This is “Politics and Government”, section 10.1 from the book Sociology: Brief Edition (v. 1.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

10.1 Politics and Government

Learning Objectives

- Define power and the three types of authority.

- Distinguish the types of political systems.

- Discuss and assess pluralist and elite theories.

PoliticsThe distribution and exercise of power within a society. refers to the distribution and exercise of power within a society, and polityThe political institution through which power is distributed and exercised. refers to the political institution through which power is distributed and exercised. In any society decisions must be made regarding the allocation of resources and other matters. Except perhaps in the simplest societies, specific people and often specific organizations make these decisions. Depending on the society, they sometimes make these decisions solely to benefit themselves and other times make these decisions to benefit the society as a whole. Regardless of who benefits, a central point is this: some individuals and groups have more power than others. Because power is so essential to an understanding of politics, we begin our discussion of politics with a discussion of power.

Power and Authority

PowerThe ability to have one’s will carried out despite the resistance of others. refers to the ability to have one’s will carried out despite the resistance of others. Most of us have seen a striking example of raw power when we are driving a car and see a police car in our rearview mirror. At that particular moment, the driver of that car has enormous power over us. We make sure we strictly obey the speed limit and all other driving rules. If, alas, the police car’s lights are flashing, we stop the car, as otherwise we may be in for even bigger trouble. When the officer approaches our car, we ordinarily try to be as polite as possible and pray we do not get a ticket. When you were 16 and your parents told you to be home by midnight or else, your arrival home by this curfew again illustrated the use of power, in this case parental power. If a child in middle school gives her lunch to a bully who threatens her, that again is an example of the use of power, or, in this case, the misuse of power.

Figure 10.1

Power is the ability to exert one’s will over others. Police obviously have much power to exert their will over drivers suspected of traffic violations and over any individual suspected of a more serious crime.

© Thinkstock

These are all vivid examples of power, but the power that social scientists study is both grander and, often, more invisible (Wrong, 1996).Wrong, D. H. (1996). Power: Its forms, bases, and uses. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. Much of it occurs behind the scenes, and scholars continue to debate who is wielding it and for whose benefit they wield it. Many years ago Max Weber (1921/1978),Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology (G. Roth and C. Wittich, Eds.). Berkeley: University of California Press. (Original work published 1921) one of the founders of sociology discussed in earlier chapters, distinguished legitimate authority as a special type of power. Legitimate authorityPower whose use is considered just and appropriate by those over whom the power is exercised. (sometimes just called authority), Weber said, is power whose use is considered just and appropriate by those over whom the power is exercised. In short, if a society approves of the exercise of power in a particular way, then that power is also legitimate authority. The example of the police car in our rearview mirrors is an example of legitimate authority.

Weber’s keen insight lay in distinguishing different types of legitimate authority that characterize different types of societies, especially as they evolve from simple to more complex societies. He called these three types traditional authority, rational-legal authority, and charismatic authority. We turn to these now.

Traditional Authority

As the name implies, traditional authorityPower that is rooted in traditional, or long-standing, beliefs and practices of a society. is power that is rooted in traditional, or long-standing, beliefs and practices of a society. It exists and is assigned to particular individuals because of that society’s customs and traditions. Individuals enjoy traditional authority for at least one of two reasons. The first is inheritance, as certain individuals are granted traditional authority because they are the children or other relatives of people who already exercise traditional authority. The second reason individuals enjoy traditional authority is more religious: their societies believe they are anointed by God or the gods, depending on the society’s religious beliefs, to lead their society. Traditional authority is common in many preindustrial societies, where tradition and custom are so important, but also in more modern monarchies (discussed shortly), where a king, queen, or prince enjoys power because she or he comes from a royal family.

Traditional authority is granted to individuals regardless of their qualifications. They do not have to possess any special skills to receive and wield their authority, as their claim to it is based solely on their bloodline or supposed divine designation. An individual granted traditional authority can be intelligent or stupid, fair or arbitrary, and exciting or boring but receives the authority just the same because of custom and tradition. As not all individuals granted traditional authority are particularly well qualified to use it, societies governed by traditional authority sometimes find that individuals bestowed it are not always up to the job.

