This is “The Reagan and Bush Years, 1980–1992”, chapter 13 from the book United States History, Volume 2 (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 13 The Reagan and Bush Years, 1980–1992

By the summer of 1980, most Americans were deeply concerned about the economy and world events. Stagflation had taken its toll on the economy and unemployment approached 8 percent. Interest rates remained so high that few businesses or consumers could take out loans. The energy crisis continued to remind Americans of their nation’s vulnerabilities. Even worse, America seemed helpless in the face of Iranian terrorists who still held fifty-two American hostages. Americans were also concerned that annual budget deficits continued even after the Vietnam War ended. As the 1980 elections arrived, only a third of Americans approved of the job President Jimmy Carter was doing. Only Nixon, at the height of the Watergate scandal, had lower approval ratings.

In response to all of these factors, many Americans supported a growing conservative movement that promised a new direction for the nation based on limiting the size and power of the federal government. Other conservatives lashed out at liberal programs they believed had failed and recipients of welfare, recent immigrants, and supporters of affirmative action. Former actor turned politician Ronald ReaganA leading Hollywood actor for several decades, Ronald Reagan entered politics after a rousing speech endorsing conservative presidential candidate Barry Goldwater in 1964. Two years later, Reagan became the governor of California. Reagan nearly defeated Ford in the Republican primary of 1976 and would win a landslide election in 1980 to become the fortieth president. spoke to the concerns of both groups of American conservatives—those who supported the ideas of conservative political and economic theorists and those who believed that America’s problems were the result of a parasitical infection on the body politic. Reagan also appealed to the nostalgia of older Americans who longed for the years when US military’s might was unchallenged and when US factories produced nearly half of the world’s manufactured goods.

Reagan confidently and warmly projected the simple message that he would ensure that American economic power and prestige was restored. Reagan’s campaign was upbeat, simple, direct, and for many of his supporters, uplifting. Reagan’s fetes also reminded many Americans of an earlier time they hoped to return to. Reagan rallies were as full of patriotic optimism as a Fourth of July parade, while Carter’s speeches often felt more like lectures about the problems the nation faced. The message resounded with older whites, especially among white males who were twice as likely to vote for Reagan as nonwhites. For many Americans, however, the way Reagan spoke with and about minorities and the Reagan campaign’s cavalier attitude toward their perspectives threatened to reverse the progress the country had made.

13.1 Conservatism and the “Reagan Revolution”

Learning Objectives

- Understand the goals of the New Right and the way this movement represented the concerns of many Americans of different backgrounds during the 1980s. Also, demonstrate understanding of the perspectives of those who opposed the New Right.

- Explain the priorities of Reagan’s administration and how his economic policies affected the nation. Describe “Reaganomics” both from the perspective of the president’s supporters and his critics.

- Describe the impact women had on the conservative movement. Also, summarize the election of 1980. Explain the key issues of the election and the significance of Reagan’s victory on US history.

The New Right

Many conservatives felt that their perspectives had been marginalized during the 1960s and 1970s. Conservative politicians believed that the shortcomings of liberalism had made many Americans eager for a different approach. These conservative politicians and voters were part of the New RightA coalition of fiscal and social conservatives who supported lower taxes and smaller government while espousing evangelical Christianity. The New Right rose to prominence in the late 1970s and early 1980s and supported political leaders such as Ronald Reagan. of the 1980s, a group that perceived their nation had been derailed by a liberal agenda in recent years. Conservatives hoped to reduce the size of the federal government beyond the military, decrease taxes and spending on social welfare programs, and find a way to repair the nation’s economic strength and global prestige. Most conservatives supported the end of segregation and hoped to end discrimination in employment. However, they disagreed with many of the strategies used to achieve these goals and hoped to reverse programs designed to achieve racial balance through affirmative action.

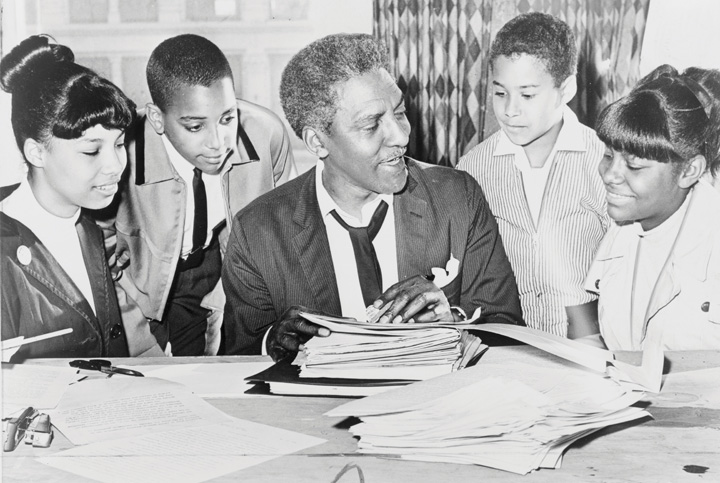

Figure 13.1

Ronald Reagan shakes hands with President Gerald Ford at the 1976 Republican National Convention. Reagan had just been narrowly defeated by Ford in the Republican primaries, but Reagan’s strong showing against the incumbent president demonstrated the former actor’s political appeal to a growing conservative movement.

Just as the New Left sought to distance themselves from the Socialists of the “old left,” the New Right attempted to shed its association with the “old right” that had attempted to keep women and minorities “in their place” during previous decades. The New Right hoped to mix compassion and conservatism, assisting the poor but avoiding the direct welfare payments they believed discouraged individual accountability by rewarding those who did not work. They also hoped to replace the nation’s progressive tax code that charged wealthier Americans higher rates with a new tax bracket they believed was more balanced. By this perspective, Americans who had demonstrated initiative and entrepreneurial skill should be permitted to keep more of their income as a means of encouraging reinvestment.

The conservatives of the 1980s had learned from the social movements of the 1960s, especially the importance of simple and direct messages appealed to Americans’ sense of justice. However, while liberals had looked toward the future in crafting their message, conservatives looked toward the past. This orientation helped the New Right win many supporters during an era of uncertainty about the future. It also offered tremendous appeal to those who feared that traditional values were slipping away. At the same time, the nostalgic orientation of many conservatives encouraged the creation of a sanitized version of the past that neglected America’s many failures both at home and abroad. Perhaps unintentionally, the New Right appealed to many of the same people who had opposed the expansion of civil rights. As a result, there remained a tension between those of the New Right that sought both equality and limited government and those who simply wanted to roll back the clock to another era.

What the base of the conservative movement lacked in racial diversity, it sought to make up by representing a number of different backgrounds and perspectives. Evangelical Christians, struggling blue-collar workers, middle-class voters, and disenchanted Democrats united with economic conservatives and business leaders. Together these individuals supported a movement that merged conservative and probusiness economic policies with socially conservative goals such as ending abortion, welfare, and affirmative action. Interest groups affiliated with the Republican Party also stressed a return to moral standards they identified as “family values.” These conservative groups increasingly viewed opposition to multiculturalism, gay rights, the feminist movement, abortion, busing, affirmative action, illegal immigration, and welfare as panaceas for the nation’s ills.

This new conservative movement advanced a populist rhetoric that appealed to the working and middle classes in ways not seen in US politics since the turn of the century. Unlike the People’s Party of the 1890s, which focused primarily on economic issues, the public focus of the new conservative coalition was on social issues. The challenge for the New Right was that modern politics required the mobilization of both wealth and the masses, two groups that had traditionally opposed one another. The strength of the conservative movement was its ability to weld probusiness economic policies with support for conservative social issues in a way that attracted a core group of devoted supporters and the backing of wealthy donors.

Without the Evangelical revival of the late 1970s and early 1980s, such a coalition might have never occurred. The United States experienced a period of religious revivalism during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Similar to the Great Awakening of the early eighteenth-century, charismatic religious leaders became national celebrities and attracted legions of loyal followers. The most outspoken of these leaders were a new breed of clergy known as “televangelists” who attracted millions of loyal viewers through religious television programs. Televangelists like Billy Graham, Pat Robertson, and Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker saw their virtual congregations grow as they progressed from old-fashioned revival meetings to radio programs and eventually popular television programs like the 700 Club—each broadcast on several Christian cable networks.

