This is “Liability Imposed by Signature: Agents, Authorized and Unauthorized”, section 19.1 from the book The Legal Environment and Business Law: Master of Accountancy Edition (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

19.1 Liability Imposed by Signature: Agents, Authorized and Unauthorized

Learning Objectives

- Recognize what a signature is under Article 3 of the Uniform Commercial Code.

- Understand how a person’s signature on an instrument affects liability if the person is an agent, or a purported agent, for another.

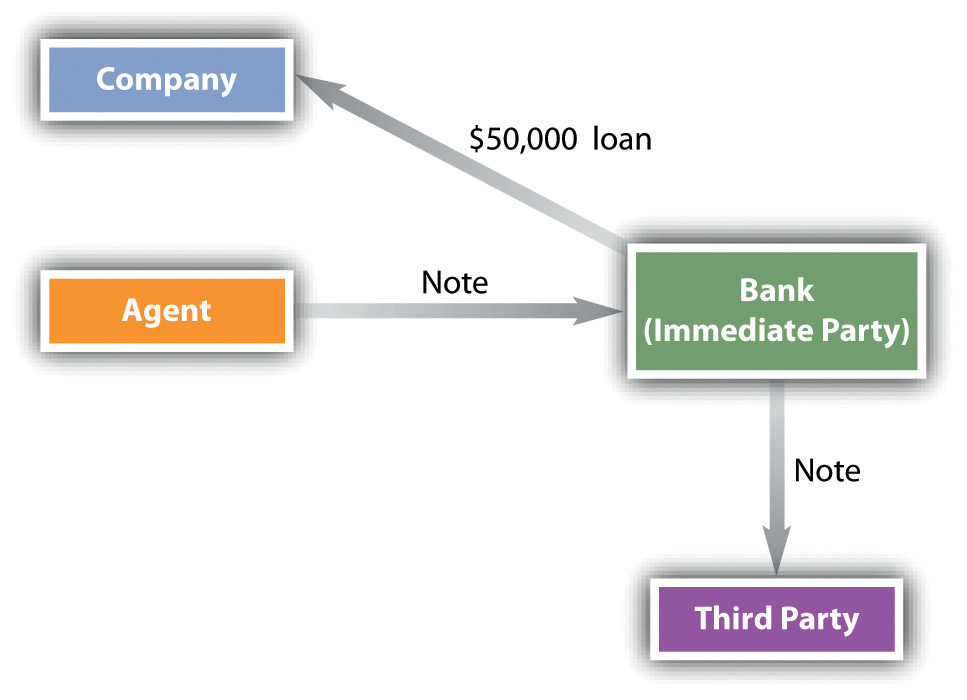

The liability of an agent who signs commercial paper is one of the most frequently litigated issues in this area of law. For example, Igor is an agent (treasurer) of Frank N. Stein, Inc. Igor signs a note showing that the corporation has borrowed $50,000 from First Bank. The company later becomes bankrupt. The question: Is Igor personally liable on the note? The unhappy treasurer might be sued by the bank—the immediate party with whom he dealt—or by a third party to whom the note was transferred (see Figure 19.1 "Signature by Representative").

Figure 19.1 Signature by Representative

There are two possibilities regarding an agent who signs commercial paper: the agent was authorized to do so, or the agent was not authorized to do so. First, though, what is a signature?

A “Signature” under the Uniform Commercial Code

Section 3-401 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) provides fairly straightforwardly that “a signature can be made (i) manually or by means of a device or machine, and (ii) by the use of any name, including any trade or assumed name, or by any word, mark, or symbol executed or adopted by a person with the present intention to authenticate a writing.”

Liability of an Agent Who Has Authority to Sign

Agents often sign instruments on behalf of their principals, and—of course—because a corporation’s existence is a legal fiction (you can’t go up and shake hands with General Motors), corporations can only act through their agents.

The General Rule

Section 3-402(a) of the UCC provides that a person acting (or purporting to act) as an agent who signs an instrument binds the principal to the same extent that the principal would be bound if the signature were on a simple contract. The drafters of the UCC here punt to the common law of agency: if, under agency law, the principal would be bound by the act of the agent, the signature is the authorized signature of the principal. And the general rule in agency law is that the agent is not liable if he signs his own name and makes clear he is doing so as an agent. In our example, Igor should sign as follows: “Frank N. Stein, Inc., by Igor, Agent.” Now it is clear under agency law that the corporation is liable and Igor is not.Uniform Commercial Code, Section 4-402(b)(1). Good job, Igor.

Incorrect Signatures

The problems arise where the agent, although authorized, signs in an incorrect way. There are three possibilities: (1) the agent signs only his own name—“Igor”; (2) the agent signs both names but without indication of any agency—“Frank N. Stein, Inc., / Igor” (the signature is ambiguous—are both parties to be liable, or is Igor merely an agent?); (3) the agent signs as agent but doesn’t identify the principal—“Igor, Agent.”

The UCC provides that in each case, the agent is liable to a holder in due course (HDC) who took the instrument without notice that the agent wasn’t intended to be liable on the instrument. As to any other person (holder or transferee), the agent is liable unless she proves that the original parties to the instrument did not intend her to be liable on it. Section 3-402(c) says that, as to a check, if an agent signs his name without indicating agency status but the check has the principal’s identification on it (that would be in the upper left corner), the authorized agent is not liable.

Liability of an “Agent” Who Has No Authority to Sign

A person who has no authority to sign an instrument cannot really be an “agent” because by definition an agent is a person or entity authorized to act on behalf of and under the control of another in dealing with third parties. Nevertheless, unauthorized persons not infrequently purport to act as agents: either they are mistaken or they are crooks. Are their signatures binding on the “principal”?

The General Rule

An unauthorized signature is not binding; it is—as the UCC puts it—“ineffective except as the signature of the unauthorized signer.”Uniform Commercial Code, Section 3-403. So if Crook signs a Frank N. Stein, Inc., check with the name “Igor,” the only person liable on the check is Crook.

The Exceptions

There are two exceptions. Section 4-403(a) of the UCC provides that an unauthorized signature may be ratified by the principal, and Section 3-406 says that if negligence contributed to an instrument’s alteration or forgery, the negligent person cannot assert lack of authority against an HDC or a person who in good faith pays or takes the instrument for value or for collection. This is the situation where Principal leaves the rubber signature stamp lying about and Crook makes mischief with it, making out a check to Payee using the stamp. But if Payee herself failed to exercise reasonable care in taking a suspicious instrument, both Principal and Payee could be liable, based on comparative negligence principles.Uniform Commercial Code, Section 3-406(b).

Key Takeaway

Under the UCC, a “signature” is any writing or mark used by a person to indicate that a writing is authentic. Agents often sign on behalf of principals, and when the authorized agent makes clear that she is so signing—by naming the principal and signing her name as “agent”—the principal is liable, not the agent. But when the agent signs incorrectly, the UCC says, in general, that the agent is personally liable to an HDC who takes the paper without notice that the agent is not intended to be liable. Unauthorized signatures (forgeries) are ineffective as to the principal: they are effective as the forger’s signature, unless the principal or the person paying on the instrument has been negligent in contributing to, or in failing to notice, the forgery, in which case comparative negligence principles are applied.

Exercises

- Able signs his name on a note with an entirely illegible squiggle. Is that a valid signature?

- Under what circumstances is an agent clearly not personally liable on an instrument?

- Under what circumstances is a forgery effective as to the person whose name is forged?