This is “The New Deal and Origins of World War II, 1932–1939”, chapter 7 from the book United States History, Volume 2 (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 7 The New Deal and Origins of World War II, 1932–1939

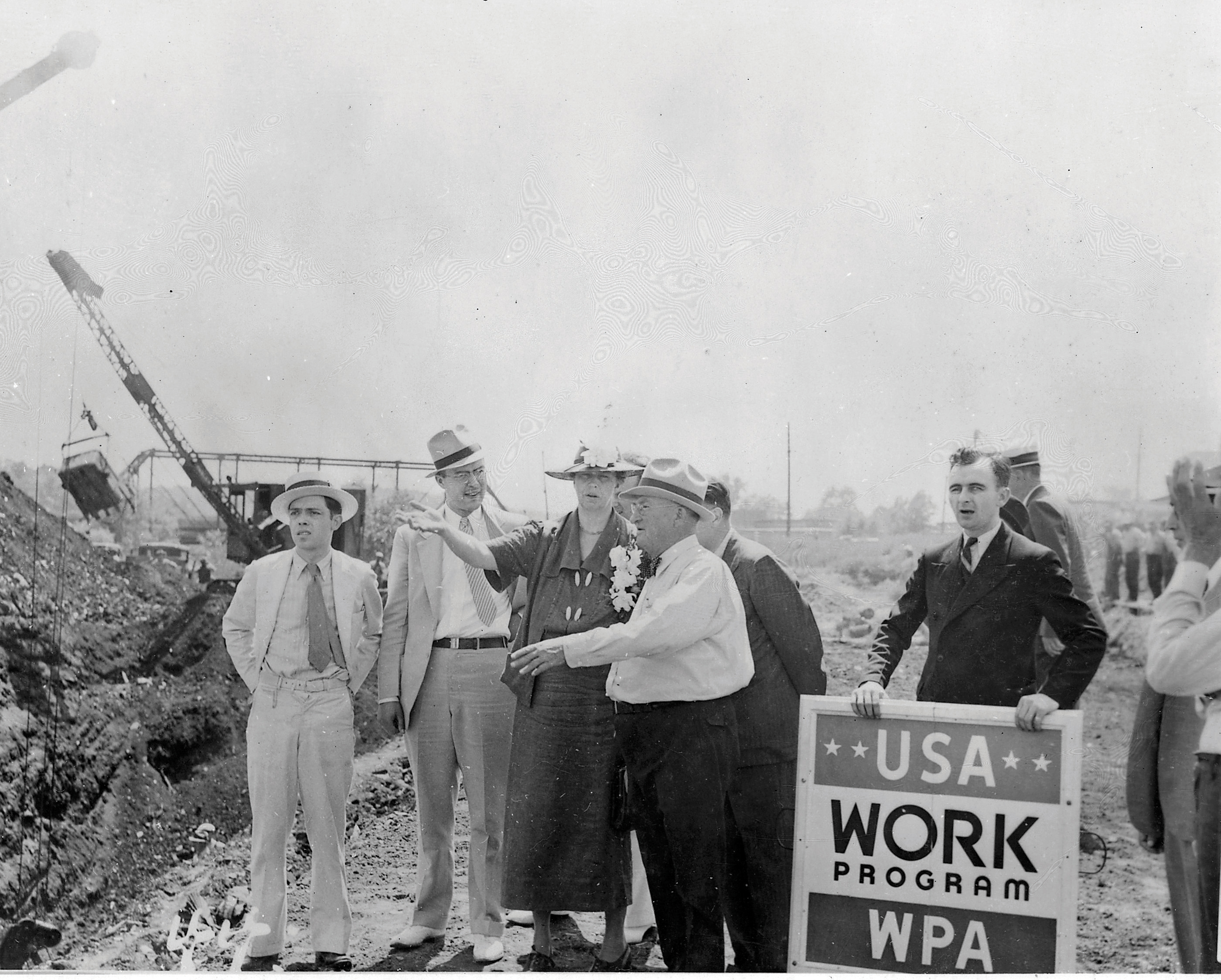

Figure 7.1

World War I veterans returned to the nation’s capitol as Roosevelt took office, seeking early payment of their enlistment bonus. Although neither President Hoover nor Roosevelt agreed to meet with the men, Eleanor Roosevelt and a number of congressmen did. In this photo, Texas congressman Wright Patman and Mississippi’s John Rankin collect petitions from members of the Bonus Army.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) inherited a banking system on the verge of collapse and an economy where 12 million job-seekers could not find work. The stock market had declined by over 80 percent, while average household income was just above half of what it had been in the late 1920s. The scale of human suffering was particularly devastating for the 2 million families who lost homes and farms and the 30 million Americans who were members of households without a single employed family member. Perhaps most frustrating was that one in five children was chronically malnourished, while US farms continued to produce more food than the nation could possibly consume. Prices for some farm goods remained so low that millions of tons of food were wasted because it cost more to transport certain items than they would generate in revenue if sold. A similar tragedy existed in the form of warehouses that remained full of coats and other necessities, while millions of Americans lacked the ability to purchase them at nearly any price.

The nation wondered how their new president would fulfill his promise to relieve the suffering and get the nation back to work. Roosevelt had promised a “New Deal” but offered few details of how that deal would operate. In May 1933, a small group of veterans of the Bonus Army decided to return to Washington and see for themselves if the new president would be any more supportive of their request for an early payment of their WWI bonuses. He was not. In fact, three years later, Roosevelt would veto a bill providing early payment, a bill Congress eventually passed without his signature.

However, in 1933, Roosevelt’s treatment of the men and their families showed a degree of compassion and respect that demonstrated Roosevelt had at least learned from the public outrage regarding Hoover’s treatment of the Bonus Army. Rather than call out the army, Roosevelt provided tents and rations. Eleanor RooseveltA leading public figure who assisted her husband’s rise through New York and national politics, Roosevelt also transformed the position of presidential spouse. She traveled and advocated a number of liberal causes from women’s rights to civil rights. The president supported some of these causes, but feared his direct advocacy of controversial subjects such as civil rights would jeopardize his electoral support. Because of her popularity, Eleanor Roosevelt’s conferences were covered by every major news outlet and her decision to only admit female reporters to these conferences created many new opportunities for women in journalism. met with the men and promised that the administration would eventually find them jobs. She kept her promise, as World War I veterans were recruited for jobs in new government programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps. Although this particular program was limited to those below the age of twenty-five, veterans were exempt from the age requirement. One of the veterans was said to have offered a simple comparison that reflected the difference between the two presidents. “Hoover sent the army,” the oft-quoted remark began, “Roosevelt sent his wife.” Those who know Eleanor Roosevelt understand that she likely met with the veterans on her own initiative. On this and many occasions, the president demonstrated his wisdom by at least partially deferring to the judgment of his most talented advisor.

7.1 The First New Deal, 1933–1935

Learning Objectives

- Explain how President Roosevelt stabilized the banking sector. Identify the changes to the banking and investment industry that occurred between 1933 and 1935.

- Summarize each of the leading New Deal agencies that were created in the first years of the New Deal. Explain how the role of the federal government changed between 1933 and 1935, using these programs as examples.

- Analyze the federal government’s attempts to create a more ordered economy through the National Recovery Administration. Explain how the government sought to mitigate conflicts between industry and labor, as well as the reasons why the Supreme Court declared the NRA to be unconstitutional.

The Banking Crisis

The provisions of the Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution shortened the time period between the November election and inauguration of the president from March 4 to January 22. This interim was known as the “lame duck” period and featured several months where the outgoing president remained in office. Because the Twentieth Amendment would not take effect until 1933, Hoover continued to preside over a nation whose banking system was teetering toward collapse.

An assassin’s bullet just missed president-elect Roosevelt in February of that year, instead killing Chicago mayor Anton Cermak while the two men were talking. Cermak’s death was mourned by Chicagoans and supporters of Progressivism nationwide. The Czech immigrant had risen through Chicago politics and defeated the Republican machine that was operated by city boss “Big Bill” Thompson. Thompson’s political machine had dominated the city in previous decades and was allegedly connected to organized crime figures such as Al Capone. Cermak reportedly turned to Roosevelt after the bullet hit him and said that he was glad the new president had been spared. While this mythical expression of the nation’s support for their president-elect became legend, most Americans were skeptical that their future leader was up to the challenge before him.

The new president still had not offered many specific details of how he planned to combat the Depression, and news of political gamesmanship between the outgoing and incoming presidents concerned the nation. Communications between Hoover and Roosevelt were full of posturing and intrigue. Hoover insisted that any meeting be held at the White House—a not-so-subtle reminder that he was still the president. Roosevelt wanted Hoover to meet him outside of the White House for similar prideful reasons. Hoover sought Roosevelt’s endorsement of several of his plans, a defensible request given the impending transfer of power. However, Roosevelt was suspicious that Hoover’s apparent goodwill was really an attempt to transfer responsibility for any consequences onto the new president. By Hoover’s perspective, Roosevelt’s intransigence was a political calculation based on making sure the nation’s economy did not turn the corner until he took office. The tragic result was that little was accomplished in the months between the election and Roosevelt’s inauguration.

Figure 7.2

Hoover and Roosevelt sit together on Inauguration Day. As the photo indicates, the two men shared reservations toward each other and did not work together during the period between the election and Roosevelt’s inauguration.

Bank foreclosures and bank failure did not wait for Inauguration Day. Every state placed restrictions preventing depositors from withdrawing more than a certain amount or a percentage of their holdings each day. Some areas suspended banking operations completely in an attempt to keep the entire system from imploding. Upon assuming office, the president declared his first priority was to restore order in the banking system. He announced that all banks would close for a four-day “holiday” while Congress met in an emergency session. Roosevelt assured the American people that the “nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror” that gripped the nation was the only thing they needed to fear. The nation’s factories and farms were still productive, the president reminded his listeners. These productive centers had fueled the growth of America and would continue to do so if only they could recover from the financial instability that was born of uncertainty rather than any fundamental flaw in their design, the nation’s infrastructure, or the national character.

