This is “The Effect of Income Taxes on Capital Budgeting Decisions”, section 8.7 from the book Accounting for Managers (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

8.7 The Effect of Income Taxes on Capital Budgeting Decisions

Learning Objective

- Understand the impact that income taxes have on capital budgeting decisions.

Question: Throughout the chapter, we assumed no income taxes were involved. This is a reasonable assumption for not-for-profit entities and governmental agencies. However, firms that pay income taxes must consider the impact income taxes have on cash flows for long-term investments. How do for-profit organizations include income taxes in their analysis when making long-term investment decisions?

Answer: Let’s look at an example to help explain how this works. The management of Scientific Products, Inc. (SPI), is considering a five-year contract to build scientific instruments for a large school district. The initial investment required to purchase production equipment is $400,000 (to be depreciated over 5 years using the straight-line method, with no salvage value). An additional $50,000 in working capital is required for the contract. Working capital will be returned to SPI at the end of five years. Annual net cash receipts from daily operations (cash receipts minus cash payments) are shown as follows. Since depreciation expense is not a cash outflow, it is not included in these amounts.

| Year 1 | $ 50,000 |

| Year 2 | $ 60,000 |

| Year 3 | $120,000 |

| Year 4 | $200,000 |

| Year 5 | $130,000 |

Management established a required rate of return of 10 percent for this proposal. The company’s tax rate is 40 percent. (The complexities of government tax codes have a significant impact on the tax rate used. For simplicity, we use a tax rate of 40 percent for this example.)

When taxes are involved, it is important to understand which cash flows are affected by the tax rate and which are not. We look at this by addressing the following capital budgeting items:

- Investment cash outflows

- Working capital cash outflows and inflows

- Revenue cash inflows and expense cash outflows

- Depreciation

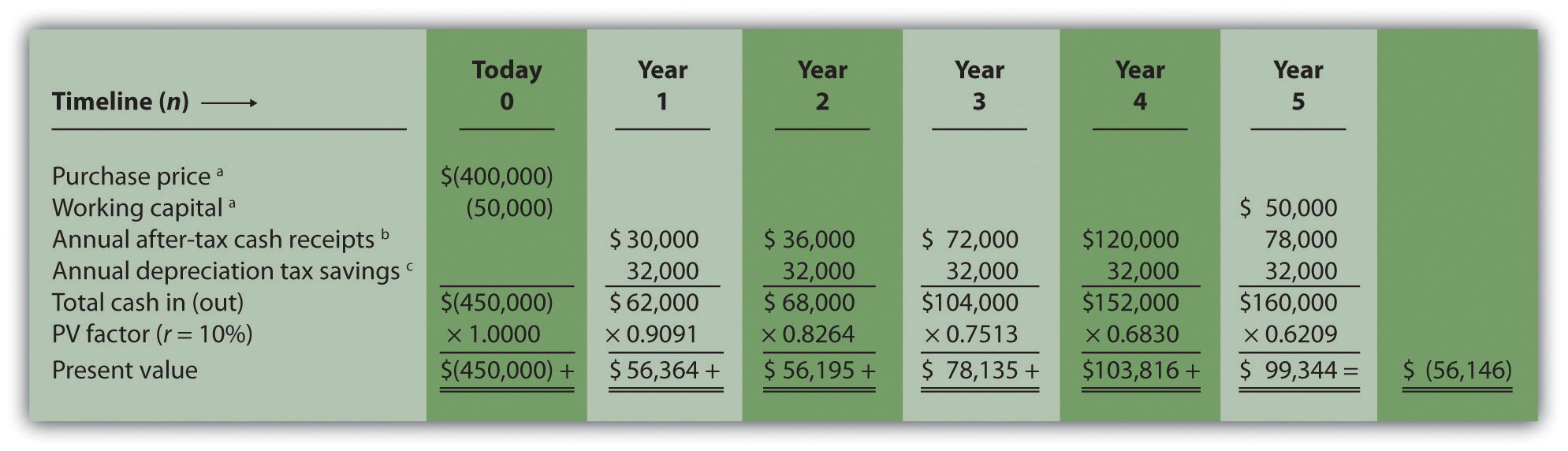

Figure 8.7 "NPV Calculation with Income Taxes for Scientific Products, Inc." provides a detailed example of how companies adjust for income taxes when evaluating long-term investments. Examine Figure 8.7 "NPV Calculation with Income Taxes for Scientific Products, Inc." carefully, including the footnotes, as we explain each of these items.

