This is “Sex Offenses and Crimes Involving Force, Fear, and Physical Restraint”, chapter 10 from the book Introduction to Criminal Law (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 10 Sex Offenses and Crimes Involving Force, Fear, and Physical Restraint

Source: Image courtesy of Tara Storm.

Among the evils that both the common law and later statutory prohibitions against kidnapping sought to address were the isolation of a victim from the protections of society and the law and the special fear and danger inherent in such isolation.

State v. Salaman, cited in Section 10.4 "Kidnapping and False Imprisonment"

10.1 Sex Offenses

Learning Objectives

- Compare common-law rape and sodomy offenses with modern rape and sodomy offenses.

- Define the criminal act element required for rape.

- Define the attendant circumstance element required for rape.

- Ascertain the amount of resistance a victim must demonstrate to evidence lack of consent.

- Ascertain whether the victim’s testimony must be corroborated to convict a defendant for rape.

- Define the criminal intent element required for rape.

- Analyze the relationship between the criminal intent element required for rape and the mistake of fact defense allowed for rape in some jurisdictions.

- Define the harm element required for rape.

- Identify the primary components of rape shield laws.

- Identify the most prevalent issues in acquaintance rape.

- Compare spousal rape with rape.

- Identify the elements of statutory rape, and compare statutory rape with rape.

- Compare sodomy, oral copulation, and incest with rape.

- Analyze sex offenses grading.

- Identify the primary components of sex offender registration statutes.

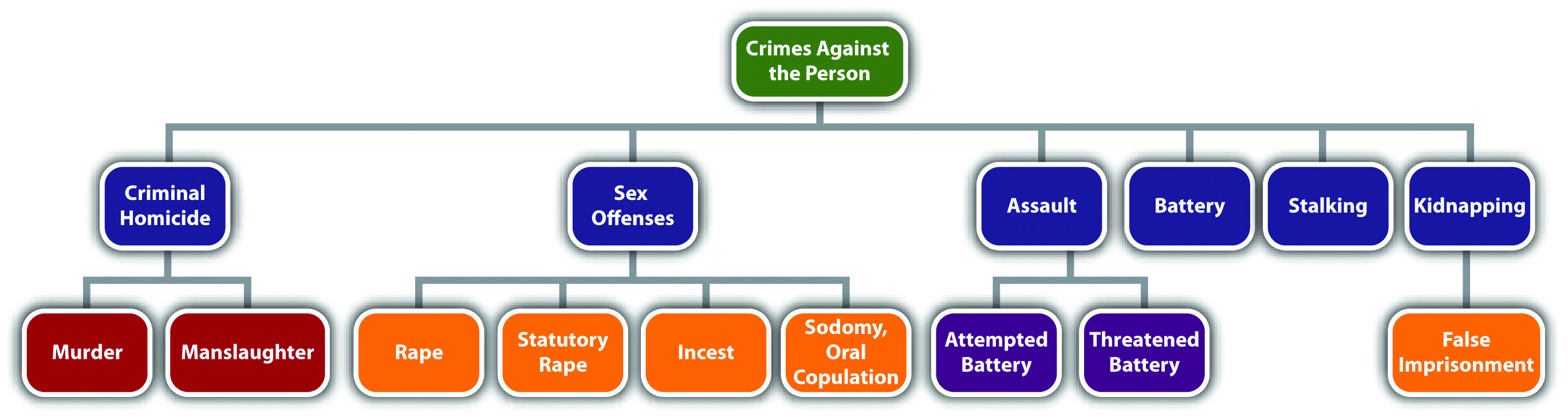

In this section, you learn the elements of rapeThe forcible sexual penetration of a victim without consent. and related sex offenses and examine defenses based on consent. In upcoming sections, you analyze the elements of other crimes involving force, fear, and physical restraint, including assault, battery, domestic violence, stalking, and kidnapping.

Synopsis of the History of Rape and Sodomy

The word rape has its roots in the Latin word rapere, which means to steal or seize. At early common law, rape was a capital offense. The elements of rape were forcible sexual intercourse, by a man, with a woman not the spouse of the perpetrator, conducted without consent, or with consent obtained by force or threat of force.Donna Macnamara, “History of Sexual Violence,” Interactive theatre.org website, accessed February 8, 2011, http://www.interactivetheatre.org/resc/history.html. The rape prosecution required evidence of the defendant’s use of force, extreme resistance by the victim, and evidence that corroborated the rape victim’s testimony. The common law also recognized the crime of sodomy. In general, sodomy was the penetration of the male anus by a man. Sodomy was condemned and criminalized even with consent because of religious beliefs deeming it a crime against nature.“Sex Offenses,” Lawbrain.com website, accessed February 8, 2011, http://lawbrain.com/wiki/Sex_Offenses.

In the 1970s, many changes were made to rape statutes, updating the antiquated common-law approach and increasing the chances of conviction. The most prominent changes were eliminating the marital rape exemption and the requirement of evidence to corroborate the rape victim’s testimony, creating rape shield laws to protect the victim, and relaxing the necessity for the defendant’s use of force or resistance by the victim.Matthew R. Lyon, “No means No? Withdrawal of Consent During Intercourse and the Continuing Evolution of the Definition of Rape,” Findarticles.com website, accessed February 8, 2011, http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb6700/is_1_95/ai_n29148498/pg_3/?tag=content;col1. Many jurisdictions also changed the name of rape to sexual battery, sexual assault, or unlawful sexual conduct and combined sexual offenses like rape, sodomy, and oral copulation into one statute. Although some states still have statutes that provide the death penalty for rape, the US Supreme Court has held that rape, even child rape, cannot be considered a capital offense without violating the Eighth Amendment cruel and unusual punishment clause, rendering these statutes unenforceable.Kennedy v. Louisiana, 128 S. Ct. 2641 (2008), accessed February 8, 2011, http://www.oyez.org/cases/2000-2009/2007/2007_07_343.

Sodomy law has likewise been updated to make sodomy a gender-neutral offense and preclude the criminalization of consensual sexual conduct between adults. The US Supreme Court has definitively held that consensual sex between adults may be protected by a right of privacy and cannot be criminalized without a sufficient government interest.Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003), accessed February 8, 2011, http://www.oyez.org/cases/2000-2009/2002/2002_02_102.

Table 10.1 Comparing Common Law Rape and Sodomy with Modern Statutes

| Crime | Criminal Act | Lack of Victim Consent? | Victim Resistance? | Other Differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common-law rape | Penis-vagina penetration | Yes | Yes, extreme resistance | Corroborative evidence required; no spousal rape; capital crime |

| Modern rape | Some states include any sexual penetration | Yes | Not if force is used, or threat of force that would deter a reasonable person from resisting (See section 10.1.2.2.2.) | No corroborative evidence required; spousal rape is a crime in some jurisdictions; rape is not a capital crime. |

| Common-law sodomy | Male penis-male anus penetration | No. Even consensual sodomy was criminal. | No. Even consensual sodomy was criminal. | |

| Modern sodomy | Gender-neutral penis-anus penetration | Yes | Same as modern rape, above | Consensual sodomy in prison or jail is still criminal in some jurisdictions. (See section 10.1.7.) |

Rape Elements

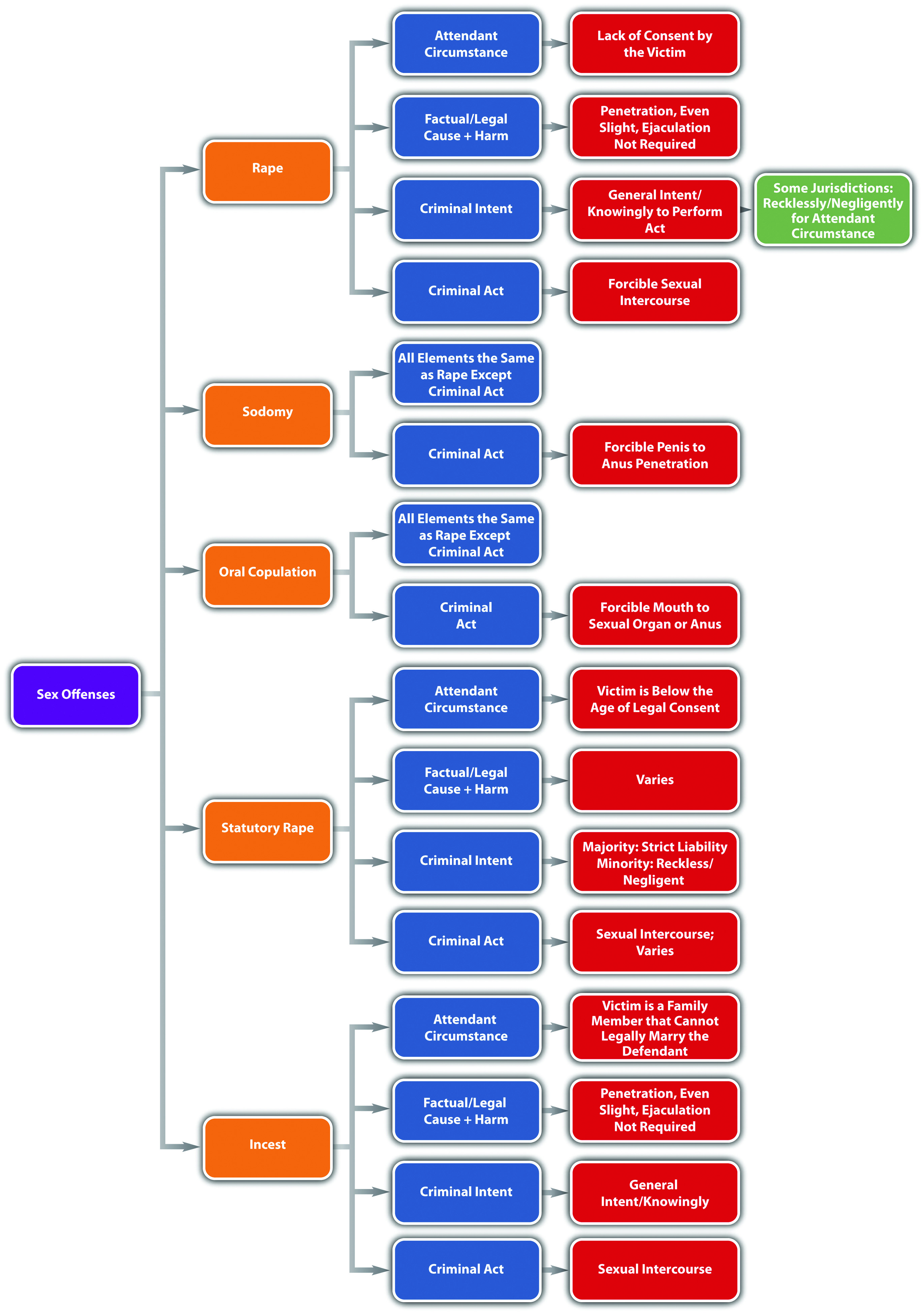

In modern times, rape is a crime that has the elements of criminal act, criminal intent, causation, and harm. Rape also has an attendant circumstance element, which is lack of consent by the victim.

Rape Act

The criminal act element required for rape in many states is sexual intercourse, accomplished by force or threat of force.Md. Code Ann. § 3-303, accessed February 8, 2011, http://law.justia.com/maryland/codes/2005/gcr/3-303.html. Sexual intercourse is typically defined as penetration of a woman’s vagina by a man’s penis and can also be referred to as vaginal intercourse.Md. Code Ann. § 3-301(g), accessed February 8, 2011, http://law.justia.com/maryland/codes/2005/gcr/3-301.html. Some jurisdictions include the penetration of the woman’s vagina by other body parts, like a finger, as sexual intercourse.K.S.A. § 21-3501(1), accessed February 8, 2011, http://law.justia.com/kansas/codes/2006/chapter21/statute_11553.html. The Model Penal Code defines the criminal act element required for rape as sexual intercourse that includes “intercourse per os or per anum,” meaning oral and anal intercourse (Model Penal Code § 213.0(2)). In most jurisdictions, a man or a woman can commit rape.K.S.A. § 21-3502, accessed February 8, 2011, http://law.justia.com/kansas/codes/2006/chapter21/statute_11554.html.

