This is “William Blake (1757–1827)”, section 6.3 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

6.3 William Blake (1757–1827)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Recognize William Blake as both artist and writer, and assess the integration of his writing with his art.

- Interpret Blake’s title Songs of Innocence and Experience, and differentiate the state of innocence and the state of experience in the correlating pairs of poems.

- Evaluate Songs of Innocence and Experience as examples of Romantic poetry.

Biography

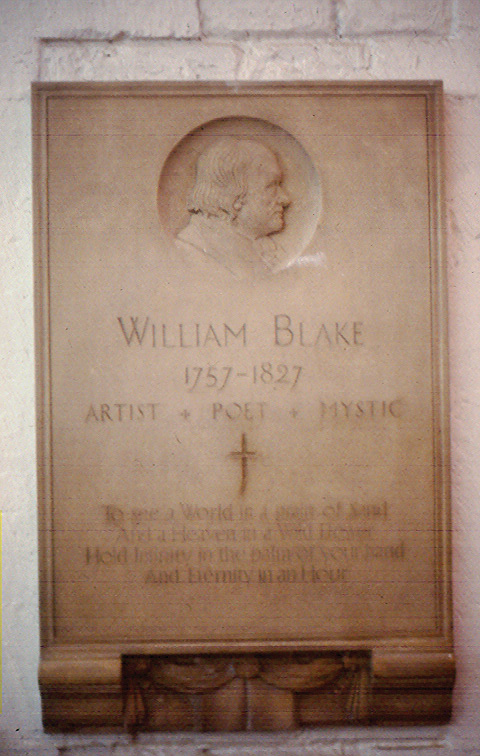

William Blake‘s memorial plaque in St. Paul’s Cathedral, London, identifies him as an “artist, poet, mystic.” Born in London, where he spent most of his life, Blake was educated largely at home. From his childhood he claimed to experience visions of and even conversations with angels and with the Virgin Mary. His visionary experiences appear in many of his poetic works, such as The Book of Urizen and The Book of Los.

For a short time, Blake attended art school and then was apprenticed to an engraver. He made his living primarily from his artwork. His poetry, such as Songs of Innocence and Experience, was written as an integral part of his engravings.

William Blake Memorial Plaque

William Blake’s memorial plaque in St. Paul’s Cathedral, London including the first stanza of Blake’s “Auguries of Innocence.”

William Blake

1757–1827

Artist + Poet + Mystic

“To see a world in a grain of sand

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand

And eternity in an hour.”

The British Library includes Blake’s Notebook in its Virtual Books collection. On pages 29 and 30, you can see a draft copy of “The Tyger” and on page 3, sketches of tigers. The William Blake Archive provides digital images of Songs of Innocence and Experience and of Blake’s other poetic works that allow you to read the works as Blake intended, with the accompanying engravings.

Texts

- The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Blake Digital Text Project. David V. Erdman, ed. Nelson Hilton. University of Georgia, Athens.

- Selected Poetry of William Blake. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English. University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- Songs of Innocence and Experience by William Blake. Project Gutenberg.

Illustrated Text

- “Songs of Innocence 1789.” The William Blake Archive. Editors: Morris Eaves, University of Rochester; Robert Essick, University of California, Riverside; Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library of Congress.

- “Songs of Innocence and Experience.” The William Blake Archive. Editors: Morris Eaves, University of Rochester; Robert Essick, University of California, Riverside; Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library of Congress.

- “William Blake Online.” Tate Britain.

Songs of Innocence and Experience

Although Blake is considered a pre-Romantic poet, his poetry exhibits many of the characteristics of Romantic poetry.

Like many late 18th-century and 19th-century writers, Blake abhorred the effects the Industrial Revolution had on the physical environment and, more importantly, on the people caught in a time of radical change in the ways of living and making a living their families had pursued for generations. Child labor issues figure prominently in Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience. The Victorian Web’s section on child labor includes testimony from 1819 Parliamentary hearings on the Chimney Sweepers’ Regulation Bill. With his Romantic sensibility, Blake puts a human face on the debate, encouraging the reader to think of the situation in terms of individuals—Tom, Dick, Joe, Ned, and Jack—innocent children living lives of inhumane hardship.

Key Takeaways

- William Blake created his poetry as an integral part of his artwork.

- Blake’s title pinpoints the dichotomy between the states of innocence and of experience that, according to the work’s subtitle, characterize the human soul.

- Although often considered a pre-Romantic poet, Blake’s work exemplifies many characteristics of Romantic poetry.