Figure 8.7 NPV Calculation with Income Taxes for Scientific Products, Inc.

Note: the NPV is $(56,146).

Since NPV is < 0, reject the investment. (The investment provides a return less than 10 percent.)

a Initial investment purchase price and working capital do not directly affect net income and therefore are not adjusted for income taxes.

b Amount equals net cash receipts before taxes × (1 – tax rate). For year 1, $30,000 = $50,000 × (1 – 0.40); for year 2, $36,000 = $60,000 × (1 – 0.40); and so forth.

c Depreciation tax savings = Depreciation expense × Tax rate. Depreciation expense is $80,000 (= $400,000 cost ÷ 5 year useful life). Thus annual depreciation tax savings is $32,000 (= $80,000 depreciation expense × 0.40 tax rate).

- Investment Cash Outflows. The initial investment in production equipment of $400,000 is not adjusted for income taxes because it does not directly affect net income. Thus this amount is included in full in Figure 8.7 "NPV Calculation with Income Taxes for Scientific Products, Inc.".

- Working Capital Cash Outflows and Inflows. Working capital of $50,000 is not adjusted for income taxes since it does not affect net income. Thus this amount is included in full as a cash outflow at the beginning of the project and again in full when returned to the company at the end of the project, as shown in Figure 8.7 "NPV Calculation with Income Taxes for Scientific Products, Inc.".

-

Revenues and Expenses. When a company must pay income taxes, all revenue cash inflows and expense cash outflows affect net income and therefore affect income taxes paid. The goal is to determine the after-tax cash flow. This is calculated in the equation that follows.

The tax rate for Scientific Products, Inc., is 40 percent. Thus net cash receipts (revenue cash inflows minus expense cash outflows) are multiplied by 0.60 (= 1 – 0.40). This results in an after-tax cash flow, as shown in Figure 8.7 "NPV Calculation with Income Taxes for Scientific Products, Inc.".

Key Equation

After-tax revenue cash inflow = Before-tax cash inflow × (1 – tax rate) After-tax expense cash outflow = Before-tax cash outflow × (1 – tax rate)- Depreciation. Although depreciation expense is not a cash outflow, it does reduce taxable income and thereby reduces taxes that are paid (recall that the entry to record depreciation for financial accounting purposes does not affect cash; debit depreciation expense and credit accumulated depreciation). The term used to describe this tax savings is depreciation tax shieldThe tax savings that result from depreciation expense.. The tax savings resulting from depreciation are calculated as follows:

Key Equation

Depreciation tax savings cash inflow = Depreciation expense × Tax rateThe production equipment, which has a purchase price of $400,000, has a useful life of 5 years and no salvage value. SPI uses the straight-line method, which depreciates the original cost evenly over the useful life of the asset. Thus depreciation expense is $80,000 (= $400,000 ÷ 5 years). This is multiplied by the tax rate of 40 percent to get the annual tax savings of $32,000 (= $80,000 × 0.40), as shown in Figure 8.7 "NPV Calculation with Income Taxes for Scientific Products, Inc.".

Question: Based on the information presented in Figure 8.7 "NPV Calculation with Income Taxes for Scientific Products, Inc.", should SPI accept the investment proposal?

