This is “George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788–1924)”, section 6.10 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

6.10 George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788–1924)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

Learning Objectives

- Define and provide examples of the character type known as the Byronic hero.

- Appraise the characteristics of Romanticism apparent in Byron’s poetry, and compare and contrast their use in the poetry of Wordsworth and Coleridge.

- Recognize and interpret the theme of the aspiring spirit in Byron’s poetry.

Biography

“Mad, bad, and dangerous to know” is the infamous assessment of Lord Byron by Lady Caroline Lamb, herself a scandalous figure among the elite circles of early 19th-century aristocratic society.

Portrait of Byron at Newstead Abbey.

Byron inherited the rank of Baron after his father and his uncle died. Unfortunately, they had squandered the family fortune. Byron enjoyed noble rank but lacked the wealth necessary to maintain the lifestyle he believed should accompany it. He also inherited Newstead Abbey, the family estate, in disrepair, and could not afford to repair or even heat it.

Newstead Abbey, Byron’s ancestral home.

The ruins of the original abbey granted to Byron’s ancestors by Henry VIII.

Byron suffered from a malformed foot which caused him to limp badly, a source of embarrassment and indignity to him both in his childhood and as an adult. He formed close friendships with other young noblemen at Trinity College, Cambridge. While at Cambridge, Byron began to accumulate the gambling debts that would plague him all his life, eventually causing him to sell Newstead Abbey, the estate granted to his family six generations earlier by King Henry VIII. He also cultivated the reputation for perverted sexual promiscuity that characterized his public persona for the rest of his life, deserved according to some biographers, undeserved according to others. While at Cambridge, Byron published his first books of poetry.

Traditionally young men of Byron’s station undertook a Grand Tour of Europe after their graduation from college. Accompanied by a friend, Byron borrowed money to travel to Portugal, Albania, Turkey, Greece, and Italy. During this trip, Byron wrote the first two Cantos of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. Their publication brought him overnight fame, the kind of adulation that has been compared to that of a modern rock star.

Childe Harold was a character closely identified with Byron himself, the Byronic heroA dark, brooding figure, jaded and cynical, bored with and contemptuous of conventional society., a dark, brooding figure, jaded and cynical, bored with and contemptuous of conventional society. Byron continued to write long narrative poems featuring this type of character (The Giaour, The Bride of Abydos, The Corsair, Manfred) and at the same time continued to cultivate his own public anti-hero persona.

One of his most notorious escapades involved a love affair with the married Lady Caroline Lamb, a prominent member of the aristocracy who continued to pursue Byron publicly even after he tried to end the affair.

As an adult, Byron met and became close to his half-sister Augusta Leigh. Some biographers believe that he had an incestuous affair with her and that her daughter was Byron’s child.

Byron married Annabella Milbanke, a conventional young woman from a wealthy family. She lived with Byron until their daughter was born and then left him, unable to contend with his increasingly bizarre behavior. Some of Byron’s associates feared that he was insane when he fired his pistols in his house, abused his wife, and continued his scandalous sexual escapades. His wife left him, taking their daughter, obtained a divorce (virtually unheard of at that time), and returned to her family.

Memorial outside Byron’s burial place in Hucknall Church.

Realizing that the public was no longer fascinated but revolted by his behavior, Byron left England, never to return. Traveling first to Switzerland, Byron lived for a time near the poet Shelley and his then-companion, later wife Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin and her sister Claire Clairmont with whom Byron had another daughter. Moving to Italy, Byron had a long-standing affair with a married Italian noblewoman. During these travels he wrote Cantos 3 and 4 of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage and began what would be considered his greatest work, the satiric Don Juan.

Moving to Greece, Byron, even though he had no military expertise, became involved in the Greek fight for independence from the Ottoman Empire. While with the Greek forces, Byron contracted a fever and died. His body was returned to England but refused burial in Westminster Abbey because of his reputed immorality. He eventually was buried in a small church near his family’s former estate Newstead Abbey. Not until 1969 was a plaque honoring Byron placed in Westminster Abbey’s Poet’s Corner.

