This is “eBay”, section 5.2 from the book Theory and Applications of Microeconomics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

5.2 eBay

Learning Objectives

- What are the economics of an eBay auction?

- How should I bid on eBay?

- How are gains to trade determined and shared when there are multiple buyers?

- What is the winner’s curse?

So far we have supposed that there is only a single buyer and a single seller. If you are thinking about selling a good on craigslist, however, there are many potential buyers of your good. In addition, you probably don’t know very much about the valuations of the different buyers. You might then like to find some way to make your buyers compete with each other. In other words, you might consider auctioning off the good instead.

You have probably at least visited the eBay site, and you may even have bought or sold an item on eBay. If so, you know it can be a convenient and efficient way to buy and sell goods. But what exactly is eBay? We answer this question by looking at the site from the perspective of participants. First we review how eBay works and look at it from the point of view of both a buyer and a seller. Then we bring some economic analysis to bear to better understand what is taking place on eBay and in other auctions.

Buying on eBay

Suppose you want to purchase something, such as a leather jacket, some cycling gloves, or a cell phone; the list of things that might interest you is endless. On the eBay page, you can search for the exact item you want to buy. Your search must be specific: if you search for “cell phone,” you will find thousands of products. You need to know the exact model of phone you want, and even then you may find multiple items for sale.

Auctions on eBay have several characteristics, including the identity of the seller, the time limit on the auction, the acceptable means of payment, the means of delivery, and the reserve price.

- Seller identity. Unlike when you purchase from a store, you do not get to see the seller on eBay, and you cannot simply walk away with the good. This may concern you. After all, how do you know the seller will actually ship you the good after you have paid? How do you know if the product will work? This is a worry for you, but it is also a worry for any reputable seller. Sellers want you to trust them, so there are mechanisms to allow you to find out about sellers. On the eBay page, you can find detailed information about the seller, including a number—called a feedback score—that indicates the number of positively rated sales by that seller. If you dig a bit deeper, you can even find reviews of the performance of the seller.

- Time remaining in the auction. Online auctions have a fixed time limit. When you go to the auction site for a particular good, you will see the amount of time left in the auction. Much of the action in an auction often comes very near the end of the bidding.

- Means of payment. When you buy a good on eBay, you are not able to simply give the seller some cash. The means of payment accepted by the seller are indicated in the auction information. In many cases, sellers use an electronic payment system, such as PayPal.

- Means of delivery. The seller must have a way of shipping the good to you—perhaps via FedEx or another package delivery service. The auction specifies who pays the cost of shipping.

- Reserve price. The seller will frequently specify a minimum price, called a reserve price. As a potential buyer, however, you will not see the actual reserve price; the only information you will see is whether or not the reserve price has been reached. A natural reserve price for the seller is her valuation of the good. (More precisely, the reserve price would also include the fee that the seller must pay to eBay in the event of a sale. The only reason for a seller to set a higher valuation is if she thinks she might do better trying to auction the good again at some point in the future rather than settling for a low price in the current auction.)

You participate as a buyer in an eBay auction by placing a bid. For some products, you also have an option of clicking “Buy It Now,” where you can purchase the good immediately. In other words, sellers sometimes make a take-it-or-leave it offer as well as offer an auction. To understand the details of the bidding process, look first at the description of how to bid on eBay:

Once you find an item you’re interested in, it’s easy to place a bid. Here’s how:

- Once you’re a registered eBay member, carefully look over the item listing. Be sure you really want to buy this item before you place a bid.

- Enter your maximum bid in the box at the bottom of the page and then click the Place Bid button.

- Enter your User ID and password and then click the Confirm Bid button. That’s it! eBay will now bid on your behalf up to the maximum amount you’re willing to pay for that item.

You’ll get an email confirming your bid. At the end of the listing, you’ll receive another email indicating whether you’ve won the item with an explanation of next steps.eBay Inc., “Help: How to Bid,” accessed March 14, 2011, http://pages.ebay.com/help/new/contextual/bid.html.