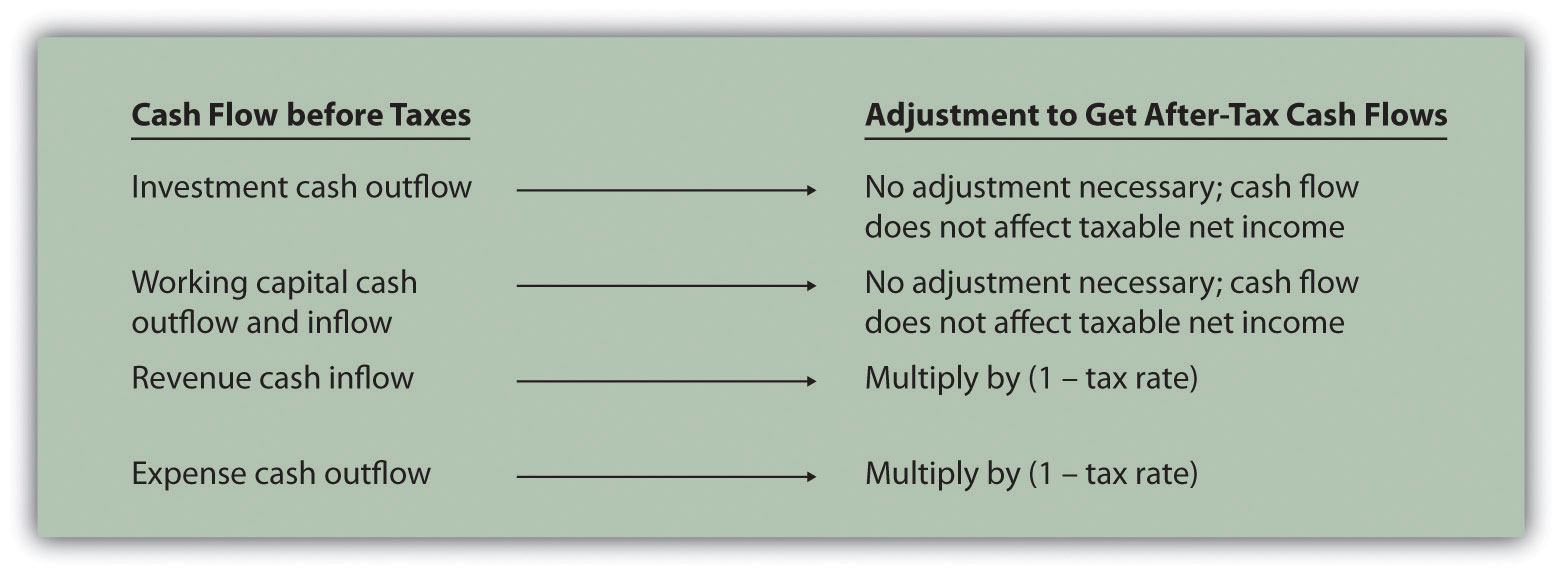

Answer: As you can see in Figure 8.7 "NPV Calculation with Income Taxes for Scientific Products, Inc.", the NPV is negative ($[56,146]), so SPI’s management should reject the investment proposal. Figure 8.8 "How Income Taxes Affect Capital Budgeting Cash Flows" provides a summary of how income taxes influence cash flows for long-term investments. (Note that this section is intended to give you a general overview of how income taxes effect capital budgeting decisions. Finance textbooks provide more detail regarding how to adjust cash flows for income taxes in more complex situations.)

Figure 8.8 How Income Taxes Affect Capital Budgeting Cash Flows

Key Takeaway

- Companies that pay income taxes must consider the impact income taxes have on cash flows for long-term investments, and make the necessary adjustments. Investment and working capital cash flows are not adjusted because these cash flows do not affect taxable income. Revenue cash inflows and expense cash outflows are adjusted by multiplying the cash flow by (1 – tax rate). Although depreciation expense is not a cash outflow, it provides tax savings. The tax savings is calculated by multiplying depreciation expense by the tax rate. Once these adjustments are made, we can calculate the NPV and IRR.

