This is “Social Security in Crisis?”, section 28.3 from the book Theory and Applications of Economics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

28.3 Social Security in Crisis?

Learning Objectives

After you have read this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What is the current state of the Social Security system in the United States?

- What are some of the policy choices being considered?

The Social Security system in the United States went into deficit in 2010: tax receipts were insufficient to cover expenditures. This was largely because the recession led to reduced receipts from the Social Security tax. However, the Social Security Board of Trustees warns that “[a]fter 2014, cash deficits are expected to grow rapidly as the number of beneficiaries continues to grow at a substantially faster rate than the number of covered workers.”“A Summary of the 2011 Annual Reports: Social Security and Medicare Boards of Trustees,” Social Security Administration, accessed June 24, 2011, http://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TRSUM/index.html.

It is hard to reconcile these statements with the model that we developed in Section 28.1 "Individual and Government Perspectives on Social Security" and Section 28.2 "A Model of Consumption". If Social Security is an irrelevance, why is there so much debate about it, and why is there so much concern about its solvency? The answer is that our model was too simple. The framework we have developed so far is a great starting point because it tells us about the basic workings of Social Security in a setting that is easy to understand. Don’t forget, though, that our discussion was built around a pay-as-you-go system in a world where the ratio of retirees to workers was not changing. Now we ask what happens if we complicate the demography of our model to make it more realistic.