The president’s Emergency Banking Relief BillA law granting federal examiners the authority to examine the records of banks and determine which institutions were financially sound. All banks that passed this examination were permitted to reopen with the added security of the federal government’s commitment to provide additional funds if needed to ensure the financial stability of the bank. helped to restore confidence by pledging federal backing of the nation’s banking system. The bill was passed by unanimous consent in the House and by an overwhelming margin in the Senate on March 9, 1933. Due to the pervasive sense of emergency at that time, there was very little debate on the bill and most legislators never even read the legislation. However, most legislators understood and supported the fundamental changes to the banking system that would result. The new law granted the government the power to evaluate the financial strength of each bank. Those banks that passed inspection were allowed to receive unsecured loans from the federal government at low interest rates to help them through the crisis. The law also granted the federal government the authority to reorganize and reopen banks. Most importantly, Roosevelt committed the federal government to provide loans to banks to prevent them from failing.

The emergency law did not yet create the explicit guarantee of federal insurance for banks, although this guarantee would be part of legislation that would be passed later in Roosevelt’s term. However, the president delivered a well-conceived speech that was broadcast throughout the country. In this address, Roosevelt explained how the emergency law would prevent bank failures in the near term. The president’s radio address succeeded as banks reopened to long lines of depositors—a welcome sight given the recent history of panicked crowds waiting outside banks to withdraw funds. Conservatives and business interests were relieved that the president had used the power of the federal government to bolster the existing financial system rather than seek more radical change. Consumers were equally pleased to find that the government would take steps to protect the money they deposited in banks. The sudden wave of depositors also demonstrated the trust most Americans still had in government and the basic infrastructure of America’s financial system. Roosevelt would continue to use radio addresses, which he later dubbed “fireside chats,” to explain his policies directly to the people.

Figure 7.3

President Roosevelt sought to explain his policies directly to the public through a series of radio addresses he called “fireside chats.”

At the same time, Congress’s ready acceptance of a sweeping law that effectively gave the Roosevelt administration control over the fate of every private bank in the nation alarmed some observers. Even those who favored the banking bill worried that the balance of power between the executive and legislative branches had shifted in ways that could lead to unintended consequences. In addition, over one hundred members of the legislature were newly elected Democrats unaccustomed to Washington politics and perhaps overly eager to support the Roosevelt administration. Roosevelt’s unassuming personality and apparent sincerity helped to reduce this criticism, but not all in Washington or in the nation supported the new president. Others who were more skeptical had grown so frustrated by the perceived inaction of the previous years that they seemed willing to let Roosevelt and the Democrat-controlled Congress try anything.

Roosevelt enjoyed Democratic majorities in both the Senate and the House, and so in 1933, his critics could do little but warn of the possibility that the new president might abuse his powers. This message of warning and dissent remained largely in the background until 1937 when the economic recovery of the president’s first term crumbled in the midst of a second Wall Street crash. Until that time, Roosevelt sought to create goodwill among the various interests of labor and capital by inviting representatives of unions and businesses to help shape legislation. Throughout his first four years in office, Roosevelt enjoyed widespread popular support. Although he was able to pass nearly every one of the laws his advisors recommended during these years, securing lasting economic recovery would prove more difficult for the new president.

The First Hundred Days

The emergency banking bill was merely the first of many sweeping changes the Roosevelt administration guided through Congress in the one hundred days between March 9 and June16, 1933. Together with other bills passed during the subsequent sessions of Congress between 1934 and 1936, Roosevelt created the basis of what would later be known as the New DealA series of economic reforms and programs that were supported by the Roosevelt administration and approved by Congress during Roosevelt’s first term. These programs sought to stabilize the banking industry and monetary and agricultural markets and provide temporary jobs.. For the first one hundred days of his administration, and for his first three years in office, nearly every proposal Roosevelt endorsed and sent to the floor of Congress was passed by large majorities. Not since George Washington had a US president enjoyed such influence over his nation’s government. For some, even the depths of the Great Depression could not justify the concentration of so much power into the hands of one man.

Part of the reason Congress went along with Roosevelt was that the changes his administration introduced were not as radical as his critics had feared. Roosevelt refused to consider having the federal government take direct control of banks or factories—a strategy known as nationalization that would become common in Socialist nations and dictatorships. Roosevelt sought advice from a rather conservative-minded group of well-educated and successful individuals. Known informally as the “Brains Trust,” Roosevelt’s informal advisers shared the perspective and background of other influential leaders in business and hoped to reform rather than replace the nation’s economic system.

Representing the best and the brightest in many fields, Roosevelt’s advisers offered a variety of ideas. The president tried nearly all of them in one form or another. In addition to this informal advisory team, Roosevelt appointed a number of well-qualified individuals to his cabinet. Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins and Interior Secretary Harold IckesSecretary of the Interior and one of the most influential members of the Roosevelt administration, Ickes was overseer of various federal works projects and supported greater autonomy for Native American tribes. were two of the most influential cabinet members, and many of the strategies the president attempted were those supported by Perkins and Ickes.

Figure 7.4

Frances Perkins was an influential member of Roosevelt’s cabinet and one of the architects of the New Deal as the secretary of labor.

Frances PerkinsThe longest-serving Secretary of Labor and the first woman in the cabinet, Perkins skillfully represented the concern of labor leaders within the administration. Although she often worked to secure the support of business leaders, she was consistent in her belief of the right of workers to bargain collectively with their employers. was able to secure the support of organized labor behind the president’s plans while also finding support among the leading business men of her day. Ickes administered the public face of the New Deal—government-funded construction projects meant to provide jobs while developing the nation’s infrastructure. Although each of the New Deal Programs Roosevelt’s advisers championed represented a fundamental change in the expectations of the federal government, many of them were also similar to those being considered by the Hoover administration in the year before Roosevelt’s inauguration. The crucial difference was that under Roosevelt, federal programs to stimulate the economy operated on a much more ambitious scale.

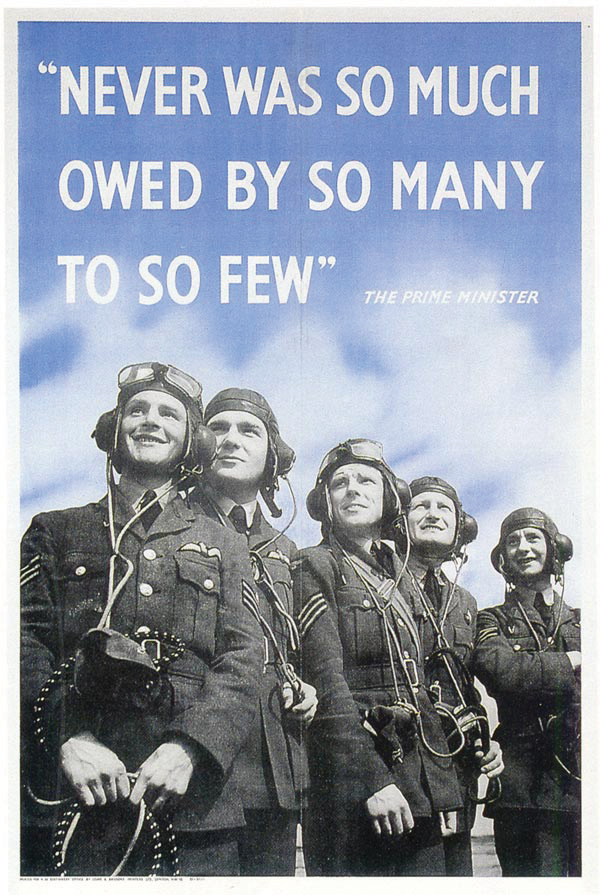

By the mid-1930s, the federal government was borrowing hundreds of millions of dollars each year. One-third of the federal budget was spent on public employment projects and relief for the poor. At the same time, federal budget deficits still represented a relatively small percentage of the GDP (gross domestic product)—the total market value of all goods and services produced each year. Federal spending during the Depression was certainly greater than any peacetime period in the nation’s history, but it still represented only a fraction of what the government spent during World War I. In addition, the US government would spend more in one year fighting World War II than was spent funding every New Deal program combined.

However, throughout its history the nation had tolerated large deficits and the expansion of government power during wartime and expected contraction and thrift during peacetime. The idea that the government should borrow money and provide direct employment during recessions and depressions had been raised since the 1830s but had never been seriously considered by federal leaders until the beginning of the Great Depression. For example, during a recession at the turn of the century, a group of men called Coxey’s Army marched to Washington asking the government to borrow money to provide jobs for the unemployed. These men were branded as radicals, and leaders such as Jacob Coxey were arrested. Keeping this background in mind, one can see why each of the following programs approved during Roosevelt’s first one hundred days reflected a very different way of viewing the role of the federal government.

- March 20: The Economy Act sought to reduce the budget deficit by reducing government salaries by an average of 15 percent and also enacted cuts to pensions of federal employees including veterans.

- March 22: The Beer and Wine Revenue Act amended the Volstead Act by permitting the production and sale of wine and beer that possessed alcohol content no greater than 3.2 percent. These products were subjected to special taxes, thereby increasing government revenue and decreasing the expense related to federal enforcement of prohibition. Congress also approved the Twenty-First Amendment, which repealed the Eighteenth Amendment and officially ended prohibition when the last state required to ratify the amendment did so in December 1933.

- March 31: The Emergency Conservation Work Act created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which provided a total of 2 million jobs for young men from 18 to 25 between its creation and America’s entry into World War II. The CCC usually employed 250,000 men at any point in its history and developed state and national parks. CCC workers also worked on hundreds of conservation projects and planted an estimated 3 billion trees. Many participants were able to take vocational courses or earn their high-school diplomas. The men earned wages of $30 per month and most expenses associated with room and board. Of their wages, $25 was sent directly home to their families.

Figure 7.5

Young men at work building a trail as part of a Civilian Conservation Corps project. The CCC employed young men between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five, as well as a number of veterans of all ages who needed work.

- April 19: The United States temporarily abandoned the gold standard, which permitted more money to be circulated. This action helped to stabilize commodity prices, which pleased farmers and helped to ensure stability in food production and distribution. At the same time, critics suggested that abandoning the gold standard would reduce domestic and international faith in the strength of the dollar and lead to inflation. However, consumer prices remained low throughout the Depression.

