This is “The 1970s”, chapter 12 from the book United States History, Volume 2 (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 12 The 1970s

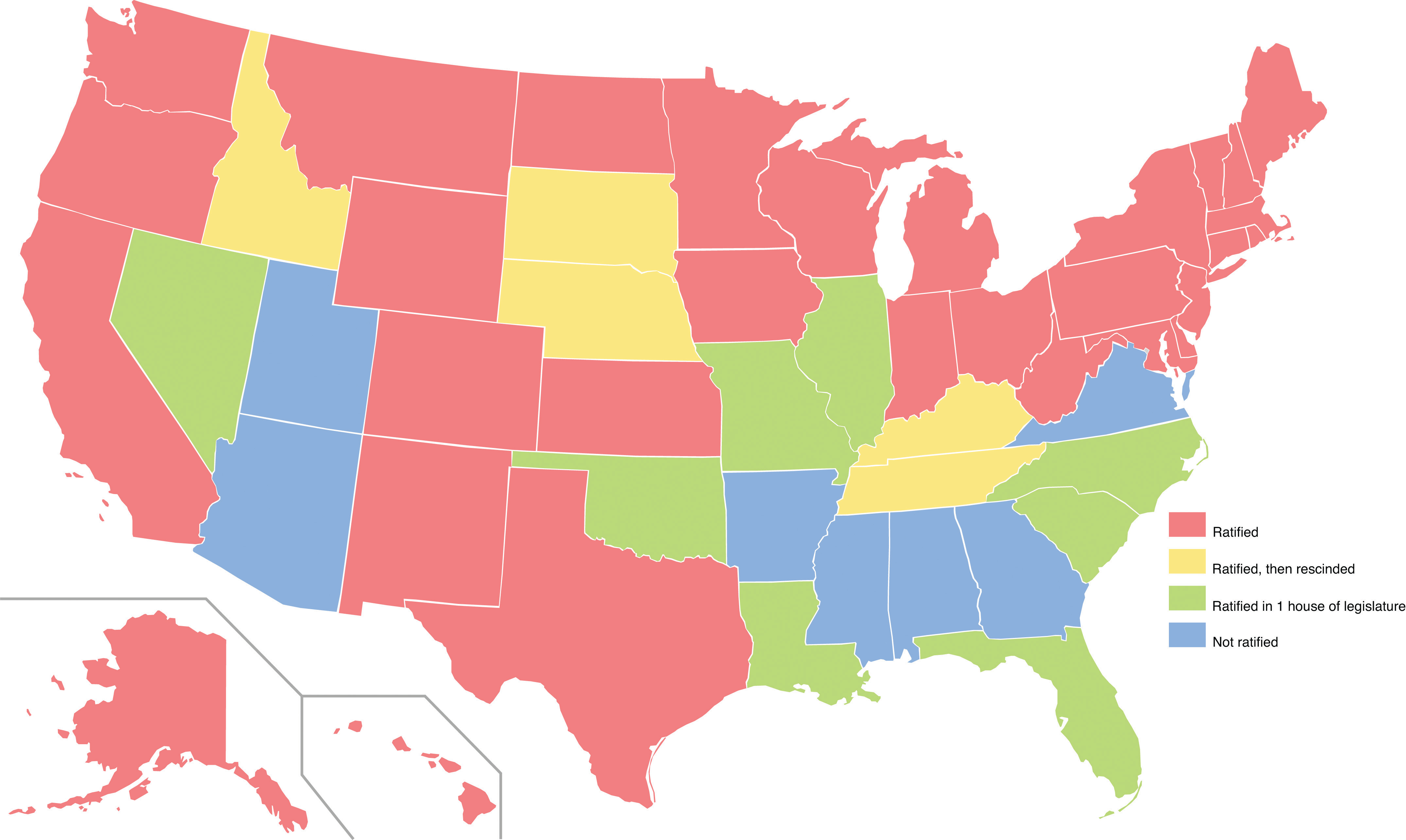

The most important achievement of the federal government during the 1960s was the belated achievement of the goals it had declared a century prior during Reconstruction. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 guaranteed equal protection irrespective of race, while the Voting Rights Act of 1965 protected the right of Americans to vote. The 1970s began with the last major expansion of that right, as Congress overwhelmingly approved a constitutional amendment extending suffrage to eighteen-year-olds in March 1971. The Twenty-Sixth Amendment was ratified by the states within a few months with virtually no opposition. Similar amendments had been offered in previous decades, but the 1960s demonstrated as had no other epoch in US history the political activism of college-aged students. It also demonstrated the sacrifice of the younger generation in Vietnam. As that war continued to rage, most Americans agreed someone old enough to be drafted into the military should also have a voice in government.

Despite liberal and conservative support for the amendment, the dominant feature of America in the 1970s continued to be partisan conflict. However, the 1970s were unique from the previous decade in two major ways. First, the most recognizable forms of racial and gender discrimination had been outlawed and a new federal agency had been created to enforce these laws. Most whites believed this was sufficient and hoped that issues of racial equality would cease to occupy a leading place in the public dialogue. Second, the nation experienced political, military, and economic crises at home and abroad that shook the confidence of most Americans.

Americans had grown accustomed to economic and military hegemony throughout the previous three decades. The political upheavals that challenged Soviet rule throughout Eastern Europe during the late 1960s and the rising tensions between China and the Soviet Union suggested that the United States was prevailing in the Cold War. However, the economic and military might of the United States failed to produce victory in Vietnam, insulate the nation from economic decline at home, or guarantee access to Middle Eastern oil. In response to each of these crises, liberals of the New LeftRefers to those who supported liberal causes during the 1960s and 1970s, such as civil rights for women and minorities and the expansion of the welfare state to confront problems faced by the poor. Whereas the “old” left embraced Socialism, the “new” liberal activists generally sought to distance themselves from Marxist ideas in favor of grassroots action within the existing political system. sought to reassure Americans that the promise of the 1960s might still prevail. Conservatives sought to reinvent themselves by distancing themselves from the racial intolerance of their past while seeking a return to the economic and political hegemony America had once enjoyed.

The New Left was a loose coalition of postwar liberal reformers labeled as “new” to distinguish themselves from the Socialist “old left” of previous generations. Conservatives had rallied behind Republican President Richard Nixon. Eisenhower’s former vice president issued a campaign promise to restore “Law and Order,” a slogan that appealed to many Americans who were uncomfortable with the rapid changes of the past decade. However, Nixon had also tried to win over moderates and promised to end the war in Vietnam shortly upon taking office. Nixon’s pledge of “peace with honor” was vague enough, however, that as president he could still claim that his escalation of the war was exactly what he had promised on the campaign trail.

Nixon hoped that increasing military aid for South Vietnam while escalating the aerial attacks on the rest of the country would allow him to slowly withdraw ground troops without surrendering any more territory to the North. Publicly, Nixon spoke of victory. Privately, even Nixon doubted that the North Vietnamese would ever abandon their campaign to reunite all of Vietnam. Absent of exit strategy, Nixon chose to escalate the war in the hopes of convincing the North to accept an armistice similar to the agreement that ended US participation in the Korean War. Success in this regard, Nixon believed, would make him the most revered commander in chief since Eisenhower. Instead, US forces would belatedly withdraw from Vietnam, which quickly succumbed to Communist forces. Following revelations about some of his secret dealings, Nixon would have the lowest approval rating of any US president and be forced to resign in disgrace.

12.1 Vietnam, Détente, and Watergate

Learning Objectives

- President Nixon claimed that antiwar protesters and public opinion about the war would not impact his policies regarding Vietnam. Describe those protests and the various opinions and perspectives about the war. Discuss how they likely did impact the president and the rest of the nation.

- Explain Nixon’s strategy regarding the war in Vietnam, and explain why a growing number of Americans opposed his policies. Summarize the process by which the war in Vietnam ended. Explain how the American withdrawal was accomplished and how it affected South Vietnam.

- Discuss the process by which the Nixon administration came to be involved in illegal operations, and explain how the Watergate break-in became linked to the president.

Escalation and Protest

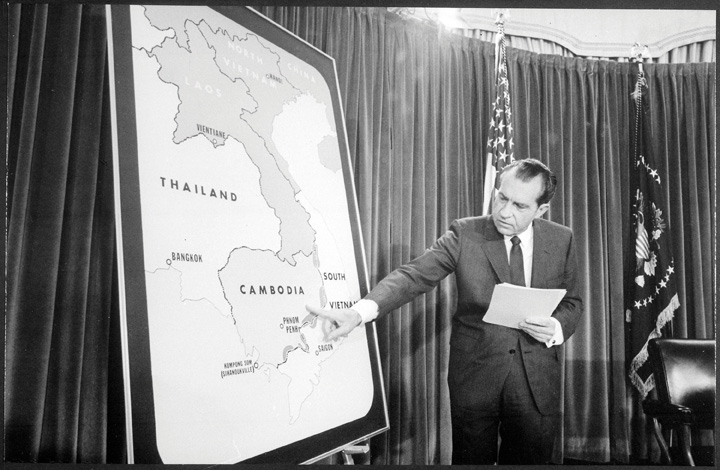

Figure 12.1

President Nixon points to Cambodia on a map during a press conference in April 1970. Although US forces had been conducting operations in Cambodia prior to this time, the announcement led to renewed protests by antiwar activists.

