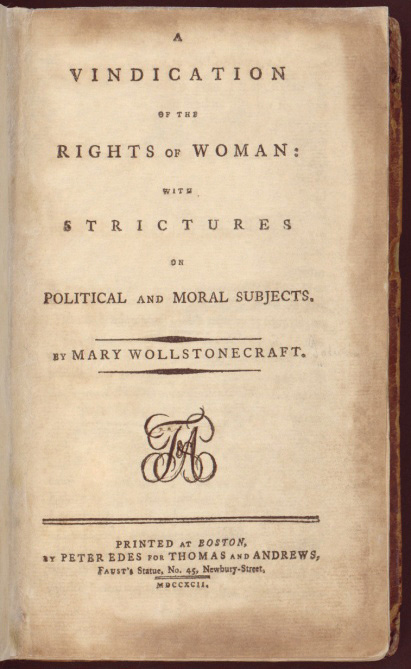

Title page from the first American edition 1792.

Key Takeaways

- Because of the strictures of her society, Mary Wollstonecraft was largely self-educated and forced to work in traditional women’s jobs which she disliked.

- Wollstonecraft evinces the Romantic characteristics of primitivism and individualism as well as exemplifying tenets from Wordsworth’s Preface to Lyrical Ballads such as the use of common language and writing for and about common people.

Exercises

- In the first paragraph of A Vindication, Wollstonecraft uses an analogy to illustrate the thesis of her essay: she compares women as they are treated by society to flowers. What is the purpose of this analogy?

- This analogy leads her to the thesis of her essay. Identify her thesis.

- In paragraph six, Wollstonecraft specifies her audience. To what group of women is she writing? Why does she choose that group of women?

- How, in paragraph 8, does Wollstonecraft say women usually are treated, and how does she plan to be different?

- What type of language does Wollstonecraft intend to use in her essay? Compare her choice of language to that advocated by Wordsworth in his 1802 Preface to Lyrical Ballads.

- Wollstonecraft argues that because women are not educated they have only one means to “rise in the world.” What is that means?

Resources

General Information

- “Wollstonecraft’s Rights of Woman.” Taking Liberties: The Struggle for Britain’s Freedoms and Rights. British Library.

Biography

- “Mary Wollstonecraft.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Sylvana Tomaselli, Stanford University.

- “Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797).” Shelley’s Ghost: Reshaping the Image of a Literary Family. Bodleian Libraries. Oxford University Exhibit in partnership with the New York Public Library.

- “Mary Wollstonecraft, 1759–1797.” The History Guide. Steven Kreis. Lectures on Modern European Intellectual History.

- “Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797).” Chawton House Library. Valerie Patten. Library and Early Women’s Writing. Women Writers.

- “Mary Wollstonecraft: A ‘Speculative and Dissenting Spirit.’” Janet Todd, University of Glasgow. British History. BBC History. BBC.

- “Wollstonecraft Time Line.” Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797). Bill Uzgalis, Oregon State University.

Text

- 1792 A Vindication of the Rights of Women by Mary Wollstonecraft. Great Voyages: The History of Western Philosophy from 1492 to 1776. Bill Uzgalis, Oregon State University. searchable text.

- “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects.” Bartleby.com. rpt. from Boston: Peter Edes, 1792.

- “Modern History Sourcebook: Mary Woolstonecraft [sic]: A Vindication of the Rights of Women.” Internet Modern History Sourcebook. Paul Halsall, Fordham University.

- Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft. Project Gutenberg.

- “Wollstonecraft, Mary, 1759–1797 . A Vindication of the Rights of Woman / by Mary Wollstonecraft.” Electronic Text Center. University of Virginia Library.

Audio

- Mary Wollstonecraft’s Last Three Notes to Godwin. Shelley’s Ghost: Reshaping the Image of a Literary Family. Bodleian Libraries. Oxford University Exhibit in partnership with the New York Public Library. podcast read by Oxford University students.

- Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication. Shelley’s Ghost: Reshaping the Image of a Literary Family. Bodleian Libraries. Oxford University Exhibit in partnership with the New York Public Library. podcast read by Oxford University students.

- A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. LibriVox.

- A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Shelley’s Ghost: Reshaping the Image of a Literary Family. Bodleian Libraries. Oxford University Exhibit in partnership with the New York Public Library. podcast read by Oxford University students.

- A Vindication of the Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft. Project Gutenberg.

- “Wollstonecraft and Women’s Rights.” Taking Liberties: The Struggle for Britain’s Freedoms and Rights. Barbara Taylor. British Library. lecture on Wollstonecraft’s influence on British political rights for women.

Women’s Rights

- Introduction. Abby Wolf, Harvard University. 19th Century Women Writers. PBS.

- “Women’s Lives in Eighteenth Century England.” Miami University, Oxford, Ohio.

- “Wollstonecraft and Women’s Rights.” Taking Liberties: The Struggle for Britain’s Freedoms and Rights. Barbara Taylor. British Library. lecture on Wollstonecraft’s influence on British political rights for women.