This is “Social Change: Population, Urbanization, and Social Movements”, chapter 14 from the book Sociology: Brief Edition (v. 1.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 14 Social Change: Population, Urbanization, and Social Movements

Social Issues in the News

“Governor Signs Texting Law Inspired by Teen’s Death,” the headline said. In June 2010, the governor of Georgia signed the Caleb Sorohan Act, named for an 18-year-old student who died in a car accident caused by his texting while driving. The bill made it illegal for any drivers in Georgia to text unless they were parked. After Caleb died, his family started a campaign, along with dozens of his high school classmates, to enact a texting while driving ban. They signed petitions, started a Facebook page, and used phone banks to lobby members of their state legislature. Vermont enacted a similar ban about the same time. The new laws in Georgia and Vermont increased the number of states banning texting while driving to 28. (Downey, 2010)Downey, M. (2010, June 4). Governor signs texting law inspired by teen’s death. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved from http://blogs.ajc.com/get-schooled-blog/2010/06/04/governor-signs-texting-law-inspired-by-teens-death

“Amherst Sleeps Out to Protest Climate Change,” another headline said. It was February 2010, and a student at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, had been living in a tent for 121 days. His goal was to call attention to the importance of clean energy. The student was a member of a Massachusetts group, Students for a Just and Stable Future (SJSF), comprised of college students across the state. To dramatize the problem of climate change, the group had engaged in sleep-outs in various parts of the state, including one on the Boston Common, a famed public park in that city, over a series of weekends in late 2009. About 200 students were arrested on trespassing charges for staying in the park after it was closed at 11:00 p.m. The UMass student in the tent thought he was making a difference; as he put it, “Hopefully people see me and realize that there are people out there who care about the Earth’s future and civilization’s stability enough to do something about it.” Yet he knew that improvements to the environment would take some time: “It’s not going to happen overnight.” (Vincent, 2010, p. A16)Vincent, L. (2010). Amherst sleeps out to protest climate change. DailyCollegian.com. Retrieved from http://dailycollegian.com/2010/2002/2021/amherst-sleeps-out-to-protest-climate-change

Societies change just as people do. The change we see in people is often very obvious, as when they have a growth spurt during adolescence, lose weight on a diet, or buy new clothes or get a new hairstyle. The change we see in society is usually more gradual. Unless it is from a natural disaster like an earthquake or from a political revolution, social change is usually noticeable only months or years after it began. This sort of social change arises from many sources: changes in a society’s technology (as the news story on texting and driving illustrates), in the size and composition of its population, and in its culture. But some social change stems from the concerted efforts of people acting in social movements to alter social policy, as the news story on the student in the tent illustrates, or even the very structure of their government.

This chapter examines the types and sources of social change. We begin by looking generally at social change to understand its overall significance. We then turn to the study of population, as changes in population can and do have important implications for changes in society itself. We also look at urbanization, which over the centuries has changed the social landscape profoundly. Finally, we look at social movements, which involve purposive efforts by groups of people to bring about changes they think necessary and desirable in society.

14.1 Understanding Social Change

Learning Objectives

- Understand the differences between modern, large societies and small, traditional societies.

- Discuss the functionalist and conflict perspectives on social change.

- Describe the major sources of social change.

Social changeThe transformation of culture (especially norms and values), behavior, social institutions, and social structure over time. refers to the transformation of culture, behavior, social institutions, and social structure over time. We are familiar from earlier chapters with the basic types of society: hunting and gathering, horticultural and pastoral, agricultural, industrial, and postindustrial. In looking at all of these societies, we have seen how they differ in such dimensions as size, technology, economy, inequality, and gender roles. In short, we have seen some of the ways in which societies change over time. Another way of saying this is that we have seen some of the ways in which societies change as they become more modern. To understand social change, then, we need to begin to understand what it means for a society to become more modern. We considered this briefly in Chapter 2 "Culture and Society" and expand on it here.

Modernization

ModernizationThe process and impact of becoming more modern. refers to the process and impact of becoming more modern. Modernization has been an important focus of sociology since its origins in the 19th century. Several dimensions and effects of modernization seem apparent (Nolan & Lenski, 2009).Nolan, P., & Lenski, G. (2009). Human societies: An introduction to macrosociology (11th ed.). Boulder, CO: Paradigm.

First, as societies evolve, they become much larger and more heterogeneous. This means that people are more different from each other than when societies were much smaller, and it also means that they ordinarily cannot know each other nearly as well. Larger, more modern societies thus typically have weaker social bonds and a weaker sense of community than small societies and more of an emphasis on the needs of the individual.

Figure 14.1

As societies become more modern, they begin to differ from nonmodern societies in several ways. In particular, they become larger and more heterogeneous, they lose their traditional ways of thinking, and they gain in individual freedom and autonomy.

© Thinkstock

We can begin to appreciate the differences between smaller and larger societies when we contrast a small college of 1,200 students with a large university of 40,000 students. Perhaps you had this contrast in mind when you were applying to college and had a preference for either a small or a large institution. In a small college, classes might average no more than 20 students; these students get to know each other well and to have a lot of interaction with the professor. In a large university, classes might hold 600 students or more, and everything is more impersonal. Large universities do have many advantages, but they probably do not have as strong a sense of community as is found at small colleges.

A second aspect of modernization is a loss of traditional ways of thinking. This allows a society to be creative and to abandon old ways that may no longer be appropriate, but it also means a weakening or even loss of the traditions that helped define the society and gave it a sense of identity.

A third aspect of modernization is the growth of individual freedom and autonomy. As societies grow, become more impersonal, and lose their traditions and sense of community, their norms become weaker, and individuals thus become freer to think for themselves and to behave in new ways. Although most of us would applaud this growth in individual freedom, it also means, as Émile Durkheim (1895/1962)Durkheim, E. (1962). The rules of sociological method. New York, NY: Free Press. (Original work published 1895) recognized long ago, that people feel freer to deviate from society’s norms and thus to commit deviance. If we want a society that values individual freedom, Durkheim said, we automatically must have a society with deviance.

Is modernization good or bad? This is a simplistic question about a very complex concept, but a quick answer is that it is both good and bad. We see evidence for both responses in the views of sociologists Ferdinand Tönnies, Max Weber, and Durkheim. As Chapter 2 "Culture and Society" discussed, Tönnies (1887/1963)Tönnies, F. (1963). Community and society. New York, NY: Harper and Row. (Original work published 1887) said that modernization meant a shift from Gemeinschaft (small societies with strong social bonds) to Gesellschaft (large societies with weaker social bonds and more impersonal social relations). Tönnies lamented the loss of close social bonds and of a strong sense of community resulting from modernization.

Weber (1921/1978)Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology (G. Roth & C. Wittich, Eds.). Berkeley: University of California Press. (Original work published 1921) was also concerned about modernization. The hallmarks of modernization, he thought, are rationalization, a loss of tradition, and the rise of impersonal bureaucracy. He despaired over the impersonal quality of rational thinking and bureaucratization, as he thought it was a dehumanizing influence.

Durkheim (1893/1933)Durkheim, E. (1933). The division of labor in society. London, England: The Free Press. (Original work published 1893) took a less negative view of modernization. He certainly appreciated the social bonds and community feeling, which he called mechanical solidarityÉmile Durkheim’s conception of the type of social bonds and community feeling in small, traditional societies resulting from their homogeneity., characteristic of small, traditional societies. However, he also thought that these societies stifled individual freedom and that social solidarity still exists in modern societies. This solidarity, which he termed organic solidarityÉmile Durkheim’s conception of the type of social bonds and community feeling in large, modern societies resulting from their division of labor and interdependence of roles., stems from the division of labor, in which everyone has to depend on everyone else to perform their jobs. This interdependence of roles, Durkheim said, creates a solidarity that retains much of the bonding and sense of community found in premodern societies.

Beyond these abstract concepts of social bonding and sense of community, modern societies have certainly been a force for both good and bad in other ways. They have led to scientific discoveries that have saved lives, extended life spans, and made human existence much easier than imaginable in the distant past and even in the recent past. But they have also polluted the environment, engaged in wars that have killed tens of millions, and built up nuclear arsenals that, even with the demise of the Soviet Union, still threaten the planet. Modernization, then, is a double-edged sword. It has given us benefits too numerous to count, but it also has made human existence very precarious.

Sociological Perspectives on Social Change

Sociological perspectives on social change fall into the functionalist and conflict approaches. As usual, both views together offer a more complete understanding of social change than either view by itself (Vago, 2004).Vago, S. (2004). Social change (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Table 14.1 "Theory Snapshot" summarizes their major assumptions.

Table 14.1 Theory Snapshot

| Theoretical perspective | Major assumptions |

|---|---|

| Functionalism | Society is in a natural state of equilibrium. Gradual change is necessary and desirable and typically stems from such things as population growth, technological advances, and interaction with other societies that brings new ways of thinking and acting. However, sudden social change is undesirable because it disrupts this equilibrium. To prevent this from happening, other parts of society must make appropriate adjustments if one part of society sees too sudden a change. |

| Conflict theory | Because the status quo is characterized by social inequality and other problems, sudden social change in the form of protest or revolution is both desirable and necessary to reduce or eliminate social inequality and to address other social ills. |

The Functionalist Understanding

The functionalist understanding of social change is based on insights developed by different generations of sociologists. Early sociologists likened change in society to change in biological organisms. Taking a cue from the work of Charles Darwin, they said that societies evolved just as organisms do, from tiny, simple forms to much larger and more complex structures. When societies are small and simple, there are few roles to perform, and just about everyone can perform all of these roles. As societies grow and evolve, many new roles develop, and not everyone has the time or skill to perform every role. People thus start to specialize their roles and a division of labor begins. As noted earlier, sociologists such as Durkheim and Tönnies disputed the implications of this process for social bonding and a sense of community, and this basic debate continues today.

Several decades ago, Talcott Parsons (1966),Parsons, T. (1966). Societies: Evolutionary and comparative perspectives. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. the leading 20th-century figure in functionalist theory, presented an equilibrium modelTalcott Parsons’s functionalist view that society’s balance is disturbed by sudden social change. of social change. Parsons said that society is always in a natural state of equilibrium, defined as a state of equal balance among opposing forces. Gradual change is both necessary and desirable and typically stems from such things as population growth, technological advances, and interaction with other societies that brings new ways of thinking and acting. However, any sudden social change disrupts this equilibrium. To prevent this from happening, other parts of society must make appropriate adjustments if one part of society sees too sudden a change.

Figure 14.2

Functionalist theory assumes that sudden social change, as by the protest depicted here, is highly undesirable, whereas conflict theory assumes that sudden social change may be needed to correct inequality and other deficiencies in the status quo.

Source: Photo courtesy of Kashfi Halford, http://www.flickr.com/photos/kashklick/3406972544.

The functionalist perspective has been criticized on a few grounds. The perspective generally assumes that the change from simple to complex societies has been very positive, when in fact, as we have seen, this change has also proven costly in many ways. It might well have weakened social bonds, and it has certainly imperiled human existence. Functionalist theory also assumes that sudden social change is highly undesirable, when such change may in fact be needed to correct inequality and other deficiencies in the status quo.

