This is “Electronic Funds Transfers”, section 23.2 from the book The Law, Corporate Finance, and Management (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

23.2 Electronic Funds Transfers

Learning Objectives

- Understand why electronic fund transfers have become prevalent.

- Recognize some typical examples of EFTs.

- Know that the EFT Act of 1978 protects consumers, and recognize what some of those protections—and liabilities—are.

- Understand when financial institutions will be liable for violating the act, and some of the circumstances when the institutions will not be liable.

Background to Electronic Fund Transfers

In General

Drowning in the yearly flood of billions of checks, eager to eliminate the “float” that a bank customer gets by using her money between the time she writes a check and the time it clears, and recognizing that better customer service might be possible, financial institutions sought a way to computerize the check collection process. What has developed is electronic fund transfer (EFT), a system that has changed how customers interact with banks, credit unions, and other financial institutions. Paper checks have their advantages, but their use is decreasing in favor of EFT.

In simplest terms, EFT is a method of paying by substituting an electronic signal for checks. A “debit card,” inserted in the appropriate terminal, will authorize automatically the transfer of funds from your checking account, say, to the account of a store whose goods you are buying.

Types of EFT

You are of course familiar with some forms of EFT:

- The automated teller machine (ATM) permits you to electronically transfer funds between checking and savings accounts at your bank with a plastic ID card and a personal identification number (PIN), and to obtain cash from the machine.

- Telephone transfers or computerized transfers allow customers to access the bank’s computer system and direct it to pay bills owed to a third party or to transfer funds from one account to another.

- Point of sale terminals located in stores let customers instantly debit their bank accounts and credit the merchant’s account.

- Preauthorized payment plans permit direct electronic deposit of paychecks, Social Security checks, and dividend checks.

- Preauthorized withdrawals from customers’ bank accounts or credit card accounts allow paperless payment of insurance premiums, utility bills, automobile or mortgage payments, and property tax payments.