Figure 13.2

Evangelical Christians formed the base of the New Right. Pictured here is a group of fundamentalist Christians in Charleston, West Virginia. Evangelicals made national headlines in 1974 when they protested the use of textbooks they believed contained a liberal agenda to spread ideas such as multiculturalism.

Evangelical Christian denominations experienced a tremendous surge in membership during these years. Southern Baptists become the nation’s largest denomination while the more rigidly structured Christian denominations declined in membership. Christian religions in which membership largely shaped one’s daily life, such as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (known colloquially as the Mormons), Seventh-Day Adventists, and the Assembly of God also experienced tremendous growth and influence.

While many of these churches avoided direct political affiliations, some televangelists and independent clergy saw political action as part of their mission. These and other religious leaders advocated a host of conservative social issues and recommended political candidates to their followers. Most churches avoided explicit support for a particular candidate or political party for a variety of reasons. Churches were exempt from taxes because of the doctrine of separation of church and state. Many believed sponsoring political candidates threatened that separation and would lead to forfeiture of a church’s tax-exempt status. Televangelists like Jerry Falwell challenged that division along with several other leading religious conservatives. Falwell hosted the popular Old Time Gospel Hour and solicited his donors to join his political action committee, known as the “Moral MajorityA political action group consisting of an estimated 4 million evangelical Christians at its peak in the early 1980s. The Moral Majority was led by televangelist Jerry Falwell and supported issues such as legalizing school prayer, teaching creationism rather than evolution, and outlawing abortion..” These and other political groups claimed responsibility for the election of President Ronald Reagan and a host of other conservative Republicans. The boast was likely a stretch in the case of Reagan, especially given the public’s frustration with Carter and the small following these interest groups enjoyed in 1980. However, during the 1982 congressional election, groups such as the Moral Majority enjoyed the support of millions of donors. As a result, the endorsement of these religious-political groups was essential in many congressional districts.

The religious fervor of the 1980s featured aspects of protest against the materialism of the decade, as well as a celebration of it. Just as some Puritans of the colonial era believed that wealth was a sign of God’s favor, wealthy individuals during the 1980s were more likely to flaunt their affluence than previous generations. Displays of conspicuous consumption had become regarded as unsavory during the more liberal era of the 1960s and 1970s, but during the 1980s, they were once again celebrated as evidence that one adhered to righteous values such as hard work and prudence. Many of the leading televangelists joined in the decade’s celebration of material wealth by purchasing lavish homes and luxury items. The result was a number of high-profile investigations into the possible misuse of donations by televangelists.

Many conservatives, especially white Southerners, inherited traditions of suspicion toward the federal government. This circumspection was magnified by the federal government’s legalization of abortion and stricter enforcement of the doctrine of separation of church and state in the public schools. Conservatives also bristled at many of their governmental leaders’ growing toleration of homosexuality while mandatory school prayer and state-funded Christmas celebrations were forbidden. From the perspective of social conservatives, each of these occurrences demonstrated that large and powerful government bureaucracies were more likely to support liberal causes. As a result, Evangelicals increasingly supported both social and fiscally conservative causes. Tax breaks, the elimination of welfare programs, and the reduction in the size of the federal government became leading issues of the new Evangelicals. However, most of the new religious right also supported increasing the power of the government to ban behaviors they believed were sinful, while supporting increased authority for law enforcement and larger budgets for national defense.

A variety of conservative intellectuals who were concerned with each of these social issues had developed a number of organizations dedicated to advancing their ideals among the American people. These “think tanks,” as they would euphemistically be called, included the American Enterprise Institute and the Heritage Foundation, among others. Each of these groups depended on the donations of both rank-and-file conservatives and a number of wealthy donors. As these groups and the conservative causes they believed in grew in popularity, conservative politicians won elections by promoting the issues these think tanks supported. Although many conservative politicians tended to subordinate their economic platform in favor of discussing hot button conservative issues that mobilized their supporters, by 1980, many conservative voters also came to believe that lowering taxes for corporations and the wealthy while reducing government spending for social programs would lead to greater prosperity. In other words, the conservative movement succeeded not only by mobilizing voters on social issues but also by altering the perception of the government’s proper role in the economy. Whereas middle- and working-class Americans had been more apt to support unions and progressive tax policies during the previous three decades, by the 1980s, a growing number of these same individuals agreed with conservatives about the potential danger of powerful labor unions and feared that higher taxes for corporations and the wealthy might discourage economic growth.

Election of 1980

Reagan first tapped into the frustrations of the 1970s as a gubernatorial candidate in California promising to cut taxes and prosecute student protesters. As a presidential candidate in 1980, he took every opportunity to remind Americans of the current recession. The Reagan campaign convinced many voters that Carter had made the problem worse by pursuing strategies that tightened the money supply and pushed interest rates as high as 20 percent. Although inflation was the main reason these rates were so high and Carter’s actions would reduce inflation over time, the inability of corporations and consumers to borrow money in the short term added to the dire condition of the economy in the summer of 1980. “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” Reagan asked, connecting the nation’s economic problems to the Carter administration. The fact that the recession predated Carter’s election mattered little. “A recession is when your neighbor loses a job,” Reagan later remarked as the election neared. “A depression is when you lose yours.” After pausing for effect, the former actor delivered his final line: “and recovery begins when Jimmy Carter loses his.”

Candidate Reagan promised to reverse America’s declining international prestige and restore its industrial production—two problems many agreed had grown worse under Carter’s watch. Reagan also promised to reduce taxes in ways that would spur investment and job creation, reduce the size of the federal government, balance the federal budget, and strengthen national defense. More importantly, he communicated what most Americans believed to be true—that theirs was a strong nation with a noble past. Behind Reagan’s populist appeal was one essential message with a long history in American political thought: freedom from government rather than freedom through government. Reagan preached that the cure for America’s ills was to take decision making and power away from Washington and place it in the hands of US businesses and consumers.

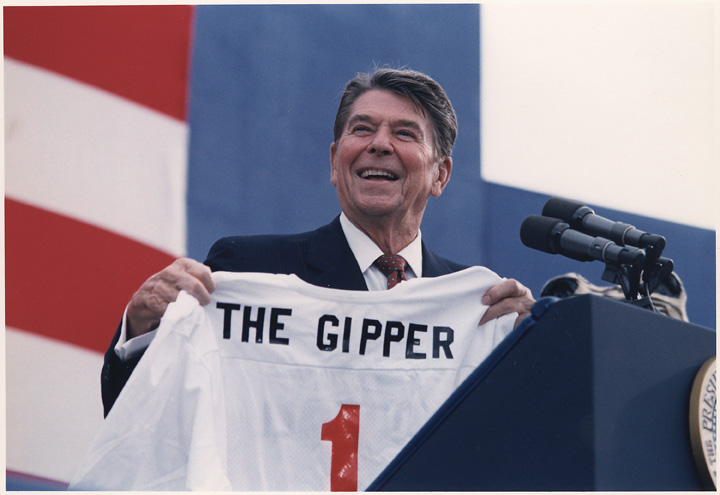

Figure 13.3

As a Hollywood actor, Ronald Reagan played the character of Notre Dame’s George Gipp. In this photo, Reagan is holding a customized jersey bearing the nickname “Gipper” but featuring America’s colors instead of the gold and blue of Notre Dame.

Critics of the California movie star claimed that Reagan’s rhetoric was hollow and clichéd, even if it was uplifting. They likely missed the point: Reagan was appealing to a nation that felt like it needed a win. Years before, Reagan starred in a film where he played the role of legendary Notre Dame athlete George Gipp. As the nation appeared to be up against the wall, the former actor now assumed the role of Notre Dame coach Knute Rockne, asking America to “win one for the Gipper.” Reagan’s use of the phrase was out of context, historically inaccurate, and offered nothing in terms of policy or substance. And it was political magic. If presidential elections were popularity contests, Carter did not stand a chance.

With his charisma, charm, and populist appeal, Reagan won the general election by sweeping forty-four states. The Republican Party won control of the Senate for the first time in several decades. The landslide was not as clear as it might appear, however, as voter turnout was so low that only a quarter of Americans of voting age actually cast ballots for Reagan. As some historians often point out, had voter turnout been the same as previous elections and if those voters had followed historical patterns (such as union members supporting the Democratic candidate), Carter would have actually won in a landslide. At the same time, voter apathy is usually a reflection of how many Americans feel about their government. As a result, the low turnout may have been its own kind of referendum on Carter’s presidency. The most significant factor in the election was the political power of the New Right. More than 20 percent of self-identified Evangelical Christians who had voted for Carter in 1976 indicated that they voted for Reagan in 1980.

