This is “Race and Ethnicity”, chapter 10 from the book Sociology: Comprehensive Edition (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 10 Race and Ethnicity

Social Issues in the News

“White Supremacist Held Without Bond in Tuesday’s Attack,” the headline said. James Privott, a 76-year-old African American, had just finished fishing in a Baltimore city park when he was attacked by several white men. They knocked him to the ground, punched him in the face, and hit him with a baseball bat. Privott lost two teeth and had an eye socket fractured in the assault. One of his assailants was arrested soon afterwards and told police the attack “wouldn’t have happened if he was a white man.” The suspect was a member of a white supremacist group, had a tattoo of Hitler on his stomach, and used “Hitler” as his nickname. At a press conference attended by civil rights and religious leaders, the Baltimore mayor denounced the hate crime. “We all have to speak out and speak up and say this is not acceptable in our communities,” she said. “We must stand together in opposing this kind of act.” (Fenton, 2009, p. 11)Fenton, J. (2009, August 20). Details emerge on suspect: White supremacist held without bail in Tuesday’s attack at Fort Armistead Park. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved from http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/baltimore-city/bal-md.ci.lockner20aug20,20,1843383.story

In 1959, John Howard Griffin, a white writer, changed his race. Griffin decided that he could not begin to understand the discrimination and prejudice that African Americans face every day unless he experienced these problems himself. So he went to a dermatologist in New Orleans and obtained a prescription for an oral medication to darken his skin. The dermatologist also told him to lie under a sunlamp several hours a day and to use a skin-staining pigment to darken any light spots that remained.

Griffin stayed inside, followed the doctor’s instructions, and shaved his head to remove his straight hair. About a week later he looked, for all intents and purposes, like an African American. Then he went out in public and passed as black.

New Orleans was a segregated city in those days, and Griffin immediately found he could no longer do the same things he did when he was white. He could no longer drink at the same water fountains, use the same public restrooms, or eat at the same restaurants. When he went to look at a menu displayed in the window of a fancy restaurant, he later wrote,

I read, realizing that a few days earlier I could have gone in and ordered anything on the menu. But now, though I was the same person with the same appetite, no power on earth could get me inside this place for a meal. (Griffin, 1961, p. 42)Griffin, J. H. (1961). Black like me. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

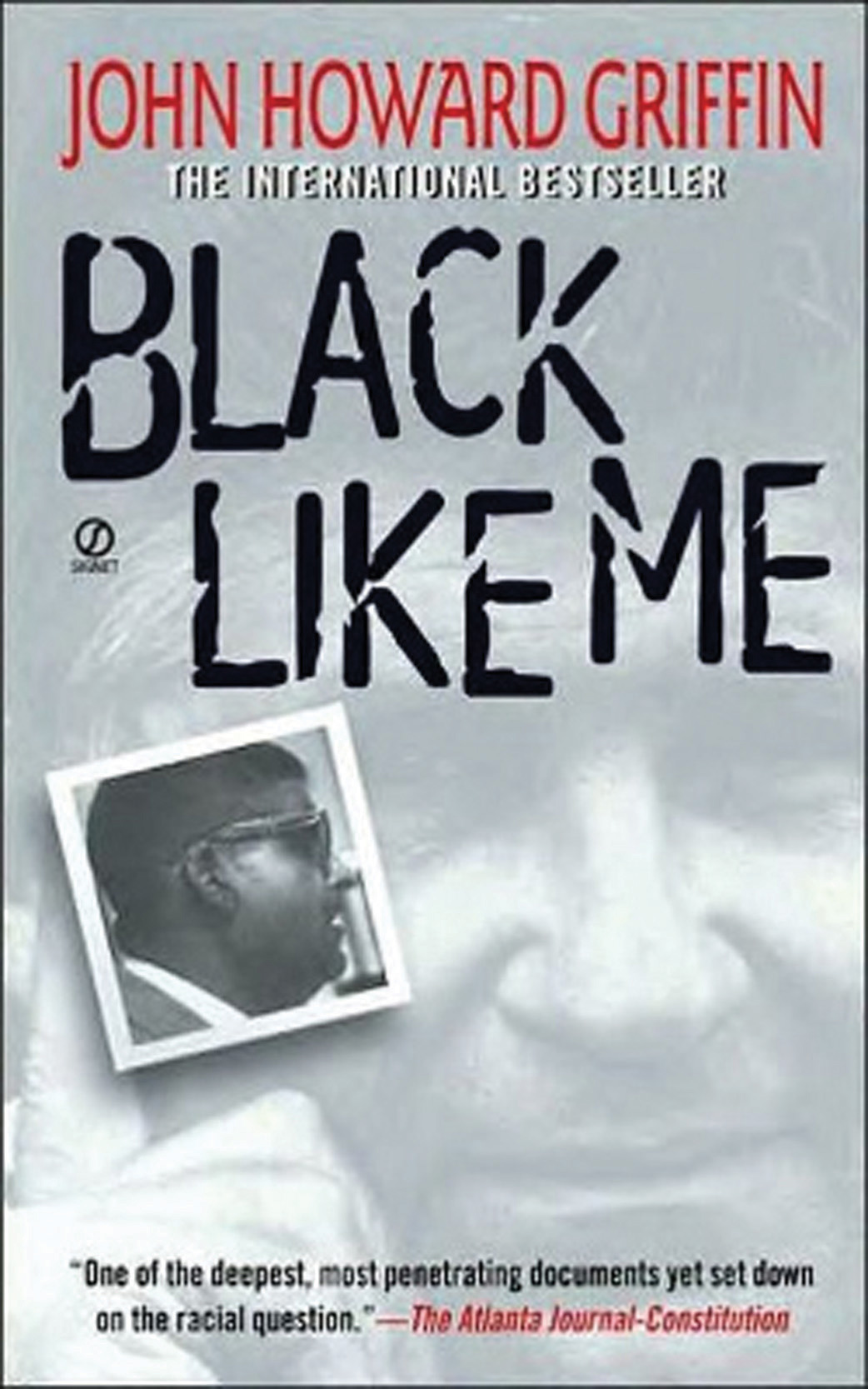

John Howard Griffin’s classic 1959 book Black Like Me documented the racial discrimination he experienced in the South after darkening his skin and passing as black.

Because of his new appearance, Griffin suffered other slights and indignities. Once when he went to sit on a bench in a public park, a white man told him to leave. Later a white bus driver refused to let Griffin get off at his stop and let him off only eight blocks later. A series of stores refused to cash his traveler’s checks. As he traveled by bus from one state to another, he was not allowed to wait inside the bus stations. At times white men of various ages cursed and threatened him, and he became afraid for his life and safety. Months later, after he wrote about his experience, he was hanged in effigy, and his family was forced to move from their home.

Griffin’s reports about how he was treated while posing as a black man, and about the way African Americans he met during that time were also treated, helped awaken white Americans across the United States to racial prejudice and discrimination. The Southern civil rights movement, which had begun a few years earlier and then exploded into the national consciousness with sit-ins at lunch counters in February 1960 by black college students in Greensboro, North Carolina, ended Southern segregation and changed life in the South and across the rest of the nation.

What has happened since then? Where do we stand more than 50 years after the beginning of the civil rights movement and Griffin’s travels in the South? In answering this question, this chapter discusses the changing nature of racial and ethnic prejudice and inequality in the United States but also documents their continuing importance for American society, as the hate crime story that began this chapter signifies. We begin our discussion of the present with a brief look back to the past.