Almost immediately upon assuming office in early 1969, President Richard Nixon ordered the bombing of the independent and neutral nation of Cambodia. The president hoped to eliminate the supply network that linked North Vietnamese Army (NVA) with Vietcong (VC) fighters in the South. Although destroying these supply networks was a military necessity if the United States hoped to neutralize the VC, bombing a neutral nation violated a host of legal and ethical standards. As a result, the American people were not informed when military operations expanded beyond the Vietnamese border. The people of Cambodia and neighboring Laos had a different perspective, as 70,000 tons of bombs were dropped on their nations during the late 1960s.

In April 1970, Nixon announced that US ground troops would conduct small-scale missions in Cambodia. Antiwar protests increased in the wake of this announcement, and many Americans became concerned that the war might be expanding instead of moving toward the honorable peace Nixon had promised. In reality, Nixon was merely acknowledging what had already been occurring. The delayed protest demonstrates the almost willful complicity of the American media to pass on official military press releases and ignore reports from Laos and Cambodia. International media sources had reported on the bombing of Laos and Cambodia long before Nixon’s public announcement, yet only the New York Times and a handful of other newspapers in the United States reported the story. Most Americans wanted to know as little as possible about the Vietnam War—especially if it appeared that defeating the VC and North Vietnam required American troops to fight beyond the borders of Vietnam.

College students proved an exception to this rule as Nixon’s announcement was met with a wave of moral indignation. Hundreds of thousands of students participated in protests from Seattle Central Community College to the newly founded Florida International University in Miami. On May 4, 1970, a protest at Kent State University turned violent when Ohio National Guardsmen fired into a crowd and killed four students. The event polarized the nation, with those who still supported the war siding with the soldiers who had previously been attacked by rock-throwing students. Some of these students had even set fire to the Reserve Officer’s Training Corps (ROTC) building and then attacked firefighters sent to stop the blaze.

By one perspective, the Kent State tragedy was a “riot” that typified the lack of respect for authority and the rule of law. Those who opposed the war referred to the incident as a “massacre,” emphasizing that most of the students were peacefully exercising their constitutional rights of assembly and speech. Ten days later, Mississippi state police shot and killed two students and wounded a dozen others at Jackson State University, a historically black college. Area whites generally believed that the police used a judicious amount of force against the unarmed protesters, while African Americans considered the event to be another massacre. Like the students at Kent State, many had set small fires and were throwing rocks at the police. However, unlike the Kent State Riot/MassacreThe tragic death of four students on May 4, 1970, after an anti-Vietnam protest escalated into violence on May 4, 1970. Those who opposed the Vietnam War used the phrase “massacre” to describe the event and emphasized that the students were unarmed and exercising their right of free speech. Those who supported the war described the event as a “riot,” focusing on the arson and physical violence some of the students had used against the Ohio National Guard., which polarized the nation, the killings at Jackson State barely made headlines and are seldom included in the historical record.

Historical accounts of the home front also tend to underestimate the diversity of the antiwar movement that quickly expanded beyond activists and scholars like Noam Chomsky to embrace union leaders, Mexican American activists, white factory workers, conservative clergy, and veterans from both wealthy and humble origins Antiwar sentiment was strong in working-class neighborhoods as demonstrated by polls and antiwar protests. This was especially true in minority neighborhoods that provided a disproportionate share of the war’s casualties. Martin Luther King Jr. was one of the earliest national figures to publicly condemn the war. He was joined by other African Americans such as Muhammad AliAn outspoken heavyweight boxing champion who became a member of the Nation of Islam, Muhammad Ali was stripped of his title in the aftermath of his refusal to be inducted into the US Army after he was drafted. Perhaps the most famous athlete of his time, Ali based his refusal on his religious and political beliefs. After the military made it clear he would not see combat, Ali’s willingness to end his career and go to jail rather than accept an assignment traveling and entertaining troops challenged the image of cowardice that was associated with draft evaders. who was drafted but rejected the army’s offer to accept a cozy assignment entertaining troops. Refusing induction, the still-undefeated Ali was stripped of his title and was nearly sentenced to a long prison term.

Those who supported the war likewise represented a diverse cross-section of the United States. In fact, even the most liberal universities, such as Berkeley, were host to both antiwar protests and counterprotests by those who supported the war. Antiwar protesters who occupied campus buildings were usually surrounded by even more students who demanded that the protesters abandon their disruptive campaign so that classes could resume. This was especially true among anxious seniors who feared that the protests would disrupt their plans for graduation. Others publicized the atrocities committed by the North Vietnamese and Vietcong. For every Mai Lai Massacre, they argued, there was an instance of equal or greater inhumanity. After taking control of the city of Hue following the Tet Offensive, for example, Vietcong forces tortured and executed thousands of residents whom they believed had aided the United States.

In June 1971, former US Marine Daniel Ellsberg decided to leak a confidential study that detailed the history of escalation in Vietnam. Dubbed the Pentagon PapersA classified report on the US military’s actions in Vietnam between 1945 and 1967 that was created by the Department of Defense and leaked to the press by researcher Daniel Ellsberg. This report demonstrated that the military and Johnson administration had sought to mislead the American people regarding the success of their actions in Vietnam. by the media, the report contained 7,000 pages that revealed the long history of government misinformation dating back to the Kennedy administration. The New York Times and the Washington Post agreed to publish selections of the leaked documents until the Nixon administration temporarily blocked further publication of the leaked documents. The Supreme Court reviewed the Pentagon Papers and decided that the reports contained nothing that endangered national security, a decision that led to additional releases of the information they contained.

The American public was shocked at the candor of Ellsberg’s leaked documents. Each day the Times published a new letter from a different commander or military strategist plainly stating that the Vietnam War was unwinnable. The reports clearly indicated that the local population had no confidence in the South Vietnamese government and that no amount of napalm could convince them that this regime was fighting for their liberation. At best, these commanders believed that sending more troops and dropping more bombs might convince the enemy to negotiate a settlement that would preserve the image of American military power. The public was outraged to find how military and civilian leaders had deliberately falsified information to make it appear as though US forces were winning the war. Pentagon officials falsified the numbers of enemy killed, deleted all mention of civilian casualties, and buried information about the breakdown of military discipline among US troops.

Figure 12.2

As the war continued, an increasing number of Vietnam veterans returned home and contrasted their experiences with the Pentagon’s official reports of victories against Communist forces. Protests by veterans, such as this 1967 march, became more common in the final years of the war.

Pundits began using the phrase “credibility gapA phrase that came into common usage in the wake of scandals such as the release of the Pentagon Papers. The gap was the distance between what federal government officials knew to be true and the official statements of those officials.”—a term referring to the difference between what government officials reported about Vietnam and what the Pentagon Papers and other sources revealed the government actually knew to be the truth. The Pentagon Papers combined with previous revelations and the antiwar movement to convince most Americans that their president must direct his efforts to ending the war as quickly as possible. “Peace with honor” now meant withdrawal to a majority of Americans. Nixon responded by ending the draft and reducing the numbers of troops in Vietnam. The troop reductions and end of the draft greatly reduced antiwar activities, which led many to question whether peace activists were more concerned with preventing people like themselves from being sent to war rather than ending the war itself. Young men in need of employment continued to join the military and serve in Vietnam, while the rest of the nation pretended as if the war had ended along with the draft. Others pressed on, hoping to convince the nation that withdrawal from Vietnam was more honorable than maintaining the status quo to avoid the disgrace of surrender.

The Pentagon Papers covered only the years prior to Nixon’s election, yet the president became convinced that these documents were released by individuals who were bent on destroying his administration. As a result, Nixon began investigating members of his own staff rather than addressing the important questions that the Pentagon Papers raised about the US presence in Vietnam. Nixon directed his staff to use campaign funds to hire former CIA agents to spy on dozens of the government’s own employees. The administration dubbed these men “plumbers” in relation to their mission to investigate and prevent leaks of information that might harm the White House. Before long, these plumbing jobs expanded to a variety of illegal operations meant to spy on and discredit a long list of people the president considered to be his political enemies. One year almost to the day after the Pentagon Papers were leaked, a group of Nixon’s plumbers was caught inside the Democratic offices of the Watergate hotel.

Withdrawal and Fall of Saigon

The North Vietnamese launched another major offensive in the spring of 1972, but Nixon still hoped that he could force the North to accept a cease-fire under his terms. Although Nixon was one of the most knowledgeable US presidents when it came to foreign affairs, he was also one of the least likely to respect the limits of his own authority. While promising the American people that he was working toward peace, Nixon had secretly escalated the war. Nixon approved numerous bombing campaigns and ordered the navy to place mines in every major port of North Vietnam. At the same time, Nixon recognized that these efforts were unlikely to persuade the North to surrender. Nixon simply hoped these actions would help convince the North Vietnamese that US bombing campaigns might never cease, which might lead them to accept US demands regarding American withdrawal. The intense bombing likely had the opposite effect as negotiations stalled throughout 1972. The most contentious issue was the US demand that the North Vietnamese remove all forces from South Vietnam prior to US withdrawal—something that the North viewed as a potential trap.

