This is “Populism and Imperialism, 1890–1900”, chapter 3 from the book United States History, Volume 2 (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 3 Populism and Imperialism, 1890–1900

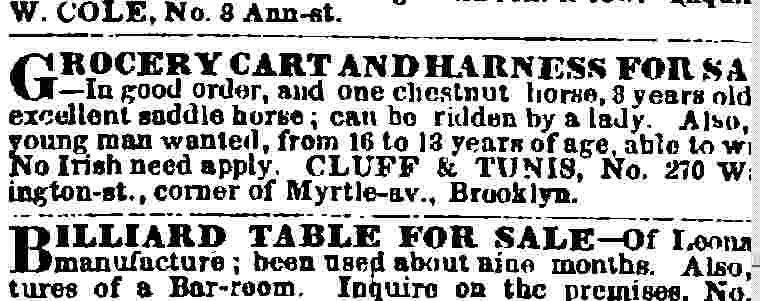

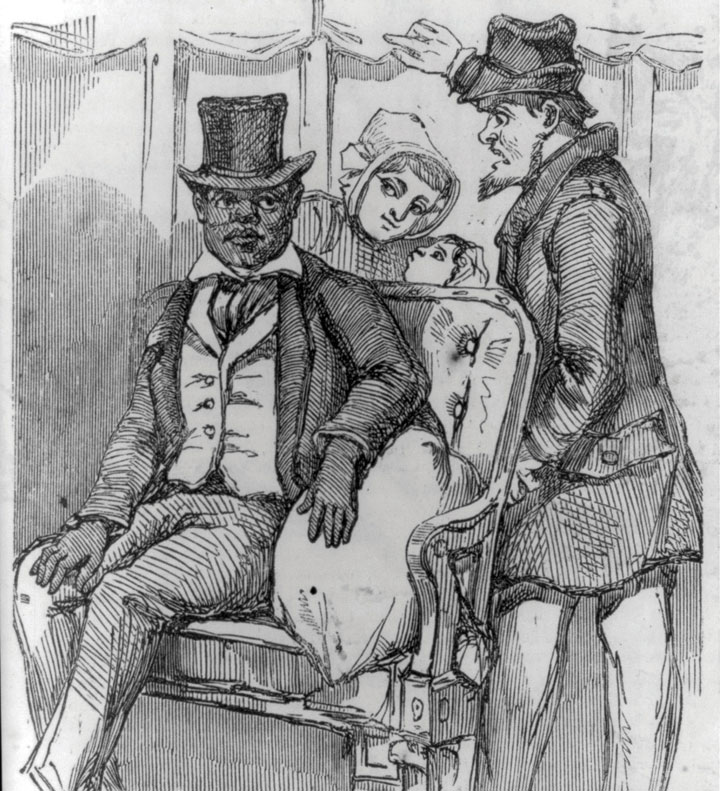

Four main developments occurred during the last decade of the nineteenth century. The first was the spectacular growth of cities. The transformation of urban America accelerated in the 1890s as port cities specializing in connecting the countryside with world markets gave way to the development of factories and financial centers throughout the nation. The second was the growth of a third-party movement known as Populism. Farmers and some urban workers united to form a class-based movement because they believed that their interests were not being met by the nation’s two political parties. Although the Populists would be a political force for only a brief moment, their ideas would greatly influence ideas about government and the nature of American politics. The third development was the growth of institutionalized racial discrimination. Segregation of white and black Americans moved from custom to law in the 1890s. This development illustrated a hardening of racial prejudice, but also demonstrated that black Americans were becoming wealthier and more assertive. Although segregation had existed in the past, by the 1890s Southern legislatures began passing ordinances that compelled racial separation by law. These laws were a response by racial conservatives who feared that black women and men were progressing in ways that might threaten the racial hierarchy. They were especially concerned that the new generation who had never known the “civilizing” effects of slavery must be compelled to keep “their place” at the bottom of Southern society.

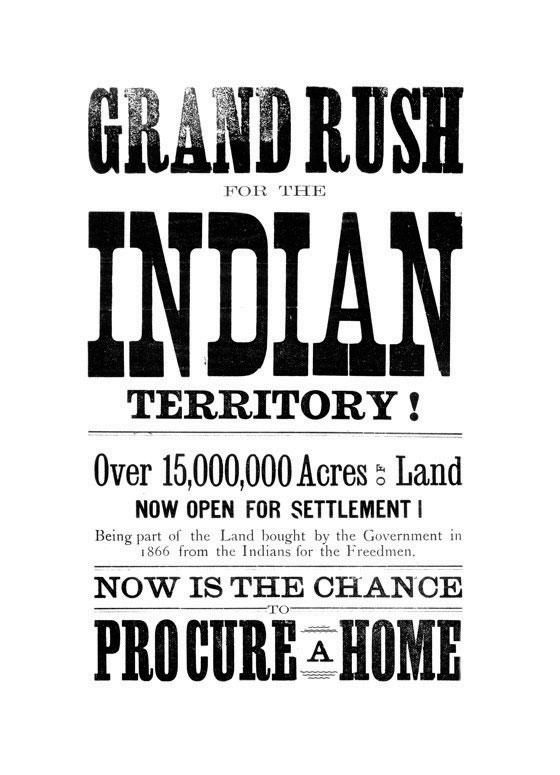

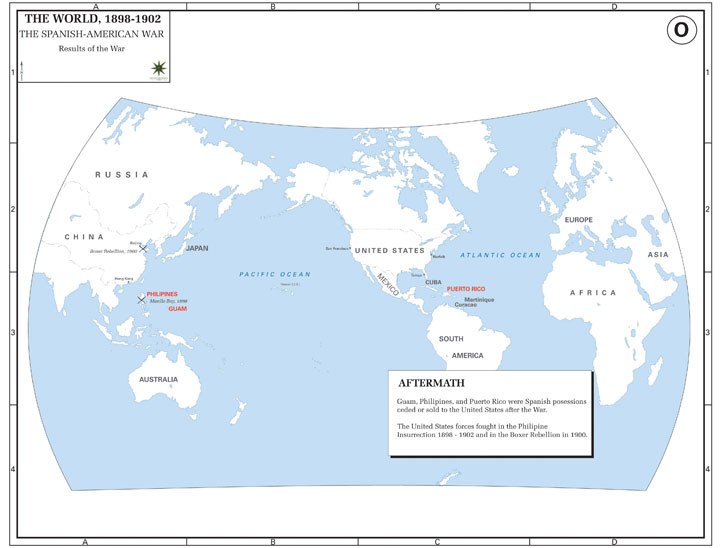

The fourth development was the physical growth of the nation and the acquisition of overseas territories. In 1800, the nation was a loose confederation of sixteen states with a total population of 5 million souls. By 1900, 75 million Americans belonged to a global empire that stretched across the continent and effectively controlled much of Alaska, Cuba, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Hawaii, and Guam. Ever aware of their own historic struggle against colonialism, American leaders claimed that they had no interest in creating an empire. The history of Western expansion demonstrated otherwise, even if few of the nation’s leaders considered the acquisition of land from Native Americans in these terms. In addition, Americans pointed out that the newly acquired islands in the Caribbean and Pacific had requested US assistance in their revolution against Spain. The United States promised that it was unique from all the other world powers. In some ways, America would live up to these promises by granting limited self-government to these areas or incorporating them into the nation and extending citizenship to inhabitants. When it came to the nonwhite peoples of the Caribbean and Pacific, however, the United States believed it could not grant full independence until the inhabitants proved that they were “ready” for democracy. In places like the Philippines, the inhabitants demonstrated an unwillingness to wait for self-government. Perceiving US troops as occupiers rather than liberators, Filipinos rose in armed rebellion. In other places, American imperialism was dominated more by a desire for commercial development and military bases. In these islands, inhabitants enjoyed a higher degree of autonomy even if their claims to national independence remained unfulfilled.

3.1 Urban American and Popular Culture

Learning Objectives

- Describe the factors that led to urban growth, and explain how US cities were able to accommodate so many new residents. Next, explain how immigration and migration from the countryside changed urban life.

- Explain why some Americans at this time were concerned about the growth of vice. Also, explain how the marketing of products developed at this time and how it changed US history.

- Describe the kinds of cultural activities that Americans enjoyed at the turn of the century. Discuss the reasons why activities such as sporting events became popular at this time. Finally, describe the growth of a uniquely American form of music called “ragtime” and the impact of popular culture on life in urban America.

The Growth of the City

The population of New York City quadrupled between the end of the Civil War and the start of World War I, as 4 million souls crowded into its various boroughs. Chicago exploded from about 100,000 to earn its nickname as the “Second City” with 2 million residents. Philadelphia nearly tripled in this same time period to 1.5 million. Before the start of the Second Industrial Revolution, even these leading cities served the needs of commerce and trade rather than industry. Early factories relied on waterpower, and the location of streams and falls dictated their location. By the 1880s, factories were powered by steam, allowing their construction near population centers. Soon the cityscape was dotted with smokestacks and skyscrapers and lined with elevated railroads.

The skyscraper was made possible by the invention of steel girders that bore the weight of buildings, which could be built beyond the limit of 10 to 12 stories that had typified simple brick buildings. Passenger and freight elevators were equally important. The price of constructing skyscrapers demonstrated the premium value of real estate in the city center. By 1904, Boston and New York completed underground railways that permitted these areas to expand—a marvel of engineering that required few modifications to the rapidly changing city. These early mass transit systems accommodated the proliferation of automobiles in the next two decades by removing trolley lines from the increasingly crowded streets.

These elevated and subterranean railroads (called the “el” or the “subway,” respectively) transported residents between urban spaces that were increasingly divided into separate districts. City planners mapped out districts for manufacturing, warehouses, finance, shopping, and even vice. Those who could afford it could purchase a home in the suburbs—outlying residential districts connected to the city by railways and roadways. Unlike the rest of the city, these neighborhoods were limited to single-family homes and included parks and even utilities such as plumbing and electricity. Suburbanites could also enjoy the pastoral trappings of America’s rural past with lawns and gardens. The daily commute seemed a small price to pay for the reduction of crime and pollution that was endemic within the city center. A suburbanite might even remain connected to the city through the proliferation of the telephone—still a luxury in the 1890s, but one that expanded to several million users within the next decade. However, the majority of urbanites were crowded into tenements that housed hundreds of people that might not include luxuries such as plumbing, ventilation, or more than one method of egress to escape a fire.