- May 12: The Federal Emergency Relief Act created the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), which increased the funds available to states under Hoover’s plan. It also altered these funds from loans that must be repaid to federal grants. Although some FERA funds were used for direct cash payments, most of the $3 billion that was provided to the states was used to provide jobs in various public works projects. Roosevelt and those in Congress hoped to avoid creating a regular schedule of direct cash payments to individuals, a practice that was known as “the dole” in the states and cities that offered such payments. The dole was similar to modern welfare payments and carried the same negative stigma during the 1930s as it would in modern times. However, creating jobs required a much larger initial investment, and it would not be until the creation of the Works Progress Administration of 1935 (WPA) that the federal government would offer substantial funding for public works projects as the primary source of direct relief to the unemployed. FERA operated between 1933 and 1935.

- May 12: The Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) farm income had declined substantially between 1929 and 1932 as a result of overproduction and declining prices. The AAA sought to stabilize prices by offering payments to farmers who agreed to not maximize their production. The funds for these payments were to be raised by a tax on processors of agricultural commodities such as cotton gins or mills. Congress also passed the Emergency Farm Mortgage Act, which facilitated the refinancing of farm loans.

- May 18: The Tennessee Valley Authority Act created the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and authorized federal funds for the creation of hydroelectric dams and other projects meant to provide employment and promote development within one of the most economically distressed regions.

- May 27: The Federal Securities Act established legal standards for disclosure of information relevant to publicly traded securities such as stocks and bonds. Together with subsequent legislation, the federal government established the Securities and Exchange Commission, which regulated the investment industry.

- June 13: The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Act established the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, which provided refinancing for home mortgages much like the government offered to farmers. This agency refinanced one in five US homes, providing lower interest rates and lower monthly payments that permitted millions of American families to avoid foreclosure and possible homelessness.

- June 16: The Glass-Steagal Banking Act established the Federal Deposit Insurance Commission (FDIC) that regulated the banking industry and provided federal insurance for many kinds of bank deposits. The act also separated commercial banking, investment banking, and insurance by prohibiting any single company from providing all of these services and prohibiting officers of an investment firm to also have a controlling interest in a bank or insurance company. These conflict of interest provisions were repealed in 1999.

- June 16: The National Industrial Recovery Act was a two-part law creating the Public Works Administration (PWA) and the National Recovery Administration (NRA). The PWA allocated a total of $6 billion in private contracts to build bridges, dams, schools, hospitals, and vessels for the navy during the Depression. The NRA was much more controversial as it established trade unions in various industries that drafted their own rules regarding prices and production. These trade unions often operated as cartels that were controlled by the largest corporations in each industry, despite the ostensible government regulation and participation of labor representatives. The Supreme Court declared the NRA to be an unconstitutional use of government power in May 1935.

Industry and Labor

The New Deal, like all major legislative reforms, was not simply concocted by members of the Roosevelt administration. Its provisions were the result of hundreds of grassroots initiatives by union workers and the unemployed who created the New Deal through participation in local, state, and national politics. For example, rank-and-file workers in Chicago created and participated in many organizations that communicated their ideas to local government leaders. For the first time in the city’s history, the majority of these organizations were not based around ethnicity or a particular craft. Instead, they represented ideas and perspectives that crossed these fault lines that had divided workers in the past.

Support for the federal government directly providing jobs for the unemployed or arbitrating conflicts between labor and management had been building for several generations. The Great Depression led to an increased level of activism among workers who believed that the federal government must intervene on behalf of the common citizen. Local political machines had failed to insulate cities and states from the Depression, while the paternalism and generosity of welfare Capitalism displayed its limits. For example, in 1931, Henry Ford blamed the Depression on the character faults of workers. “The average man won’t really do a day’s work unless he is caught and cannot get out of it,” Ford declared. Later that same year, Ford laid off 60,000 workers at one of his most productive plants.

Private industry and banks were unable to stimulate recovery, and many leading businessmen beyond Henry Ford seemed indifferent to the plight of workers. In response, the Roosevelt administration became more willing to consider the perspectives of the unemployed and the poor. At the same time, Roosevelt was a member of the upper class and shared many of the same conservative beliefs regarding the role of government, as did business leaders and previous presidents. Like Hoover, Roosevelt was an outspoken opponent of expanding the dole—the epithet applied to state and local welfare programs that distributed food and money directly to the needy. He was also sensitive to the ideas of industry and believed that the only way out of the Depression was to create a more favorable business environment through government intervention.

The Roosevelt administration looked toward the War Industries Board of the previous decade as a model for how to achieve both greater prosperity and increased production. Government planning had worked during World War I, Roosevelt’s advisers believed, arguing that government intervention could also help revive several industries where prices had declined below the point of profitability. Representatives of workers and the unemployed also convinced Roosevelt that public works projects were necessary to provide immediate employment until the economy and the private sector recovered.

As a result, the New Deal sought to promote two objectives. First, it would provide “workfare” rather than welfare by offering short-term employment in public works projects. Second, it would seek to create a more well-ordered economic system that encouraged the recovery of the private sector in the long run. Key to the operation of this system would be the incremental termination of federal public works programs once private industry began to recover. If government employment continued too long, they believed, these federal programs would compete for workers and prevent America’s factories from fully recovering and resuming full production.

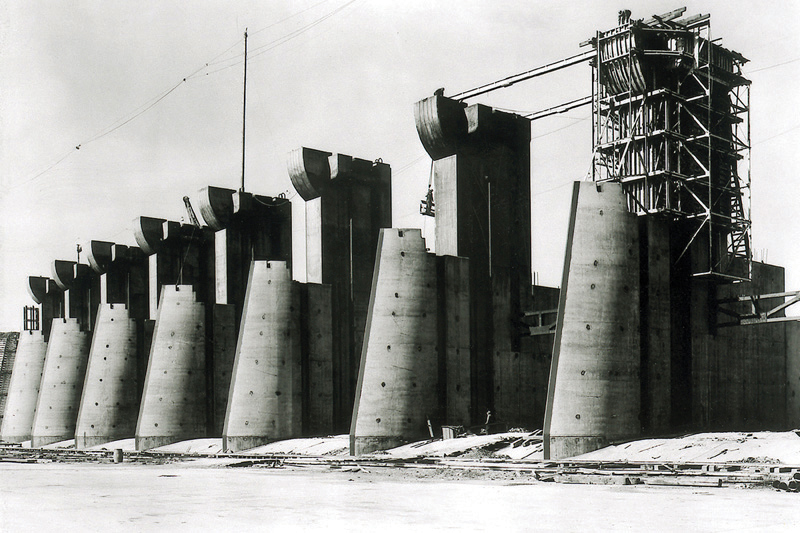

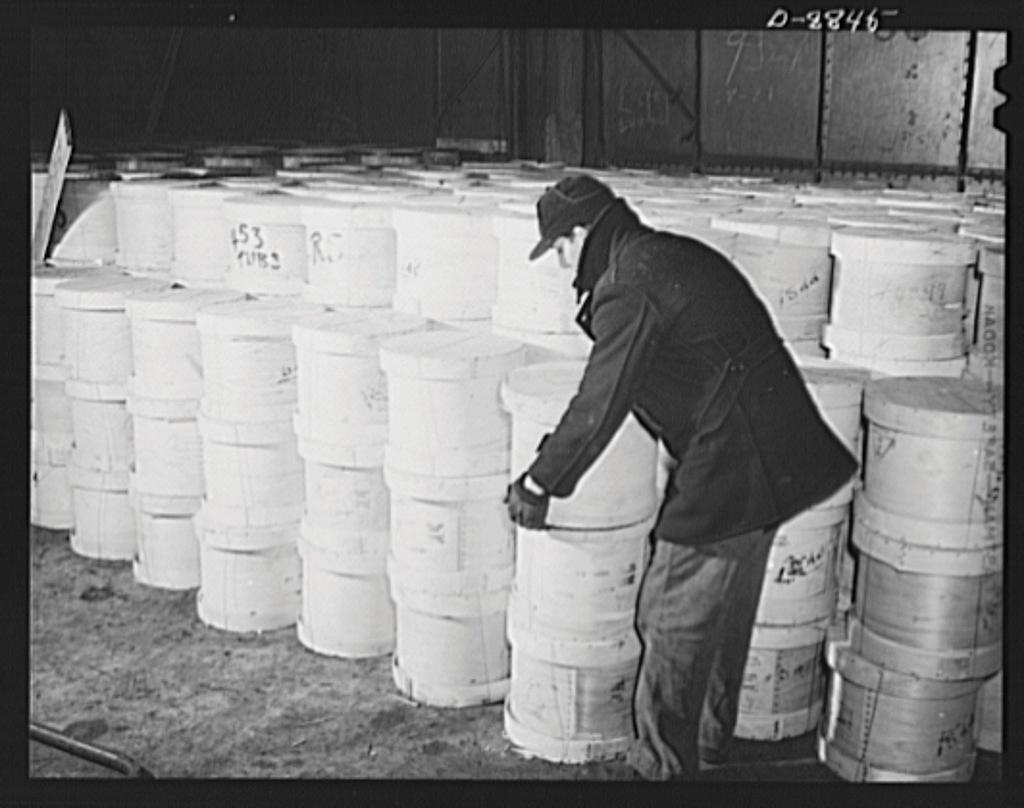

Representing these twin goals of relief through public employment and recovery through economic planning, the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) created two massive agencies. The Public Works Administration (PWA)Created by the National Industrial Recovery Act, the PWA was a federal works program that generally worked with private contractors to create major public works projects. would oversee Roosevelt’s “workfare” relief program with a budget of $3 billion in its first year. The PWA contracted with private construction firms to build a variety of public works projects. Among the projects of the PWA were the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington State, the Lincoln Tunnel connecting New Jersey with New York City, the Overseas Highway connecting the Florida Keys, and the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. Although many doubted the usefulness of air power at the time, the PWA’s decisions to build the aircraft carriers Enterprise and Yorktown would later prove to be two of the most important decisions made during the New Deal.

