This is “International Finance”, section 15.2 from the book Macroeconomics Principles (v. 1.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

15.2 International Finance

Learning Objectives

- Define a country’s balance of payments, and explain what is included on the current and capital accounts.

- Assuming that the market for a country’s currency is in equilibrium, explain why the current account balance will always be the negative of the capital account balance.

- Summarize the economic arguments per se against public opposition to a current account deficit and a capital account surplus.

There is an important difference between trade that flows, say, from one city to another and trade that flows from one nation to another. Unless they share a common currency, as some of the nations of the European Union do, trade among nations requires that currencies be exchanged as well as goods and services. Suppose, for example, that buyers in Mexico purchase silk produced in China. The Mexican buyers will pay in Mexico’s currency, the peso; the manufacturers of the silk must be paid in China’s currency, the yuan. The flow of trade between Mexico and China thus requires an exchange of pesos for yuan.

This section examines the relationship between spending that flows into a country and spending that flows out of it. These spending flows include not only spending for a nation’s exports and imports, but payments to owners of assets in other countries, international transfer payments, and purchases of foreign assets. The balance between spending flowing into a country and spending flowing out of it is called its balance of paymentsThe balance between spending flowing into a country and spending flowing out..

We will simplify our analysis by ignoring international transfer payments, which occur when an individual, firm, or government makes a gift to an individual, firm, or government in another country. Foreign aid is an example of an international transfer payment. International transfer payments play a relatively minor role in the international financial transactions of most countries; ignoring them will not change our basic conclusions.

A second simplification will be to treat payments to foreign owners of factors of production used in a country as imports and payments received by owners of factors of production used in other countries as exports. This is the approach when we use GNP rather than GDP as the measure of a country’s output.

These two simplifications leave two reasons for demanding a country’s currency: for foreigners to purchase a country’s goods and services (that is, its exports) and to purchase assets in the country. A country’s currency is supplied in order to purchase foreign currencies. A country’s currency is thus supplied for two reasons: to purchase goods and services from other countries (that is, its imports) and to purchase assets in other countries.

We studied the determination of exchange rates in the chapter on how financial markets work. We saw that, in general, exchange rates are determined by demand and supply and that the markets for the currencies of most nations can be regarded as being in equilibrium. Exchange rates adjust quickly, so that the quantity of a currency demanded equals the quantity of the currency supplied.

Our analysis will deal with flows of spending between the domestic economy and the rest of the world. Suppose, for example, that we are analyzing Japan’s economy and its transactions with the rest of the world. The purchase by a buyer in, say, Germany of bonds issued by a Japanese corporation would be part of the rest-of-world demand for yen to buy Japanese assets. Adding export demand to asset demand by people, firms, and governments outside a country, we get the total demand for a country’s currency.

A domestic economy’s currency is supplied to purchase currencies in the rest of the world. In an analysis of the market for Japanese yen, for example, yen are supplied when people, firms, and government agencies in Japan purchase goods and services from the rest of the world. This part of the supply of yen equals Japanese imports. Yen are also supplied so that holders of yen can acquire assets from other countries.

Equilibrium in the market for a country’s currency implies that the quantity of a particular country’s currency demanded equals the quantity supplied. Equilibrium thus implies that

Equation 15.1

In turn, the quantity of a currency demanded is from two sources:

- Exports

- Rest-of-world purchases of domestic assets

The quantity supplied of a currency is from two sources:

- Imports

- Domestic purchases of rest-of-world assets

Therefore, we can rewrite Equation 15.1 as

Equation 15.2

Accounting for International Payments

In this section, we will build a set of accounts to track international payments. To do this, we will use the equilibrium condition for foreign exchange markets given in Equation 15.2. We will see that the balance between a country’s purchases of foreign assets and foreign purchases of the country’s assets will have important effects on net exports, and thus on aggregate demand.

We can rearrange the terms in Equation 15.2 to write the following:

Equation 15.3

Equation 15.3 represents an extremely important relationship. Let us examine it carefully.