The Baby Boom

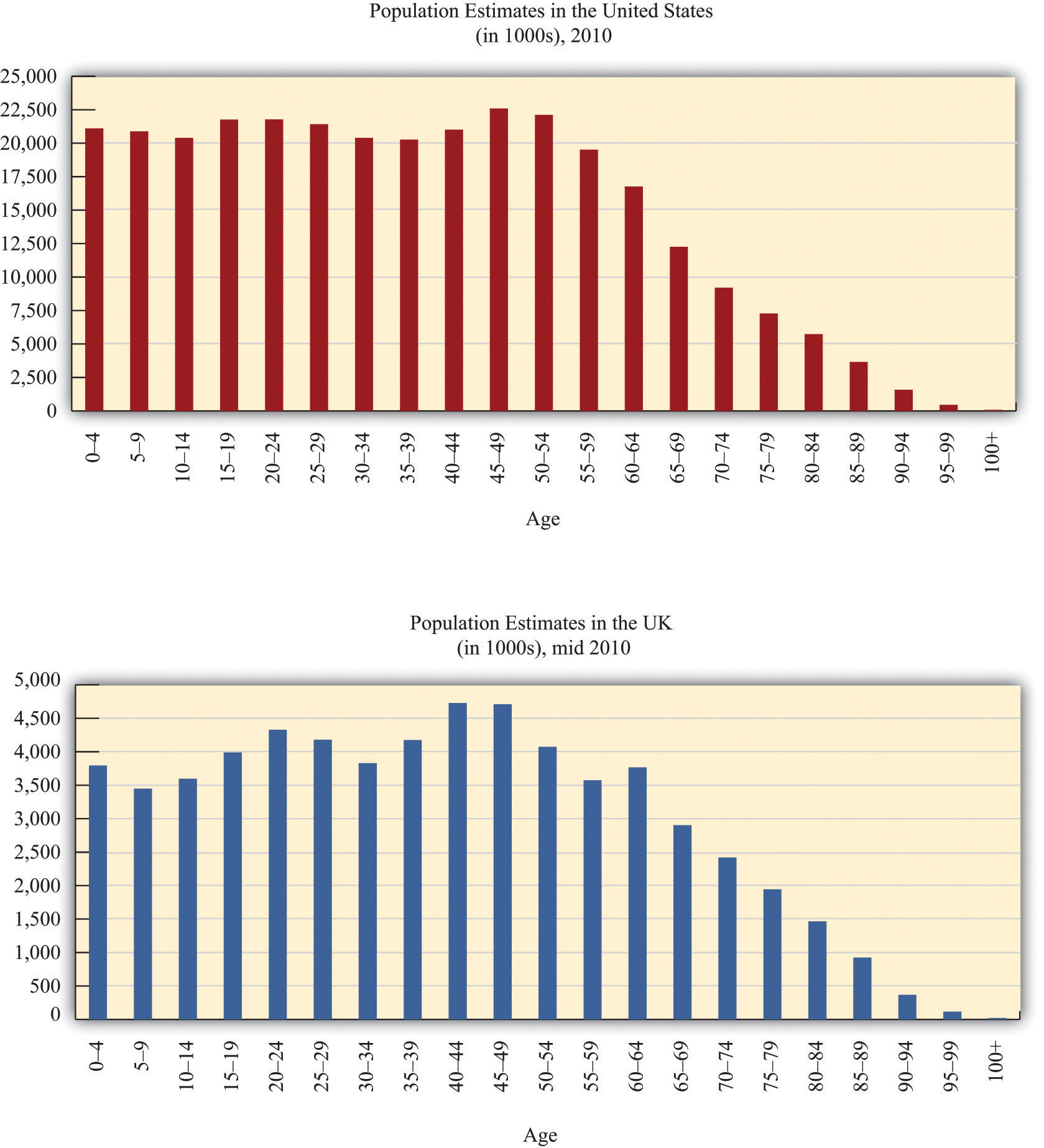

During the period directly following World War II, the birthrate in many countries increased significantly and remained high for the next couple of decades. People born at this time came to be known—for obvious reasons—as the baby boom generation. The baby boomers in the United States and the United Kingdom are clearly visible in Figure 28.6 "The Baby Boom in the United States and the United Kingdom", which shows the age distribution of the population of those countries. If babies were being born at the same rate, you would expect to see fewer and fewer people in each successive age group. Instead, there is a bulge in the age distribution around ages 35–55. (Interestingly, there is also a second baby boomlet visible, as the baby boomers themselves started having children.)

Figure 28.6 The Baby Boom in the United States and the United Kingdom

If the same number of people were born every year, then a bar chart of population at different age groups would show fewer and fewer people in each successive age group. Instead, as these pictures show, the United States and the United Kingdom had a “baby boom”: an unusually large number of children were born in the decades immediately following World War II. In 2010, this generation is in late middle age.

Source: US Census Bureau, International Data Base, http://www.census.gov/population/international/data/idb/informationGateway.php.