Conflict Theory

Whereas functional theory assumes the status quo is generally good and sudden social change is undesirable, conflict theory assumes the status quo is generally bad. It thus views sudden social change in the form of protest or revolution as both desirable and necessary to reduce or eliminate social inequality and to address other social ills. Another difference between the two approaches concerns industrialization, which functional theory views as a positive development that helped make modern society possible. In contrast, conflict theory, following the views of Karl Marx, says that industrialization exploited workers and thus increased social inequality.

In one other difference between the two approaches, functionalist sociologists view social change as the result of certain natural forces, which we will discuss shortly. In this sense, social change is unplanned even though it happens anyway. Conflict theorists, however, recognize that social change often stems from efforts by social movements to bring about fundamental changes in the social, economic, and political systems. In his sense social change is more “planned,” or at least intended, than functional theory acknowledges.

Critics of conflict theory say that it exaggerates the extent of social inequality and that it sometimes overemphasizes economic conflict while neglecting conflict rooted in race and ethnicity, gender, religion, and other sources. Its Marxian version also erred in predicting that capitalist societies would inevitably undergo a socialist-communist revolution.

Sources of Social Change

We have seen that social change stems from natural forces and also from the intentional acts of groups of people. This section further examines these sources of social change.

Population Growth and Composition

Much of the discussion so far has talked about population growth as a major source of social change as societies evolved from older to modern times. Yet even in modern societies, changes in the size and composition of the population can have important effects for other aspects of a society. As just one example, the number of school-age children reached a high point in the late 1990s as the children of the post–World War II baby boom entered their school years. This swelling of the school-age population had at least three important consequences. First, new schools had to be built, modular classrooms and other structures had to be added to existing schools, and more teachers and other school personnel had to be hired (Leonard, 1998).Leonard, J. (1998, September 25). Crowding puts crunch on classrooms. The Los Angeles Times, p. B1. Second, school boards and municipalities had to borrow dollars and/or raise taxes to pay for all of these expenses. Third, the construction industry, building supply centers, and other businesses profited from the building of new schools and related activities. The growth of this segment of our population thus had profound implications for many aspects of U.S. society even though it was unplanned and “natural.” We explore population growth and change further in a later section.

Culture and Technology

Culture and technology are other sources of social change. Changes in culture can change technology; changes in technology can transform culture; and changes in both can alter other aspects of society (Crowley & Heyer, 2011).Crowley, D., & Heyer, P. (2011). Communication in history: Technology, culture, society (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Two examples from either end of the 20th century illustrate the complex relationship among culture, technology, and society. At the beginning of the century, the car was still a new invention, and automobiles slowly but surely grew in number, diversity, speed, and power. The car altered the social and physical landscape of the United States and other industrial nations as few other inventions have. Roads and highways were built; pollution increased; families began living farther from each other and from their workplaces; tens of thousands of people started dying annually in car accidents. These are just a few of the effects the invention of the car had, but they illustrate how changes in technology can affect so many other aspects of society.

At the end of the 20th century came the personal computer, whose development has also had an enormous impact that will not be fully understand for some years to come. Anyone old enough, such as many of your oldest professors, to remember having to type long manuscripts on a manual typewriter will easily attest to the difference computers have made for many aspects of our work lives. E-mail, the Internet, and smartphones have enabled instant communication and make the world a very small place, and tens of millions of people now use Facebook and other social media. A generation ago, students studying abroad or working in the Peace Corps overseas would send a letter back home, and it would take up to 2 weeks or more to arrive. It would take another week or 2 for them to hear back from their parents. Now even in poor parts of the world, access to computers and smartphones lets us communicate instantly with people across the planet.

As the world becomes a smaller place, it becomes possible for different cultures to have more contact with each other. This contact, too, leads to social change to the extent that one culture adopts some of the norms, values, and other aspects of another culture. Anyone visiting a poor nation and seeing Coke, Pepsi, and other popular U.S. products in vending machines and stores in various cities will have a culture shock that reminds us instantly of the influence of one culture on another. For better or worse, this impact means that the world’s diverse cultures are increasingly giving way to a more uniform global culture.

This process has been happening for more than a century. The rise of newspapers, the development of trains and railroads, and the invention of the telegraph, telephone, and, later, radio and television allowed cultures in different parts of the world to communicate with each other in ways not previously possible. Affordable jet transportation, cell phones, the Internet, and other modern technology have taken such communication a gigantic step further.

Many observers fear that the world is becoming “Westernized” as Coke, Pepsi, McDonald’s, and other products and companies invade other cultures. Others say that Westernization is a good thing, because these products, but especially more important ones like refrigerators and computers, do make people’s lives easier and therefore better. Still other observers say the impact of Westernization has been exaggerated. Both within the United States and across the world, these observers say, many cultures continue to thrive, and people continue to hold on to their ethnic identities.

The Natural Environment

Figure 14.3

As is evident in this photo taken in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake that devastated Haiti, changes in the natural environment can lead to profound changes in a society. Environmental changes are one of the many sources of social change.

Source: Photo courtesy of United Nations, http://www.flickr.com/photos/37913760@N03/4274632760.

Changes in the natural environment can also lead to changes in a society itself. We see the clearest evidence of this when a major hurricane, an earthquake, or another natural disaster strikes. Three recent disasters illustrate this phenomenon. In April 2010, an oil rig operated by BP, an international oil and energy company, exploded in the Gulf of Mexico, creating the worst environmental disaster in U.S. history; its effects on the ocean, marine animals, and the economies of states and cities affected by the oil spill will be felt for decades to come. In January 2010, a devastating earthquake struck Haiti and killed more than 250,000 people, or about 2.5% of that nation’s population. A month later, an even stronger earthquake hit Chile. Although this earthquake killed only hundreds (it was relatively far from Chile’s large cities and the Chilean buildings were sturdily built), it still caused massive damage to the nation’s infrastructure. Obviously the effects of these natural disasters on the economy and society of each of these two countries will also be felt for many years to come.

Slower changes in the environment can also have a large social impact. As noted earlier, one of the negative effects of industrialization has been the increase in pollution of our air, water, and ground. With estimates of the number of U.S. deaths from air pollution ranging from a low of 10,000 to a high of 60,000 (Reiman & Leighton, 2010),Reiman, J., & Leighton, P. (2010). The rich get richer and the poor get prison: Ideology, class, and criminal justice (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pollution obviously has an important impact on our society. A larger environmental problem, climate change, has also been relatively slow in arriving but threatens the whole planet in ways that climate change researchers have already documented and will no doubt be examining for the rest of our lifetimes and beyond (Schneider, Rosencranz, Mastrandrea, & Kuntz-Duriseti, 2010).Schneider, S. H., Rosencranz, A., Mastrandrea, M. D., & Kuntz-Duriseti, K. (Eds.). (2010). Climate change science and policy. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Social Conflict

Change also results from social conflict, including wars, ethnic conflict, efforts by social movements to change society, and efforts by their opponents to maintain the status quo. The immediate impact that wars have on societies is obvious, as the deaths of countless numbers of soldiers and civilians over the ages have affected not only the lives of their loved ones but also the course of whole nations. To take just one of many examples, the defeat of Germany in World War I led to a worsening economy during the next decade that in turn helped fuel the rise of Hitler. In a less familiar example, the deaths of so many soldiers during the American Civil War left many wives and mothers without their family’s major breadwinner. Many of these women thus had to turn to prostitution to earn an income, helping to fuel a rise in prostitution after the war (Marks, 1990).Marks, P. (1990). Bicycles, bangs, and bloomers: The new woman in the popular press. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

Social movements have also been major forces for social change. Racial segregation in the South ended only after thousands of African Americans, often putting their lives on the line for their cause, engaged in sit-ins, marches, and massive demonstrations during the 1950s and 1960s. The Southern civil rights movement is just one of the many social movements that have changed American history, and we return to these movements later in the chapter.

Key Takeaways

- As societies become more modern, they become larger and more heterogeneous. Traditional ways of thinking decline, and individual freedom and autonomy increase.

- Functionalist theory favors slow, incremental social change, while conflict theory favors fast, far-reaching social change to correct what it views as social inequalities and other problems in the status quo.

- Major sources of social change include population growth and composition, culture and technology, the natural environment, and social conflict.

For Your Review

- If you had to do it over again, would you go to a large university, a small college, or something in between? Why? How does your response relate to some of the differences between smaller, traditional societies and larger, modern societies?

- When you think about today’s society and social change, do you favor the functionalist or conflict view on the kind of social change that is needed? Explain your answer.

14.2 Population

Learning Objectives

- Explain why there is less concern about population growth now than there was a generation ago.

- Describe how demographers measure birth and death rates.

- Understand demographic transition theory and how it compares with the views of Malthus.

We have commented that population growth is an important source of other changes in society. A generation ago, population growth was a major issue in the United States and some other nations. Zero population growth, or ZPG, was a slogan often heard. There was much concern over the rapidly growing population in the United States and, especially, around the world, and there was fear that our “small planet” could not support massive increases in the number of people (Ehrlich, 1969).Ehrlich, P. R. (1969). The population bomb. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club. Some of the most dire predictions of the time warned of serious food shortages by the end of the century.

Those predictions did not come to pass, and concern over population growth has faded as the world’s resources seem to be standing up to population growth. Widespread hunger in Africa and other regions does exist, with hundreds of millions of people suffering from hunger and malnutrition, but many experts attribute this problem not to overpopulation and lack of food but rather to problems in distributing the sufficient amount of food that actually does exist to people in poor nations (see “Sociology Making a Difference” box).

Sociology Making a Difference

World Hunger and the Scarcity Fallacy

A popular belief is that world hunger exists because there is too little food to feed too many people in poor nations in Africa, Asia, and elsewhere. Sociologists Stephen J. Scanlan, J. Craig Jenkins, and Lindsey Peterson (2010)Scanlan, S. J., Jenkins, J. C., & Peterson, L. (2010). The scarcity fallacy. Contexts, 9(1), 34–39. call this belief the “scarcity fallacy.” According to these authors, “The conventional wisdom is that world hunger exists primarily because of natural disasters, population pressure, and shortfalls in food production” (p. 35). However, this conventional wisdom is mistaken, as world hunger stems not from a shortage of food but from the inability to deliver what is actually a sufficient amount of food to the world’s poor. As Scanlan and colleagues note,

A good deal of thinking and research in sociology suggests that world hunger has less to do with the shortage of food than with a shortage of affordable or accessible food. Sociologists have found that social inequalities, distribution systems, and other economic and political factors create barriers to food access. (p. 35)

This sociological view has important implications for how the world should try to reduce global hunger, say these authors. International organizations such as the World Bank and several United Nations agencies have long believed that hunger is due to food scarcity, and this belief underlies the typical approaches to reducing world hunger that focus on increasing food supplies with new technologies and developing more efficient methods of delivering food. But if food scarcity is not a problem, then other approaches are necessary.

Scanlan and colleagues argue that food scarcity is, in fact, not the problem that international agencies and most people believe it to be:

The bigger problem with emphasizing food supply as the problem, however, is that scarcity is largely a myth. On a per capita basis, food is more plentiful today than any other time in human history.…[E]ven in times of localized production shortfalls or regional famines there has long been a global food surplus. (p. 35)

If the problem is not a lack of food, then what is the problem? Scanlan and colleagues argue that the real problem is a lack of access to food and a lack of equitable distribution of food: “Rather than food scarcity, then, we should focus our attention on the persistent inequalities that often accompany the growth in food supply” (p. 36).