The left side of the equation is net exports. It is the balance between spending flowing from foreign countries into a particular country for the purchase of its goods and services and spending flowing out of the country for the purchase of goods and services produced in other countries. The current accountAn accounting statement that includes all spending flows across a nation’s border except those that represent purchases of assets. is an accounting statement that includes all spending flows across a nation’s border except those that represent purchases of assets. The balance on current accountSpending flowing into an economy from the rest of the world on current account less spending flowing from the nation to the rest of the world on current account. equals spending flowing into an economy from the rest of the world on current account less spending flowing from the nation to the rest of the world on current account. Given our two simplifying assumptions—that there are no international transfer payments and that we can treat rest-of-world purchases of domestic factor services as exports and domestic purchases of rest-of-world factor services as imports—the balance on current account equals net exports. When the balance on current account is positive, spending flowing in for the purchase of goods and services exceeds spending that flows out, and the economy has a current account surplusSituation that occurs when spending flowing in for the purchase of goods and services exceeds spending that flows out. (i.e., net exports are positive in our simplified analysis). When the balance on current account is negative, spending for goods and services that flows out of the country exceeds spending that flows in, and the economy has a current account deficitSituation that occurs when spending for goods and services that flows out of the country exceeds spending that flows in. (i.e., net exports are negative in our simplified analysis).

A country’s capital accountAn accounting statement of spending flows into and out of the country during a particular period for purchases of assets. is an accounting statement of spending flows into and out of the country during a particular period for purchases of assets. The term within the parentheses on the right side of the equation gives the balance between rest-of-world purchases of domestic assets and domestic purchases of rest-of-world assets; this balance is a country’s balance on capital accountThe balance between rest-of-world purchases of domestic assets and domestic purchases of rest-of-world assets.. A positive balance on capital account is a capital account surplusA positive balance on capital account.. A capital account surplus means that buyers in the rest of the world are purchasing more of a country’s assets than buyers in the domestic economy are spending on rest-of-world assets. A negative balance on capital account is a capital account deficitA negative balance on capital account.. It implies that buyers in the domestic economy are purchasing a greater volume of assets in other countries than buyers in other countries are spending on the domestic economy’s assets. Remember that the balance on capital account is the term inside the parentheses on the right-hand side of Equation 15.3 and that there is a minus sign outside the parentheses.

Equation 15.3 tells us that a country’s balance on current account equals the negative of its balance on capital account. Suppose, for example, that buyers in the rest of the world are spending $100 billion per year acquiring assets in a country, while that country’s buyers are spending $70 billion per year to acquire assets in the rest of the world. The country thus has a capital account surplus of $30 billion per year. Equation 15.3 tells us the country must have a current account deficit of $30 billion per year.

Alternatively, suppose buyers from the rest of the world acquire $25 billion of a country’s assets per year and that buyers in that country buy $40 billion per year in assets in other countries. The economy has a capital account deficit of $15 billion; its capital account balance equals −$15 billion. Equation 15.3 tells us it thus has a current account surplus of $15 billion. In general, we may write the following:

Equation 15.4

Assuming the market for a nation’s currency is in equilibrium, a capital account surplus necessarily means a current account deficit. A capital account deficit necessarily means a current account surplus. Similarly, a current account surplus implies a capital account deficit; a current account deficit implies a capital account surplus. Whenever the market for a country’s currency is in equilibrium, and it virtually always is in the absence of exchange rate controls, Equation 15.3 is an identity—it must be true. Thus, any surplus or deficit in the current account means the capital account has an offsetting deficit or surplus.

