This is “The International Sector: An Introduction”, section 15.1 from the book Macroeconomics Principles (v. 1.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

15.1 The International Sector: An Introduction

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the main arguments economists make in support of free trade.

- Explain the determinants of net exports and tell how each affects aggregate demand.

How important is international trade?

Take a look at the labels on some of your clothing. You are likely to find that the clothes in your closet came from all over the globe. Look around any parking lot. You may find cars from Japan, Korea, Sweden, Britain, Germany, France, and Italy—and even the United States! Do you use a computer? Even if it is an American computer, its components are likely to have been assembled in Indonesia or in some other country. Visit the grocery store. Much of the produce may come from Latin America and Asia.

The international market is important not just in terms of the goods and services it provides to a country, but as a market for that country’s goods and services. Because foreign demand for U.S. exports is almost as large as investment and government purchases as a component of aggregate demand, it can be very important in terms of growth. The increase in exports from 2000 to 2007, for example, accounted for almost 20% of the gain in U.S. real GDP during that period. For the period 2004 to 2007, the increase in exports accounted for about 30% of the gain.

The Case for Trade

International trade increases the quantity of goods and services available to the world’s consumers. By allocating resources according to the principle of comparative advantage, trade allows nations to consume combinations of goods and services they would be unable to produce on their own, combinations that lie outside each country’s production possibilities curve.

A country has a comparative advantage in the production of a good if it can produce that good at a lower opportunity cost than can other countries. If each country specializes in the production of goods in which it has a comparative advantage and trades those goods for things in which other countries have a comparative advantage, global production of all goods and services will be increased. The result can be higher levels of consumption for all.

If international trade allows expanded world production of goods and services, it follows that restrictions on trade will reduce world production. That, in a nutshell, is the economic case for free trade. It suggests that restrictions on trade, such as a tariffA tax imposed on imported goods and services., a tax imposed on imported goods and services, or a quotaA ceiling on the quantity of specific goods and services that can be imported, which reduces world living standards., a ceiling on the quantity of specific goods and services that can be imported, reduce world living standards.

The conceptual argument for free trade is a compelling one; virtually all economists support policies that reduce barriers to trade. Economists were among the most outspoken advocates for the 1993 ratification of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which virtually eliminated trade restrictions between Mexico, the United States, and Canada, and the 2004 Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), which did the same for trade between the United States, Central America, and the Dominican Republic. Most economists have also been strong supporters of worldwide reductions in trade barriers, including the 1994 ratification of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), a pact slashing tariffs and easing quotas among 117 nations, including the United States, and the Doha round of World Trade Organization negotiations, named after the site of the first meeting in Doha, Qatar, in 2001 and still continuing. In Europe, member nations of the European Union (EU) have virtually eliminated trade barriers among themselves, and 15 EU nations now have a common currency, the euro, and a single central bank, the European Central Bank, established in 1999. Trade barriers have also been slashed among the economies of Latin America and of Southeast Asia. A treaty has been signed that calls for elimination of trade barriers among the developed nations of the Pacific Rim (including the United States and Japan) by 2010 and among all Pacific rim nations by 2020.

The global embrace of the idea of free trade demonstrates the triumph of economic ideas over powerful forces that oppose free trade. One source of opposition to free trade comes from the owners of factors of production used in industries in which a nation lacks a comparative advantage.

A related argument against free trade is that it not only reduces employment in some sectors but also reduces employment in the economy as a whole. In the long run, this argument is clearly wrong. The economy’s natural level of employment is determined by forces unrelated to trade policy, and employment moves to its natural level in the long run.

Further, trade has no effect on real wage levels for the economy as a whole. The equilibrium real wage depends on the economy’s demand for and supply curve of labor. Trade affects neither.

In the short run, trade does affect aggregate demand. Net exports are one component of aggregate demand; a change in net exports shifts the aggregate demand curve and affects real GDP in the short run. All other things unchanged, a reduction in net exports reduces aggregate demand, and an increase in net exports increases it.