Even Reagan’s opponents conceded that the new president was one of the finest public speakers when it came to delivering a scripted oration. Years in front of the camera meant that Reagan instinctively knew where to stand and what camera to look at, much to the chagrin of interns whose job it was to place tape marks and arrows on stages across the country. However, Reagan was often adrift when speaking without a script. He relied heavily on clichés and empty platitudes, and sometimes told stories from popular films as if they were part of history or his own life.

While most of Reagan’s tales were anecdotal in nature and some were simply meant to illustrate a point, Reagan’s casualness with the truth could also be quite damaging. As a candidate, Reagan aroused populist anger against welfare recipients by fabricating a story about a woman in Chicago’s South Side neighborhood. This scam artist reportedly drove a new Cadillac and had received hundreds of thousands of dollars in welfare checks under multiple names. Later investigations demonstrated that Reagan had made up the entire story. Even if Reagan would have offered a retraction, the populist anger against welfare recipients could not be easily reversed. Although the woman was fictional, Reagan played heavily on prejudices against African Americans by describing this “welfare mother” in terms that were clearly meant to imply race.

Many scholars in subsequent decades have questioned whether social conservatives had actually been tricked into voting for politicians who represented the interests of the wealthy and corporations while offering little support for social issues. Reagan had been president of the Screen Actors Guild and could hardly be counted on to support tougher censorship laws. As governor of California, Reagan had supported a reproductive rights law that removed barriers on abortions. Although he relied on the support of pro-life groups, once President, Reagan avoided direct action on the controversial subject of abortion. He also did little beyond offering verbal support for socially conservative causes such as school prayer.

Some observers were surprised that Evangelicals would support a candidate such as Reagan, a divorced Hollywood actor who did not attend church. In contrast, Jimmy Carter was a born-again Christian. However, Evangelicals understood that Carter did not believe that his personal religious ideas should influence policy and he generally supported the more liberal views of his Democratic supporters. In addition, many working-class voters supported Reagan’s proposed tax cuts, believing they would result in domestic job creation. Although their reaction confounded many liberals, cuts to welfare were also popular with the working-class voters because welfare had failed to eliminate poverty and seemed in many cases to offer a disincentive to work. Finally, in the wake of scandals involving union leaders such as Jimmy Hoffa, many social conservatives were also hostile toward unions.

Although he did little to further socially conservative causes through legislation, Reagan took immediate action against unions. One of Reagan’s first actions as president was to fire more than 10,000 federal air traffic controllers who were part of a union that was striking for a pay increase. Reagan replaced these workers with military personnel on active-duty orders, a move that quickly destroyed the strike and the union. Reagan also supported employers who used similar measures to crush labor activism. And yet 40 percent of union members still voted for Reagan over the Democrat Walter Mondale in 1984. Reagan and other conservatives also supported measures that lowered taxes for corporations and supported free trade policies that made it easier for US companies to open factories in foreign countries. By 1986, Reagan had slashed tax rates for the wealthy by more than 50 percent without similar cuts for the middle and lower classes. Although it confounded many Democrats, Reagan retained the support of many union voters and lower-income Americans through his second term.

Women and the New Right

Women had composed both the leadership and the rank-and-file of the New Left. The role of women was equally as important to the New Right during the 1980s. Mobilized in opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), conservative women mirrored some of the tactics and organizational structure of civil rights activists. Conservative women leaned heavily on the church and other institutions, and also mirrored the organizational structure of previous social movements. The names of conservative women’s groups reflected their belief in traditional notions of family and gender. Women Who Want to be Women (WWWW) and Happiness of Motherhood Eternal (HOME) were two such organizations. Conservative women viewed the rapprochement of straight and lesbian activists within the feminist movement, along with recent decisions by the Supreme Court upholding abortion laws and banning school prayer, as proof that they were waging a war against the ungodly forces of both Sodom and Gomorrah.

Reagan’s nomination of Sandra Day O’ConnorAn attorney originally from El Paso, Texas, Sandra Day O’Connor became the first female Supreme Court justice in 1981. encouraged conservative women, less as a symbol of women’s advancement as the first woman to join the Supreme Court than the hope that O’Connor would reverse Roe v. Wade. Despite her conservatism, O’Connor and other Supreme Court justices upheld the legality of abortion in a number of cases, although they did support an increasing number of restrictions to the procedure. Many conservatives and Evangelicals felt betrayed by the Republican Party and began organizing direct protests against abortion providers.

Figure 13.4

Sandra Day O’Connor became the first woman on the US Supreme Court. Because she had a conservative orientation, many of the president’s supporters among the New Right hoped she and other Reagan appointees might overturn Roe v. Wade.

Thousands of antiabortion activists descended on Wichita, Kansas, under the auspices of a group called Operation Rescue in 1991. The majority of the participants in the self-labeled “Summer of Mercy” were women, many of whom physically blocked the entrances to abortion clinics and were among the 2,000 protesters who were arrested. At the same time, many conservative and evangelical women who opposed abortion also opposed the aggressive tactics of Operation Rescue. This was especially true of the individuals who harassed and even murdered abortion providers that summer. More representative of the conservatism of women during this period were the hundreds of thousands of local women who led community organizations that sought encourage single mothers to consider adoption. Others joined organizations that sought to ameliorate some of the social changes they felt had led to increases in the number of single mothers. Other conservatives sought to prevent drug addiction, crime, and pornography, and to reverse societal toleration for obscenities in Hollywood.

Protests against an increasingly secular popular culture raised questions regarding traditional modes of gender-based divisions of labor in modern families. For millions of women, a life dedicated to family was an important and fulfilling vocation, a dignified calling they feared the feminist movement sought to slander. Books written by conservative homemakers and career women alike proliferated during the 1970s and 1980s. For example, Helen Andelin’s Fascinating Womanhood sold millions of copies and launched a movement that inspired thousands of women to create and attend neighborhood classes and discussion networks. Andelin believed that the ideal family was one of male leadership and provision alongside female submission and support. Andelin asked her readers to consider what traits made them desirable to their husbands and strengthen their marriages by finding ways to increase this desire and better serve their husband’s needs. Although historians might question the accuracy of the author’s claims that this patriarchal model was ever typical in any era of American family life, Andelin described a mythical past that most Americans believed had existed. For millions of conservatives seeking a return to a bygone era, it naturally followed that the family should seek a return to traditional arrangements based on paternal leadership.

Other conservative women criticized Andelin as promoting a fiction that more resembled the 1974 novel The Stepford Wives than a well-adjusted family. Many conservative women simply sought to counter the image that stay-at-home mothers were somehow naive or victimized. These women agreed that gender discrimination did limit the options of women in the past and believed that women should be free to pursue careers. However, these women also feared that elevating the dignity of women in the workforce had at least unintentionally led many to question the dignity of labor within the home. Not all who espoused a return to traditional modes of gender and family were conservatives or Evangelicals, and many women who had enjoyed successful careers outside the home reported their equal happiness as homemakers. These women hoped to encourage the recognition that many “traditional” couples were genuine partnerships based on mutual respect.

However, for millions of US families, the tradition of women not working outside the home was not economically feasible. By the early 1980s, the majority of married women worked both inside and beyond the home. Many found the experience to be anything but liberating. While these women recognized that gender discrimination limited their career options, they aggressively countered notions that homemaker was a career of last resort. One of the leading criticisms of these women against the idealized superwoman of the 1980s who balanced career and family was related to the sacrifices such balancing required. Sociologists labeled the added burden of career and family the “second shiftA phrase connoting the added burdens of married women with full-time careers who were still expected to fulfill the domestic responsibilities of a homemaker and parent.,” reflecting the frustration of women who found that their husbands seldom agreed to share domestic responsibilities, even though wives were increasingly likely to work the same number of hours outside of the home.

“Reaganomics” and its Critics

Income tax in the United States historically followed the doctrine of progressive taxation, creating tax brackets that increase as an individual earns more money throughout the year. For example, a physician making $200,000 might have the majority of her income taxed at 40 percent, while a firefighter who made $35,000 would be taxed at 20 percent, and a college student working part time who earned only $5,000 might pay no federal income tax at all. For Reagan, the progressive tax structure was responsible for the persistence of America’s economic problems. As a Hollywood actor in an era where taxes on those with large salaries was very high, Reagan saw more and more of his income go to taxes as his annual earnings increased. After producing a couple of films each year, any additional money Reagan might make could be taxed at rates approaching 90 percent when adding California’s state tax to the federal rate. In response, Reagan chose to make only a handful of films each year.

