This is “Nature of the Liability Exposure”, section 12.1 from the book Enterprise and Individual Risk Management (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

12.1 Nature of the Liability Exposure

Learning Objectives

In this section we elaborate on the following:

- How legal liability is defined and determined

- Types of monetary compensation for liability damages

- The role of negligence in liability

- Defenses against liability

- Modifications to liability, as they are generally determined

Legal liabilityThe responsibility, based in law, to right some wrong done to another person or organization. is the responsibility, based in law, to right some wrong done to another person or organization. Several aspects of this definition deserve further discussion. One involves the remedy of liability. A remedyCompensation for a person who has been harmed in some way. is compensation for a person who has been harmed in some way. A person who has been wronged or harmed may ask the court to remedy or compensate him or her for the harm. Usually, this will involve monetary compensation, but it could also involve some behavior on the part of the person who committed the wrong, or the tortfeasorA person who commits a wrong.. For example, someone whose water supply has been contaminated by a polluting business may request an injunction against the business to force the cessation of pollution. A developer who is constructing a building in violation of code may be required to halt construction based on a liability lawsuit.

When monetary compensation is sought, it can take one of several forms. Special damagesCompensation for harms that generally are easily quantifiable into dollar measures. (or economic damages) compensate for those harms that generally are easily quantifiable into dollar measures. These include medical expenses, lost income, and repair costs of damaged property. Those harms that are not specifically quantifiable but that require compensation all the same are called general damagesCompensation for harms that are not specifically quantifiable but that require compensation all the same. (or noneconomic damagesCompensation for harms that are not specifically quantifiable but that require compensation all the same.). Examples of noneconomic or general damages include pain and suffering, mental anguish, and loss of consortium (companionship). The third type of monetary liability award is punitive damages, which was discussed in Note 10.25 "Are Punitive Damages out of Control?" in Chapter 10 "Structure and Analysis of Insurance Contracts". In this chapter, we will continue to discuss the controversy surrounding the use of punitive damages. Punitive damagesAwards intended to punish an offender for exceptionally undesirable behavior. are considered awards intended to punish an offender for exceptionally undesirable behavior. Punitive damages are intended not to compensate for actual harm incurred but rather to punish.

A second important aspect of the definition of liability is that it is based in law. In this way, liability differs from other exposures because it is purely a creation of societal rules (laws), which reflect social norms. As a result, liability exposures differ across societies (nations) over time. In the United States, liability is determined by the courts and by laws enacted by legislatures.

The risk of liability is twofold. Not only may you become liable to someone else and suffer loss, but someone else may become liable to you and have to pay you. You need to know about both sides of the coin, so to speak. Your financial well-being or that of your organization can be adversely affected by your responsibility to others or by your failure to understand their responsibility to you. If you are the party harmed, you would be the plaintiffThe party harmed in litigation. in litigation. The party being sued in litigation is the defendantThe party being sued in litigation.. In some circumstances the parties will be both plaintiffs and defendants.