Protectionist sentiment always rises during recessions. The recession that began in the United States in 2007 is no exception. The stimulus bill contained a provision ordering U.S. government agencies and contractors to purchase goods and services produced in the United States in preference to goods and services from other countries. Our trading partners have already begun threatening a trade war as a result of this provision. The stimulus bill does say that the “buy America first” provision should be “consistent with international obligations.” As yet, it is not clear how significant this provision would become.

The Rising Importance of International Trade

International trade is important, and its importance is increasing. From 1965 to 2007, world output rose by about 300%. But the gains in total exports were even more spectacular; they soared by over 1,000%!

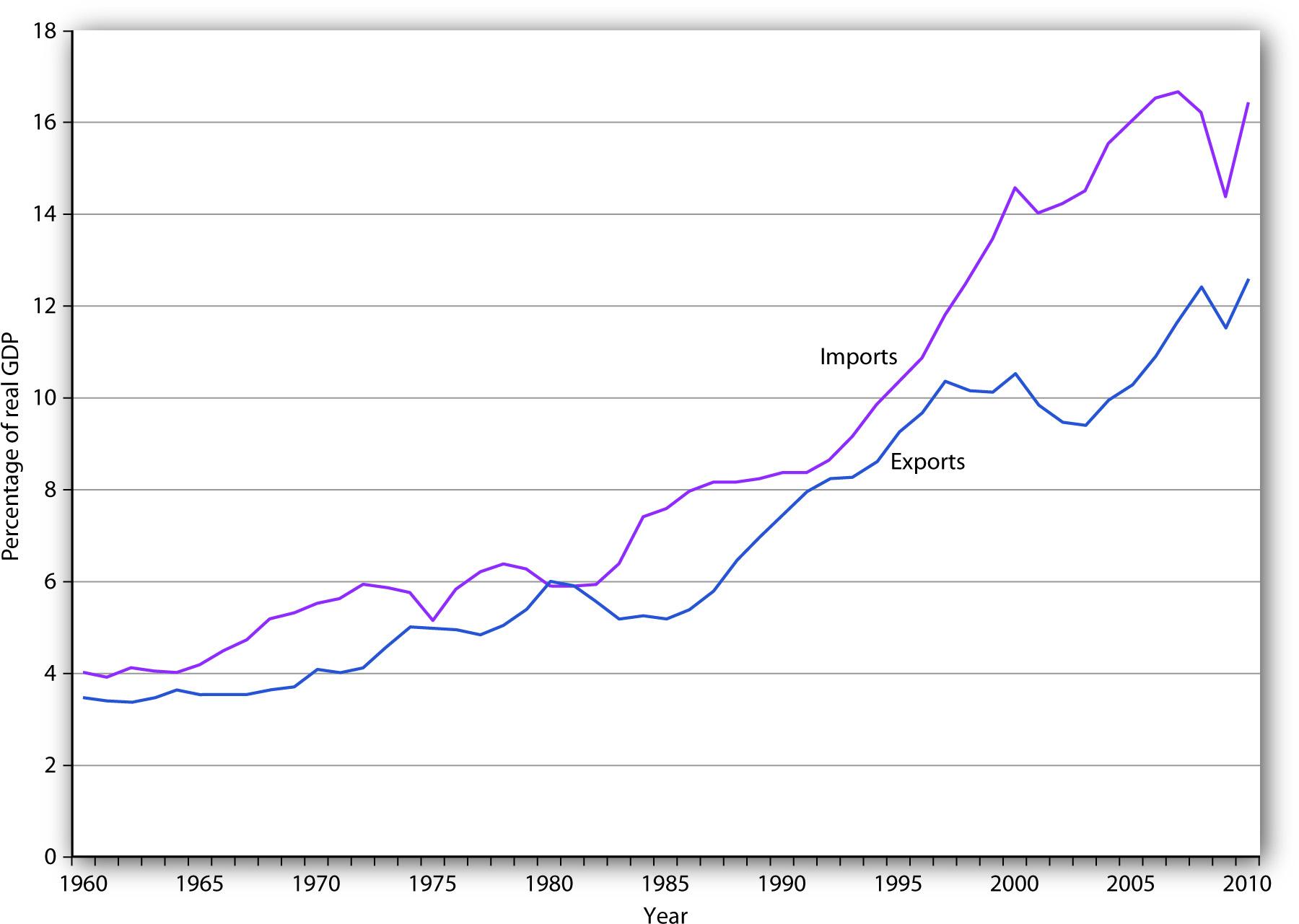

While international trade was rising around the world, it was playing a more significant role in the United States as well. In 1960, exports represented just 3.5% of real GDP; by 2010, exports accounted for 12.6% of real GDP. Figure 15.1 "U.S. Exports and Imports Relative to U.S. Real GDP, 1960–2010" shows the growth in exports and imports as a percentage of real GDP in the United States from 1960 to 2010.

