This is “Appendix: An Example of the Hotelling Rule in Operation”, section 13.5 from the book Theory and Applications of Microeconomics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

13.5 Appendix: An Example of the Hotelling Rule in Operation

The Hotelling rule states that the nominal price of oil will increase at the nominal rate of interest. This seems a little bit mysterious. After all, we also think that the price of oil is determined by demand and supply in a market. In fact, these two approaches to the price of oil are completely consistent.

To see how, imagine that the worldwide demand curve for oil each year is as follows:

price = 1000 − 0.000001 × quantity,where we measure the price in dollars and the quantity in barrels. Individual suppliers are willing to sell oil at the price determined by the Hotelling rule. At higher prices, they will supply a lot of extra oil to the market; at lower prices, they supply no oil to the market. In other words, the supply of oil will be perfectly elastic at the market price.

But this is not enough to determine the market price. We know the market price this year only if we know the price next year. And we know the price next year only if we know the price the year after that, and so on. Unless we know the price at some future date, we cannot calculate the price today. But here is the trick: we do know that the price will eventually increase to the choke price (which is $1,000 per barrel in our example).

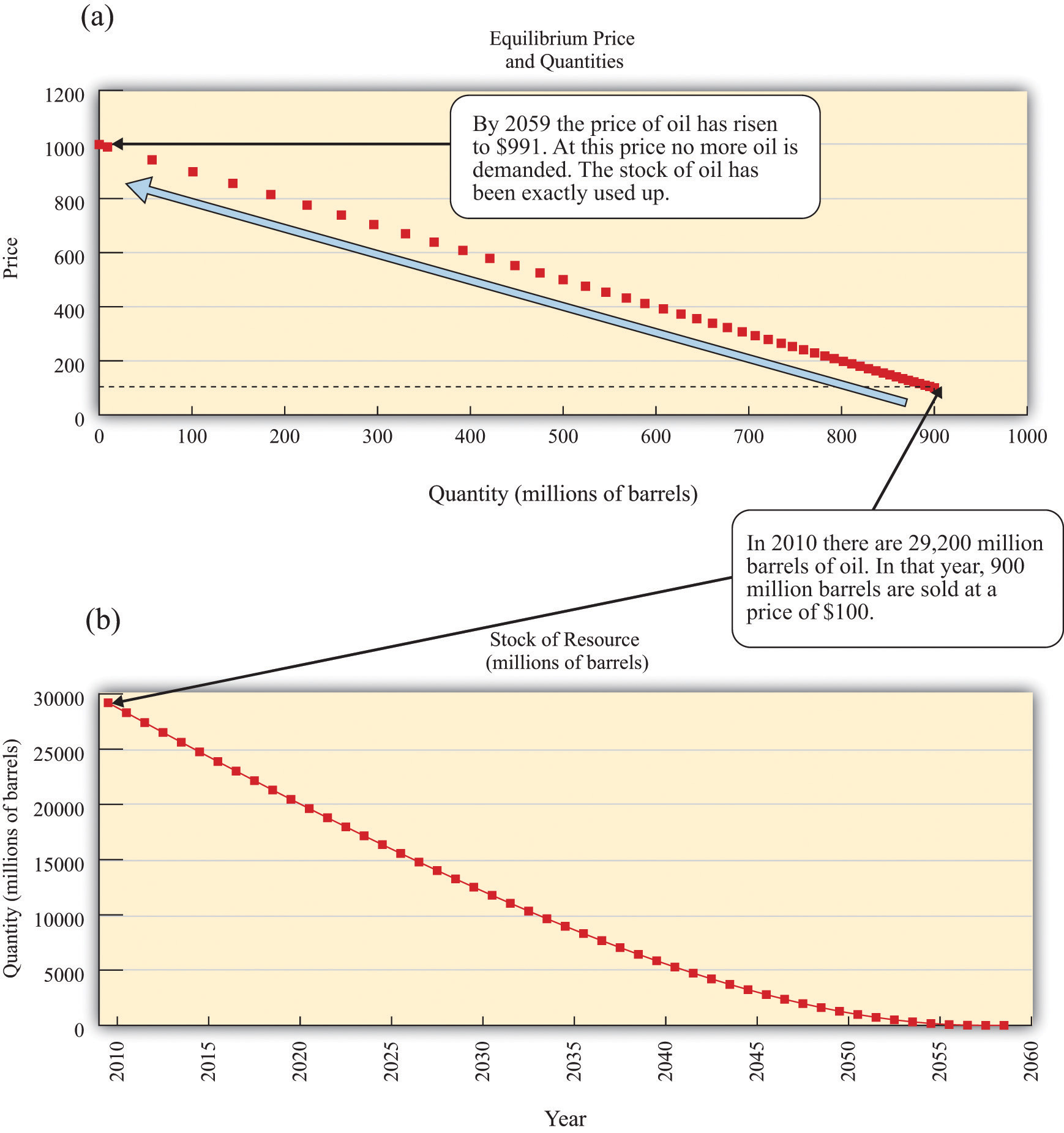

Over time, the price increases at the rate of interest, as implied by the Hotelling rule. If the demand curve is unchanged from year to year, the quantity demanded gets smaller. This makes sense: the increasing price reflects the increasing scarcity of the resource. The price increases until it eventually reaches the choke price, where the quantity demanded decreases to zero. But when will that happen? It has to happen when the last barrel of oil is being sold. If there is oil left over at that time, the price would decrease below the choke price. And if we ran out of oil before then, the price would have to hit the choke price earlier. Anything else would cause a mismatch between demand and supply. Thus the price today needs to be just right so that when the last barrel of oil is being sold, the price increases to exactly the choke price.

Figure 13.6 "An Example of Oil Depletion According to the Hotelling Rule" shows an example based on this demand curve. Suppose that the total amount of oil available in the world at the end of 2010 is 29.2 billion barrels, which is owned by many competitive suppliers. How will this oil get released to the market? In 2011, 900 million barrels of oil are sold, so the market price is therefore $100. The price then increases at the rate of interest, which is 5 percent per year in our example. By the year 2044, less than 4 billion barrels remain, and the price of oil has increased to $500 per barrel. In this particular illustration, we run out of oil in slightly under half a century: the last 9 million barrels of oil are sold in the year 2058, at $991 per barrel.

Figure 13.6 An Example of Oil Depletion According to the Hotelling Rule

These figures show an example of resource depletion according to the Hotelling rule. (a) The price and quantity of oil traded each year trace out the demand curve. (b) The stock of oil over time represents the supply curve. Initially, there are slightly under 30 billion barrels of oil available. In the first year, 90 million barrels of oil are sold in the market, at $10 per barrel. The price then increases at the rate of interest. In the year when the price reaches the choke price (2059), the stock of the resource is fully used up.