Because participants in an eBay auction are not all present to bid at the same time, eBay bids for you. All you have to do is to tell it how much you are willing to pay, and eBay takes over. This is known as “proxy bidding” or “automatic bidding.”

The exact way in which eBay bids for you is not transparent from this description. It works as follows. Once you input your maximum bid, eBay compares this to the highest existing bid. If your maximum bid is higher than the existing highest bid, then eBay raises the bid by an increment on your behalf. Unless someone bids more, you will win the auction. If someone does bid more (the maximum bid exceeds the highest bid), then you, by proxy, will respond. In this way, the highest bid increases. This process ends with the item going to the bidder with the highest maximum bid. However, the buyer does not pay the amount of the maximum bid. The buyer pays the amount of the next highest bid, plus the increment.

Let us see how this works through an example. Suppose there are two buyers who put in maximum bids of $100 and $120 for a cell phone. Suppose that the increment is $1 and the bidding starts at $50. Because the maximum bids exceed $50, the highest bid will increase by increments of $1 until reaching $100. At this point, the higher of the two maximums, $120, will cause the highest bid to increase by another increment to $101. After this, there is no further action: the other bidder effectively drops out of the auction. The item goes to the buyer who bid $120, and he pays a price of $101 (provided this exceeds the seller’s reserve price).

A Decision Rule for Bidding on eBay

Now that you understand how the auction works, you must decide how to bid. Suppose there is only one auction for the good you want (rather than multiple sellers of similar goods). In this case, there is a remarkably simple decision rule to guide your bidding.

- Decide on your valuation of the good—that is, the most you would be willing to pay for it.

- Bid that amount.

This seems surprising. Your first reaction might well be that it is better to bid less than your valuation. But here is the key insight: the amount you actually pay if you win the auction doesn’t depend on your bid. Your bid merely determines whether or not you win the auction.

If you pursue this strategy and win the auction, you will gain some surplus: the amount you pay will be less than the valuation you place on the good. If you don’t win the auction, you get nothing. So winning the auction is better than not winning. If you bid more than your valuation, then there is a chance that you will have to pay more than your valuation. In particular, if the second-highest bidder puts in a bid that exceeds your valuation, then you will lose surplus. So this does not seem like a good strategy. Finally, if you bid less than your valuation, there is a chance that you won’t win the auction even though you value the good more highly than anyone else. Therefore, you will lose the chance of getting some surplus. This is also not a good strategy.