As election of 1972 neared, over 60 percent of Americans called for an immediate end to the war. An estimated 50,000 to 100,000 draftees had refused to report for induction, many having fled to Canada. Over two hundred army officers had been killed by their own troops, and even veteran soldiers were refusing to follow orders in Vietnam. South Dakota senator George McGovernA historian who wrote about the labor strikes of the Colorado coalfields, George McGovern became a Progressive Democrat who represented his home state of South Dakota for over two decades. McGovern was defeated by Nixon in the presidential election of 1972, largely because he was viewed as too liberal while Nixon was viewed by many voters as a moderate. had called for an immediate end of the war in his failed attempt to win the Democratic nomination for president in 1968. His early opposition to the war gave him credibility among the left as he renewed his campaign for the 1972 nomination. His early opposition to the war was also his biggest political liability. To win the general election, the South Dakota senator needed to gain the support of Americans who opposed Nixon but also viewed the antiwar movement with suspicion.

McGovern was challenged by a number of leading Democrats, but the most intriguing aspect of the 1972 Democratic primary was the candidacy of Shirley ChisholmAn educator and community leader who entered New York politics and became the first African American woman elected to Congress in 1968. Four years later, she also became the first viable African American presidential candidate, winning several states in the 1972 Democratic primary.. An African American congresswoman from New York, Chisholm won several states of the Deep South that only four years prior had been carried by an archsegregationist. Chisholm never came close to challenging McGovern for the nomination, however, as the liberal South Dakotan also received the support of a diverse group of voters who desired change and an immediate end to the war. However, McGovern’s campaign promise to pardon draft evaders alienated many Americans. Recognizing that McGovern’s base of support was tied to Vietnam, Nixon maneuvered once again to promise peace while secretly escalating the war. Nixon withdrew his demand of North Vietnamese withdrawal from South Vietnam along with other provisions he knew would convince the North to agree to peace talks. These negotiations were held in private, allowing Nixon to declare that he had prevailed in forcing the North Vietnamese to accept US terms and delivered on the promise to bring “peace with honor.”

Figure 12.3

New York congresswoman Shirley Chisholm became the first black candidate to win a state primary in 1972. Chisholm won the Democratic primaries of New Jersey, Louisiana, and Mississippi, partly because many white Southerners had joined the Republican Party by this time. Her victory demonstrates the impact of the 1965 Voting Rights Act as these Southern states had excluded black voters and supported segregationist candidates in recent presidential elections.

Nixon’s announcement that peace talks were under way deprived McGovern of his leading issue and led to a second Nixon victory. Achieving peace in Vietnam would prove more difficult, and for Nixon, much less honorable. The latest in a long line of military leaders of South Vietnam pointed out what everyone already knew—North Vietnam would resume the offensive once US forces withdrew. The only hope of prevailing against the North absent of US ground forces, argued South Vietnamese leaders, was if US forces continued their bombing campaigns, provided increased military aid, and forced the North Vietnamese to withdraw from the areas of South Vietnam they presently controlled. Nixon understood that achieving all of these objectives was not likely given the political situation in his own country and the military situation in Vietnam. As a result, many view this first round of peace talks as an attempt to secure Nixon’s reelection and begin placing a positive spin on the abandonment of an ally the United States had created.

Ho Chi Minh had died in 1969, but his successors shared their former boss’s appreciation of the importance of American public opinion. As a result, they recognized that Nixon was under tremendous pressure at home to end the war. If they could simply survive the latest bombing campaign, they believed, Nixon would recognize that accepting North Vietnam’s terms for withdrawal was his only politically acceptable option. Once the election was over, however, Nixon brought back his original demand that the North abandon its positions in South Vietnam. He even demanded that the North abandon all efforts at reunification. The North refused these provisions once again, and Nixon responded by escalating the bombing of Southeast Asia.

On Nixon’s orders, US warplanes dropped 100,000 bombs in the last two weeks of December alone, pausing only for Christmas. Bombs once again proved poor agents of diplomacy. On January 27, 1973, Nixon returned to the bargaining table, this time accepting a cease-fire that permitted North Vietnam to keep the territory in South Vietnam it had already captured. Thousands of US troops and tens of thousands of Vietnamese died in the three months that Nixon had attempted to negotiate a more favorable end to the war. In the end, even Nixon understood that none of his demands were likely to prevent the North from resuming its offensive against South Vietnam as soon as US troops withdrew.

By April 1973, nearly all US forces had fled South Vietnam and the North launched a major offensive. South Vietnamese leaders made desperate appeals for assistance, but Congress and the American public made it clear that they would not accept any plan to redeploy troops to Southeast Asia. Nixon and his successor Gerald Ford sent military aid to South Vietnam and pleaded for Congress to reconsider. On April 30, 1975, the South Vietnam capital of Saigon was captured by North Vietnamese troops. American embassy staff in Saigon and the thousands of military and support staff that had remained in South Vietnam were airlifted to safety just as the troops entered the city.

Figure 12.4

The US military evacuated South Vietnamese officials and their families as Saigon was surrounded by Communist forces. Many of these civilians later migrated to the United States.

A war remembered for brutality ended with a demonstration of valor as US military and civilian officials risked their lives to rescue thousands of South Vietnamese officials during the airlift. Because of their support for US efforts, these individuals would have likely been imprisoned or even executed had they been captured by the North. Most were not fortunate enough to escape, and hundreds of thousands of South Vietnamese soldiers and officials were imprisoned. An estimated 1 million Vietnamese fled into neighboring Laos or Cambodia. Others commandeered any craft they could find regardless of seaworthiness and prayed they would be rescued by the US Navy. Tens of thousands of these civilians would eventually find asylum in the United States while the rest became refugees in a region that continued to be plagued by civil war.

Lessons and Legacies of Vietnam

Many US veterans also felt like refugees when they returned to a nation that was less than grateful for the sacrifices they had made or compassionate regarding the difficulty of adjusting to civilian life. Some 58,000 Americans lost their lives in Vietnam, while 365,000 suffered significant injuries. Not counted among this number were those who suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)An anxiety “disorder” that results after one experiences severe psychological trauma. Post-traumatic stress disorder was common among many American GIs during the Vietnam War, although few were diagnosed or treated by the Veterans Administration in a timely manner. Some believe that the use of the word disorder is inappropriate. These individuals argue that the psychological trauma experienced by many veterans is a normal reaction to psychological trauma.. The experience of Vietnam veterans, like those of all wars, varied greatly. Infantrymen deployed to forward locations were surrounded by death, and some turned to alcohol and illicit drugs. For some troops stationed in bases throughout the region, the greatest battle was against tedium. When these men returned to the States, many felt that they were ostracized and reverted to their old addictions. Most others simply tried to rebuild their lives, demonstrating a resiliency that was as inspiring as their many selfless actions in combat.

Refugees in Southeast Asia likewise suffered from the lingering scars of war, as well as new ones caused by land mines that remained buried throughout the region and that killed thousands of civilians each year. The war also resulted in the destabilization of neighboring countries. Cambodia descended into civil war. The Communist Khmer RougeFollowers of the Communist Party of Cambodia who seized power following a civil war that coincided with the war in neighboring Vietnam. Led by the brutal dictator Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge executed between 1 and 2 million people in their effort to purge Cambodia of skilled workers, the educated, and any other person they deemed subversive to their vision of a totally agrarian society. under dictator Pol Pot eventually seized power and executed an estimated 2 million Cambodians in the late 1970s. Thanks to the efforts of civil rights veteran Bayard Rustin and countless other activists who publicized the conditions Cambodians faced, tens of thousands of Cambodian and Vietnamese refugees were granted sanctuary in the United States.

Americans differed in their interpretations regarding the outcome of the war. For some, like General William Childs Westmoreland, the war had been lost on the home front where protesters had sapped the will of civilian leaders. For others, the war was based on false assumptions, and protests were needed to call attention to the incongruities and inhumanity that surrounded its execution. Controversy regarding the Vietnam War carries into the classroom where students are more likely to learn about massacres than battles. In sharp contrast to the campaign maps that are presented for previous wars, there is rarely any discussion of tactics and strategy or even a single battle beyond the Tet Offensive. The historic view of the home front during Vietnam is also unique. Students learn about protesters rather than factory production, leaked internal documents take the place of encryption machines, and the returning GI appears as a shadowy figure implicitly juxtaposed against the “Greatest Generation” that saved the world from Hitler.

Recollections of Vietnam veterans reveal both the rationale and the shortcomings of this unique historical memory regarding the military history of the war. Oral histories reveal alienation and despair, the inhuman nature of guerilla warfare, and numerous atrocities committed in the name of survival. They also reveal the valor of American GIs who resolved to never leave a fellow soldier behind against a hidden enemy. Interviews with NVA and VC troops indicate a sort of bewildered respect for the dedication of American GIs toward their brothers in arms, questioning the logic of sending entire platoons to rescue a wounded soldier. Opposing forces were especially mystified that US soldiers would even risk their lives to retrieve the body of their fallen comrades. From the perspective of the GI, however, defending the life and memory of a trusted friend may have been the only part of their service that truly made sense to them. However, American veterans returned to a public that was disinterested in their experiences. After four decades, few historians have sought to collect and preserve these perspectives.

Figure 12.5

American soldiers refuse to leave wounded and deceased comrades on the battlefield, a practice that has led to both respect and bewilderment among adversaries. Although risking one’s life to bring home the remains of another comrade makes little sense to many outsiders, it is one of the defining characteristics of a US soldier.

