This is “Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892)”, section 7.6 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

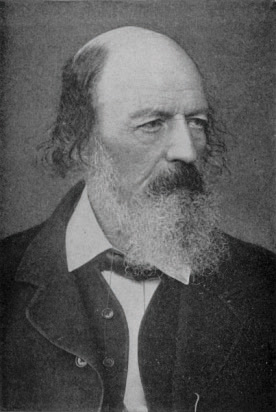

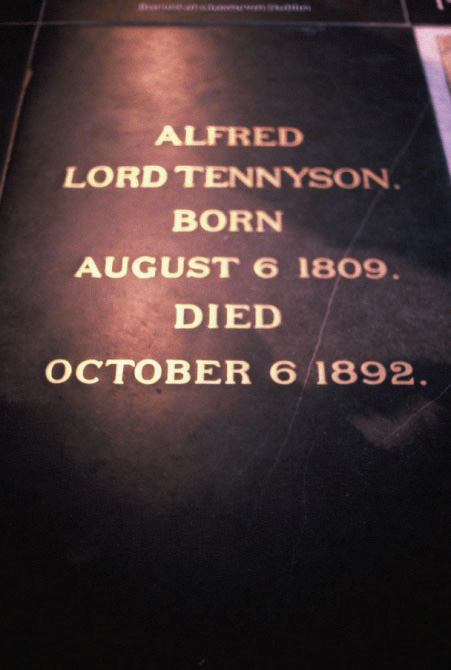

7.6 Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Categorize works by Tennyson as illustrations of conflicts of the Victorian Age.

- Identify parallels between Tennyson’s Arthurian works and Tennyson’s contemporary world.

- Characterize “Ulysses” as a dramatic monologue.

Biography

Alfred Tennyson was born into a middle class family in Lincolnshire, the son of a clergyman. Tennyson attended Trinity College, Cambridge where he published his first collection of poetry written with his two older brothers, both already students at Cambridge. The volume was called Poems by Two Brothers although all three collaborated on the work. Also while at Cambridge Tennyson became close friends with Arthur Henry Hallam. While visiting Tennyson’s family, Hallam met and later became engaged to one of Tennyson’s sisters. Before the marriage could take place, Hallam died. Tennyson’s devastation over Hallam’s death led him to write one of his greatest poems, the elegy In Memoriam A.H.H. The following verses from In Memoriam record a visit made to Trinity College after Tennyson’s student days; he describes walking through the campus to visit Hallam’s old rooms:

LXXXVII

‘I past beside the reverend walls

In which of old I wore the gown;

I roved at random through the town,

And saw the tumult of the halls;

And heard once more in College fanes

The storm their high-built organs make,

And thunder-music, rolling, shake

The prophet blazoned on the panes;

And caught once more the distant shout,

The measured pulse of racing oars

Among the willows; paced the shores

And many a bridge, and all about

The same gray flats again, and felt

The same, but not the same; and last

Up that long walk of limes I past

To see the rooms in which he dwelt.’

After his father’s death, Tennyson left Cambridge before graduating to assist his family. His 1833 volume of poems, which included “The Lady of Shalott,” received poor reviews. Discouraged by the criticism, he didn’t publish another volume until 1842. That volume, including “Ulysses,” was extremely popular with the public and was quickly followed by his long poems The Princess and In Memoriam A.H.H. When the Poet Laureate William Wordsworth died in 1850, Tennyson’s popularity led to his being appointed to the post. In addition, Queen Victorian, who admired Tennyson’s poetry, offered him a title and estate.

Tennyson, now Lord Tennyson, moved to his Farringford estate on the Isle of Wight, off the southern coast of England.

Farringford, Lord Tennyson’s home on the Isle of Wight.

While living at Farringford, Tennyson, a favorite of Queen Victoria, visited her at her Isle of Wight home, Osborne House. Tennyson took long rambling walks over the downs of the Isle of Wight, an area now known as Tennyson Down.

Tennyson Monument on Tennyson Down, Isle of Wight.

Tennyson’s study at Farringford.

When Tennyson died at age 83, he was buried in Westminster Abbey’s Poets Corner, next to Robert Browning.

Texts

- “Crossing the Bar.” rpt. from English Poetry III: From Tennyson to Whitman. The Harvard Classics. 1909–14. Bartleby.com.

- “Crossing the Bar.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

- Idylls of the King. A Penn State Electronic Classics Series Publication. Jim Manis, Faculty Editor.

