This is “The Business Case for Sustainability”, section 1.5 from the book Sustainable Business Cases (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

1.5 The Business Case for Sustainability

Learning Objectives

- Understand the social responsibilities of business.

- Describe the stakeholders in corporations.

- Explain the role of consumers in motivating sustainable business practice.

While the systems perspective is useful as a conceptual framework, there is a need for more practical (and “business-oriented”) guidance on sustainable business practices. A pragmatic approach to sustainable business requires moving away from any extreme position: with one extreme having sustainability as solely an additional cost and the other having that it is always beneficial for business to do more to reduce their environmental and societal impact. Neither is particularly useful to guide business practices.

The framing of corporations and their role in society strongly affects the case for and practice of sustainable business. And there are many views of the corporation and private companies and their role/place in a private market economy.

The Nobel Prize–winning economist Milton Friedman from the University of Chicago’s School of Economics wrote about the social responsibility of business. He described business responsibility as being the achievement of profit in a legal manner. For Friedman, “There is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition, without deception or fraud.”J. DesJardins, “Corporate Environmental Responsibility,” Journal of Business Ethics 17, no. 8 (1998).

Working from Friedman’s perspective businesses should only engage in sustainable business practices if the practices can directly contribute to their own economic bottom line or if government mandated that business engage in sustainable practices—that is, it was illegal not to do it. Friedman questioned the logic of corporate social responsibility as it had been developing at the time. He insisted that in a democratic society, government, not business, was the only legitimate vehicle for addressing social concerns. He argued that government was the best vehicle for meeting societal concerns, such as environmental sustainability, but many found it difficult to believe, given Friedman’s libertarianism, that such an argument was in good faith.

The response of management thinkers to Friedman was to develop alternative views of corporate social responsibility (CSR)A business model where societal impact is considered in business decision making. It shifts the focus from only considering the financial impact on the company when making decisions to including societal and environmental impacts. This business model shares many similarities to the business model of sustainability for companies.. Two are presented as follows: the view of stakeholder management and the model of global corporate citizenship, respectively. While there are relevant differences in these, they share important common ground.

StakeholderAny person, group, or organization affected by an organization’s actions. For businesses, it can include owners and investors, employees, customers, suppliers, and all members of society affected by the organization. engagement is a formal process of relationship management through which companies or industries engage with a set of their stakeholders in an effort to align and advance their mutual interests. This often involves different stakeholders, such as owners, employees and customers, identifying what is in their collective interest. For example, for BP in the future to practice more effective forms of environmental risk management and for Google to invest in renewable energy innovation.

Corporate citizenship involves corporate management focusing on the net contribution that a company makes through its core business activities, its social investment and philanthropy programs, and its engagement in public policy to society and a broad set of stakeholders. That contribution is determined by the manner in which a company manages its economic, social and environmental impacts and manages its relationships with different stakeholders, in particular shareholders, employees, customers, business partners, governments, communities and future generations.

The relationship of the models of corporate social responsibility to sustainability is reflected in the values statement of Johnson & Johnson, a company with a strong reputation for corporate citizenship. (Note the “corporate citizenship, or sustainability.”)

We see corporate citizenship, or sustainability, not as a set of “add-ons” to our business but rather as intrinsic to everything we do. We’ve long recognized that the sustainability of our business depends on being attuned to society’s expectations across many domains—including the environment, access to medicines, advocacy, governance and compliance."Sustainability Report 2008,” Johnson & Johnson, http://www.jnj.com/wps/wcm/connect/ad9170804f55661a9ec3be1bb31559c7/2008+Sustainability+Report.pdf?MOD=AJPERES.

CSR covers the responsibilities corporations have to a broad set of stakeholders, including the communities within which they are based and operate. More specifically, CSR for many management scholars involves a business identifying its key stakeholder groups and incorporating their needs and values within the business’s strategic, day-to-day decision-making process.M. Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom (University of Chicago Press, 1962). The stakeholders in corporations and any private company include owners and investors, employees, consumers, and all those affected by the actions of the corporation.