Although it is common to include force or threat of force as an indispensible part of the rape criminal act, some modern statutes expand the crime of rape to include situations where the defendant does not use force or threat, but the victim is extremely vulnerable, such as an intoxicated victim, an unconscious victim, or a victim who is of tender years.K.S.A. § 21-3502, accessed February 8, 2011, http://law.justia.com/kansas/codes/2006/chapter21/statute_11554.html. The Model Penal Code includes force, threat of force, and situations where the defendant has impaired the victim’s power to control conduct by administering intoxicants or drugs without the victim’s knowledge or sexual intercourse with an unconscious female or a female who is fewer than ten years old (Model Penal Code § 213.1(1)). Other statutes may criminalize unforced nonconsensual sexual intercourse or other forms of unforced nonconsensual sexual contact as less serious forms of rape with reduced sentencing options.N.Y. Penal Law § 130.25(3), accessed February 10, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/new-york/penal/PEN0130.25_130.25.html.

Example of Rape Act

Alex and Brad play video games while Brad’s sister Brandy watches. Brad tells Alex he is going to go the store and purchase some beer. While Brad is gone, Alex turns to Brandy, pulls a knife out of his pocket, and tells her to take off her pants and lie down. Brandy tells Alex, “No, I don’t want to,” but thereafter acquiesces, and Alex puts his penis into Brandy’s vagina. Alex has probably committed the criminal act element required for rape in most jurisdictions. Although Alex did not use physical force to accomplish sexual intercourse, his threat of force by display of the knife is sufficient. If the situation is reversed, and Brandy pulls out the knife and orders Alex to put his penis in her vagina, many jurisdictions would also criminalize Brandy’s criminal act as rape. If Alex does not use force or a threat of force, but Brandy is only nine years old, some jurisdictions still criminalize Alex’s act as rape, as would the Model Penal Code.

Rape Attendant Circumstance

In many jurisdictions, the attendant circumstance element required for rape is the victim’s lack of consent to the defendant’s act.Md. Code Ann. § 3-304, accessed February 8, 2011, http://law.justia.com/maryland/codes/gcr/3-304.html. Thus victim’s consent could operate as a failure of proof or affirmative defense.

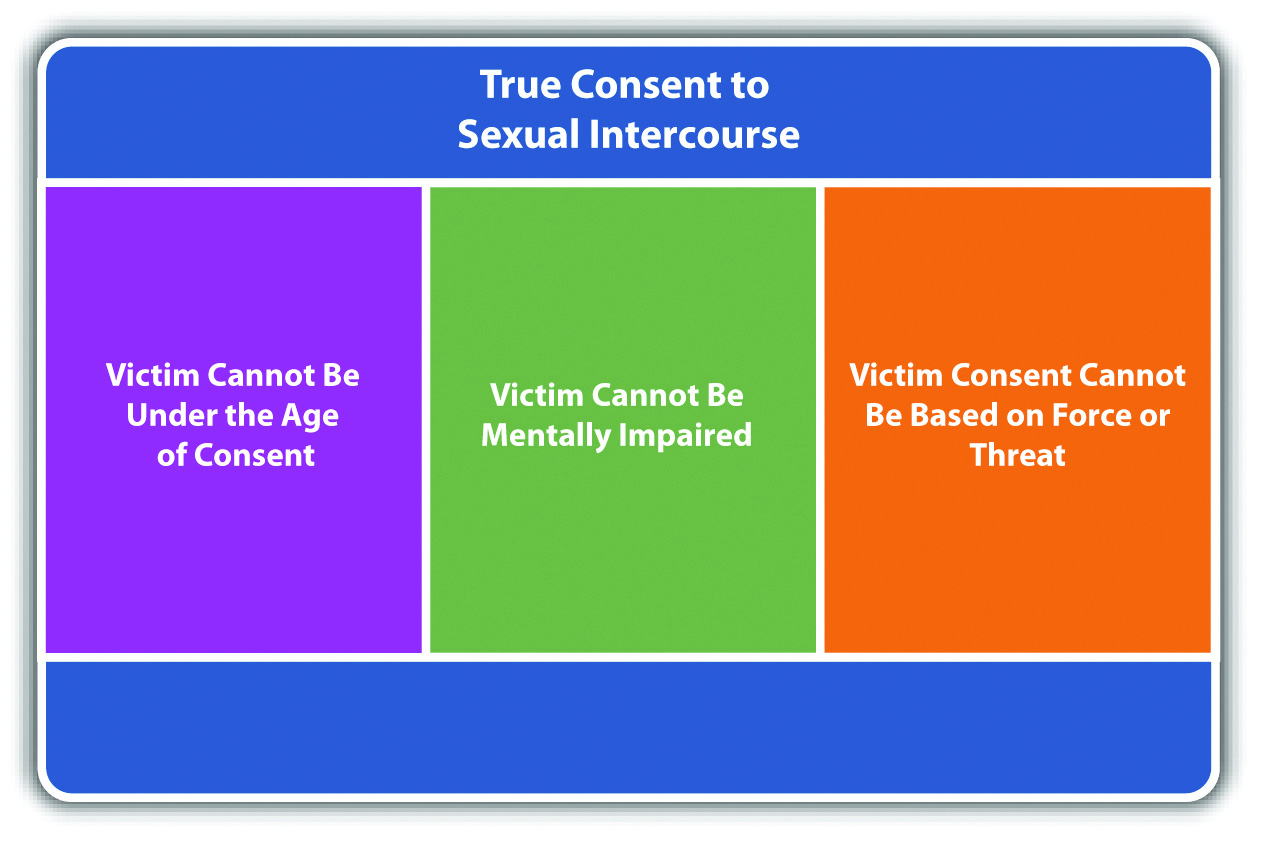

Proving Lack of Consent as an Attendant Circumstance

Proving lack of consent has two components. First, the victim must be legally capable of giving consent. If the victim is under the age of consent or is mentally or intellectually impaired because of a permanent condition, intoxication, or drugs, the prosecution does not have to prove lack of consent in many jurisdictions.K.S.A. § 21-3502, accessed February 8, 2011, http://law.justia.com/kansas/codes/2006/chapter21/statute_11554.html. Sexual intercourse with a victim under the age of consent is a separate crime, statutory rape, which is discussed shortly.

The second component to proving lack of consent is separating true consent from consent rendered involuntarily. Involuntary consent is present in two situations. First, if the victim consents to the defendant’s act because of fraud or trickery—for example, when the victim is unaware of the nature of the act of sexual intercourse—the consent is involuntary. A victim is generally unaware of the nature of the act of sexual intercourse when a doctor shams a medical procedure.Iowa v. Vander Esch, 662 N.W. 2d 689 (2002), accessed February 10, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=4906781834239023314&q= rape+%22fraud+in+the+inducement%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5&as_ylo=2002. This is called fraud in the factumThe defendant fraudulently conceals the nature of the sexual act, like a doctor shamming a medical procedure. Fraud in the factum could render the victim’s consent involuntary.. Fraud in the inducementThe defendant fraudulently conceals the circumstances of the sexual act, like fraudulently representing that the sexual act will cure a disease. Fraud in the inducement does not render the victim’s consent involuntary., which is a fraudulent representation as to the circumstances accompanying the sexual conduct, does not render the consent involuntary in many jurisdictions. An example of fraud in the inducement is a defendant’s false statement that the sexual intercourse will cure a medical condition.Boro v. Superior Court, 163 Cal. App. 3d 1224 (1985), accessed February 17, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=8450241145233624189&q= Boro+v.+Superior+Court&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5.

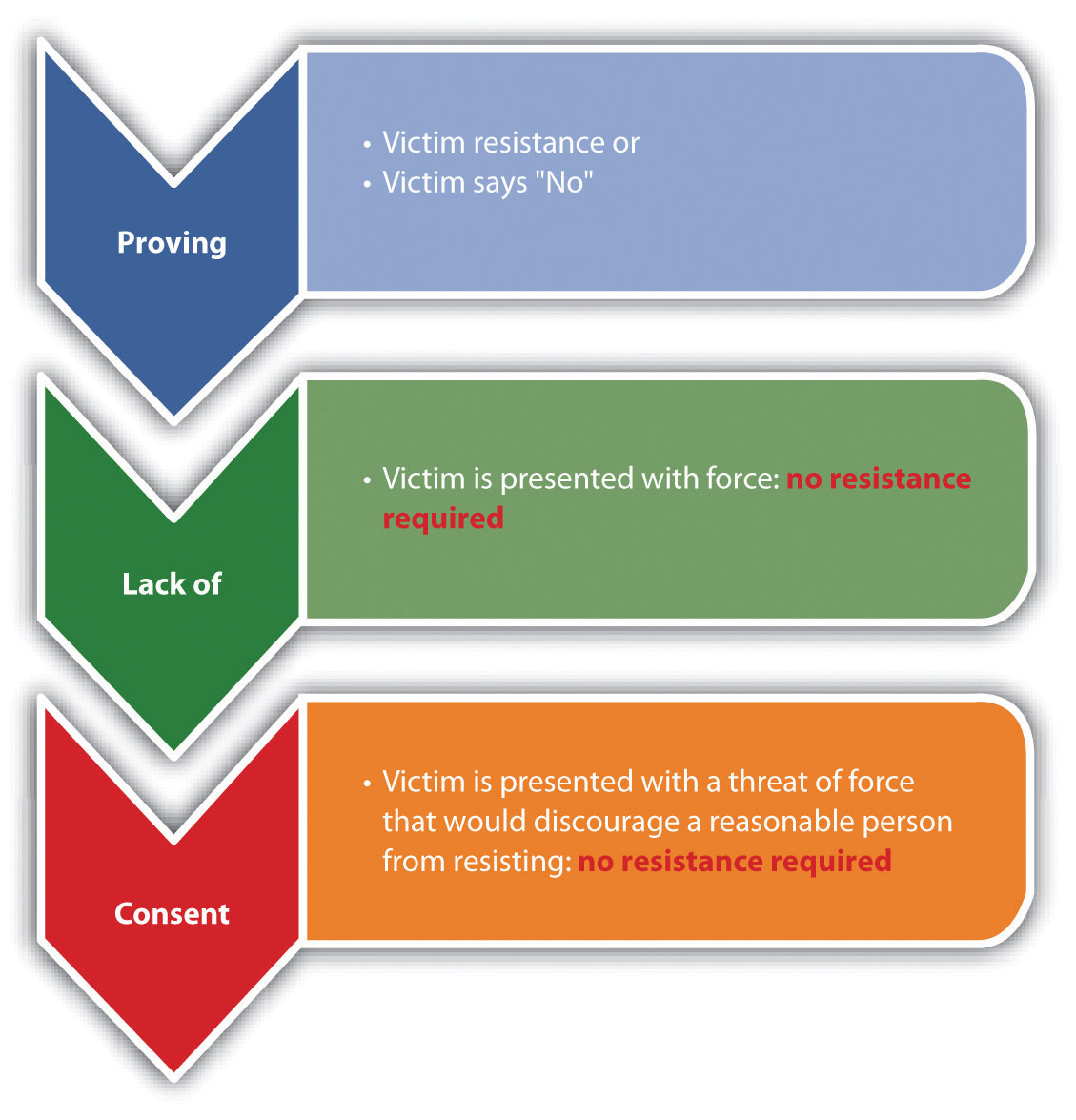

A more common example of involuntary consent is when the victim consents to the defendant’s act because of force or threat of force. The prosecution generally proves this type of consent is involuntary by introducing evidence of the victim’s resistance.

Figure 10.1 Diagram of Consent

Proving Involuntary Consent by the Victim’s Resistance

Under the common law, the victim had to manifest extreme resistance to indicate lack of consent. In modern times, the victim does not have to fight back or otherwise endanger his or her life if it would be futile to do so. In most jurisdictions, the victim only needs to resist to the same extent as a reasonable person under similar circumstances, which is an objective standard.Del. Code Ann. tit. II, § 761(j) (1), accessed February 9, 2011, http://delcode.delaware.gov/title11/c005/sc02/index.shtml#761.

The use of force by the defendant could eliminate any requirement of victim resistance to prove lack of consent.N.Y. Penal Law § 130.05, accessed February 9, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/new-york/penal/PEN0130.05_130.05.html. If the defendant obtains consent using a threat of force, rather than force, the victim may not have to resist if the victim experiences subjective fear of serious bodily injury, and a reasonable person under similar circumstances would not resist, which is an objective standard.Minn. Stat. Ann. § 609.343(c), accessed February 10, 2011, https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/?id=609.343. Threat of force can be accomplished by words, weapons, or gestures. It can also be present when there is a discrepancy in size or age between the defendant and the victim or if the sexual encounter takes place in an isolated location. The Model Penal Code considers it a felony of the third degree and gross sexual imposition when a male has sexual intercourse with a female not his wife by compelling “her to submit by any threat that would prevent resistance by a woman of ordinary resolution” (Model Penal Code § 213.1(2)(a)). Note that the Model Penal Code’s position does not require the threat to be a threat of force; it can be any type of threat that prevents physical resistance.