Why has world trade risen so spectacularly? Two factors have been important. First, advances in transportation and communication have dramatically reduced the costs of moving goods around the globe. The development of shipping containerization that allows cargo to be moved seamlessly from trucks or trains to ships, which began in 1956, drastically reduced the cost of moving goods around the world, by as much as 90%. As a result, the numbers of container ships and their capacities have markedly increased.For an interesting history of this remarkable development, see Marc Levinson, The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006). Second, we have already seen that trade barriers between countries have fallen and are likely to continue to fall.

Figure 15.1 U.S. Exports and Imports Relative to U.S. Real GDP, 1960–2010

The chart shows exports and imports as a percentage of real GDP from 1960 through the third quarter of 2010.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, NIPA Table 1.1.6 (Revised November 23, 2010). Data are through the third quarter of 2010.

Net Exports and the Economy

As trade has become more important worldwide, exports and imports have assumed increased importance in nearly every country on the planet. We have already discussed the increased shares of U.S. real GDP represented by exports and by imports. We will find in this section that the economy both influences, and is influenced by, net exports. First, we will examine the determinants of net exports and then discuss the ways in which net exports affect aggregate demand.

Determinants of Net Exports

Net exports equal exports minus imports. Many of the same forces affect both exports and imports, albeit in different ways.

Income

As incomes in other nations rise, the people of those nations will be able to buy more goods and services—including foreign goods and services. Any one country’s exports thus will increase as incomes rise in other countries and will fall as incomes drop in other countries.

