This is “Sociology and the Sociological Perspective”, chapter 1 from the book Sociology: Brief Edition (v. 1.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 1 Sociology and the Sociological Perspective

Americans live in a free country. Unlike people living in many other nations in the world, Americans generally have the right to think and do what we want—that is, as long as we do not hurt anyone else. We can choose to go to college or not to go; we can be conservative or be liberal; we can believe in a higher deity or not hold this belief; and we can decide to have a romantic relationship with whoever will have us or not to have such a relationship. We make up our own minds on such issues as abortion, affirmative action, the death penalty, gun control, health care, and taxes. We are individuals, and no one has the right to tell us what to do (as long as our actions are legal) or how to think.

1.1 The Sociological Perspective

Learning Objectives

- Define the sociological perspective.

- Provide examples of how Americans may not be as “free” as they think.

- Explain what is meant by considering individuals as “social beings.”

Most Americans probably agree that we enjoy a great amount of freedom. And yet perhaps we have less freedom than we think. Although we have the right to choose how to believe and act, many of our choices are affected by our society, culture, and social institutions in ways we do not even realize. Perhaps we are not as distinctively individualistic as we might like to think.

The following mental exercise should serve to illustrate this point. Your author has never met the readers of this book, and yet he already knows much about them and can even predict their futures. For example, about 85% of this book’s (heterosexual) readers will one day get married. This prediction will not always come true, but for every 100 readers, it will be correct about 85 times and wrong about 15 times. Because the author knows nothing about the readers other than that they live in the United States (and this might not be true for every reader of this Flat World Knowledge book), the accuracy of this prediction is remarkable.

The author can also predict the kind of person any one heterosexual reader will marry. If the reader is a woman, she will marry a man of her race who is somewhat older and taller and who is from her social class. If the reader is a man, he will marry a woman of his race who is somewhat younger and shorter and who is from his social class. A reader will even marry someone who is similar in appearance. A reader who is good-looking will marry someone who is also good-looking; a reader with more ordinary looks will marry someone who also fits that description; and a reader who is somewhere between good-looking and ordinary-looking will marry someone who also falls in the middle of the spectrum.

Naturally, these predictions will prove wrong for some readers. However, when one takes into account all the attributes listed (race, height, age, social class, appearance), the predictions will be right much more often than they are wrong, because people in the United States do in fact tend to choose mates fitting these general descriptions (Arum, Roksa, & Budig, 2008; Takeuchi, 2006).Arum, R., Josipa R., & Budig, M. J. (2008). The romance of college attendance: Higher education stratification and mate selection. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 26, 107–121; Alexander, T. S. (2006). On the matching phenomenon in courtship: A probability matching theory of mate selection. Marriage & Family Review, 40, 25–51. If most people will marry the type of person who has just been predicted for them, this may mean that, practically speaking, one’s choice of spouse is restricted—much more than we might like to admit—by social class, race, age, height, appearance, and other traits. If so, the choice of a mate is not as free as we might like to think it is.

For another example, take the right to vote. The secret ballot is one of the most cherished principles of American democracy. We vote in secret so that our choice of a candidate is made freely and without fear of punishment. That is all true, but it is also possible to predict the candidate for whom any one individual will vote if enough is known about the individual. Again, our choice (in this case, our choice of a candidate) is affected by many aspects of our social backgrounds and, in this sense, is not made as freely as we might think.

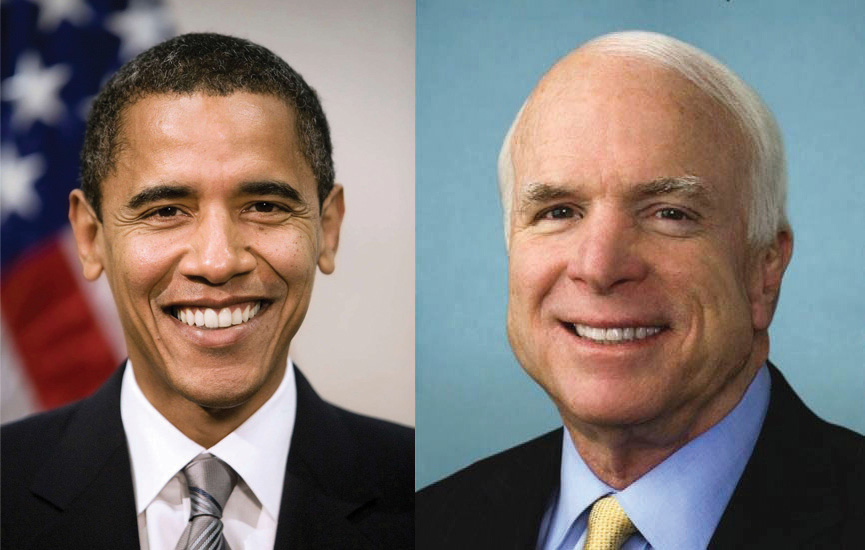

To illustrate this point, consider the 2008 presidential election between Democrat Barack Obama and Republican John McCain. Suppose a room is filled with 100 randomly selected voters from that election. Nothing is known about them except that they were between 18 and 24 years of age when they voted. Because exit poll data found that Obama won 66% of the vote from people in this age group (http://abcnews.go.com/PollingUnit/ExitPolls), a prediction that each of these 100 individuals voted for Obama would be correct about 66 times and incorrect only 34 times. Someone betting $1 on each prediction would come out $32 ahead ($66 – $34 = $32), even though the only thing known about the people in the room is their age.

Figure 1.1

Young people were especially likely to vote for Barack Obama in 2008, while white men tended, especially in Wyoming and several other states, to vote for John McCain. These patterns illustrate the influence of our social backgrounds on many aspects of our lives.