Rational-Legal Authority

If traditional authority derives from custom and tradition, rational-legal authorityAuthority that derives from law and is based on a belief in the legitimacy of a society’s laws and rules and in the right of leaders acting under these rules to make decisions and set policy. derives from law and is based on a belief in the legitimacy of a society’s laws and rules and in the right of leaders to act under these rules to make decisions and set policy. This form of authority is a hallmark of modern democracies, where power is given to people elected by voters, and the rules for wielding that power are usually set forth in a constitution, a charter, or another written document. Whereas traditional authority resides in an individual because of inheritance or divine designation, rational-legal authority resides in the office that an individual fills, not in the individual per se. The authority of the president of the United States thus resides in the office of the presidency, not in the individual who happens to be president. When that individual leaves office, authority transfers to the next president. This transfer is usually smooth and stable, and one of the marvels of democracy is that officeholders are replaced in elections without revolutions having to be necessary. We might not have voted for the person who wins the presidency, but we accept that person’s authority as our president when he (so far it has always been a “he”) assumes office.

Rational-legal authority helps ensure an orderly transfer of power in a time of crisis. When John F. Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, Vice President Lyndon Johnson was immediately sworn in as the next president. When Richard Nixon resigned his office in disgrace in 1974 because of his involvement in the Watergate scandal, Vice President Gerald Ford (who himself had become vice president after Spiro Agnew resigned because of financial corruption) became president. Because the U.S. Constitution provided for the transfer of power when the presidency was vacant, and because U.S. leaders and members of the public accept the authority of the Constitution on these and so many other matters, the transfer of power in 1963 and 1974 was smooth and orderly.

Charismatic Authority

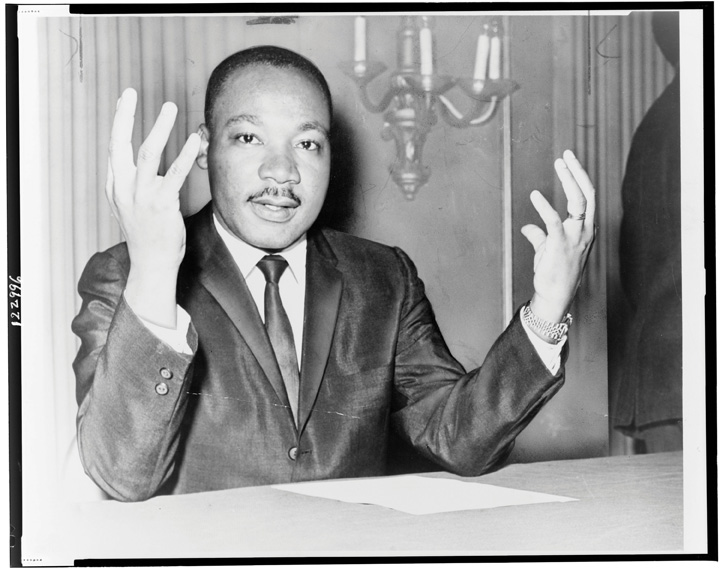

Charismatic authorityAuthority that stems from an individual’s extraordinary personal qualities and from that individual’s hold over followers because of these qualities. stems from an individual’s extraordinary personal qualities and from that individual’s hold over followers because of these qualities. Such charismatic individuals may exercise authority over a whole society or only a specific group within a larger society. They can exercise authority for good and for bad, as this brief list of charismatic leaders indicates: Joan of Arc, Adolf Hitler, Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Jesus Christ, Muhammad, and Buddha. Each of these individuals had extraordinary personal qualities that led their followers to admire them and to follow their orders or requests for action.

Figure 10.2

Much of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s appeal as a civil rights leader stemmed from his extraordinary speaking skills and other personal qualities that accounted for his charismatic authority.

Source: Photo courtesy of U.S. Library of Congress, http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3c22996.

Weber emphasized that charismatic authority is less stable than traditional authority or rational-legal authority. The reason for this is simple: once charismatic leaders die, their authority dies as well. Although a charismatic leader’s example may continue to inspire people long after the leader dies, it is difficult for another leader to come along and command people’s devotion as intensely. After the deaths of all the charismatic leaders named in the preceding paragraph, no one came close to replacing them in the hearts and minds of their followers.

Charismatic authority can reside in a person who came to a position of leadership because of traditional or rational-legal authority. Over the centuries, several kings and queens of England and other European nations were charismatic individuals as well (while some were far from charismatic). A few U.S. presidents—Washington, Lincoln, both Roosevelts, Kennedy, Reagan, and, for all his faults, even Clinton—also were charismatic, and much of their popularity stemmed from various personal qualities that attracted the public and sometimes even the press. Ronald Reagan, for example, was often called the Teflon president, because he was so loved by much of the public that accusations of ineptitude or malfeasance did not stick to him (Lanoue, 1988).Lanoue, D. J. (1988). From Camelot to the Teflon president: Economics and presidential popularity since 1960. New York, NY: Greenwood Press.

