This is “Robert Browning (1812–1889)”, section 7.5 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

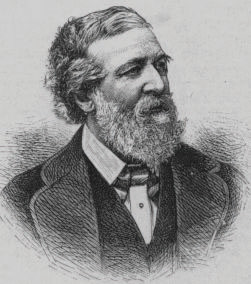

7.5 Robert Browning (1812–1889)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Define dramatic monologue and apply the definition to appropriate poems by Robert Browning.

- Define lyric and apply the definition to appropriate poems by Robert Browning.

- Describe the speakers in “Porphyria’s Lover,” “My Last Duchess,” and “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed’s Church.” Consider their words, implied actions, tone, and inferences drawn from their speeches.

Biography

Robert Browning was born in 1812, the son of a prosperous bank clerk and a nonconformist, musical mother. His father collected a voluminous library, and, disliking school, Browning grew up largely self educated in his father’s library, both he and his sister Sarianna immersed in a household filled with music, art, and literature. His early poems, such as Pauline and Paracelsus, attracted little attention. Encouraged by an actor friend, William Macready, Browning attempted to write several plays, none of which was particularly successful on stage. His next published long poem Sordello was ravaged by critics and popular writers of the time, such as Tennyson and Thomas Carlyle, and earned Browning a reputation for “obscurity” which persists to the present.

Browning’s attempts at writing plays did lead him to develop a form for which he is most well-known, the dramatic monologue, a poem spoken by a single speaker to a recognizable but silent audience at a critical moment in the speaker’s life. Although he did not invent the dramatic monologue form, he perfected it and used it so well that it has come to be closely associated with Browning.

The negative critical reception much of Browning’s early work received may account for the exceptional notice he took of Elizabeth Barrett’s mention of him in her poem “Lady Geraldine’s Courtship”:

Or from Browning some “Pomegranate,” which, if cut deep down the middle, shows a heart within blood-tinctured of a veined humanity.

Feeling as if he’d found someone who understood his poetry, Browning began corresponding with Barrett and, through mutual friend John Kenyon, one of London’s literati, arranged to meet her. After their marriage and move to Florence, Italy, the most productive period of Browning’s life began with the publication of Men and Women in 1855.

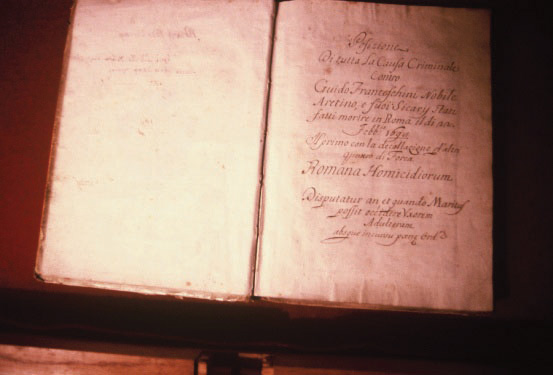

Browning’s magnum opus The Ring and the Book is a verse novel consisting of twelve books, ten books presenting ten dramatic monologues recounting a sensational murder trial that took place in Italy in 1698. In the introductory Book I, Browning describes walking through a street market in Florence and purchasing what he called The Old Yellow Book, a compilation of documents pertaining to the trial from which he drew the story conveyed in The Ring and the Book. This is the “Book” of the title. The “Ring” of the title may refer to an actual ring or to the ring of stories which attempt to arrive at the truth of the murder case. The verse novel is an experiment in dialectical writing, a story told through nine different filters (one character, the murderer Guido Franceschini, speaks two books), nine characters with their own preconceptions and circumstances which color their versions of the truth. The speakers of the monologues reveal as much about themselves as they do about the murder—which is the main purpose of a dramatic monologue: to reveal the character of the speaker.

The Old Yellow Book on display in the Browning Room at Balliol College, Oxford.

By the time of his death in 1889, Browning had become a major figure in England’s literary scene. He was buried in Westminster Abbey’s Poets Corner although he had expressed to his son his desire to be buried next to his wife Elizabeth Barrett Browning in Florence, Italy.

Texts

- “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed’s Church Rome, 15—.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed’s Church, 15—.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

- “Home Thoughts from Abroad.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “My Last Duchess.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “My Last Duchess.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

- “Porphyria’s Lover.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “Porphyria’s Lover.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

- “Prospice.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

The Dramatic Monologue

From John Donne in the 17th century to Robert Burns in the late 18th century, poets wrote dramatic monologues. Browning, however, is most often associated with the form, and his dramatic monologues are considered his best poems.