Reagan drew heavily from his experience as an actor in many aspects of his presidency. In the case of tax policies, the president believed that high tax rates discouraged other talented and successful individuals in their chosen fields from making a maximum effort each year. In his field, it might mean fewer movies. However, if entrepreneurs and financiers followed a similar strategy, then high taxes would constrain economic growth. Believing in a sort of economic Darwinism, Reagan argued that the best way to encourage job creation was to reduce the taxes for high-income Americans because these elites had demonstrated a talent for creating wealth. The wealthy, Reagan argued, could be expected to use their money to produce more wealth through investment and innovation that would spur job growth for everyone else. To this end, Reagan’s Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 reduced the top tax bracket from 70 to 50 percent while slashing taxes paid by corporations.

The super wealthy were not the only beneficiaries of Reagan’s tax cuts, which led to an overall reduction of tax rates by 30 percent throughout his first term. More controversial was the reduction in inheritance taxes. These taxes were not based on earned income, but rather taxed the transfer of wealth from one generation to another. These taxes had inspired many of the richest Americans to donate their fortunes in previous decades. As a result, removing the inheritance tax was much harder to justify in terms of economic stimulus.

Figure 13.5

President Reagan discusses a chart that portrays his tax plan as offering substantial savings for the average family. In reality, Reagan’s tax policies favored the wealthy and corporations, something the president’s supporters believed would result in greater overall economic development.

In his second term, Reagan passed the most sweeping changes to the tax code since the Sixteenth Amendment established the modern system of federal income tax. The Tax Reform Act of 1986A sweeping tax reform law that simplified the tax code and eliminated some tax shelters and other methods that had been used in the past to hide income or illegally reduce one’s tax burden. The law reduced the top tax rates wealthy individuals paid from 50 percent to 28 percent, while raising the minimum tax rate to 15 percent lowered the highest tax bracket from 50 percent to 28 percent while increasing the minimum rate from 11 percent to 15 percent. The reform also eliminated many of the various tax brackets between these rates, meaning that most Americans either paid 15 percent or 28 percent. A few provisions helped the poor, such as a cost-of-living adjustment to the amount of money that was exempt from taxation so that those living below the federal poverty level no longer received a tax bill. Other reforms eliminated various tax shelters for individuals, although many of these ways of hiding income remained for corporations. The law also required parents to list the social security numbers for each dependent child they claimed for tax purposes, eliminating the ability of individuals to increase their tax deductions through fraudulently listing imaginary dependents. As a popular economist has shown, the reform led to the disappearance of 7 million “children” on April 15, 1987.

Reagan’s tax cuts reduced federal revenue by hundreds of billions of dollars each year. This reduction of income could only be offset by equal reductions to the federal budget, borrowing money, or a massive economic boom that created so much taxable wealth that the government still took in more money each year. Reagan promised the latter would occur—the result of an unfettered economy free from aggressive taxation and government regulation. Reagan also proposed significant budget cuts to Social Security and Medicare, just to make sure that the federal budget could be balanced while the nation awaited the economic bonanza he believed his tax cuts would produce. However, cuts to Social Security and Medicare provoked outrage, and Reagan quickly reversed course. In the end, the president approved a budget that was similar to previous years except with massive increases for the military.

Reagan’s defense budgets continued to grow each year, doubling the annual budget to an incredible $330 billion by 1985. As a result, many challenged the president to identify exactly how he would fulfill his promise to reduce the nation’s indebtedness. Even Reagan’s budget director admitted that his administration’s economic projections were based on an optimistic faith that reducing taxes for the wealthy would “trickle down” to the middle and lower classes through job creation. This confidence in supply-side economicsAn economic theory that suggests government policies should be geared toward keeping revenue and economic decisions in the hands of businesses and consumers. While Keynesian economics suggests using the federal government to stimulate growth through a variety of measures, supply-side economics suggest lowering taxes and regulations on business and trade as ways of stimulating the economy. that emphasized government intervention to spur growth and investment through tax reduction was certainly not a new idea. However, because the Reagan administration pursued the principles of supply-side economics with such vigor, the basic theory that increasing the wealth of the wealthy would eventually trickle down to the rest of the nation became known as “Reaganomics.” Critics of the president used other monikers such as “voodoo economics” to describe Reagan’s theories.

Supporters of Reagan’s belief in supply-side economics point out that the Dow Jones Industrial Average—a measurement of the value of the 30 largest companies in the United States—tripled during the 1980s. Inflation fell from over 10 percent when Reagan took office to less than 4 percent, while unemployment fell from 7 percent to just over 5 percent. Critics of Reagan point to the increasing disparity between the rich and the poor that also accelerated during the 1980s as being the real consequence of Reagan’s regressive tax policies. They also disagree that tax cuts for the wealthy created jobs, pointing out that the percentage of jobs that paid wages above the poverty level had declined. Critics agree that tax cuts for corporations provided additional revenue for investment, but argue that much of this investment had been used to create manufacturing facilities in other nations.

Although the president’s critics usually concede that Reagan’s tax cuts and military spending did spur the economy and create some jobs in the short run, they argue that they did so only by borrowing massive sums of money. The size of the national debtThe total amount of money that a nation presently owes its creditors.—the cumulative total of all the money the federal government owes—tripled from $900 billion to nearly $3 trillion in only eight years. Between the start and conclusion of the Reagan administration, the United States had gone from being the leading creditor in the world to the most indebted nation in the world.

Previous administrations tolerated deficit spendingThis occurs when a government borrows money to finance its operations.—the practice of borrowing money to make up for the amount the government overspent in one particular year. However, the amounts the government borrowed were usually quite small unless the nation was at war. After the 1930s, some government borrowing was also accepted in times of financial crisis as a way to spur the economy. Neither scenario applied to the eight peaceful years of Reagan’s presidency, yet the government accumulated a debt that was three times greater than the combined annual deficits of the past two centuries. And contrary to the tradition of repaying the debt, deficits and debt continued to grow at the same pace when former vice president George H. W. Bush took office. The interest on the debt alone quickly became the largest non-defense-related federal expenditure. As a result, any effort to reduce the national debt could only be achieved after balancing the budget and paying hundreds of billions of dollars in interest.

Political candidates are known for making sweeping promises, yet the question of whether Reagan kept his pledge to restore the strength of the US economy remains an item of fierce debate. Democrats are quick to point out that Carter’s decision to halt inflationary measures as well as the normal business cycle were part of the reason the economy recovered during the 1980s. Reagan’s critics also contrast his promise of fiscal responsibility and smaller government with the tripling of the national debt and the expansion of the federal government, which grew in terms of both budget and the number of federal workers. Furthermore, President Reagan never submitted a balanced budget, and even the debt projections that came from his budget office were too optimistic.

Reagan himself usually deflected the criticisms of his economic policy in a good-humored manner that undermined some of his critics. “You know economists,” he would respond, they “see something that works in practice and wonder if it works in theory.” Reagan even seemed impervious to an assassin’s bullet that ricocheted and lodged near his heart in March 1981. The unfazed president thanked nearby secret servicemen for their service and even joked with surgeons by asking if they were Democrats before they removed the bullet. Most Americans lacked a sophisticated understanding of supply-side economics, but they knew the economy had floundered under Carter and was recovering under Reagan. Questions regarding the long-term wisdom of Reagan’s policies continue to engage historians and pundits alike, with responses usually reflecting both economic theory and one’s political orientation.

Wall Street and the S&L Bailout

While deficits would not be felt for many years, government deregulationDeregulation is the reduction or elimination of laws previously enforced on a particular industry. of various industries would have a more immediate impact on the economy during the 1980s. Democrats and Republicans alike approved the elimination or reduction of government price controls during the 1970s and 1980s. Nixon removed price controls of oil and natural gas in response to the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) embargo, and Carter eased price controls and regulations governing the transportation industry. Reagan accelerated this trend, believing that most forms of federal regulation, including consumer and environmental protection laws, hampered business growth. In contrast to the Department of Defense, who was told by the president to “spend what you need,” Reagan slashed the budgets of federal agencies like the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). More disturbing to environmentalists, the EPA reinterpreted the Clean Air Act and other laws in a way that was so favorable to industry that an investigation was conducted. The inquiry revealed that twenty administrators in the EPA had each accepted corporate bribes.