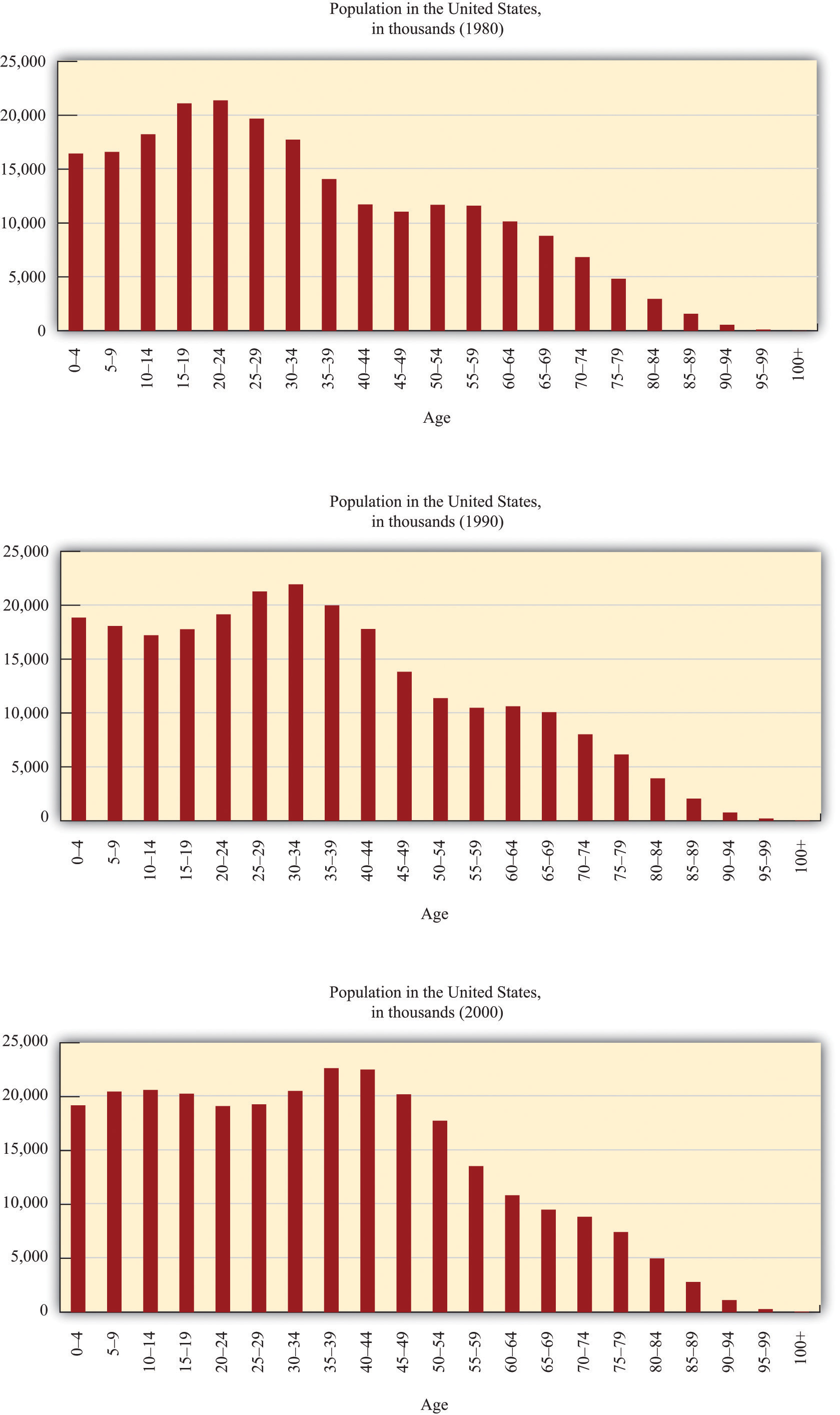

Figure 28.7 "The US Baby Boom over Time" presents the equivalent US data for 1980, 1990, and 2000, showing the baby boom working its way through the age distribution.

Figure 28.7 The US Baby Boom over Time

These pictures show the age distribution of the population as the baby boom generation gets older. The “bulge” in the age distribution shifts rightward. In 1980, the baby boomers were young adults. By 2000, even the youngest baby boomers were in middle age.

Source: US Census Bureau, International Data Base, http://www.census.gov/population/international/data/idb/informationGateway.php.

As the baby boom generation makes its way to old age, it is inevitable that the dependency ratioThe ratio of retirees to workers.—the ratio of retirees to workers—will increase dramatically. In addition, continuing advances in medical technology mean that people are living longer than they used to, and this too is likely to cause the dependency ratio to increase. The 2004 Economic Report of the President predicted that the dependency ratio in the United States will increase from 0.30 in 2003 to 0.55 in 2080.Economic Report of the President (Washington, DC: GPO, 2004), accessed July 20, 2011, http://www.gpoaccess.gov/usbudget/fy05/pdf/2004_erp.pdf. Roughly speaking, in other words, there are currently about three workers for every retiree, but by 2080 there will only be two workers per retiree.

A Baby Boom in Our Model

In our framework, we assumed that there was always one person alive at each age. This meant that the number of people working in any year was the same as the working life of an individual. Likewise, we were able to say that the number of people retired at a point in time was the same as the length of the retirement period.

Here is a simple way to represent a baby boom: Let us suppose that, in one year only, two people are born instead of one. When the extra person enters the work force, the dependency ratio will decrease—there is still the same number of retirees, but there are more workers. If Social Security taxes are kept unchanged and the government continues to keep the system in balance every year, then the government can pay out higher benefits to retirees. For 45 years, retirees can enjoy the benefits of the larger workforce.