One in six Southerners lived in cities by 1900, and most blocks were occupied by either black or white families. The same phenomenon of residential segregation was still emerging in the North. In sharp contrast to the black population of the South, the majority of whom remained on farms and plantations, the vast majority of African Americans in the North lived in towns and cities. Both Northern and Southern cities contained one or more black-owned business districts. Most black communities with more than a few thousand black residents boasted their own newspaper, numerous doctors, a few attorneys, and a variety of stores and restaurants. Segregation encouraged the growth of these business districts where black shoppers were treated with dignity and at least a few black office clerks, professionals, and sales staff could find steady employment. Lingering prejudices and the desire to maintain language and culture sustained similar ethnic neighborhoods and business districts within Northern cities.

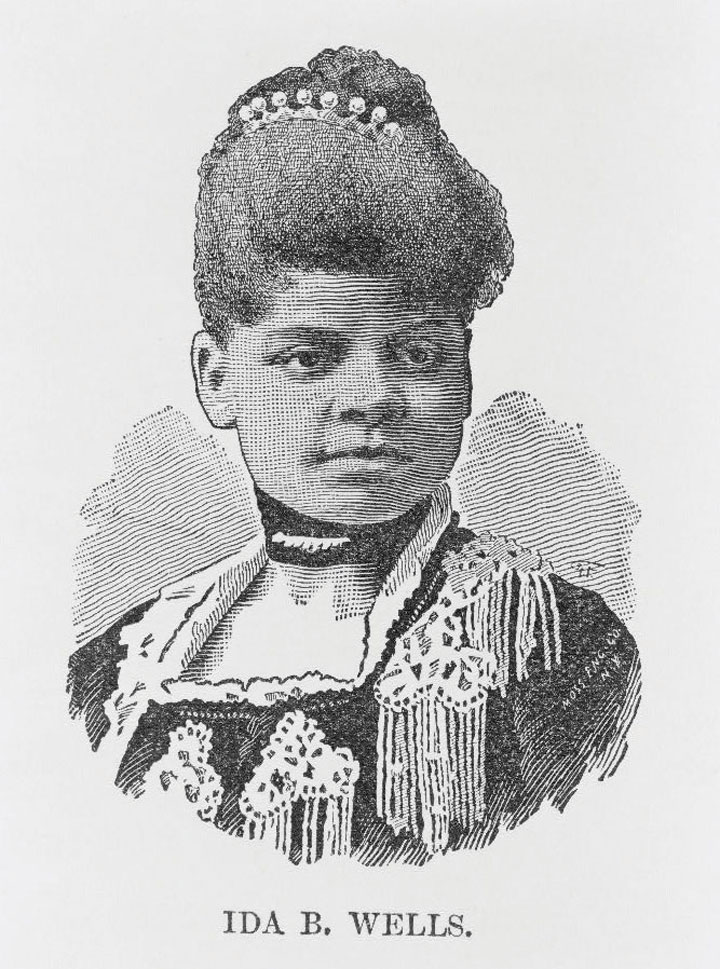

Figure 3.1

This 1902 photo shows continuing work being done to construct an underground rail system in New York City.

Swedes and Germans began to constitute the majority of residents in upper-Midwestern cities near the Great Lakes, and nearly every major city had at least a dozen newspapers that were printed in different languages. Although many Americans lumped immigrants together based on their language and nationality, immigrants sought association with those who were from the same region. In many parts of Europe, major cultural differences and old rivalries separated people who were countrymen only due to recent political realignments of Europe. As a result, dozens of fraternal and mutual-aid associations represented different groups of Germans, Italians, Poles, and Hungarians. Jewish residents likewise maintained their own organizations based on their culture and religion. As the migrants moved to smaller cities, Sicilians, Greeks, and northern and southern Italians might set aside old hostilities and see each other as potential allies in a strange land. Ethnic communities, such as San Francisco’s Chinatown and Baltimore’s Little Italy, might appear homogenous to outsiders. In reality these neighborhoods were actually melting pots where various people of Asian and Italian descent lived and worked.

The growth of cities was also the result of migration from the American countryside. In 1890, the US Census eliminated the category of “frontier”—a designator referring to areas with population densities below two people per square mile, excluding Native Americans. By this time, nearly every acre of fertile public land had already been sold or allotted. In response, historian Frederick Jackson Turner drafted a paper advancing an idea that would soon be labeled the Frontier ThesisAn idea proposed by historian Frederick Jackson Turner in 1890, which argued that the frontier shaped US history. Turner saw the frontier as “the meeting point between savagery and civilization.” At this westward-moving border, Turner believed that American society was constantly reinvented in ways that affected the East as well as the West.. Turner argued that the existence of the frontier gave America its distinctive egalitarian spirit while nurturing values of hard work and independence. For Turner, America’s distinctiveness was shaped by Western expansion across a vast frontier. At the frontier line itself, Turner argued, Americans were faced with primitive conditions, “the meeting point between savagery and civilization.” The result was a unique situation where the West was both a crucible where American character was forged and a safety valve for the overpopulation and overcivilization of Europe. Those who subscribed to Turner’s idea questioned how the elimination of the frontier might alter the direction of American history. Others recognized the congruity between Western expansion and urban and industrial life. Modern critics point out that Turner failed to recognize the agency and contributions of Native Americans and argued that his reliance on the mythic frontiersman also neglected the importance of families, communities, government, and commerce within the West.

Vice and the Growth of Urban Reform

To the frontier the American intellect owes its striking characteristics. That coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness…What the Mediterranean Sea was to the Greeks…the ever retreating frontier has been to the United States.…And now, four centuries from the discovery of America, at the end of a hundred years of life under the Constitution, the frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history.

—Historian Frederick Jackson Turner

Despite the “closing” of the western frontier in 1890, a new generation of Americans would see new frontiers throughout urban America. During the next three decades, these pioneers sought ways to improve sanitation and healthcare, provide safer conditions for workers and safer products for consumers, build better schools, or purge their governments of corruption. One of the leading urban reform projects was the attempt to eliminate certain criminal behaviors. Every major city and most small towns had their own vice districts where prostitution, gambling, and other illicit activities proliferated. These districts were usually restricted to one of the older and centrally located neighborhoods where upper- or middle-class families no longer resided. For this reason, vice was often tolerated by city authorities so long as it confined itself to these boundaries.

Vice was profitable for urban political machines that relied on bribes and the occasional fines they collected through raids. These limited attempts at enforcement filled city coffers and presented the impression of diligence. Police and the underworld often fashioned an unspoken understanding that vice would be tolerated in certain neighborhoods that were home to racial and ethnic minorities. A Jewish writer recalled playing on streets patrolled by prostitutes who advertised their services “like pushcart peddlers.” Innocence was an early casualty of a youth spent on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. “At five years I knew what it was they sold,” the writer explained. Children in multiethnic neighborhoods from Minneapolis to Mobile experienced similar scenes as the police “protected” brothels and gambling houses in exchange for bribes. In fact, most prostitution dens were located near police stations for this very reason.

Anne “Madame” Chambers of Kansas City provides a model example of the collusion between vice and law enforcement at this time. Chambers used the police to deliver invitations to her various “parties” to area businessmen. The police were also paid to guard the door of her brothel in order to protect the identity of her guests. Most clientele were not residents of the vice districts themselves but middle- and upper-class men who reveled in the illicit pleasures of Kansas City’s tenderloin district. Others engaged in the spectator sport of “slumming,” observing the degraded condition of inner-city life as a means of reveling in their own superior condition. Whether they partook in or merely observed the illicit pleasures of the red-light district, the physical separation of vice from their own quarantined neighborhoods provided both physical and ideological insulation from the iniquities of the city. A businessman could disconnect himself from the actions committed in the various tenderloin districts of his city and then return to his own tranquil neighborhood. Unlike the immigrant or the nonwhite who could not find housing outside of vice districts, the middle-class client retained the facade of respectability because of the space between his home and the vice district that quarantined deviance in poor and minority neighborhoods.

In many cases, a house of this type is a haven of last resort. The girls have been wronged by some man and cast out from home. It is either a place like this or the river for them…After a while they began to have hopes, and no girl who has hopes wants to stop in a place of this type forever, no matter how well it is run and how congenial the surroundings.

—Madame Chambers, reflecting on her life operating houses of prostitution in Kansas City between the 1870s and 1920s

These underworlds were host to both gay and straight. The legal and social fabric of the late nineteenth century equated homosexuality with deviance and therefore quarantined all public displays of homosexuality to the vice districts. Homosexuals at this time lived closeted lives outside of these spaces, although they described their own experience as living behind a mask rather than within a closet. In fact, historians have not found examples of the phrase “closet” in reference to gay life until the mid-twentieth century. Gay men and women of this era sought to create safe spaces where they could take off those masks. They created code words and signals such as “dropping hairpins”—a phrase referring to certain signals that only other homosexuals would recognize. To recognize and to be recognized by others permitted these men and women to “let their hair down”—another coded phrase referring to the ability to be one’s self. Because all homosexual behavior was considered illicit, gay men and women found the vice districts both a refuge and a reminder of the stigma they would face if they ever removed their mask anywhere else.

Although vice neither defined nor typified urban life, the police and political machines concentrated vice in ways that made it more noticeable while furthering America’s suspicion of urban spaces. Reformers hoped to do more than simply quarantine these establishments, pressing for tougher enforcement of existing laws while pushing for tougher prohibition measures against alcohol. The Progressive Era of the early twentieth century saw a unified effort to purge the city and all America of vice. In the meantime, a small group of reformers in the late nineteenth century believed that the best way to combat vice was to improve the condition of the urban poor. Most urban communities were already home to collective efforts to start daycares and educational outreach programs, long before the middle-class reformers took an interest in their plight. In many cases, churches provided partial financing for such institutions, while the women of a particular community volunteered their time watching children or teaching classes in English or various job-related skills. By the 1890s, middle- and upper-class women were increasingly involved in such efforts. Deriving their inspiration from European settlement houses that provided homes and/or social services such as daycare for working mothers, a host of American men and women brought the settlement house movement to America. The most famous of these was Jane AddamsA leader in the emerging field of social welfare, Addams observed settlement houses in London and used this knowledge to found Chicago’s Hull House in 1889. Addams also organized against child labor and was an outspoken opponent of the United State’s entry into World War I, an unpopular position at the time but one that led to her being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931..

Figure 3.2

Jane Addams was a pioneer of the settlement house movement in America, founding Hull House in Chicago. Addams was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931.