A key stakeholder group relevant to sustainable business practices is consumers. The environmental movement in the United States was ignited in the 1970s as an increasing percentage of consumers began to understand that the environment was at risk. Information about this was enhanced with the 1972 publication of Limits to Growth, a research study by the MIT Systems Lab and released by the Club of Rome. The book explained the results of computer models that predicted when the world would run out of certain resources. The study presented what was for many at the time a novel finding that the earth’s resources were finite.

Thirty years after the Limits of Growth was published, public interest and concern for the environment was raised to another level with the emergence of increased scientific evidence of global warming and the human contribution to global warming and the presentation to the general public of the evidence by former US vice president Al Gore in the 2006 movie An Inconvenient Truth. The release of the movie was at the same time as the George W. Bush administration was resisting pressure to move forward on federal policy to address global warming (see Chapter 2 "The Science of Sustainability" and Chapter 3 "Government, Public Policy, and Sustainable Business").

Increasing numbers of people in the United States and elsewhere turned to business as both the problem and the solution to global warming. Research findings had heightened recognition of businesses as major users of societal resources and major contributors to environmental problems. And with that, there was increased pressure on businesses to be part of the solution to global warming.

Consumers played a very significant role in raising businesses’ interest in sustainability. Consumers can use the market (i.e., their purchases) to send a signal to businesses about their concern for the environment and sustainability. Each and every consumer’s decision to purchase or not purchase from a company based on the business entities’ environmental or sustainability practices directly impacts a company’s bottom line. In this way, consumers can be, and increasingly are, a very powerful external force that can motivate companies to become more sustainable in their practices (see Chapter 6 "Sustainable Business Marketing").

The power of consumers and also the opportunity for corporations to influence consumer demand to benefit their sales is reflected in the corporate statement of Green Mountain Coffee as follows (see Chapter 9 "Case: Brewing a Better World: Sustainable Supply Chain Management at Green Mountain Coffee Roasters, Inc."):

We’re focusing on building demand for sustainable products and evolving our product line to be more sustainable. Once consumers understand the goals of Fair Trade and sustainability—protecting scarce resources, strengthening communities, reducing poverty, and ensuring equity in commercial relationships—they will want to help build a better world.

A new group of environmentally responsible consumers has emerged. They are the lead adopters and others are following. These consumers take into account a variety of factors before they choose to support a company by buying their product. They consider the impact of materials and processes used to manufacture and package goods, how products are distributed and disposed of, a company’s broader corporate philosophy on the environment, and even a company’s support of public environmental education programs. These factors, among many others, are becoming increasingly important to consumers and consequently to the companies themselves.

According to a 2006 Mintel Research study, the so-called green marketplace was estimated at somewhere between $300 billion to $500 billion a year. And all indications are that it has grown significantly since then. The same study showed that there were approximately thirty-five million Americans who regularly bought green products and that 77 percent of consumers changed their purchasing habits due to a company’s green image. Marketing statistics from many different industries support this. Green homes, for example, are estimated to cost between 2 percent to 5 percent more to construct but are valued at 10 percent to 15 percent more in the marketplace. Likewise, organic dairy products are priced typically 15 percent to 20 percent more than conventional ones, and organic meats are often priced two to three times more than traditional meat.Jay Hasbrouck and Allison Woodruff, “Green Homeowners as Lead Adopters,” Intel Technology Journal 12, no. 1 (2008): 42.

Many companies that have already incorporated sustainability into their business have received benefits in the form of reduced energy and other costs, increased consumer demand, and improved market share. But despite the growing trend of “green purchasing,” approximately one-quarter of Americans still do not consciously purchase goods based on a company’s sustainability efforts. There is an even larger segment of Americans (approximately 50 percent) that express some level of concern for the environment but may not have the knowledge or commitment required to purchase goods based on a business’s efforts in sustainability.

Environmental organizations have responded to this lack of information by providing consumers with resources to make environmentally responsible buying decisions. For example, Climate Counts (http://www.climatecounts.org/scorecard_overview.php) is a nonprofit organization that evaluates, with numerical scores, more than 140 major corporations on their efforts to reverse climate change. Climate Counts publishes these scores so that consumers may use them to support those companies that are showing serious commitment to the environment. The companies are scored on a scale from zero to one hundred based on twenty-two criteria to determine whether a company has

- measured its climate impact,

- reduced its impact on climate change,

- supported (or blocked) progressive climate legislation,

- publicly disclosed its climate actions in a clear and comprehensive format.