Review Problem 8.7

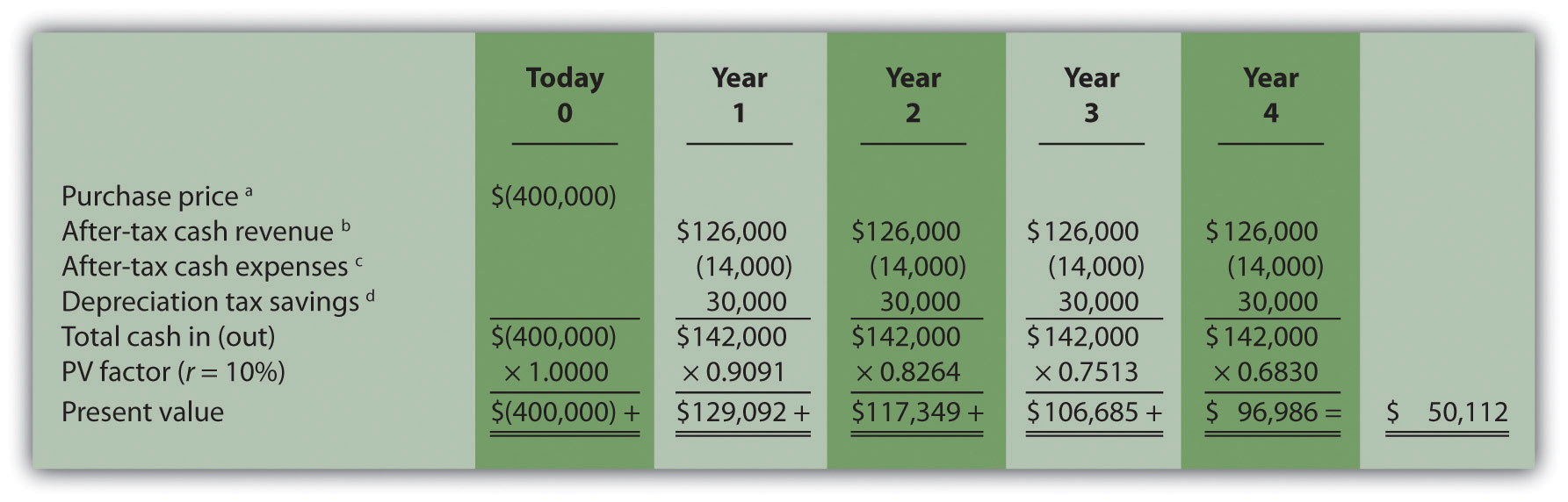

Car Repair, Inc., would like to purchase a new machine for $400,000. The machine will have a life of 4 years with no salvage value, and is expected to generate annual cash revenue of $180,000. Annual cash expenses, excluding depreciation, will total $20,000. The company uses the straight-line depreciation method, has a tax rate of 30 percent, and requires a 10 percent rate of return.

- Find the NPV of this investment using the format presented in Figure 8.7 "NPV Calculation with Income Taxes for Scientific Products, Inc.".

- Should the company purchase the machine? Explain.

Solution to Review Problem 8.7

-

The NPV is $50,112 as shown in the following figure.

a Initial investment purchase price does not directly affect net income and therefore is not adjusted for income taxes.

b Amount equals cash revenue before taxes × (1 – tax rate); $126,000 = $180,000 × (1 – 0.30).

c Amount equals cash expense before taxes × (1 – tax rate); $14,000 = $20,000 × (1 – 0.30).

d Depreciation tax savings = Depreciation expense × Tax rate. Depreciation expense is $100,000 (= $400,000 cost ÷ 4 year useful life). Thus annual depreciation tax savings is $30,000 (= $100,000 depreciation expense × 0.30 tax rate).

- Yes, the company should purchase the machine. The positive NPV of $50,112 shows the return of this proposal is above the company’s required rate of return of 10 percent.