What are these inequalities? Recognizing that hunger is especially concentrated in the poorest nations, the authors note that these nations lack the funds to import the abundant food that does exist. These nations’ poverty, then, is one inequality that leads to world hunger, but gender and ethnic inequalities are also responsible. For example, women around the world are more likely than men to suffer from hunger, and hunger is more common in nations with greater rates of gender inequality (as measured by gender differences in education and income, among other criteria). Hunger is also more common among ethnic minorities not only in poor nations but also in wealthier nations. In findings from their own research, these sociologists add, hunger lessens when nations democratize, when political rights are protected, and when gender and ethnic inequality is reduced.

If inequality underlies world hunger, they add, then efforts to reduce world hunger will succeed only to the extent that they recognize the importance of inequality in this regard: “To get at inequality, policy must give attention to democratic governance and human rights, fixing the politics of food aid, and tending to the challenges posed by the global economy” (p. 38). For this to happen, they say, food must be upheld as a “fundamental human right.” More generally, world hunger cannot be effectively reduced unless and until ethnic and gender inequality is reduced. Scanlan and colleagues conclude,

The challenge, in short, is to create a more equitable and just society in which food access is ensured for all. Food scarcity matters. However, it is rooted in social conditions and institutional dynamics that must be the focus of any policy innovations that might make a real difference. (p. 39)

In calling attention to the myth of food scarcity and the inequalities that contribute to world hunger, Scanlan and colleagues point to better strategies for addressing this significant international problem. Once again, sociology is making a difference.

Concern over population growth also decreased because of criticism by people of color that ZPG was directed largely at their ranks and smacked of racism. The call for population control, they said, was a disguised call for controlling the growth of their own populations and thus reducing their influence (Kuumba, 1993).Kuumba, M. B. (1993). Perpetuating neo-colonialism through population control: South Africa and the United States. Africa Today, 40(3), 79–85.

Still another reason for the reduced concern over population growth is that birth rates in many industrial nations have slowed considerably. Some nations are even experiencing population declines, while several more are projected to have population declines by 2050 (Goldstein, Sobotka, & Jasilioniene, 2009).Goldstein, J. R., Sobotka, T., & Jasilioniene, A. (2009). The end of “lowest-low” fertility? Population & Development Review, 35(4), 663–699. doi:10.1111/j.1728–4457.2009.00304.x For a country to maintain its population, the average woman needs to have 2.1 children, the replacement level for population stability. But several industrial nations, not including the United States, are far below this level. Increased birth control is one reason for their lower fertility rates, but so are the decisions by women to stay in school longer and then to go to work right after their schooling ends and not having their first child until somewhat later.

Figure 14.4

Spain is one of several European nations that have been experiencing a population decline because of lower birth rates. Like some other nations, Spain has adopted pronatalist policies to encourage people to have more children; it provides 2,500 euros, about $3,400, for each child.

Source: Photo courtesy of Sergi Larripa, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BCN01.JPG.

Ironically, these nations’ population declines have begun to concern demographers and policy makers (Shorto, 2008).Shorto, R. (2008, June 2). No babies? The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/29/magazine/29Birth-t.html?scp=1&sq=&st=nyt Because people in many industrial nations are living longer while the birth rate drops, these nations are increasingly having a greater proportion of older people and a smaller proportion of younger people. In several European nations, there are more people 61 or older than 19 or younger. As this trend continues, it will become increasingly difficult to take care of the health and income needs of so many older persons, and there may be too few younger people to fill the many jobs and provide the many services that an industrial society demands. The smaller labor force may also mean that governments will have fewer income tax dollars to provide these services.

To deal with these problems, several governments have initiated pronatalist policies aimed at encouraging women to have more children. In particular, they provide generous child-care subsidies, tax incentives, and flexible work schedules designed to make it easier to bear and raise children, and some even provide couples outright cash payments when they have an additional child. Russia in some cases provides the equivalent of about $9,000 for each child beyond the first, while Spain provides 2,500 euros (equivalent to about $3,400) for each child (Haub, 2009).Haub, C. (2009). Birth rates rising in some low birth-rate countries. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau. Retrieved from http://www.prb.org/Articles/2009/fallingbirthrates.aspx

Demography and Demographic Concepts

As all of these issues indicate, changes in the size and composition of population have important implications for other social changes. The study of population is so significant that it occupies a special subfield within sociology called demographyThe study of population growth and changes in population composition.. To be more precise, demography is the study of changes in the size and composition of population. It encompasses several concepts: fertility and birth rates, mortality and death rates, and migration (Weeks, 2008).Weeks, J. R. (2008). Population: An introduction to concepts and issues (10th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. Let’s look at each of these briefly.

Fertility and Birth Rates

FertilityThe number of live births. refers to the number of live births. Demographers use several measures of fertility. One measure is the crude birth rateThe number of live births for every 1,000 people in a population in a given year., or the number of live births for every 1,000 people in a population in a given year. To determine the crude birth rate, the number of live births in a year is divided by the population size, and this result is then multiplied by 1,000. For example, in 2008 the United States had a population of about 304 million and 4,251,095 births. Dividing the latter figure by the former figure gives us 0.0140 rounded off. We then multiply this quotient by 1,000 to yield a crude birth rate of 14.0 births per 1,000 population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab We call this a “crude” birth rate because the denominator, population size, consists of the total population, not just the number of women or even the number of women of childbearing age (commonly considered 15–44).

A second measure is the general fertility rateThe number of live births per 1,000 women aged 15–44. (also just called the fertility rate or birth rate), or the number of live births per 1,000 women aged 15–44 (i.e., of childbearing age). This is calculated in a manner similar to that for the crude fertility rate, but in this case the number of births is divided by the number of women aged 15–44 before multiplying by 1,000. The U.S. general fertility rate for 2007 was about 69.5 (i.e., 69.5 births per 1,000 women aged 15–44) (Hamilton, Martin, & Ventura, 2009).Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., & Ventura, S. J. (2009). Births: Preliminary data for 2007. National Vital Statistics Reports, 57(12), 1–12.

A third measure is the total fertility rateThe number of children an average woman is expected to have in her lifetime, sometimes expressed as the number of children an average 1,000 women are expected to have in their lifetimes., or the number of children an average woman is expected to have in her lifetime. This measure often appears in the news media and is more easily understood by the public than either of the first two measures. In 2007, the U.S. total fertility rate was 2.1. Sometimes the total fertility rate is expressed as the average number of births that an average group of 1,000 women would be expected to have. In this case, the average number of children that one woman is expected to have is simply multiplied by 1,000. Using this latter calculation, the U.S. total fertility rate in 2007 was 2,100 (i.e., an average group of 1,000 women would be expected to have, in their lifetimes, 2,100 children) (Hamilton et al., 2009).Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., & Ventura, S. J. (2009). Births: Preliminary data for 2007. National Vital Statistics Reports, 57(12), 1–12.

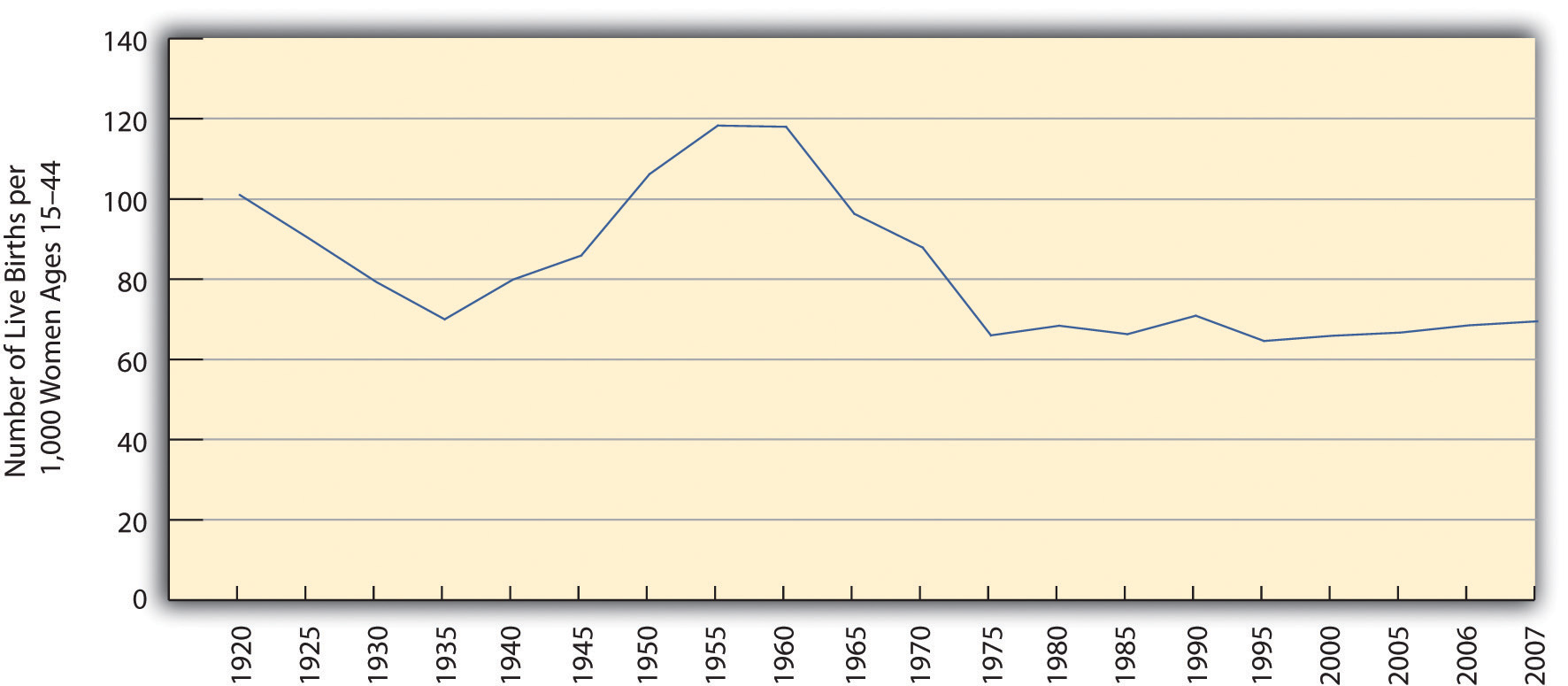

As Figure 14.5 "U.S. General Fertility Rate, 1920–2007" indicates, the U.S. general fertility rate has changed a lot since 1920, dropping from 101 (per 1,000 women aged 15–44) in 1920 to 70 in 1935, during the Great Depression, before rising afterward until 1955. (Note the very sharp increase from 1945 to 1955, as the post–World War II baby boom began.) The fertility rate then fell steadily after 1960 until the 1970s but has remained rather steady since then, fluctuating only slightly between 65 and 70 per 1,000 women aged 15–44.

Figure 14.5 U.S. General Fertility Rate, 1920–2007

Sources: Data from Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Sutton, P. D., Ventura, S. J., Menacker, F., Kirmeyer, S., & Mathews, T. J. (2009). Births: Final data for 2006. National Vital Statistics Reports, 57(7), 1–102; U.S. Census Bureau. (1951). Statistical abstract of the United States: 1951. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; U.S. Census Bureau. (2011). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2011. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab.

