This is “The Payback Method”, section 8.5 from the book Accounting for Managers (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

8.5 The Payback Method

Learning Objective

- Evaluate investments using the payback method.

Question: Although the net present value (NPV) and internal rate of return (IRR) methods are the most commonly used approaches to evaluating investments, some managers also use the payback method. What is the payback method, and how does it help managers make decisions related to long-term investments?

Answer: The payback methodEvaluates how long it will take to recover the initial investment. evaluates how long it will take to “pay back” or recover the initial investment. The payback periodThe time it takes to generate enough cash receipts from an investment to cover the cash outflows for the investment., typically stated in years, is the time it takes to generate enough cash receipts from an investment to cover the cash outflows for the investment.

Managers who are concerned about cash flow want to know how long it will take to recover the initial investment. The payback method provides this information. Managers may also require a payback period equal to or less than some specified time period. For example, Julie Jackson, the owner of Jackson’s Quality Copies, may require a payback period of no more than five years, regardless of the NPV or IRR.

Note that the payback method has two significant weaknesses. First, it does not consider the time value of money. Second, it only considers the cash inflows until the investment cash outflows are recovered; cash inflows after the payback period are not part of the analysis. Both of these weaknesses require that managers use care when applying the payback method.

Payback Method Example

Question: What is the payback period for the proposed purchase of a copy machine at Jackson’s Quality Copies?

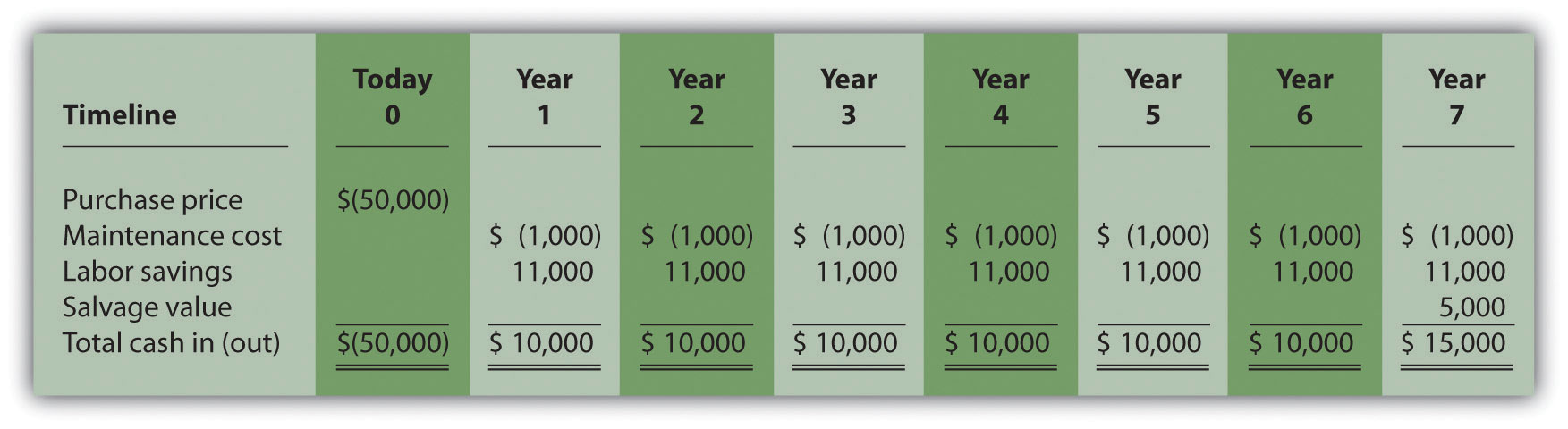

Answer: The payback period is five years. Here’s how we calculate it. Figure 8.6 "Summary of Cash Flows for Copy Machine Investment by Jackson’s Quality Copies" repeats the cash flow estimates for Julie Jackson’s planned purchase of a copy machine for Jackson’s Quality Copies, the example presented at the beginning of the chapter.

Figure 8.6 Summary of Cash Flows for Copy Machine Investment by Jackson’s Quality Copies

The payback method answers the question “how long will it take to recover my initial $50,000 investment?” With annual cash inflows of $10,000 starting in year 1, the payback period for this investment is 5 years (= $50,000 initial investment ÷ $10,000 annual cash receipts). This calculation is relatively simple when one investment is made at the beginning, and annual cash inflows are identical. However, some investments require cash outflows at different points throughout the life of the asset, and cash inflows can vary from one year to the next. Table 8.1 "Calculating the Payback Period for Jackson’s Quality Copies" provides a format to help calculate the payback period for these more complex investments. Note that the review problem at the end of this segment provides an example of how to calculate the payback period to the nearest month when uneven cash flows are expected.

