This is “The Benefits of Deficits”, section 29.3 from the book Theory and Applications of Economics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

29.3 The Benefits of Deficits

Learning Objectives

After you have read this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- When do countries run government budget deficits?

- Why might a country incur a government budget deficit?

To evaluate the merits of a balanced-budget amendment, we need to know why governments run deficits in the first place. After all, governments may have good reasons for these policies. We have seen one explanation for deficits: governments run deficits because of economic downturns. Reductions in gross domestic product (GDP), other things being equal, lead to increases in the budget deficit. We are more concerned with why governments choose to run persistent structural deficits, though. We first look to history for clues.

Government Debt: A Historical Perspective

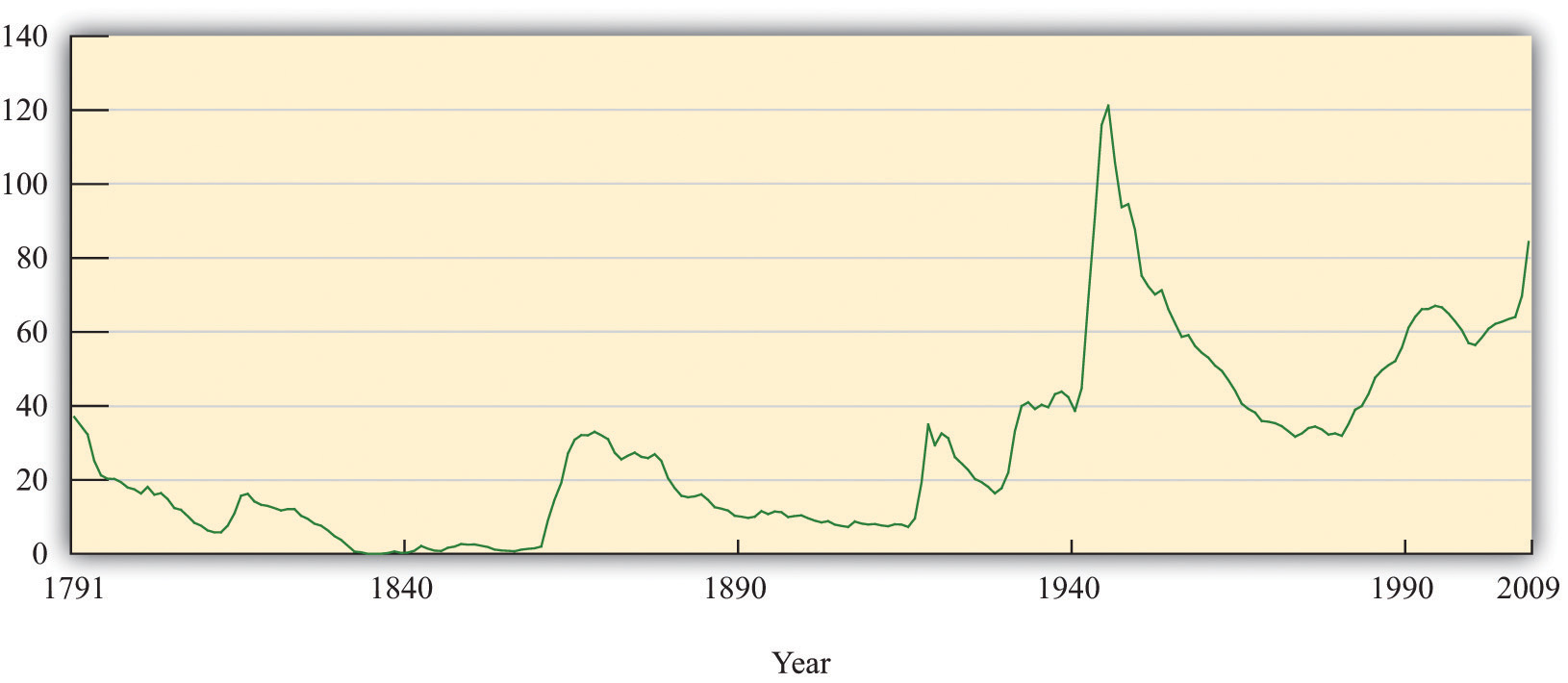

Figure 29.14 Ratio of US Debt to GDP, 1791–2009

Source: Debt data from http://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/histdebt/histdebt.htm; GDP data from https://eh.net/.