The historical memory of Vietnam is also unique when it comes to the legacy and lessons of the war. Some Americans believe that the lesson of Vietnam is the danger of granting military leaders too much power and the reluctance of civilian officials to respond to popular pressure to end the war. For others, the message for future generations is the danger of permitting politics and politicians from withholding the full range of resources and options from commanders in the field. By this perspective, the overwhelming advantages of the United States in terms of resources and technology made US victory inevitable had it not been for limits placed on military commanders. These individuals believe the United States could have surrounded and eliminated all who opposed their will if only permitted to wage total war as they had in World War II. From the perspective of many Vietnamese, however, the use of napalm and bombing campaigns that dropped a total of five hundred pounds of explosives per resident of Vietnam more closely defined “total war” than any conflict in world history.

Many in Congress at least tacitly agreed with the antiwar perspective and approved the War Powers ActA law designed to limit the ability of the president to commit US troops without the authorization of Congress in the wake of the Vietnam War. The law permits the president to send troops without congressional approval in cases of national emergency. However, she or he must notify Congress within forty-eight hours of this action and withdraw US forces within certain time limits without congressional authorization or a declaration of war. over Nixon’s veto in November 1973. The new law required the president to notify Congress of any troop deployment within forty-eight hours. It also prohibited the president from using troops in an overseas conflict beyond sixty days without a congressional declaration of war. Those who had protested the Vietnam War celebrated the decision as a vindication of the Constitution and proof of the eventual triumph of democracy. Others argued that the new law permitted the fall of Saigon and doomed many Vietnamese who had supported the United States. Still others feared that the reluctance of the United States to intervene militarily might embolden America’s enemies. By this perspective, the War Powers Act aided Communist forces in neighboring Cambodia and discouraged those who were fighting against a left-leaning faction in Angola during subsequent years. For advocates of containment, the legacy of Vietnam was one of second-guessing military commanders and an emasculation of America’s commitment to supporting anti-Communist forces around the globe. For others, Vietnam was a reckless intervention that escalated local conflicts and paved the way for the kind of totalitarian regimes that developed in places like Angola and Cambodia.

Watergate

Nixon had long believed that his political enemies were conspiring against him ever since losing back-to-back elections, first for the presidency in 1960 and then for the governorship of California in 1962. As president, the release of the Pentagon Papers convinced Nixon that enemies inside his own administration were working against him. In response, he hired former CIA and FBI agents to spy on dozens of his own officials in search of “disloyal” employees who might be leaking negative information to the media. Dubbed the “White House Plumbers,” these covert operatives illegally tapped phones and eventually expanded their operations to include breaking into the offices of political rivals.

On June 17, 1972, five of the plumbers were caught inside the offices of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) headquarters in the Watergate complex in Washington, DC. The Watergate break-inA burglary of the Democratic headquarters committed by the supporters of Republican President Richard Nixon in June 1972. Nixon was forced to resign the presidency due to his efforts to cover up the crime. had been authorized by the Committee to Reelect the President (often referred to by the inaccurate but perhaps fitting acronym CREEP). The break-in was conducted with the knowledge of Nixon’s attorney general John Mitchell, chief of staff H. R. Haldeman, and chief domestic advisor John Ehrlichman. Most importantly, it had been approved by Nixon himself. Watergate was one of dozens of illegal operations designed to neutralize Nixon’s potential opponents. In fact, the June 17 break-in was not the first time Nixon’s supporters had targeted the DNC headquarters, and this particular operation was needed to fix the phone taps that were improperly placed in a previous break-in.

Figure 12.6

Among the evidence used against the White House Plumbers were hidden microphones placed inside ChapStick containers.

Given Nixon’s overwhelming victory over Democratic candidate George McGovern, who won only 17 votes in the Electoral College to Nixon’s 520, few suspected that Nixon or any of his top advisers would have ordered the break-in. Given the amateurish methods of the burglars, most Americans assumed Watergate was the effort of some politically motivated fringe group. Secretly, however, Nixon and his top assistants had moved into damage control mode and diverted tens of thousands of dollars in campaign funds to be used as bribes to convince the five arrested men from revealing their connections to the Committee to Reelect the President. These efforts might have succeeded as the prosecutors and press displayed little interest in the initial trial of the five burglars in January 1973. The most piercing questions actually came from the judge. In response, one of the burglars revealed some of what he knew about the conspiracy. This individual was James McCord, a former CIA operative who resented the way the Nixon administration had tried to blame the CIA for a number of unrelated mistakes. Ironically, Nixon would later try to use the CIA to derail the investigation.

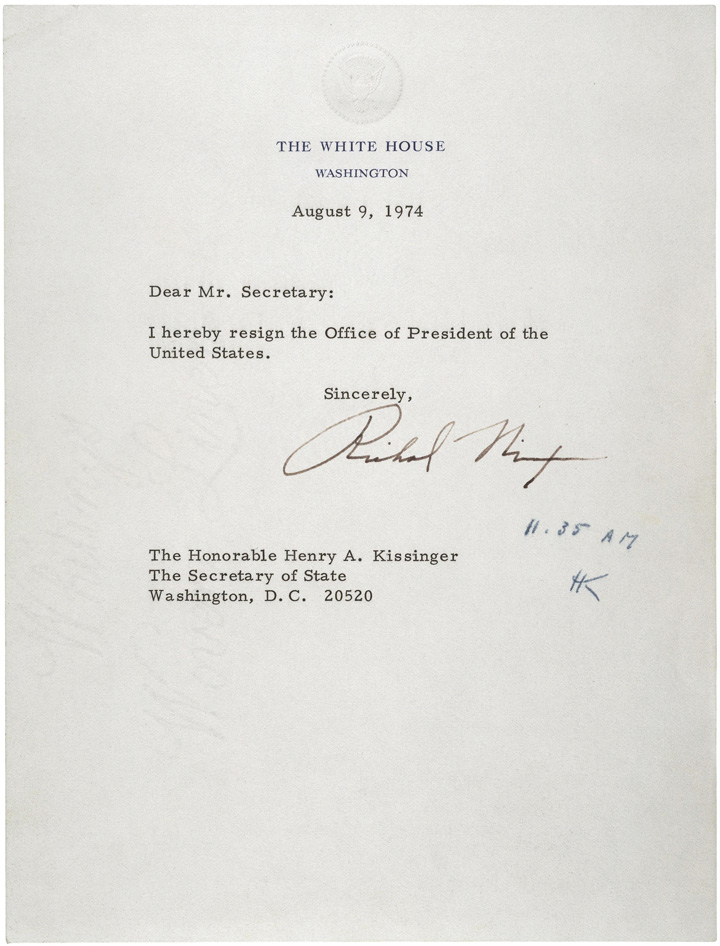

Figure 12.7

Nixon’s letter of resignation included no statement of guilt or innocence regarding his affiliation with the Watergate Break-In. Nixon was pardoned by President Ford and continued to maintain that he had only acted in the best interests of the nation.

By the spring of 1973, Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein were chronicling numerous connections between the Watergate break-in and Nixon’s most trusted advisers. As they closed in on the truth, Nixon hoped to find someone in his coterie, preferably someone at the lowest level, to admit that he or she had ordered the break-in without consulting the president. There was little honor among thieves and even less among the Watergate burglars. By this point, these men had already been given a combined $75,000 from Nixon’s campaign fund to keep quiet. Nixon found that none of his top advisers were willing to fall on their swords to protect him at any price. Many of these men had been conducting illegal or quasi-legal operations for several years, each believing they had enough evidence of the other’s dirty tricks that none of the president’s men would dare testify against the others. However, due to relentless investigating and the testimony of a few officials outside Nixon’s coterie, enough information became known to force the resignation of many of Nixon’s top officials by April 1973.

These resignations and the acting FBI director’s admission that he had destroyed evidence related to the Watergate break-in led to a high-profile senate investigation in the summer of 1973. One individual testified that the president had known about the break-in and ordered a cover-up. Still others presented the break-in as an operation conducted by people who supported Nixon but were operating without the president’s knowledge. It looked to most Americans that Nixon had some connection to the Watergate break-in, but there was still no firm evidence either way until it was discovered that the president had installed a taping system that recorded every conversation in the Oval Office.

Nixon had installed the system believing that only he would have access to the secretly recorded conversations, a resource that could be used to blackmail potential rivals as well as record the events of his administration for his memoirs. Ironically, public knowledge of the tapes proved Nixon’s undoing. Nixon tried to stay ahead of events by voluntarily turning over a few tapes that he believed would prove his innocence. However, these tapes had obviously been tampered with. As a result, this led to increased demands that all of the tapes be turned over. Nixon refused, however, citing executive privilege because of the many sensitive conversations that occurred in the White House on various matters unconnected to the Watergate investigation. Nixon also ordered his attorney general to fire the special investigator who had requested the tapes. Instead, both the attorney general and the assistant attorney general resigned in protest.

If Nixon was not guilty of collusion or a cover-up, the American public asked, why was he working so hard to derail the investigation? Nixon’s public approval fell to 24 percent—the lowest of any president in US history. As Nixon continued to insist that he was “not a crook,” the nation endured an agonizing year of trials and procedural investigations. The investigations culminated with the US Supreme Court case United States v. Richard M. Nixon, after which Nixon was ordered to release the White House tapes. Anything dealing with matters of national security remained classified, but the president’s conversations regarding Watergate were released. These tapes indicated that Nixon had conspired to use the CIA to cover up the Watergate break-in. These illegal actions were the reason Nixon was impeached and would have been removed from office had he not voluntarily resigned on August 8, 1974. However, the tapes were most shocking in their revelation of secret operations in Cambodia and dozens of illegal spying operations beyond Watergate.