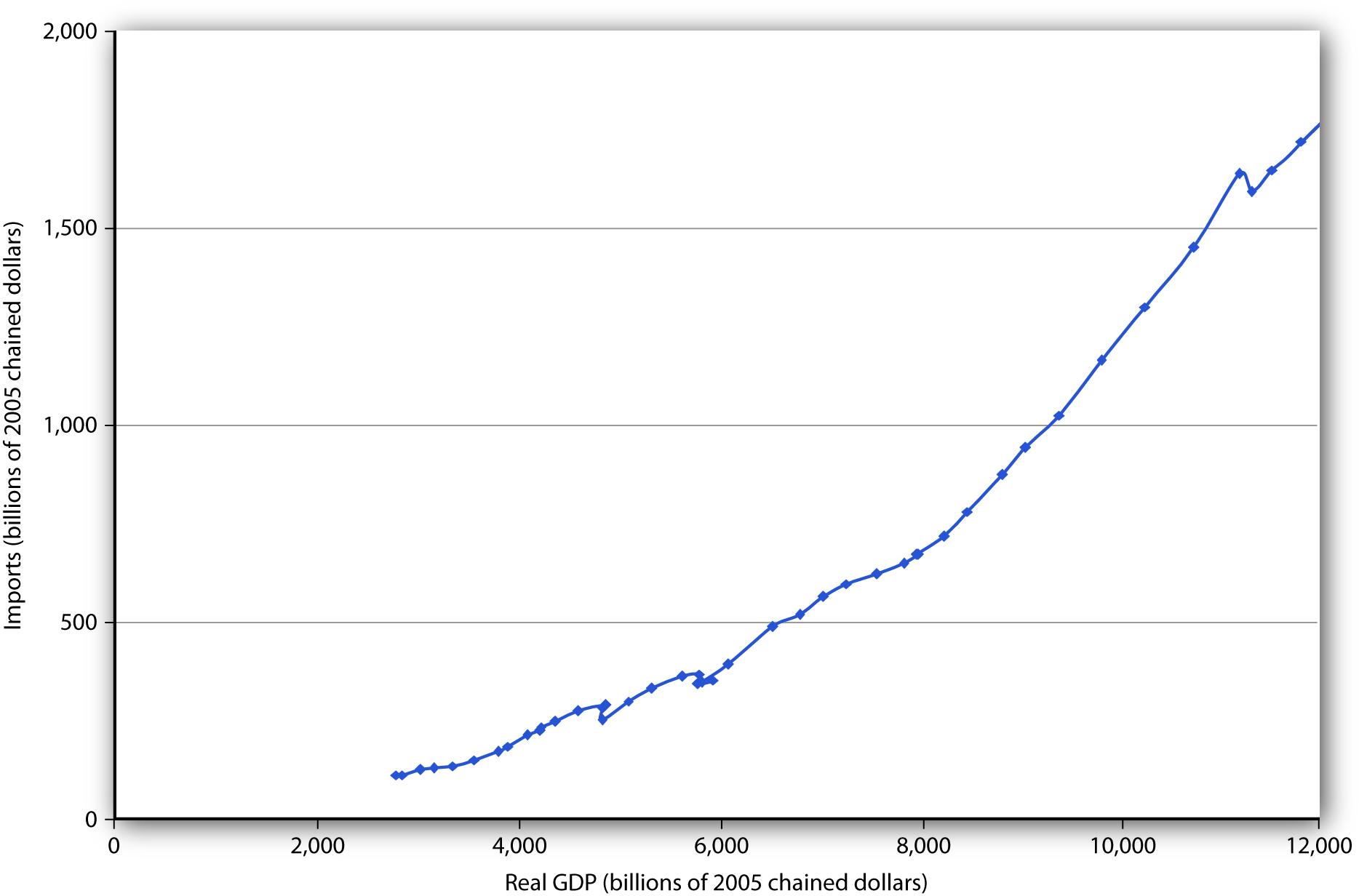

A nation’s own level of income affects its imports the same way it affects consumption. As consumers have more income, they will buy more goods and services. Because some of those goods and services are produced in other nations, imports will rise. An increase in real GDP thus boosts imports; a reduction in real GDP reduces imports. Figure 15.2 "U.S. Real GDP and Imports, 1960–2010" shows the relationship between real GDP and the real level of import spending in the United States from 1960 through 2010. Notice that the observations lie close to a straight line one could draw through them and resemble a consumption function.

Figure 15.2 U.S. Real GDP and Imports, 1960–2010

The chart shows annual values of U.S. real imports and real GDP from 1960 through 2010. The observations lie quite close to a straight line.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, NIPA Table 1.1.6 (Revised November 23, 2010). Data are through the third quarter of 2010.

Relative Prices

A change in the price level within a nation simultaneously affects exports and imports. A higher price level in the United States, for example, makes U.S. exports more expensive for foreigners and thus tends to reduce exports. At the same time, a higher price level in the United States makes foreign goods and services relatively more attractive to U.S. buyers and thus increases imports. A higher price level therefore reduces net exports. A lower price level encourages exports and reduces imports, increasing net exports. As we saw in the chapter that introduced the aggregate demand and supply model, the negative relationship between net exports and the price level is called the international trade effect and is one reason for the negative slope of the aggregate demand curve.

The Exchange Rate

The purchase of U.S. goods and services by foreign buyers generally requires the purchase of dollars, because U.S. suppliers want to be paid in their own currency. Similarly, purchases of foreign goods and services by U.S. buyers generally require the purchase of foreign currencies, because foreign suppliers want to be paid in their own currencies. An increase in the exchange rate means foreigners must pay more for dollars, and must thus pay more for U.S. goods and services. It therefore reduces U.S. exports. At the same time, a higher exchange rate means that a dollar buys more foreign currency. That makes foreign goods and services cheaper for U.S. buyers, so imports are likely to rise. An increase in the exchange rate should thus tend to reduce net exports. A reduction in the exchange rate should increase net exports.