- Idylls of the King. The Project Gutenberg EBook of Idylls of the King, by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

- In Memoriam. Ed. W. J. Rolfe. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1895. University of Toronto, Robarts Library. Internet Archives.

- In Memoriam. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1865. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- “The Lady of Shalott.” The Camelot Project at The Rochester University. comparison of 1833 and 1842 versions.

- “The Lady of Shalott.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

- “Ulysses.” rpt. from Edmund Clarence Stedman, ed. A Victorian Anthology, 1837–1895. Bartleby.com.

- “Ulysses.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

In Memoriam

Published at mid-century, 1850, the poem’s publication date symbolizes its philosophy, half-way between the mysticism of Coleridge’s “Eolian Harp” and Hardy’s “strings of a broken lyre.” In contrast with the Romantic view of nature as a spiritual or intellectual force, In Memoriam’s first six sections picture nature as an indifferent force and then, in section 130, the speaker recognizes Hallam’s essence in nature.

Tracing the speaker’s journey through grief, from despair to doubt and eventually to a reaffirmation of faith, In Memoriam embodies the Victorian conflict of faith and doubt. Rather than a stabilizing, constant force, faith appears to crumble in the midst of personal and social disorder.

In the Prologue, the speaker affirms faith in God in the famous first stanza:

Strong Son of God, immortal Love,

Whom we, that have not seen thy face,

By faith , and faith alone, embrace,

Believing where we cannot prove.

In stanza 5 of the Prologue, the speaker acknowledges that “our little systems”—which may refer to organized religion, to social structures, to governments, to scientific theories, to any systems resulting from human endeavors to impose order and certainty on the world—eventually fail.

Our little systems have their day;

They have their day and cease to be:

They are but broken lights of thee,

And thou, O Lord, art more than they.

The structure and unity of the poem hinge on time, the three Christmas Eves described in the poem. Otherwise the progression of ideas seems to wander from despair to hope and faith and back to despondency, perhaps a realistic picture of a journey through personal grief.

In Memoriam consists of 131 sections plus a prologue and an epilogue, all of varying numbers of stanzas composed of 4 lines of iambic tetrameter rhyming ABBA.

“The Lady of Shalott”

In “The Lady of Shalott,” Tennyson draws on the Arthurian legends, the stories of King Arthur and his knights of the Round Table, which he also uses in his major work, Idylls of the King.

While writing about the mythical medieval world of Camelot, Tennyson poses questions about his Victorian world: were Victorians, especially the upper classes, becoming complacent and self-satisfied; what is the relationship of the artist and the world?

The Lady of Shalott lives shut away in a tower on an island near Camelot. Note the description of her island in stanzas 1 and 2. Words such as “lilies” (which usually are white), “willows whiten,” “aspens” (which have whitish bark), “gray walls,” “gray towers,” and “silent” all add up to a picture of a drab, colorless world inhabited by the Lady.

Part 2 informs us that the Lady of Shalott spends her life weaving in her tower. Because of a curse that has been put on her, she cannot even look out the window, certainly not go outside the tower into the world. She can see the world only through her weaver’s mirror which reflects the events going on outside her window. Tennyson does not give us any information about the “curse”; we don’t know who cursed the Lady or why. Apparently Tennyson considers these details unimportant; we accept the curse as a supernatural, fairy tale element. The focus, instead, is on the Lady’s reaction to her banishment from being involved in the world. Notice the last two lines of Part 2.

In Part 3, attention shifts to the world outside the tower as Sir Lancelot rides by. In contrast to the pale, colorless description of the Lady’s world, Sir Lancelot is described in bright, colorful terms: “dazzling,” “flamed,” “sparkled,” “glittered,” “golden,” “blazoned,” “jeweled,” “glowed,” “burnished,” “flashed.” The last stanza of Part 3 relates the Lady’s reaction to seeing Sir Lancelot in her mirror.

Part 4 concludes the story. As soon as the Lady looks out the window and directly at the world, the curse comes upon her. Her weaving, her art, flies out the window. She leaves her tower, climbs into a boat, and dies as the boat drifts toward Camelot. Ironically, Sir Lancelot voices a final blessing on the Lady of Shalott.

Many artists have painted their impressions of Tennyson’s poem. One of the most well-known is this painting by John William Waterhouse.

The Lady of Shalott, based on Tennyson’s poem.

Source: John William Waterhouse 1888.