Basis of Liability

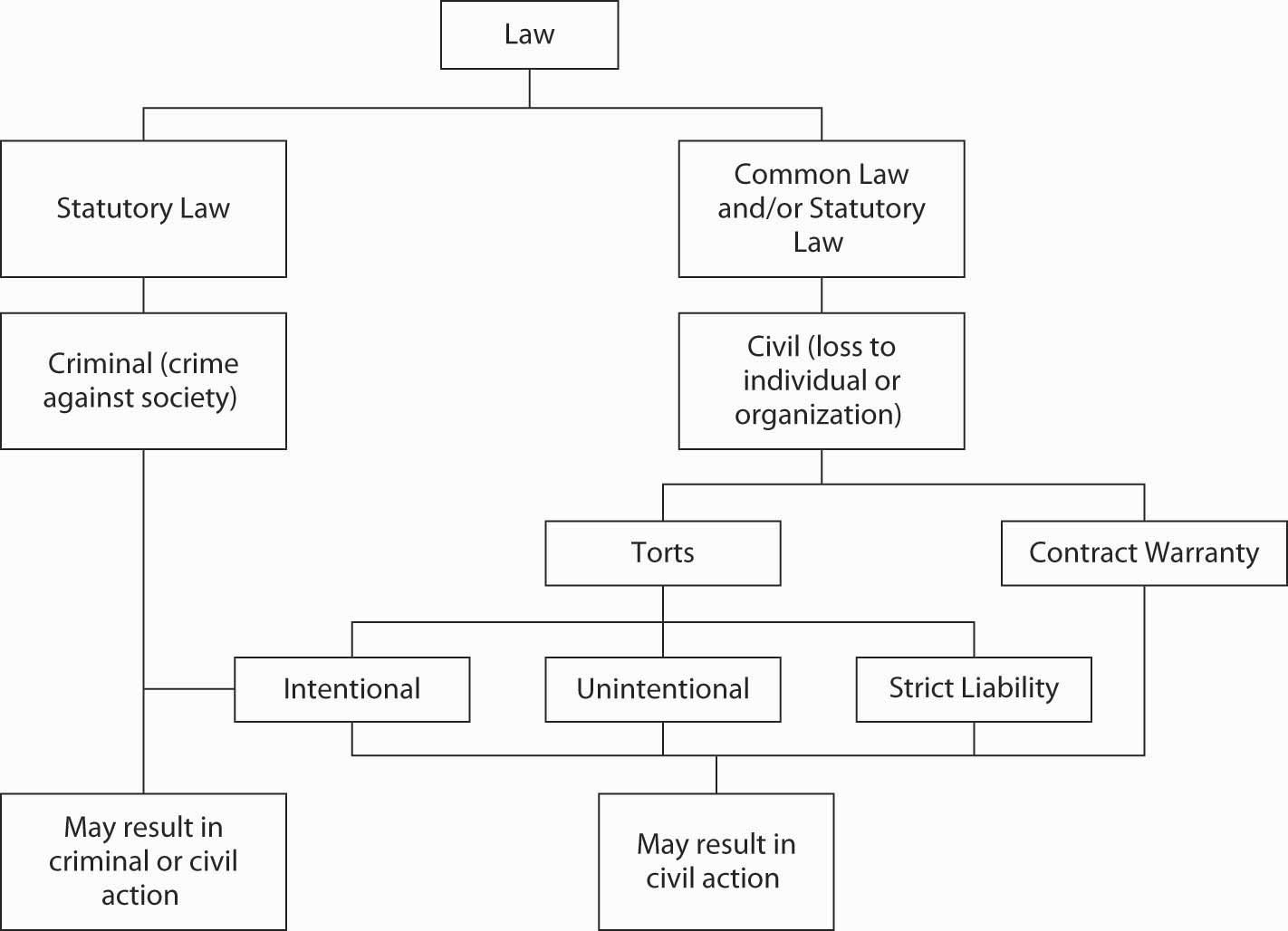

The liability exposure may arise out of either statutory or common law, as shown in Figure 12.2 "Basis of Liability Risk". Statutory lawThe body of written law created by legislatures. is the body of written law created by legislatures. Common lawBody of law based on custom and court decisions., on the other hand, is based on custom and court decisions. In evolving common law, the courts are guided by the doctrine of stare decisis (Latin for “to stand by the decisions”). Under the doctrine of stare decisisPrinciple that once a court decision is made in a case with a given set of facts, the courts tend to adhere to the principle thus established and apply it to future cases involving similar facts., once a court decision is made in a case with a given set of facts, the courts tend to adhere to the principle thus established and apply it to future cases involving similar facts. This practice provides enough continuity of decision making that many disputes can be settled out of court by referring to previous decisions. Some people believe that in recent years, as new forms of liability have emerged, continuity has not been as prevalent as in the past.

