This is “Jane Austen (1775–1817)”, section 6.9 from the book British Literature Through History (v. 0.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

6.9 Jane Austen (1775–1817)

PLEASE NOTE: This book is currently in draft form; material is not final.

In her novels, Jane Austen fashions the quintessential picture of Regency England, the period from 1811–1820 in which Prince George served as Prince Regent to his father King George III. Bouts of insanity, now believed to have been caused by an illness and made worse by physicians and virtual imprisonment, made George III incapable of ruling, leading to the regency of his son and heir apparent, George, later to become King George IV on his father’s death. This era, dominated by the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, and the Industrial Revolution, juxtaposed world-changing political events and technological innovations with the ostentatious, consciously fashionable world of the Prince Regent and the aristocracy bound by strict rules of social behavior. The aristocracy viewed manners, living according to society’s strictures, as indicative of belonging to the coterie in a time when being ostracized by society was considered a fate worse than death. The title of Jane Austen’s first published novel, Sense and Sensibility, suggests an age influenced by 18th-century rationalism and 19th-century Romanticism.

Biography

Jane Austen spent her childhood in the village of Steventon, where her father was the rector and her family active in village social life. The seventh of eight children, Jane was particularly close to her only sister Cassandra throughout her life. Although she began writing in childhood, her first novel was not published until 1811. Austen apparently fell in love with a young man, Tom LeFroy, who visited the neighborhood for a time, but whose family sent for him to return home to Ireland when they became aware of his interest in Austen, the daughter of a poor, low-ranking clergyman. Her sister Cassandra was engaged to a man who died while on business in the Caribbean, and neither sister ever married.

Jane Austen’s home in Chawton.

After her father’s retirement, Austen moved with her family to Bath, a setting used in her novels. When her father died, the Austen sisters and their mother were financially dependent on Austen’s brothers. They lived for a time in Southampton with her brother Frank, a naval officer, and his wife and spent a good bit of their time traveling from relative to relative, a situation not uncommon for widows and spinsters in the early 19th century. Finally another brother, Edward, offered his mother and sisters the use of a house on his estate in Chawton. While living here Austen published four novels:

- Sense and Sensibility 1811

- Pride and Prejudice 1813

- Mansfield Park 1814

- Emma 1816

Two novels were published posthumously:

- Northanger Abbey 1818

- Persuasion 1818

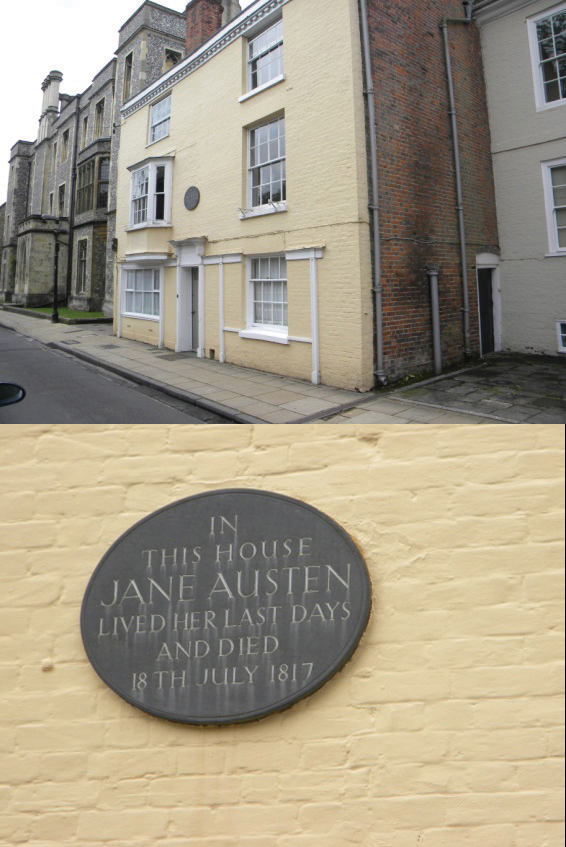

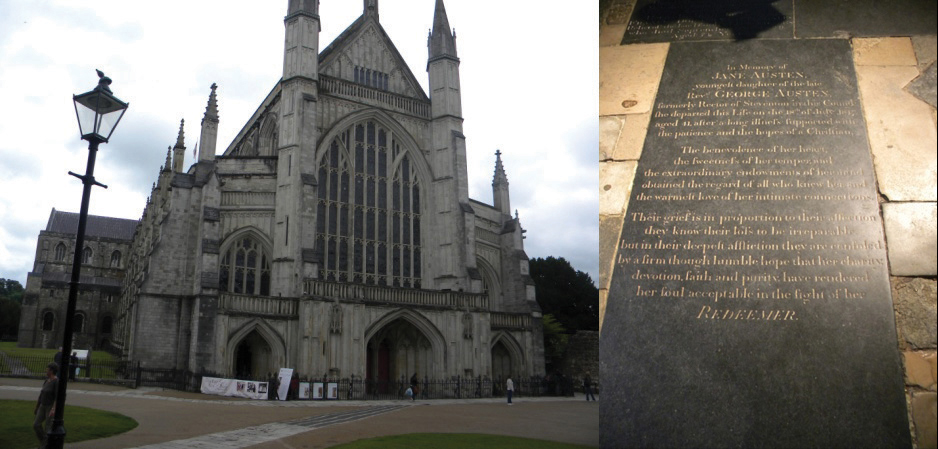

When Austen’s health began to fail, Cassandra moved with her to nearby Winchester, a larger city where medical help would be available. Austen died soon after the move and was buried in Winchester Cathedral.

