This is “Publishing”, chapter 10 from the book Writers' Handbook (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 10 Publishing

The Final Step

Every time you share a final version of your work, even if it’s only with your instructor and classmates, you are publishing it. The last step in writing an essay is deciding how to publish your work. You might be given specific directions from your instructor; you might take your directions from specific style guides, such as the American Psychological Association (APA) or Modern Language Association (MLA); or you might be free to make your choices about document design. Whichever category your project falls into, the first section in this chapter will give you some helpful ideas. The remaining two sections will present some tips for digital presentations and for presenting orally.

10.1 Choosing a Document Design

Learning Objectives

- Be aware of general format choices.

- Know basic American Psychological Association (APA) format choices.

- Know basic Modern Language Association (MLA) format choices.

Chapter 9 "Designing" explores general and specific aspects of designing your written work, including margins, line spacing, indentation, alignment, headings, subheadings, fonts, visual text, images, charts, graphs, and text wrapping. In this section, you will learn about the document design requirements of two of the most common style sheets: those from the American Psychological Association (APA) and the Modern Language Association (MLA). (For more on citation and documentation formats from these and other style sheets, see Chapter 22 "Appendix B: A Guide to Research and Documentation".)

Following APA Document Design Guidelines

Order of Pages

APA requires the following set order of pages with each listed page on the list starting on a new page. If your paper does not require one or more of the pages, skip over those pages, but maintain the order of the pages you do use.

- Title page

- Abstract

- Body

- Text citations

- Footnotes (If used, these may be placed at bottom of individual pages or placed on a separate page following the citations.)

- Tables too large to place within the text body can be included in this position

- Figures too large to place within the text body can be included in this position

- Appendices

Title Page

A double-spaced title page should include the required information centered on the top half of the page. The title page information can vary based on your instructor’s requests, but standard APA guidelines include either the title, your name, and your college name or the title, your name, the instructor’s name, the course name, and the date.

Page Numbers and Paper Identification

Figure 10.1

Page numbers should be placed at the top, right margin one-half inch down from the top of the page. Across from the page number, flush left, include the title of the paper in a running head. If the title of the paper is lengthy, use an abbreviated version in the running head.

Margins

Make margins one inch on both sides and top and bottom.