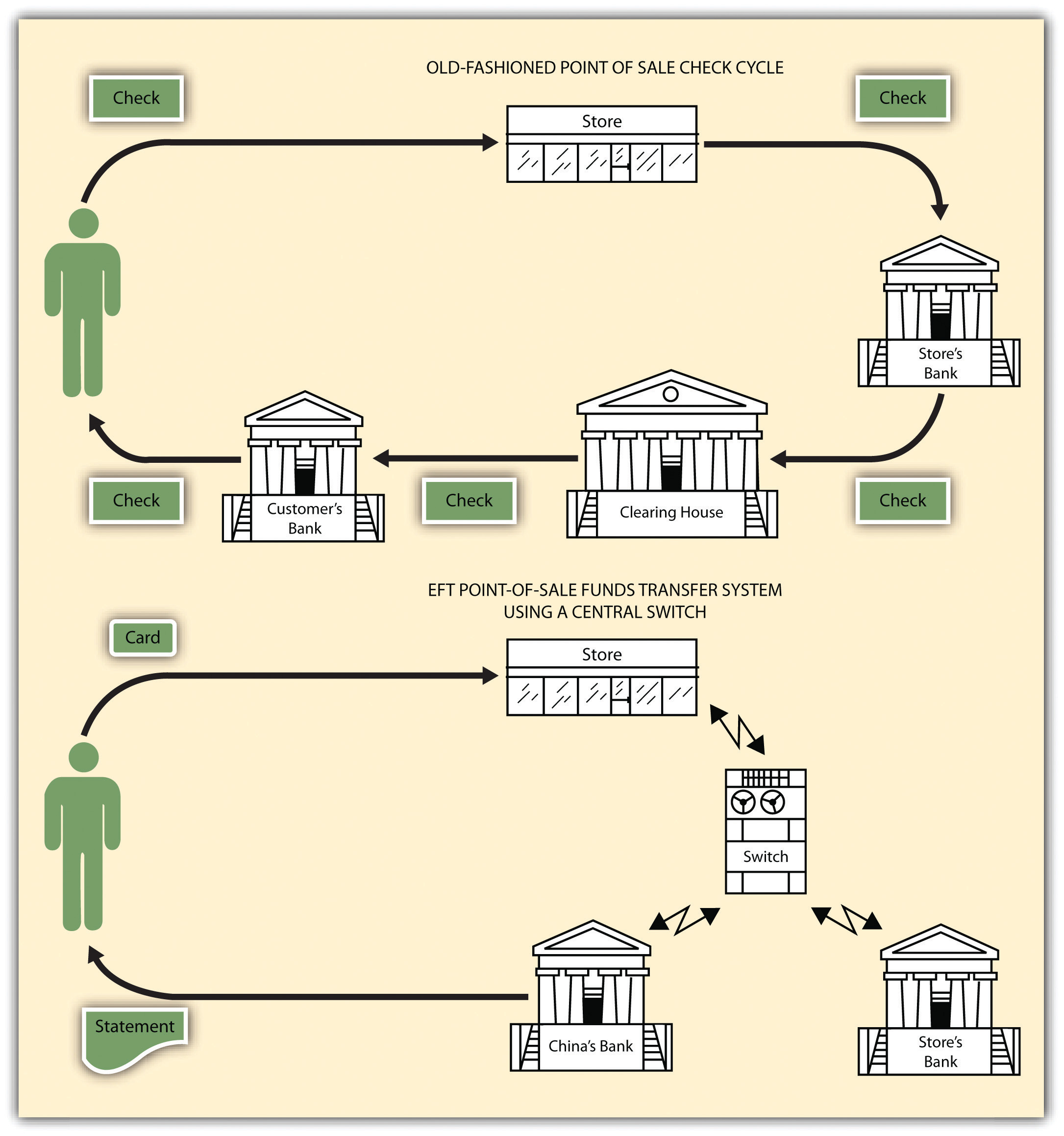

The “short circuit” that EFT permits in the check processing cycle is illustrated in Figure 23.2 "How EFT Replaces Checks".

Figure 23.2 How EFT Replaces Checks

Unlike the old-fashioned check collection process, EFT is virtually instantaneous: at one instant a customer has a sum of money in her account; in the next, after insertion of a plastic card in a machine or the transmission of a coded message by telephone or computer, an electronic signal automatically debits her bank checking account and posts the amount to the bank account of the store where she is making a purchase. No checks change hands; no paper is written on. It is quiet, odorless, smudge proof. But errors are harder to trace than when a paper trail exists, and when the system fails (“our computer is down”) the financial mess can be colossal. Obviously some sort of law is necessary to regulate EFT systems.

Electronic Fund Transfer Act of 1978

Purpose

Because EFT is a technology consisting of several discrete types of machines with differing purposes, its growth has not been guided by any single law or even set of laws. The most important law governing consumer transactions is the Electronic Fund Transfer Act of 1978Federal law that provides a basic framework establishing the rights, liabilities, and responsibilities of participants in electronic fund transfer systems.,FDIC, “Electronic Fund Transfer Act of 1978,” http://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/6500-1350.html. whose purpose is “to provide a basic framework establishing the rights, liabilities, and responsibilities of participants in electronic fund transfer systems. The primary objective of [the statute], however, is the provision of individual consumer rights.” This federal statute has been implemented and supplemented by the Federal Reserve Board’s Regulation E, Comptroller of the Currency guidelines on EFT, and regulations of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board. (Wholesale transactions are governed by UCC Article 4A, which is discussed later in this chapter.)

The EFT Act of 1978 is primarily designed to disclose the terms and conditions of electronic funds transfers so the customer knows the rights, costs and liabilities associated with EFT, but it does not embrace every type of EFT system. Included are “point-of-sale transfers, automated teller machine transactions, direct deposits or withdrawal of funds, and transfers initiated by telephone or computer” (EFT Act Section 903(6)). Not included are such transactions as wire transfer services, automatic transfers between a customer’s different accounts at the same financial institution, and “payments made by check, draft, or similar paper instrument at electronic terminals” (Reg. E, Section 205.2(g)).

Consumer Protections Afforded by the Act

Four questions present themselves to the mildly wary consumer facing the advent of EFT systems: (1) What record will I have of my transaction? (2) How can I correct errors? (3) What recourse do I have if a thief steals from my account? (4) Can I be required to use EFT? The EFT Act, as implemented by Regulation E, answers these questions as follows.