Resignation and Aftermath

Nixon’s resignation would have elevated Vice President Spiro Agnew to the presidency had he not previously been forced to resign after an unrelated investigation revealed the former Maryland governor had accepted bribes from a government contractor. Agnew resigned in October 1973—just as the Watergate investigation was heating up. Nixon appointed Michigan congressman Gerald FordThe thirty-eighth president of the United States, Gerald Ford had been a long-serving member of Congress representing Grand Rapids, Michigan. Ford was appointed by Nixon to replace Vice President Spiro Agnew after he was forced to resign following a finance scandal. Nixon soon resigned as well due to his role in Watergate, which elevated Ford to the presidency. to replace Agnew. As a result, it was the unelected Gerald Ford who became president when Nixon resigned.

As president, Ford disarmed many critics through candor and humility. Ford was the first to point out that he had been appointed rather than elected and promised to lead by consulting others. He also joked that he was a “Ford not a Lincoln,” a humble remark and a reference to the reliable and no-frills line of automobiles he implicitly contrasted against the luxury models offered by the same company. He could have called himself a Mercedes, as most Americans were simply relieved that the long national nightmare of Vietnam and Watergate was over. Ford’s approval rating stood over 70 percent when he took office. However, the new president may have confused the public’s desire to move forward with a willingness to forget all about Watergate. Ford’s approval rating dropped 20 percentage points the day he announced a full pardon of ex-President Nixon for any crimes he committed—including ones that might be found in the future. Many Americans believed that Ford was now part of the Watergate cover-up, speculating that he had been appointed in exchange for a promise to pardon Nixon if he was forced to resign.

The Watergate investigation revealed that the CIA had participated in many of Nixon’s surveillance operations and had conducted wiretaps and other illegal investigations of antiwar organizations inside the United States. The agency came under fire as the CIA was prohibited from conducting domestic operations. The result was a series of investigations that revealed a litany of CIA assassination plots, secret payments, and even an effort to destabilize Cuba by poisoning livestock in hopes of fomenting revolt against Castro.

It also became clear that the CIA had supported a military coup that led to the death of Chile’s elected leader Salvador Allende in September 1973. Allende was a Marxist who the CIA had tried to prevent from being elected in 1970. Once in office, the CIA worked to disrupt Allende’s government and recruited Chilean officials who might be interested in using the military to seize power. The US government’s exact role in supporting the coup has never been precisely determined, but the Nixon administration welcomed the emergence of coup leader Augusto PinochetDictator who ruled Chile after leading a coup against the democratically elected Socialist leader of Chile in 1973. Fearing the spread of Socialism in South America, the United States offered tentative support for Augusto Pinochet’s regime despite his brutal repression of dissenters. as a victory against Communism. Pinochet tortured and executed thousands of Allende’s supporters and replaced a left-leaning but democratically elected government with one of the most repressive military dictatorships in Latin America. Once this information became public, Congress decided to curtail the CIA’s power to operate with impunity and passed laws demanding closer scrutiny of future operations.

Review and Critical Thinking

- What did Nixon mean by “peace with honor?” Were his actions as president consistent with this campaign promise? If not, what other options did he have regarding the Vietnam War?

- How could a candidate such as George McGovern fare so poorly in the general election of 1972, even among those who desired an immediate end to the Vietnam War? Why was Nixon able to present himself as a moderate?

- How could over two years elapse between the Watergate burglary and the impeachment trial and resignation of President Nixon? Was there any way that Nixon might have prevented the public from discovering his role in the break-in? What would have occurred if Nixon had immediately admitted that there was a connection between his supporters and the break-in?

- Given his tremendous lead in the polls, few suspected Nixon was behind the Watergate break-in. What led Nixon to approve operations that violated the law? How did his willingness to conduct these kinds of operations outside the law affect his presidency? Why might an American public that expects and even supports the use of these techniques by US intelligence forces abroad react with such indignation to Nixon’s use of domestic surveillance?

- How did Vietnam and Watergate change America?

12.2 Détente, Decline, and Domestic Politics

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the connections between the energy crisis and US foreign policy in the Middle East. Analyze the influence of the Cold War on America’s actions in the Middle East during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Also, consider the importance of domestic economic and strategic policy concerns as they influenced Middle Eastern affairs at this time.

- Summarize Nixon’s foreign policy regarding the Soviet Union and China. Explain why a cold warrior such as Nixon would decide to simultaneously reach out to China and the Soviet Union during an era in which the relationship between these nations had declined.

- Summarize the key issues and events surrounding leading domestic issues, such as the economy, environment, welfare, and abortion/reproductive rights in the early 1970s. Present various perspectives on each of these controversial issues in a way that demonstrates an understanding of the way various Americans interpreted each.

The Energy Crisis

In the 1960s, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)A cooperative formed in 1960 by oil-exporting nations whose members seek ways to maximize profits related to oil exports. OPEC demonstrated its power in the 1970s with a series of boycotts against the West that led to a severe energy crisis and increased price for oil. Most OPEC members are located in the Middle East, but other members include Venezuela, Angola, Nigeria, and Ecuador. was created as an economic alliance that hoped to work collectively to regulate the global oil market. Oil-producing nations such as Venezuela, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia believed that the tremendous postwar demand for oil did not match its price, which had remained fairly constant in real dollars for nearly a century. However, OPEC’s initial efforts to restrict production stumbled because these nations were so dependent on oil exports for their livelihood—the very factor that had kept supplies high and prices low. The only way to increase the price of oil, OPEC founders recognized, was to reverse the present power structure and make nations that imported oil dependent on the nations that produced oil, rather than the other way around. The challenge was to convince all oil-exporting nations, especially those of the predominantly Arabic Middle East, to restrict production simultaneously.

A failed invasion of Israel by several of oil-producing nations in 1973 spurred the unity OPEC leaders had been hoping for. In response to the West’s support of Israel in the Yom Kippur WarOctober 1973 invasion by Egypt and Syria of the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights along their disputed border with Israel. These territories were formerly held by Egypt and Syria, but had been occupied by Israel after Israel repelled a similar invasion in 1967. With Western aid, Israel once again defeated Egypt and Syria., OPEC’s Arabic member states voted to impose an embargo on the United States and Western Europe in October. The war itself was a continuation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, as Egypt and Syria reinvaded Israel in hopes of taking back territory it had lost in previous wars. The United States and Western Europe responded with military aid that assisted Israel in its successful defense. This Western intervention resulted in a coordinated effort by religious and secular leaders throughout the Arabic world to force the West to abandon Israel, with the method being the refusal to sell oil to any ally of Israel.

The embargo was not simply about ethnic and religious conflict. For many years, the members of OPEC and even the US-installed shah of Iran had complained that Western nations charged inflated prices for the food and manufactured goods they exported to the Middle East while the oil they purchased remained constant despite growing demand. These complaints were especially relevant in 1973 given recent inflation. The price of Western goods had doubled even as the price the West paid for oil remained about the same.

