This is “The Corporate Veil: The Corporation as a Legal Entity”, section 14.3 from the book The Law, Corporate Finance, and Management (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

14.3 The Corporate Veil: The Corporation as a Legal Entity

Learning Objectives

- Know what rights a corporate “person” and a natural person have in common.

- Recognize when a corporate “veil” is pierced and shareholder liability is imposed.

- Identify other instances when a shareholder will be held personally liable.

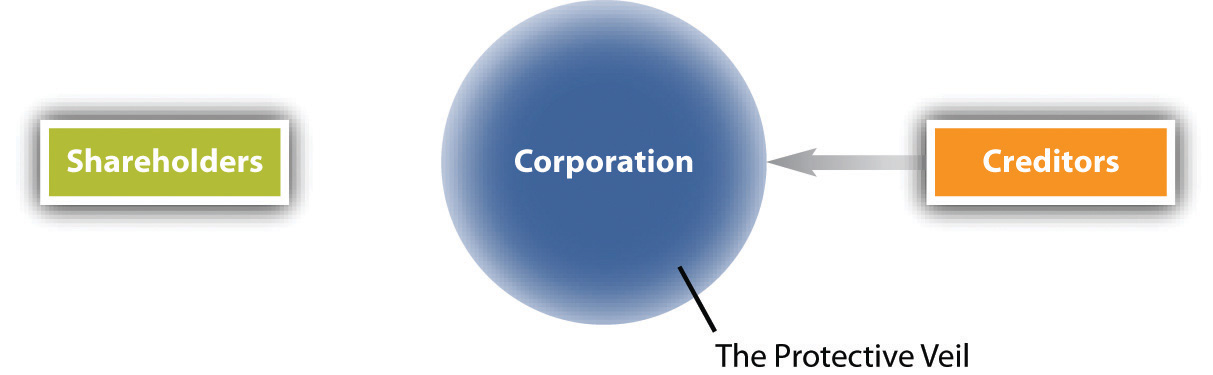

In comparing partnerships and corporations, there is one additional factor that ordinarily tips the balance in favor of incorporating: the corporation is a legal entity in its own right, one that can provide a “veil” that protects its shareholders from personal liability.

Figure 14.1 The Corporate Veil

This crucial factor accounts for the development of much of corporate law. Unlike the individual actor in the legal system, the corporation is difficult to deal with in conventional legal terms. The business of the sole proprietor and the sole proprietor herself are one and the same. When a sole proprietor makes a decision, she risks her own capital. When the managers of a corporation take a corporate action, they are risking the capital of others—the shareholders. Thus accountability is a major theme in the system of law constructed to cope with legal entities other than natural persons.

The Basic Rights of the Corporate “Person”

To say that a corporation is a “person”When corporations are granted the same rights as natural persons. does not automatically describe what its rights are, for the courts have not accorded the corporation every right guaranteed a natural person. Yet the Supreme Court recently affirmed in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010) that the government may not suppress the First Amendment right of political speech because the speaker is a corporation rather than a natural person. According to the Court, “No sufficient governmental interest justifies limits on the political speech of nonprofit or for-profit corporations.”Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. ___ (2010).

The courts have also concluded that corporations are entitled to the essential constitutional protections of due process and equal protection. They are also entitled to Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable search and seizure; in other words, the police must have a search warrant to enter corporate premises and look through files. Warrants, however, are not required for highly regulated industries, such as those involving liquor or guns. The Double Jeopardy Clause applies to criminal prosecutions of corporations: an acquittal cannot be appealed nor can the case be retried. For purposes of the federal courts’ diversity jurisdiction, a corporation is deemed to be a citizen of both the state in which it is incorporated and the state in which it has its principal place of business (often, the corporate “headquarters”).

Until relatively recently, few cases had tested the power of the state to limit the right of corporations to spend their own funds to speak the “corporate mind.” Most cases involving corporate free speech address advertising, and few states have enacted laws that directly impinge on the freedom of companies to advertise. But those states that have done so have usually sought to limit the ability of corporations to sway voters in public referenda. In 1978, the Supreme Court finally confronted the issue head on in First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti (Section 14.7.1 "Limiting a Corporation’s First Amendment Rights"). The ruling in Bellotti was reaffirmed by the Supreme Court in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. In Citizens United, the Court struck down the part of the McCain-Feingold ActThe Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA, McCain–Feingold Act, Pub.L. 107-155, 116 Stat. 81, enacted March 27, 2002, H.R. 2356). that prohibited all corporations, both for-profit and not-for-profit, and unions from broadcasting “electioneering communications.”

Absence of Rights

Corporations lack certain rights that natural persons possess. For example, corporations do not have the privilege against self-incrimination guaranteed for natural persons by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. In any legal proceeding, the courts may force a corporation to turn over incriminating documents, even if they also incriminate officers or employees of the corporation. As we explore in Chapter 18 "Corporate Expansion, State and Federal Regulation of Foreign Corporations, and Corporate Dissolution", corporations are not citizens under the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the Constitution, so that the states can discriminate between domestic and foreign corporations. And the corporation is not entitled to federal review of state criminal convictions, as are many individuals.

Piercing the Corporate Veil

Given the importance of the corporate entity as a veil that limits shareholder liability, it is important to note that in certain circumstances, the courts may reach beyond the wall of protection that divides a corporation from the people or entities that exist behind it. This is known as piercing the corporate veilThe protection of the corporation (the veil) is set aside for litigation purposes, and liability can be imposed on individual shareholders or entities that exist behind the corporation., and it will occur in two instances: (1) when the corporation is used to commit a fraud or an injustice and (2) when the corporation does not act as if it were one.