Because utility companies were public utilities and had a natural monopoly in the communities they served, these industries had been heavily regulated. However, Reagan reduced these regulations in hopes of increasing competition and reducing prices. Airlines and other common carriers were treated much the same way, with the federal government transferring the control over prices to the executives of these companies and the free market. Energy prices and airfares fluctuated according to market forces following deregulation. These reforms led to mostly lower prices in air travel, but also led to numerous difficulties for utility consumers in some markets.

While the results of deregulation were mixed in most industries, the deregulation of the financial industry led to complete disaster. Banks known as savings and loan institutions (S&Ls) had a reputation for safety because they followed strict rules regarding the ways they could invest their depositors’ money. Chief among these rules was the provision that S&L loans be backed by collateral such as a home mortgage. However, interest rates were at record highs during the early 1980s, and the Reagan administration agreed to ease these restrictions and permit S&Ls to make riskier loans. By the late 1980s, hundreds of the S&Ls were facing bankruptcy due to bad loans and a decline in the real estate market.

Because S&Ls were part of the banking system, each depositor’s savings accounts were insured by the federal government. As a result, the government was forced to pay more than $150 billion in federal bailouts to make sure families and businesses that deposited their money were protected. Although both parties approved the deregulation of the banking and investment industry, the resulting failure of many leading financial institutions and resulting Savings and Loan BailoutAs a result of deregulation and bad investments by banking institutions known as savings and loan institutions, the government paid out at least $150 billion to holders of insured deposit accounts at these institutions. of the late 1980s and early 1990s was blamed almost solely on the Republican Party. Given Republican efforts to lower corporate taxes and the tendency for Republicans to be the most enthusiastic supporters of deregulation, it is easy to see why most Americans blamed the party of Reagan when deregulation led to default. However, many of the congressmen who approved the deregulation and were later investigated for accepting illegal donations from members of the banking industry were Democrats.

The Department of the Interior had been insulated from controversy since the Teapot Dome Scandal of the 1920s. However, Reagan appointee and secretary of the Interior James Watt kept his agency in the headlines throughout the 1980s. One of Watt’s comments regarding his religious beliefs were regularly quoted out of context by the political left in an attempt to discredit the secretary as well as other religious conservatives. During his Senate confirmation hearing, Watt responded to a question about long-term preservation of resources by stating that he did not know how many generations would pass before the return of Christ but that Americans must shepherd their resources for future generations until that time.

Many on the left at the time reported that Watt had suggested environmental policies did not matter because the end of the world was nigh. Watt himself was fond of misrepresenting the words of his opponents and had earlier declared that there were only two kinds of people in the United States: liberals and Americans. This war of words did not mask the actions of Watt’s department for long, as nearly two-dozen high-ranking officials were forced to resign for improper actions. In addition, several officials were convicted of accepting bribes or other ethics violations. Similar to the Teapot Dome Scandal, Department of the Interior officials permitted oil and timber companies to lease, log, mine, drill, and otherwise commercially develop millions of acres of previously protected areas of the federal domain at prices that were often far below estimated market value. One of the most immediate results was the growth of environmental interest groups such as the Sierra Club, whose protests resulted in some areas of the federal domain again being declared off limits to developers.

The Reagan administration also approved a wave of corporate mergers that consolidated vital industries in the hands of a few companies. Critics protested that the government-approved mergers created monopolies. The architects of these deals argued that the mergers created stronger and more efficient businesses. Other practices that were common throughout the 1980s, such as leveraged buyouts, increased the risks to the entire financial system. These leveraged deals permitted a group of investors to purchase a controlling stake in a publicly traded company by using loans to purchase shares. In addition, these investors often secured the loans by using the stock they had just purchased on credit as collateral. As a result, a small drop in the price of any particular stock could bankrupt an entire company and send shockwaves throughout the financial system.

This is precisely what happened on October 19, 1987, when Wall Street experienced the worst crash in its history. Although the market had risen quickly in proceeding years due to speculation, these gains were erased in a single day when the Dow Jones average fell over 20 percent. Companies such as RJR Nabisco that participated in the leveraged buyouts were forced to lay off thousands of employees, yet the CEO of the company received over $50 million in compensation. Brokers that facilitated these and other risky strategies, such as junk bond investor Michael Milken, earned over $500 million in 1987 alone. Unlike previous Wall Street financiers, such as JP Morgan, Milken’s deals did not support economic growth by matching legitimate entrepreneurs with investors. Instead, Milken’s incomes were commission-based, which led him to violate federal laws in order to increase the volume of his transactions. Milken served only two years of a ten-year prison sentence and remains one of the wealthiest men in America.

Accompanying many of these high-stakes mergers was the dreaded news of “restructuring” that often meant the loss of jobs for the employees of the affected corporations. For those in manufacturing, restructuring was often a code word for laying off employees to save money. Sometimes restructuring meant that a company was preparing to close a factory in the United States in favor of another country where operating costs were lower. At other times, it simply meant laying off full-time employees with salaries and benefits and replacing them with low-wage hourly workers.

Even privately owned companies that had historically offered high wages to their employees, such as Levi Strauss & Co., soon adopted these strategies. In some cases, these companies had no choice if they wanted to stay competitive. At other times, these measures were simply used to enhance profitability. Levi’s blue jeans were the most recognizable American fashion; yet between the early 1980s and 2003, each of the dozens of US Levi’s factories was closed. Each announcement resulted in thousands of workers losing jobs that were relatively well paying. Although what was happening at Levi Strauss & Co. was typical of the clothing industry, the fact that the United States no longer produced Levi’s came to symbolize the US trade imbalance, which grew to $170 billion by 1987.

Review and Critical Thinking

- Why might the political orientation of the nation have become more conservative during the 1980s than other decades? What role did Evangelicals and women play in this transition? How might one argue that the 1980s were actually not any more or less conservative than previous eras in US history?

- Why might Evangelicals support Reagan over Carter? What about union members and blue-collar workers? Were these individuals “fooled” by Reagan’s use of social issues, or is this an unfair characterization?

- What role did women play in the New Right? How did feminism affect the rise of the New Right? What arguments were made in support of and against the introduction of equal rights amendments to state constitutions? Look up the Equal Rights Amendment, and explain your position on the proposed law in relation to these arguments.

- What was Reaganomics, and how did it differ with other theories, such as Keynesianism? Why did so many Americans support tax breaks for the wealthy and corporations during the 1980s?

- Were the 1980s a second Gilded Age? Explain your position using specific historical examples.

13.2 The End of the Cold War

Learning Objectives

- Summarize the Iran-Contra Affair with an explanation of the Reagan administration’s intent and the various details of the scandal.