Source: Obama photo courtesy of the Obama-Biden Transition Project, http://change.gov/about/photo; McCain photo courtesy of the United States Congress, http://www.gpoaccess.gov/pictorial/111th/states/az.pdf.

Now let’s suppose we have a room filled with 100 randomly selected white men from Wyoming who voted in 2008. We know only three things about them: their race, gender, and state of residence. Because exit poll data found that 67% of white men in Wyoming voted for McCain, a prediction can be made with fairly good accuracy that these 100 men tended to have voted for McCain. Someone betting $1 that each man in the room voted for McCain would be right about 67 times and wrong only 33 times and would come out $34 ahead ($67 – $33 = $34). Even though young people in the United States and white men from Wyoming had every right and freedom under our democracy to vote for whomever they wanted in 2008, they still tended to vote for a particular candidate because of the influence of their age (in the case of the young people) or of their gender, race, and state of residence (white men from Wyoming).

Yes, Americans have freedom, but our freedom to think and act is constrained at least to some degree by society’s standards and expectations and by the many aspects of our social backgrounds. This is true for the kinds of important beliefs and behaviors just discussed, and it is also true for less important examples. For instance, think back to the last class you attended. How many of the women wore evening gowns? How many of the men wore skirts? Students are “allowed” to dress any way they want in most colleges and universities (as long as they do not go to class naked), but notice how few students, if any, dress in the way just mentioned. They do not dress that way because of the strange looks and even negative reactions they would receive.

Think back to the last time you rode in an elevator. Why did you not face the back? Why did you not sit on the floor? Why did you not start singing? Children can do these things and “get away with it,” because they look cute doing so, but adults risk looking odd. Because of that, even though we are “allowed” to act strangely in an elevator, we do not.

The basic point is that society shapes our attitudes and behavior even if it does not determine them altogether. We still have freedom, but that freedom is limited by society’s expectations. Moreover, our views and behavior depend to some degree on our social location in society—our gender, race, social class, religion, and so forth. Thus society as a whole and also our own social backgrounds affect our attitudes and behaviors. Our social backgrounds also affect one other important part of our lives, and that is our life chancesThe degree to which people succeed in life in such areas as education, income, and health.—our chances (whether we have a good chance or little chance) of being healthy, wealthy, and well educated and, more generally, of living a good, happy life.

The influence of our social environmentA general term for social backgrounds and other aspects of society. in all of these respects is the fundamental understanding that sociologyThe scientific study of social behavior and social institutions.—the scientific study of social behavior and social institutions—aims to present. At the heart of sociology is the sociological perspectiveThe belief that people’s social backgrounds influence their attitudes, behaviors, and life chances., the view that our social backgrounds influence our attitudes, behavior, and life chances. In this regard, we are not just individuals but rather social beings deeply enmeshed in society. Although we all differ from one another in many respects, we share with many other people basic aspects of our social backgrounds, perhaps especially gender, race and ethnicity, and social class. These shared qualities make us more similar to each other than we would otherwise be.

Does societyA group of people who live within a defined territory and who share a culture. totally determine our beliefs, behavior, and life chances? No. Individual differences still matter, and disciplines such as psychology are certainly needed for the most complete understanding of human action and beliefs. But if individual differences matter, so do society and the social backgrounds from which we come. Even the most individual attitudes and behaviors, such as the marriage and voting decisions discussed earlier, are influenced to some degree by our social backgrounds and, more generally, by the society to which we belong.

In this regard, consider what is perhaps the most personal decision one could make: the decision to take one’s own life. What could be more personal and individualistic than this fatal decision? When individuals commit suicide, we usually assume that they were very unhappy, even depressed. They may have been troubled by a crumbling romantic relationship, bleak job prospects, incurable illness, or chronic pain. But not all people in these circumstances commit suicide; in fact, few do. Perhaps one’s chances of committing suicide depend at least in part on various aspects of the person’s social background.

Figure 1.2

Although suicide is popularly considered to be a very individualistic act, it is also true that individuals’ likelihood of committing suicide depends at least partly on various aspects of their social backgrounds.