Headings and Subheadings

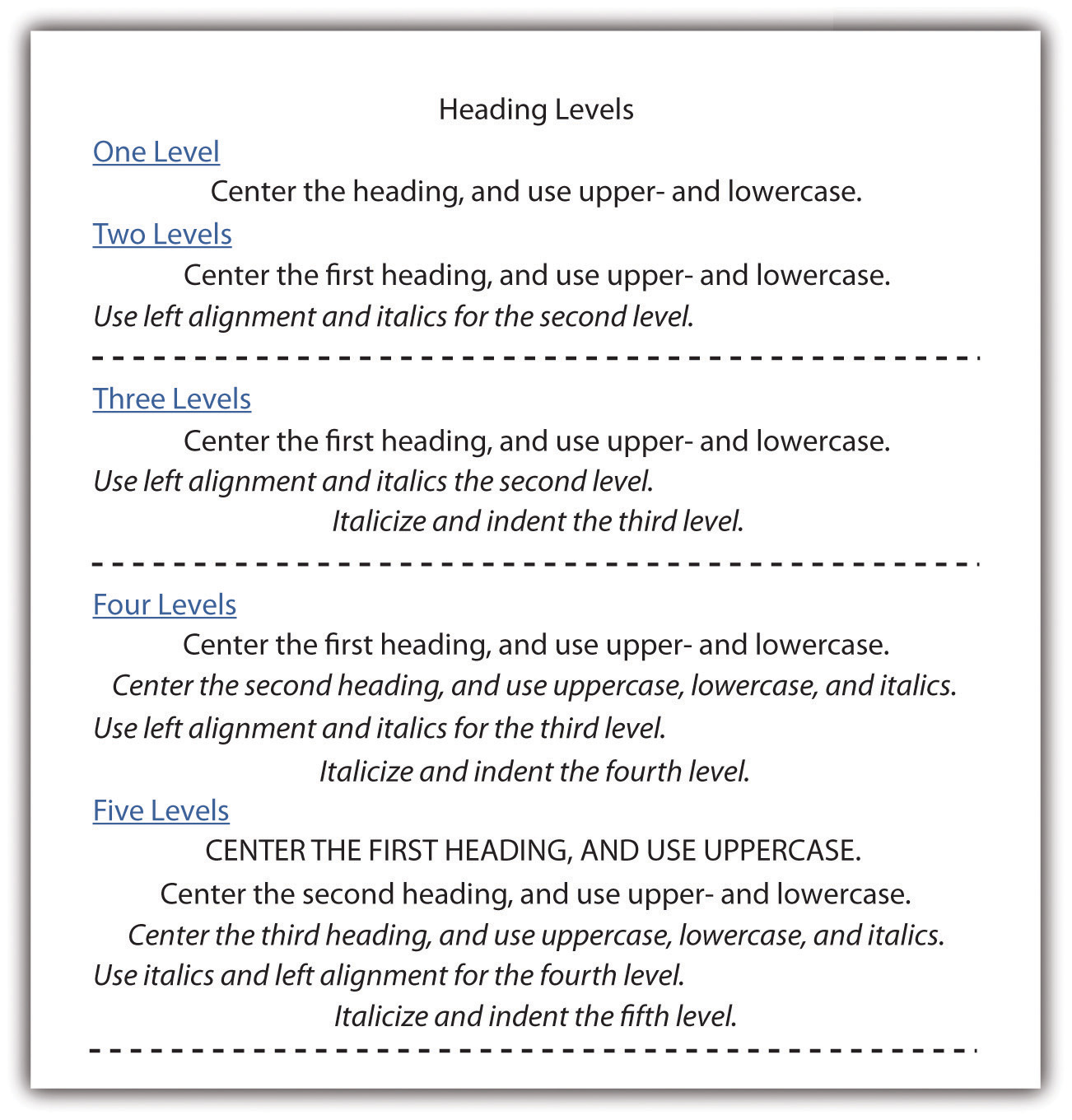

Use double spacing with no additional returns. Before you decide where to place your headings, you have to decide how many levels of headings you will have. Typically, you will have two or three levels, but you might have as many as five levels. Keep in mind that the title does not count as a heading level, you should use the levels consistently, and you must have a minimum of two headings at each level. See Figure 10.2 for examples of formatting for different numbers of headings levels.

Figure 10.2

Fonts

Use 12-point Times New Roman.

Paragraph Indentations

Indent the first word of each paragraph from five to seven spaces.

Line Spacing

Double-space all text, including titles, subheadings, tables, captions, and citation lists.

Spacing after Punctuation

Space once after punctuation within a sentence, such as commas, colon, and semicolons, and twice after end punctuation.

Following MLA Document Design Guidelines

Order of Pages

MLA requires the following set order of pages with each listed page on the list starting on a new page. If your paper does not require one or more of the pages, skip over those pages, but maintain the order of the pages you do use.

- Body of text

- Notes

- Citation list

- Appendices

Title Page

No title page is needed unless your instructor requests it. Instead of a title page, MLA requires that you double-space your name, instructor’s name, course name or number, and the date at the top left. Next, continuing to double space, center the title on the page and start your text under the title.

Page Numbers and Paper Identification

Figure 10.3

Page numbers should be placed at the top, right margin one-half inch down from the top of the page. Before the page number, use your last name in a running head.

Margins

Make margins one inch on both sides and top and bottom.