Types of Political Systems

Various states and governments obviously exist around the world. In this context, state means the political unit within which power and authority reside. This unit can be a whole nation or a subdivision within a nation. Thus the nations of the world are sometimes referred to as states (or nation-states), as are subdivisions within a nation, such as, in the United States, California, New York, and Texas. Government means the group of persons who direct the political affairs of a state, but it can also mean the type of rule by which a state is run. Another term for this second meaning of government is political system, which we will use here along with government. The type of government under which people live has fundamental implications for their freedom, their welfare, and even their lives. Accordingly we briefly review the major political systems in the world today.

Democracy

The type of government with which we are most familiar is democracy, or a political system in which citizens govern themselves either directly or indirectly. The term democracy comes from Greek and means “rule of the people.” In Lincoln’s stirring words from the Gettysburg Address, democracy is “government of the people, by the people, for the people.” In direct (or pure) democracies, people make their own decisions about the policies and distribution of resources that affect them directly. An example of such a democracy in action is the New England town meeting, where the residents of a town meet once a year and vote on budgetary and other matters. However, such direct democracies are impractical when the number of people gets beyond a few hundred. Representative democracies are thus much more common. In these types of democracies, people elect officials to represent them in legislative votes on matters affecting the population.

As this definition implies, perhaps the most important feature of representative democracies is voting in elections. When the United States was established more than 230 years ago, most of the world’s governments were monarchies or other authoritarian regimes (discussed shortly). Like the colonists, people in these nations chafed under arbitrary power. The example of the American Revolution and the stirring words of its Declaration of Independence helped inspire the French Revolution of 1789 and other revolutions since, as people around the world have died in order to win the right to vote and to have political freedom.

Of course, democracies are not perfect. Their decision-making process can be quite slow and inefficient; decisions may be made for special interests and not “for the people”; and, as we have seen in earlier chapters, pervasive inequalities of social class, race and ethnicity, gender, and age can exist. Moreover, in not all democracies have all people enjoyed the right to vote. In the United States, for example, African Americans could not vote until after the Civil War, with the passage of the 15th Amendment in 1870, and women did not win the right to vote until 1920, with the passage of the 19th Amendment.

