This is “eBay and craigslist”, chapter 5 from the book Theory and Applications of Microeconomics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 5 eBay and craigslist

Buying on the Internet

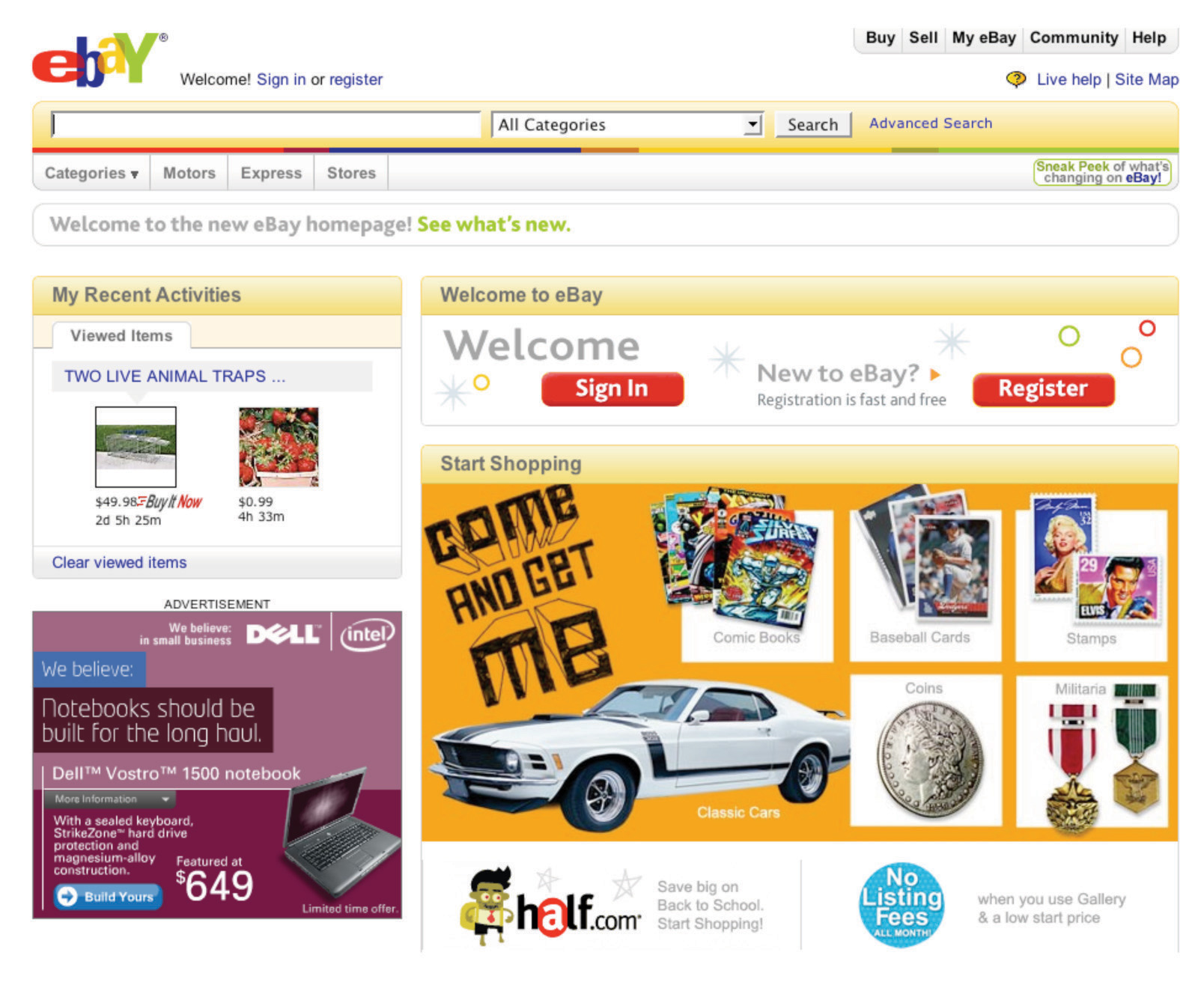

eBay is one of the most famous sites on the Internet (http://www.ebay.com; Figure 5.1 "The eBay Home Page"). It was founded in 1995 and is now a very large company, with $60 billion in sales in 2009 and over 90 million active users worldwide.See eBay Inc., “Who We Are,” accessed February 24, 2011, http://www.ebayinc.com/who. One of the many ways in which the Internet is changing the world is that there are now ways of buying and selling—such as eBay—that were completely unavailable to people 20 years ago.

Figure 5.1 The eBay Home Page

In or around the second and third centuries BCE, the island of Delos, in Greece, was a major center of trade—both of goods and slaves. At its height of activity, Delos, an island of five square kilometers, had a population of about 25,000 people.MyKonos Web, “History of Delos,” accessed January 25, 2011, http://www.mykonos-web.com/mykonos/delos_history.htm. This means Delos was about as densely populated as modern-day cities such as Istanbul, London, Chicago, Rio de Janeiro, or Vancouver. Visitors today see different things when they visit the ruins of Delos. Some see dusty pieces of shattered rock; others see the remains of a great culture. An economist sees the ruins of a trading center: a place where people such as the trader shown in Figure 5.2 "A Trader in Delos" were, in a sense, the eBay of their times.