If the victim does not physically resist the criminal act, the prosecution must prove that the victim affirmatively indicated lack of consent in some other manner. This could be a verbal response, such as saying, “No,” but the verbal response must be unequivocal. In the most extreme case, at least one court has held that a verbal “No” during the act of sexual intercourse is sufficient, and the defendant who continues with sexual intercourse after being told “No” is committing the criminal act of rape.In re John Z., 29 Cal. 4th 756 (2003), accessed February 10, 2011, http://scocal.stanford.edu/opinion/re-john-z-32309.

Figure 10.2 Proving Lack of Consent

The Requirement of Corroborative Evidence

At early common law, a victim’s testimony was insufficient evidence to meet the burden of proving the elements of rape, including lack of consent. The victim’s testimony had to be supported by additional corroborative evidenceEvidence that tends to support a victim’s testimony.. Modern jurisdictions have done away with the corroborative evidence requirement and allow the trier of fact to determine the elements of rape or lack of consent based on the victim’s testimony alone.State v. Borthwick, 880 P.2d 1261 (1994), accessed February 10, 2011, http://www1.law.umkc.edu/suni/CrimLaw/calendar/Class_24_borthwick_case.htm. However, statistics indicate that rape prosecutions often result in acquittal. Thus although technically the victim’s testimony need not be corroborated, it is paramount that the victim promptly report the rape to the appropriate authorities and submit to testing and interrogation to preserve any and all forms of relevant rape evidence.

Example of Rape Attendant Circumstance

Review the example with Brandy and Alex in Section 10 "Example of Rape Act". In this example, after an initial protest, Brandy lies down, takes off her pants, and allows Alex to put his penis in her vagina when he pulls out a knife. It is likely that the trier of fact will find the rape attendant circumstance in this case. Although Brandy acquiesced to Alex’s demands without resisting, she did so after Alex took a knife out of his pocket, which is a threat of force. In addition, Brandy expressed her lack of consent verbally before submitting to Alex’s demand. A trier of fact could determine that Brandy experienced a fear of serious bodily injury from Alex’s display of the knife, and that a reasonable person under similar circumstances would give in to Alex’s demands without physical resistance.

Change this example and assume that after Brad leaves, Alex asks Brandy to have sexual intercourse with him. Brandy responds, “No,” but allows Alex to remove her pants and put his penis in her vagina without physically resisting. The trier of fact must make the determination of whether Alex accomplished the sexual act by force or threat of force and without Brandy’s consent. If Brandy testifies that she said “No” and did not consent to Alex’s act, and Alex testifies that Brandy’s verbal response was insufficient to indicate lack of consent, the trier of fact must resolve this issue of fact, and it can do so based on Brandy’s testimony, uncorroborated, in many jurisdictions. The trier of fact can use the criteria of the difference in age and size between Brandy and Alex, any gestures or words indicating force or threat, and the location and isolation of the incident, among other factors.

Rape Intent

The criminal intent element required for rape in most jurisdictions is the general intent or knowingly to perform the rape criminal act.State v. Lile, 699 P.2d 456 (1985), accessed February 8, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=5958820374035014869&hl=en&as_sdt=2&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr. This may include the intent to use force to accomplish the objective if the state’s rape statute includes force or threat of force as a component of the criminal act.

As Chapter 4 "The Elements of a Crime" stated, occasionally, a different criminal intent supports the other elements of an offense. In some states, negligent intent supports the rape attendant circumstance of lack of victim consent. This creates a viable mistake of fact defense if the defendant has an incorrect perception as to the victim’s consent. To be successful with this defense, the facts must indicate that the defendant honestly and reasonably believed that the victim consented to the rape criminal act.People v. Mayberry, 542 P.2d 1337 (1975), accessed February 11, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=6471351898025391619&hl=en&as_sdt=2&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr. Many jurisdictions expressly disallow the defense, requiring strict liability intent for the lack of consent attendant circumstance.State v. Plunkett, 934 P.2d 113 (1997), accessed February 11, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=17940293485668190575&hl=en&as_sdt=2&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr.

Example of Rape Intent

Review the example with Alex and Brandy in Section 10 "Example of Rape Act". Change the example so that Alex does not display a knife and simply asks Brandy if she would like to have sex with him. Brandy does not respond. Alex walks over to Brandy and removes her pants. Brandy does not protest or physically resist. Thereafter, Alex asks Brandy if she “likes it rough.” Brandy remains silent. Alex physically and forcibly puts his penis in Brandy’s vagina. In states that allow a negligent intent to support the attendant circumstance of rape, Alex may be able to successfully assert mistake of fact as a defense. It appears that Alex has with general intent or knowingly committed forcible sexual intercourse, based on his actions. In most jurisdictions, the jury could be instructed on an inference of this intent from Alex’s behavior under the circumstances. However, if negligent intent is required to support the attendant circumstance of the victim’s lack of consent, the trier of fact may find that Alex’s mistake as to Brandy’s consent was honest and reasonable, based on her lack of response or physical resistance. If Alex is in a jurisdiction that requires strict liability intent to support the attendant circumstance element, Alex cannot raise the defense because Alex’s belief as to Brandy’s consent would be irrelevant.

Rape Causation

The defendant’s criminal act must be the factual and legal cause of the harm, which is defined in Section 10 "Rape Harm".

Rape Harm

The harm element of rape in most jurisdictions is penetration, no matter how slight.Idaho Code Ann. § 18-6101, accessed February 10, 2011, http://www.legislature.idaho.gov/idstat/Title18/T18CH61SECT18-6101.htm. This precludes virginity as a defense. In addition, modern statutes do not require male ejaculation, which precludes lack of semen as a defense.Ala. Code § 13A-6-60, accessed February 11, 2011, http://law.justia.com/alabama/codes/2009/Title13A/Chapter6/13A-6-60.html.

Example of Rape Harm

Review the example with Alex and Brandy in Section 10 "Example of Rape Act". Assume that Brad walks into the room while Alex and Brandy are engaging in sexual intercourse. Brad tackles Alex and pulls him off Brandy. Alex may be charged with rape, not attempted rape, in most jurisdictions. The fact that Alex did not ejaculate does not affect the rape analysis in any way because most jurisdictions do not require ejaculation as a component of the harm element of rape.

Rape Shield Laws

Rape prosecutions can be extremely stressful for the victim, especially when the defendant pursues a consent defense. Before the comprehensive rape reforms of the 1970s, rape defendants would proffer any evidence they could find to indicate that the victim was sexually promiscuous and prone to consenting to sexual intercourse. Fearing humiliation, many rape victims kept their rape a secret, not reporting it to law enforcement. This allowed serial rapists to escape punishment and did not serve our criminal justice goal of deterrence.

In modern times, most states protect rape victims with rape shield lawsStatutes that preclude the admission of evidence in a rape trial of a victim’s previous sexual history unless a judge permits it after a pretrial in camera hearing.. Rape shield laws prohibit the admission of evidence of the victim’s past sexual conduct to prove consent in a rape trial, unless the judge allows it in a pretrial in cameraOutside the presence of the jury. hearing, outside the presence of the jury. Rape shield laws could include the additional protections of the exclusion of evidence relating to the victim’s style of dress to prove consent, the exclusion of evidence that the victim requested the defendant to wear a condom to prove consent, and the affirmation that a victim’s testimony in a rape trial need not be corroborated by other evidence.Fla. Stat. Ann. § 794.022, accessed February 11, 2011, http://law.justia.com/florida/codes/2010/TitleXLVI/chapter794/794_022.html. Most courts permit the admission of evidence proving the victim’s previous consensual sex with the defendant because this evidence is particularly relevant to any consent defense.Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 18-3-407(1) (a), accessed February 14, 2011, http://www.michie.com/colorado/lpext.dll?f=templates&fn=main-h.htm&cp=.

Example of the Effect of a Rape Shield Law

Review the example with Alex and Brandy in Section 10 "Example of Rape Intent". Assume that the jurisdiction in which the example takes place has a rape shield law. If Alex is put on trial for the rape of Brandy and he decides to pursue a consent defense, Alex would not be able to introduce evidence of Brandy’s sexual history with other men unless he receives approval from a judge in an in camera hearing before the trial.

Law and Ethics

Should the Media Be Permitted to Publish Negative Information about a Rape Victim?

In 2003, Kobe Bryant, a professional basketball player, was indicted for sexually assaulting a nineteen-year-old hotel desk clerk. A mistake by a court reporter listed the accuser’s name on a court website.“Rape Case against Bryant Dismissed,” MSNBC.com website, accessed February 27, 2011, http://nbcsports.msnbc.com/id/5861379. The court removed the victim’s name after discovery of the mistake, but the damage was done. Thereafter, in spite of a court order prohibiting the publication of the accuser’s name, the media, including radio, newspaper, Internet, and television, published the accuser’s name, phone number, address, and e-mail address.Tom Kenworty, Patrick O’Driscoll, “Judge Dismisses Bryant Rape Case,” USAtoday.com website, accessed February 27, 2011, http://www.usatoday.com/sports/basketball/nba/2004-09-01-kobe-bryant-case_x.htm. Products like underwear, t-shirts, and coffee mugs with pictures of the accuser and Bryant in sexual positions were widely available for sale, and the accuser received constant harassment, including death threats.Richard Haddad, “Shield or Sieve? People v. Bryant and the Rape Shield Law in High-Profile Cases,” Columbia Journal of Law and Social Problems, accessed February 27, 2011, http://www.columbia.edu/cu/jlsp/pdf/Spring2%202006/Haddad10.pdf. Although the Colorado Supreme Court ordered pretrial in camera transcripts of hearings pursuant to Colorado’s rape shield law to remain confidential, an order that was confirmed by the US Supreme Court,Associated Press et. al. v. District Court for the Fifth Judicial District of Colorado, 542 U.S. 1301 (2004), accessed February 27, 2011, http://ftp.resource.org/courts.gov/c/US/542/542.US.1301.04.73.html. the accuser was subjected to so much negative publicity that she eventually refused to cooperate and the prosecution dropped the charges in 2004.

- Do you think rape shield laws should include prohibitions against negative publicity? What are the constitutional ramifications of this particular type of statutory protection?

Check your answer using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

Kobe Bryant Video

Kobe Claims Innocence to Sexual Assault Charges

Kobe Bryant and his attorney discuss the charge of rape filed against Kobe in this video:

Acquaintance Rape

In modern times, rape defendants are frequently known to the victim, which may change the factual situation significantly from stranger rape. Acquaintance rapeThe victim is raped by an acquaintance. Also called date rape., also called date rape, is a phenomenon that could increase a victim’s reluctance to report the crime and could also affect the defendant’s need to use force and the victim’s propensity to physically resist.The National Center for Victims of Crime, “Acquaintance Rape,” Ncvc.org website, accessed February 14, 2011, http://www.ncvc.org/ncvc/main.aspx?dbName=DocumentViewer&DocumentID=32306. Although studies indicate that acquaintance rape is on the rise,The National Center for Victims of Crime, “Acquaintance Rape,” Ncvc.org website, accessed February 14, 2011, http://www.ncvc.org/ncvc/main.aspx?dbName=DocumentViewer&DocumentID=32306. statutes have not entirely addressed the issues presented in an acquaintance rape fact pattern. To adequately punish and deter acquaintance or date rape, rape statutes should punish nonforcible, nonconsensual sexual conduct as severely as forcible rape. Although the majority of states still require forcible sexual intercourse as the rape criminal act element, at least one modern court has rejected the necessity of any force other than what is required to accomplish the sexual intercourse.State of New Jersey in the Interest of M.T.S., 609 A.2d 1266 (1992), accessed February 14, 2011, http://www.4lawnotes.com/showthread.php?t=1886. Some rape statutes have also eliminated the requirement that the defendant use force and punish any sexual intercourse without consent as rape.Utah Code Ann. § 76-5-402(1), accessed February 14, 2011, http://le.utah.gov/~code/TITLE76/htm/76_05_040200.htm.

Spousal Rape

As stated previously, at early common law, a man could not rape his spouse. The policy supporting this exemption can be traced to a famous seventeenth-century jurist, Matthew Hale, who wrote, “[T]he husband cannot be guilty of a rape committed by himself upon his lawful wife, for by their mutual matrimonial consent and contract the wife hath given up herself in this kind unto her husband, which she cannot retract” (Hale, History of Pleas of the Crown, p. 629). During the rape reforms of the 1970s, many states eliminated the marital or spousal rapeThe victim of rape is the defendant’s spouse. exemption, in spite of the fact that the Model Penal Code does not recognize spousal rape. At least one court has held that the spousal rape exemption violates the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because it discriminates against single men without a sufficient government interest.People v. Liberta, 64 N.Y. 2d 152 (1984), accessed February 14, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=1399209540378549726&hl=en&as_sdt=2&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr. In several states that criminalize spousal rape, the criminal act, criminal intent, attendant circumstance, causation, and harm elements are exactly the same as the elements of forcible rape.N. H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 632-A: 5, accessed February 14, 2011, http://www.gencourt.state.nh.us/rsa/html/LXII/632-A/632-A-5.htm. Many states also grade spousal rape the same as forcible rape—as a serious felony.Utah Code Ann. § 76-5-402(2), accessed February 14, 2011, http://le.utah.gov/~code/TITLE76/htm/76_05_040200.htm. Grading of sex offenses is discussed shortly.