Figure 29.14 "Ratio of US Debt to GDP, 1791–2009" shows the ratio of US federal government debt to GDP from 1791 to 2009. The US Civil War in the 1860s, World War I in 1917, and World War II in the early 1940s all jump out from this figure. These are periods in which the stock of US federal debt soared. During the Civil War, the stock of debt was $64,842,287 in 1860 and peaked at $2,773,236,174 in 1866. The debt level was more than 40 times higher in 1866 than in 1860.

In 1915 (after World War I had started but before the United States had entered the war), the stock of debt was $3,058,136,873.16, not much more than the level in 1866. By 1919, the level of the debt was $27,390,970,113.12, an increase of almost 800 percent. During World War II, there was again a significant buildup of the debt. In 1940, the level of debt outstanding was $42,967,531,037.68, or about 42 percent of GDP. By 1946, this had increased by about 527 percent to $269,422,099,173.26. In 1946, the outstanding debt was 121 percent of GDP.

There are two other periods that show a significant buildup of the debt relative to GDP. The first is the Great Depression. This buildup was not due to a big increase in borrowing by the government. Rather, it was largely driven by the decline in the level of GDP (the denominator in the ratio). The second is the period from the 1980s to the present. The buildup of the debt in the 1980s was unprecedented in peacetime history.

Figure 29.14 "Ratio of US Debt to GDP, 1791–2009" also shows a dramatic asymmetry in the behavior of the debt-to-GDP ratio. Although the increases in this ratio are typically rather sudden, the decreases are much more gradual. Look again at the rapid increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio around the Civil War. After the Civil War ended, the debt-to-GDP ratio decreased but only slowly. As seen in the figure, the debt-to-GDP ratio decreased for about 45 years, from 1870 to 1916. Part of this decrease was due to the growth in GDP over the 45 years, and part was due to a decrease in nominal debt outstanding until around 1900.

Why Do Governments Run Deficits?

It is evident that during periods of war the debt is higher. What underlies this relationship between wars and deficits? War is certainly expensive. Take, for example, the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Congress has already appropriated about $1 trillion for these wars, and a Congressional Budget Office study projected the conflicts would eventually cost the United States about $2.4 trillion. When government purchases increase due to a war, a government can either increase taxes to pay for the war or issue government debt. Remember that when the government runs a deficit to pay for a war, it is borrowing from the general public. The government’s intertemporal budget constraint reminds us that—since government debt is ultimately paid for by taxes in the future—the choice is really between taxing households now or taxing them later. History tells us that deficits have been the method of choice: governments have chosen to tax future generations to pay for wars.

There are two arguments in favor of this policy:

- Fairness. Any gains from winning a war will be shared by future generations. Hence the costs should be shared as well: the government should finance the war with debt so that future generations will repay some of the obligations. To take an extreme case, suppose a country is fighting for its right to exist. If it wins the war, future generations will also benefit.

- Tax smoothing. A good fiscal policy is one where tax rates are relatively constant. In the face of a rapid increase in spending, such as a war, the best policy is one that pays for the spending increase over many periods of time, not in one year.

Taxation is expensive to the economy because it distorts economic decisions, such as saving and labor supply. The amount people want to work depends on their real wage, after taxes. So if tax rates are increased to finance government spending, this reduces the benefit from working. Put differently, increased income taxes increase the price of consumption relative to leisure. The fact that people work less when taxes increase is a distortionary effect of taxation. Instead of bunching all this distortionary taxation into a short amount of time, such as a year, it is more efficient for the government to spread the taxation over many years. This is called tax smoothingTo reduce the distortionary effects of taxes, a government will finance some current spending by issuing debt to spread the tax burden over time.. So by running a budget deficit, the government imposes relatively small distortions over many years rather than imposing large distortions within a single year.

Toolkit: Section 31.3 "The Labor Market"

For more analysis of the choice underlying labor supply, you can review the labor market in the toolkit.

Similar arguments apply to other cases in which governments engage in substantial spending. Imagine that the government is considering putting a large amount of resources into cancer research. The discovery of a successful cancer treatment would, of course, benefit many generations of citizens. Because households would share the gains in the future, the costs should be shared as well. By running a budget deficit, the government is able to distribute the costs across generations of citizens in parallel with the benefits. From the perspective of both fairness and efficiency, there are some gains to deficit spending.

