This is “Crimes against Property”, chapter 11 from the book Introduction to Criminal Law (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 11 Crimes against Property

Source: Image courtesy of Jane F. Kardashian, MD.

Arson is one of the easiest crimes to commit on the spur of the moment…it takes only seconds to light a match to a pile of clothes or a curtain…

People v. Atkins, cited in Section 11 "Arson Intent"

11.1 Nonviolent Theft Crimes

Learning Objectives

- Define the criminal act element required for consolidated theft statutes.

- Define the criminal intent element required for consolidated theft statutes.

- Define the attendant circumstances required for consolidated theft statutes.

- Define the harm element required for consolidated theft statutes, and distinguish the harm required for larceny theft from the harm required for false pretenses theft.

- Analyze consolidated theft grading.

- Define the elements required for federal mail fraud, and analyze federal mail fraud grading.

Although crimes against the person such as murder and rape are considered extremely heinous, crimes against property can cause enormous loss, suffering, and even personal injury or death. In this section, you review different classifications of nonviolent theft crimes that are called white-collar crimesGenerally refers to nonviolent commercial theft. when they involve commercial theft. Upcoming sections analyze theft crimes that involve force or threat, receiving stolen property, and crimes that invade or damage property, such as burglary and arson. Computer crimes including hacking, identity theft, and intellectual property infringement are explored in an exercise at the end of the chapter.

Consolidated Theft Statutes

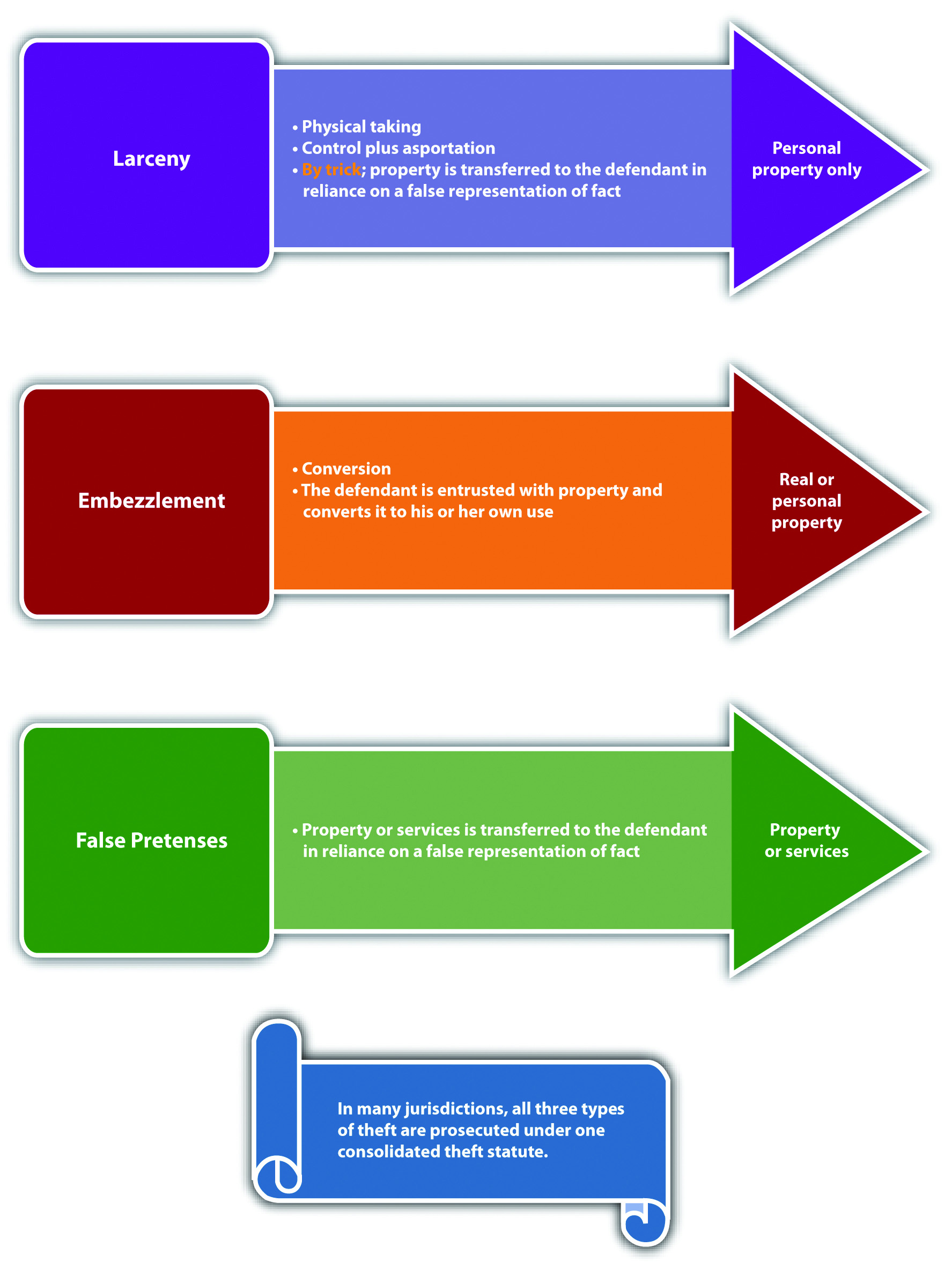

Historically, nonviolent theft was broken down into three categories: larcenyTheft of personal property by a physical taking., embezzlementTheft of real or personal property by conversion., and false pretensesTheft of real property, personal property, or services by a false representation of fact.. The categories differ in the type of property that can be stolen and the method of stealing. Modern jurisdictions combine all three categories of nonviolent theft into one consolidated theft statuteA statute that criminalizes theft by larceny, embezzlement, and false pretenses., with a uniform grading system largely dependent on the value of the stolen property. The Model Penal Code consolidates all nonviolent theft offenses, including receiving stolen property and extortion, under one grading system (Model Penal Code § 223.1). What follows is a discussion of theft as defined in modern consolidated theft statutes, making note of the traditional distinctions among the various theft categories when appropriate. Theft has the elements of criminal act, criminal intent, attendant circumstances, causation, and harm, as is discussed in this chapter.

Consolidated Theft Act

The criminal act element required under consolidated theft statutes is stealing real propertyLand and anything permanently attached to it., personal propertyMovable objects., or services. Real property is land and anything permanently attached to land, like a building. Personal property is any movable item. Personal property can be tangible propertyProperty that can be touched or held., like money, jewelry, vehicles, electronics, cellular telephones, and clothing. Personal property can also be intangible propertyProperty that has value but cannot be touched or held, for example, stocks and bonds., which means it has value, but it cannot be touched or held, like stocks and bonds. The Model Penal Code criminalizes theft by unlawful taking of movable property, theft by deception, theft of services, and theft by failure to make required disposition of funds received under one consolidated grading provision (Model Penal Code §§ 223.1, 223.2, 223.3, 223.7, 223.8).

The act of stealing can be carried out in more than one way. When the defendant steals by a physical taking, the theft is generally a larceny theft. The act of taking is twofold. First, the defendant must gain control over the item. Then the defendant must move the item, which is called asportation, as it is with kidnapping.Britt v. Commonwealth, 667 S.E.2d 763 (2008), accessed March 8, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=2834311189194937383&q= larceny+asportation&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=1999. Although asportation for kidnapping must be a certain distance in many jurisdictions, the asportation for larceny can be any distance—even the slightest motion is sufficient.Britt v. Commonwealth, 667 S.E.2d 763 (2008), accessed March 8, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=2834311189194937383&q= larceny+asportation&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=1999. Control plus asportation can be accomplished by the defendant’s physical act or by deceiving the victim into transferring the property with a false representation of fact. This is called larceny by trickTheft committed by a false representation of fact that results in the defendant’s possession of the stolen personal property.. Because larceny requires a physical taking, it generally only pertains to personal property.

Another way for a defendant to steal property is to convert it to the defendant’s use or ownership. Conversion generally occurs when the victim transfers possession of the property to the defendant, and the defendant thereafter appropriates the property transferred. When the defendant steals by conversion, the theft is generally an embezzlement theft.Commonwealth v. Mills, 436 Mass. 387 (2002), accessed March 7, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=14428947695245966729&q= larceny+false+pretenses+embezzlement&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=1997. Embezzlement could occur when the defendant gains possession of property from a friendship or a family relationship or from a paid relationship such as employer-employee or attorney-client. Embezzlement does not require a physical taking, so it can pertain to real or personal property.

When the defendant steals by a false representation of fact, and the subject of the theft is a service, the theft is generally a false pretenses theft.Cal. Penal Code § 484(a), accessed March 8, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/california/penal/484.html. False pretenses can also be used to steal personal or real property and is very similar to larceny by trick in this regard. What differentiates false pretenses from larceny by trick is the status of the property after it is stolen, which is discussed under the harm element of consolidated theft statutes.

To summarize, whether the defendant steals by a physical taking, a conversion, or a false representation of fact, and whether the defendant steals real or personal property or a service, the crime is theft under modern consolidated theft statutes and is graded primarily on the value of the property or service stolen.

Example of Consolidated Theft Act

Jeremy stops by the local convenience store on his way to work and buys some cigarettes. Before paying for the cigarettes, Jeremy slips a package of chewing gum into his pocket and does not pay for it. Jeremy continues walking to his job at a local gas station. When one of the customers buys gas, Jeremy only rings him up for half of the amount purchased. Once the gas station closes, Jeremy takes the other half out of the cash register and puts it in his pocket with the chewing gum. After work, Jeremy decides to have a drink at a nearby bar. While enjoying his drink, he meets a patron named Chuck, who is a taxi driver. Chuck mentions that his taxi needs a tune-up. Jeremy offers to take Chuck back to the gas station and do the tune-up in exchange for a taxi ride home. Chuck eagerly agrees. The two drive to the gas station, and Jeremy suggests that Chuck take a walk around the block while he performs the tune-up. While Chuck is gone, Jeremy lifts the hood of the taxi and then proceeds to read a magazine. When Chuck returns twenty-five minutes later, Jeremy tells him the tune-up is complete. Chuck thereafter drives Jeremy home for free.

In this scenario, Jeremy has performed three separate acts of theft. When Jeremy slips the package of chewing gum into his pocket without paying for it, he has physically taken personal property, which is a larceny theft. When Jeremy fails to ring up the entire sale for a customer and pockets the rest from the cash register, he has converted the owner of the gas station’s cash for his own use, which is an embezzlement theft. When Jeremy falsely represents to Chuck that he has performed a tune-up of Chuck’s taxi and receives a free taxi ride in payment, he has falsely represented a fact in exchange for a service, which is a false pretenses theft. All three of these acts of theft could be prosecuted under one consolidated theft statute. The three stolen items have a relatively low value, so these crimes would probably be graded as a misdemeanor. Grading of theft under consolidated theft statutes is discussed shortly.