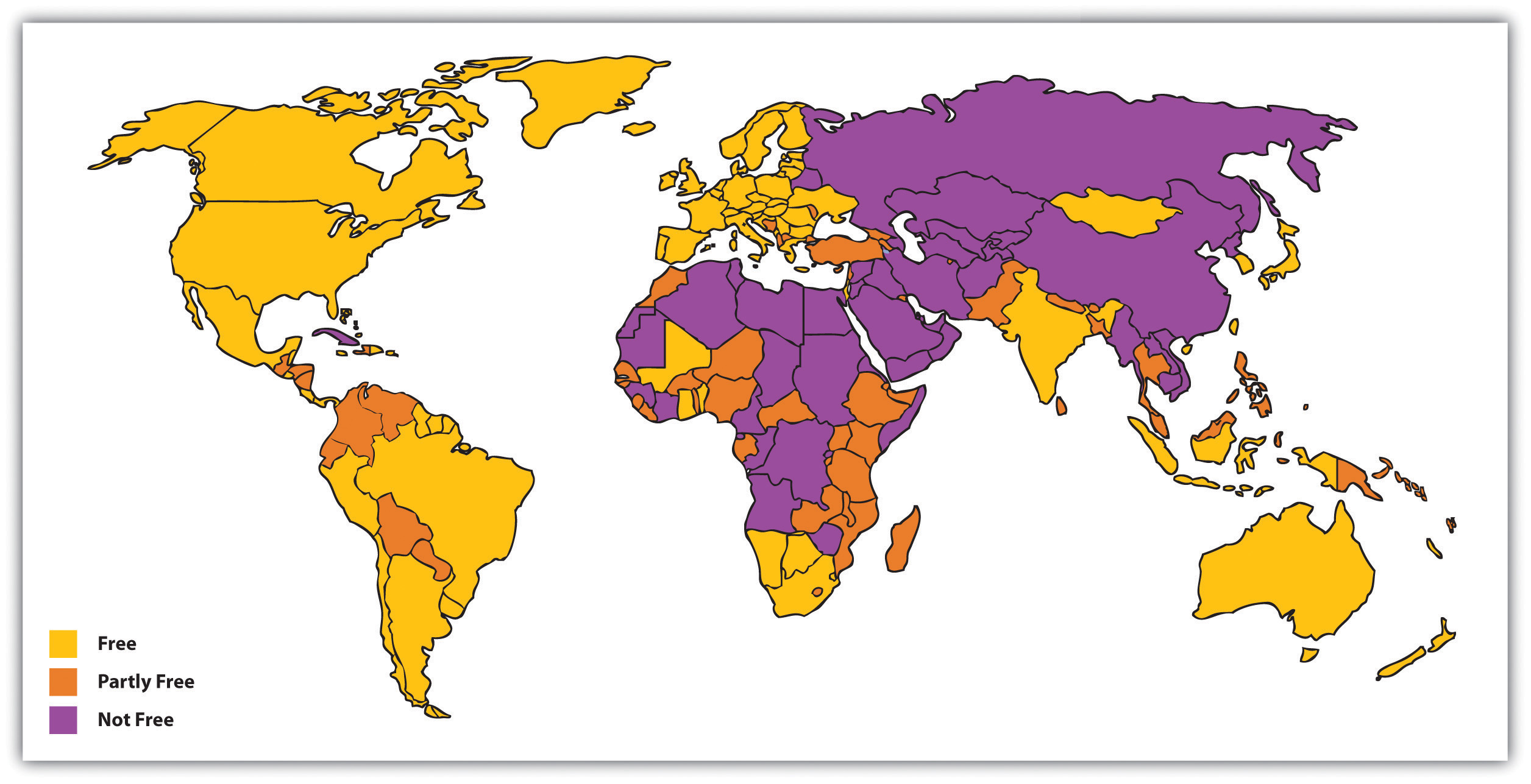

In addition to generally enjoying the right to vote, people in democracies also have more freedom than those in other types of governments. Figure 10.3 "Freedom Around the World (Based on Extent of Political Rights and Civil Liberties)" depicts the nations of the world according to the extent of their political rights and civil liberties.

Figure 10.3 Freedom Around the World (Based on Extent of Political Rights and Civil Liberties)

Source: Adapted from Freedom House. (2010). Map of freedom in the world, 2010. Retrieved from http://www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=363&year=2010.

The freest nations are found in North America, Western Europe, and certain other parts of the world, while the least free lie in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

Monarchy

Figure 10.4

Queen Elizabeth II of England holds a largely ceremonial position, but earlier English monarchs held much more power.

Monarchy is a political system in which power resides in a single family that rules from one generation to the next generation. The power the family enjoys is traditional authority, and many monarchs command respect because their subjects bestow this type of authority upon them. Other monarchs, however, have ensured respect through arbitrary power and even terror. Royal families still rule today, but their power has declined from centuries ago. Today the Queen of England holds a largely ceremonial position, but her predecessors on the throne wielded much more power.

This example reflects a historical change in types of monarchies (Finer, 1997)Finer, S. E. (1997). The history of government from the earliest times. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. from absolute monarchies to constitutional monarchies. In absolute monarchies, the royal family claims a divine right to rule and exercises considerable power over their kingdom. Absolute monarchies were common in both ancient (e.g., Egypt) and medieval (e.g., England and China) times but slowly gave way to constitutional monarchies. In these monarchies, the royal family serves a symbolic and ceremonial role and enjoys little, if any, real power. Instead the executive and legislative branches of government—the prime minister and parliament in several nations—run the government, even if the royal family continues to command admiration and respect. Constitutional monarchies exist today in several nations, including Denmark, Great Britain, Norway, Spain, and Sweden.

Authoritarianism and Totalitarianism

Authoritarianism and totalitarianism are general terms for nondemocratic political systems ruled by an individual or a group of individuals who are not freely elected by their populations and who often exercise arbitrary power. To be more specific, authoritarianism refers to political systems in which an individual or a group of individuals holds power, restricts or prohibits popular participation in governance, and represses dissent. Totalitarianism refers to political systems that include all the features of authoritarianism but are even more repressive as they try to regulate and control all aspects of citizens’ lives and fortunes. People can be imprisoned for deviating from acceptable practices or may even be killed if they dissent in the mildest of ways. The purple nations in Figure 10.3 "Freedom Around the World (Based on Extent of Political Rights and Civil Liberties)" are mostly totalitarian regimes, and the orange ones are authoritarian regimes.