Exercises

-

Blake titles his collection of poems Songs of Innocence and Experience. His subtitle explains that the poems are “Shewing [showing] the Two Contrary [opposite] States of the Human Soul.” Both “innocence” and “experience” are part of each human soul.

- What do you think he means when he uses the terms “innocence” and “experience”?

- Do “innocence” and “experience” belong to certain ages of a person’s life, or to one’s attitude about life, or to the experiences that happen to a person in life, or other circumstances?

-

After reading all of the Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience, re-read the following pairs of poems as companion poems:

- “The Lamb” and “The Tyger”

- “The Chimney Sweeper” and “The Chimney Sweeper”

- “Holy Thursday” and “Holy Thursday”

- “Nurse’s Song” and “Nurse’s Song”

Why does the first poem of each pair belong in the innocence category and the second in the experience category?

- While “The Lamb” is a question and answer poem, its companion “The Tyger” is only a question poem. Why?

-

In “The Lamb,” who does the speaker refer to in the following lines?

He is called by thy name,

For he calls himself a Lamb:

He is meek & he is mild,

He became a little child:

- In the Innocence “The Chimney Sweeper,” why does Tom dream of being locked in “coffins of black”? Note how the young boys imagine Heaven; how does this add to the pathos of the poem? Explain the final line of the poem: “So if all do their duty they need not fear harm”; to whom does the speaker refer with the word “all”?

- In the Experience “The Chimney Sweeper,” who does the boy seem to blame for his situation?

-

In the Innocence “Holy Thursday,” the poem describes an apparently beautiful sight: the poor children of London cleaned up and dressed in their best clothing being marched to a church service to sing praises. In the Experience “Holy Thursday,” the poem begins with a question:

Is this a holy thing to see

In a rich and fruitful land,

Babes reduced to misery,

Fed with cold and usurous hand?

What is the relationship of the two poems?

- What characteristics of Romanticism do you find in Songs of Innocence and Experience?

Resources

General Information

- The William Blake Archive. Editors: Morris Eaves, University of Rochester; Robert Essick, University of California, Riverside; Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library of Congress.

Biography

- “About Blake.” The Blake Society.

- “Chronology.” The William Blake Archive. Editors: Morris Eaves, University of Rochester; Robert Essick, University of California, Riverside; Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library of Congress.

- William Blake (1757–1827). The British Museum.

- “William Blake (1757–1827).” Denise Vultee. The William Blake Archive. Editors: Morris Eaves, University of Rochester; Robert Essick, University of California, Riverside; Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library of Congress.

Songs of Innocence and Experience

- Blake, Songs of Innocence and Experience, 1794. British Library.

Texts

- The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Blake Digital Text Project. David V. Erdman, ed. Nelson Hilton, University of Georgia, Athens.

- Selected Poetry of William Blake. Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire. Department of English. University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- Songs of Innocence and Experience by William Blake. Project Gutenberg.

Illustrated Texts

- “Songs of Innocence 1789.” The William Blake Archive. Editors: Morris Eaves, University of Rochester; Robert Essick, University of California, Riverside; Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library of Congress.

- “Songs of Innocence and Experience.” The William Blake Archive. Editors: Morris Eaves, University of Rochester; Robert Essick, University of California, Riverside; Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library of Congress.

- “William Blake Online.” Tate Britain.

Audio

- Allen Ginsberg Performing William Blake. Naropa University Archive Project. Internet Archive.

- Songs of Innocence and Experience. LibriVox.

- Songs of Innocence and Experience by Blake. Project Gutenberg.

- “Stefanie Wortman Reads ‘The Chimney Sweeper’ [from Songs of Experience] by William Blake.” Poets on Poets. Ed. Tilar Mazzeo. Romantic Circles. General Editors: Neil Fraistat and Steven E. Jones. Technical Editor: Laura Mandell. University of Maryland. audio and text.

- “William Blake.” The Romantics. BBC. selected poems.

Art Information

- “Blake’s Notebooks.” Virtual Books. British Library.

- “Illuminated Printing.” The William Blake Archive. Editors: Morris Eaves, University of Rochester; Robert Essick, University of California, Riverside; Joseph Viscomi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library of Congress.

- “William Blake and the Illuminated Book.” The Electronic Labyrinth. Christopher Keep, Tim McLaughlin, Robin Parmar. Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities. University of Virginia.

Concordance

- Concordance to The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Blake Digital Text Project. Nelson Hilton, University of Georgia, Athens.

- “William Blake Songs of Innocence and Experience Web Concordance.” The Web Concordances.