- Proof of transaction. The electronic terminal itself must be equipped to provide a receipt of transfer, showing date, amount, account number, and certain other information. Perhaps more importantly, the bank or other financial institution must provide you with a monthly statement listing all electronic transfers to and from the account, including transactions made over the computer or telephone, and must show to whom payment has been made.

- Correcting errors. You must call or write the financial institution whenever you believe an error has been made in your statement. You have sixty days to do so. If you call, the financial institution may require you to send in written information within ten days. The financial institution has forty-five days to investigate and correct the error. If it takes longer than ten days, however, it must credit you with the amount in dispute so that you can use the funds while it is investigating. The financial institution must either correct the error promptly or explain why it believes no error was made. You are entitled to copies of documents relied on in the investigation.

- Recourse for loss or theft. If you notify the issuer of your EFT card within two business days after learning that your card (or code number) is missing or stolen, your liability is limited to $50. If you fail to notify the issuer in this time, your liability can go as high as $500. More daunting is the prospect of loss if you fail within sixty days to notify the financial institution of an unauthorized transfer noted on your statement: after sixty days of receipt, your liability is unlimited. In other words, a thief thereafter could withdraw all your funds and use up your line of credit and you would have no recourse against the financial institution for funds withdrawn after the sixtieth day, if you failed to notify it of the unauthorized transfer.

- Mandatory use of EFT. Your employer or a government agency can compel you to accept a salary payment or government benefit by electronic transfer. But no creditor can insist that you repay outstanding loans or pay off other extensions of credit electronically. The act prohibits a financial institution from sending you an EFT card “valid for use” unless you specifically request one or it is replacing or renewing an expired card. The act also requires the financial institution to provide you with specific information concerning your rights and responsibilities (including how to report losses and thefts, resolve errors, and stop payment of preauthorized transfers). A financial institution may send you a card that is “not valid for use” and that you alone have the power to validate if you choose to do so, after the institution has verified that you are the person for whom the card was intended.

Liability of the Financial Institution

The financial institution’s failure to make an electronic fund transfer, in accordance with the terms and conditions of an account, in the correct amount or in a timely manner when properly instructed to do so by the consumer makes it liable for all damages proximately caused to the consumer, except where

1) the consumer’s account has insufficient funds;

2) the funds are subject to legal process or other encumbrance restricting such transfer;

3) such transfer would exceed an established credit limit;

4) an electronic terminal has insufficient cash to complete the transaction; or

5) a circumstance beyond its control, where it exercised reasonable care to prevent such an occurrence, or exercised such diligence as the circumstances required.

Enforcement of the Act

A host of federal regulatory agencies oversees enforcement of the act. These include the Comptroller of the Currency (national banks), Federal Reserve District Bank (state member banks), Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation regional director (nonmember insured banks), Federal Home Loan Bank Board supervisory agent (members of the FHLB system and savings institutions insured by the Federal Savings & Loan Insurance Corporation), National Credit Union Administration (federal credit unions), Securities & Exchange Commission (brokers and dealers), and the Federal Trade Commission (retail and department stores) consumer finance companies, all nonbank debit card issuers, and certain other financial institutions. Additionally, consumers are empowered to sue (individually or as a class) for actual damages caused by any EFT system, plus penalties ranging from $100 to $1,000. Section 23.4 "Cases", under “Customer’s Duty to Inspect Bank Statements” (Commerce Bank v. Brown), discusses the bank’s liability under the act.

Key Takeaway

Eager to reduce paperwork for both themselves and for customers, and to speed up the check collection process, financial institutions have for thirty years been moving away from paper checks and toward electronic fund transfers. These EFTs are ubiquitous, including ATMs, point-of-sale systems, direct deposits and withdrawals and online banking of various kinds. Responding to the need for consumer protection, Congress adopted the Electronic Fund Transfers Act, effective in 1978. The act addresses many common concerns consumers have about using electronic fund transfer systems, sets out liability for financial institutions and customers, and provides an enforcement mechanism.

Exercises

- Why have EFTs become very common?

- What major issues are addressed by the EFTA?

- If you lose your credit card, what is your liability for unauthorized charges?