Figure 12.2 Basis of Liability Risk

As illustrated in Figure 12.2 "Basis of Liability Risk", the field of law includes criminal law and civil law. Criminal lawLaw concerned with acts that are contrary to public policy (crimes), such as murder or burglary. is concerned with acts that are contrary to public policy (crimes), such as murder or burglary. Civil lawLaw that deals with acts that are not against society as a whole but rather cause injury or loss to an individual or organization., in contrast, deals with acts that are not against society as a whole, but rather cause injury or loss to an individual or organization, such as carelessly running a car into the side of a building. A civil wrong may also be a crime. Murder, for instance, attacks both society and individuals. Civil law has two branches: one concerned with the law of contracts and the other with the law of torts (explained in the next paragraph). Civil liability may stem from either contracts or torts.

Contractual liabilityWhen the terms of a contract are not carried out as promised by either party to the contract. occurs when the terms of a contract are not carried out as promised by either party to the contract. When you sign a rental agreement for tools, for example, the agreement may provide that the tools will be returned to the owner in good condition, ordinary wear and tear excepted. If they are stolen or damaged, you are liable for the loss. As another example, if you offer your car for sale and assure the buyer that it is in perfect condition, you have made a warranty. A warrantyA guarantee that property or service sold is of the condition represented by the seller. is a guarantee that property or service sold is of the condition represented by the seller. If the car is not in perfect condition, you may be liable for damages because of a breach of warranty. This is why some sellers offer goods for sale on an “as is” basis; they want to be sure there is no warranty.

A tortA private or civil wrong or injury, other than breach of contract, for which the court will provide a remedy in the form of an action for damages. is “a private or civil wrong or injury, other than breach of contract, for which the court will provide a remedy in the form of an action for damages.”H. J. Black, Black’s Law Dictionary, 5th ed. (St. Paul, MI: West Publishing Company, 1983), 774. That is, all civil wrongs, except breach of contract, are torts. A tort may be intentional if it is committed for the purpose of injuring another person or the person’s property, or it may be unintentional. Examples of intentional torts include libel, slander, assault, and battery, as you will see in the contracts provided as appendixes at the end of this book. While a risk manager may have occasion to be concerned about liability arising from intentional torts, the more frequent source of liability is the unintentional tort. By definition, unintentional torts involve negligence.

If someone suffers bodily injury or property damage as a result of your negligence, you may be liable for damages. Negligence refers to conduct or behavior. It may be a matter of doing something you should not do, or failing to do something you should do. NegligenceFailure to act reasonably, where such failure to act causes harm to others. can be defined as a failure to act reasonably, and that failure to act causes harm to others. It is determined by proving the existence of four elements (sometimes people use three, combining the last two into one). These four elements are the following:

- A duty to act (or not to act) in some way

- Breach of that duty

- Damage or injury to the one owed the duty

- A causal connection, called a proximate causeA causal connection., between the breach of a duty and the injury

An example may be helpful. When a person operates an automobile, that person has a duty to obey traffic rules and to drive appropriately for the given conditions. A person who drives while drunk, passes in a no passing zone, or drives too fast on an icy road (even if within set speed limits) has breached the duty to drive safely. If that person completes the journey without an incident, no negligence exists because no harm occurred. If, however, the driver causes an accident in which property damage or bodily injury results, all elements of negligence exist, and legal liability for the resulting harm likely will be placed on the driver.

A difficult aspect of proving negligence is showing that a breach of duty has occurred. Proof requires showing that a reasonable and prudent person would have acted otherwise. Courts use a variety of methods to assess reasonableness. One is a cost-benefit approach, which holds behavior to be unreasonable if the discounted value of the harm is more than the cost to avoid the harmThis was first stated explicitly by Judge Learned Hand in U.S. v. Carroll Towing Co., 159 F. 2d 169 (1947).—that is, if the present value of the possible loss is greater than the expense required to avoid the loss. In this way, courts use an efficiency argument to determine the appropriateness of behavior.