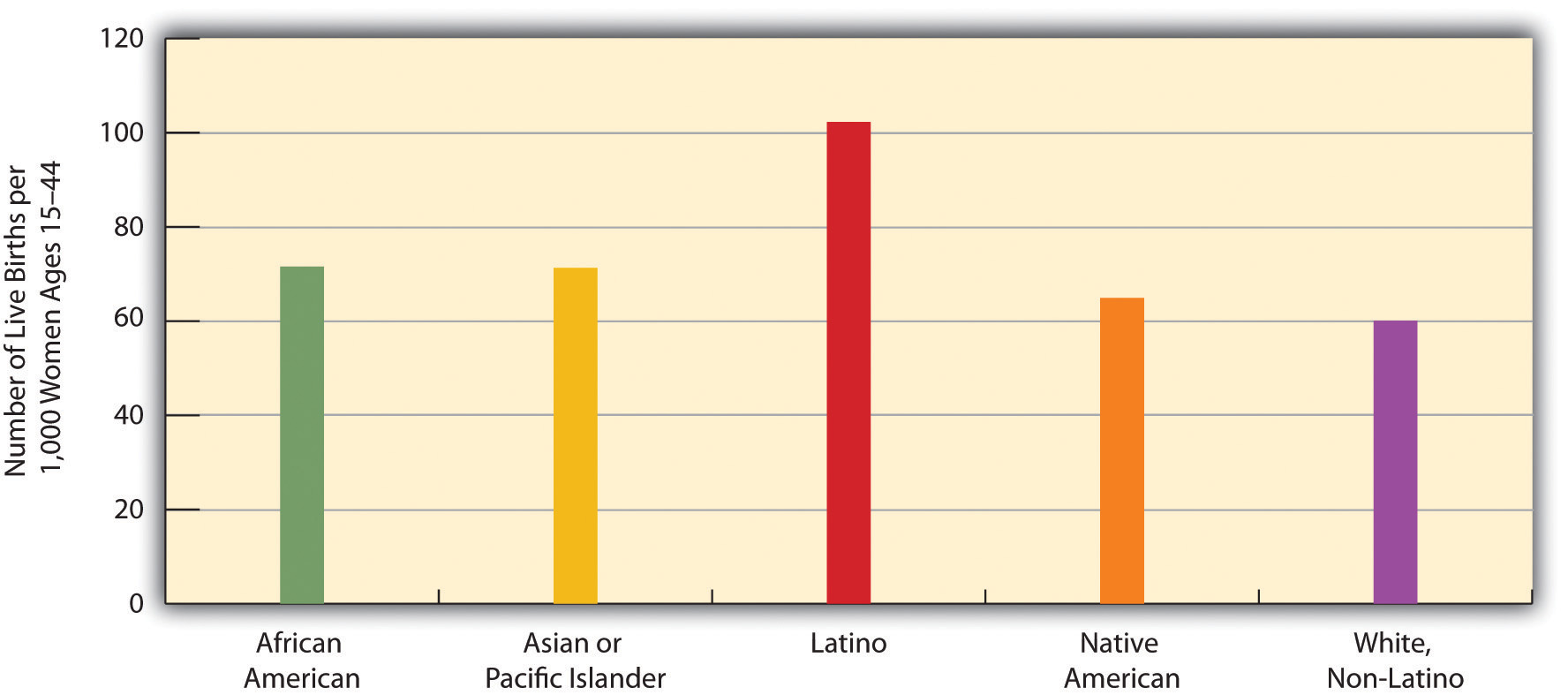

The fertility rate varies by race and ethnicity. As Figure 14.6 "Race, Ethnicity, and U.S. Fertility Rates, 2007" shows, it is lowest for non-Latina white women and the highest for Latina women. Along with immigration, the high fertility rate of Latina women has fueled the large growth of the Latino population. Latinos now account for about 16% of the U.S. population, and their proportion is expected to reach more than 30% by 2050 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab

Figure 14.6 Race, Ethnicity, and U.S. Fertility Rates, 2007

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau. (2011). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2011. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab.

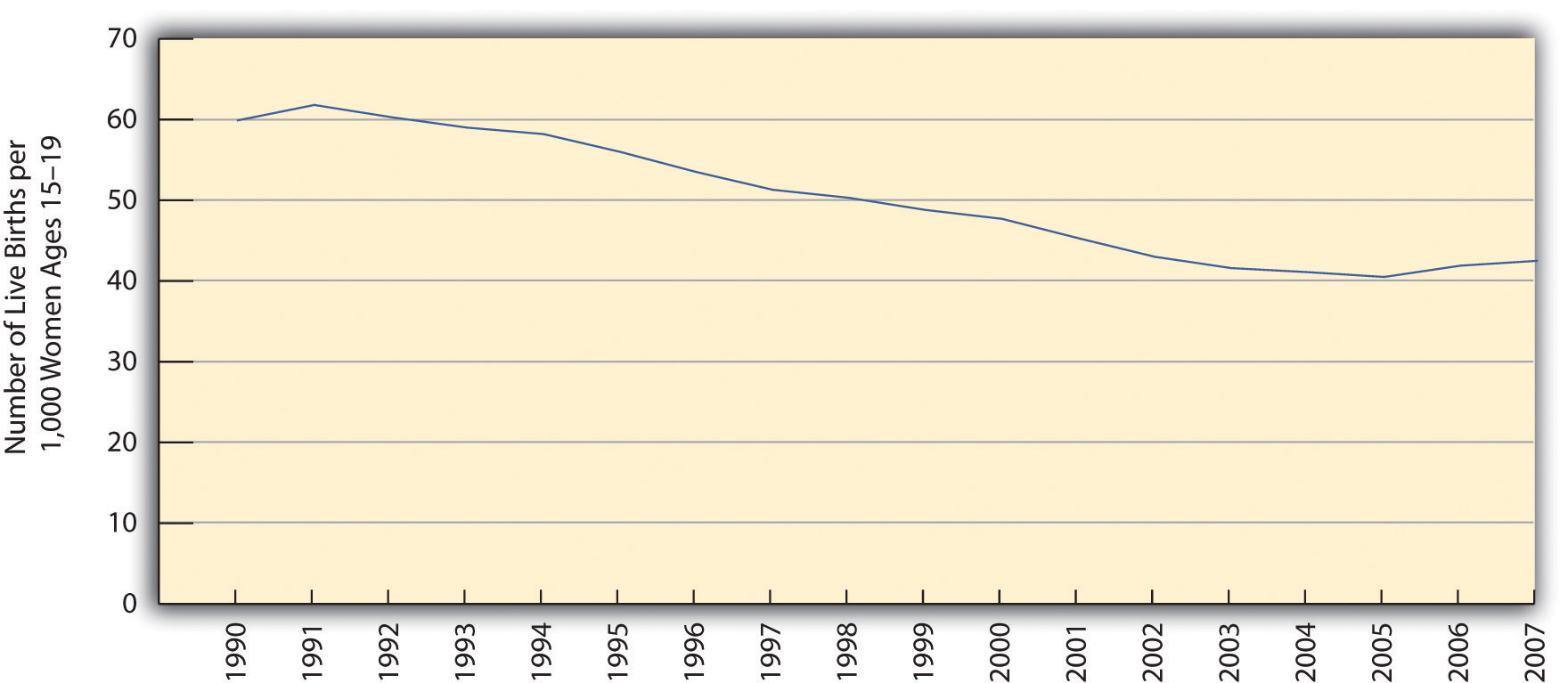

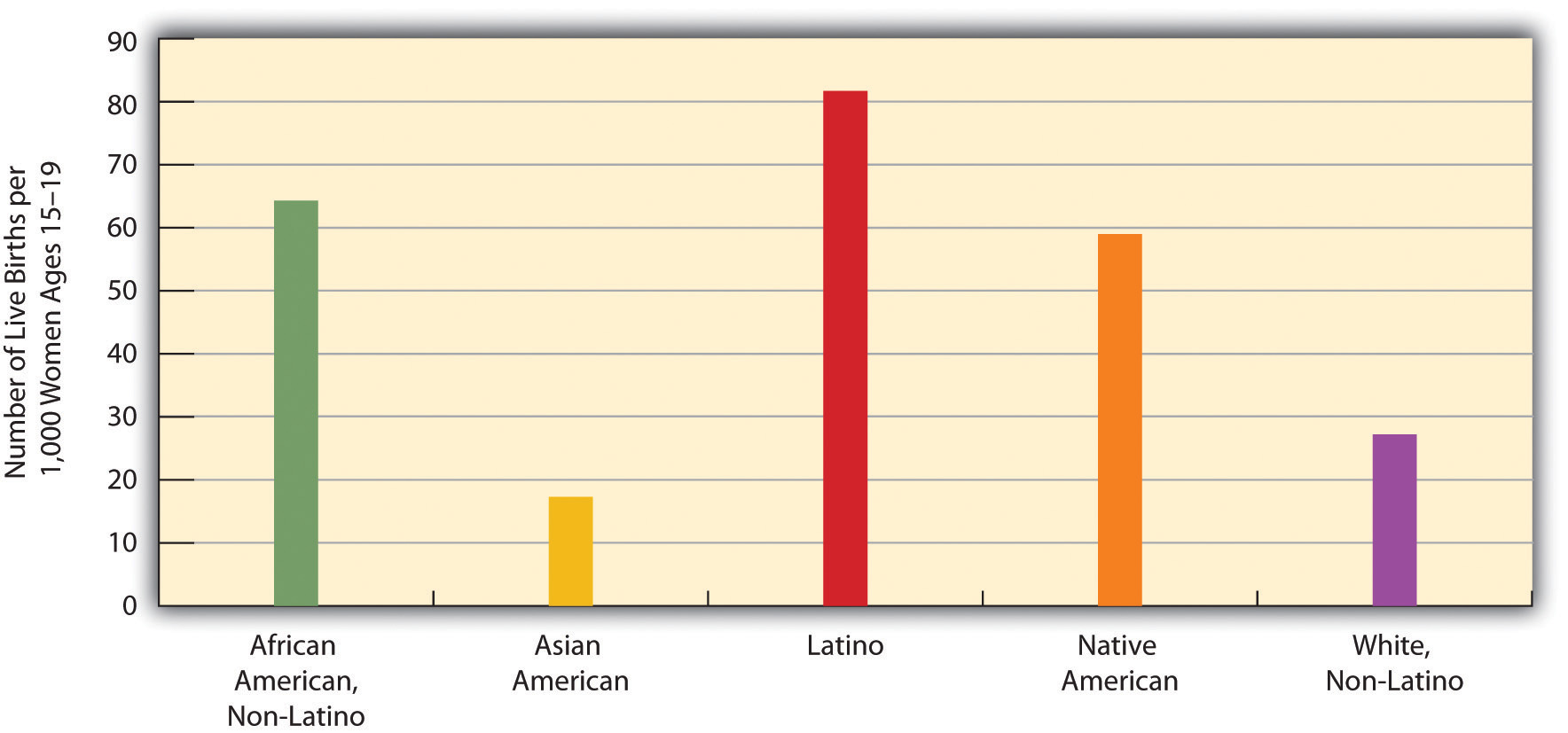

The fertility rate of teenagers is a special concern because of their age. Although it is still a rate that most people wish were lower, it dropped steadily through the 1990s, before leveling off after 2002 and rising slightly by 2007 (see Figure 14.7 "U.S. Teenage Fertility Rate, 1990–2007"). Although most experts attribute this drop to public education campaigns and increased contraception, the United States still has the highest rate of teenage pregnancy and fertility of any industrial nation (Eckholm, 2009).Eckholm, E. (2009, March 18). ’07 U.S. births break baby boom record. The New York Times, p. A14. Teenage fertility again varies by race and ethnicity, with Latina teenagers having the highest fertility rates and Asian American teenagers the lowest (see Figure 14.8 "Race, Ethnicity, and U.S. Teenage Fertility Rates, 2007").