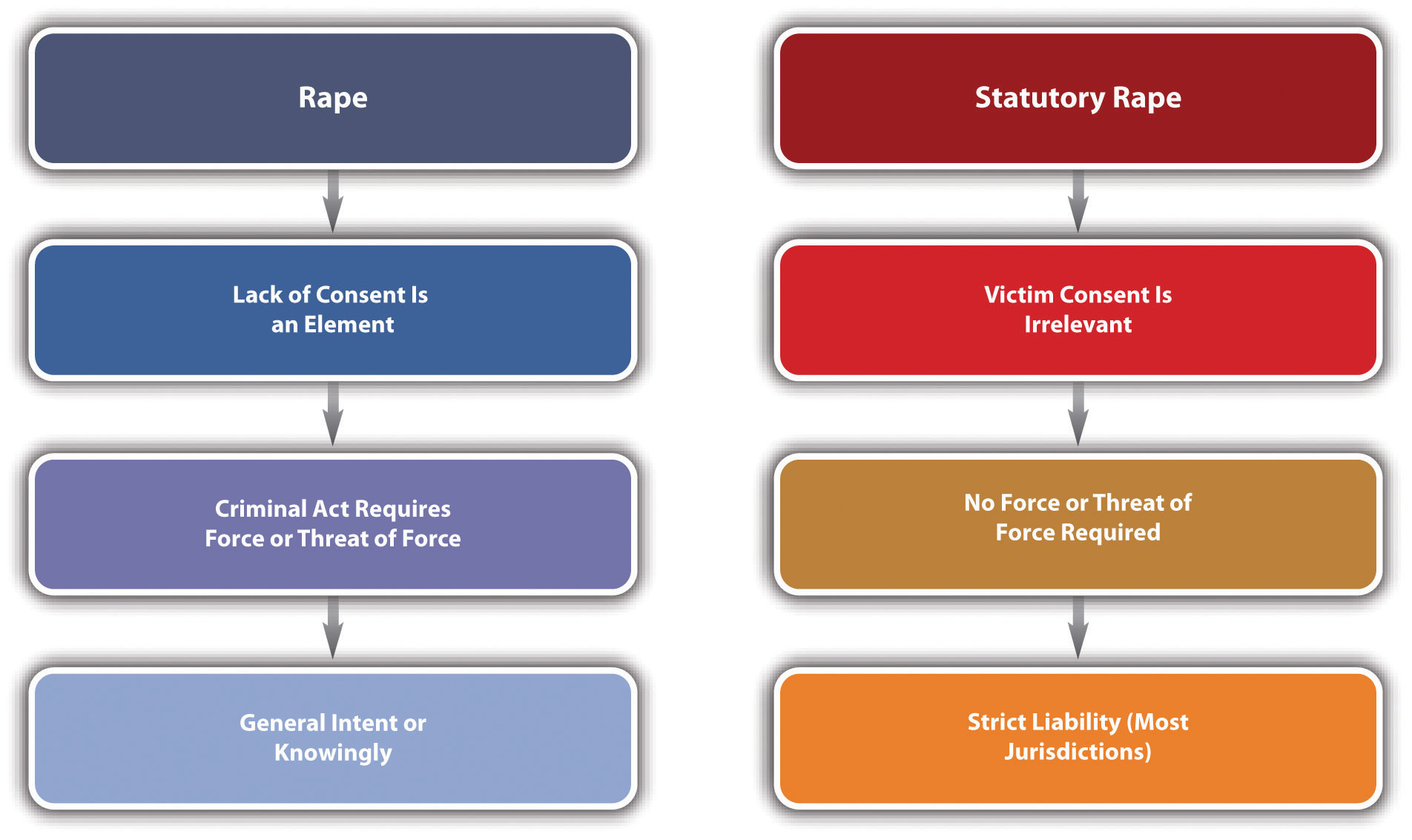

Statutory Rape

Statutory rapeSexual intercourse with a victim younger than the age of legal consent., also called unlawful sexual intercourse, criminalizes sexual intercourse with a victim who is under the age of legal consent. The age of legal consent varies from state to state and is most commonly sixteen, seventeen, or eighteen.Age of Consent Chart for the U.S.-2010, Ageofconsent.us website, accessed February 14, 2011, http://www.ageofconsent.us.

The criminal act element required for statutory rape in many jurisdictions is sexual intercourse, although other types of sexual conduct with a victim below the age of consent are also criminal.US Department of Health and Human Services, “Statutory Rape: A Guide to State Laws and Reporting Requirements,” ASPE.hhs.gov website, accessed February 16, 2011, http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/08/SR/StateLaws/statelaws.shtml. The harm element of statutory rape also varies, although many jurisdictions mirror the harm element required for rape.US Department of Health and Human Services, “Statutory Rape: A Guide to State Laws and Reporting Requirements,” ASPE.hhs.gov website, accessed February 16, 2011, http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/08/SR/StateLaws/statelaws.shtml. The attendant circumstance element required for statutory rape is an underage victim.Cal. Penal Code § 261.5, accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/california/penal/261.5.html. There is no requirement for force by the defendant. Nor is there an attendant circumstance element of lack of consent because the victim is incapable of legally consenting.

In the majority of states, the criminal intent element of statutory rape is strict liability.La. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 14-80, accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.justia.com/louisiana/codes/2009/rs/title14/rs14-80.html. However, a minority of states require reckless or negligent criminal intent, allowing for the defense of mistake of fact as to the victim’s age. If the jurisdiction recognizes mistake of age as a defense, the mistake must be made reasonably, and the defendant must take reasonable measures to verify the victim’s age.Alaska Stat. § 11.41.445(b), accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.justia.com/alaska/codes/2009/title-11/chapter-11-41/article-04/sec-11-41-445. The mistake of age defense can be proven by evidence of a falsified identification, witness testimony that the victim lied about his or her age to the defendant, or even the appearance of the victim.

It is much more common to prosecute males for statutory rape than females. The historical reason for this selective prosecution is the policy of preventing teenage pregnancy.Michael M. v. Superior Court, 450 U.S. 464 (1981), accessed February 15, 2011, http://www.oyez.org/cases/1980-1989/1980/1980_79_1344. However, modern statutory rape statutes are gender-neutral.N.Y. Penal Law § 130.30, accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/new-york/penal/PEN0130.30_130.30.html. This ensures that women, especially women who are older than their sexual partner, are equally subject to prosecution.

Example of Statutory Rape

Gary meets Michelle in a nightclub that only allows entrance to patrons eighteen and over. Gary and Michelle end up spending the evening together, and later they go to Gary’s apartment where they have consensual sexual intercourse. In reality, Michelle is actually fifteen and was using false identification to enter the nightclub. If Gary and Michelle are in a state that requires strict liability for the criminal intent element of statutory rape, Gary can be subject to prosecution for and conviction of this offense if fifteen is under the age of legal consent. If Gary and Michelle are in a state that allows for mistake of age as a defense, Gary could use Michelle’s presence in the nightclub as evidence that he acted reasonably in believing that Michelle was capable of rendering legal consent. If both Gary and Michelle used false identification to enter the nightclub, and both Gary and Michelle are under the age of legal consent, both could be prosecuted for and convicted of statutory rape in most jurisdictions because modern statutory rape statutes are gender-neutral.

Figure 10.3 Comparison of Rape and Statutory Rape

Sodomy and Oral Copulation

As stated previously, some states include rape, sodomyForcible, nonconsensual, penis to anus penetration., and oral copulationForcible, nonconsensual, mouth to sexual organ or anus penetration. in a sexual assault or sexual conduct statute that criminalizes a variety of sexual acts involving penetration.Alaska Stat. § 11.41.410, accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.justia.com/alaska/codes/2009/title-11/chapter-11-41/article-04/sec-11-41-410. In states that distinguish between rape and sodomy, the criminal act element of sodomy is often defined as forcible penis to anus penetration.Cal. Penal Code § 286(a), accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.justia.com/california/codes/2009/pen/281-289.6.html. Typically, the other sodomy elements, including the lack of consent attendant circumstance, criminal intent, causation, and harm, are the same as the elements of rape. Many jurisdictions also grade sodomy the same as rape. Grading is discussed shortly.

Sodomy that is nonforcible but committed with an individual below the age of legal consent is also criminal.Cal. Penal Code § 286(b), accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.justia.com/california/codes/2009/pen/281-289.6.html. As stated previously, the US Supreme Court has held that statutes criminalizing sodomy between consenting adults unreasonably encroach on a right to privacy without a sufficient government interest.Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003), accessed February 15, 2011, http://www.oyez.org/cases/2000-2009/2002/2002_02_102. In some states, consensual nonforcible sodomy is criminal if it is committed in a state penitentiary or local detention facility or jail.Cal. Penal Code § 286(c) (3) (e), accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.justia.com/california/codes/2009/pen/281-289.6.html.

In states that distinguish between rape, sodomy, and oral copulation, the criminal act element of oral copulation is forcible mouth to sexual organ or anus penetration.Cal. Penal Code § 288a, accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/california/penal/288a.html. Typically, the other oral copulation elements, including the lack of consent attendant circumstance, criminal intent, causation, and harm, are the same as the elements of rape. Many jurisdictions also grade oral copulation the same as rape. Grading is discussed shortly.

A few states still criminalize oral copulation with consent.Ala. Code § 13A-6-65, accessed February 15, 2011, http://www.legislature.state.al.us/CodeofAlabama/1975/13A-6-65.htm. Based on the US Supreme Court precedent relating to sodomy, these statutes may be unenforceable and unconstitutional.

Incest

IncestSexual intercourse with a victim who the defendant cannot legally marry because of a family relationship. is also criminal in many jurisdictions. The criminal act element required for incest is typically sexual intercourse.Fla. Stat. Ann. § 826.04, accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/florida/crimes/826.04.html. The attendant circumstance element required for incest is a victim the defendant cannot legally marry because of a family relationship.Del. Code Ann. Tit. 11, § 766, accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.justia.com/delaware/codes/2010/title11/c005-sc02.html. In the majority of jurisdictions, force is not required, and consent is not an attendant circumstance element of incest.Del. Code Ann. Tit. 11, § 766, accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.justia.com/delaware/codes/2010/title11/c005-sc02.html. Thus consent by the victim cannot operate as a defense. If the sexual intercourse with a family member is forcible and nonconsensual, the defendant could be charged with and convicted of rape. The criminal intent element required for incest is typically general intent or knowingly.Fla. Stat. Ann. § 826.04, accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/florida/crimes/826.04.html. The causation and harm elements of incest are generally the same as the causation and harm elements of rape.Fla. Stat. Ann. § 826.04, accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/florida/crimes/826.04.html. However, incest is generally graded lower than forcible rape or sexual assault because force and lack of consent are not required.Del. Code Ann. Tit. 11, § 766, accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.justia.com/delaware/codes/2010/title11/c005-sc02.html.

Example of Incest

Hal and Harriet, brother and sister, have consensual sexual intercourse. Both Hal and Harriet are above the age of legal consent. In spite of the fact that there was no force, threat of force, or fraud, and both parties consented to the sexual act, Hal and Harriet could be charged with and convicted of incest in many jurisdictions, based on their family relationship.

Sex Offenses Grading

Jurisdictions vary when it comes to grading sex offenses. In general, forcible sex crimes involving penetration are graded as serious felonies. Factors that could aggravate grading are gang rape,Fla. Stat. Ann. § 794.023, accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/florida/crimes/794.023.html. the infliction of bodily injury, the use of a weapon, a youthful victim, the commission of other crimes in concert with the sexual offense, or a victim who has mental or intellectual disabilities or who has been compromised by intoxicants.Del. Code Ann. Tit. 11, § 773, accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.justia.com/delaware/codes/2010/title11/c005-sc02.html. The Model Penal Code grades rape as a felony of the second degree unless the actor inflicts serious bodily injury on the victim or another, or the defendant is a stranger to the victim, in which case the grading is elevated to a felony of the first degree (Model Penal Code § 213.1 (1)).