Addams was born into a wealthy family who viewed the purpose of college for women as a sort of literary finishing school that would prepare one’s daughter for marriage. They were shocked when their daughter returned from college expressing the desire to pursue an advanced degree, fearing that such a path would make it unlikely that their aging daughter would ever find a suitable husband. Undaunted, and refusing to abandon the development of her mind, Jane Addams studied medicine and the burgeoning field of social welfare. She toured the settlement houses of London and resolved to create similar institutions in the United States. In 1889, Addams secured and remodeled a mansion in Chicago called Hull House. Addams lived and worked at Hull House with her intimate friend Ellen Gates Starr and a variety of other women. Together, these women assisted poor mothers and recent immigrants who also resided at Hull House. Some of the social workers, such as Florence Kelley, were committed Socialists. However, most were short-time residents who came from wealthy backgrounds and were studying social work in college. Together, these college women and career reformers taught classes on domestic and vocational skills and operated a health clinic for women and a kindergarten for children. Before long, Hull House had become a community center for the largely Italian neighborhood it served. The Progressive Era of the early 1900s saw the expansion of the number of settlement houses, with approximately 400 similar institutions operating throughout the country.

Other settlement houses in Chicago and throughout the nation were directly affiliated with collegiate social work programs. This was especially true of historically black colleges such as Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (known as Hampton University today) in Virginia. Here, alumna Janie Porter Barrett founded the Locust Street Settlement House in 1890, the first of such homes for African Americans. Before this time, local organizations affiliated with the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC)Organized at a meeting held by Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin in Washington, DC, in 1896, the NACWC was formed as a national organization to promote and coordinate the activities of local African American women’s organizations throughout the nation. These activities included personal and community uplift as well as confronting segregation. took the initiative in providing social services within the black community. The NACWC was formed in 1896, but most of the local chapters predated the merger and had been active in creating orphanages, health clinics, schools, daycares, and homes for the elderly African Americans who were generally unwelcome in institutions operated by local and state governments. These women also created homes for black women attending predominantly white colleges throughout the North. For example, the Iowa Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs purchased a home where black students attending the University of Iowa and Iowa State University could live. They even discussed the merits of sponsoring special schools to help black women prepare for college. They soon abandoned this plan for fear it might be misunderstood by whites as an invitation to reestablish the state’s Jim Crow schools, which had been defeated by three state Supreme Court decisions in the 1860s and 1870s.

Figure 3.3

Activist, educator, writer, and leader, Mary Church Terrell was the first president of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs. She earned a master’s degree and taught at Ohio’s Wilberforce College, spoke multiple languages, and was a leader in the fight to desegregate the schools and the restaurants of Washington, DC, where she lived and worked for much of her life.

Mail-Order Houses and Marketing

Advances in transportation and communication created national markets for consumer products that had previously been too expensive to ship and impossible to market outside of a relatively small area. Companies such as the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company opened A&P retail outlets, while Philadelphia’s John Wanamaker pioneered the modern department store. Discounters like Woolworth’s offered mass-produced consumer goods at low prices at their “nickel and dime” stores. Department stores like Sears soon began marketing some of their smaller and more expensive items, such as watches and jewelry, through mail-order catalogs. By 1894, the Sears catalog had expanded to include items from various departments and declared itself the “Book of Bargains: A Money Saver for Everyone.” Isolated farmers and residents of towns not yet served by any department store suddenly had the same shopping options as those who lived in the largest cities. The Sears catalog and the advertisements of over a thousand other mail-order houses that emerged within the next decade shaped consumer expectations and fueled demand. By the early twentieth century, an Irish family in Montana might be gathered around the breakfast table eating the same Kellogg’s Corn Flakes as an African American family in Georgia. These and millions of other Americans could also read the same magazines and purchase items they had never known they needed until a mail-order catalog arrived at their doorstep.

Marketers recognized that they could manufacture demand just as their factories churned out products. Trading cards were distributed to children featuring certain products. Newspapers and magazines began making more money from advertising than from subscriptions. Modern marketing became a $100-million-per-year industry by the turn of the century, employing many of the brightest Americans producing nothing more than desire. The distribution of these advertisements extended beyond lines of race, region, and social class. Indeed, aspiration for material goods and the commercial marketplace that fueled this desire may have been the most democratic American institution. For some families, participation in the marketplace also became a reason to take on extra work. For others, the emergence of marketing was just another cruel reminder of their own poverty in a land of plenty.

Figure 3.4

Begun as a small circular offering watches and jewelry for sale by mail, the Sears Catalog quickly expanded to include hundreds of items. The catalog stimulated consumer desire, spurred by the advent of free rural mail delivery in 1896 and the company’s unique “money-back guarantee.” Years after its founding, a company employee predicted the catalog would become a primary source for historians by providing “a mirror of our times, recording…today’s desires, habits, customs, and mode of living.”

In addition to the retail outlets and mail-order houses, national brands emerged and offered products such as Coca-Cola, Crisco, and Quaker Oats. Traveling salesmen sold many products, from vacuum cleaners to life insurance and investments. The rapid growth of a national market for many of these products meant that many opportunities for miscommunication arose. Many companies simply hired more salesmen in hopes of turning their regional businesses into national empires. Rapid expansion meant that executives in distant home offices could do little more than issue guidelines they hoped their salesmen would follow. These individuals often established their own terms and prices that were designed to increase sales and their own profit margins. For example, salesmen of Captain Frederick Pabst’s beer figured out they could increase their own profit by adding water to the kegs of beer they sold. America’s taste for lighter beers was hardly a tragic consequence. For the family who invested all they had in watered-down stock or the widow who purchased a life insurance policy that did not offer the benefits she had been promised, such frauds held dire consequences. As a result, companies that delivered a consistent product and succeeded in protecting their brands from the potential avarice of their own sales staff developed national reputations. Before long, the reputation of such brand names became the most valued asset of a corporation.

Rise of Professional and College Sports

Like the corporations and mail-order houses that sprang forth during the late nineteenth century, spectator sports expanded from local contests organized around gambling during the antebellum period to become big business by the turn of the century. Boxing remained controversial in the 1890s, but it was also popular—extremely popular. The emergence of international icons such as the first true world heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan helped the sport to enter the mainstream of American culture. The son of Irish immigrants, Sullivan celebrated his heritage at a time when the Irish were heavily persecuted in America. Sullivan’s reputation for toughness was forged in the days of bare-knuckle brawls that ended only when one man yielded. These grueling fights were banned by the turn of the century, but stories of the Irish heavyweight champion’s grit lasted long after his first major defeat in 1892—an event that corresponded with Sullivan’s first use of boxing gloves. Although boxing moved toward respectability with the addition of gloves and rule-making associations, baseball retained its title as the most popular sport in America.

The Cincinnati Red Stockings became the first salaried team in 1869. By 1890, there were three major leagues, dozens of regional and semipro leagues, corporate sponsors, and crowds in excess of 10,000 spectators. The color line was drawn tightly in baseball, boxing, and other sports from the beginning, but it was never complete. Contrary to myth, Jackie Robinson was not the first African American to play in Major League Baseball. That honor belongs to Moses Fleetwood Walker, a catcher for the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American Association in 1884. At least one light-skinned individual of partial African heritage “passing” for white predated Walker, while dozens of players from Latin America who also had African ancestors played throughout the early twentieth century. One of the more elaborate demonstrations of the malleability of the color line occurred in 1901 when legendary Baltimore manager John McGraw signed Charlie Grant. Grant was a star of several African American teams who played in the barnstorming era of black baseball—the period before the formation of the Negro National League in 1920. An informal ban barred black players shortly after Moses Fleetwood Walker left Toledo because of the racism he endured. As a result, McGraw required Grant to adopt the name “Tokahoma” and pretend to be a Native American. The ruse did not last long, however, as Chicago’s emerging black neighborhoods within the city’s South Side gave such a friendly reception to Tokahoma that Chicago manager Charles Comiskey recognized the deception and refused to play the game if Charlie Grant took the field.

The greatest athlete at this time was likely a Native American who played professional baseball and football in addition to winning the decathlon in the 1912 Olympic Games. Jim Thorpe was born on Oklahoma’s Sac and Fox Reservation and was sent to a number of boarding schools. Like most athletes, he played semiprofessional baseball to help pay for his expenses and escape the military discipline and manual labor of the Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. This boarding school was designed to assimilate Native Americans into the dominant Anglo culture. Unfortunately, even though Thorpe needed to earn money to support himself while a student at Carlisle, the Olympic committee decided to enforce the ban against “professional” athletes on Thorpe. The Committee stripped Thorpe of his medals, despite the fact that many other Olympians had also played for money. During the 1980s, a campaign waged by historians and college students convinced the Olympic Organizing Committee to restore Thorpe’s medal posthumously.

Figure 3.5

Jim Thorpe was born on the Sac and Fox reservation in Oklahoma and is widely regarded as the greatest athlete in the history of sport.

Thorpe also led Carlisle to victory over most of the top college football programs in the nation. College football was second only in popularity to professional baseball at this time. College football rivalries were legendary by 1902 when Michigan defeated Stanford in the first Rose Bowl. Attendance at this game demonstrated that that the sport had progressed from the first college football matches of the 1870s that were informal challenges by student clubs who played by an ever-changing set of rules. By the 1890s, college football was the topic of conversation each weekend—among both enthusiasts and those who sought to ban the rough game. Early college football lived somewhere on the border between rugby and boxing, with little or no protective clothing. The introduction of the forward pass helped to spread the players across the field and reduced the number of crushed ribs at the bottom of the scrum. However, the rule change also added to the speed of the game, leading to concussions as players hit one another at full stride. In 1891, James Naismith, a physical education teacher in Springfield, Massachusetts, invented a new team sport that resulted in fewer injuries and could be played indoors during the cold winter months. He hung up two bushel baskets and had his students try to throw a soccer ball into the baskets. He would later coach college basketball at the University of Kansas.

The crowds at popular sporting events developed chants and songs to cheer along their team. The most famous song of all was “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” by a Tin Pan Alley composer. Colleges developed fight songs by taking popular melodies and adding their own lyrics or by altering popular fight songs such as “Oh Wisconsin” to include their own mascot and school. The University of Michigan’s fight song “The Victors” was also “borrowed” heavily by area rivals. The original lyrics celebrated the team as “Champions of the West”—an indication that the future Big Ten schools were still viewed as “Western” at the turn of the century.

While popular chants were often very similar from college to college, students and community members usually added elements of local flavor. For example, the chalk-rock limestone walls of the buildings that then formed the University of Kansas inspired students to change “Rah, rah, Jayhawk” into “Rock Chalk, Jayhawk.” Games with neighboring Missouri rekindled the historic feud where Southern bushwhackers killed antislavery leaders and burned the Free State Hotel of Lawrence. Missourians emphasized that the original Jayhawkers had also crossed into their state, usually liberating more whiskey and horses than slaves despite the historic memory of Lawrence as a Free State stronghold. Professional football failed to draw such community identity and remained on the margins until the mid-twentieth century. By 1900, college football was an institution, basketball was gaining popularity, and baseball in all its forms was the national pastime.