Figure 11.1 Diagram of Consolidated Theft Act

Consolidated Theft Intent

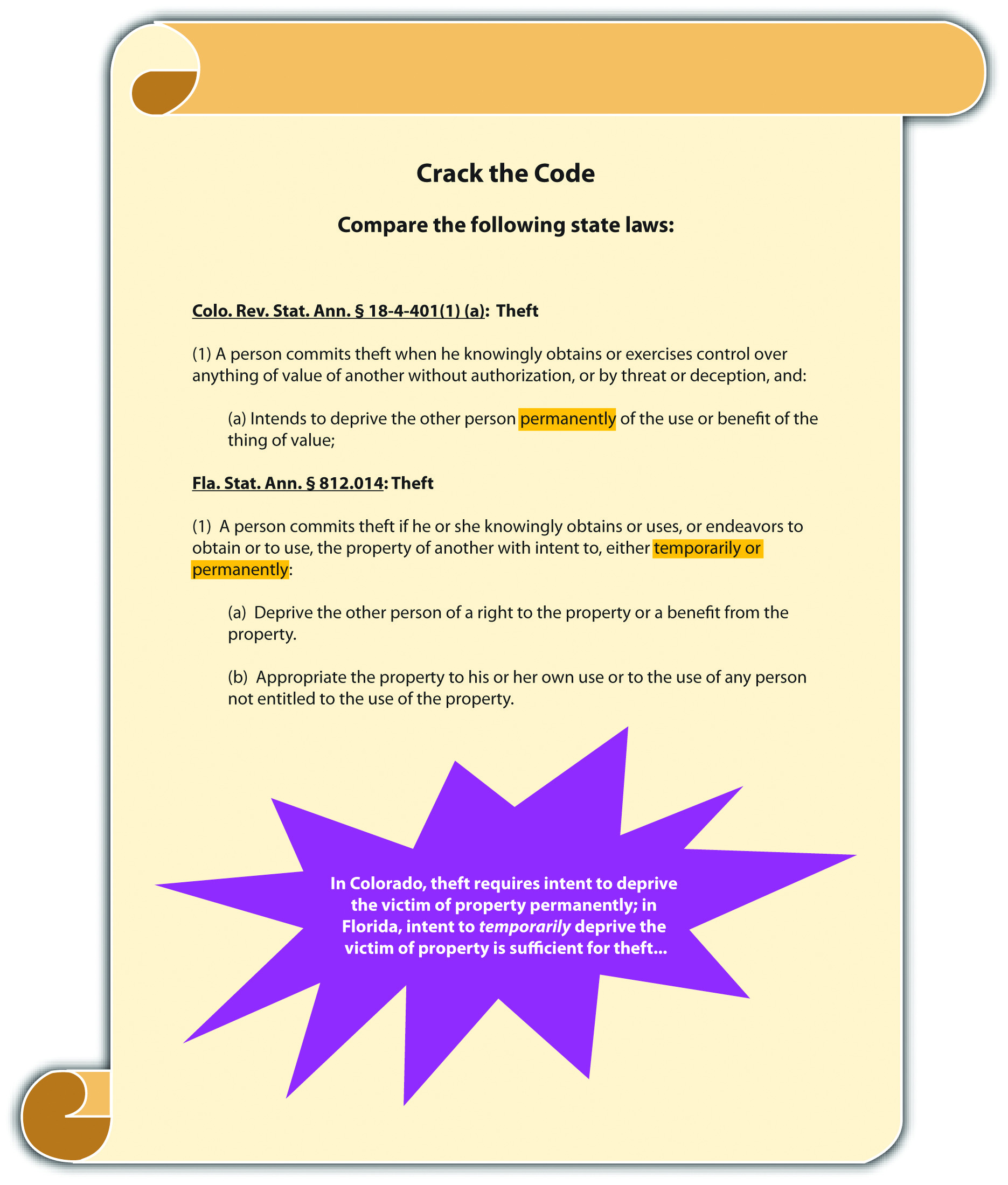

The criminal intent element required under consolidated theft statutes is either specific intent or purposely, or general intent or knowingly to perform the criminal act, depending on the jurisdiction. The Model Penal Code requires purposeful intent for theft by unlawful taking, deception, theft of services, and theft by failure to make required disposition of funds received (Model Penal Code §§ 223.2, 223.3, 223.7, 223.8).

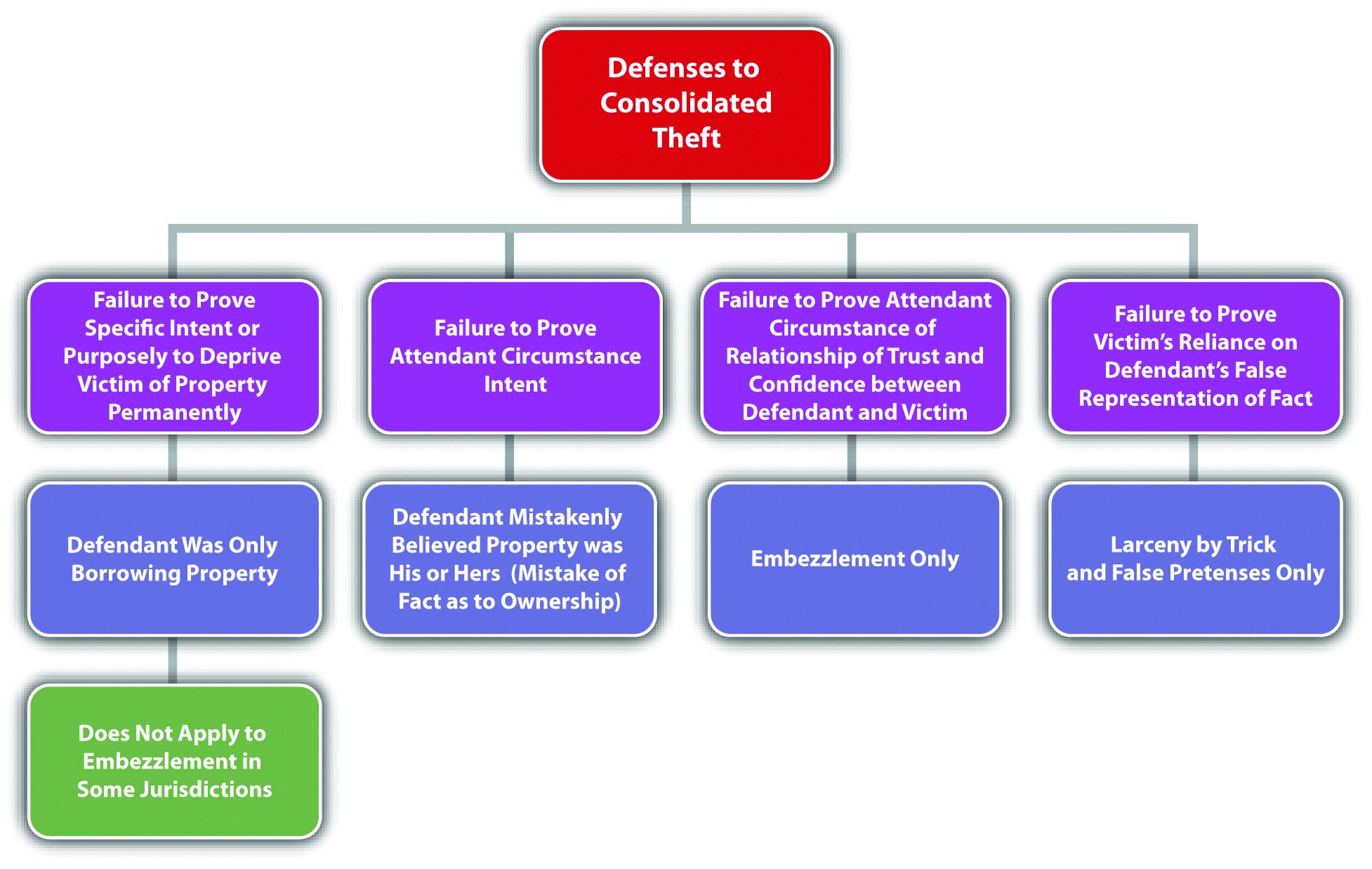

When the criminal intent is specific or purposely, the defendant must intend the criminal act of stealing and must also intend to keep the stolen property.Itin v. Ungar, 17 P.3d 129 (2000), accessed March 8, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=12387802565107699365&q=theft+requires+ specific+intent+to+permanently+deprive&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=1999. This could create a potential failure of proof or affirmative defense that the defendant was only “borrowing” property and intended to return it after use. In some jurisdictions, specific or purposeful intent to keep the property does not apply to embezzlement theft under the traditional definition.In the Matter of Schwimmer, 108 P.3d 761 (2005), accessed March 8, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=637183228950627584&q= embezzlement+borrowing+%22no+intent+to+permanently+deprive%22&hl= en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=1999. Thus in these jurisdictions, a defendant who embezzles property and later replaces it cannot use this replacement as a defense.

Example of a Case Lacking Consolidated Theft Intent

Jorge goes to the nursery and spends hundreds of dollars on plants for his garden. Some of the plants are delicate and must be put into the ground immediately after purchase. When Jorge gets home, he discovers that he has no shovel because he loaned it to his brother-in-law a few weeks ago. He notices that his neighbor’s shovel is leaning against his neighbor’s garage. If Jorge borrows his neighbor’s shovel so that he can get his expensive plants into the ground, this appropriation would probably not constitute the crime of theft under a consolidated theft statute in certain jurisdictions. Jorge had the intent to perform the theft act of taking personal property. However, Jorge did not have the specific or purposeful intent to deprive his neighbor of the shovel permanently, which is often required for larceny theft. Thus in this scenario, Jorge may not be charged with and convicted of a consolidated theft offense.

Example of Consolidated Theft Intent

Review the example with Jeremy given in Section 11 "Example of Consolidated Theft Act". Change this example and assume when Jeremy charged his customer for half of the sale and later pocketed fifty dollars from the cash register, his intent was to borrow this fifty dollars to drink at the bar and replace the fifty dollars the next day when he got paid. Jeremy probably has the criminal intent required for theft under a consolidated theft statute in many jurisdictions. Although Jeremy did not have the specific or purposeful intent to permanently deprive the gas station owner of fifty dollars, this is not generally required with embezzlement theft, which is the type of theft Jeremy committed. Jeremy had the intent to convert the fifty dollars to his own use, so the fact that the conversion was only a temporary deprivation may not operate as a defense, and Jeremy may be charged with and convicted of theft under a consolidated theft statute.

Figure 11.2 Crack the Code

Larceny or False Pretenses Intent as to the False Statement of Fact

As stated previously, the taking in both larceny by trick and false pretenses occurs when the defendant makes a false representation of fact that induces the victim to transfer the property or services. In many jurisdictions, the defendant must have general intent or knowledge that the representation of fact is false and must make the false representation with the specific intent or purposely to deceive.People v. Lueth, 660 N.W.2d 322 (2002), accessed March 9, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=16580779180424536816&q= false+pretenses+knowledge+statement+is+false+intent+to+deceive&hl= en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=1999. The Model Penal Code criminalizes theft by deception when a defendant purposely “creates or reinforces a false impression, including false impressions as to law, value, intention or other state of mind” (Model Penal Code § 223.3(1)).

Example of Larceny or False Pretenses Intent as to the False Representation of Fact

Review the example with Jeremy in Section 11 "Example of Consolidated Theft Act". In this example, Jeremy told Chuck that he performed a tune-up of Chuck’s taxi, when actually he just lifted the hood of the taxi and read a magazine. Because Jeremy knew the representation was false, and made the representation with the intent to deceive Chuck into providing him with a free taxi ride home, Jeremy probably has the appropriate intent for theft of a service by false pretenses, and he may be subject to prosecution for and conviction of this offense under a consolidated theft statute.

Consolidated Theft Attendant Circumstance of Victim Ownership

All theft requires the attendant circumstance that the property stolen is the property of another.Alaska Stat. § 11.46.100, accessed March 8, 2011, http://law.justia.com/codes/alaska/2009/title-11/chapter-11-46/article-01/sec-11-46-100. The criminal intent element for theft must support this attendant circumstance element. Thus mistake of fact or law as to the ownership of the property stolen could operate as a failure of proof or affirmative defense to theft under consolidated theft statutes in many jurisdictions.Haw. Rev. Stat. § 708-834, accessed March 8, 2011, http://law.justia.com/codes/hawaii/2009/volume-14/title-37/chapter-708/hrs-0708-0834-htm. The Model Penal Code provides an affirmative defense to prosecution for theft when the defendant “is unaware that the property or service was that of another” (Model Penal Code § 223.1(3) (a)).

Example of Mistake of Fact as a Defense to Consolidated Theft

Review the example of a case lacking consolidated theft intent given in Section 11 "Example of a Case Lacking Consolidated Theft Intent". Change this example so that Jorge arrives home from the nursery and begins frantically searching for his shovel in his toolshed. When he fails to locate it, he emerges from the shed and notices the shovel leaning against his neighbor’s garage. Jorge retrieves the shovel, uses it to put his plants into the ground, and then puts it into his toolshed and locks the door. If the shovel Jorge appropriated is actually his neighbor’s shovel, which is an exact replica of Jorge’s, Jorge may be able to use mistake of fact as a defense to theft under a consolidated theft statute. Jorge took the shovel, but he mistakenly believed that it was his, not the property of another. Thus the criminal intent for the attendant circumstance of victim ownership is lacking, and Jorge probably will not be charged with and convicted of theft under a consolidated theft statute.

Consolidated Theft Attendant Circumstance of Lack of Consent

Theft under a consolidated theft statute also typically requires the attendant circumstance element of lack of victim consent.Tex. Penal Code § 31.03(b) (1), accessed March 8, 2011, http://law.justia.com/codes/texas/2009/penal-code/title-7-offenses-against-property/chapter-31-theft. Thus victim consent to the taking or conversion may operate as a failure of proof or affirmative defense in many jurisdictions. Keep in mind that all the rules of consent discussed in Chapter 5 "Criminal Defenses, Part 1" and Chapter 10 "Sex Offenses and Crimes Involving Force, Fear, and Physical Restraint" apply. Thus consent obtained fraudulently, as in larceny by trick or false pretenses, is not valid and effective and cannot form the basis of a consent defense.