The second provision of NIRA soon became both the most ambitious and most controversial program of the entire New Deal. The National Recovery Administration (NRA)Also created by the National Industrial Recovery Act, the NRA sought to create trade unions representing various industries that would create codes regulating wages, prices, and production. The goal was to provide a more ordered economy and eliminate overproduction that led to unnaturally low prices and low wages. Critics suggested that the NRA created cartels controlled by the largest firms to reduce production while increasing prices. The NRA was declared unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court in 1935. created planning councils that established codes governing each industry. For example, the automotive trade council was led by representatives of major car manufacturers, labor unions, and government officials. Together, this council would determine how many and what types of automobiles would be built, the prices of these vehicles, minimum wages, and other provisions that would guarantee both profitability and the well-being of workers.

The central idea behind the NRA was that without these quotas and minimum standards, car manufacturers (and other businesses) would continue to engage in cutthroat competition with one another. This was important because the Depression decreased the number of consumers to the point that manufacturers were forced to sell their products at or below cost. NRA supporters believed that industry-wide coordination and planning would ensure that manufacturers only produced the number of products that would sell at a predetermined price. Included in this price was a reasonable profit that would permit employers to pay their workers a better wage. In return, employees of these companies could enjoy a measure of financial security and once again become consumers whose discretionary spending had fueled the growth of the 1920s.

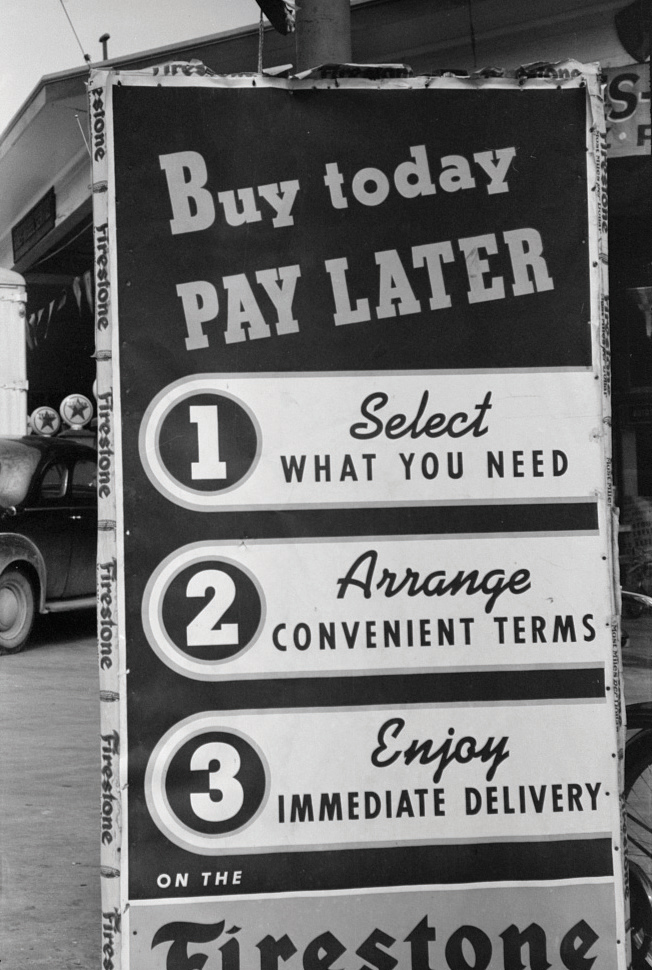

Although this kind of central planning might be well-intentioned, many Americans feared that unintended consequences would occur. They feared that planning councils would be controlled by a few corporations within each industry, thereby creating cartels that could operate without any fear of competition. Such a system would permit manufacturers to keep production so low that prices could be increased dramatically. If this occurred, the result would be large profits for industries that intentionally limited production in ways that prevented job growth. Others feared the government would control these planning councils, promoting the growth of Socialism. Defenders of the NRA argued that neither cartelization nor Socialism would develop so long as each council shared power between heads of industry, labor unions, and government regulators. Government planning had worked in World War I, they argued, while the ruinous competition of the unregulated free market had led to the excesses of the 1920s and would likely prolong the current Depression. Equally important, NRA defenders argued, was the fact that participation in the NRA was voluntary. The decisions of planning councils were merely codes rather than law, and businesses were still free to practice free market principles if they did not like the codes in their industry. However, refusal to participate in the NRA was not without its own consequences. Only those businesses that participated could display the NRA’s Blue Eagle in their storefronts and on their products. Failure to participate in the NRA was considered unpatriotic, and the government suggested consumers boycott any business that rejected the NRA’s codes.

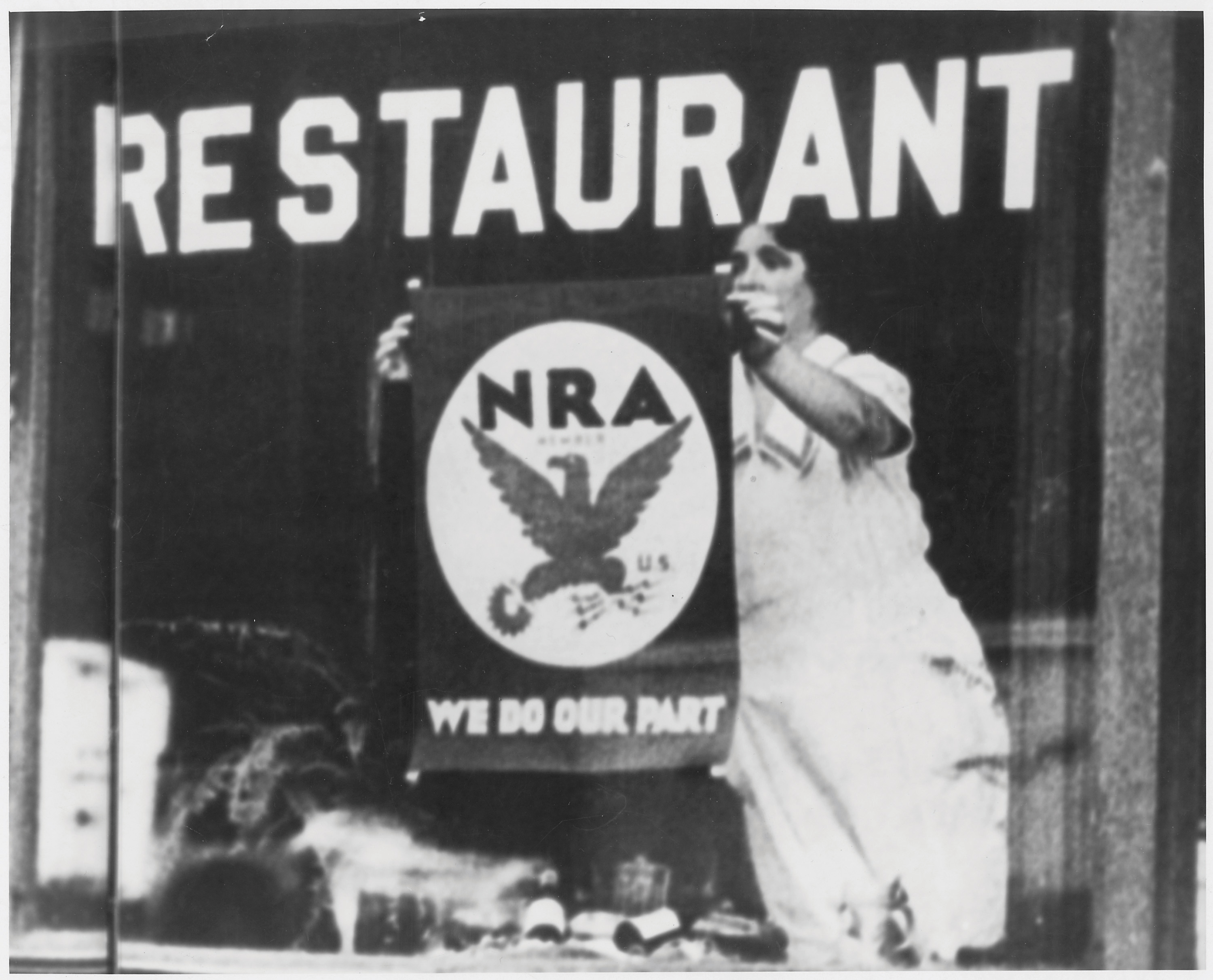

Figure 7.6

Participation in the NRA was voluntary, but only businesses that followed the codes in their industry could display the Blue Eagle Emblem on their products or in their stores.

Volunteerism could only be effective if the majority of businesses in any given industry participated in or at least abided by the decisions of the NRA’s planning councils. In the first years of the NRA, most industries did participate. However, this level of participation was only achieved by allowing the largest companies in any industry to draft codes allowing them to reduce production and increase prices. While this might encourage stability, critics argued that the NRA was actually preventing economic recovery while violating free market principles. In 1935, the Supreme Court agreed with the critics of the NRA, who argued that the agency violated principles of limited government and free enterprise and placed too much power in the hands of the federal government.

Although the NRA was ruled unconstitutional, it inspired a number of important changes. To provide more jobs for heads of households, the NRA prohibited child labor and set the workweek at forty hours. The NRA also included minimum wages and required companies to pay 150 percent of a worker’s normal hourly wage for every hour he or she worked beyond forty hours. Each of these measures had long been goals of the labor movement. Although the forty-hour week and overtime pay were merely codes and not laws, they were now supported by the federal government. The main reason the government supported these measures was to encourage businesses to hire more workers as a means of reducing unemployment.

Subsequent legislation in Roosevelt’s first year included the creation of the Civil Works Administration (CWA). The CWA provided federal jobs for 4 million Americans between its creation in November 1933 and its termination only four months later. The majority of CWA workers were employed in small-scale construction and repair jobs, but the CWA also hired teachers in economically depressed areas. Critics charged the CWA with providing needless jobs, such as raking leaves in parks. Given the speed with which the CWA payroll grew and the lack of a bureaucratic structure to secure the needed planning and resources for meaningful projects, such criticism was often well placed. The program’s expenses grew faster and larger than the Roosevelt administration had anticipated until the CWA was eliminated in March 1934. However, the CWA would serve as a model for future projects by directly employing workers rather than operating through private contractors. At the same time, it provided a cautionary tale about the need for planning and direction before launching a nationwide public works program.

The New Deal in the South and West

The white and black workers in the South cannot be organized separately as the fingers on my hand. They must be organized altogether, as the fingers on my hand when they are doubled up in the form of a fist.…If they are organized separately they will not understand each other, and if they do not understand each other they will fight each other, and if they fight each other they will hate each other, and the employing class will profit from that condition.