Popular Culture

The New York City neighborhood where the melodies of many of college fight songs and other tunes were written became known as Tin Pan Alley. The name may have derived from the “tinny” sound of the dozens of cheap upright pianos. Or it may be related to the cacophony of sound that resembled the reverberations of tin cans in a hollow alley as the neighborhood’s composers and sheet music publishers experimented with different sounds. From these alleys could be heard a new kind of music known as ragtimeA uniquely American form of music that featured “ragged” rhythms and a strong beat that compelled its listeners to dance or at least tap their feet. Its structure flouted conventional theories about music at the turn of the century. This genre inspired improvisation and gave birth to other forms of music such as jazz., a genre that blended black spirituals with Euro-American folk music. Made famous by urban composers, ragtime was born in the taboo world of red-light districts and interracial dance halls. In these hidden joints, white and black musicians created a uniquely Southern sound. Ragtime would soon spread to the black-owned halls of the North. Oral histories indicate that these melodies sounded just slightly off whenever whites imposed their presence on the early jazz halls of the upper Midwest. For all of its crushing oppression, ragtime was at home in the Deep South where black and white had always lived in intimate closeness to one another. The region’s language, food, and music reflected both the tensions and the bonds that forged generations of creole culture. A distinctly Southern form of expression, ragtime celebrated this fusion without apology and gave birth to the second uniquely American form of cultural expression—jazz music.

The most famous composer and performer of the era was Scott JoplinAn African American composer who was among the great innovators that created ragtime music. Joplin was born in Texas and traveled throughout the South, living and teaching music in Missouri and a host of other states as well as Northern cities such as Chicago., an African American who toured black communities from New Orleans to Chicago years before most of white America discovered ragtime. Thanks to the spread of new technologies, ragtime would be enjoyed in recorded form by many young white Americans, much to the chagrin of their parents. Within a few years, a growing number of white composers and artists added their talents to ragtime and joined traveling black musicians in spreading the new sound throughout the globe. Other white musicians, such as John Phillip Sousa, utilized the tempo of ragtime to create popular band music. Sousa specialized in stirring marches for military bands. The band director of the United States Marine Band, Sousa traveled the nation. Soon his “Stars and Stripes Forever” became one of the most beloved patriotic songs in America.

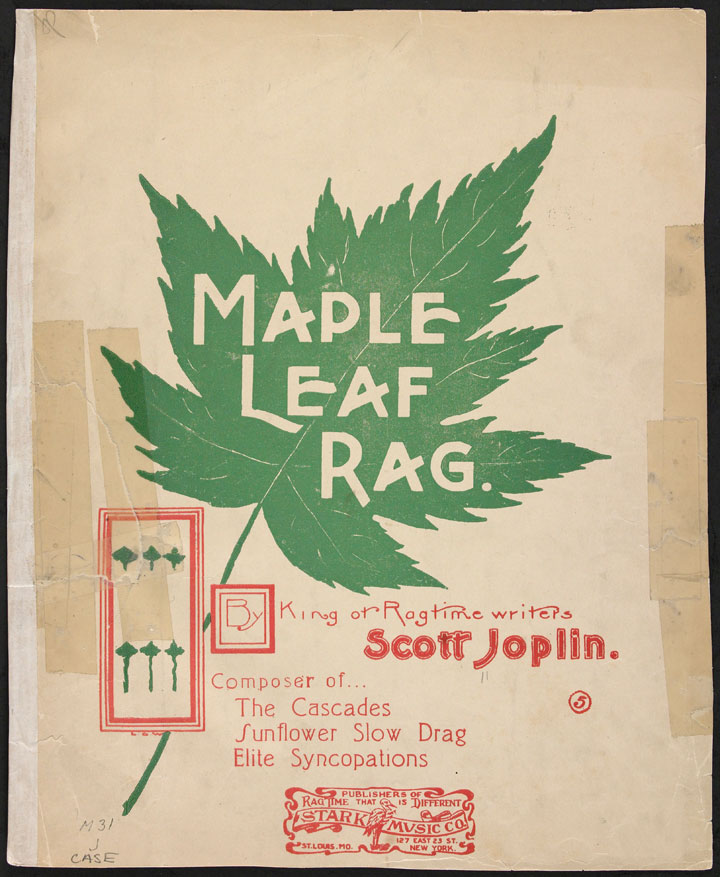

Figure 3.6

“Maple Leaf Rag” was Scott Joplin’s first successful composition. Joplin’s music was spread by the sale of sheet music and the popularity of this song led to the spread of ragtime as a uniquely American genre of music.

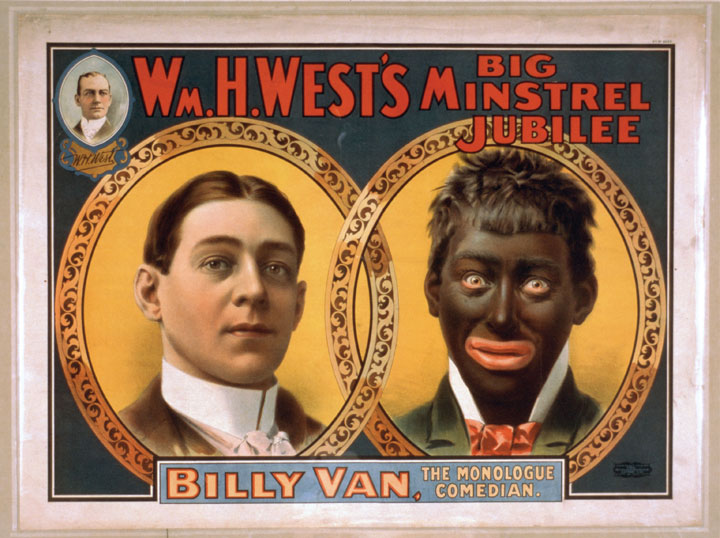

For those who preferred the theater, American audiences were treated to thousands of touring troupes who played several shows per day in every town large enough to draw an audience. The actors of these troupes had to be flexible, performing classical Shakespeare one afternoon and a vaudeville-type variety show a few hours later. The vaudevilleA type of variety show that became one of the most popular forms of entertainment at the turn of the century. A vaudeville show might feature sketch comedy, music, and burlesque dancers. show included songs, dance, slapstick comedy, and usually a chorus line of dancing women whose outfits left less to the imagination as the evening wore on. The more risqué, the better the chance a troupe would play to a full house each night. The exhortations of those who believed the theater to be the tool of the devil usually inspired more souls to attend these cabarets. The most popular form of entertainment at this time was the melodrama—an exaggerated style of morality play that demonstrated the persistence of Victorian standards of thought. The melodrama featured dastardly villains, damsels who constantly fell into distress, and daring men who never stooped to the antihero’s methods to save the day. An even larger-than-life type of live performance was the traveling circus. Most attendees of P. T. Barnum’s circus agreed that he delivered on his promise to provide audiences with the greatest show on earth.

Figure 3.7

Buffalo Bill poses with a group of Native Americans who performed in his touring shows that celebrated the “Winning of the West.”

Traveling circuses and vaudeville shows increasingly sought to present epic stories from US history. No topic was more popular that the fictionalized image of the West. As the last bands of Apaches and Lakota were annihilated or placed onto reservations, a sort of curious nostalgia emerged regarding what most assumed was a “vanishing race” of American Indians. The general public no longer vilified Native Americans once they no longer represented a perceived threat. However, few at this time attempted to understand Native American experience from their own perspectives. Ironically, a man with tremendous respect for native life and culture became the architect of a traveling exhibition that reduced the complexities of Western history into a cabaret. William Frederick “Buffalo BillWilliam “Buffalo Bill” Cody was a cowboy and scout for the military who also became a leading showman. Buffalo Bill’s traveling Wild West shows combined sentimental Western history with vaudeville entertainment that thrilled crowds around the globe.” Cody’s Wild West Show thrilled audiences with displays of horsemanship, sharpshooting, and other rodeo skills by cowboys and cowgirls. But the main attraction and the reason millions in Europe and the United States paid to attend Buffalo Bill’s show were the “Indian attacks” on peaceful settlers that brought out the cavalry. For most Americans, Buffalo Bill’s sanitized and simplified reconstruction of “How the West Was Won” substituted for the real history of the American West. Audiences cheered as the cavalry gallantly rounded up the “rogue” Indians in a display of showmanship where no one really got hurt.

Review and Critical Thinking

- How did the rapid growth of cities affect those who lived in the nation’s urban areas, as well as those that continued to live in small towns and the countryside?

- Describe life within the urban vice districts. Why were these places tolerated by authorities, and what can one learn about urban and social history from studying these kinds of places?

- How did women like Jane Addams and Janie Porter Barrett make their mark on urban history? How did their participation in the public sphere counter and/or demonstrate notions about a separate sphere of activity for women?

- How did marketing and the development of national brands and national markets affect American life?

- Many Americans at this time feared that the character of the nation was being degraded by a culture that placed too much value on material possessions. What kinds of evidence might they have cited to support this view?

- How did popular culture and entertainment reflect American society at this time in the nation’s history? What can one learn from analyzing cultural history?

3.2 National Politics and the Populist Party

Learning Objectives

- Explain how the Farmer’s Alliance spread and led to the development of the Populist Party. Identify the goals and issues of the Populists.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of the Populists in achieving their goals. Explain the obstacles they faced, such as race and the challenge of uniting urban workers and farmers. Finally, analyze how well the Populists were able to bridge these gaps.

- Summarize the issues and results of the election of 1896. Explain the fate of the Populists and their ideas and describe how the Populists affected the political history of the United States.