Example of a Consensual Conversion That Is Noncriminal

Review the example given in Section 11 "Example of Consolidated Theft Act" with Jeremy. Change the example so that the owner of the gas station is Jeremy’s best friend Cody. Cody tells Jeremy several times that if he is ever short of cash, he can simply take some cash from the register, as long as it is not more than fifty dollars. Assume that on the date in question, Jeremy did not ring up half of a sale but simply took fifty dollars from the register because he was short on cash, and he needed money to order drinks at the bar. In this case, Jeremy may have a valid defense of victim’s consent to any charge of theft under a consolidated theft statute.

Embezzlement Attendant Circumstance of a Relationship of Trust and Confidence

In many jurisdictions, embezzlement theft under a consolidated theft statute requires the attendant circumstance element of a relationship of trust and confidence between the victim and the defendant.Commonwealth v. Mills, 436 Mass. 387 (2002), accessed March 7, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=14428947695245966729&q= larceny+false+pretenses+embezzlement&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=1997. This relationship is generally present in an employer-employee relationship, a friendship, or a relationship where the defendant is paid to care for the victim’s property. However, if the attendant circumstance element of trust and confidence is lacking, the defendant will not be subject to prosecution for embezzlement under a consolidated theft statute in many jurisdictions.

Example of a Case Lacking Embezzlement Attendant Circumstance

Tran sells an automobile to Lee. Tran’s automobile has personalized license plates, so he offers to apply for new license plates and thereafter send them to Lee. Lee agrees and pays Tran for half of the automobile, the second payment to be made in a week. Lee is allowed to take possession of the automobile and drives it to her home that is over one hundred miles away. Tran never receives the second payment from Lee. When the new license plates arrive, Tran phones Lee and tells her he is going to keep them until Lee makes her second payment. In some jurisdictions, Tran has not embezzled the license plates. Although Tran and Lee have a relationship, it is not a relationship based on trust or confidence. Tran and Lee have what is called a debtor-creditor relationship (Lee is the debtor and Tran is the creditor). Thus if the jurisdiction in which Tran sold the car requires a special confidential relationship for embezzlement, Tran may not be subject to prosecution for this offense.

Attendant Circumstance of Victim Reliance Required for False Pretenses or Larceny by Trick

A false pretenses or larceny by trick theft under a consolidated theft statute requires the additional attendant circumstance element of victim reliance on the false representation of fact made by the defendant.People v. Lueth, 660 N.W.2d 332 (2002), accessed March 9, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=16580779180424536816&q= false+pretenses+knowledge+statement+is+false+intent+to+deceive&hl= en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=1999. Thus a victim’s knowledge that the statement is false could operate as a failure of proof or affirmative defense in many jurisdictions.

Example of a Case Lacking the Attendant Circumstance of Victim Reliance Required for False Pretenses

Review the example with Jeremy and Chuck in Section 11 "Example of Consolidated Theft Act". Change the example so that Chuck does not walk around the block as Jeremy asked him to do. Instead, Chuck walks around the corner and then spies on Jeremy while he reads a magazine with the hood open. Chuck takes out his phone and makes a videotape of Jeremy. After twenty-five minutes, Chuck walks back over to Jeremy and thereafter gives Jeremy the free taxi ride home. When they arrive at Jeremy’s house, Chuck shows Jeremy the videotape and threatens to turn it over to the district attorney if Jeremy does not pay him two hundred dollars. In this case, Jeremy probably has a valid defense to false pretenses theft. Chuck, the “victim,” did not rely on Jeremy’s false representation of fact. Thus the attendant circumstance element of false pretenses is lacking and Jeremy may not be subject to prosecution for and conviction of this offense. Keep in mind that this is a false pretenses scenario because Chuck gave Jeremy a service, and larceny by trick only applies to personal property. Also note that Chuck’s action in threatening Jeremy so that Jeremy will pay him two hundred dollars may be the criminal act element of extortion, which is discussed shortly.

Figure 11.3 Diagram of Defenses to Consolidated Theft

Consolidated Theft Causation

The criminal act must be the factual and legal cause of the consolidated theft harm, which is defined in Section 11 "Consolidated Theft Harm".

Consolidated Theft Harm

Consolidated theft is a crime that always includes bad results or harm, which is the victim’s temporary or permanent loss of property or services, no matter how slight the value. In the case of theft by false pretenses and larceny by trick, in some jurisdictions, the status of the property after it has been stolen determines which crime was committed. If the defendant becomes the owner of the stolen property, the crime is a false pretenses theft.People v. Curtin, 22 Cal. App. 4th 528 (1994), accessed March 10, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=3765672039191216315&q= false+pretenses+theft+of+a+service&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=1999. If the defendant is merely in possession of the stolen property, the crime is larceny by trick.People v. Beaver, 186 Cal. App. 4th 107 (2010), accessed March 10, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=12194560873043980150&q= false+pretenses+theft+of+a+service&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=1999. When the stolen property is money, the crime is false pretenses theft because the possessor of money is generally the owner.People v. Curtin, 22 Cal. App. 4th 528 (1994), accessed March 10, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=3765672039191216315&q= false+pretenses+theft+of+a+service&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=1999.

Example of False Pretenses Theft Harm

Review the example given in Section 11 "Example of a Case Lacking Embezzlement Attendant Circumstance" with Tran and Lee. In this example, Lee paid Tran half of the money she owed him for his vehicle, with a promise to pay the remainder in one week. Assume that Lee never intended to pay the second installment when she made the deal with Tran. Tran signs the ownership documents over to Lee, promises to send Lee the license plates when they arrive, and watches as Lee drives off, never to be seen again. In this example, Lee has most likely committed false pretenses theft, rather than larceny by trick. Lee made a false representation of fact with the intent to deceive and received a vehicle for half price in exchange. The vehicle belongs to Lee, and the ownership documents are in her name. Thus Lee has ownership of the stolen vehicle rather than possession, and the appropriate offense is false pretenses theft.

Example of Larceny by Trick Harm

Jacob, a car thief, runs up to Nanette, who is sitting in her Mercedes with the engine running. Jacob tells Nanette he is a law enforcement officer and needs to take control of her vehicle to pursue a fleeing felon. Nanette skeptically asks Jacob for identification. Jacob pulls out a phony police badge and says, “Madam, I hate to be rude, but if you don’t let me drive your vehicle, a serial killer will be roaming the streets looking for victims!” Nanette grudgingly gets out of the car and lets Jacob drive off, never to be seen again. In this example, Jacob has obtained the Mercedes, but the ownership documents are still in Nanette’s name. Thus Jacob has possession of the stolen vehicle rather than ownership, and the appropriate offense is larceny by trick.

Consolidated Theft Grading

Grading under consolidated theft statutes depends primarily on the value of the stolen property. Theft can be graded by degreesConnecticut Jury Instructions §§ 53a-119, 53a-122 through 53a-125b, accessed March 10, 2011, http://www.jud.ct.gov/JI/criminal/part9/9.1-1.htm. or as petty theftTheft of low-value property., which is theft of property with low value, and grand theftTheft of high-value property., which is theft of property with significant value.Cal. Penal Code § 486, accessed March 10, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/california/penal/486.html. Petty theft or theft of the second or third degree is generally a misdemeanor, while grand theft or theft of the first degree is generally a felony, felony-misdemeanor, or gross misdemeanor, depending on the amount stolen or whether the item stolen is a firearm.Cal. Penal Code § 489, accessed March 10, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/california/penal/489.html. The Model Penal Code grades theft as a felony of the third degree if the amount stolen exceeds five hundred dollars or if the property stolen is a firearm, automobile, airplane, motorcycle, or other motor-propelled vehicle (Model Penal Code § 223.1(2)). The Model Penal Code grades all other theft as a misdemeanor or petty misdemeanor (Model Penal Code § 223.1(2)). When determining the value of property for theft, in many jurisdictions, the value is market value, and items can be aggregated if they were stolen as part of a single course of conduct.Connecticut Jury Instructions §§ 53a-119, 53a-122 through 53a-125b, accessed March 10, 2011, http://www.jud.ct.gov/JI/criminal/part9/9.1-1.htm. The Model Penal Code provides that “[t]he amount involved in a theft shall be deemed to be the highest value, by any reasonable standard…[a]mounts involved in thefts committed pursuant to one scheme or course of conduct, whether from the same person or several persons, may be aggregated in determining the grade or the offense” (Model Penal Code § 223.1(2) (c)).

Table 11.1 Comparing Larceny, Larceny by Trick, False Pretenses, and Embezzlement

| Crime | Criminal Act | Type of Property | Criminal Intent | Attendant Circumstance | Harm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Larceny | Taking control plus asportation | Personal | Specific or purposely to deprive victim permanently* | Victim’s property (applies to all four theft crimes), lack of victim consent | Property loss |

| Larceny by trick | Taking by a false representation of fact | Personal | Specific or purposely to deceive* | Victim reliance on false representation | Victim loses possession of property |

| False pretenses | Taking by a false representation of fact | Personal, real, services | Specific or purposely to deceive* | Victim reliance on false representation | Victim loses ownership of property |

| Embezzlement | Conversion | Personal, real | Specific or purposely to deprive victim temporarily or permanently* | Relationship of trust and confidence between defendant and victim (some jurisdictions) | Property loss either temporary or permanent |

| *Some jurisdictions include general intent or knowingly to commit the criminal act. | |||||

| Note: Grading under consolidated theft statutes is based primarily on property value; market value is the standard, and property can be aggregated if stolen in a single course of conduct. | |||||

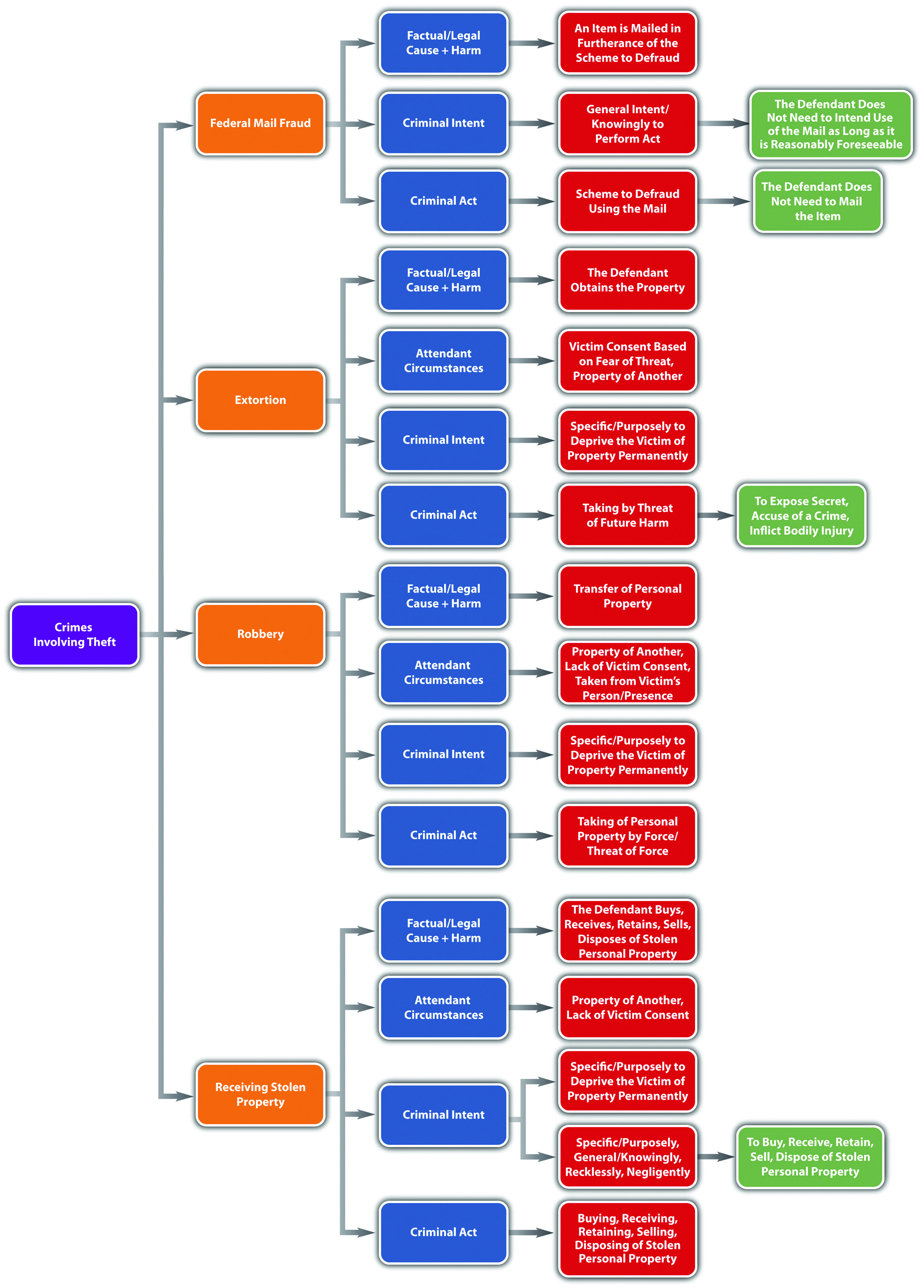

Federal Mail Fraud

The federal government criminalizes theft by use of the federal postal service as federal mail fraudA scheme to defraud that utilizes the US Postal Service., a felony.18 U.S.C. § 1341, accessed March 18, 2011, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/18/usc_sec_18_00001341----000-.html. Like every federal offense, federal mail fraud is criminal in all fifty states. In addition, a defendant can be prosecuted by the federal and state government for one act of theft without violating the double jeopardy protection in the Fifth Amendment of the federal Constitution.