A second difficult aspect of proving negligence is to show a proximate cause between the breach of duty and resulting harm. Proximate cause has been referred to as an unbroken chain of events between the behavior and harm. The intent is to find the relevant cause through assessing liability. The law is written to encourage behavior with consideration of its consequences.

Liability will not be found in all the circumstances just described. The defendant has available a number of defenses, and the burden of proof may be modified under certain situations.

Defenses

A number of defenses against negligence exist, with varying degrees of acceptance. A list of defenses is shown in Table 12.1 " Defenses against Liability". One is assumption of risk. The doctrine of assumption of riskDoctrine that holds that if the plaintiff knew of the dangers involved in the act that resulted in harm, but chose to act in that fashion nonetheless, the defendant will not be held liable. holds that if the plaintiff knew of the dangers involved in the act that resulted in harm but chose to act in that fashion nonetheless, the defendant will not be held liable. An example would be a bungee cord jumper who is injured from the jump. One could argue that a reasonable person would know that such a jump is very dangerous. If applicable, the assumption of risk defense bars the plaintiff from a successful negligence suit. The doctrine was particularly important in the nineteenth century for lawsuits involving workplace injuries, where employers would defend against liability by claiming that workers knew of job dangers. With workers’ compensation statutes in place today, the use of assumption of risk in this way is of little importance, as you will see in Chapter 1 "The Nature of Risk: Losses and Opportunities". Many states have also abolished the assumption of risk doctrine in automobile liability cases, disallowing the defense that a passenger assumed the risk of loss if the driver was known to be dangerous or the car unsafe.

Table 12.1 Defenses against Liability

|

A second defense found in just a few states is the doctrine of contributory negligenceSituation that disallows any recovery by the plaintiff if the plaintiff is shown to be negligent to any degree in not avoiding the relevant harm., which disallows any recovery by the plaintiff if the plaintiff is shown to be negligent to any degree in not avoiding the relevant harm. Thus, the motorist who was only slightly at fault in causing an accident may recover nothing from the motorist who was primarily at fault. In practice, a judge or jury is unlikely to find a plaintiff slightly at fault where contributory negligence applies. Theoretically, however, the outcome is possible.

The trend today is a shift away from the use of contributory negligence. Instead, most states follow the doctrine of comparative negligence. In comparative negligenceSituation in which the court compares the relative negligence of the parties and apportions recovery on that basis., the court compares the relative negligence of the parties and apportions recovery on that basis. At least two applications of the comparative negligence rule may be administered by the courts. Assume that, in the automobile example, both motorists experienced damages of $100,000, and that one motorist was 1 percent at fault, the other 99 percent at fault. Under the partial comparative negligenceRule under which only the individual less than 50 percent at fault in causing harm receives compensation. rule, only the individual less than 50 percent at fault in causing harm receives compensation. The compensation equals the damages multiplied by the percentage not at fault, or $99,000 ($100,000 × .99) in our example. Under the complete comparative negligenceRule under which both parties share damage in relation to their levels of responsibility for fault. rule, damages are shared by both parties in relation to their levels of responsibility for fault. The motorist who was 1 percent at fault still receives $99,000, but must pay the other motorist $1,000 ($100,000 × .01), resulting in a net compensation of $98,000. Because few instances exist when a party is completely free of negligence, and because society appears to prefer that injured parties be compensated, comparative negligence has won favor over contributory negligence. An important question, though, is how the relative degrees of fault are determined. Generally, a jury is asked to make such an estimate based on the testimony of various experts. Examples of the application of contributory and comparative negligence are shown in Table 12.2 " Contributory and Comparative Negligence".

