This is “Academic Writing”, chapter 11 from the book Writers' Handbook (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 11 Academic Writing

Writing as a College Student

As a college student, you have been writing for years, so you probably think that you have a clear understanding about academic writing. High school and college writing, however, differ in many ways. This chapter will present some of those core differences along with a general overview of the college writing process.

11.1 Meeting College Writing Expectations

Learning Objectives

- Understand and describe differences between high school and college writing.

- Recognize some of the core principles and values of higher education.

If you’re like most first-year college students, you’re probably anxious about your first few writing assignments. Transitioning from being a successful high school writer to being a quality college writer can be difficult. You have to adjust to different learning cultures. You have to accept that college writing is different from high school writing and come to understand how it is different.

These students relay a typical range of first-year college experiences:

Emma: I always got As on my high school papers, so I thought I was a good writer until I came to college and had to completely rewrite my first paper to get a C–.

Javier: I received an F on my first college paper because I “did not include one original thought in the whole paper.” I thought I was reporting on information I had researched. I didn’t know that I was supposed to add my own thoughts. Luckily, the professor had a policy to throw out each student’s lowest grade of the semester.

Danyell: The professor in my Comp 101 class said that he didn’t want us turning in anything meaningless or trite. He said that we were to show him that we had critical thought running through our heads and knew how to apply it to the readings we found in our research. I had no idea what he was talking about.

Pat: I dreaded my first college English class since I had never done well in English classes in high school. Writing without grammatical and mechanical errors is a challenge for me, and my high school teachers always gave me low grades on my papers due to all my mistakes. So I was surprised when I got a B+ on my first college paper, and the professor had written, “Great paper! You make a solid argument. Clean up your grammar and mechanics next time and you will get an A!” Suddenly it seemed that there was something more important than grammar and punctuation!

What’s “Higher” about Higher Education?

Despite the seeming discrepancy between what high school and college teachers think constitutes good college writing, there is an overall consensus about what is “higher” about higher education.

Thinking with flexibility, depth, awareness, and understanding, as well as focusing on how you think, are some of the core building blocks that make higher education “higher.” These thinking methods coupled with perseverance, independence, originality, and a personal sense of mission are core values of higher education.

Differences between High School and College Culture

The difference between high school and college culture is like the difference between childhood and adulthood. Childhood is a step-by-step learning process. Adulthood is an independent time when you use the information you learned in childhood. In high school culture, you were encouraged to gather knowledge from teachers, counselors, parents, and textbooks. As college students, you will rely on personal assistance from authorities less and less as you learn to analyze texts and information independently. You will be encouraged to collaborate with others, but more to discuss ideas and concepts critically than to secure guidance.

How the Writing Process Differs in College

It’s important to understand that no universal description of either high school or college writing exists. High school teachers might concentrate on skills they want their students to have before heading to college: knowing how to analyze (often literary) texts, to develop the details of an idea, and to organize a piece of writing, all with solid mechanics. A college teacher might be more concerned with developing students’ ability to think, discuss, and write on a more abstract, interdisciplinary level. But there are exceptions, and debates rage on about where high school writing ends and college writing begins.

Key Takeaways

- Requirements and expectations for high school and college writing vary greatly from high school to high school and college to college.

- Some general differences, however, are fairly consistent: College students are expected to function more independently than high school students are. College students are encouraged to think with a deep awareness, to develop a clear sense of how they think, and to think on a more abstract level.

Exercises

- Write a brief essay or a journal or blog entry about your personal experience with higher education so far. Consider, especially, what sort of misconceptions you have discovered as you compare your expectations with reality.

-

Study the following two sets of writing standards. The first is the result of a recent nationwide project to create core standards for language arts students in eleventh and twelfth grades. It outlines what students should be able to do by the time they graduate high school. The second describes what college writing administrators have agreed students should be able to do by the time they finish their first year of college writing courses. What differences do you see? What might account for those differences? How well do you think your skills match up with each set of standards?