Figure 5.2 A Trader in Delos

Delos and eBay are separated by almost two and a half millennia of history, yet both are founded on a basic human activity: the trading of goods and services. How basic? Consider the following.

- Children learn to trade at an early age. First graders may be trading Pokémon cards before they have even learned the meaning of money.

- In prisoner-of-war camps during World War II, prisoners would receive occasional parcels from the Red Cross, containing items such as chocolate bars, cigarettes, jam, razor blades, writing paper, and so on. There was extensive trading of these items. In some cases, cigarettes even started to play the role of money.For the classic discussion of trade in a prisoner-of-war camp, see R. A. Radford, “The Economic Organisation of a P.O.W. Camp,” Economica (New Series) 12, no. 48 (1945): 189–201.

- In Nazi concentration camps, where people lived close to starvation in conditions of extreme danger and deprivation, the prisoners traded with each other. They traded scraps of bread, undergarments, spoons, basic medicines, and even tailoring services.Jill Klein, “Calories for Dignity: Fashion in the Nazi Concentration Camp,” Advances in Consumer Research 15 (2003): 34–37.

Trade has played a central role in determining where many of us live today.

- In England, you will find the town of Market Harborough; in Germany, you can find Markt Isen; in Sweden, Lidköping. Markt and köping both mean market. These towns, and many others like them, date from the medieval period and, as their names suggest, owe their existence to the markets that were established there.

- Many of the great cities of the world developed in large part as ports, where goods were imported and exported. London, New Orleans, Hong Kong, Cape Town, Singapore, Amsterdam, and Montreal are a few examples.

Much of economics is about how we interact with each other. We are not alone in the economic world. We buy goods and services from firms, retailers, and each other. We likewise sell goods and services, most notably our labor time. In this chapter, we investigate different kinds of economic interactions and answer two of the most fundamental questions of economics:

- How do we trade?

- Why do we trade?

Road Map

The chapter falls naturally into two parts corresponding to these two questions. We begin by thinking about the ways in which individuals exchange goods and services.

In modern economies, most trade is highly disintermediated. You usually don’t buy a good from its producer. Perhaps the producer sells the good to a retail store that then sells to you. Or perhaps the good is first sold to a wholesaler who then sells to a retailer who then sells to you. Goods are often bought and sold many times before you get the opportunity to buy them.Such transactions are the focus in Chapter 6 "Where Do Prices Come From?" and Chapter 7 "Why Do Prices Change?". For the moment, however, we have a different emphasis. We do not yet get into the details of retailing in the economy but instead focus on trade among individuals—the kind of transaction that you can carry out on eBay and craigslist.

Specifically, we want to understand how potential buyers and sellers are matched up. We also want to know what determines the prices at which people exchange goods and services. Broadly speaking, prices can be established in the following ways.

- Some prices are the result of bargaining and negotiation. If you buy a car or a house, you will engage in a one-on-one negotiation with the seller in which there will typically be several rounds of offers and counteroffers before a final price is agreed on. Similarly, if you go to street markets in many countries in the world, you will not find posted prices but will have to bargain and haggle.

- Some prices are determined by auction, such as trinkets sold on eBay and antiques sold by Christie’s. Auctions are a type of bargaining that must follow some preset rules.

- Some prices are chosen by the seller: she simply displays a price at which she is willing to sell a unit of the good or service. Even this is a very simple type of bargaining called the “take-it-or-leave-it offer.” The seller posts a price (an “offer”), and prospective buyers then have a simple choice: either they buy at that price (they “take it”) or they do not buy (they “leave it”).

Take-it-or-leave-it offers are the most common form of price-setting in retail markets. The prices displayed in your local supermarket can be thought of as thousands of take-it-or-leave-it offers that the supermarket makes to you and other shoppers. Whenever you go to the supermarket, you reject most of these offers (meaning you don’t buy most of the goods on display), but you accept some of them. Take-it-or-leave-it offers also occur when individuals trade. Classified advertisements in newspapers or on Internet sites like craigslist typically involve take-it-or-leave-it offers.

Once we understand how individuals trade with one another, we turn to an even more basic question: why do we trade? Whether we are talking about first graders swapping Pokémon cards, the purchase of a camera on eBay, the auction of a Renoir painting at Sotheby’s, or traders in the Mediterranean islands over two millennia ago, there is one reason for trade: I have something you want, and you have something I want. (In many cases, one of these “somethings” is money. Keep in mind, though, that people don’t want money for its own sake; they want money to buy goods and services.)

We therefore explain how differences in what we have and what we want provide a motive for trade and how such trade creates value in the economy. Then we go deeper. In a modern economy, trade is an essential part of life. We consume a large number of goods and services, but we play a role in the production of very few. Put differently, modern economies exhibit a great deal of specialization. We carefully investigate how specialization lies right at the heart of the gains from trade.