The criminal act element required for federal mail fraud is perpetrating a “scheme to defraud” using the US mail.18 U.S.C. § 1341, accessed March 18, 2011, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/18/usc_sec_18_00001341----000-.html. Scheme has been given a broad interpretation and includes “everything designed to defraud by representations as to the past or present, or suggestions and promises as to the future.”Durland v. U.S., 161 U.S. 306, 313 (1896), http://supreme.justia.com/us/161/306. Even one act of mailing is sufficient to subject the defendant to a criminal prosecution for this offense.U.S. v. McClelland, 868 F.2d 704 (1989), accessed March 18, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=8428034080210339517&q= federal+mail+fraud+%22one+letter%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=2000. In addition, the defendant does not need to actually mail anything himself or herself.U.S. v. McClelland, 868 F.2d 704 (1989), accessed March 18, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=8428034080210339517&q= federal+mail+fraud+%22one+letter%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=2000. The criminal intent element required for federal mail fraud is general intent or knowingly or awareness that the mail will be used to further the scheme.U.S. v. McClelland, 868 F.2d 704 (1989), accessed March 18, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=8428034080210339517&q= federal+mail+fraud+%22one+letter%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=2000. The defendant does not have to intend that the US Mail will be used to commit the theft, as long as use of the postal service is reasonably foreseeable in the ordinary course of business.U.S. v. McClelland, 868 F.2d 704 (1989), accessed March 18, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=8428034080210339517&q= federal+mail+fraud+%22one+letter%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=2000. The defendant’s criminal act, supported by the appropriate intent, must be the factual and legal cause of the harm, which is the placement of anything in any post office or depository to be sent by the US Postal Service in furtherance of the scheme to defraud.18 U.S.C. § 1341, accessed March 18, 2011, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/18/usc_sec_18_00001341----000-.html.

The Mail Fraud Act has been used to punish a wide variety of schemes, including Ponzi schemesA scheme where the defendant appropriates investments unlawfully and pays investors by using money from new investors., like the recent high-profile Bernie Madoff case.Constance Parten, “After Madoff: Notable Ponzi Schemes,” CNBC website, accessed March 11, 2011, http://www.cnbc.com/id/41722418/After_Madoff_Most_Notable_Ponzi_Scams. In a Ponzi scheme, the defendant informs investors that their investment is being used to purchase real estate, stocks, or bonds, when, in actuality, the money is appropriated by the defendant and used to pay earlier investors. Eventually this leads to a collapse that divests all investors of their investment.

Federal statutes also punish bank fraud,18 U.S.C. § 1344, accessed March 11, 2011, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/18/usc_sec_18_00001344----000-.html. health care fraud,18 U.S.C. § 1347, accessed March 11, 2011, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/18/usc_sec_18_00001347----000-.html. securities fraud,18 U.S.C. § 1348, accessed March 11, 2011, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/18/usc_sec_18_00001348----000-.html. and fraud in foreign labor contracting.18 U.S.C. § 1351, accessed March 11, 2011, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/18/usc_sec_18_00001351----000-.html. Fraud committed by wire, television, and radio also is federally criminalized.18 U.S.C. § 1343, accessed March 11, 2011, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/18/usc_sec_18_00001343----000-.html.

Bernard Madoff Video

Bernard Madoff $50 Billion Ponzi Scheme: How Did He Do It?

The facts behind Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme are explained in this video:

Key Takeaways

- The criminal act element required for consolidated theft statutes is stealing real or personal property or services. The defendant can commit the theft by a physical taking (larceny), conversion of property in the defendant’s possession (embezzlement), or a false representation of fact (false pretenses or larceny by trick).

- The criminal intent element required for consolidated theft statutes is either specific intent or purposely, or general intent or knowingly to perform the criminal act, depending on the jurisdiction. When the criminal intent is specific or purposely, the defendant must intend the criminal act of stealing and must also intend to keep the stolen property. For false pretenses or larceny by trick theft, in many jurisdictions the defendant must have general intent or knowledge that the representation of fact is false and must make the false representation with the specific intent or purposely to deceive.

-

All theft generally requires the attendant circumstances that the property stolen is the property of another, and victim consent to the taking, conversion, or transfer of ownership is lacking.

- In many jurisdictions, embezzlement theft under a consolidated theft statute requires the attendant circumstance element of a relationship of trust and confidence between the victim and the defendant.

- A false pretenses or larceny by trick theft under a consolidated theft statute requires the additional attendant circumstance element of victim reliance on the false representation of fact made by the defendant.

- The harm element required for consolidated theft statutes is the victim’s temporary or permanent loss of property or services, no matter how slight the value. When the defendant gains possession of personal property by a false representation of fact, the theft is larceny by trick theft. When the defendant gains ownership of personal property or possession of money, the theft is false pretenses theft.

- Theft can be graded by degrees or as petty theft, which is theft of property with low value, and grand theft, which is theft of property with significant value. Petty theft or theft of the second or third degree is generally a misdemeanor, while grand theft or theft of the first degree is generally a felony, felony-misdemeanor, or gross misdemeanor, depending on the amount stolen or whether the item stolen is a firearm.

- The criminal act element required for federal mail fraud is the use of the federal postal service to further any scheme to defraud. The criminal intent element required for this offense is general intent, knowingly, or awareness that the postal service will be used. The criminal act supported by the criminal intent must be the factual and legal cause of the harm, which is the placement of anything in a depository or postal office that furthers the scheme to defraud. Federal mail fraud is a felony.

Exercises

Answer the following questions. Check your answers using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

- Recall a scenario in Chapter 1 "Introduction to Criminal Law" where Linda and Clara browse an expensive department store’s lingerie department and Linda surreptitiously places a bra in her purse and leaves the store without paying for it. What type of theft did Linda commit in this scenario?

- Ellen goes to the fine jewelry department at Macy’s and asks the clerk if she can see a Rolex watch, valued at ten thousand dollars. The clerk takes the watch out of the case and lays it on the counter. Ellen tells the clerk that her manager is signaling. When the clerk turns around, Ellen puts her hand over the watch and begins to slide it across the counter and into her open purse. Before the watch slides off the counter, the clerk turns back around and pins Ellen’s hand to the counter, shouting for a security guard. Has Ellen committed a crime in this scenario? If your answer is yes, which crime?

- Read State v. Larson, 605 N.W. 2d 706 (2000). In Larson, the defendant, the owner of an automobile leasing company, was convicted of theft by temporary taking under a consolidated theft statute for failing to return security deposits to customers pursuant to their automobile lease contracts. The defendant appealed, claiming that the lease deposits were not the “property of another.” Did the Supreme Court of Minnesota uphold the defendant’s conviction? Why or why not? The case is available at this link: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=18374046737925458759&q= embezzlement+%22temporary+taking%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5.

- Read People v. Traster, 111 Cal. App. 4th 1377 (2003). In Traster, the defendant told his employer that it was necessary to purchase computer-licensing agreements, and he was given the employer credit card to purchase them. The defendant thereafter appropriated the money, never purchased the licenses, and quit his job a few days later. The defendant was convicted of theft by false pretenses under a consolidated theft statute. Did the Court of Appeal of California uphold the defendant’s conviction? Why or why not? The case is available at this link: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=14111729725043843748&q= larceny+false+pretenses+possession+ownership&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=2000.

- Read U.S. v. Ingles, 445 F.3d 830 (2006). In Ingles, the defendant was convicted of federal mail fraud when his son’s cabin was burned by arson and his son made a claim for homeowner’s insurance. The evidence indicated that the defendant was involved in the arson. The defendant’s son was acquitted of the arson, and only the insurance company, which sent several letters to the defendant’s son, did the acts of mailing. Did the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit uphold the defendant’s conviction? Why or why not? The case is available at this link: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=6621847677802005327&q= federal+mail+fraud+%22one+letter%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=2000.

11.2 Extortion, Robbery, and Receiving Stolen Property

Learning Objectives

- Define the criminal act element required for extortion.

- Define the criminal intent element required for extortion.

- Identify a potential defense to extortion.

- Define the attendant circumstances required for extortion.

- Define the harm element required for extortion.

- Analyze extortion grading.

- Identify the differences between robbery, larceny, and extortion.

- Analyze robbery grading.

- Define the criminal act element required for receiving stolen property.

- Define the criminal intent element required for receiving stolen property.

- Identify a failure of proof or affirmative defense to receiving stolen property in some jurisdictions.

- Define the attendant circumstances and harm element required for receiving stolen property.

- Analyze receiving stolen property grading.

Extortion

All states and the federal government criminalize extortionTheft by a threat of future harm., which is also called blackmail.K.S.A. § 21-3428, accessed March 18, 2011, http://kansasstatutes.lesterama.org/Chapter_21/Article_34/21-3428.html. As stated previously, the Model Penal Code criminalizes theft by extortion and grades it the same as all other nonforcible theft offenses (Model Penal Code § 223.4). Extortion is typically nonviolent, but the elements of extortion are very similar to robbery, which is considered a forcible theft offense. Robbery is discussed shortly.

Extortion has the elements of criminal act, criminal intent, attendant circumstances, causation, and harm, as is explored in Section 11.2.1 "Extortion".

Extortion Act

The criminal act element required for extortion is typically the theft of property accomplished by a threat to cause future harm to the victim, including the threat to inflict bodily injury, accuse anyone of committing a crime, or reveal a secret that would expose the victim to hatred, contempt, or ridicule.Ga. Code § 16-8-16, accessed March 11, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/georgia/16/16-8-16.html. The Model Penal Code criminalizes theft by extortion when the defendant obtains property of another by threatening to inflict bodily injury on anyone, commit any criminal offense, accuse anyone of a criminal offense, expose any secret tending to subject any person to hatred, contempt, or ridicule or impair his credit and business repute, take or withhold action as an official, bring about a strike or boycott, testify with respect to another’s legal claim, or inflict any other harm that would not benefit the actor (Model Penal Code § 223.4). Note that some of these acts could be legal, as long as they are not performed with the unlawful intent to steal.

Example of Extortion Act

Rodney tells Lindsey that he will report her illegal drug trafficking to local law enforcement if she does not pay him fifteen thousand dollars. Rodney has probably committed the criminal act element required for extortion in most jurisdictions. Note that Rodney’s threat to expose Lindsey’s illegal activities is actually desirable behavior when performed with the intent to eliminate or reduce crime. However, under these circumstances, Rodney’s act is most likely criminal because it is supported by the intent to steal fifteen thousand dollars from Lindsey.