Sexual offenses that do not include penetration are graded lower,N.Y. Penal Law § 130.52, accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/new-york/penal/PEN0130.52_130.52.html. along with offenses that could be consensual.Del. Code Ann. Tit. 11, § 766, accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.justia.com/delaware/codes/2010/title11/c005-sc02.html. Sex offense statutes that criminalize sexual conduct with a victim below the age of legal consent often grade the offense more severely when there is a large age difference between the defendant and the victim, when the defendant is an adult, or the victim is of tender years.Cal. Penal Code § 261.5, accessed February 15, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/california/penal/261.5.html.

Figure 10.4 Diagram of Sex Offenses

Sex Offender Registration Statutes

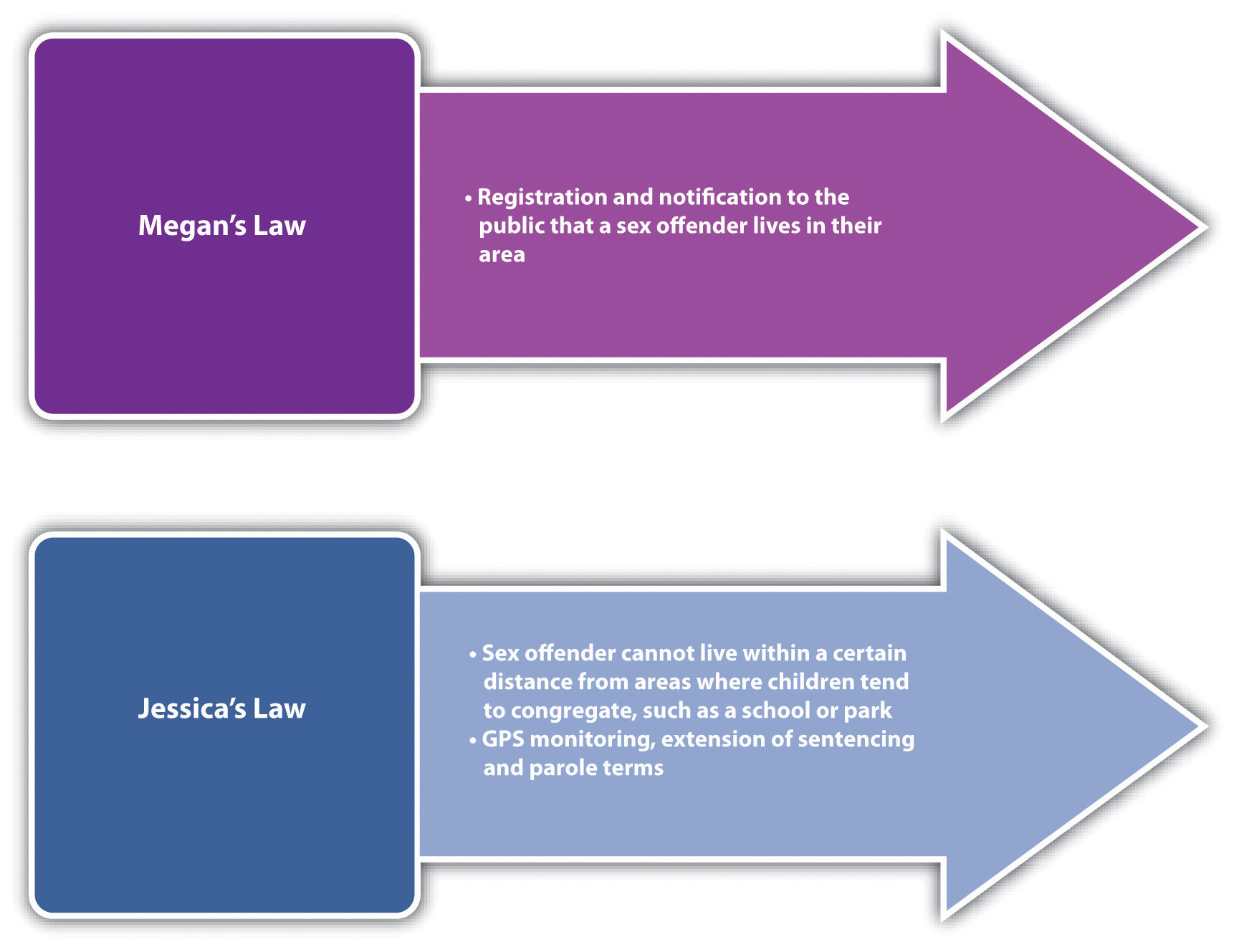

Based on a public awareness that sex offenders often reoffend, many states have enacted some form of Megan’s lawA statute requiring sex offender registration and notification to the public of the location of a sex offender. or Jessica’s lawA statute requiring monitoring of a sex offender., which provide for registration, monitoring, control, and elevated sentencing for sex offenders, including those that harm children. Both laws were written and enacted after high-profile cases with child victims became the subject of enormous media attention. Megan’s and Jessica’s law statutes enhance previously enacted statutes that require the registration of sex offenders with local law enforcement agencies.

Typically, a Megan’s law statute provides for registration and notification to the public that a convicted sex offender lives in their area.42 Pa. C. S. § 9799.1, accessed February 15, 2011, http://www.pameganslaw.state.pa.us. A Jessica’s law statute often includes a stay-away order, mandating that a sex offender cannot live within a certain distance from areas such as a school or park where children tend to congregate. Jessica’s law statutes also provide for GPS monitoring and extend the sentencing and parole terms of child sex offenders.Va. Code Ann. § 19.2-295.2:1, accessed February 15, 2011, http://leg1.state.va.us/cgi-bin/legp504.exe?000+cod+19.2-295.2C1.

Figure 10.5 Diagram of Megan’s and Jessica’s Law Statutes

Key Takeaways

- Common-law rape was a capital offense, did not include rape of a spouse, required extreme resistance by the victim, and required evidence to corroborate a victim’s testimony. Modern statutes do not make rape a capital offense, often criminalize spousal rape, and do not require extreme resistance by the victim or evidence to corroborate the victim’s testimony. At early common law, sodomy was the anal penetration of a man, by a man. Modern statutes make sodomy gender-neutral and only criminalize sodomy without consent.

- The criminal act element required for rape is sexual penetration accomplished with force or threat of force in many jurisdictions.

- The attendant circumstance element required for rape is lack of consent by the victim.

- In many jurisdictions, the victim does not need to resist if the defendant uses force. If the victim is faced with a threat of force rather than force, the victim need not resist if he or she has a subjective fear of serious bodily injury, and this fear is reasonable under the circumstances.

- In modern times, a victim’s testimony does not need to be corroborated by other evidence to convict a defendant of rape.

- The criminal intent element required for rape is general intent or knowingly to commit the criminal act.

- In some jurisdictions, the criminal intent element required for the rape attendant circumstance is negligent intent—providing for a defense of mistake of fact as to the victim’s consent. In other jurisdictions, the criminal intent element required for the rape attendant circumstance is strict liability, which does not allow for the mistake of fact defense.

- The harm element required for rape is penetration, no matter how slight. Ejaculation is not a requirement for rape in most jurisdictions.

- Rape shield laws generally preclude the admission of evidence of the victim’s past sexual conduct in a rape trial, unless it is allowed by a judge at an in camera hearing. Rape shield laws also preclude the admission of evidence of the victim’s style of dress and the victim’s request that the defendant wear a condom to prove victim consent. Some rape shield laws provide that the victim’s testimony need not be corroborated by other evidence to convict the defendant of rape.

- Acquaintance rape often goes unreported and does not necessarily include use of force by the defendant or resistance by the victim.

- States that criminalize spousal rape generally require the same elements for spousal rape as for rape and grade spousal rape the same as rape.

- Statutory rape is generally sexual intercourse with a victim who is under the age of legal consent. Statutory rape does not have the requirement that the intercourse be forcible and does not require the attendant circumstance of the victim’s lack of consent because the victim is incapable of rendering legal consent. In the majority of jurisdictions, the criminal intent element required for statutory rape is strict liability. In a minority of jurisdictions, the criminal intent element required for statutory rape is negligent or reckless intent, providing for a defense of mistake of fact as to the victim’s age.

- Sodomy has the same elements as rape except for the criminal act element, which is often defined as forcible penis to anus penetration, rather than penis to vagina penetration. In addition, in some states sodomy is criminal with consent when it occurs in a state prison or a local detention facility or jail. Oral copulation also has the same elements as rape, except for the criminal act element, which is forcible mouth to sexual organ or anus penetration. Incest is sexual intercourse between family members who cannot legally marry.

- Generally, rape, sodomy, and oral copulation are graded as serious felonies. Factors that enhance grading of sex offenses are penetration, gang rape, bodily injury, the use of a weapon, a victim who has intellectual or mental disabilities or is youthful or intoxicated, and the commission of other crimes in concert with the sex offense. Sex offenses committed with the victim’s consent and without penetration are typically graded lower. If the victim is below the age of consent, a large age difference exists between the defendant and the victim, the defendant is an adult, or the victim is of tender years, grading typically is enhanced.

- Typically, a Megan’s law statute provides for sex offender registration and notification to the public that a convicted sex offender lives in their area. A Jessica’s law statute often includes a stay-away order mandating that a sex offender cannot live within a certain distance from areas such as a school or park where children tend to congregate. Jessica’s law statutes also provide for GPS monitoring and extend the sentencing and parole terms of child sex offenders.

Exercises

Answer the following questions. Check your answers using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

- Jorge and Christina have consensual sexual intercourse. Could this consensual sexual intercourse be criminal? Which crime(s), if any, could exist in this fact pattern?

- Read Toomer v. State, 529 SE 2d 719 (2000). In Toomer, the defendant was convicted of rape after having sexual intercourse with his daughter, who was under the age of fourteen. The jury instruction did not include any requirement for the defendant’s use of force or victim resistance. The defendant appealed and claimed that the prosecution should have proven he used force and the victim’s resistance because the charge was rape, not statutory rape. Did the Supreme Court of South Carolina uphold the defendant’s conviction? Why or why not? The case is available at this link: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=3593808516097562509&q= Toomer+v.+State&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5.

- Read Fleming v. State, 323 SW 3d 540 (2010). In Fleming, the defendant appealed his conviction for aggravated sexual assault of a child under fourteen because he was not allowed to present a mistake of age defense. The defendant claimed that the requirement of strict liability intent as to the age of the victim deprived him of due process of law. Did the Court of Appeals of Texas agree with the defendant? The case is available at this link: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=12908572719333538188&q= %22Scott+v.+State+36+SW+3d+240%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5.

10.2 Assault and Battery

Learning Objectives

- Define the criminal act element required for battery.

- Define the criminal intent element required for battery.

- Define the attendant circumstance element required for battery.

- Define the harm element required for battery.

- Analyze battery grading.

- Distinguish between attempted battery and threatened battery assault.

- Define the elements of attempted battery assault.

- Define the elements of threatened battery assault.

- Analyze assault grading.

AssaultGenerally an attempted battery or a threatened battery, although some states and the Model Penal Code combine assault and battery into one statute called assault. and batteryAn unlawful harmful or offensive touching. are two crimes that are often prosecuted together, yet they are separate offenses with different elements. Although modern jurisdictions frequently combine assault and battery into one statute called assault, the offenses are still distinct and are often graded differently. The Model Penal Code calls both crimes assault, simple and aggravated (Model Penal Code § 211.1). However, the Model Penal Code does not distinguish between assault and battery for grading purposes. This section reviews the elements of both crimes, including potential defenses.

Battery Elements

Battery is a crime that has the elements of criminal act, criminal intent, attendant circumstance, causation, and harm as is discussed in the subsections that follow.

Battery Act

The criminal act element required for battery in most jurisdictions is an unlawful touching, often described as physical contact.720 ILCS § 12-3, accessed February 18, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/illinois/720ilcs5/12-3.html. This criminal act element is what distinguishes assault from battery, although an individual can be convicted of both crimes if he or she commits separate acts supported by the appropriate intent. The defendant can touch the victim with an instrumentality, like shooting the victim with a gun, or can hit the victim with a thrown object, such as rocks or a bottle. The defendant can also touch the victim with a vehicle, knife, or a substance, such as spitting on the victim or spraying the victim with a hose.

Example of Battery Act

Recall from Chapter 1 "Introduction to Criminal Law" an example where Chris, a newly hired employee at McDonald’s, spills steaming-hot coffee on his customer Geoff’s hand. Although Chris did not touch Geoff with any part of his body, he did pour a substance that unlawfully touched Geoff’s body, which could be sufficient to constitute the criminal act element for battery in most jurisdictions.