Rise of the Populist Party

During the 1880s, farmer’s collective organizations known as the Grange declined, as did the Greenback Party. However, the twin ideals of monetary reform and legislation beneficial to farmers were carried on by a new organization called the Farmers’ AllianceThe Farmer’s Alliance was a national federation of autonomous local farmer’s organizations that sought to represent the interests of their members. Even more than the National Grange, which preceded them, the Farmer’s Alliance had a heavy influence on politics between Reconstruction and the turn of the century.. The alliance was similar to the Grange, and in fact, some local chapters of the alliance had previously been affiliated with the Grange. The first alliance chapter was organized in Texas and quickly expanded to include over a hundred chapters by the early 1880s. The alliance had spread so rapidly due to its outreach/education program that contracted with traveling lecturers. These individuals earned commissions when they organized new alliance chapters. The alliance also affiliated with various existing farmer’s associations and formed partnerships with nearly a thousand local newspapers, most of which were already in print. By 1888, there were 1.5 million alliance members nationwide. This rapid growth was greatly facilitated by the decision of existing organizations to affiliate with the Farmers’ Alliance. For example, the Agricultural Wheel had been formed in Arkansas and attracted half a million members in other Southern states. In this way, the alliance was slightly different from the Grange. Its base of membership was local, and its chapters were autonomous. Perhaps more importantly, the alliance welcomed women over the age of sixteen as full members, as well as white tenant farmers and sharecroppers. The alliance would occasionally work with leaders of the Colored Farmers’ National AllianceDue to the exclusionary policies of the Farmer’s Alliance, black farmers formed the Colored Farmers’ National Alliance at a meeting in Texas during 1886. The organization grew quickly and had as many as a million members at its peak., an organization that grew to a million members and remained independent of white alliances.

Women were especially active in the alliance, a unique feature of the organization when considering the conservatism of the South and rural West. Despite ideas about separate spheres of activity for women and men, female alliance members chaired meetings, organized events, and delivered lectures. A significant number of women held key leadership positions in local and state offices within the alliance from the Deep South to California. Most strikingly, women were full members of most alliance chapters in an age when most women could only participate in “men’s” organizations as members of separate female auxiliary chapters. The efforts of female alliance members were usually phrased in conservative terms that stressed traditional roles of protecting the home and children. However, the entities the home needed protection from were banks and railroads. Participation in the alliance placed women in the public realm of political activity, circulating petitions and holding debates in support of new laws.

Because the Grange represented only landowners, their efforts had been largely dedicated to cooperative efforts to create stores, grain elevators, and mills. Alliance chapters engaged in these economic activities as well, and women operated dozens of the alliance cooperative stores. The alliance was even more active than the Grange had been in the political realm. Because its membership was more economically diverse, many of its chapters sought more radical reforms on behalf of poor farmers and landless tenant farmers. For the alliance, securing legislation protecting landowning farmers from the monopolistic practices of banks, commodities brokers, and railroads was only the beginning.

In 1887, the lobbying efforts of the nascent alliance, along with other farmers’ associations, led Congress to pass the Interstate Commerce ActA law demanded by farmers and passed in 1887 that required railroads to establish standard fares and publish these rates. This prevented the informal pricing practices that often discriminated against small farmers who had few options when it came time to ship their grain to the market.. The law required railroads to establish standard rates and publish these prices. It also prohibited railroads from giving free passes or other benefits to try and sway lawmakers and journalists from being favorable to railroad interests. The law also required that these rates be “reasonable and just” and created the Interstate Commerce Commission to regulate the business practices of railroads. These were seemingly commonsensical government reforms from the perspective of farmers, especially given the practices of some unscrupulous railroad operators. Prior to 1887, railroads could arbitrarily raise rates around harvest time or charge different rates to different customers to win the business of large firms. Small farmers had little chance of getting such discounts.

By 1890, a similar reform movement was being waged by small businesses and consumer advocates. These groups lobbied for the passage of the Sherman Anti-Trust ActA federal law passed in 1890 that gave the government the power to break up corporations that it believed were acting in restraint of free trade by forming monopolies or engaging in other practices that allowed firms to artificially raise prices., a law aimed at reducing the power of monopolies. Supporters of the new law believed that businesses, which should naturally be competing with one another, were often secretly working in concert to reduce competition by forming trusts. For example, the Beef Trust was an arrangement between the largest beef packers where members agreed not to bid against one another when purchasing livestock from individual farmers. If each leading purchaser of cattle refused to bid against one another, the price of cattle would be kept artificially low to the benefit of the beef packer and the detriment of the farmer. Dozens of trusts also maintained informal agreements against starting “price wars,” where each promised not to lower the price they charged consumers.

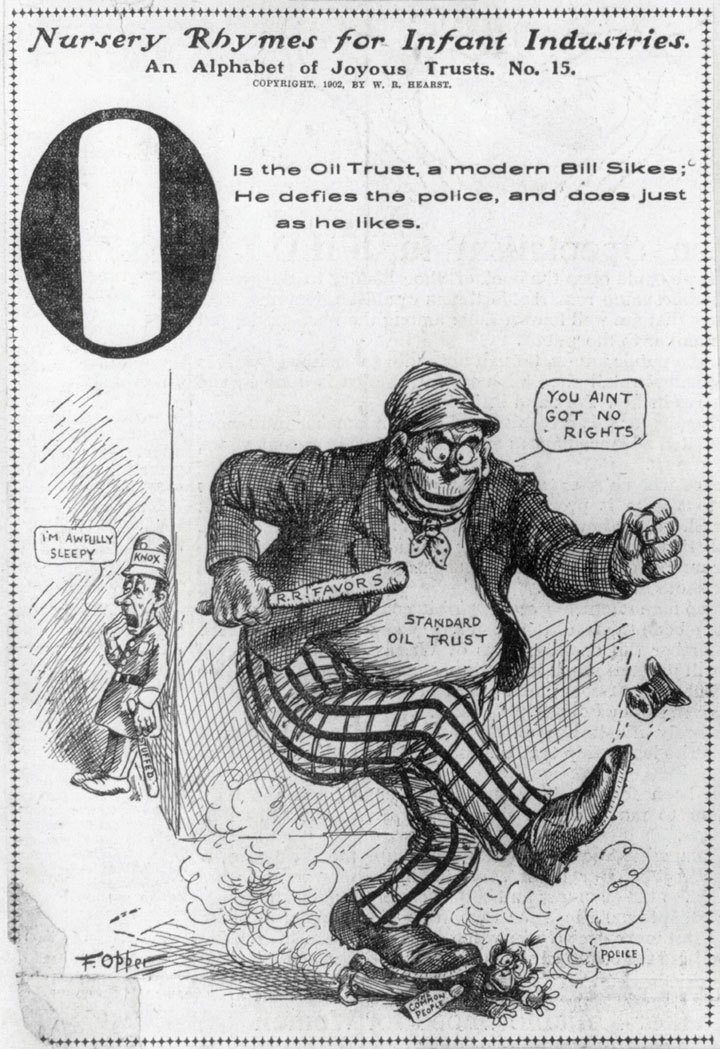

Figure 3.8

This satirical “nursery rhyme” depicts the oil trusts as a “modern Bill Sikes,” a reference to a fictional villain in Charles Dickens’s popular novel Oliver Twist.

Corporations defended themselves from their critics by pointing to the inefficiencies that occurred in the past when there were dozens of beef packers, oil refineries, and other competing businesses in every major city. In many cases, prices had declined when these companies merged or affiliated with the various trusts that controlled their industry. Although there was truth in these claims, there was equal validity to accusations of unfair business practices. The Sherman Anti-Trust Act gave the federal government unprecedented powers and empowered it to break up corporations that had formed “combinations in restraint of trade.” This vague phrase was intended to give wide-ranging power to those who sought to enforce the law and dissolve trusts. The new law was hailed as an end to monopoly; however, nearly all of the lawsuits brought under the terms of the law in the next fifteen years were dismissed on technicalities. In fact, corporations actually benefitted from the actions of courts during this time after the Supreme Court redefined the Fourteenth Amendment to defend the rights of corporations against the state.

From the perspective of farmers, the legal system was being commandeered by attorneys representing railroads and trusts. These entities were undermining both the Interstate Commerce Act and Sherman Anti-Trust Act, reformers believed, while the government stood idly by or actively assisted those who represented the trusts. Railroads continued to overcharge small farmers in violation of the Interstate Commerce Act, largely because the law required farmers to initiate a complaint. The understaffed regulatory commission could only investigate a small fraction of these complaints, and even when they believed they had a case they rarely had the resources to match their opposition. The same was true regarding anti-trust acts for ranchers who sold beef or grain to large corporations.

Figure 3.9

Alliance leaders met in Ocala, Florida, during December 1890. A number of local alliance chapters had already turned to political action by this time. For example, these alliance members in Columbus, Nebraska, formed their own political party and nominated a ticket of farmers for local and national office in July 1890.

Despite these frustrations, the partial victory of getting these laws passed and securing a handful of convictions also led to increased political activism among alliance members. In addition, the diminishing price of grain in the late 1880s led a number of farmers to view the alliance as a possible source of protection against economic decline. Alliance-sponsored lecturers continued to travel throughout the rural South and West during these lean years, touting the value of collective action. They also resurrected the ideas of rural Greenbackers and spoke against the gold standard and its tight money supply which kept interest rates high and farm prices low. Already influential in state and local politics in over a dozen states, the National Alliance turned to national politics. In 1890 they held a convention in Ocala, Florida. Their goal was to establish a platform that would unite alliance members from coast to coast. Equally important, alliance leaders sought political partnerships with labor unions and various middle-class reform movements representing the growing urban population. Delegates to the Ocala convention hoped their efforts would lay the groundwork for a new political party that would unite farmers and factory workers and represent the majority of working Americans. The degree to which they succeeded is still a subject of debate among historians.

The Subtreasury Plan and Free Silver

Delegates to the 1890 meeting drafted what became known as the Ocala Demands, a list of proposed changes to the nation’s political and financial system that challenged the conservative and laissez-faire policies of the era. The National Alliance dominated the Ocala meeting, and most alliance chapters endorsed the Ocala Demands and supported its vision of federal action on behalf of farmers. Chief among these reforms was a proposal to create federally subsidized warehouses where farmers could store their grain until they decided the market price was favorable. Many local alliance chapters had already tried to provide this service for their members, but most had failed in their objective because their members were in debt and could not afford to store their grain for more than a few weeks. Dubbed subtreasuries, alliance members believed these federal warehouses would solve their dilemma by issuing immediate payment of up to 80 percent of the crop’s present value. As a result, buyers would no longer be able to force cash-strapped farmers to sell their grain shortly after harvest. If all farmers participated in subtreasuries across the nation, the alliance argued, brokers and trusts could no longer dictate the price of grain.