Although the dramas that Browning wrote early in his career were not successful as theater productions, they reveal a gift for creating fictional characters and presenting them through their speeches. While this made “talky,” uninteresting stage presentations, it created dynamic poetry.

A dramatic monologue has the following four characteristics:

- a fictional speaker

- a speech made at a dramatic moment in the speaker’s life

- a silent but identifiable listener

- a revelation of the speaker’s character

Think of a dramatic monologue as a scene in a play, but a scene in which only one of the characters on stage speaks. The “I” of a dramatic monologue is not the poet; the poet makes up a character who delivers the speech. It is this fictional character whose life and thoughts we hear about.

The speech that is the dramatic monologue is given at a dramatic moment in the speaker’s life; some significant event has or is about to occur.

The existence of a silent but identifiable listener means that the speaker is not the only character present in this scene. We can tell from the speaker’s comments that another person (or persons) is present, but the poem contains only the words of the speaker.

A dramatic monologue reveals the character of the speaker. By hearing what s/he says, we know what kind of person s/he is.

Robert Browning was interested in psychology; his dramatic monologues give us insight into a variety of people—some good, some evil. In “Porphyria’s Lover,” for example, Browning takes his audience into the mind of a psychotic man. We wonder how someone could commit such a violent act, and Browning’s poem attempts to let us see how this criminally insane mind works.

Porphyria’s Lover

The rain set early in tonight,

The sullen wind was soon awake,

It tore the elm-tops down for spite,

And did its worst to vex the lake:

I listened with heart fit to break.

When glided in Porphyria; straight

She shut the cold out and the storm,

And kneeled and made the cheerless grate

Blaze up, and all the cottage warm;

Which done, she rose, and from her form

Withdrew the dripping cloak and shawl,

And laid her soiled gloves by, untied

Her hat and let the damp hair fall,

And, last, she sat down by my side

And called me. When no voice replied,

She put my arm about her waist,

And made her smooth white shoulder bare,

And all her yellow hair displaced,

And, stooping, made my cheek lie there,

And spread, o’er all, her yellow hair,

Murmuring how she loved me—she

Too weak, for all her heart’s endeavor,

To set its struggling passion free

From pride, and vainer ties dissever,

And give herself to me forever.

But passion sometimes would prevail,

Nor could tonight’s gay feast restrain

A sudden thought of one so pale

For love of her, and all in vain:

So, she was come through wind and rain.

Be sure I looked up at her eyes

Happy and proud; at last l knew

Porphyria worshiped me: surprise

Made my heart swell, and still it grew

While I debated what to do.

That moment she was mine, mine, fair,

Perfectly pure and good: I found

A thing to do, and all her hair

In one long yellow string l wound

Three times her little throat around,

And strangled her. No pain felt she;

I am quite sure she felt no pain.

As a shut bud that holds a bee,

I warily oped her lids: again

Laughed the blue eyes without a stain.

And l untightened next the tress

About her neck; her cheek once more

Blushed bright beneath my burning kiss:

I propped her head up as before,

Only, this time my shoulder bore

Her head, which droops upon it still:

The smiling rosy little head,

So glad it has its utmost will,

That all it scorned at once is fled,

And I, its love, am gained instead!

Porphyria’s love: she guessed not how

Her darling one wish would be heard.

And thus we sit together now,

And all night long we have not stirred,

And yet God has not said a word!

“My Last Duchess” is based on an historical incident involving the Duke of Ferrara, Italy during the Renaissance.

My Last Duchess

Ferrara

That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall,

Looking as if she were alive. I call

That piece a wonder, now: Frà Pandolf’s hands

Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

Will’t please you sit and look at her? I said

“Frà Pandolf” by design: for never read

Strangers like you that pictured countenance,

The depth and passion of its earnest glance,

But to myself they turned (since none puts by

The curtain I have drawn for you, but I)

And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst,

How such a glance came there; so, not the first

Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, ‘twas not

Her husband’s presence only, called that spot

Of joy into the Duchess’ cheek: perhaps

Frà Pandolf chanced to say “Her mantle laps

Over my lady’s wrist too much,” or “Paint

Must never hope to reproduce the faint

Half-flush that dies along her throat:” such stuff

Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough

For calling up that spot of joy. She had

A heart—how shall I say?—too soon made glad,

Too easily impressed; she liked whate’er

She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

Sir, ‘twas all one! My favour at her breast,

The dropping of the daylight in the West,

The bough of cherries some officious fool

Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule

She rode with round the terrace—all and each

Would draw from her alike the approving speech,

Or blush, at least. She thanked men,—good! but thanked

Somehow—I know not how—as if she ranked

My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name

With anybody’s gift. Who’d stoop to blame

This sort of trifling? Even had you skill

In speech—(which I have not)—to make your will

Quite clear to such an one, and say, “Just this

Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss,

Or there exceed the mark”—and if she let

Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set

Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse,

—E’en then would be some stooping: and I choose

Never to stoop. Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt,

Whene’er I passed her; but who passed without

Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands;

Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands

As if alive. Will’t please you rise? We’ll meet

The company below, then. I repeat,

The Count your master’s known munificence

Is ample warrant that no just pretence

Of mine for dowry will be disallowed;

Though his fair daughter’s self, as I avowed

At starting, is my object. Nay, we’ll go

Together down, sir. Notice Neptune, though,

Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity,

Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me!