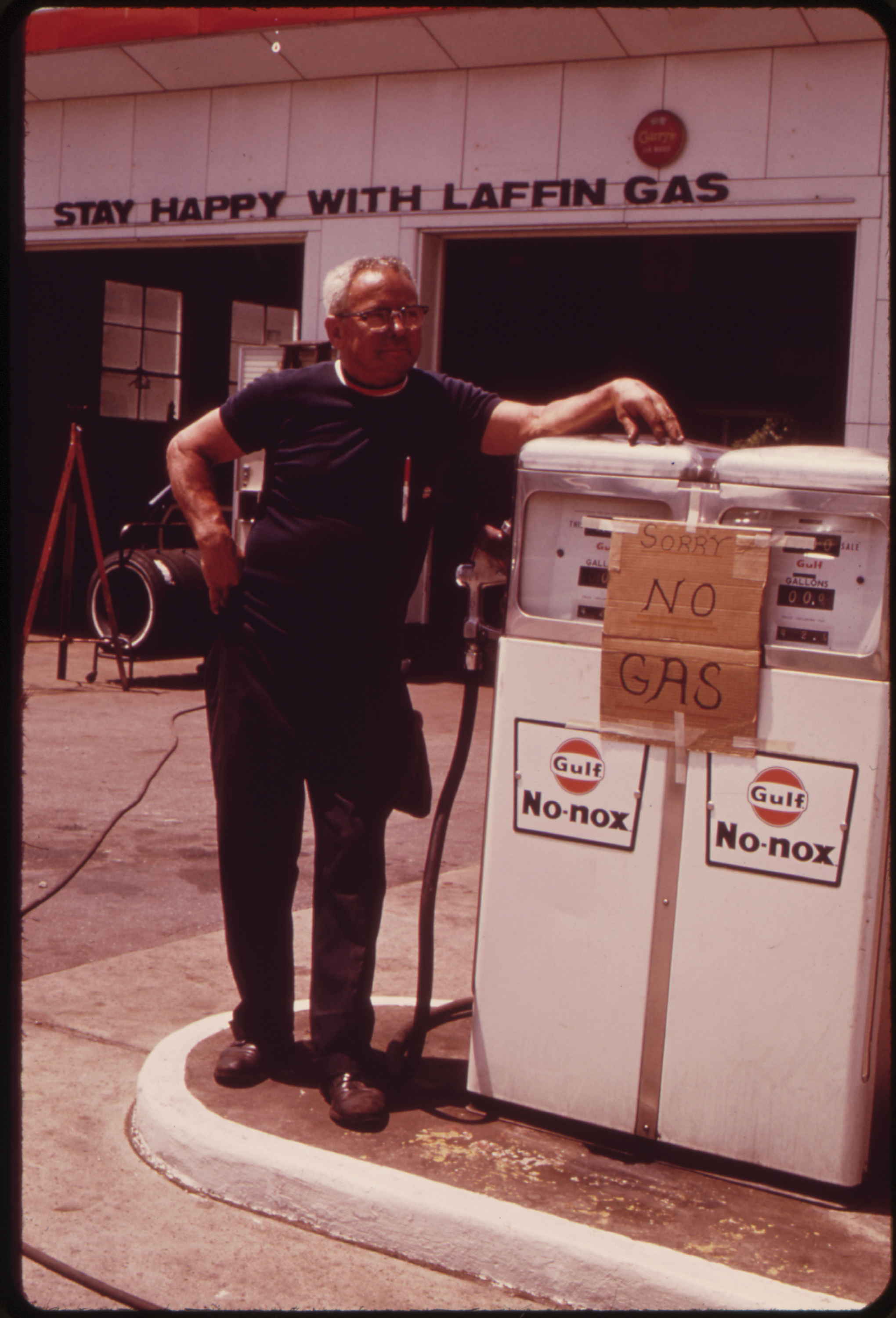

In the first two decades after World War II, Americans had grown accustomed to the idea that their nation dictated the economic, political, and military terms that other nations (outside of the Soviet sphere) abided by. The oil embargo challenged this confidence and caused an energy crisis that affected all Americans instantly. Fuel prices quadrupled after the start of the embargo in October 1973. An estimated one in five gas stations simply ran out of fuel altogether during the peak of the crisis the following spring. Recognizing that the gulf between supply and demand was so great that the price might continue its upward spiral, the government limited the amount of oil each state received and began printing fuel ration coupons similar to those used in World War II. Although the embargo ended before the federal rationing program took effect, states passed regulations limiting the number of days consumers could purchase fuel. For example, many states utilized a system where a digit in a consumer’s license plate determined what days they could purchase gasoline. Speed limits were reduced to fifty-five miles per hour or less, and even NASCAR reduced the distance of its races to conserve fuel.

Figure 12.8

Thousands of service stations simply ran out of fuel during the 1973 energy crisis, including this cleverly named service station.

The US economy was damaged but not disabled by the embargo because domestic oil production still accounted for 70 percent of the nation’s consumption in the early 1970s. In addition, domestic production quickly increased once price controls were released, permitting US oil companies to sell their product at market prices, which were substantially higher than the rate the government had set. However, many Western European nations depended almost entirely on the Middle East for oil. North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) members were beginning to reconsider their relationship to Israel, demonstrating the limits of US authority over its own NATO allies. In response, the United States offered millions in aid payments to Israel in exchange for an agreement to withdraw from several areas that were claimed by its Arabic neighbors.

From the perspective of these Arabic nations, the embargo demonstrated that oil could be used to further political objectives. However, business and political leaders in Saudi Arabia and other nations were more impressed by the rapid increase in the price of oil. Saudi Arabia decided to resume sales to the West in the spring of 1974 to take advantage of the dramatic price increase. Other Arab nations likewise placed profits ahead of politics, easing the embargo on nations that still supported Israel. However, the price of oil remained near its 1973 highs because OPEC successfully restricted production and maintained the artificially high price after the initial embargo. Oil did not return to its pre-1973 price (adjusted for inflation) until the 1980s and 1990s when global production increased and the end of the Cold War promoted freer trade. During these later decades, OPEC struggled to dictate production quotas to its members, several of which were at war with one another and in desperate need of revenue.

The Cold War and Détente

Even as America dropped bombs on Communist-controlled areas of Southeast Asia, the Nixon administration was able to almost simultaneously reduce tensions with the Soviet Union and China. Critics of the Vietnam War questioned how the same government that had justified escalation in Vietnam as necessary to roll back Chinese and Soviet aggression could negotiate so freely with both nations while simultaneously requesting more military aid for South Vietnam. From the perspective of the Nixon administration, however, the increased tension between the Soviet Union and China presented an opportunity to drive a wedge in the heart of the Communist world. Others simply hoped diplomacy might be a step toward peaceful coexistence.

The same optimism did not extend to the Middle East, where Cold War tensions and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict mixed with concerns about the flow of oil and control of the Suez Canal. Cold War tensions also continued to intensify local conflicts in Central Asia, Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia. In each of these areas, the Cold War expanded postcolonial conflicts into full-scale wars fought by local people armed with US and Soviet weapons. Given the consequences of US escalation in Vietnam, these conflicts remained peripheral to Nixon’s diplomatic strategy of détenteThe lessening of tensions between adversaries. In this context, détente refers to a reduction of tensions among political leaders and nations. (lessening tensions) with the Soviet Union and China. During his five-and-a-half years in office, Nixon negotiated the most significant arms reduction treaty in world history to that time, restored diplomatic relations with China, and discovered common ground with Soviet leaders based on mutual self-interest and maintenance of the status quo.

The Nixon administration’s greatest application of détente was the reestablishment of diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China. Nixon’s visit to China was cloaked in secrecy, the culmination of covert meetings arranged by National Security Adviser and future Secretary of State Henry KissingerA political scientist who served as Nixon’s national security adviser and secretary of state for both the Nixon and Ford administrations. He is best remembered as an advocate of détente between the United States and the Soviet Union and China.. Kissinger recognized that if the United States could normalize relations with China, it could further isolate the Soviet Union in world politics. The public’s first clue that the two nations might resume diplomatic relations came in the spring of 1971 when China invited the US ping-pong team to Peking. Even this seemingly nonpolitical invitation was part of the secret communications between China and the State Department.

In February 1972, Nixon surprised the world with his unannounced arrival in Peking. Nixon and Mao met and agreed to resume diplomatic relations and work toward mutual trade agreements. Nixon also agreed to withdraw US forces from Taiwan, the non-Communist Chinese government in exile that America had recognized as the legitimate government of China for the past two decades. To the rest of the world, it must have seemed peculiar to witness the former cold warrior, who frequently warned Americans about the dangers of “Red China,” shake hands with Chairman Mao. Others were more amazed that conservatives in America raised few objections to Nixon’s withdrawal of US forces from anti-Communist Taiwan. But the rapprochement was not necessarily atypical for the pragmatic Nixon or the contrarian nature of Cold War politics. Just as only Eisenhower could have questioned military spending in the midst of the Cold War, Nixon may have been the only politician who could have made such a move without being labeled as “soft” on Communism.

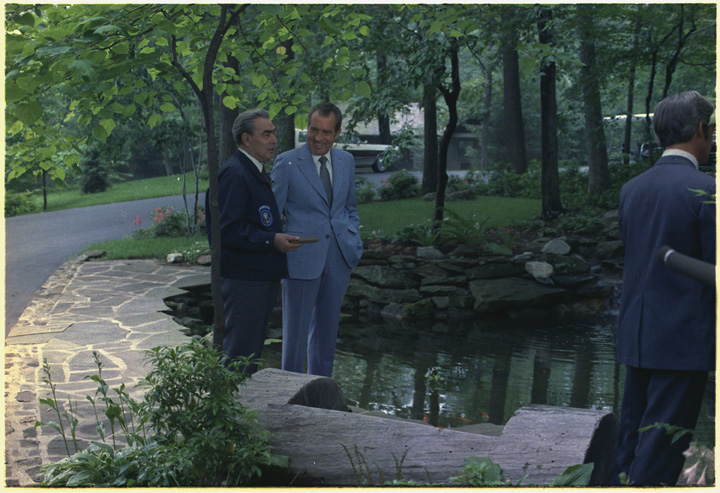

Resumption of diplomatic relations with China increased pressure on the Soviet Union to tread carefully as the United States and China moved closer to one another. In fact, one of the leading reasons Nixon visited China was to further détente with the Soviet Union on his terms. Nixon and Soviet premiere Leonid BrezhnevThe leader of the Soviet Union between 1964 and 1982, Brezhnev greatly increased the power of the Soviet military but also sought to reduce tensions with the West he recognized were hurting his nation economically. Brezhnev notoriously crushed democratic movements in Eastern Europe and invaded Afghanistan under a premise known as the Brezhnev Doctrine that justified intervention if the interests of area Communist nations were endangered by the internal affairs of another nation. communicated frequently, and both agreed that some forms of Cold War competition, such as infinite nuclear proliferation, were mutually self-destructive. Détente was generally welcomed by both sides and is typically praised by historians; but it was not without its own internal contradictions. Détente was predicated on the acceptance of “mutually assured destruction” as a key to stability—a sort of nonviolent hostage taking that discouraged aggression on all sides. Détente also meant that both sides accepted the postwar division of Europe and much of the rest of the globe.

Détente’s emphasis on stability appealed to and angered many Americans at the same time. The left was optimistic that détente would lead to arms reductions but was careful to point out that stability did not imply justice for the people of the world struggling under Soviet domination. Those on the political right likewise viewed détente with uncertainty. For conservatives, détente was a tactical victory that also might signal a retreat from earlier commitments to wipe Communism from the map. In contrast to the moral certainties and rhetoric of cold warriors like Nixon in the 1950s, détente also meant the abandonment of clear-cut interpretations of nearly every global and domestic event as related to Communist aggression.

Figure 12.9

Richard Nixon meets with China’s Mao Tse-tung in February 1972.