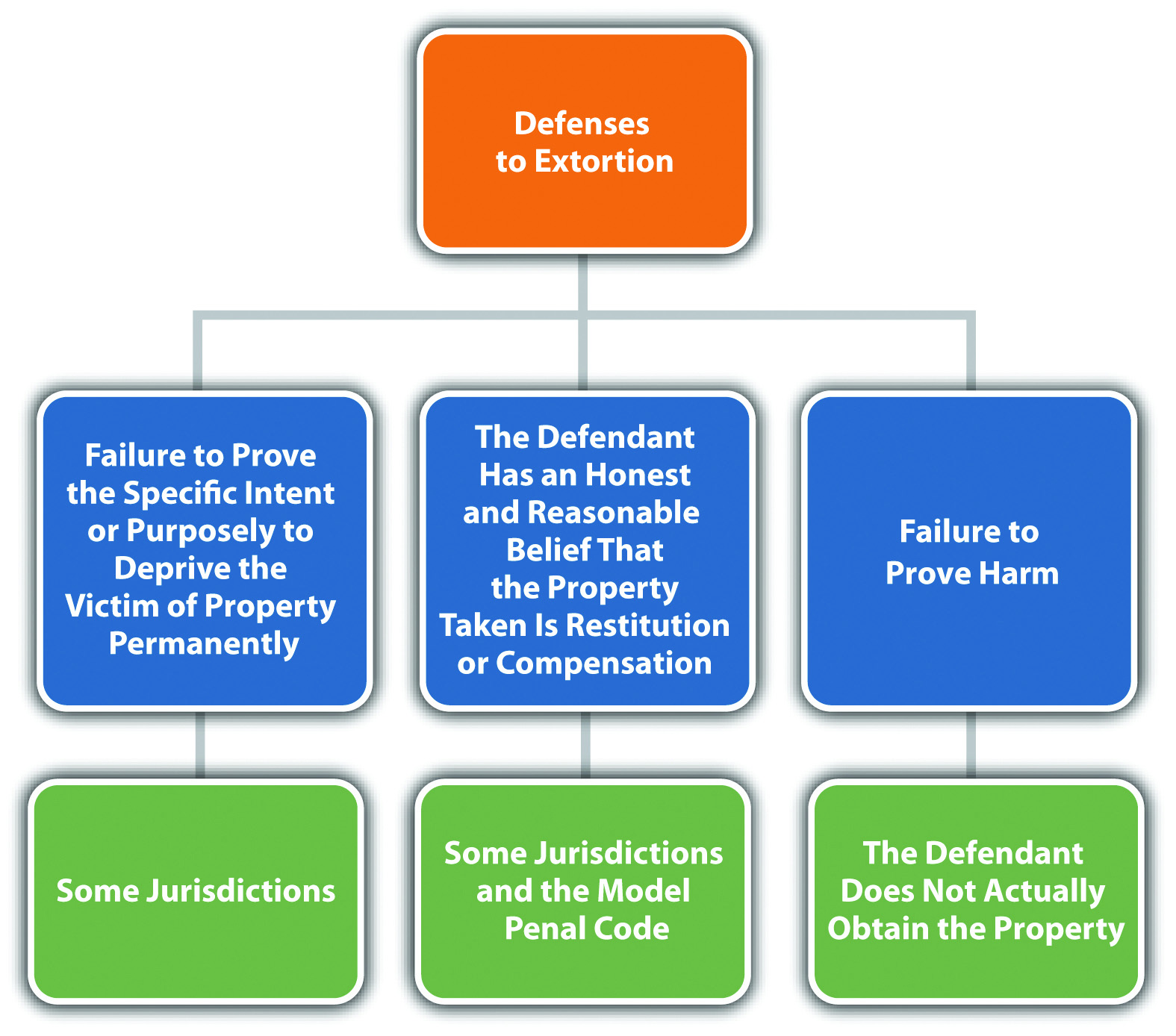

Extortion Intent

The criminal intent element required for extortion is typically the specific intent or purposely to commit the criminal act and to unlawfully deprive the victim of property permanently.Connecticut Criminal Jury Instructions §§53a-119(5) and 53a-122(a) (1), accessed March 12, 2011, http://www.jud.ct.gov/ji/criminal/part9/9.1-11.htm. This intent requirement is similar to the criminal intent element required for larceny and false pretenses theft, as discussed in Section 11 "Consolidated Theft Intent". Some jurisdictions only require general intent or knowingly to perform the criminal act.Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 13-1804, http://law.onecle.com/arizona/criminal-code/13-1804.html.

Example of a Case Lacking Extortion Intent

Review the example with Rodney and Lindsey in Section 11 "Example of Extortion Act". Change the example and assume that Rodney asks Lindsey to loan him the fifteen thousand dollars so that he can make a balloon payment due on his mortgage. Lindsey refuses. Rodney thereafter threatens to expose Lindsey’s drug trafficking if she doesn’t loan him the money. In many jurisdictions, Rodney may not have the criminal intent element required for extortion. Although Rodney performed the criminal act of threatening to report Lindsey for a crime, he did so with the intent to borrow money from Lindsey. Thus Rodney did not act with the specific intent or purposely to permanently deprive Lindsey of property, which could operate as a failure of proof or affirmative defense to extortion in many jurisdictions.

Extortion Attendant Circumstance

Extortion is a form of theft, so it has the same attendant circumstance required in consolidated theft statutes—the property stolen belongs to another. In many jurisdictions, it is an affirmative defense to extortion that the property taken by threat to expose a secret or accuse anyone of a criminal offense is taken honestly, as compensation for property, or restitution or indemnification for harm done by the secret or crime.Ga. Code § 16-8-16, accessed March 11, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/georgia/16/16-8-16.html. The Model Penal Code provides an affirmative defense to extortion by threat of accusation of a criminal offense, exposure of a secret, or threat to take or withhold action as an official if the property obtained was “honestly claimed as restitution or indemnification for harm done in the circumstances to which such accusation, exposure, lawsuit or other official action relates, or as compensation for property or lawful services” (Model Penal Code § 223.4).

Example of Extortion Affirmative Defense

Tara, a real estate broker, hires Trent to be a real estate sales agent in her small realty office. Tara decides she wants to get the property listing of a competitor by using Trent to obtain information. Tara tells Trent to pretend he is a buyer interested in the property. She asks him to make an appointment with the competitor, ask a lot of questions about the owner of the property, and thereafter bring Tara the information. Tara promises to pay Trent one thousand dollars for his time and effort. Trent spends several hours performing this task and thereafter demands his one thousand dollars payment. Tara tells Trent she is experiencing “tough times” and can’t afford to pay him. Trent threatens to tell Tara’s competitor what she is up to if she doesn’t pay him the one thousand dollars. Trent has probably not committed extortion in many jurisdictions. Although Trent threatened to expose Tara’s secret if she didn’t pay him one thousand dollars, Trent honestly believed he was owed this money for a job he performed that was directly related to the secret. Thus in many jurisdictions, Trent has an affirmative defense that the money demanded was compensation for services and not the subject of unlawful theft by extortion.

Attendant Circumstance of Victim Consent

Extortion also requires the attendant circumstance of victim consent. With extortion, the victim consensually transfers the property based on fear inspired by the defendant’s threat.Oklahoma Uniform Jury Instructions No. CR 5-34, accessed March 12, 2011, http://www.okcca.net/online/oujis/oujisrvr.jsp?oc=OUJI-CR%205-34.

Example of Attendant Circumstance of Victim Consent for Extortion

Review the example with Rodney and Lindsey in Section 11 "Example of Extortion Act". Assume that Lindsey grudgingly gives Rodney the fifteen thousand dollars so that he will not report her drug trafficking. In this example, Lindsey is consensually transferring the money to Rodney to prevent him from making good on his threat. Thus the attendant circumstance of victim consent based on fear is most likely present, and Rodney could be subject to prosecution for and conviction of extortion in most jurisdictions.

Extortion Causation

The criminal act must be the factual and legal cause of extortion harm, which is defined in Section 11 "Extortion Harm".

Extortion Harm

The defendant must obtain property belonging to another for the completed crime of extortion in most jurisdictions.Oklahoma Uniform Jury Instructions No. CR 5-34, accessed March 12, 2011, http://www.okcca.net/online/oujis/oujisrvr.jsp?oc=OUJI-CR%205-34. If the defendant commits the criminal act of threatening the victim with the appropriate criminal intent, but the victim does not actually transfer the property to the defendant, the defendant can only be charged with attempted extortion.Oklahoma Uniform Jury Instructions No. CR 5-32, accessed March 12, 2011, http://www.okcca.net/online/oujis/oujisrvr.jsp?oc=OUJI-CR%205-32.

Example of a Case Lacking Extortion Harm

Review the example with Rodney and Lindsey in Section 11 "Example of Extortion Act". Assume that after Rodney threatens to report Lindsey’s drug trafficking to local law enforcement, Lindsey calls local law enforcement, turns herself in for drug trafficking, and also reports Rodney for making the threat. In this case, because Rodney did not “obtain” property by threat, the crime of extortion is not complete, and attempted extortion would be the appropriate charge in most jurisdictions.

Figure 11.4 Diagram of Defenses to Extortion

Extortion Grading

Extortion is generally graded as a felony in most jurisdictions.Or. Rev. Stat. § 164.075, accessed March 12, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/oregon/164-offenses-against-property/164.075.html. As stated previously, the Model Penal Code grades extortion under its consolidated theft offense.

Robbery

RobberyTheft by force or threat of imminent force. was the first common-law theft crime. The criminalization of robbery was a natural progression from other common-law crimes against the person because robbery always involves force, violence, or threat and could pose a risk of injury or death to the robbery victim, defendant, or other innocent bystanders. Recall from Chapter 9 "Criminal Homicide" that robbery is generally a serious felony that is included in most felony murder statutes as a predicate felony for first-degree felony murder. When robbery does not result in death, it is typically graded more severely than theft under a consolidated theft statute. Robbery grading is discussed shortly.

The elements of robbery are very similar to the elements of larceny and extortion. For the purpose of brevity, only the elements of robbery that are distinguishable from larceny and extortion are analyzed in depth. Robbery has the elements of criminal act, attendant circumstances, criminal intent, causation, and harm, as is explored in Section 11.2 "Extortion, Robbery, and Receiving Stolen Property".

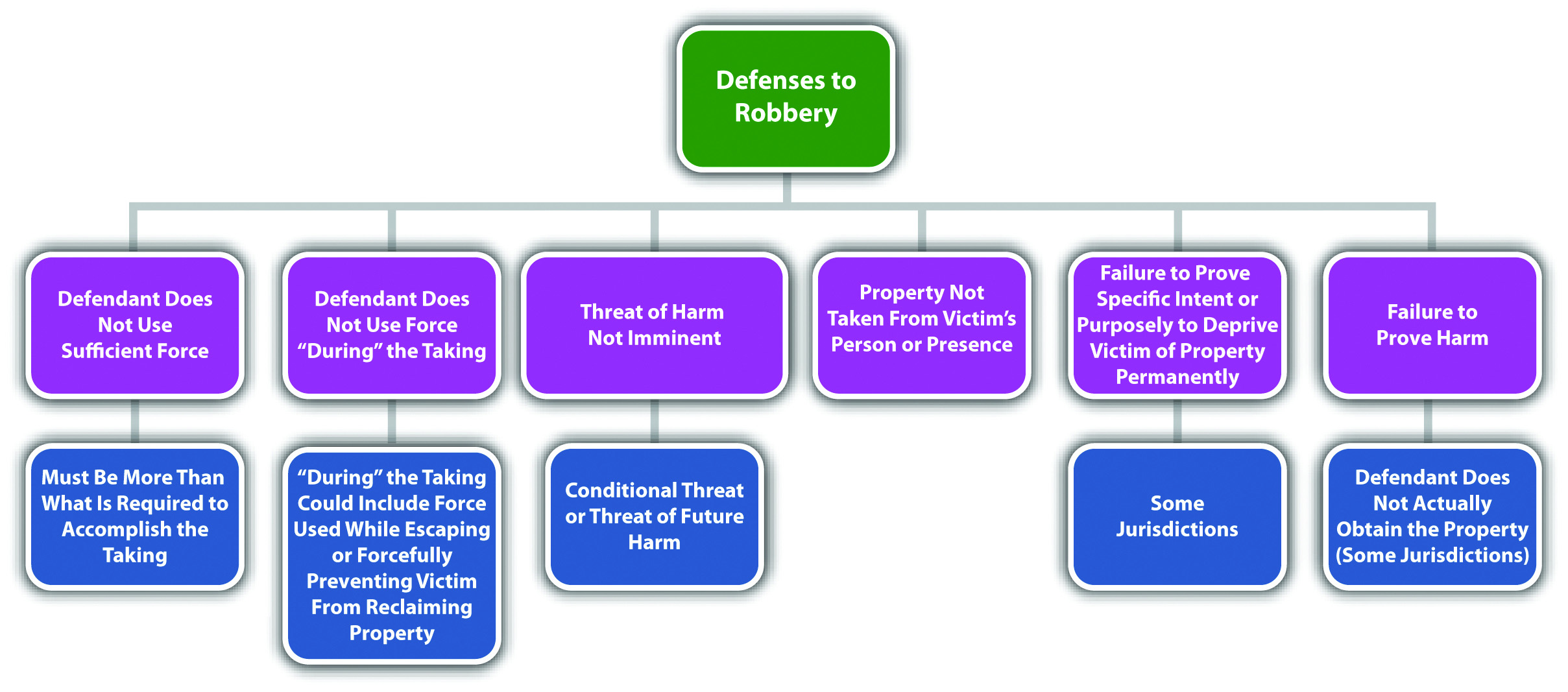

Robbery Act

It is the criminal act element that primarily distinguishes robbery from larceny and extortion. The criminal act element required for robbery is a taking of personal property by force or threat of force.Ind. Code § 35-42-5-1, accessed March 18, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/indiana/35/35-42-5-1.html. Force is generally physical force. The force can be slight, but it must be more than what is required to gain control over and move the property.S.W. v. State, 513 So. 2d 1088 (1987), accessed March 18, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=8956843531832075141&q= robbery+%22slight+force%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5. Many jurisdictions require force during the taking, which includes the use of force to prevent the victim from reclaiming the property, or during escape.State v. Handburgh, 830 P.2d 641 (1992), accessed March 18, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=2186457002998894202&q= State+v.+Handburgh&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5. The Model Penal Code requires force or threat “in the course of committing a theft” and defines this as occurring in “an attempt to commit theft or in flight after the attempt or commission” (Model Penal Code § 222.1(1)). Threat for robbery is a threat to inflict imminent force.Ala. Code § 13A-8-43, accessed March 18, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/alabama/criminal-code/13A-8-43.html.