Eventually, though, the baby boom generation reaches retirement age. At that point the extra individual stops contributing to the Social Security system and instead starts receiving benefits. What used to be a boon is now a problem. To keep the system in balance, the government must reduce Social Security benefits.

Let us see how this works in terms of our framework. Begin with the situation before the baby boom. We saw earlier that the government budget constraint meant that Social Security revenues must be the same as Social Security payments:

number of workers × Social Security tax = number of retirees × Social Security payment.If we divide both sides of this equation by the number of retirees, we find that

The first expression on the right-hand side (number of workers/number of retirees) is the inverse of the dependency ratio.

- When the baby boom generation is working. Once the additional person starts working, there is the same number of retirees, but there is now one extra worker. Social Security revenues therefore increase. If the government continues to keep the system in balance each year, it follows that the annual payment to each worker increases. The dependency ratio has gone down, so payments are larger. The government can make a larger payment to each retired person while still keeping the system in balance. Retirees during this period are lucky: they get a higher payout because there are relatively more workers.

- When the baby boom generation retires. Eventually, the baby boom generation will retire, and there will be one extra retiree each year until the baby boom generation dies. Meanwhile, we are back to having fewer workers. So when the baby boom generation retires, the picture is reversed. Social Security payments are higher than in our baseline case, and revenues are back to where they were before the baby boomers started working. Because there are now more retirees relative to workers—that is, the dependency ratio has increased—retirees see a cut in Social Security benefits.

If the Economic Report of the President figures are to be believed, the coming increase in the dependency ratio means that Social Security payments would have to decrease by about 45 percent if the Social Security budget were to be balanced every year. The reality is that this simply will not happen. First, the Social Security system does not simply calculate payouts on the basis of current Social Security receipts. In fact, there is a complicated formula whereby individuals receive a payout based on their average earnings over the 30 years during which they earned the most.Kaye A. Thomas, “Understanding the Social Security Benefit Calculation,” Fairmark, accessed July 20, 2011, http://www.fairmark.com/retirement/socsec/pia.htm. Of course, that formula could be changed, but it is unlikely that policymakers will completely abandon the principle that payments are based on past earnings. Second, retired persons already make up a formidable political lobby in the United States. As they become more numerous relative to the rest of the population, their political influence is likely to become even greater. Unless the political landscape changes massively, we can expect that the baby boom generation will have the political power to prevent a massive reduction in their Social Security payments.

Social Security Imbalances

To completely understand both the current situation and the future evolution of Social Security, we must make one last change in our analysis. Although the Social Security system was roughly in balance for the first half-century of its existence, that is no longer the case. Because payments are calculated on the basis of past earnings, it is possible for revenues to exceed outlays or be smaller than outlays. This means that the system is not operating on a strict pay-as-you-go basis.

When the government originally established Social Security, it set up something called the Social Security Trust Fund—think of it as being like a big bank account. Current workers pay contributions into this account, and the account also makes payments to retired workers. Under a strict pay-as-you-go system, the balance in the trust fund would always be zero. In fact, in some years payments to workers are smaller than tax receipts, in which case the extra goes into the Trust Fund. In other year payments exceed receipts, and the difference is paid for out of the Trust Fund.

To be more precise,

tax revenues = number of workers × Social Security taxes = number of workers × tax rate × incomeand

Social Security payments = number of retirees × Social Security payment.If tax revenues exceed payments, then the system is running a surplus: it is taking in more in income each period than it is paying out to retirees. Conversely, if payments exceed revenues, the system is in deficit. In other words,

Social Security surplus = number of workers × tax rate × income − number of retirees × Social Security payment.For the first half-century of Social Security, there was an approximate match between payments and receipts, although receipts were usually slightly larger than payments. In other words, rather than being exactly pay-as-you-go, the system typically ran a small surplus each year.“Trust Fund Data,” Social Security Administration, January 31, 2011, accessed July 20, 2011, http://www.ssa.gov/OACT/STATS/table4a1.html. Over the first half-century of the program, the Trust Fund accumulated slightly less than $40 billion in assets. This might sound like a big number, but it amounts to only a few hundred dollars per worker. The Social Security Trust Fund contains the accumulated surpluses of past years. It gets bigger or smaller over time depending on whether the surplus is positive or negative. For example,