The apex of détente during the Nixon administration occurred in 1972 when the United States and Soviet Union signed the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT)Because there were actually two SALT treaties, the 1972 treaty between the United States and Soviet Union that froze the number of nuclear missiles each nation could possess is called SALT I. A treaty in 1979 that sought to build on the arms reductions of SALT I is called SALT II, although the second treaty was never approved by Congress.. The SALT treaty was the culmination of years of negotiations and limited the number and type of nuclear missiles each nation could possess. The Moscow Summit also featured a series of agreements that encouraged trade and cooperation between the two nations. Each of these agreements was soon jeopardized by internal affairs within the Soviet Union and the American response to these changes.

Concerned with the growing number of wealthy and talented people who were leaving the Soviet Union, Moscow added a large monetary fee for visas that prevented most of its citizens who wished to leave the Soviet Union from doing so. Liberals in Congress blasted the provision as a violation of the civil rights of Soviet citizens while conservatives utilized the provision to renew their anti-Soviet rhetoric. Congress responded by passing a law that denied favorable trade relations with any non-Capitalist nation that restricted the movement of its own citizens. Although it did not mention names, the provision was clearly aimed at the Soviet Union. The new law angered Soviet leaders, even those who opposed the emigration restrictions they had just passed as a tacit admission that their nation had yet to become the worker’s paradise Karl Marx had predicted. The Nixon administration recognized that pushing for internal Soviet reform would torpedo his efforts at détente and tried to get Congress to reverse course. Ironically, the mines and bombs Nixon had previously ordered against North Vietnam torpedoed his attempts at détente when one of these mines sunk a Soviet ship and caused the deaths of many sailors.

Figure 12.10

Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev meets with Richard Nixon in June 1973.

Despite increased tensions following this naval tragedy, Nixon and his successor Gerald Ford attempted to keep improving relations between the United States and the Soviet Union. Other than an increase in trade (mostly American grain desperately needed by the Soviet people), détente had peaked in 1972. Ford retained Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, but even the efforts of this brilliant diplomatic tactician failed. A notable exception occurred in August 1975 when both Ford and Brezhnev joined thirty-three other nations in signing the Helsinki AccordsA 1975 treaty signed in Finland intended to reduce Cold War tensions. The United States, Soviet Union, and other nations that signed the treaty agreed to accept the post–World War II division of Europe, including a promise to respect the present borders of nations in Europe. The agreement also committed each nation to honor the UN Declaration of Human Rights.. Signatories of this declaration agreed to respect the present national boundaries throughout Europe. The agreement effectively meant that the United States, the Soviet Union, and the other nations accepted the postwar division of Europe into eastern and western spheres and agreed to respect existing national borders.

The agreement also contained a pact to abide by the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights that Eleanor Roosevelt had pioneered. This final provision worried the authoritarian leaders of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe who continued to arrest their own citizens for political dissent. In 1970s America, where dissent was often celebrated, Gerald Ford came under fire from both the left and the right for his participation at Helsinki. Liberals viewed the declaration as an abandonment of those in Eastern Europe who were fighting for democracy and therefore challenging the postwar division of Europe. Conservatives agreed, although they focused their anti-Helsinki rhetoric on what they believed had been another episode of Americans kowtowing to Soviet and other world leaders.

Cities and the Environment

Many Americans viewed recent world events, especially America’s military defeat in Vietnam and its growing dependency on foreign oil, as a symptom of the economic decline that affected their daily lives. Thousands of factories closed each year and the relative wages of industrial workers declined throughout the 1970s. So many Americans migrated in search of work between 1970 and 1990 that the majority of the nation’s population growth occurred in the South and the Southwest. By 1980, more Americans lived in these Sunbelt regions than the rest of the nation combined.

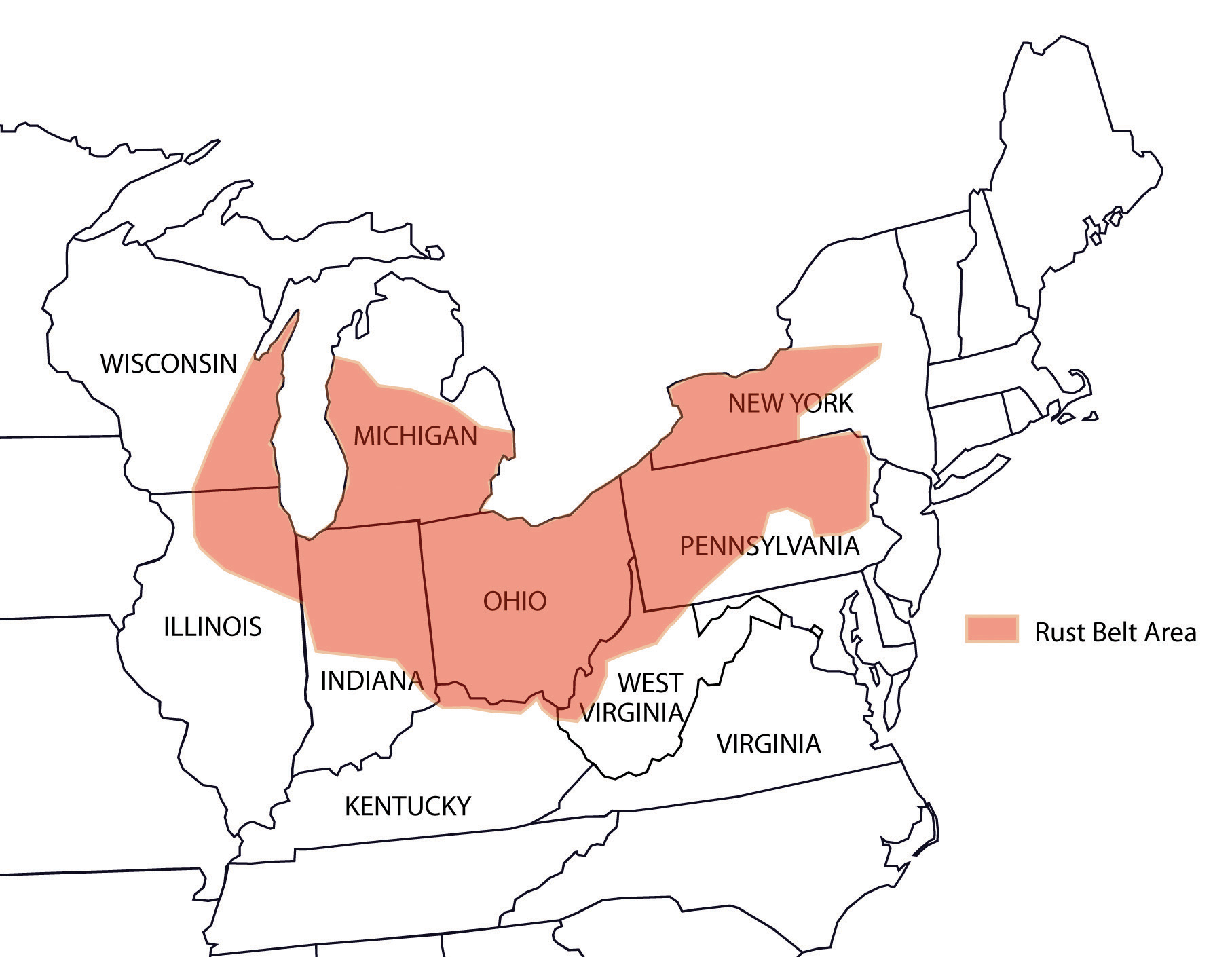

Figure 12.11

As more and more American factories closed in the 1970s and 1980s, commentators described the emergence of a Rust Belt that featured a net loss of jobs in many of the leading cities of the East and Midwest.

Portions of the Northeast and the Midwest soon became known as the “Rust BeltThe formerly dominant industrial region encompassing the northeastern United States. The term is a reference to the rust that accumulates on the factories after they were abandoned and the wide belt of industrial cities from St. Louis to Chicago and across Ohio to Pittsburgh.,” a name reflecting the thousands of factories that closed from St. Louis to Milwaukee and across the Great Lakes from Detroit back down to Pittsburgh and the Ohio River valley. The deindustrialization that caused the Rust Belt stretched beyond these borders and affected East Coast cities such as Baltimore and Philadelphia as well as other industrial communities throughout the nation. The demise of these Rust Belt factories that had once employed millions of blue-collar workers was complex. In many cases, employers found it was cheaper to start new factories in areas such as the South where labor unions were weak. Many other companies decided to open factories in other countries where wages were lower and safety and environmental laws did not apply.

With the loss of factory jobs came the decline of union membership and the rise of part-time and contract laborers who were not eligible for benefits and could be fired at any time. Unemployment increased to around 9 percent by 1975, while union membership dropped below 25 percent of nonfarm labor. An unprecedented number of married women entered the workforce in hopes of bolstering family income, mostly accepting low-paying service sector jobs. Cities likewise struggled with the simultaneous loss of middle-class workers and factories.