The subtreasury planA proposal that was advocated by farmer’s organizations such as local Alliance chapters wherein the federal government would subsidize the construction of grain warehouses where farmers could store their grain in anticipation of better market prices. Farmers believed this would stabilize commodity prices and protect indebted farmers who often had no choice but to sell their grain as soon as it was harvested regardless of market conditions. demonstrated a revolution in sentiment among America’s farmers away from the concept of limited government that had typified Thomas Jefferson’s ideal of rural America. Instead of achieving freedom from government via laissez-faire policies and small government, the idea was now freedom through government via regulation and the subtreasury plan. In addition to this novel innovation, the Ocala Demands included a host of other ideas that had been proposed by both rural and urban reformers in the previous two decades. The delegates called for lower tariffs and greater regulation of railroads, although they stopped short of advocating direct government ownership of railroads. The platform also recommended the reinstatement of federal income taxes, which had been abandoned since the end of the Civil War. Although the wording of the resolution itself was nonspecific, alliance members intended that only the middle and upper classes would pay taxes, with the wealthiest paying higher rates. The Ocala Demands also supported the notion of governmental reform and direct democracy. The current practice at this time was for state legislators to appoint U. S. senators, but the Ocala Demands called for the direct election of US senators by popular vote. Relatively obscure in its own time, the Ocala convention and its demands would shape American political debate for the next decade.

The platform also supported a monetary policy that would soon be known as “free silverThe shorthand nickname given to the idea that the government should print money that was backed by both gold and silver. This would place more money into circulation, which would make it easier to obtain loans and provide a measure of relief for indebted farmers. Opponents believed that abandoning the gold standard would reduce foreign investment and destroy value of the dollar.”—an abbreviation of the phrase “the free coinage of silver.” This phrase simply meant that the US mint would create silver coins and/or print bills redeemable for silver and place them into circulation alongside the existing currency that was backed by gold. The word free simply meant “unlimited” in this context and was meant to differentiate their plan from the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890, which will be described later. Because currency was redeemable for a certain amount of gold, the government could only print an amount of money equal to the total value of gold reserves it controlled. While the population and the total amount of wealth increased each year, new discoveries and purchases of gold lagged behind. As a result, the strict application of the gold standard would mean that there would be such a small amount of currency in circulation that the laws of supply and demand would actually cause the dollar to increase in value each year.

Deflation caused the value of currency to increase over time. Although this sounds good in theory it can have disastrous effects on the growth of the economy. Deflation meant that those who wished to borrow money had to pay very high rates for two reasons. First, the relative amount of currency in circulation was shrinking, which meant borrowers faced stiff competition from other borrowers and lenders could practically name their terms. Secondly, because the value of currency increased each year, banks could also make money by simply hoarding their cash. This deflation of the currency was exactly what those with money wanted, and exactly what indebted farmers feared. For those who have more debt than currency, printing more money and causing inflation would actually bring a measure of relief.

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890 was intended to provide a small measure of that relief to farmers and others in debt. It required the government to purchase a limited amount of silver each month and then increase the amount of money in circulation by creating silver certificates that would be used just like the dollar. However, the plan did not work because consumers and investors preferred gold-backed currency. To make matters worse, the Silver Act financed the purchase of silver by issuing notes that could be redeemed in either silver or gold. Most holders of these notes immediately exchanged the notes for gold, which did nothing to increase the amount of money in circulation. Worse, these redemptions pushed US gold reserves dangerously low. The result was deflation, panic on Wall Street, and banks further restricting the amount of money they were willing to loan.

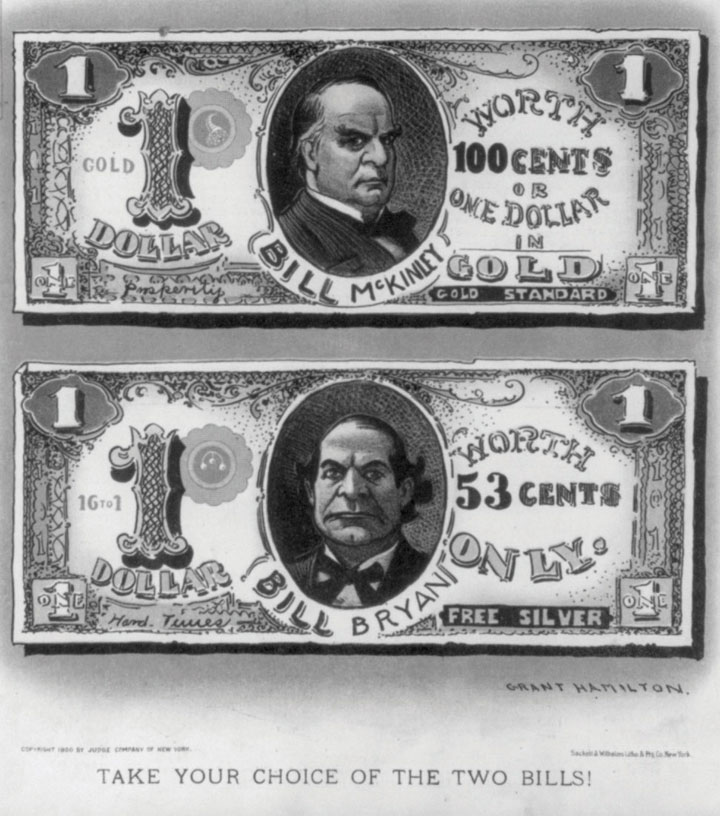

Figure 3.10

A political cartoon showing William Jennings Bryan who backed the idea of free silver on a one dollar bill. The bill bearing the image of his opponent William McKinley, a defender of the gold standard, is worth almost twice as much as Bryan’s money. The intended message was that the idea of free silver would cause economic instability. The slogans “We Want No Change” and “Four More Years of the Full Dinner Pail” were meant to support the status quo and the reelection of William McKinley.

Those who favored maintaining the gold standard cited the failure of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act as “proof” that increasing the idea of “free silver” was dangerous. In fairness, the Sherman Silver Purchase Act was not a fair test of the idea because it did not provide for the “free” (unlimited) coinage of silver. More importantly, the Sherman Silver Purchase Act did not treat silver-backed money as regular currency. The Ocala Demands sought to remedy this situation by having US currency backed by both gold and silver. It would create a flexible exchange rate that would eliminate any incentive for speculation or redeeming currency for one metal or the other. It also required the government to issue enough currency backed by silver that at least $50 per capita was in circulation at any given moment.

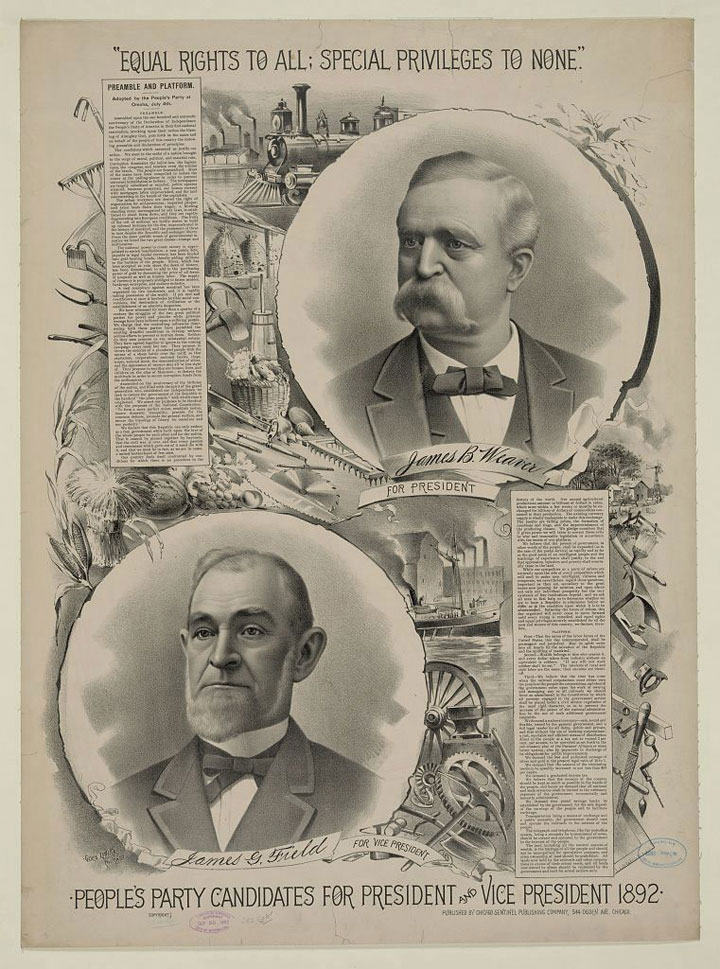

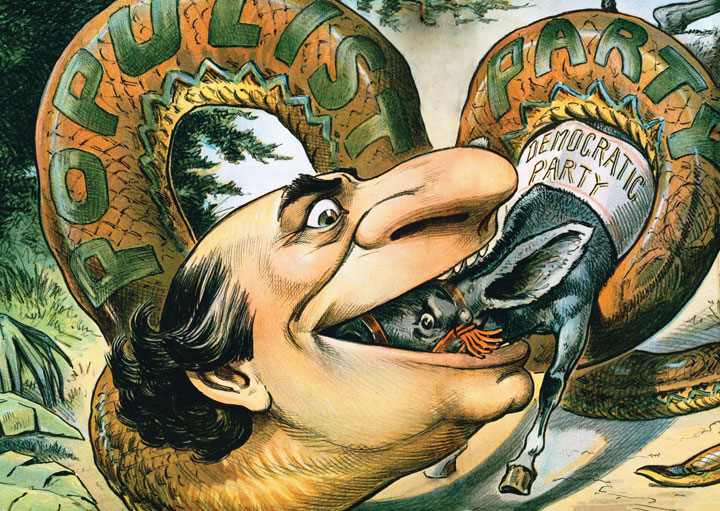

The alliance also formed partnerships with the Knights of Labor and especially laborers in mining and the railroad industry. Hoping to create a political party representing all productive laborers from the factories to fields, the Populist Party (known officially as the People’s Party) was formed after a series of conventions in 1892. National Farmer’s alliance president Leonidas L. Polk was nominated as the new party’s presidential candidate. Unfortunately, Polk died prior to the party’s national convention which was held in Omaha, Nebraska, in July 1892. Delegates at the Omaha convention nominated the former Greenback leader James B. Weaver in his place. Building on the ideas of the Ocala Demands, delegates created the Omaha PlatformThe formal statement of the policies of the People’s Party (also known as the Populists) that was issued at its formative meeting in Omaha, Nebraska, in July 1892.. This Populist statement of policy was drafted in hopes of uniting the demands of labor unions and the Farmer’s Alliance.