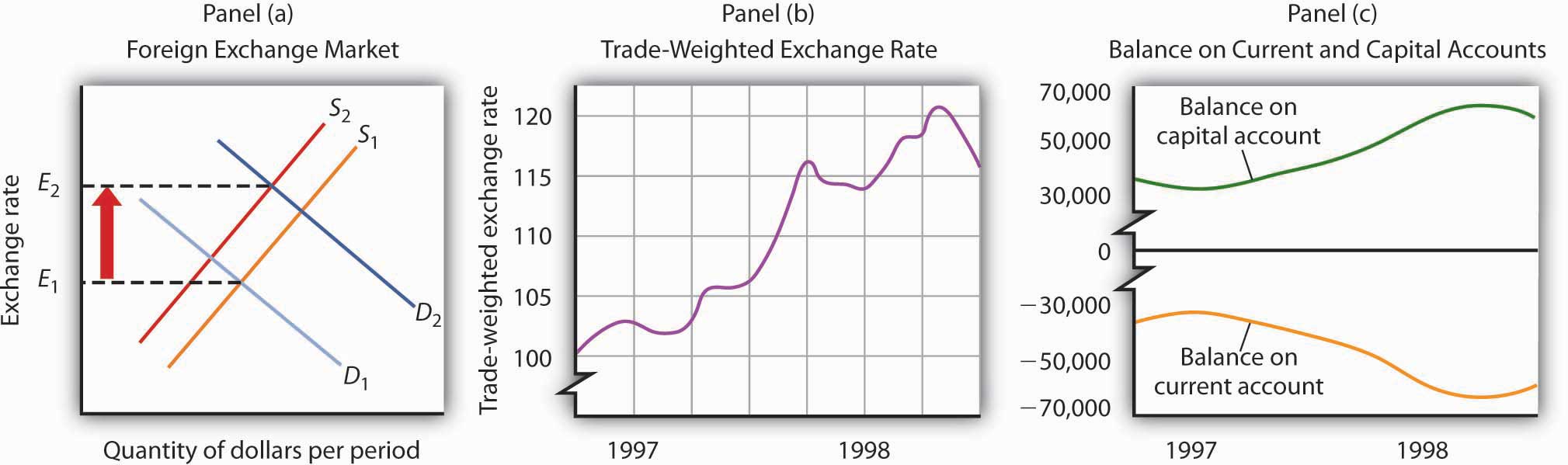

The accounting relationships underlying international finance hold as long as a country’s currency market is in equilibrium. But what are the economic forces at work that cause these equalities to hold? Consider how global turmoil in 1997 and 1998, discussed in the chapter opening, affected the United States. Holders of assets, including foreign currencies, in the rest of the world were understandably concerned that the values of those assets might fall. To avoid a plunge in the values of their own holdings, many of them purchased U.S. assets, including U.S. dollars. Those purchases of U.S. assets increased the U.S. surplus on capital account. To buy those assets, foreign purchasers had to purchase dollars. Also, U.S. citizens became less willing to hold foreign assets, and their preference for holding U.S. assets increased. United States citizens were thus less willing to supply dollars to the foreign exchange market. The increased demand for dollars and the decreased supply of dollars sent the U.S. exchange rate higher, as shown in Panel (a) of Figure 15.6 "A Change in the Exchange Rate Affected the U.S. Current and Capital Accounts in 1997 and 1998". Panel (b) shows the actual movement of the U.S. exchange rate in 1997 and 1998. Notice the sharp increases in the exchange rate throughout most of the period. A higher exchange rate in the United States reduces U.S. exports and increases U.S. imports, increasing the current account deficit. Panel (c) shows the movement of the current and capital accounts in the United States in 1997 and 1998. Notice that as the capital account surplus increased, the current account deficit rose. A reduction in the U.S. exchange rate at the end of 1998 coincided with a movement of these balances in the opposite direction.

Figure 15.6 A Change in the Exchange Rate Affected the U.S. Current and Capital Accounts in 1997 and 1998

Turmoil in currency markets all over the world in 1997 and 1998 increased the demand for dollars and decreased the supply of dollars in the foreign exchange market, which caused an increase in the U.S. exchange rate, as shown in Panel (a). Panel (b) shows actual values of the U.S. exchange rate during that period; Panel (c) shows U.S. balances on current and on capital accounts. Notice that the balance on capital account generally rose while the balance on current account generally fell.

Deficits and Surpluses: Good or Bad?

For the past quarter century, the United States has had a current account deficit and a capital account surplus. Is this good or bad?

Viewed from the perspective of consumers, neither phenomenon seems to pose a problem. A current account deficit is likely to imply a trade deficit. That means more goods and services are flowing into the country than are flowing out. A capital account surplus means more spending is flowing into the country for the purchase of assets than is flowing out. It is hard to see the harm in any of that.