Battery Intent

The criminal intent element required for battery varies, depending on the jurisdiction. At early common law, battery was a purposeful or knowing touching. Many states follow the common-law approach and require specific intent or purposely, or general intent or knowingly.Fla. Stat. Ann. § 784.03, accessed February 18, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/florida/crimes/784.03.html. Others include reckless intent,K.S.A. § 21-3412, accessed February 18, 2011, http://kansasstatutes.lesterama.org/Chapter_21/Article_34/21-3412.html. or negligent intent.R.I. Gen. Laws § 11-5-2.2, accessed February 18, 2011, http://law.justia.com/rhodeisland/codes/title11/11-5-2.2.html. Jurisdictions that include reckless or negligent intent generally require actual injury, serious bodily injury, or the use of a deadly weapon. The Model Penal Code requires purposely, knowingly, or recklessly causing bodily injury to another, or negligently causing “bodily injury to another with a deadly weapon” (Model Penal Code § 211.1(1) (b)). If negligent intent is not included in the battery statute, certain conduct that causes injury to the victim may not be criminal.

Example of Battery Intent

Review the example with Chris and Geoff in Section 10 "Example of Battery Act". Assume that Chris’s act of pouring hot coffee on Geoff’s hand occurred when Chris attempted to multitask and hand out change at the same moment he was pouring the coffee. Chris’s act of physically touching Geoff with the hot coffee may be supported by negligent intent because Chris is a new employee and is probably not aware of the risk of spilling coffee when multitasking. If the state in which Chris’s spill occurs does not include negligent intent in its battery statute, Chris probably will not be subject to prosecution for this offense. If Chris’s state only criminalizes negligent battery when serious bodily injury occurs, or when causing bodily injury to another with a deadly weapon, Chris will not be subject to prosecution for battery unless the coffee caused a severe burning of Geoff’s hand; hot coffee cannot kill and would probably not be considered a deadly weapon.

Battery Attendant Circumstance

The attendant circumstance element required for battery in most jurisdictions is that the touching occur without the victim’s consent. Thus victim’s consent can operate as a failure of proof or affirmative defense in some factual situations.

Example of Battery Consent Defense

Recall from Chapter 5 "Criminal Defenses, Part 1" the example where Allen tackles Brett during a high school football game, causing Brett to suffer a severe injury. Although Allen intentionally touched Brett, and the result is serious bodily injury, Brett consented to the touching by voluntarily participating in a sporting event where physical contact is frequent. Thus the attendant circumstance element for battery is absent and Allen is probably not subject to prosecution for this offense.

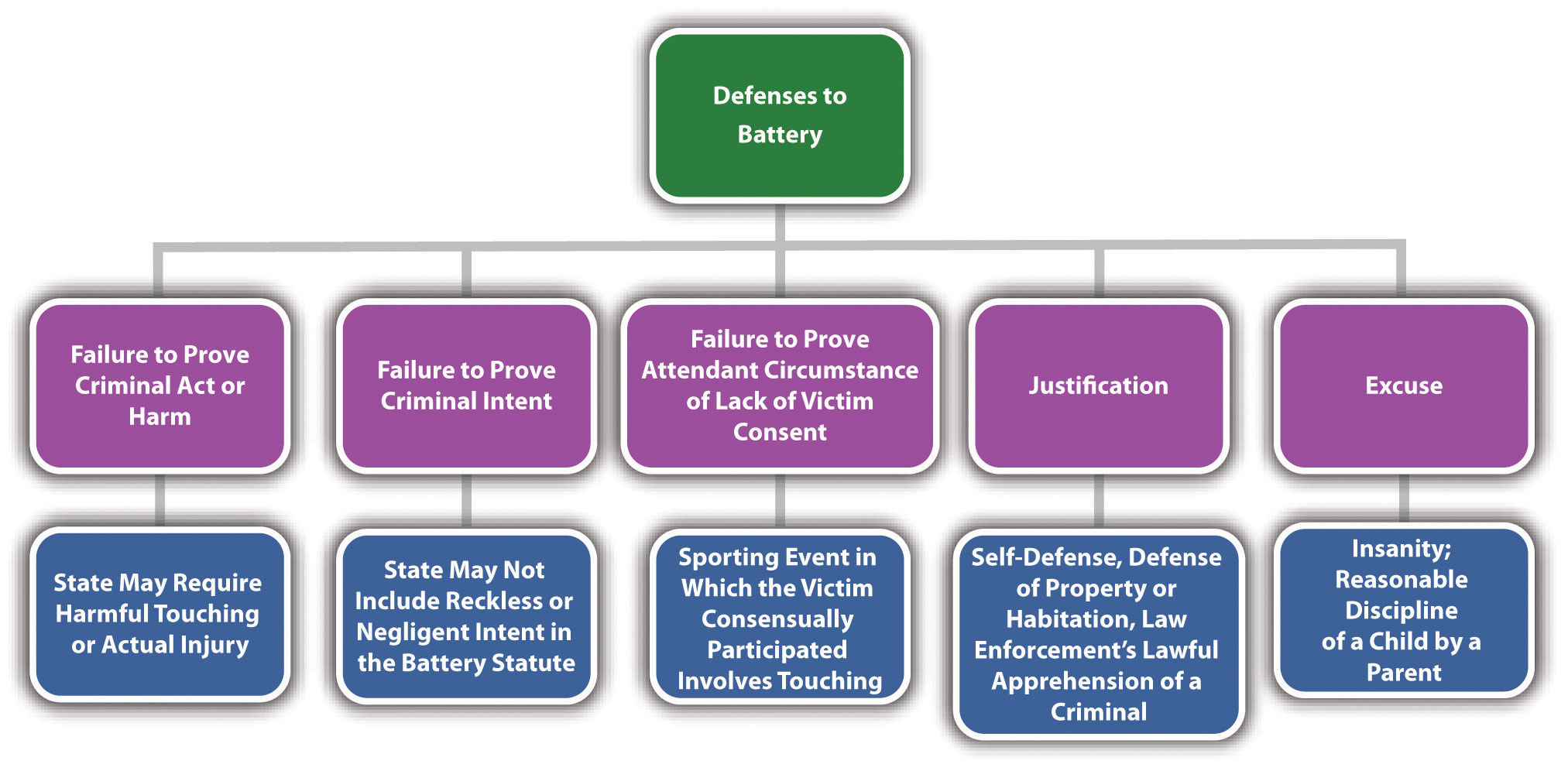

Justification and Excuse Defenses to Battery

In addition to consent, there are also justification and excuse defenses to battery that Chapter 5 "Criminal Defenses, Part 1" and Chapter 6 "Criminal Defenses, Part 2" discuss in detail. To summarize and review, the justification defenses to battery are self-defense, defense of property and habitation, and the lawful apprehension of criminals. An excuse defense to battery that Chapter 6 "Criminal Defenses, Part 2" explores is the insanity defense. One other excuse defense to battery is the reasonable discipline of a child by a parent that is generally regulated by statute and varies from state to state.“United States statutes pertaining to spanking,” Kidjacked.com website, accessed February 18, 2011, http://kidjacked.com/legal/spanking_law.asp.

Battery Causation

The defendant’s criminal act must be the factual and legal cause of the harm, which is defined in Section 10 "Battery Harm".

Battery Harm

The harm requirement for battery varies, depending on the jurisdiction. Many jurisdictions allow for harmful or offensive contact.720 ILCS § 12-3, accessed February 18, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/illinois/720ilcs5/12-3.html. Some jurisdictions require an actual injury to the victim.Ala. Code § 13A-6-21, accessed February 18, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/alabama/criminal-code/13A-6-21.html. The severity of the injury can elevate grading, as is discussed in Section 10 "Battery Grading".

Example of Battery Harm

Review the example in Section 10 "Example of Battery Act" where Chris pours hot coffee on Geoff’s hand. If Chris and Geoff are in a state that requires actual injury to the victim as the harm element of battery, Chris will not be subject to prosecution for this offense unless the hot coffee injures Geoff’s hand. If Chris and Geoff are in a state that allows for harmful or offensive contact, Chris may be charged with or convicted of battery as long as the battery intent element is present, as discussed in Section 10 "Battery Intent".

Figure 10.6 Diagram of Defenses to Battery

Battery Grading

At early common law, battery was a misdemeanor. The Model Penal Code grades battery (called simple assault) as a misdemeanor unless “committed in a fight or scuffle entered into by mutual consent, in which case it is a petty misdemeanor” (Model Penal Code § 211.1(1)). The Model Penal Code grades aggravated battery (called aggravated assault), which is battery that causes serious bodily injury or bodily injury caused by a deadly weapon, as a felony of the second or third degree (Model Penal Code § 211.1(2)). Many states follow the Model Penal Code approach by grading battery that causes offense or emotional injury as a misdemeanor720 ILCS § 12-3, accessed February 18, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/illinois/720ilcs5/12-3.html. and battery that causes bodily injury as a gross misdemeanor or a felony.720 ILCS § 12-4, accessed February 18, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/illinois/720ilcs5/12-4.html. In addition, battery supported by a higher level of intent—such as intent to cause serious bodily injury or intent to maim or disfigure—is often graded higher.Ala. Code § 13A-6-20, accessed February 18, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/alabama/criminal-code/13A-6-20.html. Other factors that can aggravate battery grading are the use of a weapon,R.I. Gen. Laws § 11-5-2, accessed February 18, 2011, http://law.justia.com/rhodeisland/codes/2005/title11/11-5-2.html. the commission of battery during the commission or attempted commission of a serious or violent felony,Ala. Code § 13A-6-20(4), accessed February 18, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/alabama/criminal-code/13A-6-20.html. the helplessness of the victim,Wis. Stat. §§ 940.19(6) (a), 940.19(6) (b), accessed February 18, 2011, http://nxt.legis.state.wi.us/nxt/gateway.dll?f=templates&fn=default.htm&d=stats&jd=ch.%20940. and battery against a teacherWis. Stat. § 940.20(5), accessed February 18, 2011, http://nxt.legis.state.wi.us/nxt/gateway.dll?f=templates&fn=default.htm&d=stats&jd=ch.%20940. or law enforcement officer.Wis. Stat. § 940.20(2), accessed February 18, 2011, http://nxt.legis.state.wi.us/nxt/gateway.dll?f=templates&fn=default.htm&d=stats&jd=ch.%20940.

Assault Elements

Assault is a crime that has the elements of criminal act and intent. A certain type of assault also has a causation and harm element, as is discussed in Section 10 "Threatened Battery Assault".