Figure 14.7 U.S. Teenage Fertility Rate, 1990–2007

Sources: Data from Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Sutton, P. D., Ventura, S. J., Menacker, F., Kirmeyer, S., & Mathews, T. J. (2009). Births: Final data for 2006. National Vital Statistics Reports, 57(7), 1–102; U.S. Census Bureau. (2011). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2011. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab.

Figure 14.8 Race, Ethnicity, and U.S. Teenage Fertility Rates, 2007

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab.

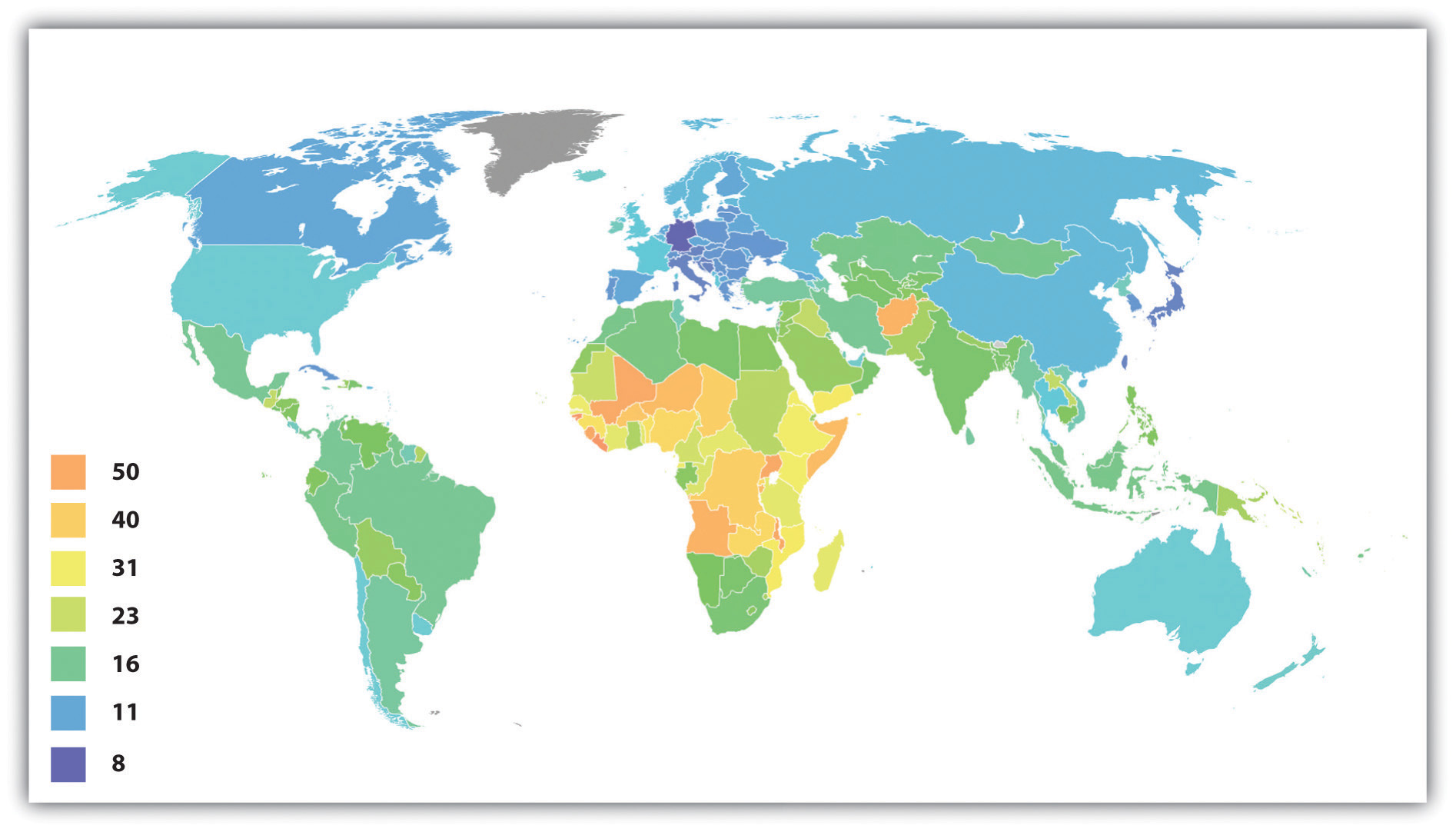

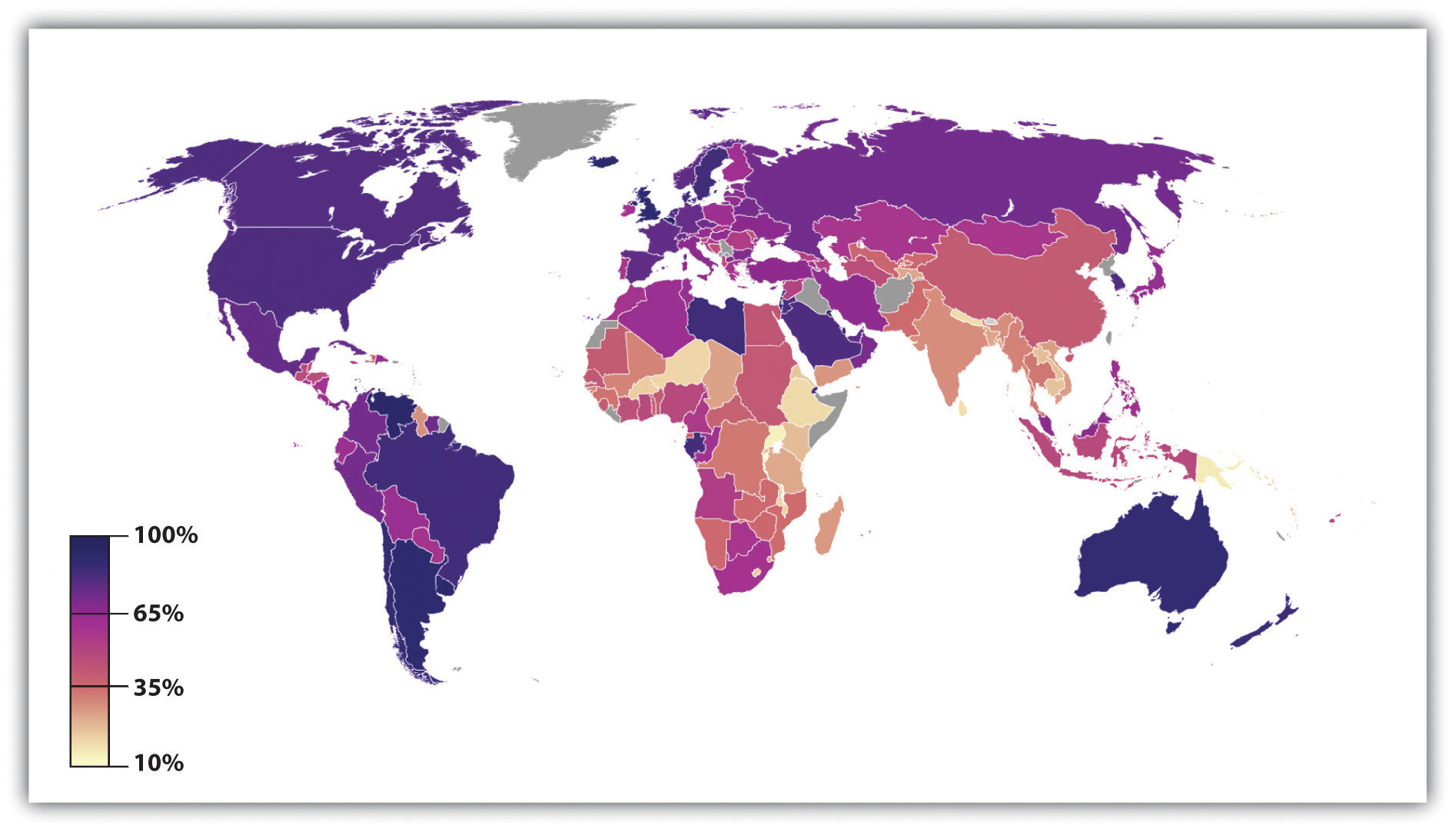

Fertility rates also differ around the world and are especially high in poor nations (see Figure 14.9 "Crude Birth Rates Around the World, 2008 (Number of Births per 1,000 Population)"). Demographers identify several reasons for these high rates (Weeks, 2008).Weeks, J. R. (2008). Population: An introduction to concepts and issues (10th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Figure 14.9 Crude Birth Rates Around the World, 2008 (Number of Births per 1,000 Population)

Source: Adapted from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Birth_rate_figures_for_countries.PNG.

First, poor nations are usually agricultural ones. In agricultural societies, children are an important economic resource, as a family will be more productive if it has more children. This means that families will ordinarily try to have as many children as possible. Second, infant and child mortality rates are high in these nations. Because parents realize that one or more of their children may die before adulthood, they have more children to “make up” for the anticipated deaths. A third reason is that many parents in low-income nations prefer sons to daughters, and, if a daughter is born, they “try again” for a son. Fourth, traditional gender roles are often very strong in poor nations, and these roles include the belief that women should be wives and mothers above all. With this ideology in place, it is not surprising that women will have several children. Finally, contraception is uncommon in poor nations. Without contraception, many more pregnancies and births obviously occur. For all of these reasons, then, fertility is much higher in poor nations than in rich nations.

Mortality and Death Rates

MortalityThe number of deaths. is the flip side of fertility and refers to the number of deaths. Demographers measure it with the crude death rateThe number of deaths for every 1,000 people in a population in a given year., the number of deaths for every 1,000 people in a population in a given year. To determine the crude death rate, the number of deaths is divided by the population size, and this result is then multiplied by 1,000. In 2006 the United States had slightly more than 2.4 million deaths for a crude death rate of 8.1 deaths for every 1,000 persons. We call this a “crude” death rate because the denominator, population size, consists of the total population and does not take its age distribution into account. All things equal, a society with a higher proportion of older people should have a higher crude death rate. Demographers often calculate age-adjusted death rates that adjust for a population’s age distribution.

Migration

Another demographic concept is migrationThe movement of people into or out of specific regions., the movement of people into and out of specific regions. Since the dawn of human history, people have migrated in search of a better life, and many have been forced to migrate by ethnic conflict or the slave trade.

Several classifications of migration exist. When people move into a region, we call it in-migration, or immigration; when they move out of a region, we call it out-migration, or emigration. The in-migration rate is the number of people moving into a region for every 1,000 people in the region, while the out-migration rate is the number of people moving from the region for every 1,000 people. The difference between the two is the net migration rate (in-migration minus out-migration).