Texts

- The Complete Project Gutenberg Works of Jane Austen. Project Gutenberg.

- Emma. Project Gutenberg.

- Mansfield Park. Project Gutenberg.

- Northanger Abbey. Project Gutenberg.

- Penn State’s Electronic Classics Series Jane Austen Page.

- Persuasion. Project Gutenberg.

- Pride and Prejudice. Project Gutenberg.

- Sense and Sensibility. Project Gutenberg.

Pride and Prejudice

Jane Austen’s works are novels of mannersNovels that portray and assess the values, customs, and behavior of a particular social stratum at a specific time in history., novels that portray and assess the values, customs, and behavior of a particular social stratum at a specific time in history. Indeed, one of the typical criticisms of Austen’s work is that her focus is an especially small segment of Regency society, the lower rung of landed gentry to which her own family belonged.

The Title

An early version of Pride and Prejudice was titled First Impressions, referring to the first impressions Elizabeth Bennett and Fitzwilliam Darcy have of each other. Although the same concept applies in the published title, the first impressions are named and set the tone for the novel.

The Characters

Although the Bennets, on the surface, seem ruled by the mores of their society, the story proves that most of the family ill fit the expectations society would have for them. Mr. Bennet cares too little for society and too much for scholarly pursuits, preferring to simply withdraw from the societal pressures that are his wife’s obsession. Although he is an immensely likable character, he lacks the leadership that might have averted some the family’s difficulties. Mrs. Bennet, on the other hand, is so concerned with appearances and making what society would deem appropriate arrangements for her daughters’ futures that she becomes almost a caricature of a society mother. Yet she apparently is much more aware of the reality of the family’s financial situation than Mr. Bennet.

Lady Catherine de Bourgh shares Mrs. Bennet’s esteem for society’s rules, but their characters are quite different, Lady Catherine a stereotype of the society matron and Mrs. Bennet of the foolish, pushy woman unable to see her own inappropriate behavior. Elizabeth and Lydia, too, could be seen as similar in their disregard for society’s conventions and yet with opposite results. Even Wickham cannot be seen as a totally evil character as his childhood circumstances may give him a sympathetic slant, especially to modern readers.

Key Takeaways

- Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice is a novel of manners focused on the life of lower ranking gentry in a small English village.

- Pride and Prejudice portrays characters caught between the expectations of their society and their personal desires.

- Some characters in Pride and Prejudice appear to deal with realistic dilemmas while others seems to be stereotypes of Regency society; none, however, are one dimensional as all characters realistically possess virtues and flaws.

Exercises

- How would the women of the Bennet family fit into Mary Wollstonecraft’s description of women in the late 18th, early 19th centuries?

- What expectations of society color the initial relationship between Elizabeth and Darcy? Do these expectations become more or less important as their relationship progresses? Explain how the title applies to their relationship at the beginning and throughout the novel.

- Compare and contrast the match of Jane and Bingley and that of Elizabeth and Darcy. Is one match more appropriate than the other? Why or why not?

- Elizabeth and Lydia both, in different ways, flaunt the expectations of society in their behavior and make marriages that society would deem inappropriate, yet readers (and most of the other characters) thoroughly approve of one and disapprove of the other. Why?

- How would you describe Elizabeth’s reaction to and feelings about Charlotte’s marriage to Mr. Collins?

- Analyze each of the major characters in the novel, making a list of assets and flaws.

- How accurate would you consider Austen’s portrayal of this segment of society?

- What circumstances in Jane Austen’s life might be seen as parallel with life in the novel?

Resources

General Information and Biography

- Biography: Life (1775–1817) and Family. A Celebration of Women Writers. Mary Mark Ockerbloom, Editor.

- Jane Austen. Harold Child. rpt. from The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21). Volume XII. The Romantic Revival. Bartleby.com.

- Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts. University of Oxford and King’s College London. digital images of Austen’s manuscripts

- Jane Austen’s House Museum.

Texts

- The Complete Project Gutenberg Works of Jane Austen. Project Gutenberg.

- Emma. Project Gutenberg.

- Lady Susan. Project Gutenberg.

- Mansfield Park. Project Gutenberg.

- Northanger Abbey. Project Gutenberg.

- Penn State’s Electronic Classics Series Jane Austen Page.

- Persuasion. Project Gutenberg.

- Pride and Prejudice. Project Gutenberg.

- Sense and Sensibility. Project Gutenberg.

Images

- Jane Austen’s Bath. Literary Landscapes. British Library.

- Jane Austen’s Early Works. Virtual Books. British Library.

Audio

- Emma. Project Gutenberg.

- Lady Susan. Project Gutenberg.

- Mansfield Park. Project Gutenberg.

- Northanger Abbey. Project Gutenberg.

- Persuasion. Project Gutenberg.

- Pride and Prejudice. Project Gutenberg.

- Sense and Sensibility. Project Gutenberg.

Video

- Jane Austen. Dr. Carol Lowe, McLennan Community College.