Texts

- Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Prisoner of Chillon.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lanchashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “She Walks in Beauty.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lanchashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “When We Two Parted.” Bartleby.com. rpt. from English Poetry II: From Collins to Fitzgerald. The Harvard Classics. 1909–14.

- Works of Byron. The International Byron Society.

- The Works of Lord Byron. Ed. Ernest Hartley Coleridge and R. E. Prothero. University of Virginia Library.

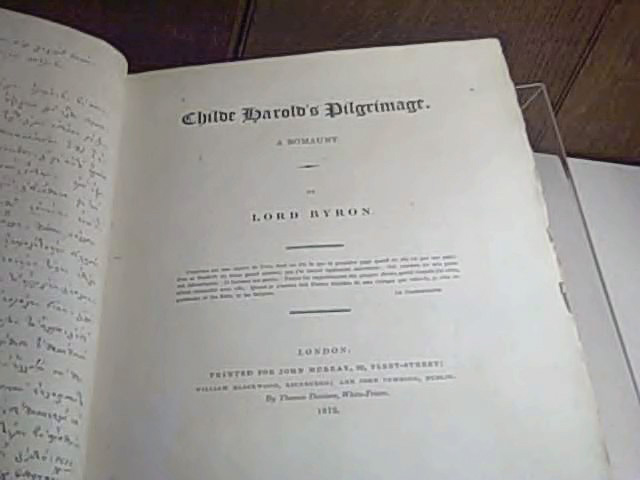

Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage

After the publication of the first two Cantos of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Byron declared that he awoke one morning to find himself famous.

First edition of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage in the library of Newstead Abbey.

The term childeA medieval expression referring to a young man in training to become a knight. is a medieval expression referring to a young man in training to become a knight. Canto 1 begins with a description of a young man, Childe Harold, in England (“Albion’s isle”) who is living a riotous, shameful life. He discovers he is satiated with his dissipated ways and sets out on a pilgrimage to discover some meaning in life.

The poem, and Childe Harold, reach a pivotal moment in the Canto 3 stanzas about Lake Leman in Switzerland. Although Byron writes about nature in this section, his poetry generally displays little of the preoccupation with nature seen in other Romantic writers.

His focus instead is man’s aspiring spirit. Nature is beautiful and peaceful compared with a world inhabited by humans driven by their aspiring spirits and indomitable wills.

Canto 3 from “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage”

Stanza 85

Clear, placid Leman! thy contrasted lake,

With the wild world I dwelt in, is a thing

Which warns me, with its stillness, to forsake

Earth’s troubled waters for a purer spring.

This quiet sail is as a noiseless wing

To waft me from distraction; once I loved

Torn Ocean’s roar, but thy soft murmuring

Sounds sweet as if a Sister’s voice reproved,

That I with stern delights should e’er have been so moved.

*****

Stanza 88

Ye Stars! which are the poetry of Heaven!

If in your bright leaves we would read the fate

Of men and empires,—’tis to be forgiven,

That in our aspirations to be great,

Our destinies o’erleap their mortal state,

And claim a kindred with you; for ye are

A Beauty and a Mystery, and create

In us such love and reverence from afar,

That Fortune,—Fame,—Power,—Life, have named themselves a Star.

Following a description of an overnight storm in which the speaker’s spirit soars and longs to express its “Soul, heart, mind, passions, feelings” (Stanza 97) as strongly and vividly as nature expresses itself in the storm, morning arrives with suggestions of the human spirit calm and refreshed after the storm of struggle.

Canto 3 from “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage”

Stanza 98

The Morn is up again, the dewy Morn,

With breath all incense, and with cheek all bloom—

Laughing the clouds away with playful scorn,

And living as if earth contained no tomb,—

And glowing into day: we may resume

The march of our existence: and thus I,

Still on thy shores, fair Leman! may find room

And food for meditation, nor pass by

Much, that may give us pause, if pondered fittingly.