- Common Core State Standards Initiative English Language Arts Standards for Grades 11 and 12: http://www.corestandards.org/the-standards/english-language-arts-standards/writing-6-12/grade-11-12

- Council of Writing Program Administrators (WPA) Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition: http://www.wpacouncil.org/positions/outcomes.html

11.2 Using Strategies for Writing College Essays

Learning Objectives

- Use time-management skills to lay out a work plan for major writing assignments.

- Develop strategies for reading college assignments strategically.

As a college student, you must take complete responsibility for your writing assignments. Your professors are assessing your ability to think for yourself, so they’re less likely to give you ready-made templates on how to write a given essay. This lack of clarity will be unsettling, but it’s part of an important growth process. By using strategies, you can systematically approach each assignment and gather the information you need for your writing requirements.

Plotting a Course for Your Writing Project

Once you know you have an upcoming writing project, you have some basic decisions to make. The following list of questions will lead you to make some preliminary choices for your writing project. (To learn more, see Chapter 5 "Planning", Section 5.3 "Developing Your Purposes for Writing".)

- What am I trying to accomplish? Writing can serve a variety of purposesA writer’s reason for writing (e.g., to inform, to entertain)., such as to explain, to persuade, to describe, to entertain, or to compare. Your assignment might specifically dictate the purpose of the writing project. Or the assignment might simply indicate, for example, that you are to show you understand a topic. In such a situation, you would then be free to choose a writing purpose through which you could demonstrate your understanding.

- Who do I want my readers to be? Traditionally the audienceThe people to whom a piece of communication is directed. for a college student’s paper has been the instructor, but technology is rapidly changing that. Many instructors actively make use of the web’s collaborative opportunities. Your fellow students (or even people outside the class) may now be your audience, and this will change how you approach your assignment. Even if your instructor is the only person who will see your finished product, you have the right (and even the responsibility) to identify an ideal reader or readership for your work. Whoever your audience is, take care to avoid writing too far above or too far beneath their knowledge or interest level.

- What am I writing about? Your topicThe content area of a piece of communication. might be set by your instructor. If so, make sure you know if you have the option of writing about different angles of the topic. If the topic is not preset, choose a topic in which you will be happy to immerse yourself.

- What’s my position on this topic? Analyze your ideas and opinions before you start the writing project, especially if the assignment calls for you to take a position. Leave room for new ideas and changes in your opinion as you research and learn about the topic. Keep in mind that taking a stand is important in your efforts to write a paper that is truly yours rather than a compilation of others’ ideas and opinions, but the stand you take should evolve from encounters with the opinions of others. Monitor your position as you write your first draft, and attend to how it changes over the course of your writing and reading. If your purpose is to compare ideas and opinions on a given topic, clarifying your opinion may not be so critical, but remember that you are still using an interpretive point of view even when you are “merely” summarizing or analyzing data.

- How long does this piece of writing need to be? How much depth should I go into? Many assignments have a predetermined range of page numbers, which somewhat dictates the depth of the topic. If no guidance is provided regarding length, it will be up to you to determine the scope of the writing project. Discussions with other students or your instructor might be helpful in making this determination.

- How should I format this piece of writing? In today’s digital world, you have several equally professional options for completing and presenting your writing assignments. Unless your professor dictates a specific method for awareness and learning purposes, you will probably be free to make these format choices. Even your choice of font can be significant.

- How or where will I publish this piece of writing? You are “publishing” every time you place an essay on a course management system or class-wide wikiAn interactive, shared website featuring content that can be edited by many users. or blogShort for weblog, a regularly posted entry on the web, and usually managed by a single person or a group of like-minded writers., or even when you present an essay orally. More likely than not, if your writing means something to you, you will want to share it with others beyond your instructor in some manner. Knowing how you will publish your work will affect some of the choices you make during the writing process.

- How should my writing look beyond questions of format and font? College essays used to be completely devoid of visuals. Nowadays, given the ease of including them, an essay that does not include visuals might be considered weak. On the other hand, you do not want to include a visual just for the sake of having one. Every visual must be carefully chosen for its value-adding capacity. (To learn more about visuals, see Chapter 9 "Designing", Section 9.3 "Incorporating Images, Charts, and Graphs".)