Compared to democracies and monarchies, authoritarian and totalitarian governments are more unstable politically. The major reason for this is that these governments enjoy no legitimate authority. Instead their power rests on fear and repression. Because their populations do not willingly lend their obedience to their political systems, and because their political systems treat them so poorly, they are more likely than populations in democratic states to want to rebel. Sometimes they do rebel, and if the rebellion becomes sufficiently massive and widespread, a revolution occurs. In contrast, populations in democratic states usually perceive that they are treated more or less fairly and, further, that they can change things they do not like through the electoral process. Seeing no need for revolution, they do not revolt.

Since World War II, which helped make the United States an international power, the United States has opposed some authoritarian and totalitarian regimes while supporting others. The Cold War pitted the United States and its allies against Communist nations, primarily the Soviet Union, China, Cuba, and North Korea. But at the same time the United States opposed these authoritarian governments, it supported many others, including those in Chile, Guatemala, and South Vietnam, that repressed and even murdered their own citizens who dared to engage in the kind of dissent constitutionally protected in the United States (Sullivan, 2008).Sullivan, M. (2008). American adventurism abroad: Invasions, interventions, and regime changes since World War II (Rev. and expanded ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell. Earlier in U.S. history, the federal and state governments repressed dissent by passing legislation that prohibited criticism of World War I and then by imprisoning citizens who criticized that war (Goldstein, 2001).Goldstein, R. J. (2001). Political repression in modern America from 1870 to 1976 (Rev. ed.). Urbana: University of Illinois Press. During the 1960s and 1970s, the FBI, the CIA, and other federal agencies spied on tens of thousands of citizens who engaged in dissent protected by the First Amendment (Cunningham, 2004).Cunningham, D. (2004). There’s something happening here: The New Left, the Klan, and FBI counterintelligence. Berkeley: University of California Press. While the United States remains a beacon of freedom and hope to much of the world’s peoples, its own support for repression in the recent and more distant past suggests that eternal vigilance is needed to ensure that “liberty and justice for all” is not just an empty slogan.

Theories of Power and Society

These remarks raise some important questions: Just how democratic is the United States? Whose interests do our elected representatives serve? Is political power concentrated in the hands of a few or widely dispersed among all segments of the population? These and other related questions lie at the heart of theories of power and society. Let’s take a brief look at some of these theories.

Pluralist Theory: A Functionalist Perspective

Recall (from Chapter 1 "Sociology and the Sociological Perspective") that the smooth running of society is a central concern of functionalist theory. When applied to the issue of political power, functionalist theory takes the form of pluralist theoryThe view that political power in the United States and other democracies is dispersed among several veto groups that compete in the political process for resources and influence., which says that political power in the United States and other democracies is dispersed among several “veto groups” that compete in the political process for resources and influence. Sometimes one particular veto group may win and other times another group may win, but in the long run they win and lose equally and no one group has any more influence than another (Dahl, 1956).Dahl, R. A. (1956). A preface to democratic theory. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

As this process unfolds, says pluralist theory, the government might be an active participant, but it is an impartial participant. Just as parents act as impartial arbiters when their children argue with each other, so does the government act as a neutral referee to ensure that the competition among veto groups is done fairly, that no group acquires undue influence, and that the needs and interests of the citizenry are kept in mind.

The process of veto-group competition and its supervision by the government is functional for society, according to pluralist theory, for three reasons. First, it ensures that conflict among the groups is channeled within the political process instead of turning into outright hostility. Second, the competition among the veto groups means that all of these groups achieve their goals to at least some degree. Third, the government’s supervision helps ensure that the outcome of the group competition benefits society as a whole.

Elite Theories: Conflict Perspectives

Several elite theoriesTheories that say that power in a democracy is concentrated in the hands of a relatively few individuals, families, and/or organizations. dispute the pluralist model. According to these theories, power in democratic societies is concentrated in the hands of a few wealthy individuals and organizations—or economic elites—that exert inordinate influence on the government and can shape its decisions to benefit their own interests. Far from being a neutral referee over competition among veto groups, the government is said to be controlled by economic elites or at least to cater to their needs and interests. As should be clear, elite theories fall squarely within the conflict perspective as outlined in Chapter 1 "Sociology and the Sociological Perspective".