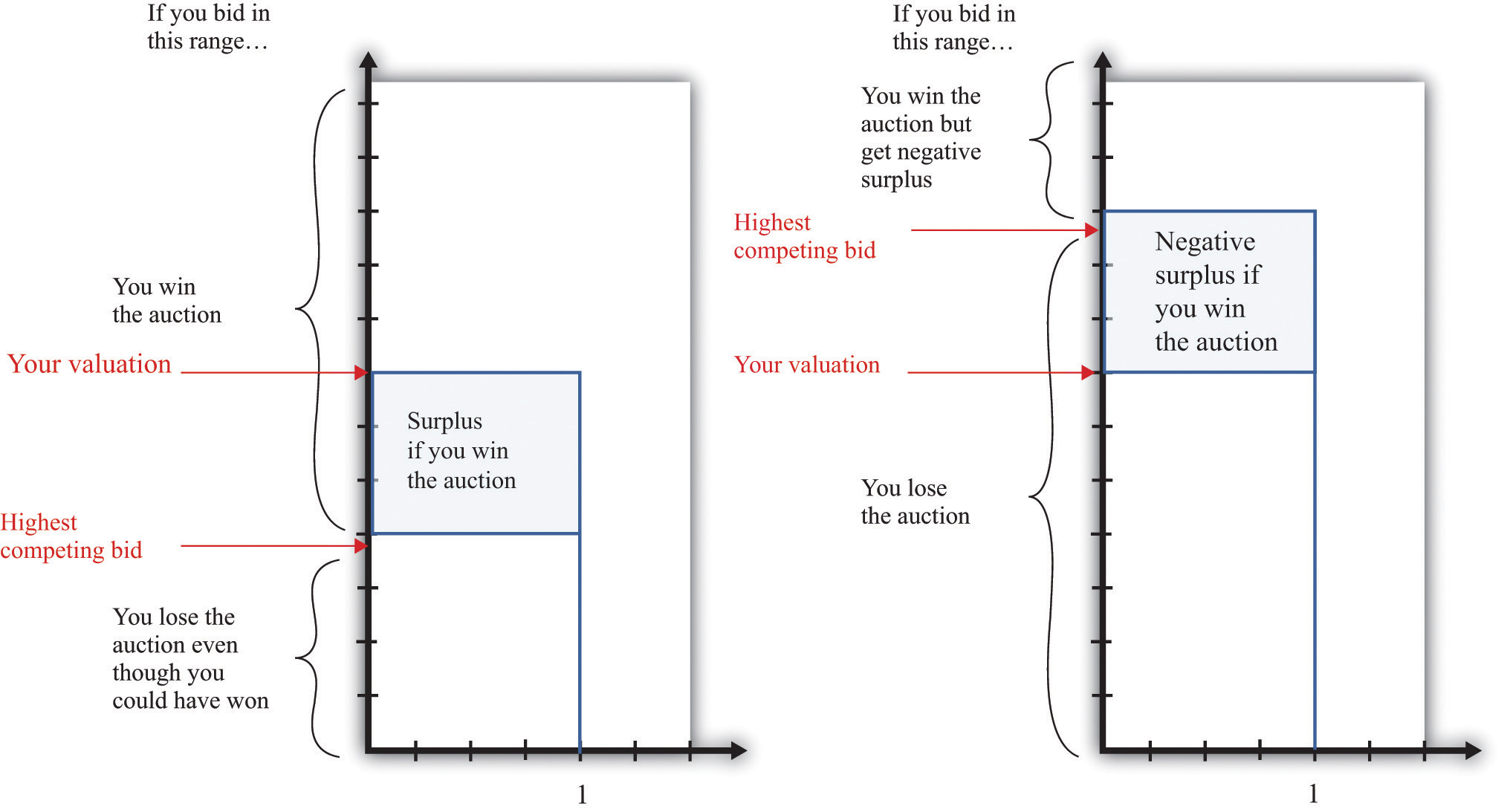

Figure 5.8 "Why You Should Bid Your Valuation in an eBay Auction" illustrates one way of thinking about this. There are two possibilities: either your valuation is bigger than the highest competing bid or your valuation is smaller than the highest competing bid. We don’t have to know anything about how other bidders are making their decisions. Part (a) of Figure 5.8 "Why You Should Bid Your Valuation in an eBay Auction" shows the first case. Here, there is a risk that you will lose out on surplus that you could have received. If you bid below the competing bid, you will lose the auction and hence lose out on the surplus. The surplus is the difference between your valuation and the competing bid, minus the increment.

Figure 5.8 Why You Should Bid Your Valuation in an eBay Auction

These illustrations show why you should always bid your valuation on eBay.

Part (b) of Figure 5.8 "Why You Should Bid Your Valuation in an eBay Auction" shows the case where your valuation is less than the competing bid. Here the risk is that you will win the auction and then regret it. If you bid an amount greater than the competing bid, then you will win the auction, but the amount you will have to pay exceeds your valuation. Your loss is the difference between the competing bid and your valuation, plus the increment.

Although automatic bidding by proxy sounds very fancy, the eBay auction is really the same as “English auctions” that are familiar from television and movies. In an English auction, an auctioneer stands at the front of the room and invites bids. Bidding increases in increments until all but one bidder drops out. The winning bidder pays the amount of his bid. The winning bidder therefore pays an amount equal to the highest competing bid, plus the increment, just as in the eBay auction. The amount that she wins is her valuation minus the price she pays, just as in the eBay auction.