Headings and Subheadings

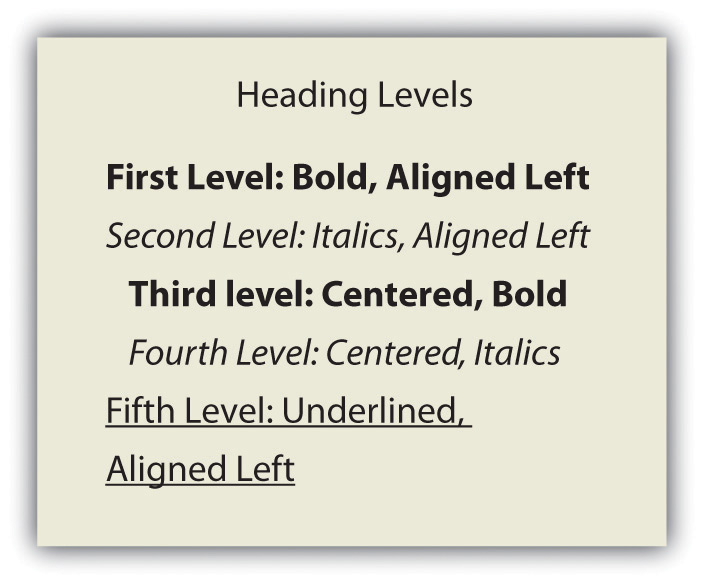

Use double spacing with no additional returns. Use the heading formats in Figure 10.4 for up to five headings. If you have only two headings, use only the first two formats and so on.

Typically, you will have two or three levels, but you might have as many as five levels. Keep in mind that the title does not count as a heading level, you should use the levels consistently, and you must have a minimum of two headings at each level.

Figure 10.4

Fonts

Choose a font that is straight forward with no curly flairs or other “fancy” twists, such as Times New Roman or Arial. Use 12-point font.

Paragraph Indentations

Indent the first line of each paragraph one-half inch from the left margin by using the tab key (rather than spacing over).

Line Spacing

Double-space all text, including titles, subheadings, tables, captions, and citation lists.

Spacing after Punctuation

Leave only one space after all punctuation (both inside and at the end of sentences).

Key Takeaways

- In absence of set design requirements, make design choices that result in ample white space, value-adding images, a variety of images, consistent headings that help organize the content for the reader, contrast used to identify important aspects, detailed information being presented in appendices, and a clean overall look. (See Chapter 9 "Designing" for general guidelines.)

- Along with many other details on citation and documentation covered in Chapter 22 "Appendix B: A Guide to Research and Documentation", APA style sheet guidelines include a set order of pages, requirements for a title page, page number and page identification format, margin widths, heading formats, font choice and size, paragraph indenting, line spacing, and spacing after punctuation.

- MLA style sheet guidelines include specifics in the same categories as do the APA guidelines, with the exception of a title page since MLA does not require one.

Exercises

Read each guideline and identify it as a general guideline, an APA guideline, or an MLA guideline.

- Use ample white space.

- When using five levels of headings, the first level should be in uppercase.

- The first page should be the title page.

- The author’s last name is placed in the running head with the page number.

- Make sure your paper has a clean look.

- Indent the first sentence in a paragraph a distance of one-half inch.

- The paper title should be included in the header with the page number.

- Insert two spaces after every sentence.

- The fifth heading level should be aligned left and underlined.

10.2 Developing Digital Presentations

Learning Objectives

- Recognize that PowerPoint slides are useful for creating digital presentations.

- Know that you can develop digital presentations in class wikis, in Word files that are submitted through e-mail, in course management systems, in personal websites, and on films posted on the Internet or burned to a DVD.

- Understand how links, video segments, and audio pieces are used in digital presentations.

As technology advances, the options for digital presentationsDelivery of information that exists only in the virtual world without using paper. continue to grow. Digital presentations refer to methods of presenting your work in the virtual world without using paper. Some of the most common current options are included in this section. All the options can take advantage of links to other parts of the document as well as links to related locations on the Internet. Using such links is one way to take advantage of the capabilities available in digital work. The internal linksA hyperlink within a document that leads to other locations within the document. allow readers to instantly access other sections of your paper. External linksA hyperlink within a document that leads to locations outside of the document. lead to related text, videos, or audio pieces that are located on the Internet. Most of these digital options also allow you to embed video or audio segments so that the reader can simply click on a button or arrow to activate the segments. (For more on what’s at stake when you write for and publish on the web, also see Chapter 13 "Writing on and for the Web".)