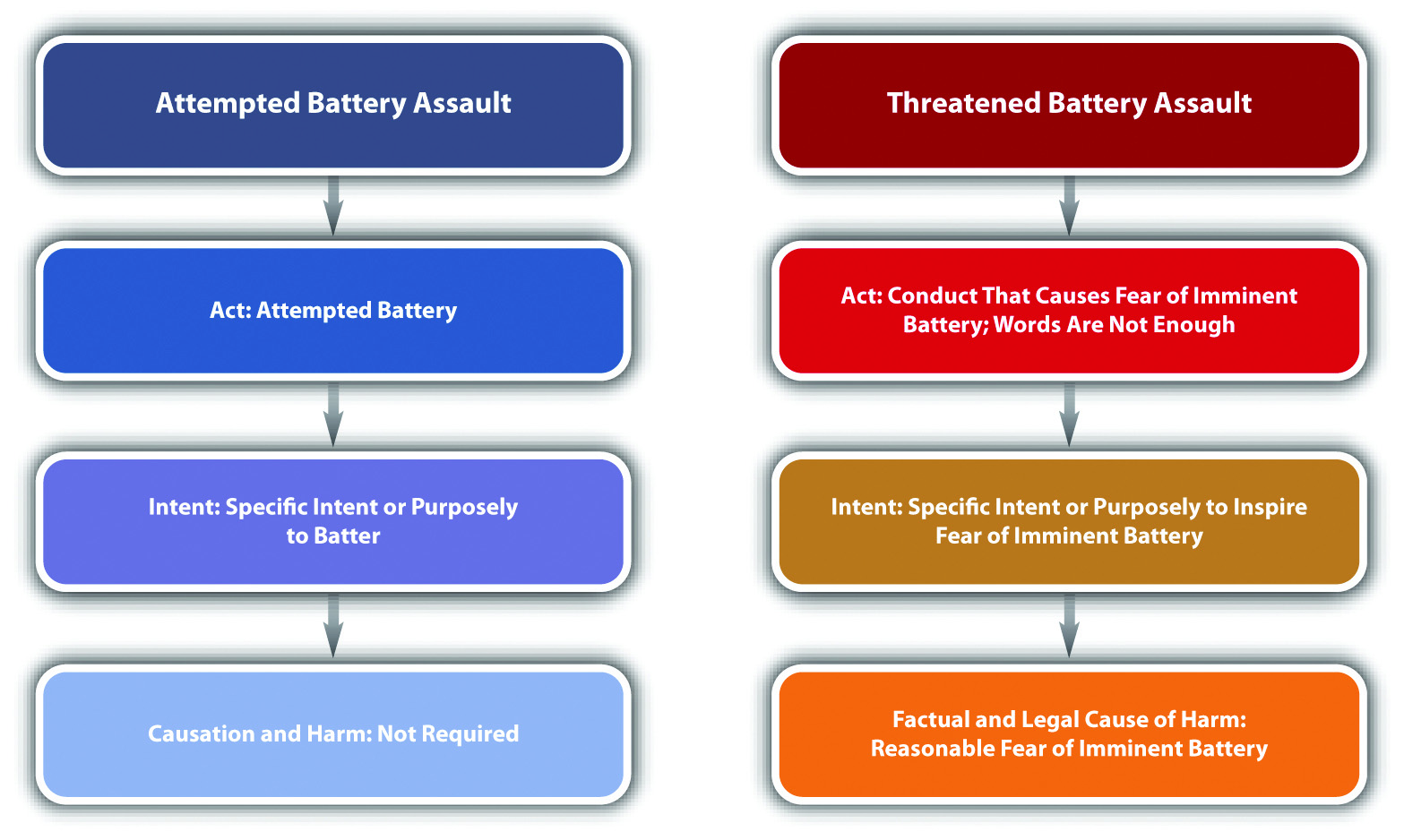

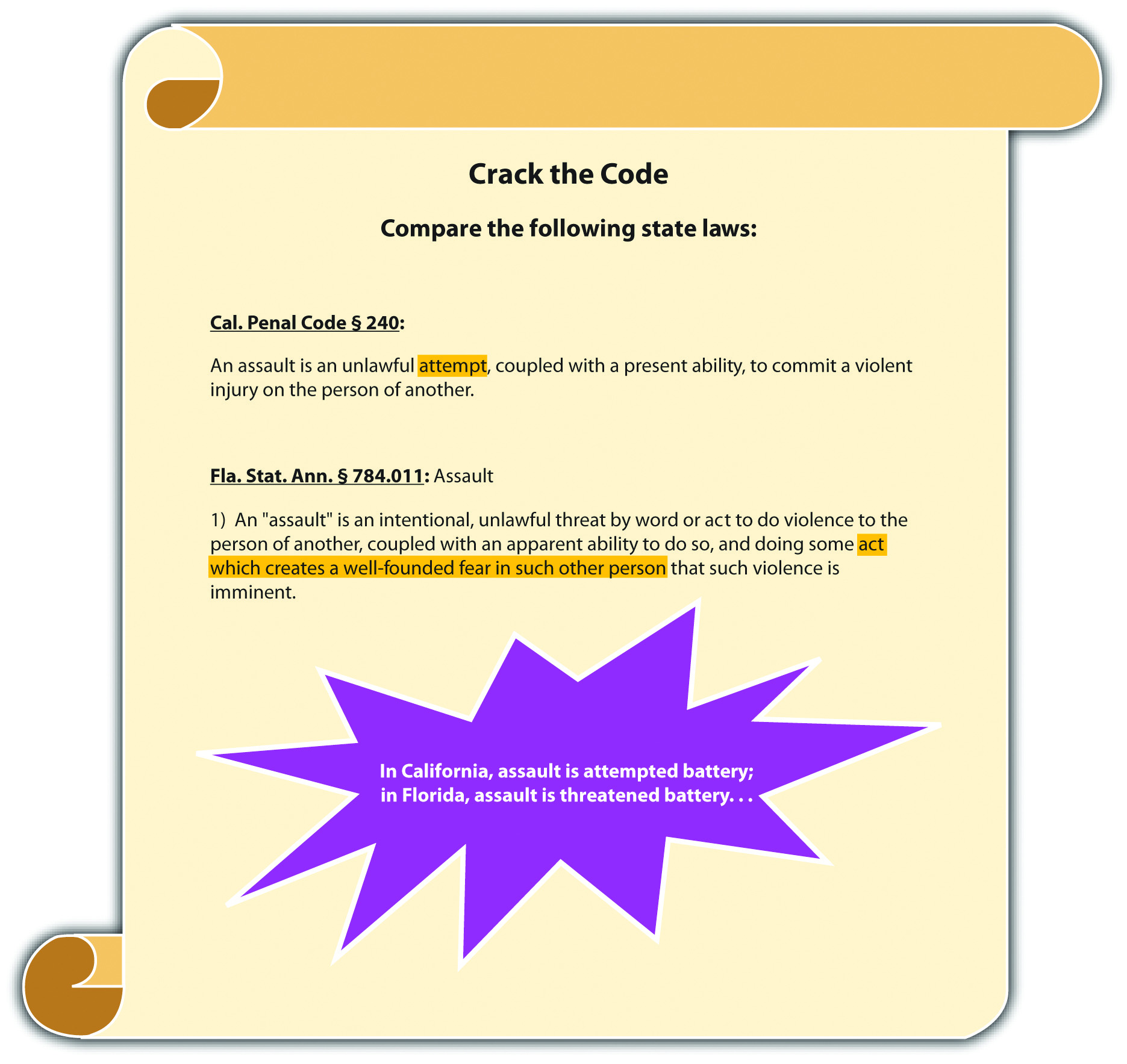

Attempted Battery and Threatened Battery Assault

Two types of assault are recognized. In some jurisdictions, assault is an attempted battery. In other jurisdictions, assault is a threatened battery. The Model Penal Code criminalizes both attempted battery and threatened battery assault (Model Penal Code § 211.1). The elements of both types of assault are discussed in Section 10 "Attempted Battery and Threatened Battery Assault".

Attempted Battery Assault

Attempted battery assault is an assault that has every element of battery except for the physical contact. The elements of attempted battery assaultThe criminal attempt to batter a victim. are criminal act supported by criminal intent. There is no requirement of causation or harm because attempt crimes do not have a harm requirement. Although attempted battery assault should allow for the same defense of consent as battery, this is not as common with assault as it is with battery, so most statutes do not have the attendant circumstance element of lack of consent by the victim.

Attempted Battery Assault Act

The criminal act element required for attempted battery assault is an act that attempts to make physical contact with the victim but falls short for some reason. This could be a thrown object that never hits its target, a gunshot that misses, or a punch that doesn’t connect. In some states, the defendant must have the present ability to cause harmful or offensive physical contact, even though the contact never takes place.Cal. Penal Code § 240, accessed February 19, 2011, http://law.justia.com/california/codes/2009/pen/240-248.html. The present ability requirement is simply an extension of the rule that attempt crimes must progress beyond mere preparation. In the majority of jurisdictions, the criminal act element is measured by the Model Penal Code’s substantial steps test described in detail in Chapter 7 "Parties to Crime".Commonwealth v. Matthews, 205 PA Super 92 (2005), accessed February 19, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=16367791555829234654&q= %22assault%22+%2B+%22conditional+threat%22+%2B+%22not+enough%22&hl= en&as_sdt=2,5. To summarize, the substantial steps test requires the defendant to take substantial steps toward completion of the battery, and the defendant’s actions must be strongly corroborative of the defendant’s criminal purpose (Model Penal Code § 5.01).

Example of Attempted Battery Assault Act

Diana points a loaded pistol at her ex-boyfriend Dan, says, “Prepare to die, Dan,” and pulls the trigger. Fortunately for Dan, the gun malfunctions and does not fire. Diana has probably committed attempted battery assault. Diana took every step necessary toward completion of battery, and her conduct of aiming a pistol at Dan and pulling the trigger was strongly corroborative of her criminal purpose. In addition, it appears that Diana had the present ability to shoot Dan because her gun was loaded. Thus Diana may be charged with and convicted of the offense of attempted battery assault with a deadly weapon. Note that Diana may also be charged with or convicted of attempted murder because it appears that murder intent is present.

Attempted Battery Assault Intent

The criminal intent element required for attempted battery assault is the specific intent or purposely to cause harmful or offensive contact.People v. Nickens, 685 NW 2d 657 (2004), accessed February 19, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=16424953435525763156&hl=en&as_sdt=2&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr. Like all attempt crimes, attempted battery assault cannot be supported by reckless or negligent intent.

Example of Attempted Battery Assault Intent

Change the example in Section 10 "Example of Attempted Battery Assault Act" so that Dan hands Diana a pistol and comments that it is unloaded. Diana says, “Really? Well, then, I can do this!” She thereafter points the gun at Dan and playfully pulls the trigger. The gun malfunctions and does not shoot, although it is loaded. Diana probably cannot be charged with or convicted of attempted battery assault in this case. Although Diana took every step necessary toward making harmful physical contact with Dan, she was acting with negligent, not specific or purposeful, intent. Thus the criminal intent element for attempted battery assault is absent, and Diana could only be charged with a lesser offense such as negligent handling of firearms.

Threatened Battery Assault

Threatened battery assaultThe defendant unlawfully inspires reasonable fear in the victim of a battery. differs from attempted battery assault in that the intent is not to cause physical contact with the victim; the intent is to cause the victim to fear physical contact. Thus threatened battery assault is not an attempt crime and has the additional requirement of causation and harm offense elements.

Threatened Battery Assault Act

The criminal act element required for threatened battery assault is conduct that causes the victim apprehension of immediate harmful or offensive physical contact. In general, words are not enough to constitute the criminal act element required for threatened battery assault.Clark v. Commonwealth, 676 S.E.2d 332 (2009), accessed February 19, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=12317437845803464805&q= %22assault%22+%2B+%22words+are+not+enough%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5. The words must be accompanied by threatening gestures. In addition, a threat of future harm or a conditional threat is not sufficient.Clark v. Commonwealth, 676 S.E.2d 332 (2009), accessed February 19, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=12317437845803464805&q= %22assault%22+%2B+%22words+are+not+enough%22&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5. The physical contact threatened must be unequivocal and immediate. Some jurisdictions still require present ability for threatened battery assault. In others, only apparent ability is necessary; this means the victim must reasonably believe that the defendant can effectuate the physical contact.Fla. Stat. Ann. § 784.011, accessed February 19, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/florida/crimes/784.011.html.

Example of Threatened Battery Assault Act

Change the example given in Section 10 "Example of Attempted Battery Assault Act" so that Dan’s pistol is lying on a table. Diana says to Dan, “If you don’t take me back, I am going to shoot you with your own gun!” At this point, Diana has probably not committed the criminal act element required for threatened battery assault. Diana has only used words to threaten Dan, and words are generally not enough to constitute the threatened battery assault act. In addition, Diana’s threat was conditional, not immediate. If Dan agrees to get back together with Diana, no physical contact would occur. Add to the example, and assume that Dan responds, “Go ahead, shoot me. I would rather die than take you back!” Diana thereafter grabs the gun, points it at Dan, and cocks it. At this point, Diana may have committed the criminal act element required for threatened battery assault. Diana’s threat is accompanied by a serious gesture: cocking a pistol. If the state in which Dan and Diana’s example occurs requires present ability, then the gun must be loaded. If the state requires apparent ability, then Dan must believe the gun is loaded—and if he is wrong, Diana could still have committed the criminal act element required for threatened battery assault.

Threatened Battery Assault Intent

The criminal intent element required for threatened battery assault is the specific intent or purposely to cause fear of harmful or offensive contact.Commonwealth v. Porro, 458 Mass. 526 (2010), accessed February 20, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=13033264667355058927&q= Commonwealth+v.+Porro&hl=en&as_sdt=4,22. This is different from the criminal intent element required for attempted battery assault, which is the specific intent or purposely to cause harmful or offensive contact.

Example of Threatened Battery Assault Intent

Review the example in Section 10 "Example of Threatened Battery Assault Act". Change the example so that the gun that Diana grabs is Diana’s gun, and it is unloaded. Diana is aware that the gun is unloaded, but Dan is not. In this example, Diana probably has the intent required for threatened battery assault. Diana’s act of pointing the gun at Dan and cocking it, after making a verbal threat, indicates that she has the specific intent or purposely to cause apprehension in Dan of imminent harmful physical contact. If Diana is in a state that only requires apparent ability to effectuate the contact, Diana has committed the criminal act supported by criminal intent for threatened battery assault. Note that Diana does not have the proper criminal intent for attempted battery assault if the gun is unloaded. This is because the intent required for attempted battery assault is the intent to cause harmful or offensive contact, which Diana clearly cannot intend to do with an unloaded gun.

Threatened Battery Assault Causation

The defendant’s criminal act must be the factual and legal cause of the harm that is defined in Section 10 "Threatened Battery Assault Harm".