Planning the basics for your essay ahead of time will help assure proper organization for both the process and the product. It is almost a certainty that an unorganized process will lead to an unorganized product.

Reading Assignments Closely and Critically

A close and careful reading of any given writing assignment will help you sort out the ideas you want to develop in your writing assignment and make sense of how any assigned readings fit with the required writing.

Use the following strategies to make the most of every writing assignment you receive:

- Look for key words, especially verbs such as analyze, summarize, evaluate, or argue, in the assignment itself that will give clues to the genreA type of communication determined by its function with formal characteristics and conventions developed over time., structureThe form or organization of a piece of writing., and mediumThe means through which a message is transmitted. of writing required.

- Do some prewriting that establishes your base of knowledge and your initial opinions about the subject if the topic is predetermined. Make a list of ideas you will need to learn more about in order to complete the assignment.

- Develop a list of possible ideas you could pursue if the topic is more open. (For more about choosing a topic, see Chapter 5 "Planning", Section 5.1 "Choosing a Topic".)

Use the following strategies to help you make the most of readings that support the writing assignment:

- Make a note if you question something in any assigned reading related to the writing assignment.

- Preview each reading assignment by jotting down your existing opinions about the topic before reading. As you read, monitor whether your preconceived opinions prevent you from giving the text a fair reading. After finishing the text, check for changes in your opinions as result of your reading.

- Mark the locations of different opinions in your readings, so you can easily revisit them. (For more on how this works with research, see Chapter 7 "Researching", Section 7.8 "Creating an Annotated Bibliography".)

- Note the points in your readings that you consider most interesting and most useful. Consider sharing your thoughts on the text in class discussions.

- Note any inconsistencies or details in your readings with which you disagree. Plan to discuss these details with other students or your professor.

Above all, when questions or concerns arise as you apply these strategies, take them up with your professor directly, either in class or during office hours. Making contact with your professor by asking substantive questions about your reading and writing helps you stand out from the crowd and demonstrates that you are an engaged student.

Connecting Your Reading with Your Writing

College writing often requires the use of others’ opinions and ideas to support, compare, and ground your opinions. You read to understand others’ opinions; you write to express your opinions in the context of what you’ve read. Remember that your writing must be just that—yours. Take care to use others’ opinions and ideas only as support. Make sure your ideas create the core of your writing assignments. (For more on documentation, see Chapter 22 "Appendix B: A Guide to Research and Documentation", Section 22.5 "Developing a List of Sources".)

Sharing and Testing Your Thinking with Others

Discussion and debate are mainstays of a college education. Sharing and debating ideas with instructors and other students allows all involved to learn from each other and grow. You often enter into a discussion with your opinions and exit with a widened viewpoint. Although you can read an assignment and generate your understandings and opinions without speaking to another person, you would be limiting yourself by those actions. Instead it is in your best interest to share your opinions and listen to or read others’ opinions on a steady, ongoing basis.

In order to share your ideas and opinions in a scholarly way, you must properly prepare your knowledge bank. Reading widely and using the strategies laid out in the Section 11.2.3 "Connecting Your Reading with Your Writing" are excellent methods for developing that habit.

Make sure to maintain fluidity in your thoughts and opinions. Be prepared to make adjustments as you learn new ideas through discussions with others or through additional readings. You can discuss and debate in person or online, in real time or asynchronously. One advantage to written online discussions and debates is that you have an archived copy for later reference, so you don’t have to rely on memory. For this reason, some instructors choose to develop class sites for student collaboration, discussion, and debate.

Key Takeaways

- The assignments you receive from your instructors in college are as worthy of a close and careful reading as any other texts you are assigned to read. You can learn to employ certain strategies to get the most out of the assignments you are being asked to perform.

- Success in college and life depends on time- and project-management skills: being able to break large projects into smaller, manageable tasks and learning how to work independently and collaboratively.

Exercise

For every assignment you receive with an open topic, get into the habit of writing a journal or blog entry that answers the following four questions:

- What are some topics that interest you?

- What topics will fit within the time frame you have for the project?