Creating PowerPoint Slides

PowerPoint is Microsoft Office software that has nearly become a standard presentation software. When you create PowerPoint slides to present your paper, you should use a small number of slides, typically less than ten. The slides should cover the most important aspects of your paper and should be at least somewhat visual in nature. PowerPoint also presents the option of textual and visual animation as well as audio components. In an effort to keep your slides as visual as possible, place bullets next to sentences whenever possible. Also, use fonts that are large enough for a group to read from a screen: 28 points or larger for base text and at least 36 points for headings.

Allow for ample white space on each slide. Without making the pages overwhelming, use color and visuals to add interest to the slides. If you do not have value-adding images, tables, or graphs that you can use, you can add color to the background, to text, or to text boxes.

You can add your voice and other audio to your slides. And you can create a slideshow that you can turn on and run automatically, presenting visuals and sound simultaneously. These capabilities allow you to create your entire presentation and run it without actually saying a word during the presentation. If you intend to run an automatic presentation, make sure you go through practice runs until the entire presentation works as you intend it to work.

Submitting Files Electronically

Chances are, you will create your paper using Microsoft Word, which has nearly evolved into the standard word processing software in higher education. If you’re not working in Word, save your file as a Word document or in a Word-like format your instructor and peers are likely to be able to open. You will likely be asked to submit your major essays digitally as e-mail attachments or through a digital dropboxA portal for uploading documents within a course management system., file exchangeAnother feature of course management systems allowing students to submit their work., or assignment area within the course management system your instructor or college is using, such as Blackboard. If you are asked to submit your essays digitally, you should assume your instructor and peers will be reading your work on a computer screen and quite possibly online. Therefore, your work can include links and imbedded audio and video components. If, on the other hand, you are asked to submit your essays in hard copy, you can’t make the same assumptions about how it is likely to be read and assessed. There’s nothing wrong with asking for permission to submit your work digitally if you prefer for it to be assessed in that context.

Posting on a Personal Website

You could present your work on your personal website using web features, such as homepages, navigation buttons, links to other sites, buttons that activate audio and video segments, and overall visual presentations. As a college student, you should only present your work this way when instructed to do so by your instructor. Since not all students have a personal website, this option is still not widely used as a means of presenting college work; however, some instructors are moving in this direction, especially as digital portfolios become an increasingly common expectation. (For more on digital portfolios, see Chapter 13 "Writing on and for the Web", Section 13.4 "Creating an E-portfolio".)

Working on a Class-Wide Wiki

Your instructor might have an online class site where you and your classmates can post your papers, review each other’s work, and edit your work. When the due date arrives, your instructor would then read your final version. In this case, your entire paper would function as a digital presentation. Your instructor can read through your paper, follow your links, and listen or watch video and audio segments you have included. Keep in mind that, unlike a course management system requiring a password and enrollment in the course, both personal websites and class-wide wikis may well be visible to anyone using the web. This fact should cause you some concern about the content you share and the way you choose to present yourself and your identity, but it can also provide a meaningful opportunity to write for external, real audiences.

Filming a Digital Presentation

Using video filming equipment, you could film yourself presenting your work and capture both audio and video. You could then upload your presentation to the Internet (via a common video sharing site like YouTube) or you could burn it to a DVD. If you want your digital films to include a variety of multimedia options, you would have to learn how to incorporate such features using the equipment available to you.

Key Takeaways

- When using a PowerPoint slide to present your paper, you should use less than ten slides to cover the important aspects of your paper. PowerPoint presentations can include textual and visual animation as well as voice and other audio. PowerPoint gives you the opportunity to create an entire presentation and run it as a slideshow without you saying a word.

- When you present your work digitally, you typically have the option of linking one part of your work to another or linking your work to relevant locations on the Internet. Within digital presentations, you can also often embed video and audio pieces.

- You can digitally share your work by submitting Word files as e-mail attachments; using a digital dropbox, file exchange, or assignment features on course management systems; posting files on your personal website; using class wikis; or filming your presentation and then posting it on the Internet or burning it to a DVD.