Table 12.2 Contributory and Comparative Negligence

| Assume that two drivers are involved in an automobile accident. Their respective losses and degrees of fault are as follows: | ||

| Losses ($) | Degree of Fault | |

| Dan | 16,000 | .60 |

| Kim | 22,000 | .40 |

| Their compensation would be determined as follows: | |||

| Contributory | Partial Comparative* | Complete Comparative** | |

| Dan | 0 | 0 | 7,200 |

| Kim | 0 | 13,200 | 13,200 |

| * Only when party is less at fault than the other is compensation available. Here Dan’s fault exceeds Kim’s. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ** Complete comparative negligence forces an offset of payment. Kim would receive $6,000 from Dan ($13,200 ± 7,200). | |||

Last clear chance is a further defense to liability. Under the last clear chanceDoctrine under which a plaintiff who assumed the risk or contributed to an accident through negligence is not barred from recovery if the defendant had the opportunity to avoid the accident but failed to do so. doctrine, a plaintiff who assumed the risk or contributed to an accident through negligence is not barred from recovery if the defendant had the opportunity to avoid the accident but failed to do so. For instance, the motorist who could have avoided hitting a jaywalker but did not had the last clear chance to prevent the accident. The driver in this circumstance could not limit liability by claiming negligence on the part of the plaintiff. Today, the doctrine has only minor application. It may be used, however, when the defendant employs the defense of contributory negligence against the plaintiff.

Last in this list of defenses is immunity. Where immunityA complete defense against liability because of status as a protected entity, professional, or other party. applies, the defendant has a complete defense against liability merely because of status as a protected entity, professional, or other party. For example, governmental entities in the United States were long protected under the doctrine of sovereign immunity. Sovereign immunity held that governments could do no wrong and therefore could not be held liable. That doctrine has lost strength in most states, but it still exists to some degree in certain circumstances. Other immunities extend to charitable organizations and family members. Like sovereign immunity, these too have lost most of their shield against liability.

Modifications

Doctrines of defense are used to prevent a successful negligence (and sometimes strict liability) lawsuit. Other legal doctrines modify the law to assist the plaintiff in a lawsuit. Some of these are discussed here and are listed in Table 12.3 " Modifications of Negligence".

Table 12.3 Modifications of Negligence

|

Rules of negligence hold that an injured person has the burden of proof; that is, he or she must prove the defendant’s negligence in order to receive compensation. Courts adhere to these rules unless reasons exist to modify them. In some situations, for example, the plaintiff cannot possibly prove negligence. The court may then apply the doctrine of res ipsa loquiturDoctrine that shifts the burden of proof to the defendant. (“the thing speaks for itself”), which shifts the burden of proof to the defendant. The defendant must prove innocence. The doctrine may be used upon proof that the situation causing injury was in the defendant’s exclusive control, and that the accident was one that ordinarily would not happen in the absence of negligence. Thus, the event “speaks for itself.”

Illustrations of appropriate uses of res ipsa loquitur may be taken from medical or dental treatment. Consider the plaintiff who visited a dentist for the extraction of wisdom teeth and was given a general anesthetic for the operation. Any negligence that may have occurred during the extraction could not be proved by the plaintiff, who could not possibly have observed the negligent act. If, upon waking, the plaintiff has a broken jaw, res ipsa loquitur might be employed.

Doctrines with similar purposes to res ipsa loquitur may be available when a particular defendant cannot be identified. Someone may be able to prove by a preponderance of evidence, for example, that a certain drug caused an adverse reaction, but that person may be unable to prove which company manufactured the particular bottle consumed. Courts may shift the burden of proof to the defendants in such a circumstance.Two such theories are called enterprise liability and market share liability. Both rely on the plaintiff’s inability to prove which of several possible companies manufactured the particular product causing injury when each company makes the same type of product. Under either theory, the plaintiff may successfully sue a “substantial” share of the market without proving that any one of the defendants manufactured the actual product that caused the harm for which compensation is sought.