Downtowns areas responded by launching “urban renewalCivic efforts aimed at revitalizing and redeveloping urban areas with various construction projects. Urban renewal plans were often controversial because they involved a municipality claiming privately owned land through eminent domain. Eminent domain required compensation for owners of the land but often made no provision for families that rented homes in the areas that were to be redeveloped.” projects that sought to remove the blight of empty factories and build public works projects. In other cases, urban renewal was simply a euphemism for slum clearance. Minority neighborhoods were demolished to make room for interstate overpasses and other projects designed to connect the suburbs with downtown office buildings. Most urban renewal projects were conducted with little regard for the dispossessed. Although political support for public housing remained low in the 1970s, urban renewal soon required that a growing number of housing projects be built. Seeking to create low-cost units, most cities erected high-rise apartments on cheap land as far away from the middle class as possible. Those who supported the creation of housing projects, simply known as “projects” by many Americans, envisioned these low-cost units as a path toward upward mobility, a sort of halfway house for the working poor. However, these projects concentrated poverty in ways that quickly turned working-class neighborhoods into ghettos that were walled in by interstates and isolated from jobs and public services.

In the 1970s, a new phenomenon related to urban renewal called gentrificationA process that occurs when middle and upper-class residents move into formerly working-class neighborhoods. The process of gentrification often forces neighboring working-class families from their homes as rents and property values rise beyond their ability to pay. occurred in many American cities. Property values in older neighborhoods near urban centers had declined; an opportunity for investors who purchased entire city blocks evicted the remaining tenants, bulldozed or renovated older homes, and converted commercial buildings into loft-style condos. Developers also contracted with upscale retailers and bistros that appealed to young urban professionals, known collectively as “yuppies.” Racial and ethnic majorities were either evicted or simply priced out of their former neighborhoods, many facing few other housing options beyond the newly constructed projects. Black and ethnic businesses in these neighborhoods were likewise evicted or otherwise forced out, with few options to reestablish their businesses in an urban landscape that had become divided into gentrified downtowns, lily-white suburbs, and ghettoized housing projects.

As developers sought to modify the urban landscape of the 1970s, a different set of Americans became concerned with other aspects of the urban environment. Young adults in the 1960s became increasingly concerned about a variety of social issues such as environmental protection. The environmental movement saw its first major victory when Congress passed the Clean Air Act of 1963, a law that regulated auto and factory emissions. In response to a series of environmental disasters and the increasing political awareness of his constituents, Wisconsin senator Gaylord Nelson suggested that colleges and universities set aside April 22, 1970, as a day of learning and discussion of environmental issues. Utilizing the teach-in strategy of the antiwar movement, students and faculty at the University of Wisconsin and around the nation organized grassroots programs to raise awareness about pollution, toxic waste, and the preservation of natural resources. Earth DayA global holiday instituted by American college students and activists to promote environmental awareness every year on April 22 since 1970. has continued to be observed every year on April 22 since its inception in 1970 and is presently celebrated by more than 300 million people around the world.

Figure 12.12

College students and other young people led the way in promoting Earth Day, which was first celebrated in 1970. Participants conducted service projects, such as these students who are removing trash from the Potomac River.

The colossal success of the first Earth Day in 1970 demonstrated to US politicians that environmental protection had become a leading priority of their constituents. Dozens of environmental protection laws that had been rejected by Congress in previous decades were soon passed by large majorities. President Nixon soon responded by promoting the creation of a federal agency dedicated to environmental issues. Few historians consider Nixon as an environmentalist. As a result, the conservative president’s backing of environmental preservation demonstrates the success of grassroots organizers in forcing a pragmatic politician to support their agenda.

During his 1970 State of the Union address, Nixon called on Americans to “make our peace with nature” even as he was secretly working to prolong war in Vietnam. Later that year, Nixon consolidated and expanded existing federal antipollution programs into the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)A federal agency created in 1970 that conducts research and promotes education regarding the environment and is responsible for enforcing federal standards regarding environmental protection.. The new federal agency was granted authority to create and enforce standards regarding pollution with the guidance of Congress. For example, the EPA pressed Congress to outlaw the pesticide DDT in 1972 because of its toxicity to birds and fish, a danger that had been recognized since the 1950s and popularized by the best-selling novel Silent Spring. However, it was only after a lengthy study by the EPA in conjunction with Congress that the chemical was actually banned in the United States.

President Nixon also signed a more stringent Clean Air Act in 1970 that set a five-year deadline for the nation’s industries to meet new pollution standards. The law also required automakers to reduce vehicle emissions by 90 percent. Automakers complied with the law by including catalytic converters on every new car, a device that uses catalysts to alter the chemical properties of exhaust. These innovations slightly raised the cost of new automobiles and required consumers to switch to lead-free gasoline. The changes angered muscle-car enthusiasts but also led to a dramatic reduction in the smog that had plagued America’s cities since the 1950s.

Congress passed other laws in the early 1970s that limited the use of pesticides, protected endangered species, and required mine operators to limit the pollution that entered neighboring streams and ground water. Although millions of Americans participated in Earth Day celebrations and supported the idea of restricting pollution, many Americans were also concerned that the EPA’s new restrictions would raise costs for US businesses in ways that might accelerate the loss of domestic manufacturing jobs. As the economy continued to stagnate in the early and mid-1970s, corporate claims that new regulations were forcing plant closures became more concerning and led to some backlash against the EPA.

One of the biggest domestic controversies of the 1970s pitted corporate interests and the need for low-cost energy against concerns about environmental protection. Alaska was the last great frontier, but in 1968, massive oil reserves were discovered that many believed could reduce the nation’s dependence on foreign oil. Environmentalists opposed construction of the eight-hundred-mile Alaska Pipeline that would be necessary to transport oil from the isolated reserves in the Alaskan frontier to the nearest ice-free port in the Northern Pacific. As a compromise, the pipeline was built with a number of features to protect the environment. For example, the pipeline was elevated to allow for the migration of caribou, and hundreds of safety valves allowed engineers to immediately stop the flow of oil in case a leak developed anywhere along the line.

Leaks were an even greater concern when it came to nuclear power plants. Nuclear energy had been greeted by many as a panacea that would solve America’s energy crisis by reducing costs and pollution. Dozens of nuclear plants were operated safely until an accident occurred at Pennsylvania’s Three Mile IslandA nuclear plant near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania that overheated in 1979 and nearly led to a complete nuclear meltdown. The accident led to tougher industry regulations to prevent similar accidents in the future and also discouraged the construction of new nuclear plants. in March 1979. The accident itself was caused by human error, leading to the failure of the reactor’s cooling system. As a result, the reactor overheated creating the potential for a meltdown of the containment system that kept radioactive materials from being released into the environment. The actual radiation that had escaped was minimal, but the public was understandably concerned that tens of thousands of people might have died. The accident had cost hundreds of millions of dollars in cleanup operations and curtailed the construction of nuclear reactors in the next few decades. As a result, debates regarding the financial and environmental costs of coal-fired plants remained a leading issue in debates about the environment.

Economy and Government

As had been the case with the automobile and other new technologies of the past, the full impact of new technology that aided environmental protections, along with other major innovations of the 1970s such as microcomputers, would not be realized for nearly a decade. These new technologies created jobs in numerous fields throughout the 1970s. However, new technology also allowed companies to do more with fewer employees. For example, new technologies in communications created jobs but also allowed US companies to operate overseas more efficiently. By 1970, hundreds of US firms had become multinational corporations with operations around the globe. Not only did this globalizationThe development of a more integrated global economy with fewer trade restrictions that would permit corporations to compete equally around the globe. Many Americans oppose globalization for fear that permitting foreign firms to operate on the same terms as domestic companies could result the reductions of worker pay, environmental protection standards, or the loss of jobs overseas. of industry allow manufacturing operations to occur closer to the source of raw materials, but globalization also permitted US-based businesses to hire foreign employees for lower wages and avoid abiding by US labor standards and tax regulations.

Defenders of multinational corporations pointed out that these businesses improved international relations. At the very least, nations that traded with one another seldom went to war. They also claimed that America profited from overseas operations through declining prices for consumer goods and rising corporate dividends for US investors. While offshore operations might have been exempt from US taxation, globalization advocates pointed out that the federal government still received some revenue because the profits of individual stockholders were taxable. Critics countered that these companies were shipping jobs overseas and avoiding their fair share of taxation.

More distressing to many US workers than the details of corporate taxation, it appeared that globalization was an attack on the domestic job market. The United States had produced 40 percent of goods and services worldwide in 1950, but this percentage had declined to 25 percent by the 1970s. Others worried about the military implications of a US economy that lost its manufacturing base. After all, these individuals explained, US victory in World War II was based on the rapid conversion of existing factories to wartime production. By the late 1970s, the United States imported more goods than it exported. Each of these statistics warned of a possible return to America’s subordinate role in the global economy. Even more alarming to some, the nations that were making the largest gains in the production of automobiles and aircraft were Japan and Germany. While some Americans resented the fact that the rapid turnaround of these war-torn nations was partially due to US aid, others believed that German and Japanese economic recovery was inevitable. From this perspective, US aid had converted former rivals into two of America’s strongest allies in the global war against Communism. Japan and Germany’s economic recovery certainly benefited the US and global economy. However, the simultaneous decline of US industry was a bitter pill for World War II veterans, many of whom faced layoffs that may have been the result of international competition.

The late 1970s saw a resumption of economic growth and personal income, although these increases were modest in comparison with the rapid gains of developing economies. All of this added to the perception that the United States was on the decline. Inflation doubled between 1967 and 1973, while unemployment remained high at 8 percent. In the past, unemployment and inflation had usually moved in opposite directions. Prices increased when the economy was doing well but fell during periods of recession. This double whammy of rising inflation and unemployment led economists to create a new label to describe it: stagflationAn economic condition pairing high inflation with economic stagnation..