Threatened Battery Assault Harm

The harm element required for threatened battery assault is the victim’s reasonable apprehension of imminent harmful or offensive contact.Commonwealth v. Porro, 458 Mass. 526 (2010), accessed February 20, 2011, http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=13033264667355058927&q= Commonwealth+v.+Porro&hl=en&as_sdt=4,22. Thus the victim’s lack of awareness of the defendant’s criminal act could operate as a failure of proof or affirmative defense in many jurisdictions.

Example of Threatened Battery Assault Harm

Review the example in Section 10 "Example of Threatened Battery Assault Act". Change the example so that after Diana verbally threatens Dan, he shrugs, turns around, and begins to walk away. Frustrated, Diana grabs the gun off of the table and waves it menacingly at Dan’s back. Dan is unaware of this behavior and continues walking out the door. Diana has probably not committed threatened battery assault in this situation. A key component of threatened battery assault is victim apprehension or fear. If Diana silently waves a gun at Dan’s back, it does not appear that she has the specific intent or purposely to inspire fear in Dan of harmful physical contact. In addition, Dan was not cognizant of Diana’s action and did not experience the fear, which is the threatened battery assault harm element. Thus Diana may not be convicted of assault with a deadly weapon in states that criminalize only threatened battery assault. Note that if the gun is loaded, Diana may have committed attempted battery assault in many jurisdictions. Attempted battery assault requires neither intent to inspire fear in the victim nor victim awareness of the defendant’s criminal act. A trier of fact could find that Diana took substantial steps toward committing harmful physical contact when she picked up a loaded gun and waved it at Dan’s back after making a verbal threat. Attempted battery assault has no harm element, so the crime is complete as soon as Diana commits the criminal act supported by criminal intent.

Figure 10.7 Diagram of Assault Elements

Figure 10.8 Crack the Code

Assault Grading

Assault grading is very similar to battery grading in many jurisdictions. As stated previously, many modern statutes follow the Model Penal Code approach and combine assault and battery into one statute, typically called “assault.”Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 13-1203, accessed February 20, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/arizona/criminal-code/13-1203.html. Simple assault is generally a misdemeanor.Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 13-1203, accessed February 20, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/arizona/criminal-code/13-1203.html. Aggravated assault is generally a felony.Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 13-1204, accessed February 20, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/arizona/criminal-code/13-1204.html. Factors that could enhance grading of assault are the use of a deadly weapon and assault against a law enforcement officer, teacher, or helpless individual.Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 13-1204, accessed February 20, 2011, http://law.onecle.com/arizona/criminal-code/13-1204.html.

Table 10.2 Comparing Battery, Attempted Battery, and Threatened Battery Assault

| Crime | Criminal Act | Criminal Intent | Harm | Grading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battery | Unlawful touching | Specific or purposely, general or knowingly, reckless, or negligent | Harmful or offensive physical contact | Simple: misdemeanor Aggravated: felony |

| Attempted battery assault | Substantial steps toward a battery plus present ability | Specific or purposely to commit battery | None required | Simple: misdemeanor Aggravated: felony |

| Threatened battery assault | Conduct that inspires fear of physical contact; words are not enough; may require apparent rather than present ability | Specific or purposely to inspire fear of physical contact | Victim’s reasonable fear of imminent physical contact | Simple: misdemeanor Aggravated: felony |

| Note: Battery could also include the attendant circumstance element of lack of consent by the victim. | ||||

Key Takeaways

- The criminal act element required for battery is an unlawful touching.

- The criminal intent element required for battery can be specific intent or purposely, general intent or knowingly, recklessly, or negligently, depending on the circumstances and the jurisdiction. Jurisdictions that criminalize reckless or negligent battery generally require actual injury, serious bodily injury, or the use of a deadly weapon.

- The attendant circumstance element required for battery is lack of consent by the victim.

- The harm element of battery is physical contact. Jurisdictions vary as to whether the physical contact must be harmful or if it can be harmful or offensive.

- Battery that causes offense or emotional injury is typically graded as a misdemeanor, and battery that causes physical injury is typically graded as a gross misdemeanor or a felony. Factors that can aggravate grading are a higher level of intent, such as intent to maim or disfigure, use of a weapon, committing battery in concert with other serious or violent felonies, and battery against a helpless victim, teacher, or law enforcement officer.

- Attempted battery assault is an attempt crime that does not require the elements of causation or harm. Threatened battery assault requires causation and harm; the victim must experience reasonable fear of imminent physical contact.

- Attempted battery assault requires the criminal act of substantial steps toward commission of a battery and the criminal intent of specific intent or purposely to commit a battery. Because attempted battery assault is an attempt crime, it also generally requires present ability to commit the battery.

- The criminal act element required for threatened battery assault is conduct that inspires reasonable fear in the victim of imminent harmful or offensive physical contact. Words generally are not enough to constitute the criminal act element, nor are conditional threats. However, because the act need only inspire the fear, rather than culminate in a battery, apparent ability to commit the battery is sufficient in many jurisdictions. The criminal intent element required for threatened battery assault is specific intent or purposely to inspire the victim’s reasonable fear. The defendant must also be the factual and legal cause of the harm, which is the victim’s reasonable fear of imminent harmful or offensive physical contact.

- Simple assault is generally graded as a misdemeanor; aggravated assault is generally graded as a felony. Factors that can aggravate grading are the use of a weapon or assault against a law enforcement officer, teacher, or helpless victim.

Exercises

Answer the following questions. Check your answers using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

- Bob and Rick get into an argument after drinking a few beers. Bob swings at Rick with his fist, but Rick ducks and Bob does not hit Rick. Bob swings again with the other hand, and this time he manages to punch Rick in the stomach. Identify the crimes committed in this situation. If Bob only swings once and misses, which crime(s) have been committed?

- Read State v. Higgs, 601 N.W.2d 653 (1999). What criminal act did the defendant commit that resulted in a conviction for battery? Did the Court of Appeals of Wisconsin uphold the defendant’s conviction? Why or why not? The case is available at this link: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=10727852975973050662&q= State+v.+Higgs+601+N.W.2d+653&hl=en&as_sdt=2,5.

- Read Commonwealth v. Henson, 259 N.E.2d 769 (1970). In Henson, the defendant fired blanks at a police officer and was convicted of assault with a deadly weapon. The defendant appealed, claiming that he had no present ability to shoot the police officer because the gun was not loaded with bullets. Did the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts uphold the defendant’s conviction? The case is available at this link: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=11962310018051202223&hl=en&as_sdt=2002&as_vis=1.

10.3 Domestic Violence and Stalking

Learning Objectives

- Identify the individuals covered by domestic violence statutes.

- Identify some of the special features of domestic violence statutes.

- Define the criminal act element required for stalking.

- Define the criminal intent element required for stalking, and compare various statutory approaches to stalking criminal intent.

- Define the harm element required for stalking, and compare various statutory approaches to ascertaining harm.

- Analyze stalking grading.

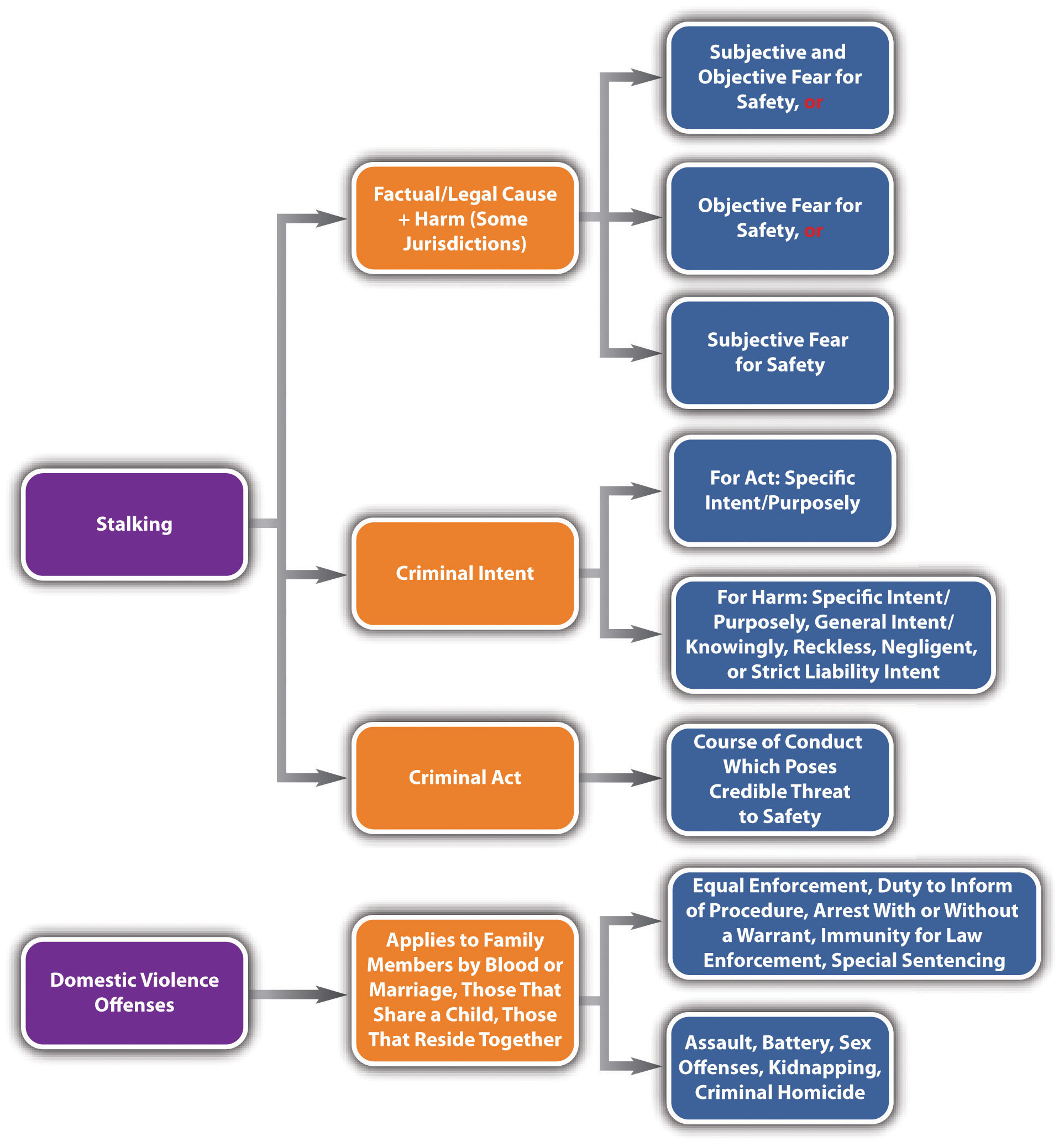

Domestic violenceCriminal conduct between family members or those who reside together. and stalkingA course of conduct that poses a credible threat to safety or damage to property, including following, harassing, and pursuing the victim. are modern crimes that respond to societal problems that have escalated in recent years. Domestic violence statutes are drafted to address issues that are prevalent in crimes between family members or individuals living in the same household. Stalking generally punishes conduct that is a precursor to assault, battery, or other crimes against the person, as is explored in Section 10.3 "Domestic Violence and Stalking".

Domestic Violence

Domestic violence statutes generally focus on criminal conduct that occurs between family members. Although family cruelty or interfamily criminal behavior is not a new phenomenon, enforcement of criminal statutes against family members can be challenging because of dependence, fear, and other issues that are particular to the family unit. In addition, historical evidence indicates that law enforcement can be reluctant to get involved in family disputes and often fails to adequately protect victims who are trapped in the same residence as the defendant. Specific enforcement measures that are crafted to apply to defendants and victims who are family members are an innovative statutory approach that many jurisdictions are beginning to adopt. In general, domestic violence statutes target crimes against the person, for example, assault, battery, sex offenses, kidnapping, and criminal homicide.

Domestic Violence Statutes’ Characteristics

The purpose of many domestic violence statutes is equal enforcement and treatment of crimes between family members and maximum protection for the domestic violence victim.RCW § 10.99.010, accessed February 21, 2011, http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=10.99.010. Domestic violence statutes focus on individuals related by blood or marriage, individuals who share a child, ex-spouses and ex-lovers, and individuals who reside together.Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 13-3601(A), accessed February 21, 2011, http://www.azleg.state.az.us/ars/13/03601.htm. Domestic violence statutes commonly contain the following provisions:

- Special training for law enforcement in domestic issuesRCW § 10.99.030, accessed February 21, 2011, http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=10.99.030.

- Protection of the victim by no-contact orders and nondisclosure of the victim’s residence addressRCW § 10.99.040, accessed February 21, 2011, http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=10.99.040.