Although line 8 of stanza 98 seems to echo Wordsworth’s claim that nature provides “life and food for future years,” Byron provides no hints of Wordsworth’s view of nature as divine revelation or a veil discreetly disclosing a spiritual presence. Nonetheless, nature is a source of wisdom and meditation.

“She Walks in Beauty Like the Night” and “When We Two Parted”

She Walks in Beauty

She walks in beauty—like the night

Of cloudless climes and starry skies,

And all that’s best of dark and bright

Meet in her aspect and her eyes;

Thus mellowed to the tender light

Which heaven to gaudy day denies.

One shade the more, one ray the less,

Had half impaired the nameless grace

Which waves in every raven tress

Or softly lightens o’er her face—

Where thoughts serenely sweet express

How pure, how dear their dwelling place.

And on that cheek and o’er that brow

So soft, so calm yet eloquent,

The smiles that win, the tints that glow

But tell of days in goodness spent

A mind at peace with all below,

A heart whose love is innocent.

This simple, eloquent lyric is said to have been written when Byron met a cousin who was wearing a black mourning dress covered in spangles. The speaker describes the woman in tender phrases which combine images of darkness and light.

When We Two Parted

When we two parted

In silence and tears,

Half broken-hearted

To sever for years,

Pale grew thy cheek and cold,

Colder thy kiss;

Truly that hour foretold

Sorrow to this.

The dew of the morning

Sunk chill on my brow—

It felt like the warning

Of what I feel now.

Thy vows are all broken,

And light is thy fame:

I hear thy name spoken,

And share in its shame.

They name thee before me,

A knell to mine ear;

A shudder comes o’er me—

Why wert thou so dear?

They know not I knew thee,

Who knew thee too well:

Long, long shall I rue thee,

Too deeply to tell.

In secret we met—

In silence I grieve,

That thy heart could forget,

Thy spirit deceive.

If I should meet thee

After long years,

How should I greet thee?

With silence and tears.

Like “She Walks in Beauty,” this lyric expresses deep emotion in simple and eloquent terms.

“The Prisoner of Chillon”

While staying with Shelley in Switzerland, Byron toured the Castle of Chillon on Lake Geneva (Lake Leman), including the dungeon he describes in this narrative poem. Byron’s name can still be seen carved on one of the pillars in the dungeon.

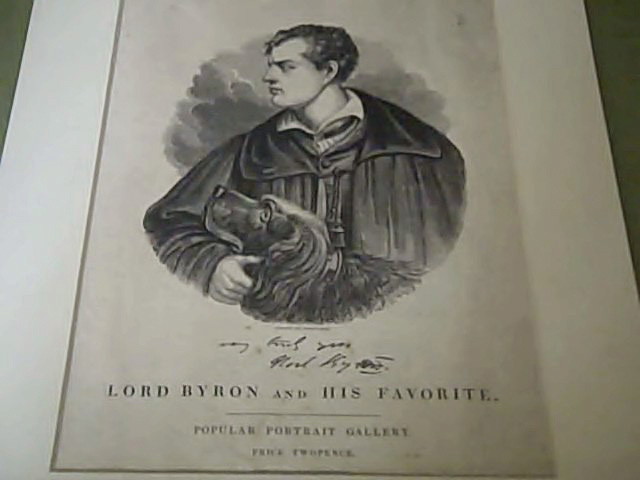

Portrait of Byron and his favorite dog in the library of Newstead Abbey.

One of the characteristics of Romanticism is an interest in the medieval past, and Byron loosely bases his story on the life of Francois Bonivard from the early 16th century. He imbues his story with one of his recurrent themes—the indomitable will of the human spirit.

Key Takeaways

- George Gordon, Lord Byron created the Byronic hero, a dark, brooding figure, jaded and cynical, bored with and contemptuous of conventional society

- Although in a different context than the poetry of Wordsworth and Coleridge, nature plays a significant role in Byron’s poetry.