- Of the possible topics, which have enough depth for the required paper?

- For which topics can you think of an angle about which you are passionate?

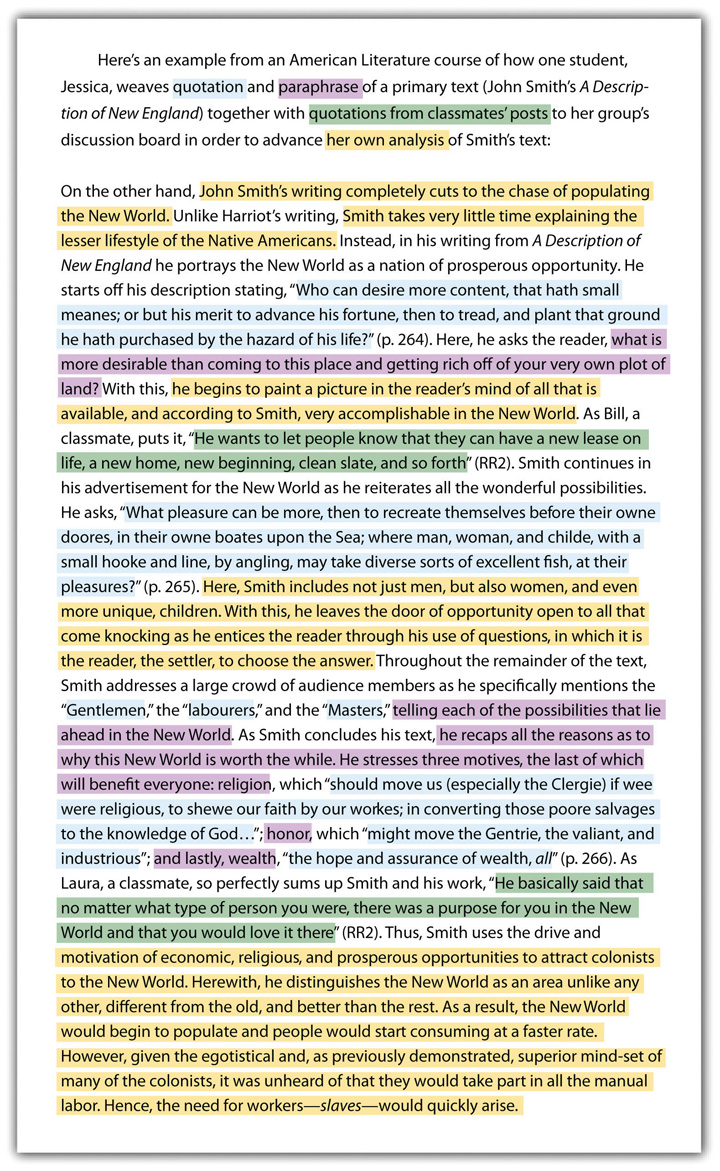

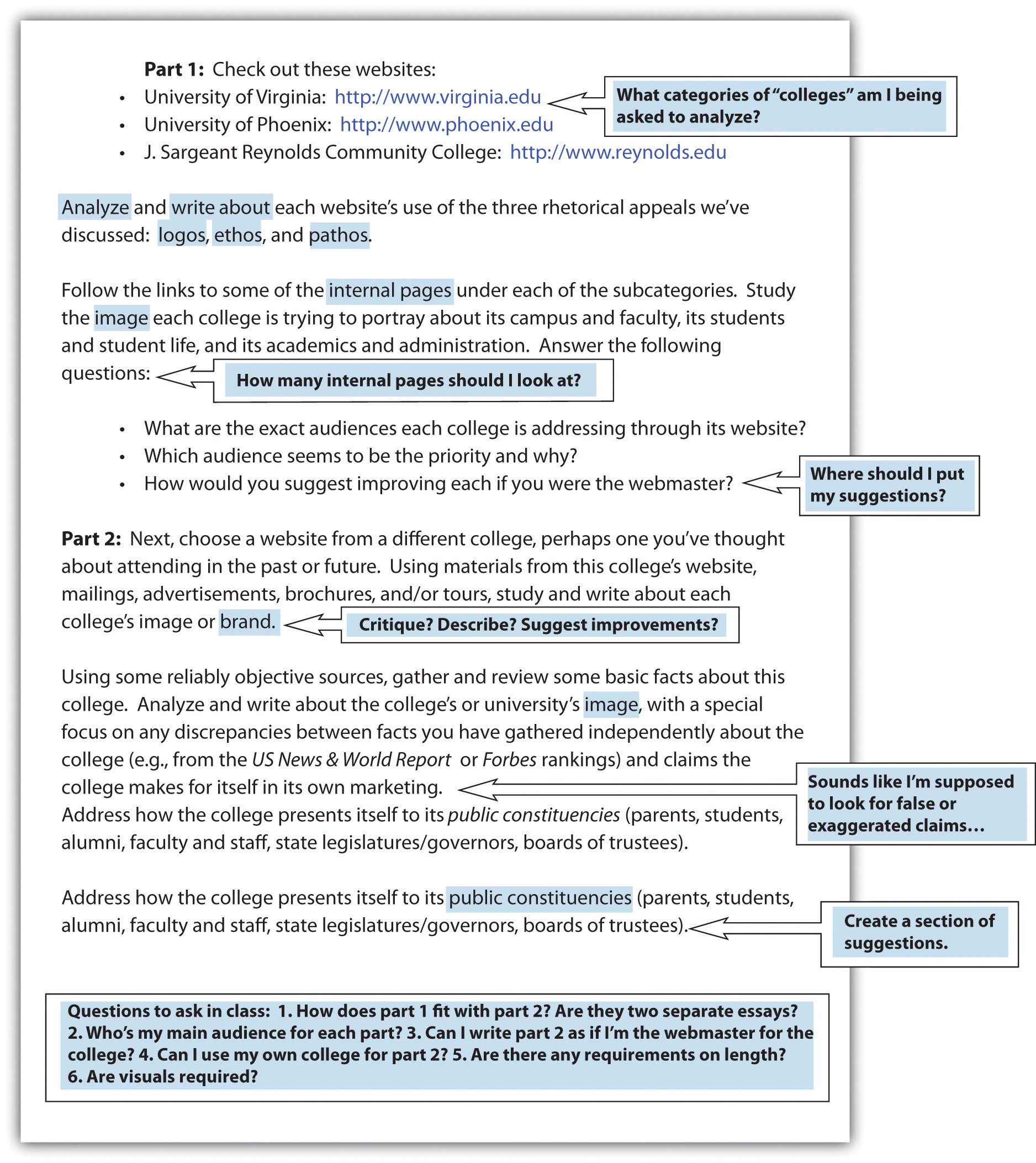

Figure 11.1 Sample Assignment with Student Annotations

11.3 Collaborating on Academic Writing Projects

Learning Objectives

- Understand how cooperative and collaborative learning techniques, with the help of technology, can enhance college-level writing projects.

- Learn how to give and receive effective and meaningful feedback.

How do you feel about group projects in your college classes? Are you like many students who resist group projects because you prefer to work alone? Do you know why college-level work often requires collaboration and how that collaborative work might be conducted differently than how it’s done in a K–12 environment?

Different Types of Group Work

You might not think of a typical writing assignment as a group project, but you begin collaborating on a writing assignment the moment you discuss your topic with someone else. From there, you might ask classmates to read your paper and share their opinions or to proofread your work. Some students form study groups to assure they have reviewers for their work and to have a collaborative atmosphere in which to work. These are just a few examples of effective college students voluntarily engaging in collaboration.

Choosing to collaborate is not always left up to you, since some instructors often require it, whether through simple group discussion boardsA feature of course management systems that allows students to post entries in response to discussion questions. or through more complex interactions, such as a semester-long project. Whether or not it starts out as something that’s required, or “part of your grade” for the course, collaboration is something successful college students eventually learn to do on their own.