More generally, we might want to make a distinction among different types of government purchases, just as we do among private purchases. We know that the national accounts distinguish consumption purchases (broadly speaking, things from which we get short-run benefit, such as food and movies) from investment purchases (things that bring long-term benefit, such as factories and machinery). Likewise, we might want to distinguish between government consumption, such as wages of employees at the Department of Motor Vehicles, from government investment, such as spending on cancer research. We could then argue that it makes more sense to borrow to finance government investment rather than government consumption.

Although a very nice idea in principle, this approach to the government accounts often founders on the practicalities and the politics of implementation. First, it is not at all clear how to classify many government expenditures. Was a launch of the space shuttle consumption or investment? What about the wages of teachers in the public schools? What about the money spent on national parks? Second, politicians would have a strong incentive to classify expenditures as investment rather than consumption, to justify deferring payment.

Another benefit of deficits is that they can play a role in economic stabilization.Chapter 22 "The Great Depression" spelled out in detail the role for fiscal policy in stabilizing output. In the short run, the level of economic activity can deviate from potential GDP. As a consequence, aggregate expenditures play a role in determining the level of output. Fiscal policy influences the level of aggregate expenditures. Changes in government purchases directly affect aggregate expenditures because they are a component of spending, and changes in taxes indirectly affect aggregate demand through their effect on consumption. Hence deficit spending can help to stabilize the economy.

In summary, there are several arguments for allowing governments to run deficits. We would forswear these benefits if we were to adopt a balanced-budget amendment.One of the arguments for deficits—funding wars—is an explicit exception (and the only such exception) written into the bill from that we quoted earlier. But we conclude by noting that there is a further, much less benign, reason for government deficits: they may benefit politicians even if they do not benefit the country as a whole. Deficits allow politicians to provide benefits to constituents today and leave the bill to future generations. If politicians and voters care more about current benefits than future costs, then they have a strong incentive to incur large deficits and let future generations worry about the consequences.

Deficits around the World

Do other countries also run deficits in the way that the United States does? Table 29.9 "Budget Deficits around the World, 2005*" summarizes the recent budgetary situation for several countries around the world. With the exception of Argentina, all the countries were running deficits in 2005.The table deliberately does not express the deficits relative to any measure of economic activity in the country. Thus it is hard to say whether these deficits are large or small. An Economics Detective exercise at the end of the chapter encourages you to look at this question.

Table 29.9 Budget Deficits around the World, 2005*

| Country | Revenues | Expenditures | Deficit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 42.6 | 39.98 | −2.62 |

| China | 392.1 | 424.3 | 32.2 |

| France | 1,006 | 1,114 | 108 |

| Germany | 1,249 | 1,362 | 113 |

| Italy | 785.7 | 861.5 | 75.8 |

| * Data are in millions of US dollars. | |||

Source: CIA Fact Book, http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/fields/2056.html.

France, Germany, and Italy are of particular interest. These three countries are part of the European Union (EU). In January 1999, when the Economic and Monetary Union was formed, a restriction on the budget deficits of EU countries went into effect. This measure was contained in legislation called the Stability and Growth Pact.This pact is discussed in detail in “Stability and Growth Pact,” European Commission Economic and Financial Affairs, accessed September 20, 2011, http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/sgp/index_en.htm. Its main component is a requirement that member countries keep deficits below a threshold of 3 percent of GDP. This threshold is not set to zero to allow countries the ability to deal with fluctuations in real GDP. In other words, although the EU does not impose a strict balanced-budget requirement, it does impose limits on member countries. In recent years, however, these limits have been exceeded. For example, in 2005, Germany’s deficit was more than 4.5 percent of its GDP. During the past few years, Germany has been in a recession and, as highlighted by Figure 29.7 "Deficit/Surplus and GDP", its deficit grew considerably. Instead of imposing contractionary fiscal policies to reduce its deficit, Germany allowed its deficit to grow outside the bounds set by the Stability and Growth Pact. The economic crisis of 2008 and subsequent recession that impacted many of the world economies had a further effect on the budget deficits of countries in Europe, contributing to severe debt crises and bailouts in Greece, Ireland, and Portugal.We examine what happened in these countries in Chapter 30 "The Global Financial Crisis".

Key Takeaways

- Countries run government budget deficits when faced with large expenditures, such as a war.

- By running a deficit, a government is able to spread distortionary taxes over time. Also, a deficit allows a government to allocate tax obligations across generations of citizens who all benefit from some form of government spending. Finally, stabilization policy often requires the government to run a deficit.

Checking Your Understanding

- What does it mean to say that a tax is “distortionary”?

- What is the political benefit to deficit spending?

- When does “fairness” provide a basis for running a deficit?