- Other characteristics of Romanticism are apparent in Byron’s poetry.

- The aspiring spirit is a key theme in Byron’s poetry.

Exercises

-

Stanzas 85 through 98 in Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage are considered a climactic point in the poem. After reading these stanzas answer the following questions:

- What might Lake Leman represent in the speaker’s life?

- How does the speaker compare the natural world and the world inhabited by people?

- What do the stars represent in stanza 88?

- In stanza 90, what does the speaker mean when he says we are “least alone” in solitude?

- What does the storm symbolize? Refer to specific descriptions.

- How would you compare the use of nature in these stanzas with the use of nature in other Romantic poetry you have read?

- How would you compare the ideas in the last two lines of stanza 98 with ideas from Wordsworth’s “Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey” and Coleridge’s “This Lime-tree Bower My Prison”?

- In “She Walks in Beauty” how does the speaker equate physical beauty with beauty of character?

- What has happened in “When We Two Parted”?

- In the last stanza of “When We Two Parted” it’s clear that the speaker still remembers his lost love, but does the woman remember him? How do we know? Describe the speaker’s reaction when the two meet years later.

- Describe the narrator of “The Prisoner of Chillon.”

- What happens in stanza 10 of “The Prisoner of Chillon” and how does it change the narrator?

- How would you compare the use of nature in “The Prisoner of Chillon” with nature in the work of other Romantic writers?

- Describe the narrator’s reaction to being liberated at the end of the story.

Resources

General Information

- “Romantic Anger and Byron’s Curse.” Andrew M. Stauffer, University of Virginia. Praxis Series. Ed. Orrin N.C. Wang. Romantic Circles. General Editors, Neil Fraistat and Steven E. Jones. Technical Editor, Laura Mandell. University of Maryland.

Biography

- “The Byron Chronology.” Ann R. Hawkins, Texas Tech University. Romantic Circles. General Editors, Neil Fraistat and Steven E. Jones. Technical Editor, Laura Mandell. University of Maryland.

- “A Life of Byron.” The International Byron Society.

- Lord Byron 1788–1824. Keats-Shelley House.

- “Lord Byron (1788–1824).” BBC History. BBC.

- Lord Byron (George Gordon) 1788–1824. Poetry Foundation.Lord Byron (George Gordon)

- Lord Byron (George Gordon).

- “Notices of the Life of Lord Byron by Thomas Moore, 1835.” from Moores’ The Works of Lord Byron: With His Letters and Journals, and His Life. London. John Murray. 1835. The Life and Work of Lord Byron 1788–1824.

- “Statue of Byron.” Trinity College Cambridge.

Texts

- Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. Project Gutenberg.

- “The Prisoner of Chillon.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lanchashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “She Walks in Beauty.” Representative Poetry Online. Ian Lanchashire. Department of English, University of Toronto. University of Toronto Libraries.

- “When We Two Parted.” Bartleby.com. rpt. from English Poetry II: From Collins to Fitzgerald. The Harvard Classics. 1909–14.

- Works of Byron. The International Byron Society.

- The Works of Lord Byron. Ed. Ernest Hartley Coleridge and R. E. Prothero. University of Virginia Library.

Video

- “George Gordon, Lord Byron.” Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.

Audio

- “Child Harold’s Pilgrimage, Canto 4, Stanzas 178–186; ‘Stanzas,’ ‘So We’ll Go No More A Roving.” Tilar Mazzeo, ed. Poets On Poets. Romantic Circles. General Editors, Neil Fraistat and Steven E. Jones. Technical Editor, Laura Mandell. University of Maryland.

- “She Walks in Beauty.” LibriVox.

- “When We Two Parted.” LibriVox.

- “When We Two Parted.” Project Gutenberg.

Images

- Byronic Images: Portraits of the Poet, His Family & Friends.

- “George Gordon Byron.” Great Britons: Treasures from the National Portrait Gallery, London.