—A. Phillip Randolph

The Roosevelt administration created several programs that were aimed at providing targeted relief within a particular region, but none was as ambitious as the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA)A regional New Deal agency that sought to bring low-cost electrical power to one of the most depressed areas of the country by constructing hydroelectric dams. The TVA also sponsored a number of infrastructure projects, as well as health and educational initiatives.. Inspired by the president’s emotional visit to an economically depressed region of the South, the TVA sought to provide direct employment through the construction of roads, buildings, bridges, and other projects. Most importantly, the TVA built hydroelectric dams to bring low-cost electricity to the area that would encourage commercial and industrial development. Many critics were understandably concerned about the environmental consequences of building dams all along the Tennessee River. In addition, many rural families who lived in the river valley were displaced in the process of construction. However, the TVA succeeded in spurring the growth of factories that brought modest prosperity to an area that had been among the most economically depressed regions of the country.

Figure 7.7

A family near Knoxville that was displaced by one of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) projects.

Not all residents of the Tennessee River Valley shared equally in the progress. Only 1 percent of TVA employees were black, and these individuals faced segregation while at work. Later New Deal public works programs such as the WPA would fare better, expanding from a workforce that was 6 percent black to one that was just over 13 percent. Few of these workers had any opportunities for advancement, as only eleven out of the 10,000 Southern WPA supervisors were African Americans. However, for the small number of black families who found work with the TVA, as well as the thousands of white families, the TVA was nothing short of a godsend. It was also a political boon for Roosevelt. Northern progressives hoped the government would launch similar projects around the country, while Southern conservatives cheered their president’s economic support for their region. The creation of the TVA represented the first federal support for development of the South outside of Virginia or the Atlantic Coast. After generations of opposing the growth of the federal government, Southerners welcomed federal intervention once it was directed at the development of their infrastructure and economy.

The TVA would prove enormously successful and was one of the most popular programs of the New Deal. Nevertheless, it would take many years for dams to generate electricity that would fuel an industrial revolution throughout the Tennessee River Valley. For those living in the Deep South who were still largely dependent on cotton, the TVA offered little assistance. The price of cotton declined to half of its 1920 price at the start of the Depression. For farmers and sharecroppers in the South, as well as the millions of farmers in the Great Plains and Far West, immediate relief was imperative.

One of Roosevelt’s first programs was the creation of a federal agency that provided refinancing for the millions of farm families who could no longer afford their mortgages. Roosevelt’s next challenge was to alter the fundamental problem that had led to the mortgage crisis—the rapidly declining prices for agricultural commodities. Roosevelt’s solution was the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA). This agency offered direct payments to farmers who agreed to reduce their production. For example, an Iowa farmer who grew corn on 200 acres would be offered an amount equal to the profit he might expect to receive on 50 acres if he simply agreed to plant only 150 acres the next year.

Because the AAA was not approved until May 1933, farmers had already planted their crops, so the AAA paid them to plow their crops. For millions of starving Americans, the federal government’s decision to pay farmers to destroy crops and slaughter millions of pigs was the cruelest irony. In fairness, the AAA quickly adjusted its tactics and purchased crops and meat which were distributed to needy families. However, the AAA’s payments proved devastating for those who worked the land but did not own it. Landowners were effectively being paid to evict tenants, sharecroppers, and other farm laborers whose labor was no longer needed as a result of reduced production.

The AAA resulted in an immediate stabilization of farm prices, an important goal considering that a third of the nation depended on farm prices for their livelihood. The Supreme Court declared a few provisions of the law that rendered the AAA unconstitutional, but this action merely led to relatively minor modifications in the way the AAA was funded and administrated. Although the AAA was favored by farmers and is generally considered a success, one of the leading reasons for the increase in farm prices was the result of an ecological disaster that reduced crop yields on 100 million acres of farmland.

Irrigation permitted farmers to develop nearly every acre of flat soil in the Southern Plains. An extended drought in the mid-1930s turned much of this topsoil to dust. The natural vegetation of the Southern Plains had deep root structures, which had secured the topsoil from erosion for centuries, even during similar times of drought. However, several decades of commercial farming had altered the ecological balance of the Plains in ways that left it vulnerable. Winds blew across the treeless prairies, taking the dusty topsoil with it and creating the ecological disaster known as the Dust BowlAn ecological catastrophe during the mid-1930s within the Southern Great Plains. The Dust Bowl featured windstorms that removed the topsoil of 100 million acres of farmland. This topsoil had largely turned to dust as a result of drought and erosion..

The crisis of the Dust Bowl was so severe for farmers and those in cities who depended on the business of farmers that one in six Oklahoma residents abandoned the state during the 1930s. About 800,000 farmers and others who were dependent upon the farming industry were displaced as these lands were no longer productive. Most of these individuals headed to the West due to rumors of available jobs in California. However, jobs were also scarce along the West Coast, and the arrival of new job seekers led to tensions between these predominantly white refugees and Asian and Hispanic farm workers. The new arrivals were derisively labeled as “Okies,” regardless of what state they had migrated from, while nonwhite Californians were derided as un-Americans, regardless of how long they or their families had lived in the area.

Figure 7.8

Montana’s Fort Peck Dam was a Public Works Administration project that created one of the largest man-made lakes in the world when it was completed in 1940.

These dams and aquifers also created the possibility of irrigation, which could open millions of acres of previously arid land to farming. Cautious that such a course of action would further depress farm prices and possibly recreate the environmental disaster of the Great Plains, government policy restricted the use of water for farming and ranching in some areas of the West. However, many of these restrictions were ignored or modified. Before long, federal projects were directed toward facilitating the growth of industry and cities in some regions of the West. The result was rapid growth of the urban West in the next few decades that would encourage the most significant population shift in US history since the Homestead Act of 1862.

As the Dust Bowl demonstrated, aridity continued to define the American West. However, some New Deal initiatives sought to alter the region’s ecology and transform the West through the creation of massive dams that would provide both electricity and water for certain areas. Much like the TVA, the New Deal of the West placed its hopes in commercial development through damming rivers. The federal government demonstrated the almost limitless possibilities of American labor and engineering by constructing the Boulder Dam, which was later renamed in honor of President Hoover. The Hoover Dam spanned the Colorado River and was instrumental to the urban growth of Las Vegas, Phoenix, and Southern California. Similar dams were built in Washington State and across the Sacramento River.

Diplomacy and the Good Neighbor Policy

The Great Depression bolstered isolationism within the United States and likely influenced the decision to withdraw troops from Haiti and Nicaragua in the early 1930s. Roosevelt put an end to the Platt Amendment’s provisions granting US sovereignty of Cuban affairs, with the exception of the US naval base at Guantanamo Bay. These changes signaled the beginning of Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor PolicyA policy aimed at improving relations with Latin American and Caribbean nations by removing US soldiers from these areas and demonstrating greater respect for the right of these nations to govern themselves. The policy was supported by Roosevelt, although many Latin American historians disagree about the sincerity of US commitment to nonintervention in Latin American affairs during the 1930s and beyond., which would mark a new age in US foreign policy in the Caribbean and Latin America.

In contrast to the frequent military interventions and economic imperialism that had typified the last few decades of America’s relations with the region, Roosevelt declared that no nation “has the right to intervene in the internal or external affairs” of their neighbors. Humanitarian concerns mixed with economic self-interest in forming Roosevelt’s new policy, as many Americans suspected that their tax money was being squandered abroad. Others believed that America’s foreign policy was aimed at exploiting the land and labor of Latin American nations when it should be used to fund projects that spurred development at home.

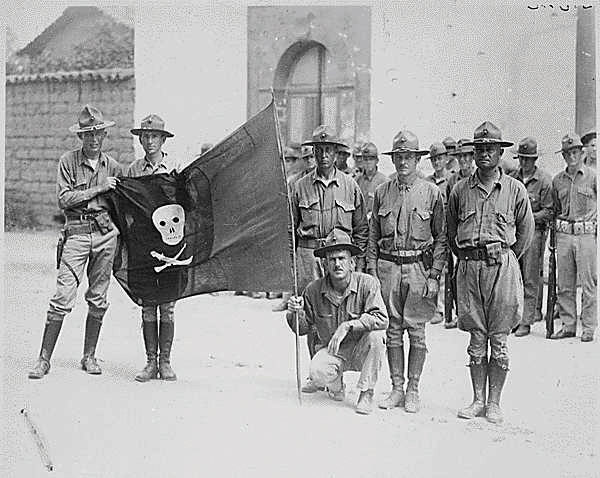

Figure 7.9

The United States Marine Corps in Nicaragua in 1932. Shortly after taking office, Roosevelt recalled these soldiers and many others deployed in Latin America as part of his “Good Neighbor Policy.”

Perceptions of self-interest likewise drove the decision to grant eventual independence to the Philippines, as long as the United States could maintain its naval bases in the region. The agreement granting Filipino independence also created a proviso that stripped Filipinos of the opportunity to work in the United States. This provision subjected any would-be migrants to the provisions of the 1924 National Origins Act, which placed quotas on the number of foreigners who could immigrate to the United States. Despite the fact that the Philippines would remain a US territory for another twelve years, by applying the terms of the 1924 law, only fifty Filipinos were permitted to enter the United States each year.

A different brand of isolationism led the Roosevelt administration to reconsider his earlier commitment to actively participate in the London Economic Conference of 1933. Partially as a result of non-US support, the conference failed to resolve international currency problems. Although it may be unfair to blame the Roosevelt administration for its unwillingness to actively devote itself to the stabilization of European currency, the rapid inflation of the 1920s and 1930s would contribute to the ease by which dictators seized power in central Europe. However, the Roosevelt administration would demonstrate great foresight in seeking to provide aid to England and the other nations willing to stand up to those dictators during his third term in office.