“The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed’s Church” also takes place in Renaissance Italy. The Bishop is on his deathbed and addresses “Nephews—sons mine…ah, God I know not!” In the next line he refers to his long-ago mistress. The implication of calling the priests gathered around his bed first nephews then sons followed immediately by a reference to his mistress is that he has fathered them but, as a priest, has pretended they are his nephews for so long that now, in the confusion of his mind as he faces death, he is not sure of the truth himself. The Bishop continues throughout his monologue to reveal that he is far from a devout clergyman.

His purpose in calling his sons/nephews to his deathbed is, as the title states, to order his tomb, to give them instructions for constructing his monument in the church. He compares himself and the tomb he wants to that of his rival in life, Gandalf. We learn that they were rivals for everything from position in the church to the mistress that bore his children.

The Bishop orders the finest, most expensive of materials and the most elaborate of ornamentation. The extent of the Bishop’s depravity is revealed in lines such as these when he describes the items he wants carved on his tomb:

The Saviour at his sermon on the mount,

Saint Praxed in a glory, and one Pan

Ready to twitch the Nymph’s last garment off,

And Moses with the tables

The sacrilegious combination of Christ, Moses, and a saint with the mythological Pan taking off a girl’s clothes represents the combination of sacred and profane that has been his life. Overall, the audience is struck foremost by the fact that in the Bishop’s last moments of life, his thoughts are not of his God and the state of his immortal soul but of material and worldly matters.

Lyric Poems

Although Browning is known primarily for his dramatic monologues, he also wrote lyric poetryA brief poem, expressing emotion, imagination, and meditative thought, usually stanzaic in form., brief poems expressing emotion, imagination, and meditative thought, usually stanzaic in form such as “Home Thoughts from Abroad” and “Prospice.”

In “Home Thoughts” the speaker longs nostalgically to be back in his home country of England. The reference to the “gaudy melon flower” represents Italy and contrasts with the delicate beauties of England in spring.

“Prospice,” written months after Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s death, expresses courage and faith in the face of death. The last lines are considered a statement of Browning’s personal belief that he will be reunited with his wife after death:

O thou soul of my soul! I shall clasp thee again,

And with God be the rest!

Home Thoughts from Abroad

Oh, to be in England

Now that April’s there,

And whoever wakes in England

Sees, some morning, unaware,

That the lowest boughs and the brushwood sheaf

Round the elm-tree bole are in tiny leaf,

While the chaffinch sings on the orchard bough

In England—now!

And after April, when May follows,

And the white-throat builds, and all the swallows!

Hark I where my blossomed pear tree in the hedge

Leans to the field and scatters on the clover

Blossoms and dewdrops—at the bent spray’s edge—

That’s the wise thrush; he sings each song twice over,

Lest you should think he never could recapture

The first fine careless rapture!

And though the fields look rough with hoary dew,

All will be gay when noontide wakes anew

The buttercups, the little children’s dower

—Far brighter than this gaudy melon-flower!

Prospice*

Fear death? to feel the fog in my throat,

The mist in my face,

When the snows begin, and the blasts denote

I am nearing the place,

The power of the night, the press of the storm,

The post of the foe;

Where he stands, the Arch Fear in a visible form,

Yet the strong man must go:

For the journey is done and the summit attained,

And the barriers fall,

Though a battle’s to fight ere the guerdon be gained,

The reward of it all.

I was ever a fighter, so—one fight more,

The best and the last!

I would hate that death bandaged my eyes, and forbore,

And bade me creep past,

No! let me taste the whole of it, fare like my peers

The heroes of old,

Bear the brunt, in a minute pay glad life’s arrears

Of pain, darkness, and cold.

For sudden the worst turns the best to the brave,

The black minute’s at end,

And the elements’ rage, the fiend-voices that rave,

Shall dwindle, shall blend,

Shall change, shall become first a peace out of pain,

Then a light, then thy breast,

O thou soul of my soul! I shall clasp thee again,

And with God be the rest!