Liability may also be strict (or, less often, absolute) rather than based on negligence. That is, if you have property or engage in an activity that is considered ultra-dangerous to others, you may become liable on the basis of strict liabilityLiability without regard to fault. without regard to fault. In some states, for example, the law holds owners or operators of aircraft liable with respect to damage caused to persons or property on the ground, regardless of the reasonableness of the owner’s or operator’s actions. Similarly, if you dam a creek on your property to build a lake, you will be liable in most situations for injury or damage caused if the dam collapses and floods the area below. In product liability, discussed later in this chapter, a manufacturer may be liable for harm caused by use of its product, even if the manufacturer was reasonable in producing it. Thus, the manufacturer is strictly liable.

In some jurisdictions, the owner of a dangerous animal is liable by statute for any harm or damage caused by the animal. Such liability is a matter of law. If you own a pet lion, you may become liable for damages regardless of how careful you are. Similarly, the responsibility your employer has in the event you are injured or contract an occupational disease is based on the principle of liability without fault.Workers’ compensation is discussed in Chapter 1 "The Nature of Risk: Losses and Opportunities". Both situations involve strict liability.

In addition, liability may be vicarious. That is, the vicarious liabilitySituation in which the liability of one person may be based on the tort of another. of one person may be based on the tort of another, particularly in an agency relationship. An employer, for example, may be liable for damages caused by the negligence of an employee who is on duty. Such an agency relationship may result in vicarious liability for the principal (employer) if the agent (employee) commits a tort while acting as an agent. The principal need not be negligent to be liable under vicarious liability. The employee who negligently fails to warn the public of slippery floors while waxing them, for instance, may cause his or her employer to be liable to anyone injured by falling. Vicarious liability will not, however, shield the wrongdoer from liability. It merely adds a second potentially liable party. The employer and employee in this case may both be liable. Recall the case of vanishing premiums described in Chapter 9 "Fundamental Doctrines Affecting Insurance Contracts". Insurers were found to have liability because of the actions of their agents.

A controversial modification to negligence is the use of the joint and several liability doctrine. Joint and several liabilitySituation that exists when a plaintiff is permitted to sue any of several defendants individually for the full harm incurred. exists when the plaintiff is permitted to sue any of several defendants individually for the full harm incurred. Alternatively, the plaintiff may sue all or a portion of the group together. Under this application, a defendant may be only slightly at fault for the occurrence of the harm, but totally responsible for paying for it. The classic example comes from a case in which a Disney World patron was injured on a bumper car ride.Walt Disney World Co. v. Wood, 489 So. 2d 61 (Fla. 4th Dist. Ct. Appl. 1986), upheld by the Florida Supreme Court (515 So. 2d 198, 1987). The plaintiff was found 14 percent contributory at fault; another park patron was found 85 percent at fault; Disney was found 1 percent at fault. Because of the use of the joint and several liability doctrine, Disney was required to pay 86 percent of the damages (the percentage that the plaintiff was not at fault). Note that this case is an exceptional use of joint and several liability, not the common use of the doctrine.

Key Takeaways

In this section you studied the general notion of liability and the related legal aspects thereof:

- Legal liability is the responsibility to remedy a wrong done to another

- Special damages, general damages, and punitive damages are the types of monetary remedies applied to liability

- Liability exposure arises out of statutory law or common law and cases are heard in criminal or civil court

- Negligent actions may result in liability for losses suffered as a result

- Liability through negligence is proven through existence of a duty to act (or not act) in some way, breach of the duty, injury to one owed the duty, and causal connection between breach of duty and injury

- Defenses against liability include assumption of risk, contributory negligence, comparative negligence, last clear chance, and immunity

- Modifications to help the plaintiff in a liability case include res ipsa loquitur, strict liability, vicarious liability, and joint and several liability

Discussion Questions

- Distinguish between criminal law and civil law.

- Distinguish between strict liability and negligence-based liability.

- What is the impact of res ipsa loquitur on general doctrines of liability? What seems to be the rationale for permitting use of this modification?

- Considering the factors involved in establishing responsibility for damages based on negligence, what do you think is your best defense against such a suit?