Migration can also be either domestic or international in scope. Domestic migration happens within a country’s national borders, as when retired people from the northeastern United States move to Florida or the Southwest. International migration happens across national borders. When international immigration is heavy, as it has been into the United States and Western Europe in the last few decades, the effect on population growth and other aspects of national life can be significant. Domestic migration can also have a large impact. The great migration of African Americans from the South into northern cities during the first half of the 20th century changed many aspects of those cities’ lives (Berlin, 2010).Berlin, I. (2010). The making of African America: The four great migrations. New York, NY: Viking. Meanwhile, the movement during the past few decades of northerners into the South and Southwest also had quite an impact: the housing market initially exploded, for example, and traffic increased.

Population Growth

Now that you are familiar with some basic demographic concepts, we can discuss population growth in more detail. Three of the factors just discussed determine population growth: fertility (crude birth rate), mortality (crude death rate), and net migration. The natural growth rate is simply the difference between the crude birth rate and the crude death rate. The U.S. natural growth rate is about 0.6% (or 6 per 1,000 people) per year (Rosenberg, 2009).Rosenberg, M. (2009). Population growth rates. Retrieved from http://geography.about.com/od/populationgeography/a/populationgrow.htm When immigration is also taken into account, the total population growth rate has been almost 1.0% per year (Jacobsen & Mather, 2010).Jacobsen, L. A., & Mather, M. (2010). U.S. economic and social trends since 2000. Population Bulletin, 65(1), 1–20.

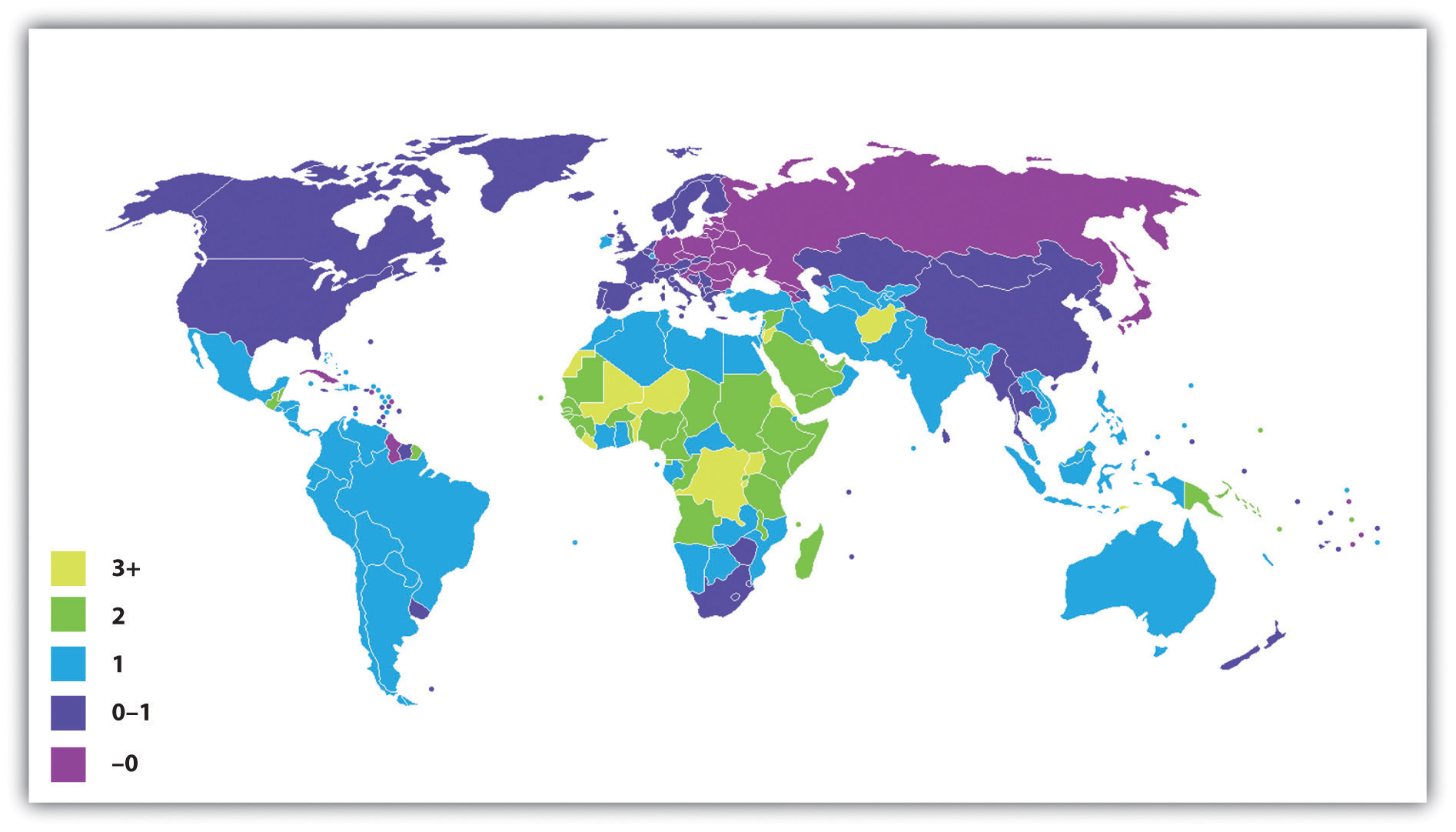

Figure 14.10 "International Annual Population Growth Rates (%), 2005–2010" depicts the annual population growth rate (including both natural growth and net migration) of all the nations in the world. Note that many African nations are growing by at least 3% per year or more, while most European nations are growing by much less than 1% or are even losing population, as discussed earlier. Overall, the world population is growing by about 80 million people annually.

Figure 14.10 International Annual Population Growth Rates (%), 2005–2010

Source: Adapted from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Population_growth_rate_world_2005-2010_UN.PNG.

To determine how long it takes for a nation to double its population size, divide the number 70 by its population growth rate. For example, if a nation has an annual growth rate of 3%, it takes about 23.3 years (70 ÷ 3) for that nation’s population size to double. As you can see from the map in Figure 14.10 "International Annual Population Growth Rates (%), 2005–2010", several nations will see their population size double in this time span if their annual growth continues at its present rate. For these nations, population growth will be a serious problem if food and other resources are not adequately distributed.

Demographers use their knowledge of fertility, mortality, and migration trends to make projections about population growth and decline several decades into the future. Coupled with our knowledge of past population sizes, these projections allow us to understand population trends over many generations. One clear pattern emerges from the study of population growth. When a society is small, population growth is slow because there are relatively few adults to procreate. But as the number of people grows over time, so does the number of adults. More and more procreation thus occurs every single generation, and population growth then soars in a virtual explosion.

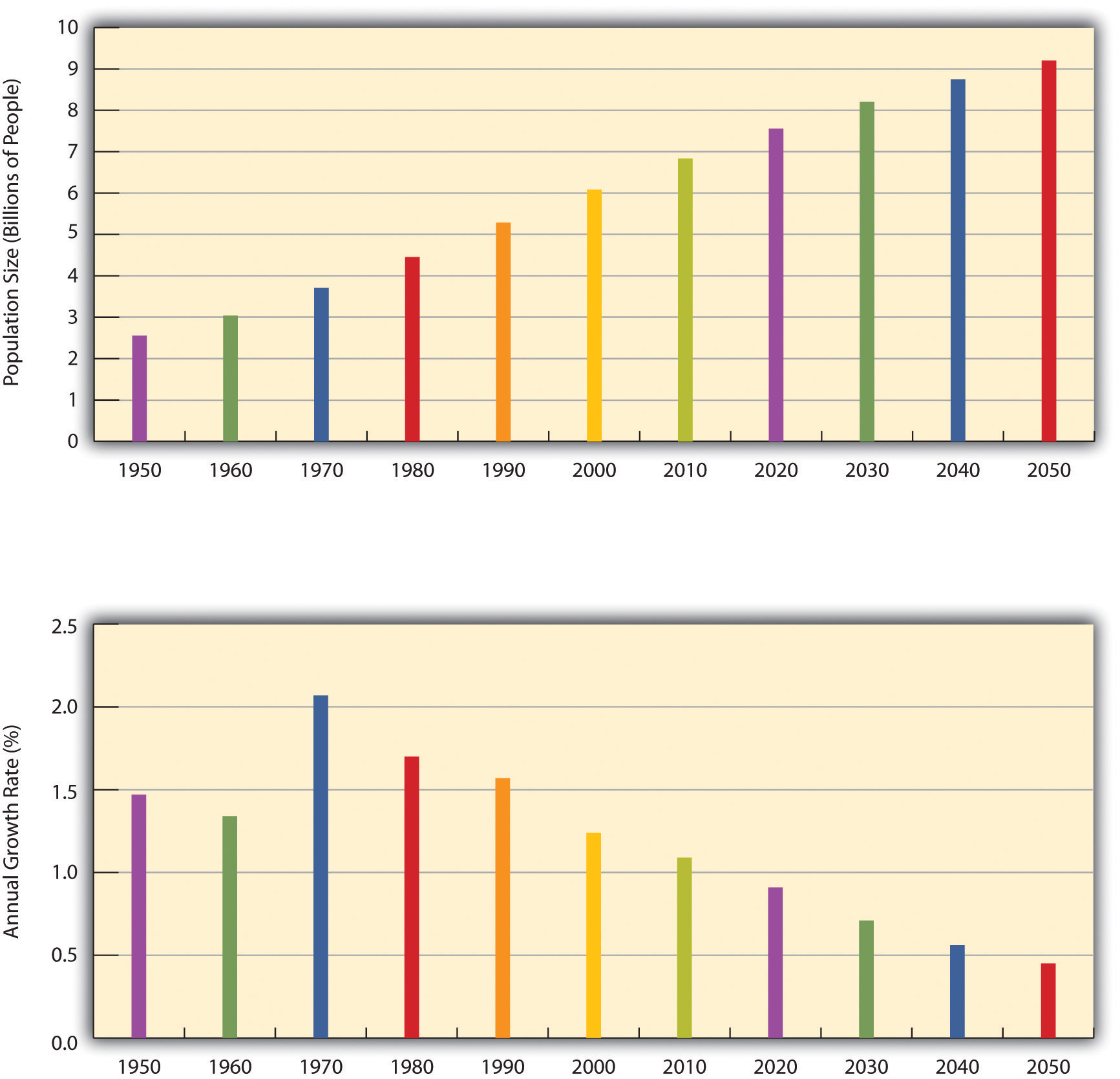

We saw evidence of this pattern when we looked at world population growth. When agricultural societies developed some 12,000 years ago, only about 8 million people occupied the planet. This number had reached about 300 million about 2,100 years ago, and by the 15th century it was still only about 500 million. It finally reached 1 billion by about 1850 and by 1950, only a century later, had doubled to 2 billion. Just 50 years later it tripled to more than 6.8 billion, and it is projected to reach more than 9 billion by 2050 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010)U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab (see Figure 14.11 "Total World Population, 1950–2050").

Figure 14.11 Total World Population, 1950–2050

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab.

Eventually, however, population growth begins to level off after exploding, as explained by demographic transition theory, discussed later. We see this in the bottom half of Figure 14.11 "Total World Population, 1950–2050", which shows the average annual growth rate for the world’s population. This rate has declined over the last few decades and is projected to further decline over the next four decades. This means that while the world’s population will continue to grow during the foreseeable future, it will grow by a smaller rate as time goes by. As Figure 14.10 "International Annual Population Growth Rates (%), 2005–2010" suggested, the growth that does occur will be concentrated in the poor nations in Africa and some other parts of the world. Still, even there the average number of children a woman has in her lifetime dropped from six a generation ago to about three today.