If your instructor gives you a collaborative writing assignment, don’t assume the worst possible outcome, where one or two people end up doing all the work. Decide and document who will do what and when it will happen. As a group, you are taking on nearly total responsibility for the project when you are involved in a collaborative learningAn educational method that requires groups of students to take nearly complete responsibility for organizing and scheduling their work together. situation. Because of their complexity, collaborative writing projects still tend to be fairly uncommon, but they are becoming increasingly popular ways of developing and testing your collective ability to think, work, and communicate interdependently as part of a team—certainly an essential skill in the workplace.

The Dynamics of Interpersonal Communication

If collaboration is required, making a plan at the beginning of the assignment is essential. Decide if you will meet in person, online, or both. If the level of collaboration is at the reviewing and proofreading level, agree on a date to turn in or post drafts for review and set a clear timeline for completing reviews. For more involved collaborative efforts, such as a joint paper or project, begin by agreeing on a vision for the overall project. Then set up a schedule and split up the work evenly and equally, but with a sense of strategy as well. Figure out each other’s strengths and play to them. Make sure the schedule allows for plenty of time to regroup in case a group member does not meet a deadline.

During group meetings, discuss the direction and scope of the overall project as well as individual components. If any group members are struggling with their parts of the project, keep in mind that the success of all depends on the success of each, so meet to address problems. When group members disagree—and there will almost always be some differences of opinion—talk through the problems with a willingness to compromise while being careful to protect the overall integrity of the assignment. Choose an individual deadline for completion that allows time for all group members to read through the draft and suggest further revisions. If your project includes a presentation, make sure to leave time to plan that as well. Decide if one or more people will present and schedule at least one practice session to assure the group members are happy with the final presentation.

General Group Work Guidelines

- Make sure the overall plan is clear. A group project will only come together if all group members are working toward the same end product. Before beginning to write, make sure the complete plans are fleshed out and posted in writing on the group website, if one is available. Within the plan, include each member’s responsibilities.

- Keep an open mind. You will undoubtedly have your ideas, but listen to other ideas and be willing to accept them if they make sense. Be flexible. Don’t insist on doing everything your way. Be tolerant. Hold back from criticizing others’ errors in an insulting way. Feel free to suggest alternatives, but always be polite. If you think someone is criticizing you unfairly or too harshly, let it go. Retaliating can create an ongoing problem that gets in the way of the project’s completion.

- Be diplomatic. Even if you think a coparticipant has a lousy idea and you are sure you have a better idea, you need to broach the topic very diplomatically. Keep in mind that if you want your opinion to have a fair hearing, you’ll need to present it in a way that is nonoffensive.

- Pay attention. Make sure you know what others are saying. Ask for clarification when needed. If you are unsure what someone means, restate it in your words and ask if your understanding is correct.

- Be timely. Don’t make your coparticipants wait for you. As a group, agree to your timing in writing and then do your part to honor the timeline. Allow each person ample time to complete his or her part. Tight schedules often result in missed deadlines.

Managing Consistency of Tone and Effort in Group Projects

Human nature seems to naturally repel suggestions of change from others. It is wise to remember, however, that no one is a perfect writer. So it is in your best interest to welcome and at least consider others’ ideas without being defensive. Guard against taking feedback personally by keeping in mind that the feedback is about the words in your paper, not about you. Also show appreciation for the time your classmate took to review your paper. If you do not completely understand a suggestion from a classmate, keep in mind the “two heads are better than one” concept and take the time to follow up and clarify. In keeping with the reality that it is your paper, in the end, make only the changes with which you agree.

When you review the work of others, keep the spirit of the following “twenty questions” in mind. Note that this is not a simple checklist; the questions are phrased to prevent “yes” or “no” answers. By working through these questions, you will develop a very good understanding about ways to make the writer’s draft better. You’ll probably also come up with some insights about your draft in the process. In fact, you’re welcome to subject your draft to the same review process.

When you have an idea that you think will help the writer, either explain your idea in a comment box or actually change the text to show what you mean. Of course, only change the text if you are using a format that will allow the author to have copies of both his or her original text and your changed version. If you are working with a hard copy, make your notes in the margins. Make sure to explain your ideas clearly and specifically, so they will be most helpful. Do not, for example, note only that a sentence is in the wrong place. Indicate where you think the sentence should be. If a question comes into your mind while you are reading the paper, include the question in the margin.