Exercises

- Create two PowerPoint slides that contain the same basic information. Make one slide that uses the visual preparation suggestions in Section 10.2.1 "Creating PowerPoint Slides" and one that does not use those suggestions. Ask your classmates to identify the good and bad points about your two slides.

- Create a PowerPoint slide that includes both audio and visual components. Demonstrate your slide’s functions for your classmates.

- Write a two-page Word essay and include an internal link from the first page to a point on the second page and an external link to an Internet site. Demonstrate your links for your classmates and explain why the links are meaningful.

10.3 Presenting Orally

Learning Objectives

- Be aware of the different choices you should make for an oral-only presentation; an oral, camera-image presentation; or an oral, in-person presentation.

- Understand how to effectively use a PowerPoint as a presentation tool.

- Know how to prepare for and give a presentation

In public speaking, keep in mind that you are trying to achieve the golden middle ground between impromptuA type of public speaking that does not require advance preparation and thus can be unpredictable and less than professional. (off-the-cuff) speaking that can lead to a chaotic and unorganized mess versus completely robotic reading from a large body of text, which will put your audience to sleep. That middle ground is called extemporaneousA kind of public speaking technique that works from a set of notes or PowerPoint slides but does not simply read those notes or slides verbatim. speaking, based on the technique of speaking from notes.

You can present orally in person or online. If you present orally online, you can do so with just sound or with the use of a camera that allows your listeners to see you. Many laptops include built-in cameras and microphones that make it surprisingly easy for you to create a social, visual presence.

Whether you are presenting in person or online, you need to set yourself up to present without having to remember everything you want to say. One way to create prompters that you can use very smoothly is to use PowerPoint slides that you can show as you talk and that can prompt your memory about what you want to say. When you use a PowerPoint in this way, you only see information your audience is looking at so you never have a problem with trying to look at your notes too much. One grave pitfall to this method is the tendency to read from the PowerPoint slides, which can be very boring for your audience, who also presumably can read. A good oral presentation from PowerPoint should be just as extemporaneous as one delivered from note cards.

If using a PowerPoint is not an option, you can present orally using note cards. When using cards, number them to assure they are in the proper order. Since you don’t want to read your cards, don’t write out your entire speech on the cards. Instead use only cues and place one idea per card so that you can turn to the next card as you transition to the next idea. On your note cards, use text that is large enough for you to easily read at a glance. On the back of the card, add additional details in a smaller font in case you must check out information beyond the basic cue.

When you use a PowerPoint, you can have built-in visuals, but when you use cards, you need to consider adding visuals in the form of items, posters, images on a computer screen (local file or one found on the Internet), handouts, and so on. Display visuals or pass out handouts when you want your audience to look at them, otherwise they are likely to be checking out your visuals when you want them to be listening to you.

Keep your audience members in mind when you plan your presentation. Based on their knowledge of your topic, interest in your topic, and attitudes about your topic, decide how basic, how long, and how in-depth your presentation will be.

The amount of preparation you put into the speech in advance will make all the difference. Allow ample time to practice your oral presentation several times. If you are presenting in person or with a computer camera, you might want to record it or practice it in front of a mirror so you can visually see how your presentation comes across and can make desired adjustments. If you have a tendency to talk quickly all the time or when you are nervous, practice talking at a slower pace so your audience will have an easier time following you. Make sure you can consistently talk loudly enough for the whole audience to hear you. If your voice isn’t loud enough, consider using a microphone since an audience that cannot hear quickly becomes unhappy.

While you are practicing, keep track of the amount of time your presentation takes so you can lengthen it or shorten it as needed to meet requirements. If feasible, stand while you present so you will make the strongest possible impression. If you are presenting in person, face your audience and make eye contact with your audience members.

Plan to open your presentation with an attention-grabbing comment, visual, activity, joke, story, or situation. If you capture your audience’s attention at the very beginning, you have a chance of keeping it throughout your presentation. On the other hand, if you lose the audience’s attention at the beginning, it will be very difficult to regain it.