Trust Fund balance this year = Trust Fund balance last year + Social Security surplus this year.(Strictly, that equation is true provided that we continue to suppose that the real interest rate is zero.) If tax revenues exceed payments, then there is a surplus, and the Trust Fund increases. If tax revenues are less than payments, then there is a deficit (or, to put it another way, the surplus is negative), so the Trust Fund decreases.

The small surpluses that have existed since the start of the system mean that the Trust Fund has been growing over time. Unfortunately, it has not been growing fast enough, and in 2010, the fund switched from running a surplus to running a deficit. There are still substantial funds in the system—almost a century’s worth of accumulated surpluses. But the dependency ratio is so high that those accumulated funds will disappear within a few decades.

Resolving the Problem: Some Proposals

We can use the life-cycle model of consumption/saving along with the government budget constraint to better understand proposals to deal with Social Security imbalances.

We saw that the surplus is given by the following equation:

Social Security surplus = number of workers × tax rate × income − number of retirees × Social Security payment.The state of the Social Security system in any year depends on five factors:

- The level of income

- The Social Security tax rate on income

- The size of the benefits

- The number of workers

- The number of retirees

Other things being equal, increases in income (economic growth) help push the system into surplus.The effect of economic growth is lessened because of the fact that Social Security payments are linked to past earnings. Higher growth therefore implies higher payouts as well as higher revenues. Still, on net, higher growth would help Social Security finances. A larger number of the population of working age also tends to push the system into surplus, as does a higher Social Security tax. On the other hand, if benefits are higher or there are more retirees, that tends to push the system toward deficit.

Increasing Taxes or Decreasing Benefits

Many of the proposals for reforming Social Security can be understood simply by examining the equation for the surplus. Remember that the number of workers × the tax rate × income is the tax revenue collected from workers, whereas the number of retirees × the Social Security payment is the total transfer payments to retirees. If the system is running a deficit, then to restore balance, either revenues must increase or payouts must be reduced.

The tax rate and the amount of the payment are directly under the control of the government. In addition, there is a ceiling on income that is subject to the Social Security tax ($106,800 in 2011). At any time, Congress can pass laws changing these variables. It could increase the tax rate, increase the income ceiling, or decrease the payment. If we simply think of the problem as a mathematical equation, then the solution is easy: either increase tax revenues or decrease benefits. Politics, though, is not mathematics. Politically, such changes are very difficult. Indeed, politicians often refer to increases in taxes and/or reductions in benefits as a political “third rail” (a metaphor that derives from the high-voltage electrified rail that provides power to subway trains—in other words, something not to be touched).

Another way to increase revenue is through increases in GDP. If the economy is expanding and output is increasing, then the government will collect more tax revenues for Social Security. There are no simple policies that guarantee faster growth, however, so we cannot plan on solving the problem this way.

Delaying Retirement

We have discussed the tax rate, the payment, and the level of income. This leaves the number of workers and the number of retirees. We can change these variables as well. Specifically, we can make the number of workers bigger and the number of retirees smaller by changing the retirement age. This option is frequently discussed. After all, one of the causes of the Social Security imbalance is the fact that people are living longer. So, some ask, if people live longer, should they work longer as well?

Moving to a Fully Funded Social Security System

The financing problems of Social Security stem from a combination of two things: demographic change and the pay-as-you-go approach to financing. Suppose that, instead of paying current retirees by taxing current workers, the government were instead simply to tax workers, invest those funds on their behalf, and then pay workers back when they are retired. Economists call this a fully funded Social Security systemA system in which the government taxes income and invests it on behalf of the household, paying back the saving with interest during retirement years.. In this setup, demographic changes such as the baby boom would not be such a big problem. When the baby boom generation was working, the government would collect a large amount of funds so that it would later have the resources to pay the baby boomers their benefits.