The bidding in an English auction can be exciting to watch; you can also have the excitement of seeing how bids evolve on eBay (at least if you are willing to keep logging on and hitting the “refresh” button). But we could also imagine that eBay could do something simpler. It could carry out a “Vickrey auction,” which is named after its inventor, the Nobel-prize-winning economist William Vickrey. In a Vickrey auction, the auctioneer (1) collects all the bids, (2) awards victory in the auction to the highest bidder, and (3) makes this person pay an amount equal to the second-highest bid.

The Vickrey auction sometimes goes by the more technical name of a second-price sealed-bid auctionAn auction in which all bidders submit a single secret bid to the auctioneer, the winner is the person who submits the highest bid, and the winner pays an amount equal to the second-highest bid.. Most people think this kind of auction sounds very odd when they first hear of it. Why make the winner pay the second-highest bid? Yet it is almost exactly the same as the eBay auction or the English auction. In those auctions, as in the Vickrey auction, the winner is the person with the highest bid, and the winner pays the amount of the second-highest bid (plus the increment). The only difference is that there is no increment in the Vickrey auction; because the increment is typically a very small sum of money, this is a minor detail.

Selling on eBay

Sellers on eBay typically provide information on the product being sold. This is often done by creating a small web page that describes the object and includes a photograph. Sellers also pay a listing fee to eBay for the right to sell products. They also specify the costs for shipping and handling. After the sale is completed, the buyer and the seller communicate about the shipping, and the buyer makes a payment. Then the seller ships the product, pays eBay for the right to sell, and pockets the remainder.

As we mentioned previously, the buyer can provide feedback on the transaction with the seller. This feedback is important to the seller because transactions require some trust. A seller who has built a reputation for honesty will be able to sell more items, potentially at a higher price.

An Economic Perspective on Auctions

As an individual participating in an auction, you have two concerns: (1) whether or not you win and (2) how much you have to pay. As economists observing from outside, there are other perspectives. Auctions play a very valuable role in the economy. They represent a leading way in which goods are bought and sold—that is, they represent a mechanism for trade.

As we have already stated, voluntary trade is a good thing because it creates value in the economy. Every transaction allows a good or service to be transferred from someone who values it less to someone who values it more. The English auction, such as on eBay, is attractive to economists because it does something more. It ensures that the good or the service goes to the person who values it the most—that is, it ensures that the outcome is efficient. It also has the fascinating feature that it induces people to reveal their valuations through their bids.

eBay is just one example of the many auctions you could participate in. There are auctions for all types of goods: treasury securities, art, houses, the right to broadcast in certain ranges of the electromagnetic spectrum, and countless others. These auctions differ not only in terms of the goods traded but also in their rules. For example, firms competing for a contract to improve a local road may submit sealed bids, with the contract going to the lowest bidder to minimize the costs of the project. Of course, other elements of the bid, including the reputation of the bidder, may also be taken into account.

Complications

The eBay auction sounds almost too good to be true. It is easy to understand, brings forth honest bids, and allocates the good to the person who values it the most. Are there any problems with this rosy picture?

Multiple Sellers

Suppose you have a video-game system for sale. You can put it up for auction on eBay, but you must be aware that many other people could be listing the identical item. What will happen?

First, your potential buyers will most likely look (and bid) at multiple auctions, not only your auction. Second, potential buyers will not be eager to bid in your auction. After all, if they don’t win your auction, they can always hope for better luck in another auction. It follows that buyers may decide it is no longer such a good strategy to bid their valuations. Buyers who bid their valuations might end up paying a high price if they win an auction where someone else placed a relatively high bid. Such buyers might be more successful taking the chance of losing one auction and winning another in which the bidding is lower. As buyers monitor other auctions, they will also start to get a sense of how much other people are willing to pay and will adjust their bidding accordingly.