*looking forward

Key Takeaways

- Known primarily for his dramatic monologues, Robert Browning also wrote lyric poetry, a verse novel, and plays.

- A dramatic monologue is a poem spoken by a single speaker to a recognizable but silent audience at a critical moment in the speaker’s life.

- Browning’s reading about history, art, and music allowed him to portray historical figures and artists realistically in his dramatic monologues.

Exercises

- Browning, like other Victorian writers, uses nature in his work, but without the sense of Romantic mysticism that pervades most Romantic era poetry. Describe the weather on the night Porphyria was murdered in “Porphyria’s Lover.” How does the description of the weather reinforce the atmosphere of the poem?

- What was the murder weapon in “Porphyria’s Lover”?

- Why did Porphyria’s lover choose that particular moment to murder her? Identify specific lines in the poem that explain his motivation.

- The silent but identifiable listener is not as easily identified in “Porphyria’s Lover.” Browning originally published this poem and one other (“Johannes Agricola in Meditation”) under the title “Madhouse Cells.” In the 19th century insane asylums were much more like prisons than hospitals. At the time there was little understanding of mental illnesses or how to treat them. Mentally disturbed people were frequently locked away in what was essentially a prison. To make the situation even worse, the public was allowed to pay an admission fee and to tour the insane asylum, looking into the various cells at the inmates in the same way we might look at animals in a zoo for entertainment. With the title “Madhouse Cells,” perhaps Browning had in mind that the speaker, Porphyria’s lover, was in a cell in such an insane asylum. With this knowledge in mind, who do you think might be the silent listener?

- In “My Last Duchess, what happened to the last duchess?

- What art work is the Duke revealing to his guest?

- What is the Duke currently negotiating for?

- In “The Bishop Orders His Tomb,” who is Anselm?

- Who is Gandalf?

- List evidence that indicates the Bishop is not a devout clergyman.

- Does the bishop assume that his wishes for his tomb will be carried out? Why?

-

Analyze the dramatic monologue form in “Porphyria’s Lover,” “My Last Duchess,” and “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed’s Church” by answering the following questions:

- Who is the speaker?

- What is the situation?

- Who is the silent listener?

- What do you find out about the speaker’s character?

Resources

General Information

- “About the Poems of Robert Browning.” Josephine Hart on Robert Browning. Learning: Poetry and Performance. The British Library.

- “Robert Browning.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George P. Landow, Brown University.

Biography

- “Biography of Robert Browning.” Learning: Poetry & Performance. The British Library.

- The Browning Letters. Baylor University and Wellesley College.

- “Robert Browning.” The Browning Society.

- “Robert Browning.” Studies of Victorian Literature. Dr. John P. Farrell, University of Texas, Austin.

- “Robert Browning (1812–1889).” The Brownings. Armstrong Browning Library. Baylor University.

- “Robert Browning—Biography.” The Victorian Web. Glenn Everett, University of Tennessee at Martin.

- “Robert Browning Chronology.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George P. Landow, Brown University.

Texts

- “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed’s Church Rome, 15—.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed’s Church, 15—.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

- “Home Thoughts from Abroad.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “My Last Duchess.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “My Last Duchess.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

- “Porphyria’s Lover.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “Porphyria’s Lover.” The Victorian Web. Dr. George Landow, Brown University.

- “Prospice.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lancashire, Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

Dramatic Monologue

- Browning’s “My Last Duchess” and Dramatic Monologue. National Endowment for the Humanities. Edsitement!

- “Poetic Technique: Dramatic Monologue.” The Academy of American Poets. Poets.org.

Audio

- “Home Thoughts from Abroad.” LibriVox.

- “How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix—an extract.” The Poetry Archive. recording of Robert Browning reciting a few lines of his poem recorded on an Edison cylinder in 1889, the year of Browning’s death.

- “My Last Duchess.” LibriVox.

- “Prospice.” LibriVox.

- “Robert Browning (1812–1889).” The Poetry Archive. recording of Browning reading lines from his “How They Brought the Good News.”

- “Robert Browning Read by Robert Hardy and Greg Wise.” Learning: Poetry & Performance. The British Library.

Video

- “About the Poems of Robert Browning.” Josephine Hart on Robert Browning. Learning: Poetry and Performance. The British Library.

- “Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning.” Dr. Carol Lowe. McLennan Community College.

- “Robert Browning Recites ‘How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix.’” Nick Wallace Smith, University of New South Wales. YouTube. recording of Robert Browning reciting a few lines of his poem recorded on an Edison cylinder in 1889, the year of Browning’s death.