Twenty Questions for Peer Review

- What sort of audience is this writer trying to reach? Is that audience appropriate?

- What three adjectives would you use to describe the writer’s personality in the draft?

- How well does the draft respond to the assignment?

- What is the draft’s purpose (to persuade? to inform? to entertain? something else?) and how well does it accomplish that purpose?

- Where is the writer’s thesis? If the thesis is explicit, quote it; if it is implicit, paraphrase it.

- What points are presented to support the thesis?

- How do these points add value in helping to support the thesis?

- How does the title convey the core idea in an interesting way?

- How does the paper begin with a hook that grabs your attention? Suggest a different approach.

- How effectively does the writer use visuals? How do they add value?

- Where else could visuals be used effectively? Suggest specific visuals, if possible.

- How are transitions used to help the flow of the writing? Cite the most effective and least effective transitions in the draft.

- Is the draft free of errors in punctuation and grammar? If not, suggest three changes. If there are more than three errors, suggest where in this handbook the writer could find assistance.

- How varied are the sentence styles and lengths? Give one example each of a short, simple sentence and a long, complex sentence in the draft.

- What point of view is used throughout the paper?

- How well does the conclusion wrap up the thesis? What else could the conclusion accomplish?

- How are subheadings used, if they are used?

- What are the strongest points of the draft?

- What are the weakest points of the draft?

- What else, if anything, is confusing?

Assessing the Quality of Group Projects

Instructors assess group projects differently than individual projects. Logically, instructors attribute an individual assignment’s merits, or lack thereof, completely to the individual. It is not as easy to assess students fairly on what they contributed individually to the merits of a group project, though wikis and course management systemsA web-based learning environment that organizes the work of a course (e.g., Blackboard). are making individual work much easier to trace. Instructors may choose to hold the members of a team accountable for an acceptable overall project. Beyond that, instructors may rely on team members’ input about their group for additional assessment information.

For an in-depth collaborative project, your instructor is likely to ask all students in the group to evaluate their own performance, both as individuals and as part of the larger group. You might be asked to evaluate each individual group member’s contributions as well as the overall group efforts. This evaluation is an opportunity to point out the strong and weak points of your group, not a time to discuss petty disagreements or complain about group plans that did not go your way. Think about how you would feel if group members complained about your choices they did not like, and you can easily see the importance of being flexible, honest, and professional with group evaluations. For a clear understanding of how an instructor will grade a specific collaborative assignment, talk to the instructor.

Key Takeaways

- Online tools and platforms like course management systems and wikis allow students to collaborate by sharing information and by editing, revising, and publishing their finished work.

- Collaborative learning approaches are increasingly prevalent in higher education, as colleges attempt to prepare students for the demands of increasingly collaborative work environments.

Exercises

- If the writing course in which you are currently enrolled is not using a wiki, write a rationale to your instructor for how the course might benefit from having such a collaborative platform. (Check out two of the most popular wikis for which free educational versions are currently available: http://www.wikispaces.com and http://www.pbworks.com.) Include an evaluative comparison in your proposal and suggest to your class and instructor which would be the best to use for your writing course and why. Make sure you take into account how you would observe the syllabus and assignments currently in place for your course, and consider how they might be adjusted to meet the demands of a more collaborative context.

- As part of your proposal, you could set up a free wiki online and create a one-page essay explaining the process of setting up a free wiki. Publish your essay in your wiki and then give the rest of the class and your instructor permission to see your essay. If your writing course is already using a wiki, consider how you would draw up a similar proposal to an instructor in another discipline. For example, how would a history, biology, psychology, business, or nursing course benefit from a wiki?

- Choose an essay you have written for a previous assignment in class. Exchange the paper with a classmate. If possible, exchange an electronic version rather than a hard copy. Answer each of the “Twenty Questions for Peer Review” in this section. When necessary, make notes in the margins of the paper (by using Insert Comment if you are working in Word, then resaving the draft before returning it electronically).