Idylls of the King

At Farringford Tennyson finished one of his major works, the long poem Idylls of the King, a series of twelve narrative poems based on the Arthurian legends.

The first four Idylls, published in 1856, were “Enid,” “Vivien,” “Elaine,” and “Guinevere.” As suggested by the title Tennyson originally planned, The True and the False, these four idylls place four women characters on a spectrum of good and evil, fidelity and betrayal, idealism and reality. The rejection of The True and the False as a title in favor of The Idylls of the King shifts the focus to Arthur. Rather than standing individually, the four women in the completed work serve as pivotal points in a schema dominated by the king. Although revised and fitted into this more expansive plan, the four poems are still the cornerstones of The Idylls, their stories functioning as vehicles for the presentation of theme. The complexity of theme is reflected in the complexity of the characters’ dilemmas, and is played out, not among the four women or in an attempt to place them on a spectrum, but in each individual’s effort to deal with the real and the ideal. In each idyll, Arthur’s standards, his values, his vision are the controls which govern the action and the result.

In 1862, Tennyson dedicated the expanded work to the memory of Prince Albert, much to the pleasure of the widowed Queen Victoria. In the epilogue “To the Queen,” Tennyson describes his work as “shadowing Sense at war with Soul,” an expression of the faith and doubt conflict of the Victorian Age. In this war of Sense and Soul, Arthur’s stance is the touchstone and Enid, Vivien, Elaine, and Guinevere, the tokens of the battle.

The Idylls of the King may be read as Tennyson’s commentary on problems he recognized in Victorian society, including loss of religious faith, the dehumanizing effects of industrialization, complacency among the upper classes, and the active versus the inactive life.

“Ulysses”

For the dramatic monologue, “Ulysses,” Tennyson borrows a character from classical Greek literature, the Odyssey. Tennyson portrays the main character Ulysses (the Latin version of the Greek name Odysseus) after he has returned home from his 20-year voyage following the Trojan War.

Because this poem is a dramatic monologue, we can identify the four characteristics of that form. The fictional speaker of the poem is, of course, Ulysses. The dramatic moment is a moment of choice in his life: he has to decide whether to stay at home to rule his kingdom or to return to the sea for more adventures (see line 6). The silent but identifiable listeners are his mariners, the sailors whom he tries to convince to accompany him on one more great voyage (see lines 45–46). The entire poem provides a vivid picture of Ulysses as a man not content to sit at home but who wants to cram as much experience as possible into his life.

In the first stanza, Ulysses speaks disparagingly of his people, referring to them in animal terms (lines 4–5). He complains about the idleness of his life and how old his wife has become (apparently not realizing that she is also stuck with an old husband).

Stanza 2 proclaims Ulysses’s desire to live life to the fullest. In the well-known lines 22–26 he complains about the dullness of retiring from an active life and expresses his wish to live as fully as possible in the time remaining.

In stanza 3, Ulysses turns to his son Telemachus, expressing his intent to leave him in charge of ruling Ithaca. A question raised in these lines is if Ulysses thinks less of his son for staying at home instead of seeking new experiences like his father. Consider lines 39–40.

In stanza 4, Ulysses addresses his mariners, urging them to accompany him. He concedes that they are old, yet convinces them that even in old age “some work of noble note” may still be accomplished. See lines 49–57. The last line of the poem is a famous one that expresses Ulysses’s determination to keep trying, to keep accomplishing, rather than to be satisfied with past accomplishments.

Both of these poems, “The Lady of Shalott” and “Ulysses,” employ a common theme in Tennyson’s work: the active life versus the inactive life. Both poems portray characters who make a decision to become actively involved in life when they might more safely sit on the sidelines. Tennyson includes in these works a message for his Victorian society; he fears that they, too, may become complacent. In a century pleased with its expansive empire, its technological and industrial progress, and its scientific advances, Tennyson reminds readers that there are always new horizons to explore.

“Crossing the Bar”

Tennyson stated that he composed “Crossing the Bar” while sailing from the Isle of Wight to the mainland at Lymington. Composed in 1889, the poem is often considered an elegy for Tennyson himself. Before his death in 1892, Tennyson requested that “Crossing the Bar” be placed last in every collection of his poetry.

View from a ferry crossing the Isle of Wight to Lymington.

Crossing the Bar

Sunset and evening star,

And one clear call for me!

And may there be no moaning of the bar,

When I put out to sea,

But such a tide as moving seems asleep,

Too full for sound and foam,

When that which drew from out the boundless deep

Turns again home.