Fraud

The Felsenthal Company burned to the ground. Its president, one of the company’s largest creditors and also virtually its sole owner, instigated the fire. The corporation sued the insurance company to recover the amount for which it was insured. According to the court in the Felsenthal case, “The general rule of law is that the willful burning of property by a stockholder in a corporation is not a defense against the collection of the insurance by the corporation, and…the corporation cannot be prevented from collecting the insurance because its agents willfully set fire to the property without the participation or authority of the corporation or of all of the stockholders of the corporation.”D. I. Felsenthal Co. v. Northern Assurance Co., Ltd., 284 Ill. 343, 120 N.E. 268 (1918). But because the fire was caused by the beneficial owner of “practically all” the stock, who also “has the absolute management of [the corporation’s] affairs and its property, and is its president,” the court refused to allow the company to recover the insurance money; allowing the company to recover would reward fraud.Felsenthal Co. v. Northern Assurance Co., Ltd., 120 N.E. 268 (Ill. 1918).

Failure to Act as a Corporation

In other limited circumstances, individual stockholders may also be found personally liable. Failure to follow corporate formalities, for example, may subject stockholders to personal liabilityA failure to follow corporate formalities—for example, inadequate capitalization or commingling of assets—can subject stockholders to personal liability.. This is a special risk that small, especially one-person, corporations run. Particular factors that bring this rule into play include inadequate capitalization, omission of regular meetings, failure to record minutes of meetings, failure to file annual reports, and commingling of corporate and personal assets. Where these factors exist, the courts may look through the corporate veil and pluck out the individual stockholder or stockholders to answer for a tort, contract breach, or the like. The classic case is the taxicab operator who incorporates several of his cabs separately and services them through still another corporation. If one of the cabs causes an accident, the corporation is usually “judgment proof” because the corporation will have few assets (practically worthless cab, minimum insurance). The courts frequently permit plaintiffs to proceed against the common owner on the grounds that the particular corporation was inadequately financed.

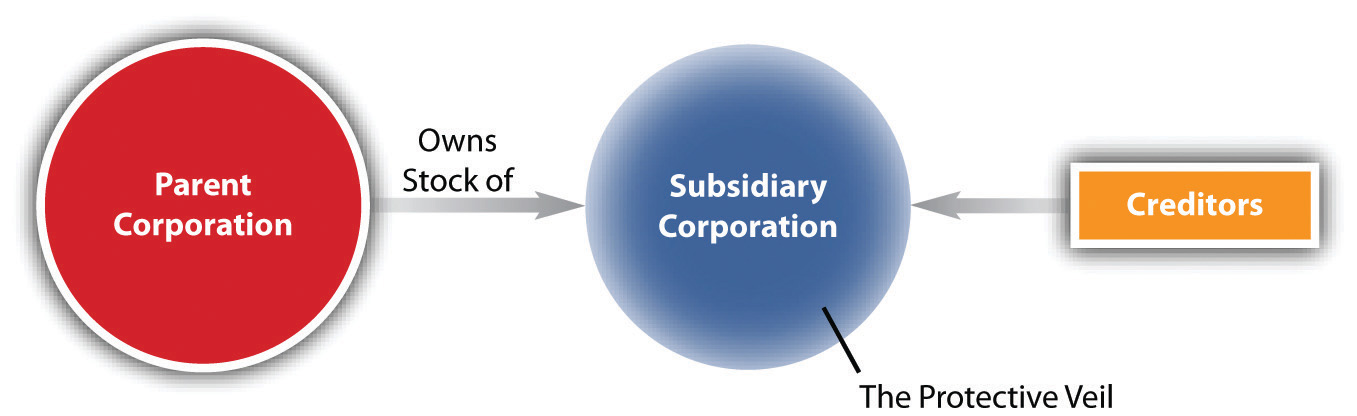

Figure 14.2 The Subsidiary as a Corporate Veil

When a corporation owns a subsidiary corporation, the question frequently arises whether the subsidiary is acting as an independent entity (see Figure 14.2 "The Subsidiary as a Corporate Veil"). The Supreme Court addressed this question of derivative versus direct liability of the corporate parent vis-à-vis its subsidiary in United States v. Bestfoods, (see Section 14.7.2 "Piercing the Corporate Veil").

Other Types of Personal Liability

Even when a corporation is formed for a proper purpose and is operated as a corporation, there are instances in which individual shareholders will be personally liable. For example, if a shareholder involved in company management commits a tort or enters into a contract in a personal capacity, he will remain personally liable for the consequences of his actions. In some states, statutes give employees special rights against shareholders. For example, a New York statute permits employees to recover wages, salaries, and debts owed them by the company from the ten largest shareholders of the corporation. (Shareholders of public companies whose stock is traded on a national exchange or over the counter are exempt.) Likewise, federal law permits the IRS to recover from the “responsible persons” any withholding taxes collected by a corporation but not actually paid over to the US Treasury.

Key Takeaway

Corporations have some of the legal rights of a natural person. They are entitled to the constitutional protections of due process and equal protection, Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable search and seizure, and First Amendment protection of free speech and expression. For purposes of the federal courts’ diversity jurisdiction, a corporation is deemed to be a citizen of both the state in which it is incorporated and the state in which it has its principal place of business. However, corporations do not have the privilege against self-incrimination guaranteed for natural persons by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. Further, corporations are not free from liability. Courts will pierce the corporate veil and hold a corporation liable when the corporation is used to perpetrate fraud or when it fails to act as a corporation.

Exercises

- Do you think that corporations should have rights similar to those of natural persons? Should any of these rights be curtailed?

- What is an example of speaking the “corporate mind”?

- If Corporation BCD’s president and majority stockholder secretly sells all of his stock before resigning a few days later, and the corporation’s unexpected change in majority ownership causes the share price to plummet, do corporate stockholders have a cause of action? If so, under what theory?