Perhaps the most famous elite theory is the power-elite theory of C. Wright Mills (1956).Mills, C. W. (1956). The power elite. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. According to Mills, the power eliteC. Wright Mills’s term for the leaders from government, big business, and the military who he thought constitute a ruling class that controls society and works for its own interests, not for the interests of the citizenry. is composed of government, big business, and the military, which together constitute a ruling class that controls society and works for its own interests, not for the interests of the citizenry. Members of the power elite, Mills said, see each other socially and serve together on the boards of directors of corporations, charitable organizations, and other bodies. When Cabinet members, senators, and top generals and other military officials retire, they often become corporate executives. Conversely, corporate executives often become Cabinet members and other key political appointees. This circulating of the elites helps ensure their dominance over American life.

Mills’s power-elite model remains popular, but other elite theories exist. They differ from Mills’s model in several ways, including their view of the composition of the ruling class. Several theories see the ruling class as composed mostly of the large corporations and wealthiest individuals and see government and the military serving the needs of the ruling class rather than being part of it, as Mills implied. G. William Domhoff (2010)Domhoff, G. W. (2010). Who rules America: Challenges to corporate and class dominance (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill. says that the ruling class is composed of the richest one-half to one percent of the population that controls more than half the nation’s wealth, sits on the boards of directors just mentioned, and are members of the same social clubs and other voluntary organizations. Their control of corporations and other economic and political bodies helps to maintain their inordinate influence over American life and politics.

Other elite theories say the government is more autonomous—not as controlled by the ruling class—than Mills thought. Sometimes the government takes the side of the ruling class and corporate interests, but sometimes it opposes them. Such relative autonomy, these theories say, helps ensure the legitimacy of the state, because if it always took the side of the rich it would look too biased and lose the support of the populace. In the long run, then, the relative autonomy of the state helps maintain ruling class control by making the masses feel the state is impartial when in fact it is not (Thompson, 1975).Thompson, E. P. (1975). Whigs and hunters: The origin of the Black Act. London, England: Allen Lane.

Assessing Pluralist and Elite Theories

As a way of understanding power in the United States and other democracies, pluralist and elite theories have much to offer, but neither type of theory presents a complete picture. Pluralist theory errs in seeing all special-interest groups as equally powerful and influential. Certainly the success of lobbying groups such as the National Rifle Association and the American Medical Association in the political and economic systems is testimony to the fact that not all special-interest groups are created equal. Pluralist theory also errs in seeing the government as a neutral referee. Sometimes the government does take sides on behalf of corporations by acting, or failing to act, in a certain way.

For example, U.S. antipollution laws and regulations are notoriously weak because of the influence of major corporations on the political process. Through their campaign contributions, lobbying, and other types of influence, corporations help ensure that pollution controls are kept as weak as possible (Simon, 2008).Simon, D. R. (2008). Elite deviance (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. This problem received worldwide attention in the spring of 2010 after the explosion of an oil rig owned by BP, a major oil and energy company, spilled tens of thousands of barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico in the biggest environmental disaster in U.S. history. As the oil was leaking, news reports emphasized that individuals or political action committees (PACs) associated with BP had contributed $500,000 to U.S. candidates in the 2008 elections, that BP had spent $16 million on lobbying in 2009, and that the oil and gas industry had spent tens of millions of dollars on lobbying that year (Montopoli, 2010).Montopoli, B. (2010, May 5). BP spent millions on lobbying, campaign donations. CBS News. Retrieved from http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-503544_162-20004240 -503544.html

Although these examples support the views of elite theories, the theories also paint too simple a picture. They err in implying that the ruling class acts as a unified force in protecting its interests. Corporations sometimes do oppose each other for profits and sometimes even steal secrets from each other, and governments do not always support the ruling class. For example, the U.S. government has tried to reduce tobacco smoking despite the wealth and influence of tobacco companies. While the United States, then, does not entirely fit the pluralist vision of power and society, neither does it entirely fit the elite vision. Yet the evidence that does exist of elite influence on the American political and economic systems reminds us that government is not always “of the people, by the people, for the people,” however much we may wish it otherwise.

Key Takeaways

- According to Max Weber, the three types of legitimate authority are traditional, rational-legal, and charismatic.

- The major types of political systems include democracy, monarchy, and authoritarianism and totalitarianism.

- Pluralist theory assumes that political power in democracies is dispersed among several veto groups that compete equally for resources and influence, while elite theories assume that power is instead concentrated in the hands of a few wealthy individuals and organizations who exert inordinate influence on the government and can shape its decisions to benefit their own interests.

For Your Review

- Think of someone, either a person you have known or a national or historic figure, whom you regard as a charismatic leader. What is it about this person that makes her or him charismatic?

- Do pluralist or elite theories better explain the exercise of power in the United States? Explain your answer.