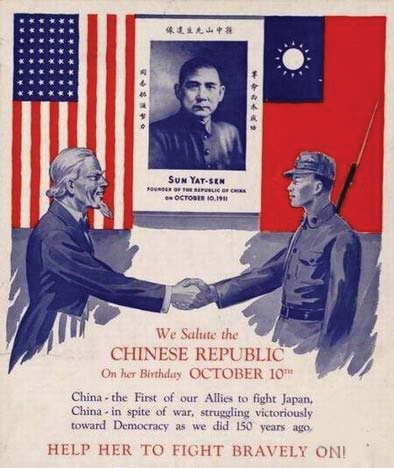

In the meantime, Roosevelt shocked many with his decision to open diplomatic and trade relations with the Soviet Union for the first time since the Russian Revolution of 1917. In addition to the desire to open US goods to new markets, Roosevelt hoped diplomacy would help to counter the growing menace of Japan and Germany. Humorist Will Rogers would comment that Roosevelt would have likely agreed to open diplomatic relations with the devil himself if only he would agree to purchase some American-made pitchforks. History would provide a kinder assessment, as Roosevelt’s overtures to the Soviets helped to thaw relations between the two leading nations in ways that would have a profound impact on the outcome of World War II.

Review and Critical Thinking

- How did Roosevelt stabilize the banking system? What were the positive and negative consequences of the federal government’s much more active role in the economy?

- Briefly summarize each of the major New Deal programs. In what ways were these programs related? Might any of these programs conflicted with other New Deal initiatives?

- In what ways did politics—both local and national—influence the direction of the New Deal?

- How did the New Deal seek to develop the West and South? What were the leading crises of these two regions, and how were they similar and different from one another? What was the long-term consequence of the New Deal for the South and the West?

- Roosevelt had once agreed with the internationalist perspective of fellow Democrat Woodrow Wilson, who had hoped the United States would take a leading role in the League of Nations. What might have led to the change of perspective a decade later?

- What was the Good Neighbor Policy? Do you think Roosevelt’s commitment to Latin American autonomy was influenced by a desire to reduce the cost of US commitments and investment overseas?

7.2 Last Hired, First Fired: Women and Minorities in the Great Depression

Learning Objectives

- Describe the challenges women faced during the Depression and the way that the New Deal affected women.

- Analyze the extent to which the Roosevelt administration provided a “new deal” for nonwhites. Identify the challenges for African Americans, Asian Americans, and Hispanics during the 1930s.

- Describe the way Native Americans were affected by the New Deal and the programs of the New Deal. Explain why some Native Americans might support the efforts of John Collier while others opposed him.

Kelly Miller, an African American sociologist at Howard University labeled the black worker during the Depression as “the surplus man.” African Americans were the first to be fired from jobs when the economy slowed, Miller argued, and they were the last to be hired once the economy recovered. Miller’s description was accurate not only for black Americans but also for women, Native Americans, Asian Americans, and Hispanics. For the first time, each of these groups had a voice in the White House. However, that voice was not the president. While Franklin Roosevelt focused his efforts on securing the electoral support of white Southerners and the cooperation of conservative Southern Democrats in Congress, Eleanor Roosevelt spoke for the “surplus” men and women.

Eleanor Roosevelt demonstrated her commitment to unpopular causes at the 1938 Southern Conference for Human Welfare in Birmingham, Alabama. The conference was an interracial coalition of Southern progressives founded the previous year. The group was dedicated to finding ways to provide greater economic opportunities for Southerners. Although they were not necessarily civil rights activists, for the first two days of the conference, members refused to abide by Birmingham law, which forbade interracial seating. When notified of the violation, police chief Bull Connor arrived and notified the participants that they would be arrested if they did not separate themselves into “white” and “colored” sections.

No woman has ever so comforted the distressed or so distressed the comfortable.

—Connecticut Congresswoman Clare Boothe Luce describing Eleanor Roosevelt.

Bull Connor would become notorious during the 1960s for his use of police dogs and other violent methods of attacking those who defied the city’s segregation ordinances. When Connor ordered the segregation of the 1938 meeting, the predominantly male audience rushed to comply. At that moment, Eleanor Roosevelt picked up her chair and sat in the aisle between the two sections, defying the segregationist police chief to arrest the First Lady of the United States. For this and dozens of other small acts of wit and courage, Eleanor Roosevelt was daily maligned by journalists who assaulted her character and integrity in gendered terms. Later interpretations of history would offer a different perspective on her character and integrity. While Eleanor Roosevelt adopted many of the conservative ideas about race and gender that typified those of her racial and economic background, she also challenged ideas about race, social class, and gender in ways that made her one of the most courageous and important Americans of her time.

Women and the New Deal

The New Deal reinforced existing gendered assumption about the family and paid labor. The Economy Act of 1933 established procedures requiring government agencies that were reducing their workforce to first establish which of their employees had spouses who already worked for the government and fire these employees first. Although the law made no mention of gender, it was understood that married women were the ones that were to be let go. A 1936 survey revealed that most Americans believed such measures to be fair given the scarcity of jobs for male breadwinners. When asked if married women whose husbands were employed full-time should work for wages, 82 percent said no.

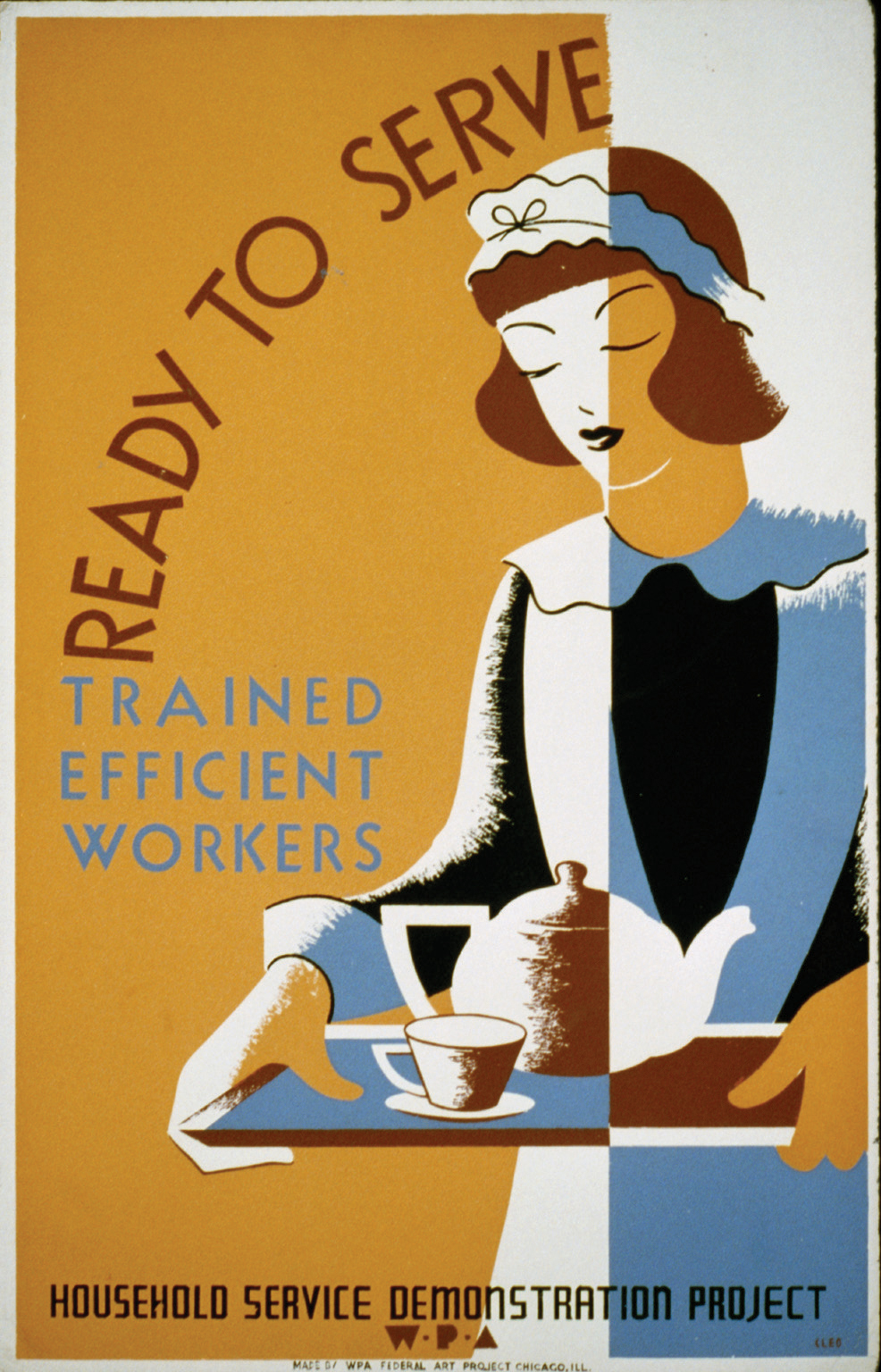

Figure 7.10

This WPA poster advertised the availability of maids who had completed training programs and were ready for domestic labor. Women were not encouraged to enter manufacturing fields as they would be during World War II due to the belief that doing so would take away a job from a male head of household.

The public also tended to approve of the practice of paying men higher wages for the same jobs. For example, male teachers were usually paid at least 40 percent more than women; in addition, principals and administrators were nearly always male. In fact, many times when a woman acted as the lead administrator in a school with all-female faculty, she was not listed as the principal, despite the clear expectation that she would perform these duties. In addition, married female teachers were often expected to quit their jobs—a traditional view that had eroded in recent decades but was revived as policy in some school districts during the Depression.

Single women without children might find work in schools but were often ineligible for other government jobs during the Depression. These gendered policies diverged significantly from programs such as the CCC, which employed millions of young men, and the jobs of the National Youth Administration, which were almost exclusively male. Women’s leaders such as Eleanor Roosevelt protested the inherent gender bias in these programs and were able to secure some work camps for nearly 10,000 young women.

Gendered notions of family and work made it especially difficult for women seeking jobs through the PWA, TVA, and the rest of the “alphabet soup” of federal programs. Only the WPA directed any specific action toward providing jobs for women, although these were usually in low-paying clerical and service positions. Even at its peak in 1938, only 13 percent of WPA workers were women. In addition, federal and state government policies encouraged private-sector employers to hire male heads of households first.

Those fortunate enough to find a job in the private sector found that the labor codes established by the NRA endorsed gender-specific pay scales that restricted women to certain kinds of jobs and still paid them less than men in many of those positions. The WPA itself did not permit explicit pay differentials, so men and women who worked the same jobs in WPA programs received the same pay. However, most women who worked for the WPA were relegated to low-paying clerical or “domestic” fields, such as preparing meals or sewing uniforms for male workers.