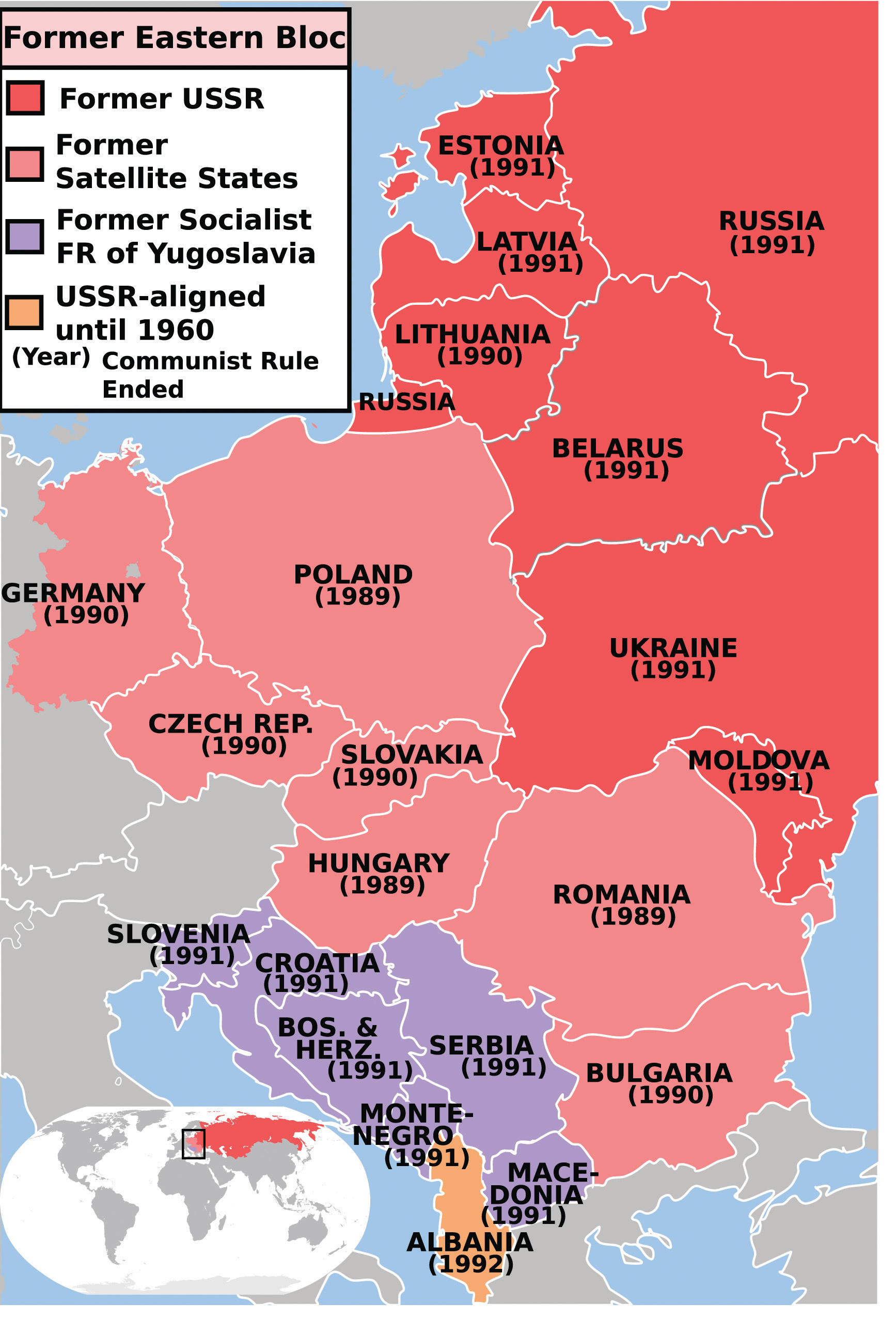

- Explain the Reagan Doctrine and how it applied to foreign affairs in Latin America, the Middle East, Africa, and Afghanistan.

- Summarize the diplomatic history of the 1980s as it applies to US-Soviet relations and the fall of Communism. Explain the significance of anti-Communist protest in Eastern Europe and the fall of the Berlin Wall.

President Ronald Reagan’s top priority while in office was related to international affairs. He was not satisfied with containing Communism, but instead sought to “roll back” its influence throughout the globe. Reagan’s style of leadership emphasized leaving the execution of his ideas and policies to others. The president’s strategy regarding world affairs, dubbed the Reagan DoctrineA guiding force in Reagan’s foreign policy, the Reagan Doctrine suggested that the United States must support the armed forces of any regime that was waging war against Communist forces., likewise relied on finding allies who were willing to support his anti-Communist worldview rather than directly deploying US forces. As a result, the heart of the Reagan Doctrine was the president’s announcement that the United States would provide aid to all groups fighting against Communist forces worldwide. Supporters of the Reagan Doctrine pointed out that military aid and covert CIA operations resulted in anti-Communist victories without risking large numbers of US troops or repeating the experiences of Korea and Vietnam. Critics feared that these covert operations may have unintended consequences similar to the Bay of Pigs Invasion and the 1953 coup that placed the shah of Iran in power. Others pointed out that many of the recipients of US military aid, such as the Nicaraguan Contras and the Afghan Mujahedin, used methods and maintained beliefs that many Americans opposed.

Middle East and Afghanistan

Figure 13.6

President Reagan meets with leaders of Afghan forces opposed to the Soviet Union in 1983.

These conflicts and internal contradictions were especially troublesome in the Middle East, where Cold War tensions coexisted with historic rivalries between East and West. The ease with which Egypt was able to play the United States and Soviet Union against one another during the Suez Crisis demonstrated the fragility of détente in the region. Tensions rose even further in the late 1970s as the Soviets hoped to regain influence in the Middle East by supporting a number of Marxist regimes along the Red Sea in East Africa and in neighboring Afghanistan. In the spring of 1978, Communists in Afghanistan temporarily seized power with the aid of the Soviet Union. However, this government proved unpopular with the majority of the Afghan people, partly due to its support for women’s rights and other liberal and secular reforms. For the Afghans, this secular and pro-Soviet regime seemed much like the pro-Western government of Iran that had just been overthrown by the Muslim cleric Ayatollah Khomeini.

The Soviets and Americans were stunned. In just one year, religious leaders in Iran had expelled the US-backed shah and Islamic rebels were engaged in a civil war that threatened to overthrow the pro-Soviet government of Afghanistan. If the Islamic Afghan rebels prevailed and started their own government, the Soviets feared, they might also follow the Egyptian model of expelling Soviet military advisers in return for US aid. If this happened, some Soviet leaders feared, Afghanistan might form a deal with the West that might someday lead to the construction of US missile bases along the Soviet border.

Applying their own version of the domino theory, Soviet leaders responded to the growing Afghan Civil War by sending 75,000 troops to support the pro-Soviet regime. With little understanding of the history, geography, religion, or culture of Afghanistan, Soviet leaders predicted that their troops would return within a month after crushing all resistance to the Communist government in Kabul. Instead, the Soviet Invasion of AfghanistanBegan on Christmas Day in 1979 and lasted for a full decade. The Soviet Union was attempting to prop up an unpopular Communist government in Afghanistan against the wishes of the majority of the Afghan people. The armed uprising against the Soviet military was led by Islamic fundamentalists who were backed by the United States. resulted in a decade-long war between Soviet troops and Islamic rebels, some of whom were supplied by the United States. US leaders backed a variety of Islamic rebels in hopes of making Afghanistan resemble the quagmire of Vietnam for Soviet forces. In the end, neither the Soviet Union nor the United States made significant efforts to discern the ideas and needs of the Afghan people, spending millions of dollars to arm the enemies of their rival without considering the long-term consequences of a potentially short-sighted action. Just as the US-aligned South Vietnamese government fell shortly after US forces withdrew, the nominal government of Kabul was quickly overrun by MujahedinIslamic guerilla warriors in Afghanistan who fought against and ultimately repelled the Soviet Union’s invasion of their country. America’s support of the Mujahedin was the result of the Reagan Doctrine’s support of any force that was fighting against Communist forces. Because some of the more radical leaders of the Mujahedin later advocated similar confrontation against the West, the decision to provide weapons to Islamic guerillas has been a source of controversy in recent years. rebels after Soviet forces withdrew in 1989. Before and after the fall of Kabul, Afghanistan was effectively governed by various rebel forces that became increasingly distrustful of both the Soviet Union and the United States.

As one Soviet political scientist later explained, Moscow’s decision to invade Afghanistan was the product of its recent success using the military to sustain corrupt and unpopular Communist regimes in other nations. “In politics if you get away with something and it looks as if you’ve been successful, you are practically doomed to repeat the policy,” Soviet scholar Georgy Arbatov explained. “You do this until you blunder into a really serious mess.” Arbatov believed that Soviet leaders became the victims of their own “success” in ways that paralleled the path that led to America’s decision to use the CIA to sustain unpopular and corrupt right-wing governments. While the long-term “success” of US covert operations in Latin America and the Middle East might be dubious at best, in the short term, US companies made record profits and US consumers enjoyed low-cost imports of coffee, bananas, and oil. Armed with hindsight, it appears that Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan and Eastern Europe thwarted potential anti-Communist revolutions in the short term. In the long-term, however, it led to costly interventions that bankrupted Moscow and diminished the international prestige of their government in ways that contributed to the fall of Communism and the Soviet Union itself.