Twilight and evening bell,

And after that the dark!

And may there be no sadness of farewell,

When I embark;

For though from out our bourne of Time and Place

The flood may bear me far,

I hope to see my Pilot face to face

When I have crossed the bar.

Key Takeaways

- Tennyson’s In Memoriam may be read as a personal working through grief and as an expression of Victorian conflict leading toward a modern view of nature and social order.

- Tennyson’s Arthurian works also reflect conflicts evident in Victorian thought.

Exercises

-

Compare Tennyson’s lines from In Memorian with Shelley’s lines from another of the great elegies, Adonais:

Our little systems have their day;

They have their day and cease to be:

They are but broken lights of thee,

And thou, O Lord, art more than they.

Tennyson

The One remains, the many change and pass;

Heaven’s light forever shines, Earth’s shadows fly;

Life, like a dome of many-coloured glass,

Stains the white radiance of Eternity,

Until Death tramples it to fragments.

Shelley

- Although published before On the Origin of Species (1859), the quotation “Nature red in tooth and claw” (In Memoriam, section 56) is often cited as characterizing Darwin’s idea of natural selection. Trace references to nature throughout the poem and identify those that suggest a naturalist view, (literature that posits an indifferent natural universe working according to scientific law and that sees human action as the result of natural processes and the environment) and those that suggest a more Romantic view.

- Critics have interpreted the Lady of Shalott as depicting the dilemma of artists with a choice of living in the world or alienating themselves from the world to devote themselves to their art. Evaluate “The Lady of Shalott” as a statement of an artist’s relationship to society.

- Why did the Lady of Shalott look out her window even though she knew a curse would come upon her?

- In your opinion, did the Lady of Shalott do the right thing in looking out the window?

- What is your opinion of Ulysses? Do you admire his desire to keep striving to achieve more in his life, or do you think he was abandoning his responsibilities to his kingdom?

-

“Ulysses” is a dramatic monologue. Analyze the poem as a dramatic monologue by identifying the four characteristics of dramatic monologues:

- a fictional speaker

- a speech made at a dramatic moment in the speaker’s life

- a silent but identifiable listener

- a revelation of the speaker’s character

- What is the overriding metaphor of “Crossing the Bar”? Identify the various specifics of the nautical metaphor.

Resources

General Information

- “Alfred Tennyson.” Dr. John P. Farrell, University of Texas. Studies of Victorian Literature. images, texts, and critiques.

- Alfred Tennyson. The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

Biography

- “Alfred, Lord Tennyson.” Cambridge Authors. Cambridge University.

- “Alfred Lord Tennyson: A Brief Biography.” The Victorian Web. Prof. Glenn Everett, University of Tennessee at Martin.

- “Alfred Lord Tennyson Chronology.” The Victorian Web. Prof. Glenn Everett, University of Tennessee at Martin.

- “Lord Alfred Tennyson.” Academy of American Poets. Poets.org.

Texts

- “Crossing the Bar.” rpt. from English Poetry III: From Tennyson to Whitman. The Harvard Classics. 1909–14. Bartleby.com.

- “Crossing the Bar.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

- Idylls of the King. A Penn State Electronic Classics Series Publication. Jim Manis, Faculty Editor.

- Idylls of the King. The Project Gutenberg EBook of Idylls of the King, by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

- In Memoriam. Ed. W. J. Rolfe. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1895. University of Toronto, Robarts Library. Internet Archives.

- In Memoriam. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1865. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- “The Lady of Shalott.” The Camelot Project at The Rochester University. comparison of 1833 and 1842 versions.

- “The Lady of Shalott.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

- “Ulysses.” rpt. from Edmund Clarence Stedman, ed. A Victorian Anthology, 1837–1895. Bartleby.com.

- “Ulysses.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

Audio

- “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” Wax cylinder recording of Tennyson reading part of his poem.

- “Crossing the Bar.” LibriVox.

- “The Lady of Shalott.” LibriVox.

- “Reading Tennyson: 23 October 2009.” A Celebration of the Bicentenary of the Birth of Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Faculty of English. Cambridge University.

- “Ulysses.” LibriVox.

Images

- “Pictorial Interpretations of Tennyson’s ‘The Lady of Shalott.’” The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

Video

- “Alfred Tennyson—Proms Literary Festival.” BBC Radio 3 Video. YouTube.

Podcast

- “Tennyson’s In Memoriam.” In Our Time. BBC Radio 4.