While larceny and extortion also require a taking, the defendant typically accomplishes the larceny taking by stealth, or a false representation of fact. In extortion, the defendant accomplishes the taking by a threat of future harm that may or may not involve force.

Example of Robbery Act

Review the example given in Section 11 "Example of Extortion Act" with Rodney and Lindsey. In this example, Rodney threatened to expose Lindsey’s drug trafficking if she didn’t pay him fifteen thousand dollars. Change the example so that Rodney tells Lindsey he will kill her if she doesn’t write him a check for fifteen thousand dollars. Rodney exemplifies his threat by pointing to a bulge in his front jacket pocket that appears to be a weapon. In this scenario, Rodney has most likely committed the criminal act element required for robbery, not extortion. Rodney’s threat is a threat of immediate force. Compare this threat to Rodney’s threat to expose Lindsey’s drug trafficking, which is a threat of future harm that relates to Lindsey’s arrest for a crime, rather than force.

Example of a Case Lacking Robbery Act

Peter, a jewelry thief, notices that Cheryl is wearing a diamond ring. Peter walks up to Cheryl and asks her if she wants him to read her palm. Cheryl shrugs her shoulders and says, “Sure! What have I got to lose?” While Peter does an elaborate palm reading, he surreptitiously slips Cheryl’s diamond ring off her finger and into his pocket. Peter has probably not committed the criminal act element required for robbery in this case. Although Peter used a certain amount of physical force to remove Cheryl’s ring, he did not use any force beyond what was required to gain control over Cheryl’s property and move it into his possession. Thus Peter has probably committed the criminal act element required for larceny theft, not robbery, and is subject to less severe sentencing for this lower-level offense.

Robbery Attendant Circumstances

Another difference between robbery and larceny or extortion is the attendant circumstances requirement(s). Robbery requires the same attendant circumstance required for both larceny and extortion—that the property taken belongs to another. It also has the same attendant circumstance as larceny—that the defendant accomplish the taking against the victim’s will and without consent. However, robbery has one additional attendant circumstance, which is that the property be taken from the victim’s person or presence.Cal. Penal Code § 211, accessed March 19, 2011, http://codes.lp.findlaw.com/cacode/PEN/3/1/8/4/s211. The property does not need to be in the actual physical possession of the victim, as long as it is under the victim’s control.Jones v. State, 652 So. 2d 346 (1995), accessed March 19, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=11856873917512077763&q= robbery+%22from+the+victim%27s+person%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=2000. Thus if the victim could have prevented the taking if not for the force, violence, or threat posed by the defendant, this attendant circumstance is present.Jones v. State, 652 So. 2d 346 (1995), accessed March 19, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=11856873917512077763&q= robbery+%22from+the+victim%27s+person%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=2000.

Example of Robbery Attendant Circumstances

Review the example given in Section 11 "Example of Robbery Act" with Rodney and Lindsey. In this example, Rodney tells Lindsey he will kill her if she doesn’t write him a check for fifteen thousand dollars. Change this example so that Rodney knows Lindsey has recently withdrawn fifteen thousand dollars in cash from the bank. Rodney demands the cash, tells Lindsey he will kill her if she doesn’t give it to him, and gestures toward a bulge in his front jacket pocket that appears to be a weapon. Lindsey tells Rodney, “The money is in my purse, but if you take it, you will be ruining my life!” and points to her purse, which is on the kitchen table a few feet away. Rodney walks over to the table, opens Lindsey’s purse, and removes a large envelope stuffed with bills. In this scenario, the attendant circumstances for robbery appear to be present. Rodney took the property of another without consent. Although the money was not on Lindsey’s person, it was in her presence and subject to her control. If Rodney had not threatened Lindsey’s life, she could have prevented the taking. Thus Rodney has most likely committed robbery and is subject to prosecution for and conviction of this offense.

Robbery Intent

The criminal intent element required for robbery is the same as the criminal intent element required for larceny and extortion in many jurisdictions. The defendant must have the specific intent or purposely to commit the criminal act and to deprive the victim of the property permanently.Metheny v. State, 755 A.2d 1088 (2000), accessed March 19, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=10315203348655203542&q= robbery+%22deprive+permanently%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5. Some jurisdictions do not require the intent to permanently deprive the victim of property and include temporary takings in the robbery statute.Fla. Stat. Ann. § 812.13, accessed March 19, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/florida/crimes/812.13.html.

Example of Robbery Intent

Review the example with Rodney and Lindsey in Section 11 "Example of a Case Lacking Extortion Intent". In this example, Rodney demands a loan from Lindsey in the amount of fifteen thousand dollars and threatens to expose her drug trafficking activities if she doesn’t comply. Change this example so that Rodney tells Lindsey to loan him fifteen thousand dollars or he will kill her, gesturing at a bulge in his front jacket pocket that appears to be a weapon. In a jurisdiction that requires the criminal intent to permanently deprive the victim of property for robbery, Rodney does not have the appropriate criminal intent. In a jurisdiction that allows for the intent to temporarily deprive the victim of property for robbery, Rodney has the appropriate criminal intent and may be charged with and convicted of this offense.

Robbery Causation and Harm

The criminal act supported by the criminal intent must be the factual and legal cause of the robbery harm, which is the same as the harm requirement for larceny and extortion: the property must be transferred to the defendant.Oklahoma Uniform Jury Instructions No. CR 4-141, accessed March 19, 2011, http://www.okcca.net/online/oujis/oujisrvr.jsp?o=248. In some jurisdictions, no transfer of property needs to take place, and the crime is complete when the defendant employs the force or threat with the appropriate criminal intent.Williams v. State, 91 S.W. 3d 54 (2002), accessed March 19, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=9518129765374420507&q= robbery+%22transfer+of+property%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=2000.

Example of Robbery Harm

Review the example with Rodney and Lindsey in Section 11 "Example of Robbery Attendant Circumstances". In this example, Rodney threatens to kill Lindsey if she does not give him fifteen thousand dollars out of her purse and gestures to a bulge in his front jacket pocket that appears to be a weapon. Change this example so that Lindsey leaps off of the couch and tackles Rodney after his threat. She reaches into his pocket and determines that Rodney’s “gun” is a plastic water pistol. Rodney manages to get out from under Lindsey and escapes. If Rodney and Lindsey are in a jurisdiction that requires a transfer of property for the harm element of robbery, Rodney has probably only committed attempted robbery because Rodney did not get the chance to take the money out of Lindsey’s purse. If Rodney and Lindsey are in a jurisdiction that does not require a transfer of property for the harm element of robbery, Rodney may be subject to prosecution for and conviction of this offense.

Figure 11.5 Diagram of Defenses to Robbery

Robbery Grading

As stated previously, robbery is generally graded as a serious felony that can serve as the predicate felony for first-degree felony murderCal. Penal Code § 189, accessed March 19, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/california/penal/189.html. and a strike in states that have three strikes statutes.Cal. Penal Code § 1192.7, accessed March 19, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/california/penal/1192.7.html. Robbery grading is aggravated by the use of a weapon or when the defendant inflicts serious bodily injury.Tex. Penal Code § 29.03, accessed March 12, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/texas/penal/29.03.00.html. The Model Penal Code grades robbery as a felony of the second degree, unless the actor attempts to kill anyone or purposely inflicts or attempts to inflict serious bodily injury, in which case it is graded as a felony of the first degree (Model Penal Code § 222.1(2)).

Table 11.2 Comparing Larceny, Extortion, and Robbery

| Crime | Criminal Act | Criminal Intent | Attendant Circumstance | Harm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Larceny | Taking by stealth or false representation of fact | Specific or purposely to deprive the victim of property permanently* | Victim’s property, lack of victim consent | Property transfer |

| Extortion | Taking by threat of future harm; not necessarily physical | Specific or purposely to deprive the victim of property permanently* | Victim’s property; the victim consents based on fear | Property transfer |

| Robbery | Taking by force or threat of imminent force | Specific or purposely to deprive the victim of property permanently* | Victim’s property, lack of victim consent, property is taken from the victim’s person or presence | Property transfer** |

| *In some jurisdictions, the defendant can intend a temporary taking. | ||||

| **In some jurisdictions, the victim does not need to transfer the property to the defendant. | ||||

Receiving Stolen Property

All jurisdictions criminalize receiving stolen propertyReceiving, buying, retaining, selling, or disposing of stolen property., to deter theft and to break up organized criminal enterprises that benefit from stealing and selling stolen goods. Receiving stolen property criminal statutes often are targeted at pawnbrokers or fencesA defendant who facilitates the buying and selling of stolen property. who regularly buy and sell property that is the subject of one of the theft crimes discussed in the preceding sections. As stated, the Model Penal Code includes receiving stolen property in its consolidated theft offense (Model Penal Code §§ 223.1, 223.6). Receiving stolen property has the elements of criminal act, criminal intent, attendant circumstances, causation, and harm, as is explored in Section 11.2.3 "Receiving Stolen Property".

Receiving Stolen Property Act

The criminal act element required for receiving stolen property in many jurisdictions is receiving, retaining, disposing of,Ala. Code § 13A-8-16, accessed March 12, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/alabama/criminal-code/13A-8-16.html. selling,Cal. Penal Code § 496, accessed March 12, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/california/penal/496.html. trafficking in,Fla. Stat. Ann. § 812.019, accessed March 12, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/florida/crimes/812.019.html. buying, or aiding in concealmentMass. Gen. Laws ch. 266 § 60, http://law.onecle.com/massachusetts/266/60.html. of stolen personal property. The Model Penal Code defines the criminal act element as receiving, retaining, or disposing of stolen movable property (Model Penal Code § 223.6(1)). The criminal act does not generally require the defendant to be in actual physical possession of the property, as long as the defendant retains control over the item(s).Ga. Code § 16-8-7, accessed March 12, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/georgia/16/16-8-7.html. This would be a constructive possession. The Model Penal Code defines receiving as “acquiring possession, control or title, or lending on the security of the property” (Model Penal Code § 223.6(1)). Note that the criminal act element of receiving stolen property includes both buying and selling. Thus dealers that regularly purchase and then sell stolen items can be prosecuted for both of these acts under the same statute.

Example of Receiving Stolen Property Act

Chanel, a fence who deals in stolen designer perfume, arranges a sale between one of her thieves, Burt, and a regular customer, Sandra. Chanel directs Burt to drop off a shipment of one crate of the stolen perfume at Chanel’s storage facility and gives Burt the key. Chanel pays Burt five thousand dollars for the perfume delivery. Chanel thereafter accepts a payment of ten thousand dollars from Sandra and gives Sandra another key with instructions to pick up the perfume the next day after it has been delivered. Chanel could probably be charged with and convicted of receiving stolen property in most jurisdictions. Although Chanel did not ever acquire actual possession of the stolen designer perfume, Chanel had control over the property or constructive possession through her storage facility. Chanel’s acts of buying the perfume for five thousand dollars and then selling it for ten thousand dollars both would be criminalized under one statute in many jurisdictions. Thus Chanel could be prosecuted for both acts as separate charges of receiving stolen property.