Keep in mind that you do not have to share every detail of your essay in an oral presentation based on it. Choose a few highlights and focus on them in an effort to give a general idea about your work. Speak directly and personally to your audience, using first-person and second-person pronouns like “I,” “you,” and “we.” Use simple sentences that are easy to follow and include visuals of unfamiliar terms. Stay in tune with your audience so you know when they are keenly interested and would appreciate additional elaboration as well as when they are losing interest, which signals that it would be wise to move onto the next topic.

Conclude your presentation by referring back to the interest-grabbing opener or offering another appropriate anecdote or memorable quotation, phrase, comment, or image. When you finish presenting, ask your audience members if they have any questions. If possible, allow as much time as needed to address all questions. Then thank your audience for their attention to your presentation.

If you are nervous about your presentation, keep in mind that nervousness is normal and that it can help bring energy to your presentation. And implement the following ideas to help you remain calm and in control:

- Know your material thoroughly so you can easily immerse yourself in talking about it. Then remind yourself that you know the materials and will easily be able to share what you know.

- Write out your opening sentence or two so you get started on track even if you plan to speak extemporaneously for the balance of the speech.

- Stay with your plan. If you nervously start talking aimlessly, you can easily find yourself beginning with points that belong in different parts of your presentation and have a difficult time getting back on track to present your information in the intended order.

- Get all ready and then sit down and relax. Do not start immediately following a frenzied setup period.

When you are presenting online, keep the following tips in mind:

- Practice so that your timing is smooth, you know for sure how to use the technology, and your presentation appears polished. If you are using a PowerPoint, make sure each point matches up with the PowerPoint slide that is showing.

- Do not read PowerPoint slides. Your audience can read for themselves. Use your slides to enhance what you are saying.

- Make sure that you have everything you need right by your computer so that you do not have to leave the computer (or the camera) at any time. You can write a script for each slide and read the script while also adding related commentary as it makes sense.

- Keep in mind that your audience cannot benefit from any of your facial expressions or body movements if they cannot see you. And even if you are using a camera, they might not be able to see you clearly enough to get information sent through expressions or movements. So be very careful to use words vividly to convey your complete message.

- Talk slowly and enunciate clearly to give your audience the best possible chance of understanding you. People often have trouble understanding speech over the Internet.

- Make sure your audience members know how to get your attention during the presentation if you are planning to allow them to ask questions.

- Look directly at the camera to give the effect of eye contact with your audience members in video presentations.

- Keep in mind that everything you say and every noise you make, such as the screech of a scooting chair, can be heard or seen by the audience. Also, if you have a camera, remember that every facial expression and other things you do can possibly be seen.

- Be relaxed and professional, and most of all, be yourself. You’re not filming a major motion picture or putting on a Broadway show. Think about the kind of voice and image you would want to listen to online or in person.

Key Takeaways

- You can present orally in person, online with visuals, and online without visuals.

- A PowerPoint can be an asset to a presentation both as an avenue for presenting visuals and as a method of having presentation cues available as you speak.

- When preparing for a presentation, keep your audience in mind, allow time to practice, and plan for an interesting introduction and conclusion.

- When presenting online, make sure you know how to use the technology, use a PowerPoint, take extra care to enunciate clearly, and keep in mind that your audience members can see and hear everything you do and say even though you can’t see them.

Exercises

-

Use the information in this section to complete each of these statements.

- A PowerPoint can be an asset to both online and in-person presentations because…

- If you are using note cards, you should put one idea on each card because…

- During your presentation, you should move onto a new topic sooner than planned if you notice your audience…

- You should practice both in-person and online presentations several times because…

- If you are nervous, make sure to stay with your plan because…

- You should take extra care to enunciate clearly when you are presenting online because…

- Watch an hour or so of C-SPAN whether live on television or by going to the massive archive of public speeches on http://www.c-span.org. Compare at least three speakers and determine which one is most effective at finding the “golden middle ground” of speaking extemporaneously.