Trade Policies

A country’s exports depend on its own trade policies as well as the trade policies of other countries. A country may be able to increase its exports by providing some form of government assistance (such as special tax considerations for companies that export goods and services, government promotional efforts, assistance with research, or subsidies). A country’s exports are also affected by the degree to which other countries restrict or encourage imports. The United States, for example, has sought changes in Japanese policies toward products such as U.S.-grown rice. Japan banned rice imports in the past, arguing it needed to protect its own producers. That has been a costly strategy; consumers in Japan typically pay as much as 10 times the price consumers in the United States pay for rice. Japan has given in to pressure from the United States and other nations to end its ban on foreign rice as part of the GATT accord. That will increase U.S. exports and lower rice prices in Japan.

Similarly, a country’s imports are affected by its trade policies and by the policies of its trading partners. A country can limit its imports of some goods and services by imposing tariffs or quotas on them—it may even ban the importation of some items. If foreign governments subsidize the manufacture of a particular good, then domestic imports of the good might increase. For example, if the governments of countries trading with the United States were to subsidize the production of steel, then U.S. companies would find it cheaper to purchase steel from abroad than at home, increasing U.S. imports of steel.

Preferences and Technology

Consumer preferences are one determinant of the consumption of any good or service; a shift in preferences for a foreign-produced good will affect the level of imports of that good. The preference among the French for movies and music produced in the United States has boosted French imports of these services. Indeed, the shift in French preferences has been so strong that the government of France, claiming a threat to its cultural heritage, has restricted the showing of films produced in the United States. French radio stations are fined if more than 40% of the music they play is from “foreign” (in most cases, U.S.) rock groups.

Changes in technology can affect the kinds of capital firms import. Technological changes have changed production worldwide toward the application of computers to manufacturing processes, for example. This has led to increased demand for high-tech capital equipment, a sector in which the United States has a comparative advantage and tends to dominate world production. This has boosted net exports in the United States.