Public opinion, however, appears to regard a current account deficit and capital account surplus as highly undesirable, perhaps because people associate a trade deficit with a loss of jobs. But that is erroneous; employment in the long run is determined by forces that have nothing to do with a trade deficit. An increase in the trade deficit (that is, a reduction in net exports) reduces aggregate demand in the short run, but net exports are only one component of aggregate demand. Other factors—consumption, investment, and government purchases—affect aggregate demand as well. There is no reason a trade deficit should imply a loss of jobs.

What about foreign purchases of U.S. assets? One objection to such purchases is that if foreigners own U.S. assets, they will receive the income from those assets—spending will flow out of the country. But it is hard to see the harm in paying income to financial investors. When someone buys a bond issued by Microsoft, interest payments will flow from Microsoft to the bond holder. Does Microsoft view the purchase of its bond as a bad thing? Of course not. Despite the fact that Microsoft’s payment of interest on the bond and the ultimate repayment of the face value of the bond will exceed what the company originally received from the bond purchaser, Microsoft is surely not unhappy with the arrangement. It expects to put that money to more productive use; that is the reason it issued the bond in the first place.

A second concern about foreign asset purchases is that the United States in some sense loses sovereignty when foreigners buy its assets. But why should this be a problem? Foreign-owned firms competing in U.S. markets are at the mercy of those markets, as are firms owned by U.S. nationals. Foreign owners of U.S. real estate have no special power. What about foreign buyers of bonds issued by the U.S. government? Foreigners owned about 28% of these bonds at the end of September 2008; they are thus the creditors for about 28% of the national debt. But this position hardly puts them in control of the government of the United States. They hold an obligation of the U.S. government to pay them a certain amount of U.S. dollars on a certain date, nothing more. A foreign owner could sell his or her bonds, but more than $100 billion worth of these bonds are sold every day. The resale of U.S. bonds by a foreign owner will not affect the U.S. government.

In short, there is no economic justification for concern about having a current account deficit and a capital account surplus—nor would there be an economic reason to be concerned about the opposite state of affairs. The important feature of international trade is its potential to improve living standards for people. It is not a game in which current account balances are the scorecard.

Key Takeaways

- The balance of payments shows spending flowing into and out of a country.

- The current account is an accounting statement that includes all spending flows across a nation’s border except those that represent purchases of assets. In our simplified analysis, the balance on current account equals net exports.

- A nation’s balance on capital account equals rest-of-world purchases of its assets during a period less its purchases of rest-of-world assets.

- Provided that the market for a nation’s currency is in equilibrium, the balance on current account equals the negative of the balance on capital account.

- There is no economic justification for viewing any particular current account balance as a good or bad thing.

Try It!

Use Equation 15.3 and Equation 15.4 to compute the variables given in each of the following. Assume that the market for a nation’s currency is in equilibrium and that the balance on current account equals net exports.

- Suppose U.S. exports equal $300 billion, imports equal $400 billion, and rest-of-world purchases of U.S. assets equal $150 billion. What is the U.S. balance on current account? The balance on capital account? What is the value of U.S. purchases of rest-of-world assets?

- Suppose Japanese exports equal ¥200 trillion (¥ is the symbol for the yen, Japan’s currency), imports equal ¥120 trillion, and Japan’s purchases of rest-of-world assets equal ¥90 trillion. What is the balance on Japan’s current account? The balance on Japan’s capital account? What is the value of rest-of-world purchases of Japan’s assets?

- Suppose Britain’s purchases of rest-of-world assets equal £70 billion (£ is the symbol for the pound, Britain’s currency), rest-of-world purchases of British assets equal £90 billion, and Britain’s exports equal £40 billion. What is Britain’s balance on capital account? Its balance on current account? Its total imports?

- Suppose Mexico’s purchases of rest-of-world assets equal $500 billion ($ is the symbol for the peso, Mexico’s currency), rest-of-world purchases of Mexico’s assets equal $700 billion, and Mexico’s imports equal $550 billion. What is Mexico’s balance on capital account? Its balance on current account? Its total exports?

Case in Point: Alan Greenspan on the U.S. Current Account Deficit

Figure 15.7

The growing U.S. current account deficit has generated considerable alarm. But, is there cause for alarm? In a speech in December 2005, former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan analyzed what he feels are the causes of the growing deficit and explains how the U.S. current account deficit may, under certain circumstances, decrease over time without a crisis.