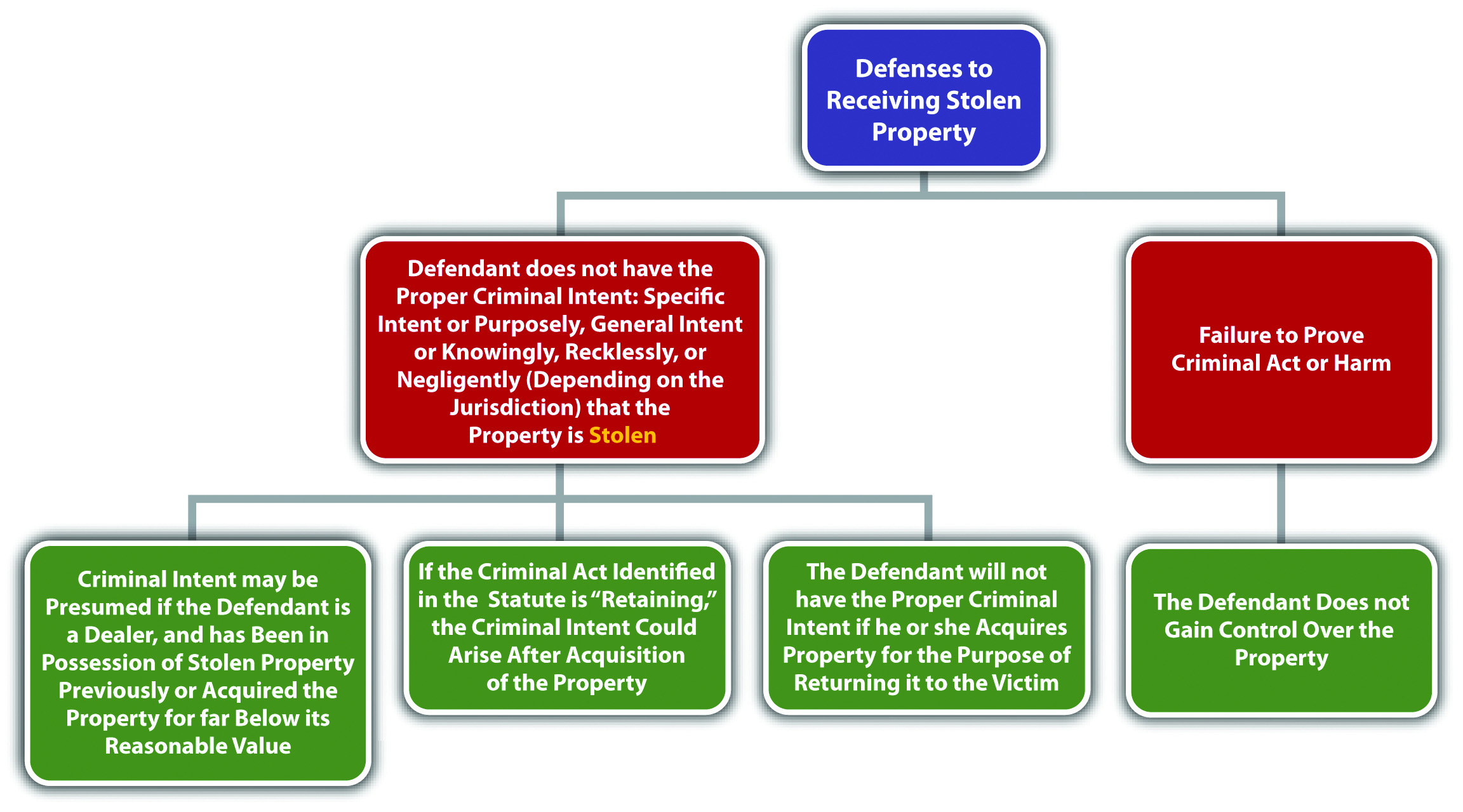

Receiving Stolen Property Intent

The criminal intent element required for receiving stolen property has two parts. First, the defendant must have the intent to commit the criminal act, which could be specific intent or purposely, general intent or knowingly, recklessly, or negligently to either buy-receive or sell-dispose of stolen personal property, depending on the jurisdiction. This means that the defendant must have actual knowledge that the property is stolen,Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 266 § 60, accessed March 13, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/massachusetts/266/60.html. or the defendant must be aware or should be aware of a risk that the property is stolen.Ala. Code § 13A-8-16(a), accessed March 12, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/alabama/criminal-code/13A-8-16.html. The Model Penal Code requires the defendant to purposely commit the act knowing that the property is stolen or believing that the property has probably been stolen (Model Penal Code § 223.6(1)). The Model Penal Code also provides a presumption of knowledge or belief when the defendant is a dealer, which is defined as a “person in the business of buying or selling goods including a pawnbroker,” and has been found in possession or control of property stolen from two or more persons on more than one occasion, or has received stolen property in another transaction within the year preceding the transaction charged, or acquires the property for consideration far below its reasonable value (Model Penal Code § 223.6(2)). Many state statutes have a similar provision.Ala. Code § 13A-8-16, accessed March 13, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/alabama/criminal-code/13A-8-16.html.

The second aspect of criminal intent for receiving stolen property is the defendant’s specific intent or purposeful desire to deprive the victim of the property permanently, which is required in some jurisdictions.Hawaii Criminal Jury Instructions No. 10.00, 10.20, accessed March 13, 2011, http://www.courts.state.hi.us/docs/docs4/crimjuryinstruct.pdf. This creates a failure of proof or affirmative defense that the defendant received and retained the stolen property with the intent to return it to the true owner.Ga. Code § 16-8-7(a), accessed March 12, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/georgia/16/16-8-7.html. The Model Penal Code also provides a defense if “the property is received, retained, or disposed of with purpose to restore it to the owner” (Model Penal Code § 223.6(1)).

Example of Receiving Stolen Property Intent

Chip’s iPod breaks, so he decides to go to the local electronics store and buy a new one. As he is approaching the store, Heather saunters over from a nearby alley and asks him if he wants to buy a brand new iPod for ten dollars. Suspicious of the price, Chip asks Heather to see the iPod. She hands it to him, and he notices that the box looks like it has been tampered with and a price tag removed. He shrugs, takes ten dollars out of his wallet, and hands it to Heather in exchange for the iPod. In jurisdictions that require actual knowledge that the property is stolen, Chip probably does not have the appropriate criminal intent for receiving stolen property because he did not know Heather and had no way of knowing if Heather was selling him stolen property. In jurisdictions that require awareness of a risk that the property is stolen, Chip may have the appropriate criminal intent because he knew the price was too low and noticed that the box had been tampered with to remove evidence of an actual price or vendor.

Change the example so that Chip is a pawnshop broker, and Heather brings the iPod into his shop to pawn for the price of ten dollars. In many jurisdictions, if Chip accepts the iPod to pawn, this creates a presumption of receiving stolen property criminal intent. Chip is considered a dealer, and in many jurisdictions, dealers who acquire property for consideration that they know is far below the reasonable value are subject to this type of presumption.

Change the example again so that Chip notices the following message written on the back of the iPod box: “This iPod is the property of Eugene Schumaker.” Chip is Eugene Schumaker’s friend, so he pays Heather the ten dollars to purchase the iPod so he can return it to Eugene. In many jurisdictions and under the Model Penal Code, Chip can use his intent to return the stolen property to its true owner as a failure of proof or affirmative defense to receiving stolen property.

Retaining Stolen Property

If retaining is the criminal act element described in the receiving stolen property statute, a defendant can still be convicted of receiving stolen property if he or she originally receives the property without the appropriate criminal intent, but later keeps the property after discovering it is stolen.Connecticut Criminal Jury Instructions §§53a-119(8) and 53a-122 through 53a-125b, accessed March 13, 2011, http://www.jud.ct.gov/ji/criminal/part9/9.1-15.htm.

Example of Retaining Stolen Property

Review the example with Chip and Heather in Section 11 "Example of Receiving Stolen Property Intent". Change this example so that Chip is not a dealer and is offered the iPod for one hundred dollars, which is fairly close to its actual value. Chip purchases the iPod from Heather and thereafter drives home. When he gets home, he begins to open the box and notices the message stating that the iPod is the property of Eugene Schumaker. Chip thinks about it for a minute, continues to open the box, and then retains the iPod for the next six months. If Chip is in a state that defines the criminal act element for receiving stolen property as retains, then Chip most likely committed the criminal act with the appropriate criminal intent (knowledge that the property is stolen) and may be subject to prosecution for and conviction of this offense.

Receiving Stolen Property Attendant Circumstances

The property must be stolen for this crime, so the prosecution must prove the attendant circumstances that the property belongs to another and lack of victim consent.

Receiving Stolen Property Causation

The criminal act must be the factual and legal cause of receiving stolen property harm, which is defined in Section 11 "Receiving Stolen Property Harm".

Receiving Stolen Property Harm

The defendant must buy, receive, retain, sell, or dispose of stolen property for the completed crime of receiving stolen property in most jurisdictions.Ala. Code § 13A-8-16, accessed March 13, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/alabama/criminal-code/13A-8-16.html. If the defendant does not actually gain or transfer control of the property, only attempted receiving stolen property can be charged.

Figure 11.6 Diagram of Defenses to Receiving Stolen Property

Receiving Stolen Property Grading

Receiving stolen property is graded as a felony-misdemeanorCal. Penal Code § 496, accessed March 13, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/california/penal/496.html. or as a misdemeanor if the stolen property is of low value and a felony if the stolen property is of high value.Ga. Code § 16-8-12, accessed March 13, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/georgia/16/16-8-12.html.

Figure 11.7 Diagram of Crimes Involving Theft

Key Takeaways

- The criminal act element required for extortion is typically a theft of property accomplished by a threat to cause future harm to the victim.

- The criminal intent element required for extortion is typically the specific intent or purposely to unlawfully deprive the victim of property permanently. However, in some jurisdictions, it is the general intent or knowingly to perform the criminal act.

- In many jurisdictions, it is an affirmative defense to extortion that the property taken by threat to expose a secret or accuse anyone of a criminal offense is taken honestly, as compensation for property, or as restitution or indemnification for harm done by the secret or crime.

- The attendant circumstances of extortion are that the property belongs to another and that the victim consents to transferring the property to the defendant based on fear inspired by the defendant’s threat.

- The harm element required for extortion is that the defendant obtains the property of another.

- Extortion is graded as a felony in most jurisdictions.

- Robbery requires a taking accomplished by force or threat of imminent force. Extortion requires a taking by threat of future harm that is not necessarily force, and larceny generally requires a taking by stealth or a false representation of fact. Robbery also requires the attendant circumstance that the property be taken from the victim’s person or presence and is generally graded more severely than larceny or extortion.

- Robbery is typically graded as a serious felony, which is a strike in jurisdictions that have three strikes statutes, and a predicate felony for first-degree felony murder.

- The criminal act element required for receiving stolen property is typically buying-receiving, retaining, and selling-disposing of stolen personal property.

- The defendant must have the intent to commit the criminal act of receiving stolen property, which could be specific intent or purposely, general intent or knowingly, recklessly, or negligently to either buy-receive or sell-dispose of stolen personal property, depending on the jurisdiction. If “retain” is the criminal act element specified in the receiving stolen property statute, a defendant who obtains property without knowledge that it is stolen commits the offense if he or she thereafter keeps property after discovering that it is stolen. The defendant must also have the specific intent or purposeful desire to deprive the victim of the property permanently in some jurisdictions.

- A failure of proof or affirmative defense to receiving stolen property in some jurisdictions is that the defendant received and retained the stolen property with the intent to return it to the true owner.

- The attendant circumstances for receiving stolen property are that the property belongs to another and lack of victim consent. The harm element of receiving stolen property is that the defendant buy-receive, retain, or sell-dispose of stolen personal property.

- Receiving stolen property is graded as a felony-misdemeanor or a misdemeanor if the stolen property is of low value and a felony if the stolen property is of high value.

Exercises

Answer the following questions. Check your answers using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

- Review the example given in Section 11 "Example of a Case Lacking the Attendant Circumstance of Victim Reliance Required for False Pretenses" with Jeremy and Chuck. In this example, Chuck shows Jeremy a video he made of Jeremy reading a magazine instead of tuning up Chuck’s taxi. Chuck thereafter threatens to show this video to the district attorney if Jeremy does not pay him two hundred dollars. Has Chuck committed a crime in this scenario? If your answer is yes, which crime?

- Read State v. Robertson, 531 S. E. 2d 490 (2000). In Robertson, the Court of Appeals of North Carolina reversed the defendant’s conviction for robbery of the victim’s purse. What was the basis of the court’s reversal of conviction? The case is available at this link: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=10266690205116389671&q= robbery+%22purse+snatching%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=2000.

- Read People v. Pratt, 656 N.W.2d 866 (2002). In Pratt, the defendant was convicted of receiving stolen property for taking and concealing his girlfriend’s vehicle. The defendant appealed, claiming that there was no evidence to indicate that he intended to permanently deprive his girlfriend of the vehicle, and thus it was not “stolen.” Did the Court of Appeals of Michigan uphold the defendant’s conviction? Why or why not? The case is available at this link: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=9260508991670862336&q= actual+knowledge+%22receiving+stolen+property%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=2000.