The Depression saw little advancement for the women’s movement. The pay differential between men and women working the same job remained at 60 percent, while the average salary for women was half that of men. The percentage of women in the paid workforce, which had steadily been rising, stalled at one in four workers. However, the number of careers open to women and the pay they received would expand in future decades, thanks to the number of women who joined the labor movement during the 1930s. The number of union women grew 300 percent during the decade as 800,000 women joined organizations such as the International Ladies Garment Workers’ Union.

Feminists also continued to advocate for legal equality for married women. Prior to the 1920s, American women surrendered their citizenship if they married a man who was not a US citizen. The same was not true for US men, who could become dual citizens if they went abroad, while marriage led to automatic citizenship for their wives and dependents who chose to come to the United States. In the 1920s, the Cable Act provided a way for married women to retain their American citizenship as long as their partners were at least eligible to become citizens—a provision that was partially directed at discouraging American women from marrying Asian immigrants. In 1931, women secured an amendment to the Cable Act that permitted women to retain their citizenship regardless of their husband’s status. Although the provision affected very few women, it was a symbolic victory and helped to further efforts of feminists who sought to protect the legal identity of married women.

A much more overt symbol of women’s advancement during the 1930s was the proliferation of women in leadership roles in government, women such as Frances Perkins and Mary McLeod Bethune. Perkins was raised in relative comfort and excelled in college with degrees in both the physical and social sciences. She chose to keep her name in marriage and was one of the first women to identify herself as a feminist during a meeting of women’s leaders in 1914.

Although Perkins also identified herself as a supporter of revolutionary change for women, she also believed that fundamental differences between men and women needed to be considered in the labor market. She favored laws specifically designed to protect women by limiting the maximum hours they might legally work, a perspective that put her at odds from many other feminists who supported the Equal Rights Act. Perkins is best known as the first woman to serve in the cabinet, and it is in that capacity that her legacy as a women’s rights activist remains. Perkins was the second longest-serving and perhaps the most influential member of Roosevelt’s cabinet, gaining the trust and support of labor and business leaders in the nearly exclusive male world of 1930s industry.

Figure 7.11

Mary McLeod Bethune emerged from poverty in South Carolina to become one of the most influential women in US history. She advised President Roosevelt on matters regarding race, led the National Council of Negro Women, and founded a college in Florida.

Roosevelt relied so heavily on the advice and support of Mary McLeod BethuneA leading educator and founder of Bethune-Cookman College, Bethune advised Roosevelt on matters of importance to African Americans and coordinated meetings of national black leaders known as the “Black Cabinet.” that he considered her the leading member of his “Black Cabinet,” an unofficial group of black leaders who advised the president on matters of race. The fifteenth of seventeen children of rice and cotton farmers in South Carolina, Bethune rose to become one of the premiere educators of the 1930s. The only school that was available to Bethune and her siblings in her youth was operated by a church several miles from her home. With the support of her family and neighbors, Bethune was able to attend this school. She quickly developed a love of books and an appreciation of education as the key to empowerment for her people.

In 1904, Bethune turned her home in Daytona, Florida, into a school for young black women. This school expanded into a teacher’s college and is today known as Bethune-Cookman College. Bethune also used her home as a headquarters for courses to prepare adults to pass the various exams that were required of African Americans who sought to register to vote. Despite physical threats by dozens of Klansmen, Bethune helped to register hundreds of black voters for the first time in South Florida. In 1935, Bethune founded the National Council of Negro Women and also served as President Roosevelt’s advisor on race relations. The following year, Roosevelt appointed her as Director of the Division of Negro Affairs of the National Youth Administration, making Bethune the first African American to head a federal agency.

During the 1930s, Bethune emerged as the most revered black educator since the death of Booker T. Washington. Like Washington, Bethune transformed a one-room school into a college. However, Bethune was far more assertive about her belief in black equality and even directly challenged Klansmen. Bethune also had experience leading schools from the Southern cotton fields to the Chicago slums. As her prestige increased, she traveled the nation as Washington once did, but did so in her own unique style. Not only was she known for her flair for fashion and her strong sense of racial pride, Bethune also refused to accommodate racial slights; her manner disarmed those who might be offended by a powerful black woman. When a white Southerner who was also a guest visiting the White House referred to her as Auntie—a carryover from the paternalism of slavery—Bethune smiled and inquired which of her many brothers and sisters were his father or mother.

A New Deal for Black America?

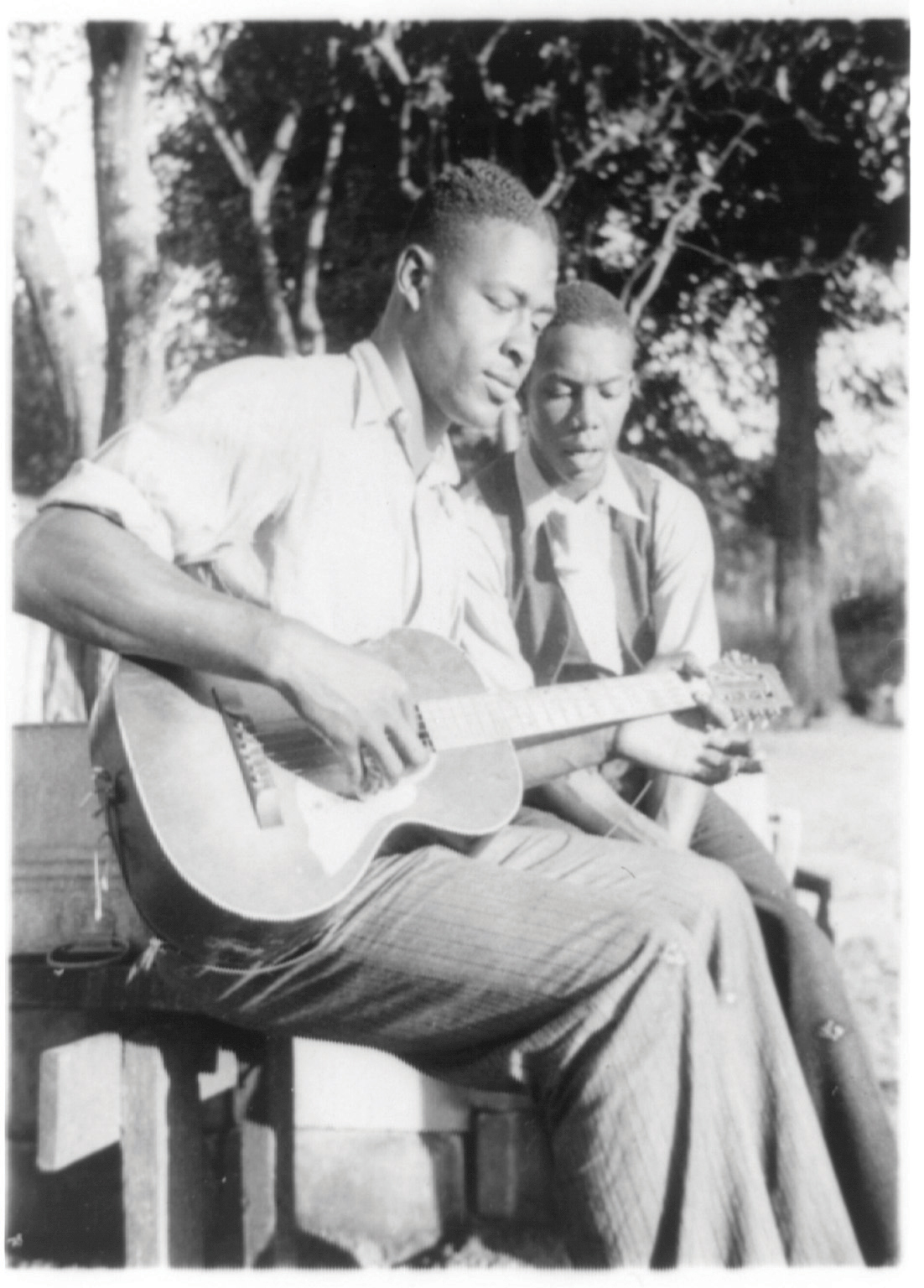

Figure 7.12

One of the WPA projects involved the documentation of folk music throughout the nation. This African American musician was photographed as part of this work, although few black musicians and artists were hired by the WPA directly.

The majority of black voters shifted their loyalty from the Republicans to the Democrats during the 1930s. The shift was both a reaction against the Republican Party and a result of Roosevelt’s tentative support for civil rights, which would become evident only during the crisis of war. In addition, various New Deal agencies offered limited job opportunities for African Americans. Roosevelt himself can best be described as both compassionate and paternalistic about the plight of black America. He met with but refused to be photographed next to black leaders until his second term in office due to concerns that even one photo with a black leader might alienate white voters. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs were usually progressive in terms of race in the North and West, but deferred to the views of white Southerners by permitting racial segregation while limiting the number and types of jobs available for Southern blacks. Eleanor Roosevelt would become an outspoken advocate for equal rights and a federal law against lynching. Although Roosevelt also supported these measures, he refused to back either even following his many landslide victories.

The panic of the Depression lifted the façade of racial fair-mindedness from the New South, as white workers cheered and pledged to boycott any business that employed black men beyond wages equal to whites. Some whites met with political leaders both within and beyond the South to try to create provisions requiring companies to only lay off white workers after first firing nonwhites. In Atlanta, a group of whites organized the “Black Shirts” in 1930 and marched with banners reading “No Jobs for Niggers until Every White Man Has a Job!” As a result, the Depression reversed decades of black economic progress and left 50 percent of black men unemployed at its peak.

In the wake of such catastrophe and economic hardship, the NAACP declined from 90,000 paid members following World War I to fewer than 20,000. Black leaders argued about whether to accept racial separatism; segregation, even if it is accommodationist, might be used as a tactical maneuver to win greater opportunities in the near-term for black workers. As a result, organizations like the NAACP were hardly able to mount a nationwide defense of civil rights and instead fought a rearguard action to protect black workers who were the first to be laid off when companies started downsizing due to the Depression.