“In November 2003, I noted that we saw little evidence of stress in funding the U.S. current account deficit even though the real exchange rate for the dollar, on net, had declined more than 10% since early 2002. … Two years later, little has changed except that our current account deficit has grown still larger. Most policy makers marvel at the seeming ease with which the United States continues to finance its current account deficit.

“Of course, deficits that cumulate to ever-increasing net external debt, with its attendant rise in servicing costs, cannot persist indefinitely. At some point, foreign investors will balk at a growing concentration of claims against U.S. residents … and will begin to alter their portfolios. … The rise of the U.S. current account deficit over the past decade appears to have coincided with a pronounced new phase of globalization that is characterized by a major acceleration in U.S. productivity growth and the decline in what economists call home bias. In brief, home bias is the parochial tendency of persons, though faced with comparable or superior foreign opportunities, to invest domestic savings in the home country. The decline in home bias is reflected in savers increasingly reaching across national borders to invest in foreign assets. The rise in U.S. productivity attracted much of those savings toward investments in the United States. …

“Accordingly, it is tempting to conclude that the U.S. current account deficit is essentially a byproduct of long-term secular forces, and thus is largely benign. After all, we do seem to have been able to finance our international current account deficit with relative ease in recent years.

“But does the apparent continued rise in the deficits of U.S. individual households and nonfinancial businesses themselves reflect growing economic strain? (We do not think so.) And does it matter how those deficits of individual economic entities are being financed? Specifically, does the recent growing proportion of these deficits being financed, net, by foreigners matter? …

“If the currently disturbing drift toward protectionism is contained and markets remain sufficiently flexible, changing terms of trade, interest rates, asset prices, and exchange rates will cause U.S. saving to rise, reducing the need for foreign finance, and reversing the trend of the past decade toward increasing reliance on it. If, however, the pernicious drift toward fiscal instability in the United States and elsewhere is not arrested and is compounded by a protectionist reversal of globalization, the adjustment process could be quite painful for the world economy.”

Source: Alan Greenspan, “International Imbalances” (speech, Advancing Enterprise Conference, London, England, December 2, 2005), available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2005/200512022/default.htm.

Answers to Try It! Problems

-

All figures are in billions of U.S. dollars per period. The left-hand side of Equation 15.3 is the current account balance

Exports − imports = $300 − $400 = −$100Using Equation 15.4, the balance on capital account is

−$100 = −(capital account balance)Solving this equation for the capital account balance, we find that it is $100. The term in parentheses on the right-hand side of Equation 15.3 is also the balance on capital account. We thus have

$100 = $150 − U.S. purchases of rest-of-world assetsSolving this for U.S. purchase of rest-of-world assets, we find they are $50.

-

All figures are in trillions of yen per period. The left-hand side of Equation 15.3 is the current account balance

Exports − imports = ¥200 − ¥120 = ¥80Using Equation 15.4, the balance on capital account is

¥80 = −(capital account balance)Solving this equation for the capital account balance, we find that it is −¥80. The term in parentheses on the right-hand side of Equation 15.3 is also the balance on capital account. We thus have

−¥80 = rest-of-world purchases of Japan’s assets − ¥90Solving this for the rest-of-world purchases of Japan’s assets, we find they are ¥10.

-

All figures are in billions of pounds per period. The term in parentheses on the right-hand side of Equation 15.3 is the balance on capital account. We thus have

£90 − £70 = £20Using Equation 15.4, the balance on current account is

Current account balance = −(£20)The left-hand side of Equation 15.3 is also the current account balance

£40 − imports = −£20Solving for imports, we find they are £60. Britain’s balance on current account is −£20 billion, its balance on capital account is £20 billion, and its total imports equal £60 billion per period.

-

All figures are in billions of pesos per period. The term in parentheses on the right-hand side of Equation 15.3 is the balance on capital account. We thus have

$700 − $500 = $200Using Equation 15.4, the balance on current account is

Current account balance = −($200)The left-hand side of Equation 15.3 is also the current account balance

Exports − $550 = −$200Solving for exports, we find they are $350.