© Thinkstock

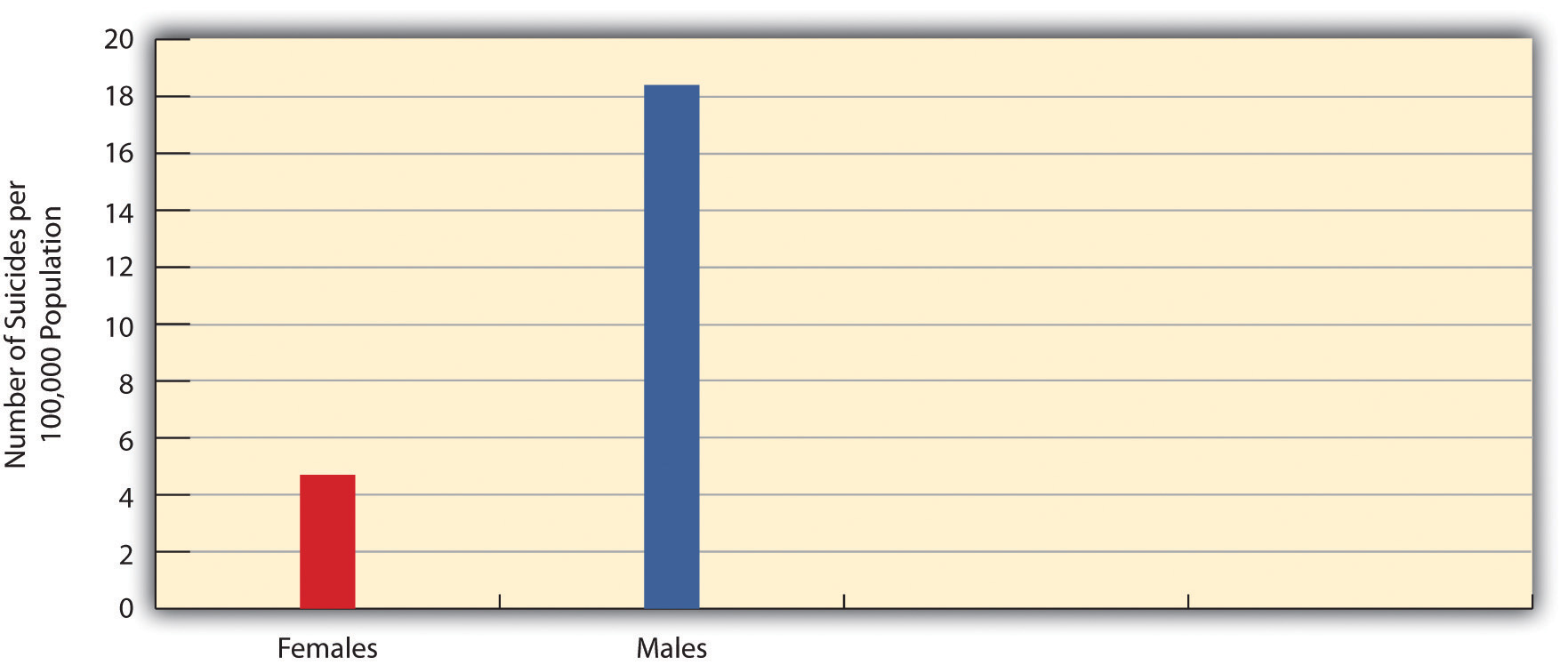

To illustrate this point, consider suicide rates—the percentage of a particular group of people who commit suicide, usually taken as, say, eight suicides for every 100,000 people in that group. Different groups have different suicide rates. As just one example, men are more likely than women to commit suicide (Figure 1.3 "Gender and Suicide Rate, 2007"). Why is this? Are men more depressed than women? No, the best evidence indicates that women are more depressed than men (Klein, Corwin, & Ceballos, 2006)Klein, L. C., Corwin, E. J., & Ceballos, R. M. (2006). The social costs of stress: How sex differences in stress responses can lead to social stress vulnerability and depression in women. In C. L. M. Keyes & S. H. Goodman (Eds.), Women and depression: A handbook for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences (pp. 199–218). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. and that women try to commit suicide more often than men (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008).Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2008). Suicide: Facts at a glance. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/ Suicide-DataSheet-a.pdf If so, there must be something about being a man that makes it more likely that males’ suicide attempts will result in death. One of these “somethings” is that males are more likely than females to try to commit suicide with a firearm, a far more lethal method than, say, taking an overdose of sleeping pills (Miller & Hemenway, 2008).Miller, M., & Hemenway. D. (2008). Guns and suicide in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 359, 989–991. If this is true, then it is fair to say that gender influences our chances of committing suicide, even if suicide is perhaps the most personal of all acts.

Figure 1.3 Gender and Suicide Rate, 2007

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau, 2010.