Net Exports and Aggregate Demand

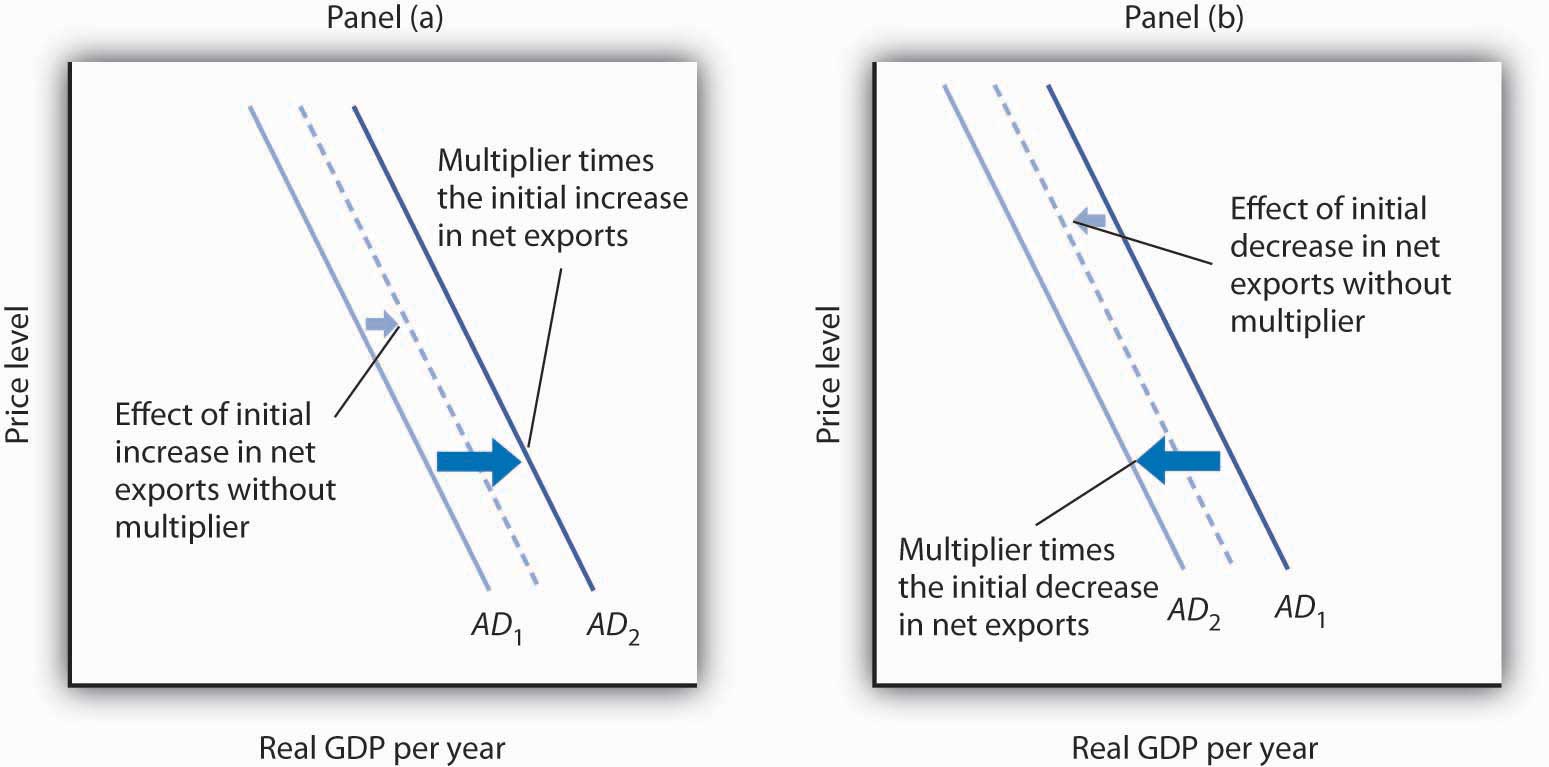

Net exports affect both the slope and the position of the aggregate demand curve. A change in the price level causes a change in net exports that moves the economy along its aggregate demand curve. This is the international trade effect. A change in net exports produced by one of the other determinants of net exports listed above (incomes and price levels in other nations, the exchange rate, trade policies, and preferences and technology) will shift the aggregate demand curve. The magnitude of this shift equals the change in net exports times the multiplier, as shown in Figure 15.3 "Changes in Net Exports and Aggregate Demand". Panel (a) shows an increase in net exports; Panel (b) shows a reduction. In both cases, the aggregate demand curve shifts by the multiplier times the initial change in net exports, provided there is no other change in the other components of aggregate demand.

Figure 15.3 Changes in Net Exports and Aggregate Demand

In Panel (a), an increase in net exports shifts the aggregate demand curve to the right by an amount equal to the multiplier times the initial change in net exports. In Panel (b), an equal reduction in net exports shifts the aggregate demand curve to the left by the same amount.

Changes in net exports that shift the aggregate demand curve can have a significant impact on the economy. The United States, for example, experienced a slowdown in the rate of increase in real GDP in the second and third quarters of 1998—virtually all of this slowing was the result of a reduction in net exports caused by recessions that staggered economies throughout Asia. The Asian slide reduced incomes there and thus reduced Asian demand for U.S. goods and services. We will see in the next section another mechanism through which difficulties in other nations can cause changes in a nation’s net exports and its level of real GDP in the short run.

Key Takeaways

- International trade allows the world’s resources to be allocated on the basis of comparative advantage and thus allows the production of a larger quantity of goods and services than would be available without trade.

- Trade affects neither the economy’s natural level of employment nor its real wage in the long run; those are determined by the demand for and the supply curve of labor.

- Growth in international trade has outpaced growth in world output over the past five decades.

- The chief determinants of net exports are domestic and foreign incomes, relative price levels, exchange rates, domestic and foreign trade policies, and preferences and technology.

- A change in the price level causes a change in net exports that moves the economy along its aggregate demand curve. This is the international trade effect. A change in net exports produced by one of the other determinants of net exports will shift the aggregate demand curve by an amount equal to the initial change in net exports times the multiplier.

Try It!