Table 8.1 Calculating the Payback Period for Jackson’s Quality Copies

| Investment (Cash Outflow) | Cash Inflow | Unrecovered Investment Balance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year 0 | $(50,000) | - | $(50,000)a |

| Year 1 | - | $10,000 | (40,000)b |

| Year 2 | - | 10,000 | (30,000)c |

| Year 3 | - | 10,000 | (20,000) |

| Year 4 | - | 10,000 | (10,000) |

| Year 5 | - | 10,000 | 0 |

| Year 6 | - | 10,000 | 0 |

| Year 7 | - | 15,000 | 0 |

|

a $(50,000) = $(50,000) initial investment. b $(40,000) = $(50,000) unrecovered investment balance + $10,000 year 1 cash inflow. c $(30,000) = $(40,000) unrecovered investment balance at end of year 1 + $10,000 year 2 cash inflow. |

|||

Weaknesses of the Payback Method

Question: Why is it a problem to ignore the time value of money when calculating the payback period?

Answer: Suppose you have 2 investments of $10,000 to choose from. The first investment generates cash inflows of $8,000 in year 1, $2,000 in year 2, and $1,000 in year 3. The second investment generates cash inflows of $2,000 in year 1, $8,000 in year 2, and $1,000 in year 3. The two investments are summarized here:

| Investment I | Investment II | |

| Year 0 | $(10,000) | $(10,000) |

| Year 1 | 8,000 | 2,000 |

| Year 2 | 2,000 | 8,000 |

| Year 3 | 1,000 | 1,000 |

Both investments have a payback period of two years. Does this mean both investments are of equal value? No because the first investment generates far more cash in year 1 than the second investment. In fact, it would be preferable to calculate the IRR to compare these two investments. The IRR for the first investment is 6 percent, and the IRR for the second investment is 5 percent.

Question: Why is it a problem to ignore the cash flows after the payback period?

Answer: Suppose $50,000 can be invested in 2 separate investments with the following cash flows:

| Investment I | Investment II | |

| Year 0 | $(50,000) | $(50,000) |

| Year 1 | 25,000 | 2,000 |

| Year 2 | 25,000 | 2,000 |

| Year 3 | 3,000 | 46,000 |

| Year 4 | 0 | 35,000 |

The first investment has a payback period of two years, and the second investment has a payback period of three years. If the company requires a payback period of two years or less, the first investment is preferable. However, the first investment generates only $3,000 in cash after its payback period while the second investment generates $35,000 after its payback period. The payback method ignores both of these amounts even though the second investment generates significant cash inflows after year 3. Again, it would be preferable to calculate the IRR to compare these two investments. The IRR for the first investment is 4 percent, and the IRR for the second investment is 18 percent.

Although the payback method is useful in certain situations where companies are concerned about recovering investments as quickly as possible (e.g., companies on the verge of bankruptcy), it is not a measure of profitability. The NPV and IRR methods compare the profitability of each investment by considering the time value of money for all cash flows related to the investment.

Wrap-Up of Chapter Example

In the Jackson’s Quality Copies example featured throughout this chapter, the company is considering whether to purchase a new copy machine for $50,000. A week has passed since Mike Haley, accountant, discussed this investment with Julie Jackson, president and owner. Refer to Figure 8.2 "NPV Calculation for Copy Machine Investment by Jackson’s Quality Copies", Figure 8.4 "Alternative NPV Calculation for Jackson’s Quality Copies", and Figure 8.5 "Finding the IRR for Jackson’s Quality Copies", and Table 8.1 "Calculating the Payback Period for Jackson’s Quality Copies" as you learn what Mike’s findings are.