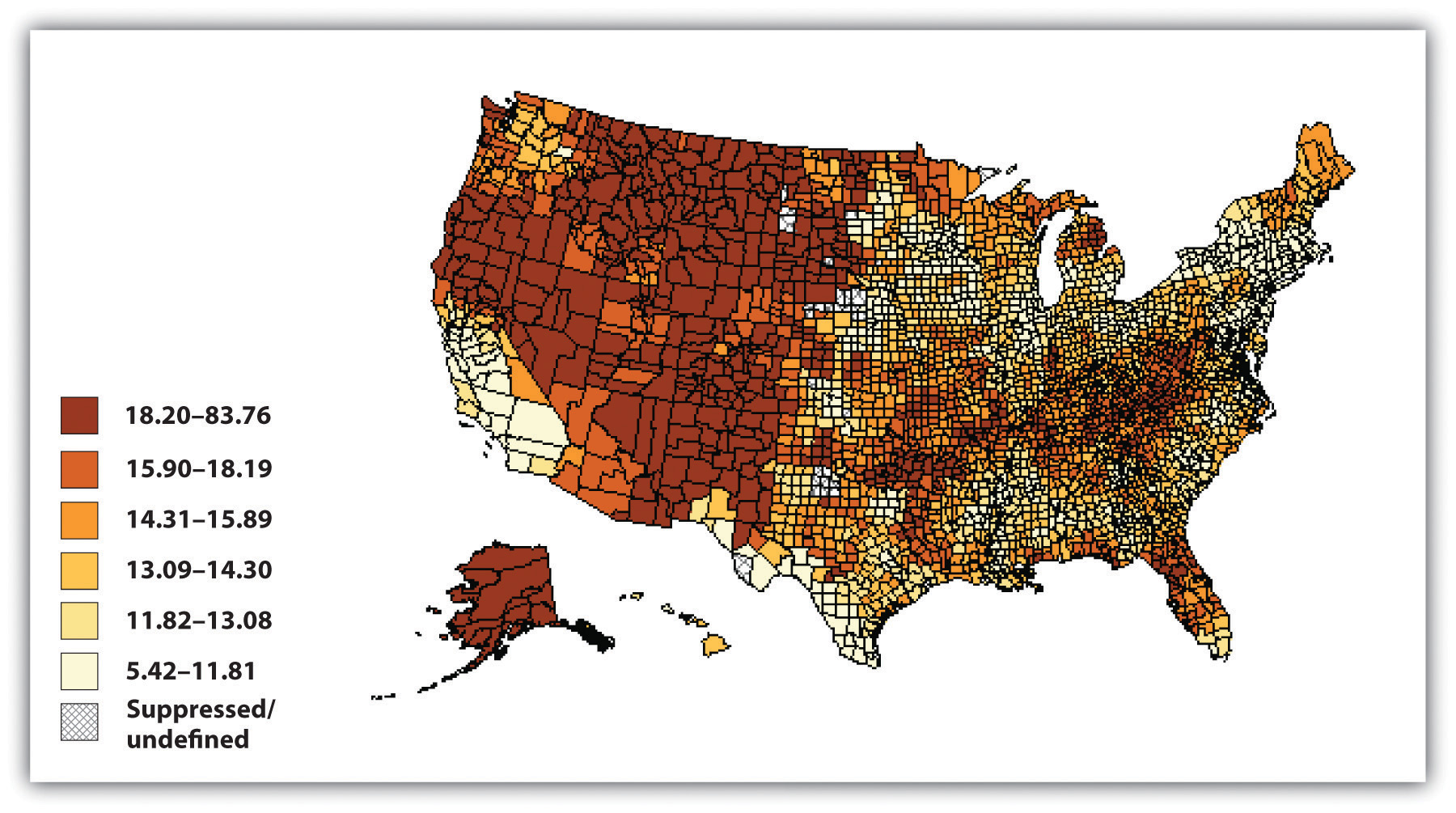

In the United States, suicide rates are generally higher west of the Mississippi River than east of it (Figure 1.4 "U.S. Suicide Rates, 2000–2006 (Number of Suicides per 100,000 Population)"). Is that because people out west are more depressed than those back east? No, there is no evidence of this. Perhaps there is something else about the western states that helps lead to higher suicide rates. For example, many of these states are sparsely populated compared to their eastern counterparts, with people in the western states living relatively far from one another. Because we know that social support networks help people deal with personal problems and deter possible suicides (Stack, 2000),Stack, S. (2000). Sociological research into suicide. In D. Lester (Ed.), Suicide prevention: Resources for the millennium (pp. 17–30). New York, NY: Routledge. perhaps these networks are weaker in the western states, helping lead to higher suicide rates. Then too, membership in organized religion is lower out west than back east (Finke & Stark, 2005).Finke, R., & Stark, S. (2005). The churching of America: Winners and losers in our religious economy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. If religious beliefs and the social support networks we experience from attending religious services both help us deal with personal problems, perhaps suicide rates are higher out west in part because religious belief is weaker. A depressed person out west thus is, all other things being equal, at least a little more likely than a depressed person back east to commit suicide.

Figure 1.4 U.S. Suicide Rates, 2000–2006 (Number of Suicides per 100,000 Population)

Source: Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. (2009). National suicide statistics at a glance. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide/statistics/suicide_map.html.

Key Takeaways

- According to the sociological perspective, social backgrounds influence attitudes, behavior, and life chances.

- Social backgrounds influence but do not totally determine attitudes and behavior.

- Americans may be less “free” in their thoughts and behavior than they normally think they are.

For Your Review

- Do you think that society constrains our thoughts and behaviors as the text argues? Why or why not?

- Describe how one aspect of your own social background has affected an important attitude you hold, a behavior in which you have engaged, or your ability to do well in life (life chances).

1.2 Sociology as a Social Science

Learning Objectives

- Explain what is meant by the sociological imagination.

- State the difference between the approach of blaming the system and that of blaming the victim.

- Describe what is meant by public sociology, and show how it relates to the early history of sociology in the United States.

Notice that we have been talking in generalizations. For example, the statement that men are more likely than women to commit suicide does not mean that every man commits suicide and no woman commits suicide. It means only that men have a higher suicide rate, even though most men, of course, do not commit suicide. Similarly, the statement that young people were more likely to vote for Obama than for McCain in 2008 does not mean that all young people voted for Obama; it means only that they were more likely than not to do so.

A generalizationA conclusion drawn from sociological research that is meant to apply to broad categories of people but for which many exceptions will always exist. in sociology is a general statement regarding a trend between various dimensions of our lives: gender and suicide rate, race and voting choice, and so forth. Many people will not fit the pattern of such a generalization, because people are shaped but not totally determined by their social environment. That is both the fascination and the frustration of sociology. Sociology is fascinating because no matter how much sociologists are able to predict people’s behavior, attitudes, and life chances, many people will not fit the predictions. But sociology is frustrating for the same reason. Because people can never be totally explained by their social environment, sociologists can never completely understand the sources of their behavior, attitudes, and life chances.

In this sense, sociology as a social science is very different from a discipline such as physics, in which known lawsIn the physical sciences, a statement of physical processes for which no exceptions are possible. exist for which no exceptions are possible. For example, we call the law of gravity a law because it describes a physical force that exists on the earth at all times and in all places and that always has the same result. If you were to pick up the book you are now reading or the computer or other device on which you are reading or listening to it and then let go, the object you were holding would obviously fall to the ground. If you did this a second time, it would fall a second time. If you did this a billion times, it would fall a billion times. In fact, if there were even one time out of a billion that your book or electronic device did not fall down, our understanding of the physical world would be totally revolutionized, the earth could be in danger, and you could go on television and make a lot of money.

For better or worse, people and social institutions—the subject matter of sociology—do not always follow our predictions. They are not like that book or electronic device that keeps falling down. People have their own minds, and social institutions their own reality, that often defy any effort to explain. Sociology can help us understand the social forces that affect our behavior, beliefs, and life chances, but it can only go so far. That limitation conceded, sociological understanding can still go fairly far toward such an understanding, and it can help us comprehend who we are and what we are by helping us first understand the profound yet often subtle influence of our social backgrounds on so many things about us.

Figure 1.5

People’s attitudes, behavior, and life chances are influenced but not totally determined by many aspects of their social environment.

© Thinkstock

Although sociology as a discipline is very different from physics, it is not as different as one might think from this and the other “hard” sciences. Like these disciplines, sociology as a social science relies heavily on systematic research that follows the standard rules of the scientific method. We return to these rules and the nature of sociological research later in this chapter. Suffice it to say here that careful research is essential for a sociological understanding of people, social institutions, and society.