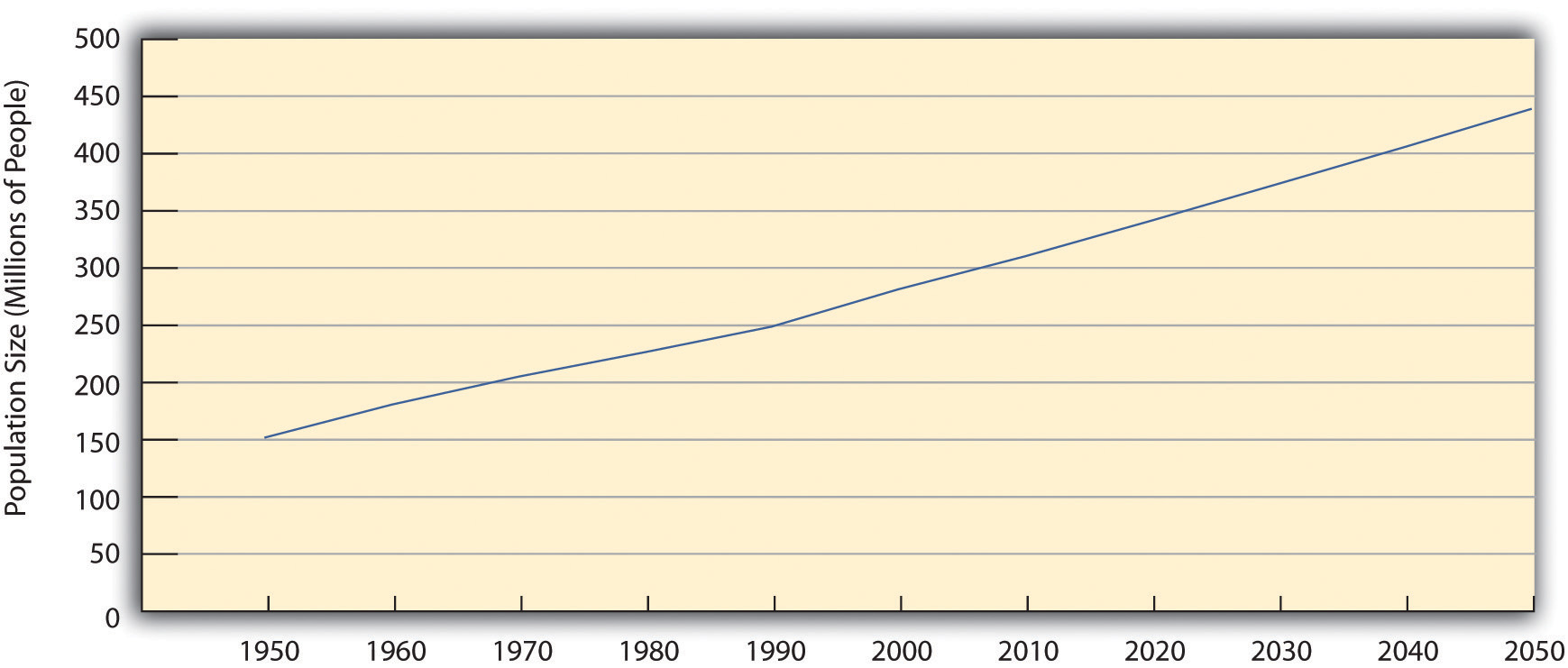

Past and projected sizes of the U.S. population appear in Figure 14.12 "Past and Projected Size of the U.S. Population, 1950–2050 (in Millions)". The U.S. population is expected to number about 440 million people by 2050.

Figure 14.12 Past and Projected Size of the U.S. Population, 1950–2050 (in Millions)

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab.

Views of Population Growth

Earlier we talked about the zero population growth movement and concern about overpopulation that received so much attention a generation ago. Social observers have actually worried about overpopulation since the 18th century.

Figure 14.13

Thomas Malthus, an English economist who lived about 200 years ago, wrote that population increases geometrically while food production increases only arithmetically. These understandings led him to predict mass starvation.

One of the first to warn about population growth was Thomas Malthus (1766–1834), an English economist, who said that population increases geometrically (2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024…). If you expand this list of numbers, you will see that they soon become overwhelmingly large in just a few more “generations.” Malthus (1798/1926)Malthus, T. R. (1926). First essay on population. London, England: Macmillan. (Original work published 1798) said that food production increases only arithmetically (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6…) and thus could not hope to keep up with the population increase, and he predicted that mass starvation would be the dire result.

Fortunately, Malthus was wrong to some degree. Although population levels have certainly soared, the projections in Figure 14.11 "Total World Population, 1950–2050" show that the rate of increase is slowing. Among other factors, the development of more effective contraception, especially the birth control pill, has limited population growth in the industrial world and, increasingly, in poorer nations. Food production has also increased by a much greater amount than Malthus predicted, although, as noted earlier, hunger remains a serious problem in poor nations because of inequalities in food distribution.

Demographic Transition Theory

Other factors also explain why population growth has not risen at the geometric rate that Malthus predicted and is even slowing. The view explaining the interaction of these factors is called demographic transition theoryA theory that links population growth to the level of technological development across three stages of social evolution. (Weeks, 2008),Weeks, J. R. (2008). Population: An introduction to concepts and issues (10th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. mentioned earlier. This theory links population growth to the level of technological development across three stages of social evolution. In the first stage, coinciding with preindustrial societies, the birth rate and death rate are both high. The birth rate is high because of the lack of contraception and the several other reasons cited earlier for high fertility rates, and the death rate is high because of disease, poor nutrition, lack of modern medicine, and other problems. These two high rates cancel each other out, and little population growth occurs.

In the second stage, coinciding with the development of industrial societies, the birth rate remains fairly high, owing to the lack of contraception and a continuing belief in the value of large families, but the death rate drops because of several factors, including increased food production, better sanitation, and improved medicine. Because the birth rate remains high but the death rate drops, population growth takes off dramatically.

In the third stage, the death rate remains low, but the birth rate finally drops as families begin to realize that large numbers of children in an industrial economy are more of a burden than an asset. Another reason for the drop is the availability of effective contraception. As a result, population growth slows, and, as we saw earlier, it has become quite low or even gone into a decline in several industrial nations.

Demographic transition theory gives us reason to be cautiously optimistic regarding the threat of overpopulation. As poor nations continue to modernize—much as industrial nations did 200 years ago—their population growth rates should start to decline. Still, population growth rates in poor nations continue to be high, and, as the “Sociology Making a Difference” box discussed, inequalities in food distribution allow rampant hunger to persist. Hundreds of thousands of women die in poor nations each year during pregnancy and childbirth. Reduced fertility would save their lives, in part because their bodies would be healthier if their pregnancies were spaced farther apart (Schultz, 2008).Schultz, T. P. (2008). Population policies, fertility, women’s human capital, and child quality. In T. P. Schultz & J. Strauss (Eds.), Handbook of development economics (Vol. 4, pp. 3249–3303). Amsterdam, Netherlands: North-Holland, Elsevier. Although world population growth is slowing, then, it is still growing too rapidly in much of the developing and least developed worlds. To reduce it further, more extensive family-planning programs are needed, as is economic development in general.

Key Takeaways

- Concern over population growth has declined for at least three reasons. First, there is increasing recognition that the world has an adequate supply of food. Second, people of color have charged that attempts to limit population growth were aimed at their own populations. Third, several European countries have actually experienced population decline.

- To understand changes in the size and composition of population, demographers use several concepts, including fertility and birth rates, mortality and death rates, and migration.

- Demographic transition theory links population growth to the level of technological development across three stages of social evolution. In preindustrial societies, there is little population growth; in industrial societies, population growth is high; and in later stages of industrial societies, population growth slows.

For Your Review

- Before you read this chapter, did you think that food scarcity was the major reason for world hunger today? Why do you think a belief in food scarcity is so common among Americans?

- The text states that the average woman must have 2.1 children for a society to avoid population decline. Some women wish to have no children, some desire one or two children, and some prefer to have at least three children. What do you think is the ideal number of children for a woman to have? Explain your answer.

14.3 Urbanization

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the views and methodology of the human ecology school.

- Describe the major types of urban residents.

- List four major issues and/or problems affecting U.S. cities today.

An important aspect of social change and population growth over the centuries has been urbanizationThe rise and growth of cities., or the rise and growth of cities. Urbanization has had important consequences for many aspects of social, political, and economic life (Macionis & Parrillo, 2010).Macionis, J. J., & Parrillo, V. N. (2010). Cities and urban life (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

The earliest cities developed in ancient times after the rise of horticultural and pastoral societies made it possible for people to stay in one place instead of having to move around to find food. Because ancient cities had no sanitation facilities, people typically left their garbage and human waste in the city streets or just outside the city wall (which most cities had for protection from possible enemies); this poor sanitation led to rampant disease and high death rates. Some cities eventually developed better sanitation procedures, including, in Rome, a sewer system (Smith, 2003).Smith, M. L. (Ed.). (2003). The social construction of ancient cities. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Cities became more numerous and much larger during industrialization, as people moved to be near factories and other sites of industrial production. First in Europe and then in the United States, people crowded together as never before into living conditions that were often decrepit. Lack of sanitation continued to cause rampant disease, and death rates from cholera, typhoid, and other illnesses were high. In addition, crime rates soared, and mob violence became quite common (Feldberg, 1998).Feldberg, M. (1998). Urbanization as a cause of violence: Philadelphia as a test case. In A. F. Davis & M. H. Haller (Eds.), The peoples of Philadelphia: A history of ethnic groups and lower-class life, 1790–1940 (pp. 53–69). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Views of the City

Are cities good or bad? We asked a similar question—is modernization good or bad?—earlier in this chapter, and the answer here is similar as well: cities are both good and bad. They are sites of innovation, high culture, population diversity, and excitement, but they are also sites of high crime, impersonality, and other problems.

Figure 14.14

During the early 20th century, social scientists at the University of Chicago began to study urban life in general and life in Chicago in particular. Although some of these scholars were very dismayed by the negative aspects of city life, other scholars emphasized several positive aspects of city life.

In the early 20th century, a group of social scientists at the University of Chicago established a research agenda on cities that is still influential today (Bulmer, 1984).Bulmer, M. (1984). The Chicago school of sociology: Institutionalization, diversity, and the rise of sociological research. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Most notably, they began to study the effects of urbanization on various aspects of city residents’ lives in what came to be called the human ecology schoolThe study by early University of Chicago sociologists of the effects of urbanization on various aspects of city residents’ lives. (Park, Burgess, & McKenzie, 1925).Park, R. E., Burgess, E. W., & McKenzie, R. (1925). The city. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. One of their innovations was to divide Chicago into geographical regions, or zones, and to analyze crime rates and other behavioral differences among the zones. They found that crime rates were higher in the inner zone, or central part of the city, where housing was crowded and poverty was common, and were lower in the outer zones, or the outer edges of the city, where houses were spread farther apart and poverty was much lower. Because they found these crime rate differences over time even as the ethnic backgrounds of people in these zones changed, they assumed that the social and physical features of the neighborhoods were affecting their crime rates (Shaw & McKay, 1942).Shaw, C. R., & McKay, H. D. (1942). Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Their work is still useful today, as it helps us realize that the social environment, broadly defined, can affect our attitudes and behavior. This theme, of course, lies at the heart of the sociological perspective.