In Climate Counts’s Winter/Spring 2010 edition of their scorecard, scores ranged from zero to a high of eighty-three. Climate Counts works extensively to educate consumers on corporate sustainability and to encourage them to support companies with scores as close to one hundred as possible.

While Climate Counts focuses on larger corporations, organizations such as the Green Alliance in New Hampshire (http://www.greenalliance.biz) address local companies and their efforts to incorporate sustainability into their business. Based in the Seacoast region of New Hampshire, Green Alliance represents one of the many organizations that spur environmentally responsible purchasing on a local level. Similar to Climate Counts, Green Alliance scores companies to direct consumers to the most sustainable buying options. Similar types of organizations are located in communities across the country and have affected the sustainable business practices of private companies.

Apart from the stakeholder-driven perspective of CSR, another important concept of CSR is the notion of companies looking beyond profits to their role in society. It refers to a company linking itself with ethical values, transparency, employee relations, compliance with legal requirements, and overall respect for the communities in which they operate. With this perspective, CSR moves closer to the sustainable business perspective, as the focus includes managing the impact businesses have on the environment and society.

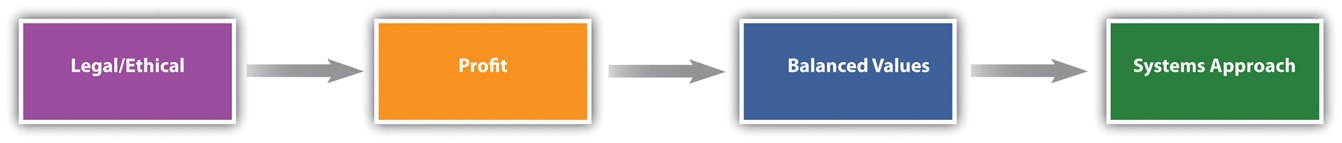

A path for businesses to adopt sustainable business practices might be thought of as a continuum (see as follows).

- It can start with Friedman’s perspective that businesses adopt sustainable practices because it is a legal obligation—governmental laws and regulations require it.

- It can include, also from Friedman, the pure profit-driven motive—businesses adopt sustainable practices because they clearly contribute to corporate profits; for example, it can contribute to brand name recognition and sales. With this motive there is little systematic search for opportunities or embedding of sustainable practices in business.

- It can include a balanced values-based approach in which businesses adopt sustainable business practices from a search for a balanced solution to optimize economic performance and societal benefits.

- It can include a systems approach. Sustainable business practices are fully embedded into every aspect of the business. Businesses have an understanding of the interconnectivity of their business to society over time and act on it. The focus is on the sustainability of all critical aspects of the system and the influence of the private company on these elements. Business sustainability is valued along with sustainability of environmental, social, and human resource elements in the system.

Key Takeaways

- There are many views of the corporation and private companies and their role or place in a private market economy.

- For economist Milton Friedman, there is one and only one social responsibility of business beyond adhering to society’s laws and that is to use its resources and engage in activities to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game.

- Others view the social responsibility of business to include concern for various stakeholders and for the morality and ethics of their practices and their impact on stakeholders.

- For businesses looking to become more sustainable, it can be thought of as a continuum between legal and ethical actions up to a systems perspective.

Exercises

- Do you agree with Milton Friedman’s profit-driven philosophy that the purpose of business is to earn a profit and that should be the sole focus of business, with government being responsible for social and environmental issues? Why or why not?

- Search the web for an article that provides an example of a business that implemented a social or environmental practice that had negative economic impact on the company. Search the web for an article that provides an example of the business that implemented a social environment of practice that had a positive economic impact on the company. Why do you feel the company with a practice that has a negative impact on the company experienced that result? Based on these two articles, do you think that companies should be concerned with sustainability?

- It can be challenging to think of operating a business with a systems perspective. Think of one example of a sustainability practice that incorporates elements of a systems perspective. Describe the internal and external environment and the linkages between the two and what healthy practices meet the criteria of being considered sustainable.