At this point a reader might be saying, “I already know a lot about people. I could have told you that young people voted for Obama. I already had heard that men have a higher suicide rate than women. Maybe our social backgrounds do influence us in ways I had not realized, but what beyond that does sociology have to tell me?”

Students often feel this way because sociology deals with matters already familiar to them. Just about everyone has grown up in a family, so we all know something about it. We read a lot in the media about topics like divorce and health care, so we all already know something about these, too. All this leads some students to wonder if they will learn anything in their introduction to sociology course that they do not already know.

How Do We Know What We Think We Know?

Let’s consider this issue a moment: how do we know what we think we know? Our usual knowledge and understanding of social reality come from at least five sources: (a) personal experience; (b) common sense; (c) the media (including the Internet); (d) “expert authorities,” such as teachers, parents, and government officials; and (e) tradition. These are all important sources of our understanding of how the world “works,” but at the same time their value can often be very limited.

Let’s look at them separately by starting with personal experience. Although personal experiences are very important, not everyone has the same personal experience. This obvious fact casts some doubt on the degree to which our personal experiences can help us understand everything there is to know about a topic and the degree to which we can draw conclusions from our personal experiences that necessarily apply to other people. For example, say you grew up in Maine or Vermont, where more than 98% of the population is white. If you relied on your personal experience to calculate how many people of color live in the country, you would conclude that almost everyone in the United States is also white, which obviously is not true. As another example, say you grew up in a family where your parents had the proverbial perfect marriage, as they loved each other deeply and rarely argued. If you relied on your personal experience to understand the typical American marriage, you would conclude that most marriages were as good as your parents’ marriage, which, unfortunately, also is not true. Many other examples could be cited here, but the basic point should be clear: although personal experience is better than nothing, it often offers only a very limited understanding of social reality other than our own.

If personal experience does not help that much when it comes to making predictions, what about common sense? Although common sense can be very helpful, it can also contradict itself. For example, which makes more sense, haste makes waste or he or she who hesitates is lost? How about birds of a feather flock together versus opposites attract? Or two heads are better than one versus too many cooks spoil the broth? Each of these common sayings makes sense, but if sayings that are opposite of each other both make sense, where does the truth lie? Can common sense always be counted on to help us understand social life? Slightly more than five centuries ago, everyone “knew” the earth was flat—it was just common sense that it had to be that way. Slightly more than a century ago, some of the leading physicians in the United States believed that women should not go to college because the stress of higher education would disrupt their menstrual cycles (Ehrenreich & English, 1979).Ehrenreich, B., & English, D. (1979). For her own good: 150 years of the experts’ advice to women. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books. If that bit of common sense(lessness) were still with us, many of the women reading this book would not be in college.

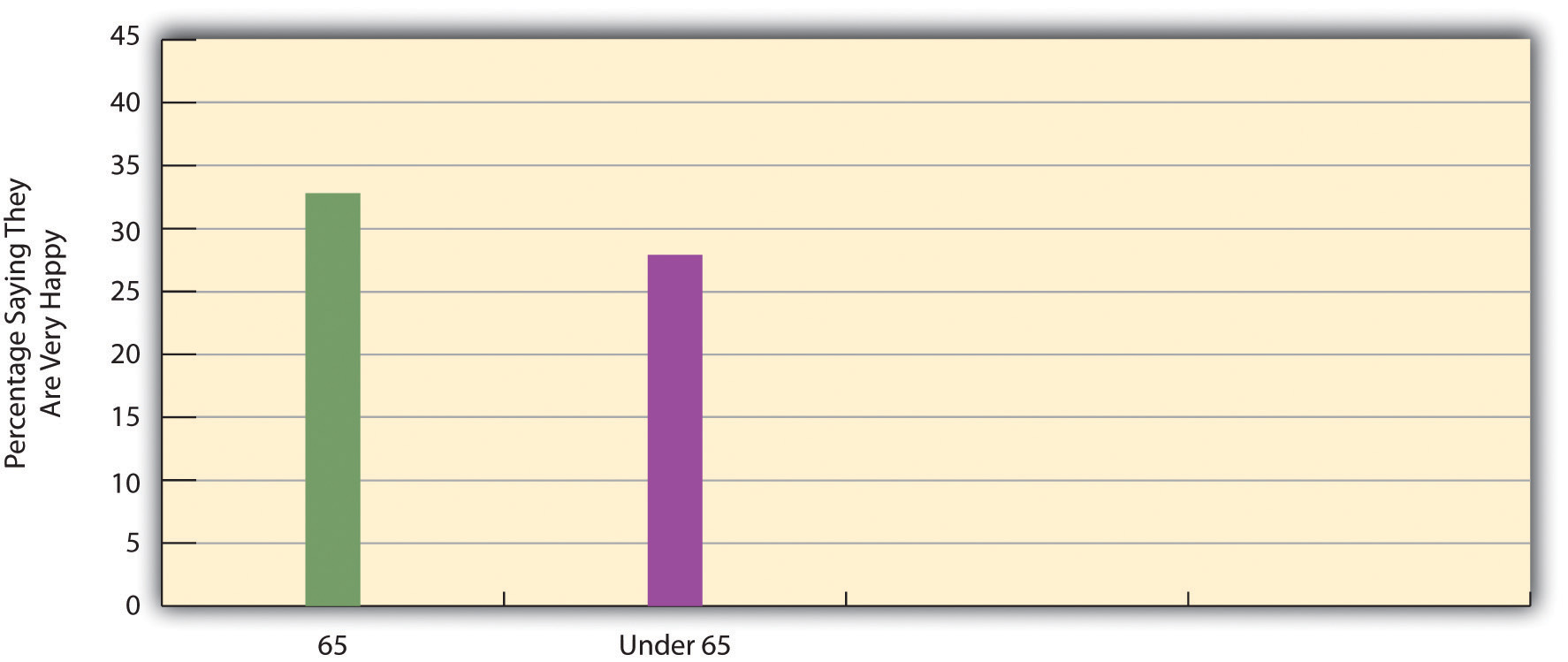

Still, perhaps there are some things that make so much sense they just have to be true; if sociology then tells us that they are true, what have we learned? Here is an example of such an argument. We all know that older people—those 65 or older—have many more problems than younger people. First, their health is generally worse. Second, physical infirmities make it difficult for many elders to walk or otherwise move around. Third, many have seen their spouses and close friends pass away and thus live lonelier lives than younger people. Finally, many are on fixed incomes and face financial difficulties. All of these problems indicate that older people should be less happy than younger people. If a sociologist did some research and then reported that older people are indeed less happy than younger people, what have we learned? The sociologist only confirmed the obvious.