The Omaha Platform of 1892 may have been the most significant political document of the late nineteenth century, even though the Populist Party itself would dissolve within a decade. Although many of its specific regulations regarding economic and agricultural reform were not adopted, the ideas of the Omaha Platform would shape debate for years to come. In addition, many of its provisions would eventually become law. For example, the Omaha Platform called for immigration restriction (adopted in 1921 and 1924), the establishment of federal income tax (adopted in 1913 with the ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment), and the direct election of US senators (also adopted in 1913 with the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment). The platform also advocated more direct democracy by granting the people the power to submit laws through referendum and the ability to recall elected officials before their term ended. The Omaha Platform also advocated the eight-hour working day, term limits for politicians, use of secret ballots in all elections, and printing money that was not backed by gold. With the exception of government ownership of railroads and telegraph lines, nearly all of the major goals of the Populist were eventually adopted by law or custom.

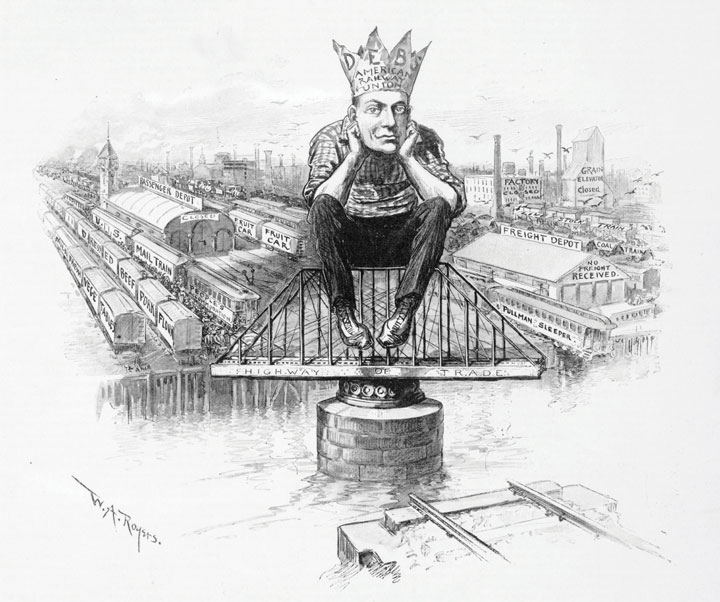

Figure 3.11

Populist candidate for president in 1892 James B. Weaver and vice presidential candidate James G. Field ran under the banner “Equal Rights to All, Special Privileges to None.” Field was a former Confederate general from Virginia while Weaver was a former abolitionist from Iowa. The two hoped to demonstrate national unity in an era of continued sectionalism in politics.

In the near term, however, the Populists struggled to attract supporters. Populists believed that the Republicans and Democrats both represented the money interest, a term referring to bankers and wealthy corporations who benefitted from the limited amount of currency in circulation. As a result, their platform advocated many of the ideas of the Greenback Party. However, most industrial workers were not in debt as farmers were. They feared inflation would increase prices faster than wages would rise. They also shared many of the same concerns of their employers and feared that altering the nation’s financial system could lead to instability and unemployment.

Figure 3.12

A photo showing armed men who enforced the declaration of a Republican victory in Kansas. A number of Populist leaders had seized control of the statehouse but the doors were broken and these deputized men regained control. Notice that this force included African Americans, who accounted for as many as 20 percent of Republican voters in southeastern Kansas and the state capital of Topeka.

Workers also tended to support tariffs on foreign imports because these taxes protected domestic production. Tariffs are taxes on imported goods. Without tariffs, overseas factories could sell their products in the United States for lower prices. Farmers tended to oppose tariffs because the nation was an exporter of cotton, grain, and other agricultural commodities. When the United States charged tariffs on foreign manufactured goods, other nations retaliated by imposing taxes on American exports. Farmers hoped reducing America’s tariffs would inspire other nations to do the same, reducing the taxes placed on American exports like cotton and grain. In short, farmers and workers may have shared similar experiences, but they often did not share identical financial interests. As a result, the Populist Party struggled to expand from an agrarian movement to one that united both farmers and urban laborers.

Populist presidential candidate James B. Weaver won over a million votes and carried Idaho, Nevada, Colorado, and Kansas in the 1892 election. The Populists also influenced the national election in 1892 when the Democratic candidate Grover Cleveland defeated incumbent Republican Benjamin Harrison—a reversal of the 1888 election in which Harrison had defeated Cleveland. The Republican and Democratic campaigns focused on issues such as the tariff. From the perspective of the Populists, this was only one of many issues and one that distracted from the more meaningful reforms they proposed. On a local level, Democrats and Republicans vied for control of Eastern cities and states, while the rising Populist Party secured numerous victories in the South and West. Populists even claimed victory in a majority of the districts of the Kansas state legislature. However, a three-day “war” between armed Populist and Republican politicians within the state capital led to arbitration and the Republicans ended up claiming a majority of the seats in the legislature.

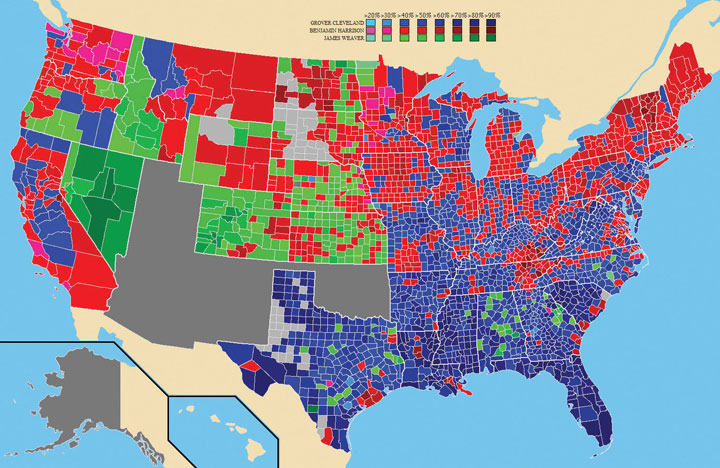

Figure 3.13

A map showing county-by-county results in the 1892 election. Notice the success of the Populists in the West and the pockets of support for the Populists in the otherwise solidly Democratic South.

The Populists were a growing political force beyond the West. After the 1892 election, Populists controlled a significant number of seats in state legislatures throughout the South as well as the western plains and mountain states. The party even sent 14 delegates to Congress, while a dozen states selected Populist governors for at least one term during the 1890s. The growth of the People’s Party also led to cooperative efforts between members of the two major parties and the Populists. Representatives of the Republicans and Democrats often nominated a single ticket composed of candidates from their party and a handful of Populists. This strategy of two political parties joining together to defeat the dominant party of a particular region became known as fusionIn this context, fusion was the strategy of merging two independent political parties under one ticket in order to increase the likelihood of winning elections.. In Western states such as Nebraska, where the Republican Party was dominant, Populists and Democrats often joined forces. Pockets of Republicanism managed to survive past Reconstruction in Southern states such as Tennessee, Virginia, and Texas, but the Democrats still dominated state politics. In these states, Populists and Republicans used the strategy of fusion to defeat a number of Democratic candidates. Fusion was most effective in North Carolina where black Republicans and white Populists created a fusion ticket and together swept the 1894 legislative and gubernatorial elections.

Race and Southern Populism

Despite continuing efforts to keep black voters from the polls, over 100,000 black voters cast ballots in each state of the Deep South in the early 1890s. As a result, white Southern Populist leaders from Texas to Virginia worked to mobilize black voters in ways that saw limited cooperation across the color line in politics for the first time since the end of Reconstruction. White Populist leaders agreed on the need to unite farmers and laborers, but they remained hesitant to embrace people of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds for fear of being labeled as “radicals.” This issue was especially problematic in the South. Although some Southern whites recognized that they shared common economic and political interests with African American farmers and sharecroppers, white alliance leaders rarely cooperated with black leaders. In most cases, the failure to cross racial lines proved the Achilles’s heel of Southern Populism. At other times, the economic interests of white and black farmers were not identical. For example, some white farmers owned land that was rented to black sharecroppers and tenant farmers.

Excluded from the Southern alliance, black Southerners established the Colored Farmers’ National Alliance in 1886. In 1891, a group of black cotton pickers around Memphis who were working on white-owned land organized a strike and demanded higher wages during the harvest season. Whites lynched fifteen leaders of this strike. The local white alliances were silent on the matter despite the fact that each of these men had been members of the Colored Farmers’ National Alliance. At other times, white and black farmers shared the same concerns. For example, a boycott against jute producers crossed the color line and spread from Texas to Georgia. Jute was used to produce the sacks that protected cotton bales. When an alliance of jute producers conspired to raise their prices, black and white alliance members throughout the South united and made their own bags from cotton until the “jute trust” backed down.

Historians have often been tempted to exaggerate the degree of cooperation between white Democrats and black Republicans in the South during the 1890s. Georgia’s white Populist leader Tom WatsonA leading Southern Populist, Tom Watson was an editor and Georgia politician who sought to unite poor white Southerners against the elite landowning families he believed still controlled the state through the Democratic Party. spoke forcibly against the methods some Democrats had used to intimidate and disfranchise black voters in the past. He and other white Georgia Populists even defended the life of a black politician from an armed white mob. However, Watson and nearly every other white Populist of the South were firmly committed to white supremacy and saw their partnership with black voters in tactical terms. They opposed the fraud and intimidation of black voters only when it was used against black men who supported the Populist Party. White Populists believed they were “educating” black voters by lecturing them about how voting for the Populist ticket would aid white farmers and landlords, providing benefits that would “trickle down” to black sharecroppers. If landlords could avoid paying high rates to railroads and men who controlled commodities markets, they argued, the landlords could then pay black tenants and sharecroppers higher wages.

From the perspective of black voters, Southern Populists were not much different from Southern Democrats who tolerated black suffrage so long as black voters agreed to vote as instructed. If the Populists spoke out against the knight-riding tactics that were similar to the Klan’s, it was largely because those tactics had favored Democrats in the past and were beginning to be used against white Populists. At the same time, the fact that some white Populists in the South sought a degree of cooperation with black political organizations made Southern Populists different from the Democratic Party. As a result, Southern black voters sought to maintain their independence and distance, but also sought tactical partnerships with white Populists.