Urbanism and Tolerance

One of the most notable Chicago sociologists was Louis Wirth (1897–1952), who, in a well-known essay entitled “Urbanism as a Way of Life” (Wirth, 1938),Wirth, L. (1938). Urbanism as a way of life. American Journal of Sociology, 44, 3–24. discussed several differences between urban and rural life. In one such difference, he said that urban residents are more tolerant than rural residents of nontraditional attitudes, behaviors, and lifestyles, in part because they are much more exposed than rural residents to these nontraditional ways. Supporting Wirth’s hypothesis, contemporary research finds that urban residents indeed hold more tolerant views on several kinds of issues (Moore & Ovadia, 2006).Moore, L. M., & Ovadia, S. (2006). Accounting for spatial variation in tolerance: The effects of education and religion. Social Forces, 84(4), 2205–2222.

Life in U.S. Cities

Life in U.S. cities today reflects the dual view just outlined. On the one hand, many U.S. cities are vibrant places, filled with museums and other cultural attractions, nightclubs, theaters, and restaurants and populated by people from many walks of life and from varied racial and ethnic and national backgrounds. Many college graduates flock to cities, not only for their employment opportunities but also for their many activities and the sheer excitement of living in a metropolis. On the other hand, many U.S. cities are also filled with abject poverty, filth and dilapidated housing, high crime rates, traffic gridlock, and dirty air. Many Americans would live nowhere but a city, and many would live anywhere but a city. Cities arouse strong opinions pro and con, and for good reason, because there are many things both to like and to dislike about cities.

Types of Urban Residents

The quality of city life depends on many factors, but one of the most important factors is a person’s social background: social class, race and ethnicity, gender, age, and sexual orientation. As earlier chapters documented, these dimensions of our social backgrounds often yield many kinds of social inequalities, and the quality of life that city residents enjoy depends heavily on these dimensions. For example, residents who are white and wealthy have the money and access to enjoy the best that cities have to offer, while those who are poor and of color typically experience the worst aspects of city life. Because of fear of rape and sexual assault, women often feel more constrained than men from traveling freely throughout a city and being out late at night; older people also often feel more constrained because of physical limitations and fear of muggings; and gays and lesbians are still subject to physical assaults stemming from homophobia. The type of resident we are, then, in terms of our sociodemographic profile affects what we experience in the city and whether that experience is positive or negative.

This brief profile of city residents obscures other kinds of differences among residents regarding their lifestyles and experiences. A classic typology of urban dwellers by sociologist Herbert Gans (1962)Gans, H. J. (1962). The urban villagers: Group and class in the life of Italian-Americans. New York, NY: Free Press. is still useful today in helping to understand the variety of lives found in cities. Gans identified five types of city residents.

The first type is cosmopolites. These are people who live in a city because of its cultural attractions, restaurants, and other features of the best that a city has to offer. Cosmopolites include students, writers, musicians, and intellectuals. Unmarried and childless individuals and couples are the second type; they live in a city to be near their jobs and to enjoy the various kinds of entertainment found in most cities. If and when they marry or have children, respectively, many migrate to the suburbs to raise their families. The third type is ethnic villagers, who are recent immigrants and members of various ethnic groups who live among each other in certain neighborhoods. These neighborhoods tend to have strong social bonds and more generally a strong sense of community. Gans wrote that all of these three types generally find the city inviting rather than alienating and have positive experiences far more often than negative ones.

In contrast, two final types of residents find the city alienating and experience a low quality of life. The first of these two types, and the fourth overall, is the deprived. These are people with low levels of formal education who live in poverty or near-poverty and are unemployed, are underemployed, or work at low wages. They live in neighborhoods filled with trash, broken windows, and other signs of disorder. They commit high rates of crime and also have high rates of victimization by crime. The final type is the trapped. These are residents who, as their name implies, might wish to leave their neighborhoods but are unable to do so for several reasons: they may be alcoholics or drug addicts, they may be elderly and disabled, or they may be jobless and cannot afford to move to a better area.

Problems of City Life

By definition, cities consist of very large numbers of people living in a relatively small amount of space. Some of these people have a good deal of money, but many people, and in some cities most people, have very little money. Cities must provide many kinds of services for all their residents, and certain additional services for their poorer residents. These basic facts of city life make for common sets of problems affecting cities throughout the nation, albeit to varying degrees, with some cities less able than others to address these problems.

One evident problem is fiscal: cities typically have serious difficulties in paying for basic services such as policing, public education, trash removal, street maintenance, and, in cold climates, snow removal, and in providing certain services for their residents who are poor or disabled or who have other conditions. The fiscal difficulties that cities routinely face became even more serious with the onset of the nation’s deep recession in 2009, as the term fiscal crisis became a more accurate description of the harsh financial realities that cities were now facing (McNichol, 2009).McNichol, D. A. (2009, May 1). Revenue loss putting cities in fiscal vise. The New York Times, p. NJ1.

Figure 14.15

Cities experience many kinds of problems, and crowding is one of them. People who live amid crowding are more likely to experience stress and depression and to engage in aggressive behavior or be victimized by it.

© Thinkstock

Another problem is crowding. Cities are crowded in at least two ways. The first involves residential crowding: large numbers of people living in a small amount of space. City streets are filled with apartment buildings, condominiums, row houses, and other types of housing, and many people live on any one city block. The second type of crowding is household crowding: dwelling units in cities are typically small because of lack of space, and much smaller than houses in suburbs or rural areas. This forces many people to live in close quarters within a particular dwelling unit. Either type of crowding is associated with higher levels of stress, depression, and aggression (Regoeczi, 2008).Regoeczi, W. C. (2008). Crowding in context: An examination of the differential responses of men and women to high-density living environments. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 49, 254–268.

A third problem involves housing. Here there are two related issues. Much urban housing is substandard and characterized by such problems as broken windows, malfunctioning heating systems, peeling paint, and insect infestation. At the same time, adequate housing is not affordable for many city residents, as housing prices in cities can be very high, and the residents’ incomes are typically very low. Cities thus have a great need for adequate, affordable housing.

A fourth problem is traffic. Gridlock occurs in urban areas, not rural ones, because of the sheer volume of traffic and the sheer number of intersections controlled by traffic lights or stop signs. Some cities have better public transportation than others, but traffic and commuting are problems that urban residents experience every day (see the “Learning From Other Societies” box).

Learning From Other Societies

Trains, Not Planes (or Cars): The Promise of High-Speed Rail

One of the costs of urbanization and modern life is traffic. Our streets and highways are clogged with motor vehicles, and two major consequences of so much traffic are air pollution and tens of thousands of deaths and injuries from vehicular accidents. One way that many other nations, including China, Germany, Japan, and Spain, have tried to lessen highway traffic in recent decades is through the construction of high-speed rail lines. According to one news report, the U.S. rail system “remains a caboose” compared to the high-speed system found in much of the rest of the world (Knowlton, 2009, p. A16).Knowlton, B. (2009, April 16). Obama seeks high-speed rail system across U.S. The New York Times, p. A16. Japan has one line that averages 180 mph, while Europe’s high-speed trains average 130 mph, with some exceeding 200 mph. These speeds are far faster than the 75 mph typical of Amtrak’s speediest Acela line in the northeastern United States, which must usually go much more slowly than its top speed of 150 mph because of inferior tracking and interference by other trains. Although the first so-called bullet train appeared in Japan about 40 years ago, the United States does not yet have even one such train.

The introduction of high-speed rail in other nations was obviously meant to reduce highway traffic and, in turn, air pollution and vehicular injuries and deaths. Another goal was to reduce air traffic between cities, as high-speed trains emit only one-fourth the carbon dioxide per passengers as planes do while transporting eight times as many passengers in a given distance (Burnett, 2009).Burnett, V. (2009, May 29). Europe’s travels with high-speed rail hold lessons for U.S. planners; The Spanish experience has been transformative but far from inexpensive. International Herald Tribune, p. 16. A final goal was to aid the national economies of the nations that introduced high-speed rail. The evidence indicates that these goals have been accomplished.

For example, Spain built its first high-speed line, between Madrid and Seville, in 1992 and now has rail reaching about 1,200 miles between its north and south coasts. The rail network has increased travel for work and leisure and thus helped Spain’s economy. The high-speed trains are also being used instead of planes by the vast majority of people who travel between Madrid and either Barcelona or Seville.

China, the world’s most populous nation but far from the richest, has recently opened, or plans to open during the next few years, several dozen high-speed rail lines. Its fastest train averages more than 200 mph and travels 664 miles between two cities, Guangzhou and Wuhan, in just over 3 hours. The Acela takes longer to travel between Boston and New York, a distance of only 215 miles. A news report summarized the economic benefits for China:

Indeed, the web of superfast trains promises to make China even more economically competitive, connecting this vast country—roughly the same size as the United States—as never before, much as the building of the Interstate highway system increased productivity and reduced costs in America a half-century ago. (Bradsher, 2010, p. B1)Bradsher, K. (2010, February 12). China sees growth engine in a web of fast trains. The New York Times, p. B1.

In April 2009 President Barack Obama announced that $8 billion in federal stimulus funding would be made available for the construction of high-speed rail lines in certain parts of the United States to connect cities between 100 and 600 miles apart. The president said,

Imagine whisking through towns at speeds over 100 miles an hour, walking only a few steps to public transportation, and ending up just blocks from your destination. It is happening right now; it’s been happening for decades. The problem is, it’s been happening elsewhere, not here. (Knowlton, 2009)Knowlton, B. (2009, April 16). Obama seeks high-speed rail system across U.S. The New York Times, p. A16.

As large as it is, the $8 billion figure announced by Obama pales in comparison with an estimated $140 billion that Spain plans to further spend on high-speed rail during the next decade, and a system of high-speed rail in the United States will cost more than even this expenditure. Despite the huge expense of high-speed rail, the positive experience of other nations that are using it suggests that the United States will benefit in many ways from following their example. If it does not do so, said one scholar, “the American preference for clogged-up highways and airports will make the country look so old, so 20th-century-ish. So behind the times” (Kennedy, 2010).Kennedy, P. (2010, January 4). A trainspotter’s guide to the future of the world. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/05/opinion/05iht-edkennedy.html?scp=1&sq=A%20trainspotter’s%20guide%20to%20the%20future%20of%20the%20world&st=cse

A related problem is pollution. Traffic creates pollution from motor vehicles’ exhaust systems, and some cities have factories and other enterprises that also pollute. As a result, air quality in cities is substandard, and the poor quality of air in cities has been linked to respiratory and heart disease and higher mortality rates (Stylianou & Nicolich, 2009).Stylianou, M., & Nicolich, M. J. (2009). Cumulative effects and threshold levels in air pollution mortality: Data analysis of nine large US cities using the NMMAPS dataset. Environmental Pollution, 157, 2216–2223.

Yet another issue for cities is the state of their public education. Many city schools are housed in old buildings that, like much city housing, are falling apart. City schools are notoriously underfunded and lack current textbooks, adequate science equipment, and other instructional materials (see Chapter 12 "Education and Religion").