The result of these campaigns and previous traditions of discrimination meant that even those few nonwhites who found work within New Deal agencies would receive only the lowliest jobs. Although many of the framers of the New Deal were progressive in terms of race, ethnicity, and gender, these agencies relied on the support of white political leaders. The New Deal’s primary goal was relief rather than reform, and each agency operated within a system that tolerated racial and gender discrimination.

Figure 7.13

This New York City WPA Poster offering classes to teach children how to swim depicts white and black children separately. The poster demonstrates the existence of informal segregation that was pervasive in the North.

Agencies such as the WPA determined pay by paying slightly less than prevailing wages as a means of preventing competition with private employers. The WPA also contained a provision that forbade the employment of anyone who had rejected an offer of private employment. Because the “prevailing wage” for Hispanic and African American women was often less than a fourth of what white men might be paid for manual labor, programs such as the WPA often denied employment to women and nonwhites who were seeking jobs beyond those that the discriminatory local market offered. That many New Deal agencies still offered better opportunities for employment should be viewed both as an indication of the progressive intent of many supervisors as well as a gauge of the opportunities for women and minorities within the private sector.

Many of the most progressive events of the 1930s demonstrated the limits of egalitarianism during the Great Depression. For example, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) finally accepted A. Philip Randolph’s union of black railroad porters in 1935. At the same time, the AFL refused to support measures that would have required the integration of workers within its various unions. With the exception of Randolph, the nation’s most prominent labor leaders also continued to at least unofficially support “white first” hiring policies. New Deal programs also discriminated against black families in subtle but significant ways.

For example, one of the main purposes of the newly created Federal Housing Administration was to provide federally guaranteed home loans for families who might not otherwise be eligible for home ownership. FHA loan applications did not inquire about an applicant’s race or ethnicity, which made it appear as though loan decisions were based only on other factors. However, the FHA’s underwriting manual indicated the belief that property values deteriorated when black families moved into neighborhoods. As a result, the FHA evaluated a loan based on the location of a house. Administrators consulted neighborhood maps that contained red lines around black neighborhoods and rated other ethnic clusters as credit risks. Because minorities could seldom obtain a house outside of a segregated neighborhood, even if they could pay cash, the FHA practice of “redliningIn this context, redlining is the process of designating entire neighborhoods as unacceptable credit risks based on their racial demographics. The term itself comes from the FHA maps, which designated minority neighborhoods with a red line. The FHA was created to assist homebuyers in need of credit and did not overtly make any distinction of race. However, the FHA refused to back loans in minority neighborhoods in an era of residential segregation, effectively denying credit to minority applicants.” minority neighborhoods effectively meant that the FHA would only support white families buying homes in white neighborhoods.

Despite the crushing discrimination in housing and employment, nothing demonstrated the persistence of racial inequality as starkly as the judicial system of the Deep South. Communist labor leader Angelo Herndon was arrested after leading a peaceful and biracial protest march in Atlanta. Although the participants had simply sought to draw attention to the plight of the unemployed, Herndon was arrested under an obscure statute permitting the death penalty for those leading an insurrection against the government. An African American graduate of Harvard law school defended Herndon and reduced his sentence to twenty years of hard labor on a Georgia chain gang. Many other black Communists found themselves in similar situations as federal and state authorities increased their attack against leftists once the Communist Party added racial equality as part of its agenda.

In neighboring Scottsboro, Alabama, nine adolescent black youths were arrested and charged with raping two white women on a freight train. The young men had jumped aboard a train in search of any work they could find when they found themselves in an altercation with a group of white boys in a similar situation. The white boys were outnumbered and thrown from the train, after which the white youths decided to “get even” by fabricating the charges of rape.

After eight of the young men were sentenced to death, some of the whites came forward and revealed the truth. However, two all-white Southern juries still recommended the death sentence in a series of mistrials and appeals that demonstrated the potential injustice of a white-only jury. A third trial included one black juror—the first to sit on a grand jury in Alabama since Reconstruction. However, under the laws at that time, an indictment could still be made with a two-thirds majority. The white-majority jury voted in favor of a guilty verdict and the death sentence.

Each of these lawsuits was funded by the NAACP, but the bulk of financial and legal support came from the Far Left. Communist organizations had taken the lead in financing civil rights cases and attempts to register black voters during the 1930s, and they likewise took the lead in defending the Scottsboro BoysNine African American boys aged twelve to nineteen who were accused of raping two white women on a freight train in Alabama in 1931. All but the youngest member of the group were sentenced to death in an infamously corrupt set of trials. The NAACP and the Communist Party provided legal defense, and one alleged victim and a witness both admitted that they had lied, yet the all-white juries kept returning guilty verdicts. Most of the young men spent years in prison until they were finally released.. Although the US Supreme Court twice ruled that these nine young men had been denied fair trials, it would take over a decade to secure the release of many of the defendants.

Latinos and Asian Americans

The Depression unleashed the hostility against Asian immigrants that was endemic in the 1924 National Origins Act and various state laws that limited the economic opportunities of Asian migrants in California, Oregon, and Washington. Much of this anger was directed at Filipino immigrants who were still legally permitted to enter the United States as citizens of an American colony. In October 1929, a mob of several hundred whites attacked a camp of Filipino laborers near Exeter, California. Angered by the decision of growers to employ Filipinos, the mob clubbed the workers and burned the makeshift homes where their families lived. An even larger anti-Asian race riot attacked a dance hall rented by Filipino workers near Santa Cruz in 1930, leading to hundreds of injuries. These attacks only escalated the violence against Asian workers, including several instances where sleeping quarters and community centers were dynamited. In addition, California amended its laws against interracial marriage to include a prohibition against “whites” marrying Filipinos in 1933.

Even those who were alarmed by the recent discrimination and violence tended to support the efforts of Western state legislatures who attempted to pass special laws barring Filipino migration. The federal government refused to approve these resolutions as long as the Philippines remained US territory. However, in 1934, Congress approved the Tydings-McDuffie ActIn response to Filipino activists, this 1934 law granted independence to the Philippines in 1944. Some believe that the law was inspired more by a desire to keep Filipinos from entering the United States, as the law also classified them as noncitizen aliens. Before the law, Filipinos were citizens of a US territory and legally permitted to live and work in the United States., which granted Filipino independence by 1944. Although the Philippines would still be a US territory until 1946, all Filipinos were immediately classified as noncitizen aliens and were unable to legally live or work in the United States. Although the law stopped short of requiring the immediate deportation of Filipinos already in the United States, Congress approved a measure in 1935 that encouraged voluntary repatriation. Many white Californians were even less subtle in expressing their encouragement that Filipinos return to their native lands. Anti-Filipino prejudice remained high until the United States required the assistance of the Philippines and Filipino-Americans in World War II.

The issue of barring Mexican immigration presented no such legal and diplomatic challenges, even though the Monroe Doctrine was often used to justify colonial practices toward Mexico and Latin America. State governments and federal officials conducted raids that led to the forced deportation of an estimated half a million Mexican Americans. Many of these individuals were placed in sealed boxcars and returned to Mexico in such an emaciated condition that the Mexican government was compelled to send millions of dollars in humanitarian aid to their northern border. Due to the nature of the mass arrests and deportation, many of those who were forcibly sent to Mexico were legal citizens born in the United States who simply lacked documentation at the time of their arrest. A high percentage of those deported were children who had most likely also been born in the United States.

Hostility against Mexican American laborers was not restricted to the Southwest. The 1930 US census was the first and only census that recorded Americans of Mexican descent as a separate race. Eugenicists attempted to use the façade of science to convince others of innate racial inferiority and backed a number of failed efforts to pass laws that would prevent anyone of Mexican descent from entering the United States. Given the high unemployment of white workers in the Midwest, the governor of Kansas wrote personal appeals to the six largest railroads in his state asking that they dismiss all Mexican laborers and hire whites in their place. Similar requests were made of railroads in neighboring Colorado, while farmers in Nebraska who continued to hire Mexican Americans were ostracized by their white neighbors.

Figure 7.14

The League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) was founded in 1929. This photo shows the first LULAC meeting in Corpus Christi, which brought various fraternal and civil rights organizations from around the Rio Grande Valley.

The 1930s also saw increased efforts by Mexican Americans to defend their civil rights. For example, college students of multiple races in Southern California joined a protest led by Mexican American students against Chaffey College. The administration had restricted Mexican Americans from using the college’s pool but soon agreed to end its policy of segregation. The activism of the students soon spread to the city of San Bernardino, who likewise ended its policies of segregation.

Protests against segregated schools also gained momentum in the 1930s. Ninety percent of Mexican American students in South Texas attended segregated schools during the Great Depression. The 1876 Constitution of Texas explicitly permitted separate schools for white and black children but was silent regarding other minorities. Despite the lack of specific legal guidance, white school officials had created a system where most Mexican American children were educated in separate schools taught by predominantly white teachers who spoke little or no Spanish. Mexican Americans in Del Rio challenged the separate and unequal facilities of their community in 1930.

The Del Rio movement was only possible because of a fundraising campaign that raised thousands of dollars from members of the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC)Created by the merger of several civil rights organizations, LULAC was formed in 1929 and remains the oldest and largest advocacy group for the rights of Hispanics in the United States.. LULAC chapters from McAllen and Harlingen north to San Angelo joined chapters of larger cities such as San Antonio in supporting the lawsuit. Although the Texas Supreme Court refused to hear Del Rio Independent School District v. Salvatierra, the lawsuit spurred the development of active LULAC chapters throughout Texas. The refusal of the Texas Supreme Court to hear the case may have been a tacit recognition that LULAC would win its appeal. Diplomatic agreements with Mexico and the US Census Bureau both required that people of Mexican descent be classified as citizens without any distinction of race.

The lawsuit and the refusal of state officials to address their concerns spurred a statewide movement challenging segregation. LULAC also worked with other organizations to form La Liga Pro-Defensa Escolar (the School Improvement League), which publicized the inferior conditions and unequal funding of separate schools. These campaigns were rewarded in 1948 when a federal court declared that the segregation of Mexican American children violated the Fourteenth Amendment. However, the court refused to consider whether the same conclusion would apply equally to African Americans who remained segregated under Texas law.

Native Americans