The Soviets might have reconsidered their decision to invade Afghanistan if they had a more thorough understanding of Afghanistan’s own history of resisting conquest. Similar lessons from history might have informed US policy regarding the Iraq-Iran WarA war between Iraq and Iran that began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran in September 1980 and lasted until an armistice in 1988. The invasion occurred in the wake of the Iranian Revolution, and as a result, the United States provided tentative support to Iraq due to the belief an Iranian victory would be contrary to America’s strategic interests in the Middle East., which erupted in September 1980. Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein hoped to capitalize on instability in the region following the Iranian Revolution and the declining support of Egypt in the Arabic world following its recognition of Israel. In addition, the Iraqi leader feared that the revolution that had led to the ousting of Iran’s secular dictator would spread to his country. Hussein hoped that a quick and successful invasion of Iran—a rival dating back centuries—would lead to renewed Iraqi patriotism and greater popular support of his own regime. Hussein’s decision was also calculated on the response of the United States. In the wake of the Iranian hostage crisis, Hussein understood that there was little chance that America would support Iran.

Iran possessed a number of modern weapons systems that it had purchased from the United States during the era when the US-backed shah of Iran was in power. These arms sales ended when the Islamic cleric and fiercely anti-Western Ayatollah Khomeini seized power in 1979. As a result, Iranian forces were in desperate need of US supplies to repair and rearm many of their American-made weapons. However, the possibility of an Iranian victory terrified many Western leaders and led the United States to provide direct and covert aid to Iraq. Reagan sent Donald Rumsfeld to Baghdad in preparation for possible resumption of normal diplomatic relations. The Reagan administration chose to minimize Iraq’s use of chemical weapons. It also helped to derail efforts of the United Nations to condemn Hussein for atrocities committed against Kurdish people in Iraq, many of whom were being recruited by the Iranians who hoped to start a popular uprising against Hussein.

Concerns about an Iranian victory led the Reagan administration to ignore many of the atrocities committed by Hussein. The same was not true of Libyan dictator Muammar el-Qaddafi. In 1986, Libyan terrorists planted a bomb that killed two US soldiers in West Berlin. Reagan responded with a series of air raids against military and governmental targets in Libya that killed a number of military personnel and civilians but failed to harm Qaddafi or alter his support of terrorist networks. The use of terrorismUsing violence or the threat of violence against innocents in an attempt to achieve a certain outcome or spread fear for political purposes. against the US had become more frequent during the early 1980s. For example, Islamic jihadists bombed a garrison of US Marines in Beirut, Lebanon, in October 1983. This attack instantly killed 241 servicemen who had been acting as peacekeepers in a conflict regarding Lebanon and Israel. Reagan made little effort to retaliate against these Jihadists. Instead, he simply withdrew US forces from Lebanon.

Figure 13.7

The remains of the US Marine barracks in Beirut, Lebanon, following a terrorist attack that instantly killed 241 US troops.

In addition, a violent anti-Jewish faction named Hezbollah that was supported by Iran and other Arabic nations captured a number of American hostages. Iranian officials were approached by American operatives who hoped to secure the release of the American hostages. At this point, Reagan violated his own pledge that the United States would never negotiate with terrorists. The Reagan administration brokered a deal whereby the United States agreed to sell arms to Iran to secure release of American hostages held by the Lebanese terrorists. However, only a few hostages were actually released, and the arms sales likely encouraged the subsequent capture of more American hostages.

In 1986, some of the details of these “arms-for-hostages” deals were uncovered and publicly released by Middle Eastern journalists. The Reagan administration initially denied that any deal was made with Iran. However, these journalists uncovered more evidence, which forced a number of high-level US officials to resign in disgrace. Reagan himself denied direct knowledge that the weapons sales were part of any bargain with the terrorists, admitting only that he had failed to detect and prevent members of his administration from carrying out the deals. “I told the American people that I did not trade arms for hostages,” Reagan explained in a partial confession. “My heart and best intentions still tell me that is true, but the facts and the evidence tell me it is not.” While Reagan’s popularity temporarily declined, the confessions of several of his aides prevented special investigators from finding any clear evidence that Reagan had personally ordered the deals. Ironically, the success of Reagan’s detractors in creating an image of an aloof president who allowed his staff to make decisions on their own helped to corroborate the president’s defense. However, these weapons sales to Iran would soon play a major role in a larger scandal known as the Iran-Contra Affair.

Latin America and the Iran-Contra Affair

Reagan would earn a reputation as a diplomatic leader who helped to facilitate a peaceful end to the Cold War in Europe. However, the Reagan administration pursued a very different strategy when it came to Latin America. Reagan reversed Carter’s policy of only aiding anti-Communist groups that supported democracy, resuming the supply of American military aid to right-wing dictators and paramilitary forces throughout the region. If the risk was small enough, Reagan was even willing to send US forces to directly remove a left-wing government. For example, a left-leaning and pro-Castro government seized power on the tiny Caribbean island of Grenada in 1979. The Reagan administration feared that Soviet missiles might be placed on the island. In 1983, the island’s government switched hands and US officials viewed the resulting instability as an opportunity to intervene. Under the pretext of concern for the safety of US students attending a private medical school, thousands of marines landed on the island in October 1983. Within three days, the island and its 100,000 residents were firmly under US control and a new government was formed.

The Invasion of GrenadaOn October 25, 1983, 7,000 US soldiers overwhelmed and seized control of the island of Grenada. The invasion was in response to a similar action by Marxist rebels who had earlier seized control of Grenada’s government and were perceived by the United States as installing a Communist government aligned with the island of Cuba and the Soviet Union. led to international condemnation of the United States. The United Nations Security Council voted 11-1 to condemn the US action, with the American representative casting the single vote in opposition. Reagan’s supporters pointed to the fact that only eighteen US troops were killed in the conflict. They also pointed out that the operation had succeeded in its goals to protect US citizens on the island, prevent a possible civil war, and replace a pro-Soviet regime with one that is friendly to the United States. Opponents on the left viewed the action as imperialistic. Others feared that the unilateral action against a member of the British Commonwealth might strain relations with London and other nations because US leaders made no effort to consult with British or Caribbean leaders.

Leaders throughout the region condemned the invasion of Grenada, but many were more concerned with the US intervention in Central America. The Somoza family operated a dictatorial government that operated Nicaragua like a police state. The United States had supported the Somoza dictatorship until the late 1970s when the Carter administration withdrew American support. Without US aid, the Somoza family was ousted by a popular revolution in Nicaragua that was led by a group of Marxist rebels known as the SandinistasSupporters of the Socialist Party of Nicaragua that controlled the government of that country during the 1980s but were engaged in a civil war with counterrevolutionaries known as “Contras” in the United States.. The Sandinistas were generally supported by the people of Nicaragua, but frequently resorted to violence and imprisonment against those who sought a return of the Somoza regime. Reagan and his advisers decided that making distinctions between totalitarian and humanitarian regimes that opposed Communism was a luxury the United States could not afford. This decision simplified US efforts to roll back Communism by encouraging the United States to simply provide weapons to any Latin American dictator or counterrevolutionary regime that opposed the Sandinistas. However, this compromise also led to one of the darkest legacies of the Reagan Doctrine.

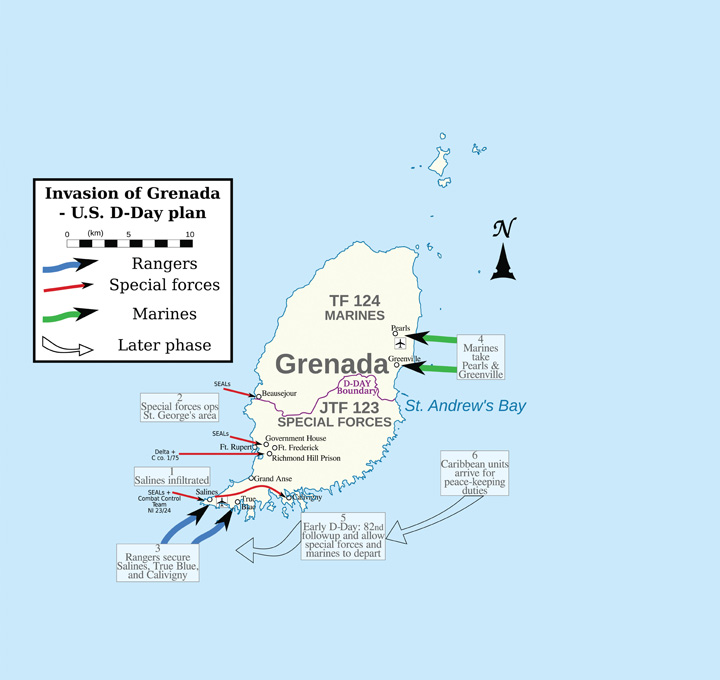

Figure 13.8

A map showing the routes taken by US troops during the invasion and occupation of the Caribbean island of Grenada.