| Julie: | Hi Mike, any news on the copy machine proposal? |

| Mike: | I ran the numbers for the new copy machine, and I think you’ll like the results. It’s not as simple as looking at the difference between cash outflows of $57,000 and cash inflows of $82,000 over the life of the asset. We also have to see when the cash flows occur and convert them into today’s dollars. |

| Julie: | OK. What did you find? |

| Mike: | The NPV is $1,250 using a required rate of return of 10 percent. This means the investment will generate a return of more than 10 percent after converting the cash flows into today’s dollars. |

| Julie: | Great! I realize the return is expected to be above 10 percent. Do you have a sense of how far above 10 percent? |

| Mike: | Yes. The IRR is about 11 percent. I also calculated the payback period to give you an idea of how long it will take to recover our initial $50,000 investment. |

| Julie: | Good idea. My hope is that we won’t be waiting too long to recover the original investment. |

| Mike: | It will take 5 years to fully recover the $50,000 investment. |

| Julie: | Wow! That seems like a long time. |

| Mike: | It is. But realize we bring in an additional $25,000 after the payback period. Also, the payback method does not measure the profitability of the investment, it simply tells us how long before the initial investment is recovered. Unless we anticipate cash flow problems, I wouldn’t place too much importance on the payback period. The NPV and IRR calculations are the best for evaluating this investment. |

| Julie: | Good point. We don’t expect to have cash flow problems. We have plenty of capital, and the business has generated positive cash flow for the past 10 years. Let’s order the new machine! |

Business in Action 8.4

Capital Budgeting at Fortune 1000 Companies

Studies completed over the past 40 years have indicated that managers prefer to use IRR and payback methods over NPV when evaluating long-term investments. However, a recent survey of Fortune 1000 chief financial officers indicates that NPV is now the most preferred method. According to this survey, the percentage of firms that always or often use each method is as follows:

| NPV | 85 percent |

| IRR | 77 percent |

| Payback | 53 percent |

This survey also shows that companies with capital budgets exceeding $500,000,000 are more likely to use these methods than are companies with smaller capital budgets. This is probably because larger companies have more specialized personnel in their finance and accounting departments, which enables them to use more sophisticated approaches in evaluating long-term investments.

Source: Patricia A. Ryan and Glenn P. Ryan, “Capital Budgeting Practices of the Fortune 1000: How Have Things Changed?” Journal of Business and Management 8, no. 4 (2002).

Key Takeaway

- The payback method evaluates how long it will take to “pay back” or recover the initial investment. The payback period, typically stated in years, is the time it takes to generate enough cash receipts from an investment to cover the cash outflow(s) for the investment. Although this method is useful for managers concerned about cash flow, the major weaknesses of this method are that it ignores the time value of money, and it ignores cash flows after the payback period.

Review Problem 8.5

This review problem is a continuation of Note 8.22 "Review Problem 8.3" and Note 8.26 "Review Problem 8.4" and uses the same information. The management of Chip Manufacturing, Inc., would like to purchase a specialized production machine for $700,000. The machine is expected to have a life of 4 years and a salvage value of $100,000. Annual maintenance costs will total $30,000. Annual labor and material savings are predicted to be $250,000.

- Use the format in Table 8.1 "Calculating the Payback Period for Jackson’s Quality Copies" to calculate the payback period. Clearly state your conclusion.

- Describe the two major weaknesses of the payback method.

Solution to Review Problem 8.5

-

The payback period is slightly more than three years since only $40,000 is left to be recovered after three years, as shown in the following table.

Investment (Cash Outflow) Cash Inflow Unrecovered Investment Balance Year 0 $(700,000) - $(700,000) Year 1 - $220,000a (480,000) Year 2 - 220,000a (260,000) Year 3 - 220,000a (40,000) Year 4 - 320,000b 0 a $220,000 = $250,000 annual savings – $30,000 annual costs.

b $320,000 = $250,000 annual savings – $30,000 annual costs + $100,000 salvage value.

A more precise calculation can be performed assuming the $220,000 cash inflow for year 4 occurs evenly throughout the year and the $100,000 salvage value cash inflow occurs at the end of year 4. With these assumptions, we simply need to calculate how many months are required in year 4 to recover the remaining $40,000. $40,000 divided by $220,000 equals 0.18 (rounded). Thus 0.18 of a year, or approximately 2 months (= 0.18 × 12 months), is required to recover the remaining $40,000. This more precise calculation results in a payback period of three years and two months. Note that the salvage value is ignored as this cash inflow occurs at the end of year 4 when the machine is sold.

- First, the payback method does not consider the time value of money (no present value or IRR calculations are performed). Second, it only considers the cash inflows until the investment cash outflows are recovered; cash inflows after the payback period are not part of the analysis. For Chip Manufacturing, Inc., the payback period is three years and two months. However, significant cash inflows totaling $280,000 occur after the payback period and therefore are ignored ($280,000 = $320,000 year 4 cash inflows – $40,000 remaining investment recovered in the first 2 months of year 4).