The trouble with this confirmation of the obvious is that the “obvious” turns out not to be true after all. In the 2010 General Social Survey, which was given to a national random sample of Americans, respondents were asked, “Taken all together, how would you say things are these days? Would you say that you are very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?” Respondents aged 65 or older were actually slightly more likely than those younger than 65 to say they were very happy! About 33% of older respondents reported feeling this way, compared with only 28% of younger respondents (see Figure 1.6 "Age and Happiness"). What we all “knew” was obvious from common sense turns out not to have been so obvious after all.

Figure 1.6 Age and Happiness

Source: Data from General Social Survey, 2010.

If personal experience and common sense do not always help that much, how about the media? We learn a lot about current events and social and political issues from the Internet, television news, newspapers and magazines, and other media sources. It is certainly important to keep up with the news, but media coverage may oversimplify complex topics or even distort what the best evidence from systematic research seems to be telling us. A good example here is crime. Many studies show that the media sensationalize crime and suggest there is much more violent crime than there really is. For example, in the early 1990s, the evening newscasts on the major networks increased their coverage of murder and other violent crimes, painting a picture of a nation where crime was growing rapidly. The reality was very different, however, as crime was actually declining. The view that crime was growing was thus a myth generated by the media (Kurtz, 1997).Kurtz, H. (1997, August 12). The crime spree on network news. The Washington Post, p. D1.

Expert authorities, such as teachers, parents, and government officials, are a fourth source that influences our understanding of social reality. We learn much from our teachers and parents and perhaps from government officials, but, for better or worse, not all of what we learn from these sources about social reality is completely accurate. Teachers and parents do not always have the latest research evidence at their fingertips, and various biases may color their interpretation of any evidence with which they are familiar. As many examples from U.S. history illustrate, government officials may simplify or even falsify the facts. We should perhaps always listen to our teachers and parents and maybe even to government officials, but that does not always mean they give us a true, complete picture of social reality.

Figure 1.7

The news media often oversimplify complex topics and in other respects provide a misleading picture of social reality. As one example, news coverage sensationalizes violent crime and thus suggests that such crime is more common than it actually is.

© Thinkstock

A final source that influences our understanding of social reality is tradition, or long-standing ways of thinking about the workings of society. Tradition is generally valuable, because a society should always be aware of its roots. However, traditional ways of thinking about social reality often turn out to be inaccurate and incomplete. For example, traditional ways of thinking in the United States once assumed that women and people of color were biologically and culturally inferior to men and whites. Although some Americans continue to hold these beliefs, as we shall see in later chapters, these traditional assumptions have given way to more egalitarian assumptions. As we shall also see in later chapters, most sociologists certainly do not believe that women and people of color are biologically and culturally inferior.

If we cannot always trust personal experience, common sense, the media, expert authorities, and tradition to help us understand social reality, then the importance of systematic research gathered by sociology and the other social sciences becomes apparent. Although sociology sometimes does confirm the obvious, often it also confirms the nonobvious and even challenges conventional understandings of how society works and of controversial social issues. This emphasis is referred to as the debunking motif, to which we now turn.

The Debunking Motif

As Peter L. Berger (1963, pp. 23–24)Berger, P. L. (1963). Invitation to sociology: A humanistic perspective. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books. notes in his classic book Invitation to Sociology, “The first wisdom of sociology is this—things are not what they seem.” Social reality, he says, has “many layers of meaning,” and a goal of sociology is to help us discover these multiple meanings. He continues, “People who like to avoid shocking discoveries, who prefer to believe that society is just what they were taught in Sunday School…should stay away from sociology.”

This is because sociology helps us see through conventional understandings of how society works. Berger refers to this theme of sociology as the debunking motifFrom Peter L. Berger, a theme of sociology in which the aim is to go beyond superficial understandings of social reality.. By “looking for levels of reality other than those given in the official interpretations of society” (p. 38),Berger, P. L. (1963). Invitation to sociology: A humanistic perspective. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books. Berger says, sociology looks beyond on-the-surface understandings of social reality and helps us recognize the value of alternative understandings. In this manner, sociology often challenges conventional understandings about social reality and social institutions.

For example, suppose two people meet at a college mixer, or dance. They are interested in getting to know each other. What would be an on-the-surface understanding and description of their interaction over the next few minutes? What do they say? If they are like a typical couple who just met, they will ask questions like, What’s your name? Where are you from? What dorm do you live in? What’s your major? Now, such a description of their interaction is OK as far as it goes, but what is really going on here? Does either of the two people really care that much about the other person’s answers to these questions? Isn’t each one more concerned about how the other person is responding, both verbally and nonverbally, during this brief interaction? Is the other person paying attention and even smiling? Isn’t this kind of understanding a more complete analysis of these few minutes of interaction than an understanding based solely on the answers to questions like, What’s your major? For the most complete understanding of this brief encounter, then, we must look beyond the rather superficial things the two people are telling each other to uncover the true meaning of what is going on.