Unfortunately, we can’t give you such simple advice about what to do as a buyer in these circumstances. It is not easy to develop the best bidding strategy. In fact, problems like this can be so hard that even expert auction theorists have not fully worked them out.

Tacit Collusion

Another concern is that bidders might want to find some way to collude. As a simple example, suppose there are three bidders for a good with an increment of $1. One bidder has a valuation of $50, one has a valuation of $99, and one has a valuation of $100. In an eBay auction, the winning bid would be $100, but the winner would end up with no surplus (because he would pay $99 plus the $1 increment). Now suppose that the two high-value bidders make an agreement. As soon as the third bidder drops out, they toss a coin. If it comes up heads, Mr. $99 drops out. If it comes up tails, Ms. $100 drops out.

This means that with 50 percent probability, Ms. $100 wins, pays $51, and gets a surplus of $49. With 50 percent probability Mr. $99 wins, pays $51, and gets a surplus of $48. Both buyers prefer this. It’s certainly better for Mr. $99, who had no chance of winning before. It is also better for Ms. $100 because even though she may no longer win the auction, she stands to get some surplus if she does win. Of course, the seller wouldn’t like this arrangement at all. And the dispassionate economist observing from afar doesn’t like it either because sometimes the good may not go to the person who values it the most.

Explicit collusion of this type may very well be illegal, and it is also very hard to carry out. Yet it may be possible for buyers to collude indirectly, and there is speculation that such collusion is sometimes observed on eBay.

The Winner’s Curse

We have been supposing throughout that potential buyers know their own valuations of the good being auctioned. In most circumstances, this seems reasonable. Valuations are typically a personal matter that depend on the tastes of the individual buyer.

Occasionally, however, a good with an objective monetary value that is unknown to potential buyers may be auctioned. A classic example is the drilling rights to an oilfield. There is a certain amount of oil in the ground, and it will earn a certain price on the market. However, bidders do not know these values in advance and must make their best guess.

It is easiest to see what can happen here with a numerical example. Suppose the true (but unknown) value of an oilfield is $100 million. Suppose there are five bidders, whose guesses as to the value of the oilfield are summarized in Table 5.1 "Valuations of Different Bidders in a Winner’s Curse Auction". Notice that these bidders are right on average, but two overestimate the value of the field, and two underestimate it. Imagine that the bidders decide to follow the strategy that we recommended earlier and bid up to their best guess. Bidder E will win. He will have to pay the second-highest bid of $105 million, which is more than the oilfield is worth. He will lose $5 million.

Table 5.1 Valuations of Different Bidders in a Winner’s Curse Auction

| Bidder A | Bidder B | Bidder C | Bidder D | Bidder E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valuation ($ million) | 90 | 95 | 100 | 105 | 110 |

The problem here is that the person who will win the auction is the person who makes the worst overestimate of the value of the field. Evidently it is not a good strategy in this auction to bid your best guess. You should recognize that your best guess may be inaccurate, and if you overestimate badly, you may win the auction but lose money. This phenomenon is known as the winner’s curseThe idea that the winner of an auction may end up paying more than the good is actually worth because the true value of the good is unknown to the bidders.. Your best strategy is therefore to bid less than you actually think the oilfield is worth. But how much less should you bid? That, unfortunately, is a very hard question for which there is no simple answer. It depends on how accurate you think your guess is likely to be and how accurate you think other bidders’ guesses will be.

Key Takeaways

- On eBay, the best strategy is to bid your true valuation of the object.

- Auctions, like eBay, serve to allocate goods from sellers to buyers.

- If the winner’s curse if present, then you will want to bid less than your estimate of the value of the object.

Checking Your Understanding

- Suppose you bid less than your valuation on eBay. Explain how you could do better by bidding a little more.

- Why didn’t the winner’s curse have an effect on your bidding in eBay?