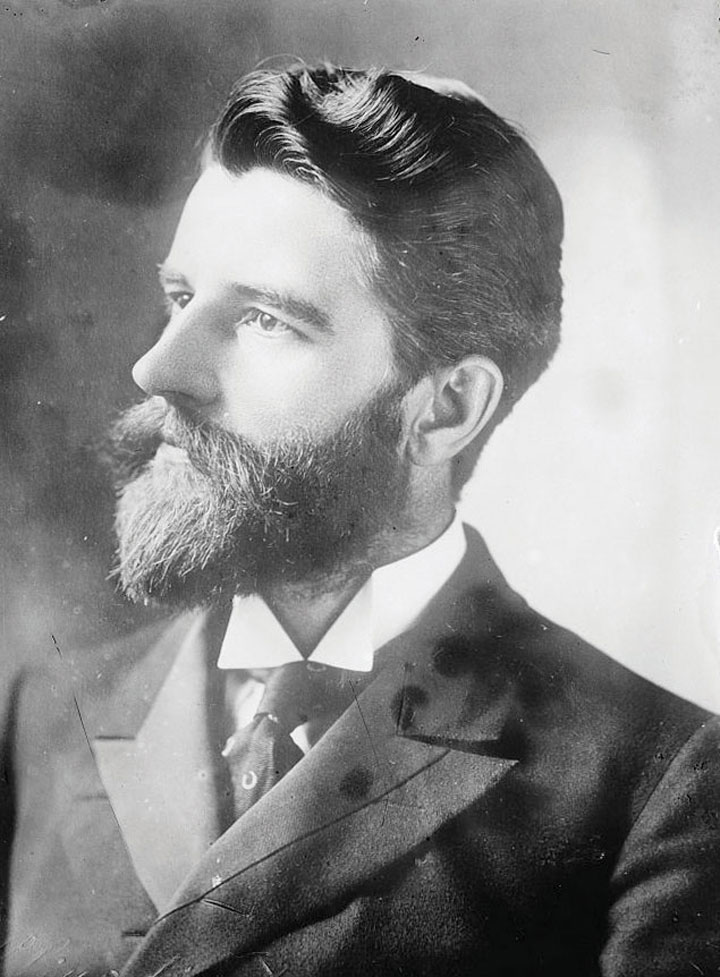

Figure 3.14 Marion Butler of North Carolina

North Carolina’s Marion Butler personified the racial tensions and tactics of white Populists. As a leader of his county chapter of the Southern alliance, Butler edited a Populist newspaper called the Caucasian. The masthead of Butler’s paper originally exclaimed “Pure Democracy and White Supremacy.” However, this was removed when the Populists decided they could advance their interests by courting black voters. Butler recognized that the only way to defeat the heavy majority enjoyed by the Democratic Party in North Carolina was to form a partnership with the Republican Party, even if it still contained many political leaders from the Reconstruction Era. Butler agreed to head a fusion ticket in 1894, including a number of white and black Republican leaders among white Populist candidates. Black Republicans and white Populists united behind the ticket, which swept the state. The Populist victory in North Carolina resulted in Butler’s election to the US Senate at the ripe old age of thirty-two. It also brought hundreds of local alliance leaders into the Populist-dominated state legislature. The Populist victory also resulted in George Henry White’s election to the US House of Representatives. White would be the last black Southerner to serve in Congress until the 1970s.

Progressive for its era and region, race relations in North Carolina would soon implode. The astounded Democrats launched an offensive against Butler and white Populists as traitors to their race. Ironically, Butler’s position as a defender of white supremacy should have been clear. Butler and the rest of the white Populist leaders were outspoken in their beliefs that black men and women were inherently inferior to whites. If Populists were different from Democrats in terms of race, Butler explained, it was because they were “not in favor of cheating and fraud” to exclude black voters. The Democrats shared no such reservations and branded Butler as a liberal who favored interracial marriage. They also created Red Shirt clubs that promised to redeem white women from the indignity of purchasing stamps from the handful of black postmasters the Populists had appointed.

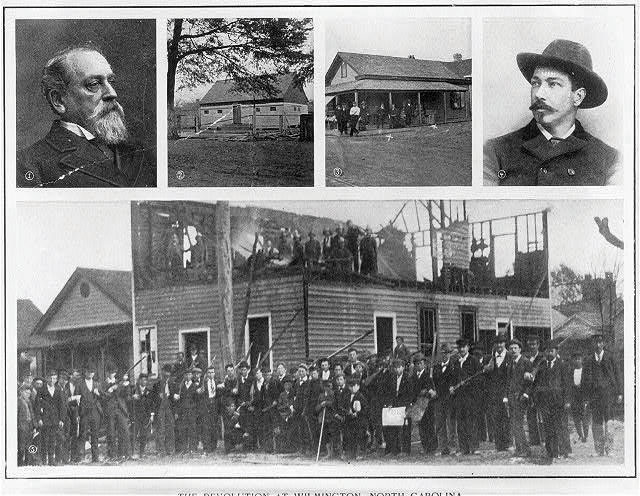

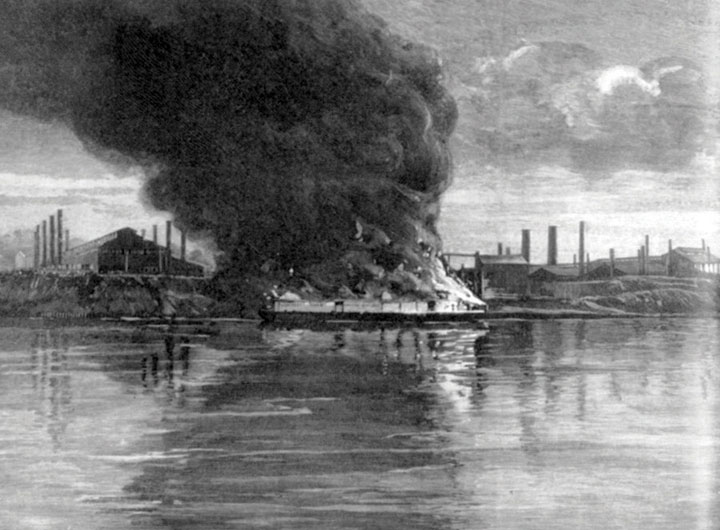

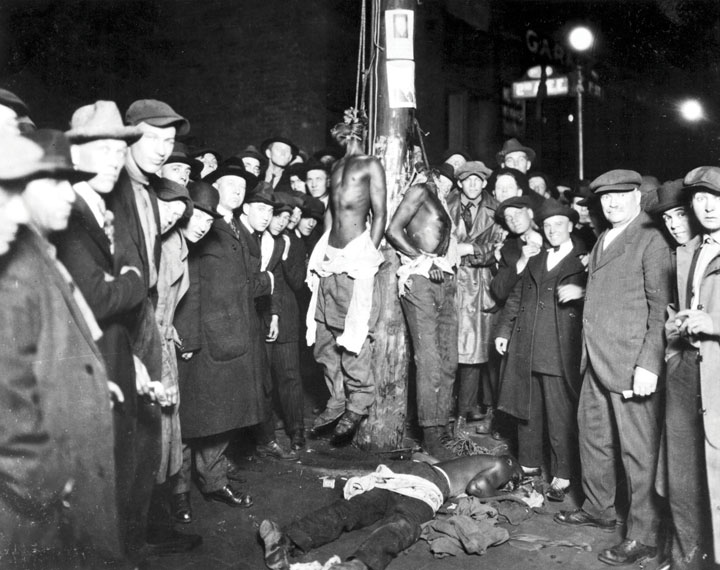

The Red Shirts then decided to use force to take control of the local government, much like what white mobs had done in Louisiana during Reconstruction. They destroyed the homes and businesses of black leaders and precipitated a massacre in Wilmington in November 1898. Officially known as the Wilmington Race RiotAn outbreak of violence against African Americans and black businesses in Wilmington, North Carolina, following the defeat of the Democratic Party in November 1898. Republicans and Populists had joined together to sweep the elections, but many of the victorious candidates were forced to give up their positions or simply fled the city for their lives., Red Shirts murdered a dozen black men, ransacked black communities, and burned the office of the African American newspaper the Wilmington Daily Record. The violence was anything but random, as Wilmington was the largest city in the state and contained a black majority that had just defeated the Democratic Party’s local candidates in the November election. Dedicated to controlling the entire state, white Democrats ran many of the few remaining Republican-Populist officials out of town and took control of the state legislature by force.

Only in the wake of such atrocity could North Carolina Populists be viewed as racial moderates. Populists were willing to give black voters a separate and subservient place in political and economic life. In return, they expected black voters to express their gratitude at the polls by supporting white candidates. In exchange for convincing men of their race to “vote properly,” a handful of black leaders might be appointed to minor offices. Black voters understood the limitations of their Populist “allies.” From the perspective of many black voters, however, fusion with the Populists could result in tactical gains such as funding for black schools and laws that might encourage fair treatment for sharecroppers.

Figure 3.15

The remains of the offices of the Wilmington Daily Record in the wake of the 1898 Wilmington Race Riot.

In the end, even this possibility for limited cooperation and tactical gains was derailed as North Carolina Democrats launched a malicious campaign. Black voters faced lynch mobs, the homes of black leaders were attacked, and white Populists were labeled Yankees and “lovers” of black women and men. Few white Populists were racial liberals, but these racial accusations were repeated with such frequency and intensity that truth became irrelevant. These accusations were also very effective. The Democrats swept the 1898 elections in North Carolina and enacted poll taxes that prevented all sharecroppers and tenants without access to cash from voting.

In 1900, North Carolina followed the pattern of establishing subjective literacy tests as a requirement for all voters. The tests empowered white registrars to disqualify black voters, regardless of their educational level. Given the recent campaigns against him, Butler phrased his opposition to the literacy test very carefully. Between various calls for white supremacy and his newfound desire to eliminate the menace of black suffrage, Butler meekly pointed out that literacy tests might unintentionally disfranchise hundreds of thousands of white voters. In response, the senator was subjected to death threats and labeled as a traitor to the white race. The Democratically controlled North Carolina legislature recognized that Butler’s argument was valid even as they excoriated him. They quietly responded by adopting a grandfather clause that effectively exempted whites from the literacy tests.

Populists in various other Southern states were likewise removed from office by many of the same methods. For example, Texas had been one of the leading states for Southern Populists until the adoption of the poll tax in 1902, a law that reduced the ability of poor farmers to vote. In 1923, Texas adopted a new technique to limit the effectiveness of black voters. The state created a system of primary elections in which only members of a particular party could vote. The direct primary was hailed as a progressive measure because it empowered the members of a party, rather than its leaders, to select their candidates. However, the Democratic Party restricted its membership to whites. Federal law did not permit such distinctions to be made in the general election, but the laws were silent regarding racial restrictions in private political organizations at this time. Even though black men could still legally vote in the general election, it mattered little because whoever won the Democratic nomination would easily defeat any candidate backed by minority voters or the nominal Republican Party of Texas. Black and Hispanic voters protested, but state and federal courts ruled that the Democratic Party could restrict membership however it chose. Attempts to declare the white-only primary a violation of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments failed until 1944.