As another example, consider the power structure in a city or state. To know who has the power to make decisions, we would probably consult a city or state charter or constitution that spells out the powers of the branches of government. This written document would indicate who makes decisions and has power, but what would it not talk about? To put it another way, who or what else has power to influence the decisions elected officials make? Big corporations? Labor unions? The media? Lobbying groups representing all sorts of interests? The city or state charter or constitution may indicate who has the power to make decisions, but this understanding would be limited unless one looks beyond these written documents to get a deeper, more complete understanding of how power really operates in the setting being studied.

Social Structure and the Sociological Imagination

One way sociology achieves a more complete understandng of social reality is through its focus on the importance of the social forces affecting our behavior, attitudes, and life chances. This focus involves an emphasis on social structureThe social patterns through which society is organized., the social patterns through which a society is organized. Social structure can be both horizontal or vertical. Horizontal social structureThe social relationships and social and physical characteristics of communities to which individuals belong. refers to the social relationships and the social and physical characteristics of communities to which individuals belong. Some people belong to many networks of social relationships, including groups like the PTA and the Boy or Girl Scouts, while other people have fewer such networks. Some people grew up on streets where the houses were crowded together, while other people grew up in areas where the homes were much farther apart. These are examples of the sorts of factors constituting the horizontal social structure that forms such an important part of our social environment and backgrounds.

The other dimension of social structure is vertical. Vertical social structureA term used interchangeably with social inequality., more commonly called social inequalityThe unequal distribution of resources, such as wealth, that a society values., refers to ways in which a society or group ranks people in a hierarchy, with some more “equal” than others. In the United States and most other industrial societies, such things as wealth, power, race and ethnicity, and gender help determine one’s social ranking, or position, in the vertical social structure. Some people are at the top of society, while many more are in the middle or at the bottom. People’s positions in society’s hierarchy in turn often have profound consequences for their attitudes, behaviors, and life chances, both for themselves and for their children.

In recognizing the importance of social structure, sociology stresses that individual problems are often rooted in problems stemming from the horizontal and vertical social structures of society. This key insight informed C. Wright Mills’s (1959)Mills, C. W. (1959). The sociological imagination. London, England: Oxford University Press. classic distinction between personal troublesC. Wright Mills’s term for the personal problems that many individuals experience. and public issuesC. Wright Mills’s term for problems in society that underlie personal troubles.. Personal troubles refer to a problem affecting individuals that the affected individual, as well as other members of society, typically blame on the individual’s own failings. Examples include such different problems as eating disorders, divorce, and unemployment. Public issues, whose source lies in the social structure and culture of a society, refer to a social problem affecting many individuals. Thus problems in society help account for problems that individuals experience. Mills, feeling that many problems ordinarily considered private troubles are best understood as public issues, coined the term sociological imaginationFrom C. Wright Mills, the realization that personal troubles are rooted in public issues. to refer to the ability to appreciate the structural basis for individual problems.

To illustrate Mills’s viewpoint, let’s use our sociological imaginations to understand some important contemporary social problems. We will start with unemployment, which Mills himself discussed. If only a few people were unemployed, Mills wrote, we could reasonably explain their unemployment by saying they were lazy, lacked good work habits, and so forth. If so, their unemployment would be their own personal trouble. But when millions of people are out of work, unemployment is best understood as a public issue because, as Mills (1959, p. 9)Mills, C. W. (1959). The sociological imagination. London, England: Oxford University Press. put it, “the very structure of opportunities has collapsed. Both the correct statement of the problem and the range of possible solutions require us to consider the economic and political institutions of the society, and not merely the personal situation and character of a scatter of individuals.” The growing unemployment rate stemming from the severe economic downturn that began in 2008 provides a telling example of the point Mills was making. Millions of people lost their jobs through no fault of their own. While some individuals are undoubtedly unemployed because they are lazy or lack good work habits, a more structural explanation focusing on lack of opportunity is needed to explain why so many people were out of work as this book went to press. If so, unemployment is best understood as a public issue rather than a personal trouble.

Another contemporary problem is crime, which we explore further in Chapter 5 "Deviance, Crime, and Social Control". If crime were only a personal trouble, then we could blame crime on the moral failings of individuals, and many explanations of crime do precisely this. But such an approach ignores the fact that crime is a public issue, as structural factors such as inequality and the physical characteristics of communities contribute to high crime rates among certain groups in American society. As an illustration, consider identical twins separated at birth. One twin grows up in a wealthy suburb or rural area, while the other twin grows up in a blighted neighborhood in a poor, urban area. Twenty years later, which twin will be more likely to have a criminal record? You probably answered the twin growing up in the poor, run-down urban neighborhood. If so, you recognize that there is something about growing up in that type of neighborhood that increases the chances of a person becoming prone to crime. That “something” is the structural factors just mentioned. Criminal behavior is a public issue, not just a personal trouble.

Figure 1.8

Although eating disorders often stem from personal problems, they also may reflect a cultural emphasis for women to have slender bodies.

© Thinkstock

A final problem we will consider for now is eating disorders. We usually consider a person’s eating disorder to be a personal trouble that stems from a lack of control, low self-esteem, or other personal problem. This explanation may be OK as far as it goes, but it does not help us understand why so many people have the personal problems that lead to eating disorders. Perhaps more important, this belief also neglects the larger social and cultural forces that help explain such disorders. For example, most Americans with eating disorders are women, not men. This gender difference forces us to ask what it is about being a woman in American society that makes eating disorders so much more common. To begin to answer this question, we need to look to the standard of beauty for women that emphasizes a slender body (Whitehead & Kurz, 2008).Whitehead, K., & Kurz, T. (2008). Saints, sinners and standards of femininity: Discursive constructions of anorexia nervosa and obesity in women’s magazines. Journal of Gender Studies, 17, 345–358. If this cultural standard did not exist, far fewer American women would suffer from eating disorders than do now. Even if every girl and woman with an eating disorder were cured, others would take their places unless we could somehow change the cultural standard of female slenderness. To the extent this explanation makes sense, eating disorders are best understood as a public issue, not just as a personal trouble.