Under Reagan’s leadership, the United States renewed its support for a repressive but anti-Communist dictatorship in neighboring El Salvador. In exchange, the Salvadoran government increased its efforts to eliminate leftist forces in its own country who were backed by Cuba and the Nicaraguan Sandinistas. El Salvador’s military government likely used some of this aid to further the work of its notorious “death squads.” These units traveled the Salvadoran countryside and killed everyone suspected of being a Marxist or aiding the rebels. The United States also provided massive aid through the CIA to Nicaraguan counterrevolutionaries (nicknamed ContrasGuerilla fighters who opposed the Socialist Party of Nicaragua and were aided by the United States. US support of the Contras has remained controversial because of the methods used by the Reagan administration to provide covert aid in violation of US law and because of the connections of many Contra leaders with leading drug traffickers) who sought a return of the Somoza dictatorship. Because of their willingness to fight the pro-Soviet Nicaraguan government, Reagan hailed the Contras as “freedom fighters.” Reagan had applied the same label to the anti-Soviet Mujahedin in Afghanistan. Most Americans, unfamiliar with Latin American affairs and supportive of their president, simply accepted Reagan’s definition of the Contras as the “good Latin Americans.” The US military soon established multiple bases throughout the region. In fact, critics labeled Nicaragua’s northern neighbor the USS Honduras due to the large number of US troops that were present.

Later revelations would lead many to question the assumption that the Contras were fighting for the freedom of Latin America. In addition, the Reagan administration became increasingly involved in a number of illegal and covert actions that would lead to an investigation of the president and the resignation of several top officials. The entire scandal was labeled the Iran-Contra AffairA scandal involving the Reagan administration’s covert sale of about 1,500 missiles to Iran in a failed attempt to secure the release of seven hostages. Excess proceeds from the sale were covertly provided to the Contras in Nicaragua. These deals not only violated US laws and constitutional concepts regarding presidential authority, they may have encouraged other terrorist groups to take American hostages.. As the name implies, the Iran-Contra Affair involved events in Nicaragua as well as the Middle East.

The Reagan administration’s troubles began in 1982 when Congress refused to continue providing military aid to the Contra rebels in Nicaragua. Many in Congress questioned the assumption that the Sandinistas presented a threat to US security. Others questioned the morality of supporting the oppressive Somoza and Salvador regimes. In September 1982, Congress approved the Boland Amendment, prohibiting US officials from providing aid to the Contras. Aware that US funds were still being covertly funneled to the Contras, Congress approved a second ban on funding the Contras in 1984.

Despite both of these laws, the Reagan administration continued to provide weapons and money to the Contras through a variety of legal and illegal methods. For example, the money the government had earlier received from its secret arms sales to Iran in exchange for the promised release of US hostages had been hidden from Congress and the public. The Reagan administration determined that these funds should be used to covertly supply the Contras with weapons. In addition, the Reagan administration still provided weapons and money to surrounding Latin American dictators. Many of these leaders funneled the American supplies and weapons to the Contras because they feared a Sandinista victory might encourage revolutions in their own nations. Unlike the covert aid that the Reagan administration secured with the proceeds of the Iranian sales, this method of arming the Contras violated the spirit and not the letter of the Boland Amendment.

Figure 13.9

This 1985 political cartoon was critical about Reagan’s denial of personal culpability regarding the Iran-Contra Affair. In the first panel an actor claims “it didn’t happen,” which is labeled “Iran-Contra, take 1.” In the second panel an actor claims “it happened, but I didn’t know,” only to later exclaim “I might have known, but I don’t remember.”

The Reagan administration also responded to what it viewed as congressional meddling by launching a public relations campaign that sought to present the Contras as freedom fighters and the Sandinistas as anti-American. The government rewarded pliable journalists who agreed to publish a variety of accusations against the Sandinistas. These articles led more and more Americans to agree with the government’s position on Nicaragua. In response, Congress eventually agreed to lift its ban on providing the Contras with weapons. However, this aid was quickly rescinded when it was discovered that the Reagan administration had been secretly using government funds to support the Contras all along.

The Reagan administration came under fire in 1984 when it was discovered that the CIA had placed mines in the harbors and rivers of Nicaragua. Even the archconservative Barry Goldwater responded with anger, calling the CIA’s actions an unjustifiable act of war. The United Nations condemned the action, and the World Court demanded that the United States apologize and pay reparations. However, the United States was able to use its veto power to thwart any action by the UN Security Council. US Ambassador to the United Nations Jeane Kirkpatrick responded by pointing out that the Sandinistas were likewise guilty of violence in the ongoing civil war.

Kirkpatrick’s defense of US actions quickly unraveled in October 1986 when a secret shipment of military supplied was shot down over Nicaragua. A captured crew member and documents on board revealed that these supplies were part of a regular covert operation by the CIA to supply the Contras in violation of US law. Even more damning was the subsequent publication of details about how the administration had used the profits from secret Iranian arms sales to supply the Contras. Three investigations conducted during the late 1980s and early 1990s made it clear that President Reagan was aware of the nefarious details of the weapons sales and secret funding of the Contras.

By the time the US public became aware of the basic details of the weapons sales in November 1986, many officials connected to the scandal had already resigned their posts. Reagan’s former National Security Advisor Robert McFarlane even attempted suicide, offering a vague apology to the American people in his note. Most officials were granted immunity for their testimonies, and those convicted of crimes were pardoned when Reagan’s vice president George H. W. BushFormer CIA director and vice president under Reagan, Bush would become the forty-first president of the United States after defeating Michael Dukakis in the 1988 presidential election. became president. CIA director William Casey passed away before the investigation, and Marine Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North shouldered much of the blame and was fired along with other midlevel officials whose convictions were later reversed or pardoned.

Reagan escaped impeachment by denying any knowledge of the weapons sales. In contrast to the workaholic Carter, who surrounded his office and bedroom with piles of documents, Reagan delegated most every decision to members of his administration. Outside of issues involving taxes, national defense, and the possible spread of Communism, Reagan seemed to regard most issues as details that were best handled by his staff. This orientation allowed Reagan to enjoy daily naps, frequent vacations, and a work schedule that rarely included evenings and weekends. Reagan’s critics charged him with being aloof and lazy. Others believed that the president’s chief advisor James Baker and a few others in Reagan’s inner circle were running the country rather than the man the American people had elected.

Ironically, years of criticism regarding Reagan’s hands-off management style helped to convince the American public that the Iran-Contra affair had been conducted in secret behind the president’s back. Reagan delivered a series of apparently heartfelt apologies along with a number of testimonies in which he responded, “I don’t recall” to nearly every question he was asked. For many Americans, the aging actor appeared as the victim of a partisan attack by individuals who hoped to further their own careers. Critics of the president maintained that even if Reagan was telling the truth, the fact that these criminal deeds were carried out at the highest levels of his administration was evidence that Reagan must step down. Others argued that President Reagan had knowingly funded an illegal war and sold weapons to terrorists.

The investigation effectively ended all aid for the Contras, who quickly agreed to a ceasefire. Once they were no longer engaged against the Contras, popular support for the Sandinistas also declined, and many Sandinista leaders were replaced by a coalition government following a 1990 election. However, the decade-long civil war had spread throughout Latin America and destroyed the region’s agricultural economy. This development helped to spur the growth of a number of powerful drug cartels. Because the Contras were also heavily funded by area drug smugglers and because the United States enlisted the services of notorious drug trafficker Manuel NoriegaThe head of Panama’s military, Manuel Noriega used his power to act as a dictator and controlled all aspects of the Panamanian government. Noriega had been a paid CIA contact for many years and was also paid by the CIA to funnel weapons and money to the Contras in Nicaragua. Noriega was also paid by numerous drug traffickers, which the United States ignored until 1988 when he was indicted for these crimes. After his refusal to recognize the legitimacy of the election of his political rival, US forces invaded Panama and arrested Noriega. to funnel money to the Contras, questions still remain about the complicity of the CIA in the resulting cocaine epidemic of the 1980s. Many residents of inner-city neighborhoods continue to blame the government for the introduction of “crack” cocaine, a highly addictive form of the drug that they believed helped to fund the Contras.