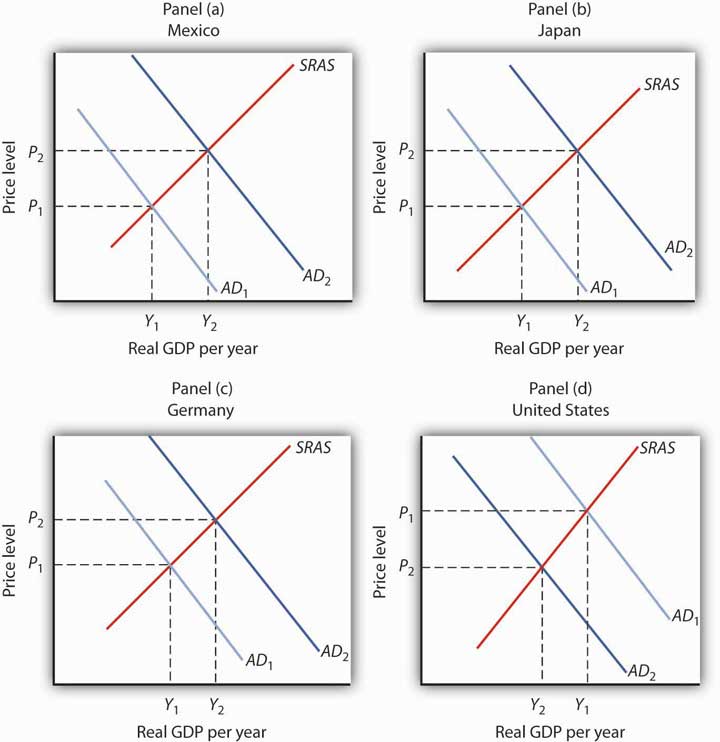

Draw graphs showing the aggregate demand and short-run aggregate supply curves in each of four countries: Mexico, Japan, Germany, and the United States. Assume that each country is initially in equilibrium with a real GDP of Y1 and a price level of P1. Now show how each of the following four events would affect aggregate demand, the price level, and real GDP in the country indicated.

- The United States is the largest foreign purchaser of goods and services from Mexico. How does an expansion in the United States affect real GDP and the price level in Mexico?

- Japan’s exchange rate falls sharply. How does this affect the price level and real GDP in Japan?

- A wave of pro-German sentiment sweeps France, and the French sharply increase their purchases of German goods and services. How does this affect real GDP and the price level in Germany?

- Canada, the largest importer of U.S. goods and services, slips into a recession. How does this affect the price level and real GDP in the United States?

Case in Point: Canadian Net Exports Survive the Loonie’s Rise

Figure 15.4

Throughout 2003 and the first half of 2004, the Canadian dollar, nicknamed the loonie after the Canadian bird that is featured on its one-dollar coin, rose sharply in value against the U.S. dollar. Because the United States and Canada are major trading partners, the changing exchange rate suggested that, other things equal, Canadian exports to the United States would fall and imports rise. The resulting fall in net exports, other things equal, could slow the rate of growth in Canadian GDP.

Fortunately for Canada, “all other things” were not equal. In particular, strong income growth in the United States and China increased the demand for Canadian exports. In addition, the loonie’s appreciation against other currencies was less dramatic, and so Canadian exports remained competitive in those markets. While imports did increase, as expected due to the exchange rate change, exports grew at a faster rate, and hence net exports increased over the period.

In sum, Canadian net exports grew, although not by as much as they would have had the loonie not appreciated. As Beata Caranci, an economist for Toronto Dominion Bank put it, “We might have some bumpy months ahead but it definitely looks like the worst is over. … While Canadian exports appear to have survived the loonie’s run-up, their fortunes would be much brighter if the exchange rate were still at 65 cents.”

Source: Steven Theobald, “Exports Surviving Loonie’s Rise: Study,” Toronto Star, July 13, 2004, p. D1.

Answers to Try It! Problems

- Mexico’s exports increase, shifting its aggregate demand curve to the right. Mexico’s real GDP and price level rise, as shown in Panel (a).

- Japan’s net exports rise. This event shifts Japan’s aggregate demand curve to the right, increasing its real GDP and price level, as shown in Panel (b).

- Germany’s net exports increase, shifting Germany’s aggregate demand curve to the right, increasing its price level and real GDP, as shown in Panel (c).

- U.S. exports fall, shifting the U.S. aggregate demand curve to the left, which will reduce the price level and real GDP, as shown in Panel (d).

Figure 15.5