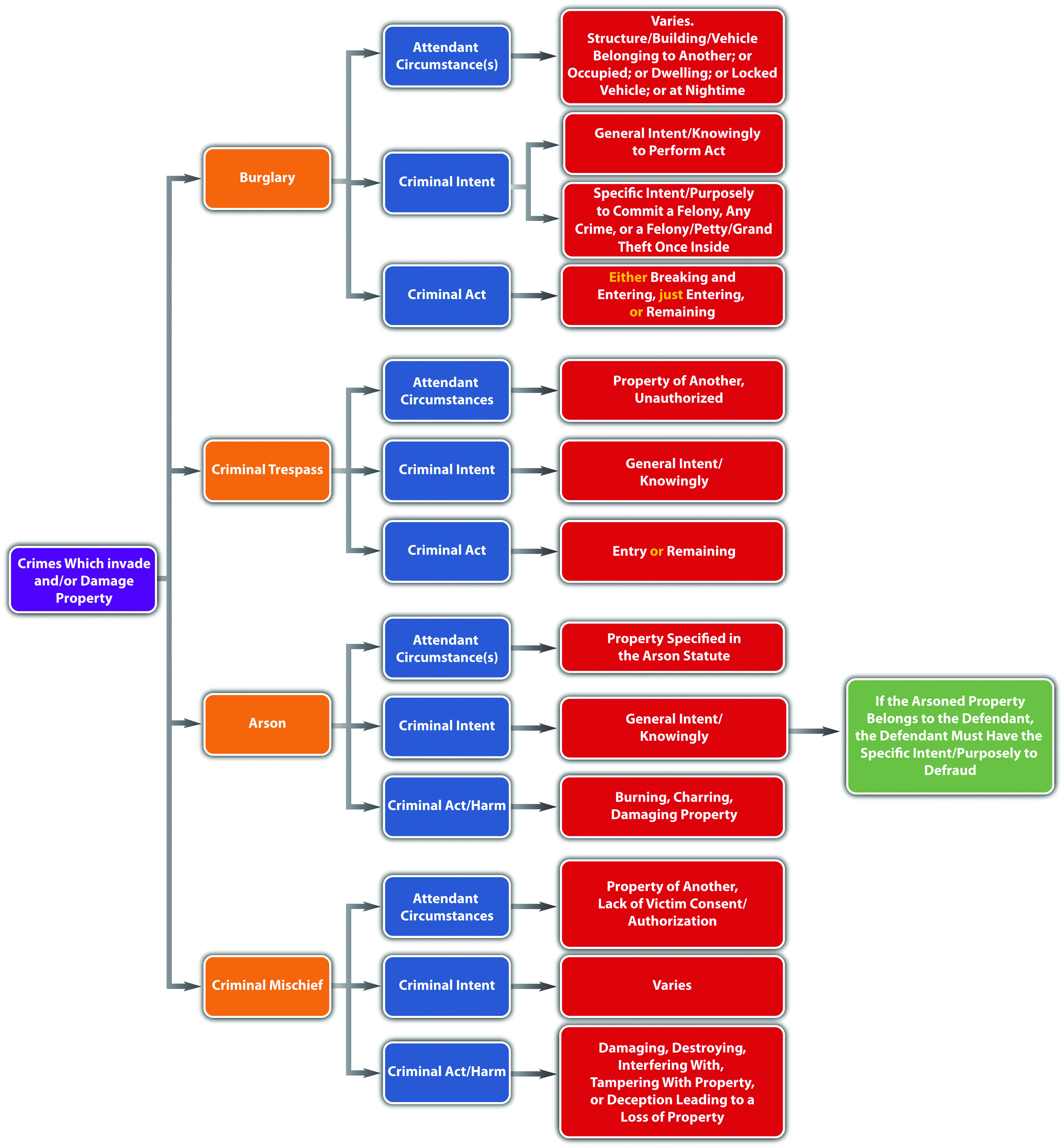

11.3 Crimes That Invade or Damage Property

Learning Objectives

- Define the criminal act element required for burglary.

- Define the criminal intent element required for burglary.

- Define the attendant circumstances required for burglary.

- Analyze burglary grading.

- Define the elements of criminal trespass, and analyze criminal trespass grading.

- Define the criminal act element required for arson.

- Define the criminal intent element required for arson.

- Define the attendant circumstances required for arson.

- Define the harm element required for arson.

- Analyze arson grading.

- Define the elements of criminal mischief, and analyze criminal mischief grading.

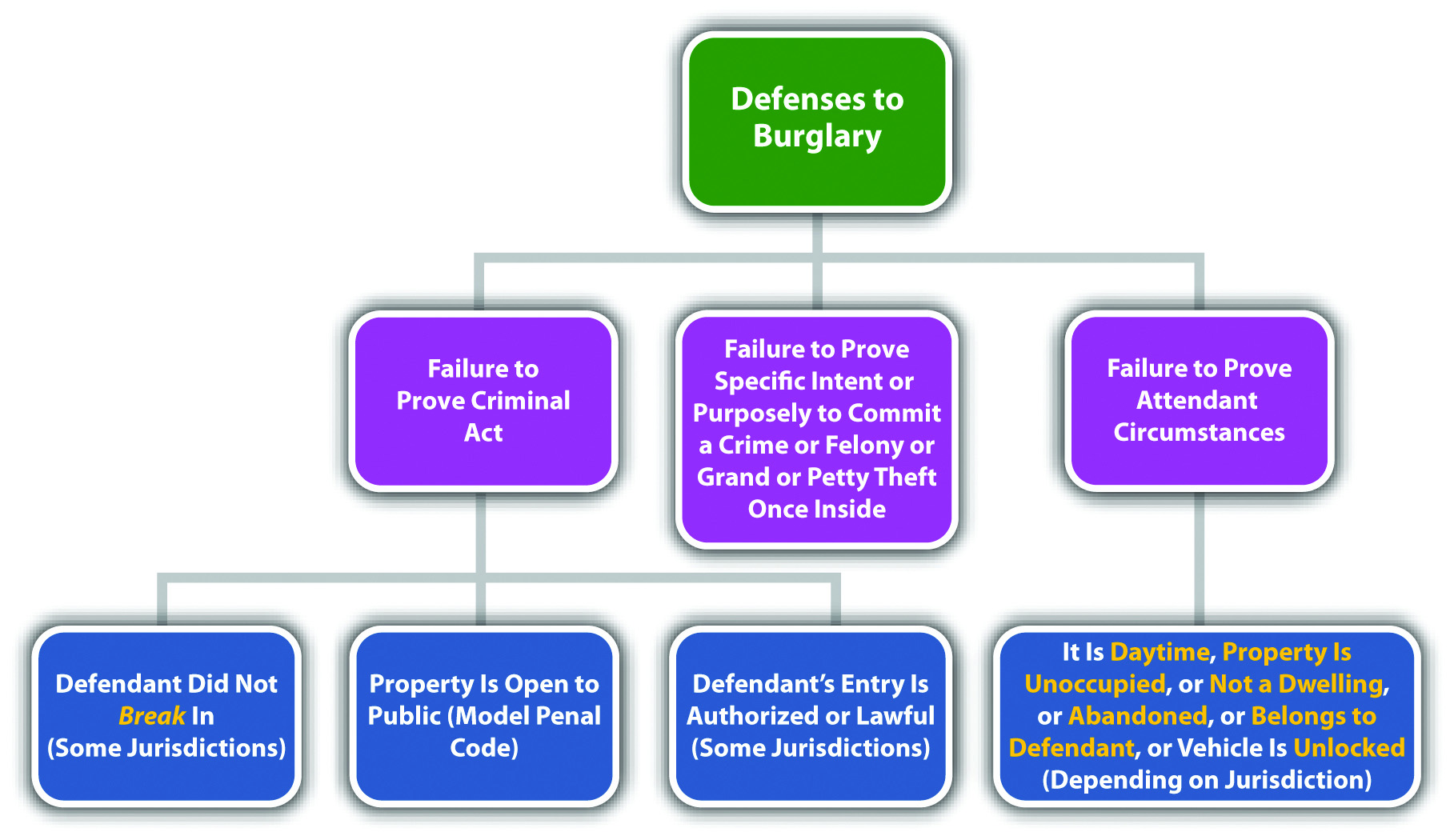

Burglary

Although burglaryBreaking, entering, or remaining in a structure, building, or vehicle with the intent to commit a crime or felony once inside. is often associated with theft, it is actually an enhanced form of trespassing. At early common law, burglary was the invasion of a man’s castle at nighttime, with a sinister purpose. Modern jurisdictions have done away with the common-law attendant circumstances and criminalize the unlawful entry into almost any structure or vehicle, at any time of day. Burglary has the elements of criminal act, criminal intent, and attendant circumstances, as is explored in Section 11.3.1 "Burglary".

Burglary Act

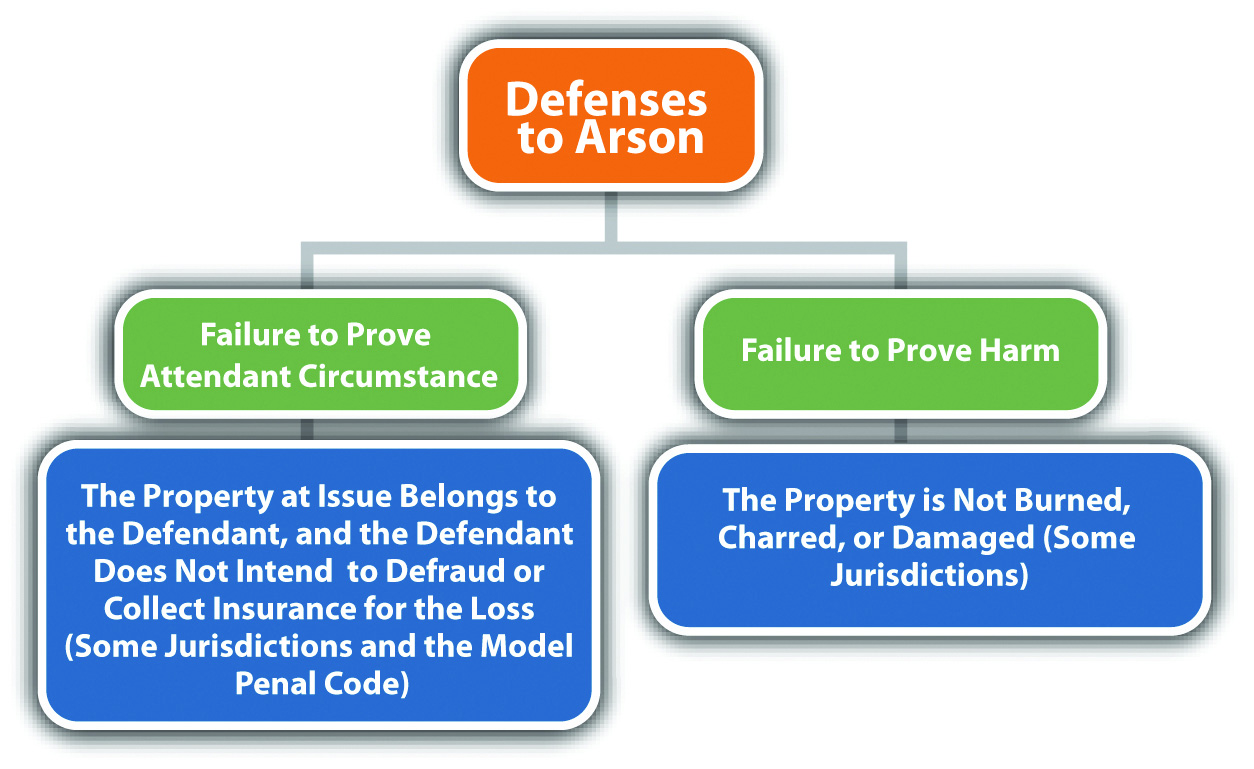

The criminal act element required for burglary varies, depending on the jurisdiction. Many jurisdictions require breaking and entering into the area described in the burglary statute.Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 266 § 14, accessed March 20, 2011, http://law.justia.com/codes/massachusetts/2009/PARTIV/TITLEI/CHAPTER266/Section14.html. Some jurisdictions and the Model Penal Code only require entering (Model Penal Code § 221.1). Other jurisdictions include remaining in the criminal act element.Fla. Stat. Ann. § 810.02(b) (2), http://law.justia.com/codes/florida/2010/TitleXLVI/chapter810/810_02.html.