As an example, Singapore has a system known as the Central Provident Fund, which is in effect a fully funded Social Security system. Singaporeans make payments into this fund and are guaranteed a minimum return on their payments. In fact, Singapore sets up three separate accounts for each individual: one specifically for retirement, one that can be used to pay for medical expenses, and one that can be used for specific investments such as a home or education.

Some commentators have advocated that the United States should shift to a fully funded Social Security system, and many economists would agree with this proposal.“Economic Letter,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, March 13, 1998, accessed July 20, 2011, http://www.frbsf.org/econrsrch/wklyltr/wklyltr98/el98-08.html. This letter discussed the transition to a fully funded Social Security system. Were it to adopt such a system, the US government would not in the future have the kinds of problems that we currently face. Indeed, the Social Security reforms of the 1980s can be considered a step away from pay-as-you-go and toward a fully funded system. At that time, the government stopped keeping the system in (approximate) balance and instead started to build up the Social Security Trust Fund.

But this is not a way to solve the current crisis in the United States. It is already too late to make the baby boomers pay fully for their own retirement. Think about what happened when Social Security was first established. At that time, old workers received benefits that were much greater than their contributions to the system. That generation received a windfall gain from the establishment of the pay-as-you-go system. That money is gone, and the government cannot get it back.

Suppose the United States tried to switch overnight from a pay-as-you-go system to a fully funded system. Then current workers would be forced to pay for Social Security twice: once to pay for those who are already retired and then a second time to pay for their own retirement benefits. Obviously, this is politically infeasible, as well as unfair. Any realistic transition to a fully funded system would therefore have to be phased in over a long period of time.

Privatization

Recent discussion of Social Security has paid a lot of attention to privatization. Privatization is related to the idea of moving to a fully funded system but with the additional feature that Social Security evolves (at least in part) toward a system of private accounts where individuals have more control over their Social Security savings. In particular, individuals would have more choice about the assets in which their Social Security payments would be invested. Advocates of this view argue that individuals ought to be responsible for providing for themselves, even in old age, and suggest that private accounts would earn a higher rate of return. Opponents of privatization argue, as did the creators of Social Security in the 1930s, that a privatized system would not provide the assistance that elderly people need.

Some countries already have social security systems with privatized accounts. In 1981, Chile’s pay-as-you-go system was virtually bankrupt and replaced with a mandatory savings scheme. Workers are required to establish an account with a private pension company; however, the government strictly regulates these companies. The system has suffered from compliance problems, however, with much of the workforce not actually contributing to a plan. In addition, it turns out that many workers have not earned pensions above the government minimum, so in the end it is not clear that the private accounts are really playing a very important role. Recent reforms have attempted to address these problems, but it remains unclear how successful Chile’s transition to privatization will be.

As with the move to a fully funded Social Security system, a big issue with privatization is the transition period. If, for example, the government announced a plan today to privatize Social Security, it would have to deal with the fact that many retired people would no longer have Social Security income. Furthermore, many working people would have already paid into the program. Thus proposals to privatize Social Security must include a plan for dealing with existing retirees and those who have paid into the system through payroll taxes.

Some recent discussion has suggested, implicitly or explicitly, that privatization would help solve the current Social Security imbalance. This is misleading. By cutting off the payroll tax revenues, privatization makes the problem worse in the short run, not better. Although privatization is certainly a proposal that can be discussed on its own merits, it should be kept separate from the debate about how to balance existing Social Security claims with revenues.

Key Takeaways

- Many studies predict that, if there are no policy changes, the Social Security system will be bankrupt by the middle of this century. A main cause of this problem is demographic change: fewer workers are supporting more retirees, and life expectancies have increased.

- Some possible policy remedies include raising taxes on workers, reducing benefits, and increasing the retirement age.

Checking Your Understanding

- What is the dependency ratio? Why might it change over time?

- What is the Social Security Trust Fund?