Picking up on Mills’s argument, William Ryan (1976)Ryan, W. (1976). Blaming the victim. New York, NY: Vintage Books. pointed out that Americans typically blame the victim when they think about the reasons for social problems such as poverty, unemployment, and crime. They feel that these problems stem from personal failings of the people suffering them, not from structural problems in the larger society. Using Mills’s terms, Americans tend to think of social problems as personal troubles rather than public issues. They thus subscribe to a blaming the victimThe belief that people experiencing difficulties are to blame for these problems. ideology rather than to a blaming the systemThe belief that personal difficulties stem from problems in society. belief.

To help us understand a blaming-the-victim ideology, let’s consider why poor children in urban areas often learn very little in their schools. A blaming-the-victim approach, according to Ryan, would say that the children’s parents do not care about their learning, fail to teach them good study habits, and do not encourage them to take school seriously. This type of explanation may apply to some parents, in Ryan’s opinion, but it ignores a much more important reason: the sad shape of America’s urban schools, which are decrepit structures housing old textbooks and out-of-date equipment. To improve the schooling of children in urban areas, he wrote, we must improve the schools themselves, and not just try to “improve” the parents.

As this example suggests, a blaming-the-victim approach points to solutions to social problems such as poverty and illiteracy that are very different from those suggested by a more structural approach that “blames the system.” If we blame the victim, we would spend our limited dollars to address the personal failings of individuals who suffer from poverty, illiteracy, poor health, eating disorders, and other difficulties. If instead we blame the system, we would focus our attention on the various social conditions (decrepit schools, cultural standards of female beauty, and the like) that account for these difficulties. A sociological perspective suggests that the latter approach is ultimately needed to help us deal successfully with the social problems facing us today.

Sociology and Social Reform: Public Sociology

This book’s subtitle is “understanding and changing the social world.” The last several pages were devoted to the subtitle’s first part, understanding. Our discussion of Mills’s and Ryan’s perspectives in turn points to the implications of a sociological understanding for changing the social world. This understanding suggests the need to focus on the structural and cultural factors and various problems in the social environment that help explain both social issues and private troubles, to recall Mills’s terms.

The use of sociological knowledge to achieve social reform was a key theme of sociology as it developed in the United States after emerging at the University of Chicago in the 1890s (Calhoun, 2007).Calhoun, C. (2007). Sociology in America: An introduction. In C. Calhoun (Ed.), Sociology in America: A history (pp. 1–38). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. The early Chicago sociologists aimed to use their research to achieve social reform and, in particular, to reduce poverty and its related effects. They worked closely with Jane Addams (1860–1935), a renowned social worker who founded Hull House (a home for the poor in Chicago) in 1899 and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931. Addams gained much attention for her analyses of poverty and other social problems of the time, and her book Twenty Years at Hull House remains a moving account of her work with the poor and ill in Chicago (Deegan, 1990).Deegan, M. J. (1990). Jane Addams and the men of the Chicago school, 1892–1918. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

About the same time, W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963), a sociologist and the first African American to obtain a PhD from Harvard University, wrote groundbreaking books and articles on race in American society and, more specifically, on the problems facing African Americans (Morris, 2007).Morris, A. D. (2007). Sociology of race and W. E. B. Du Bois: The path not taken. In C. Calhoun (Ed.), Sociology in America: A history (pp. 503–534). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. One of these works was his 1899 book The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study, which attributed the problems facing Philadelphia blacks to racial prejudice among whites. Du Bois also helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). A contemporary of Du Bois was Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862–1931), a former slave who became an activist for women’s rights and also worked tirelessly to improve the conditions of African Americans. She wrote several studies of lynching and joined Du Bois in helping to found the NAACP (Bay, 2009).Bay, M. (2009). To tell the truth freely: The life of Ida B. Wells. New York, NY: Hill and Wang.

American sociology has never fully lost its early calling, but by the 1940s and 1950s many sociologists had developed a more scientific, professional orientation that disregarded social reform (Calhoun, 2007).Calhoun, C. (2007). Sociology in America: An introduction. In C. Calhoun (Ed.), Sociology in America: A history (pp. 1–38). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. In 1951, a group of sociologists who felt that sociology had abandoned the discipline’s early social reform orientation formed a new national association, the Society for the Study of Social Problems (SSSP). SSSP’s primary aim today remains the use of sociological knowledge to achieve social justice (http://sssp1.org). During the 1960s, a new wave of young sociologists, influenced by the political events and social movements of that tumultuous period, again took up the mantle of social reform and clashed with their older colleagues. A healthy tension has existed since then between sociologists who see social reform as a major goal of their work and those who favor sociological knowledge for its own sake.

In 2004, the president of the American Sociological Association, Michael Burawoy, called for “public sociology,” or the use of sociological insights and findings to address social issues and achieve social change (Burawoy, 2005).Burawoy, M. (2005). 2004 presidential address: For public sociology. American Sociological Review, 70, 4–28. His call ignited much excitement and debate, as public sociology became the theme or prime topic of several national and regional sociology conferences and of special issues or sections of major sociological journals. Several sociology departments began degree programs or concentrations in public sociology, and a Google search of “public sociology” in June 2010 yielded 114,000 results. In the spirit of public sociology, the chapters that follow aim to show the relevance of sociological knowledge for social reform.

Key Takeaways

- Personal experience, common sense, and the mass media often yield inaccurate or incomplete understandings of social reality.

- The debunking motif involves seeing beyond taken-for-granted assumptions of social reality.

- According to C. Wright Mills, the sociological imagination involves the ability to recognize that private troubles are rooted in public issues and structural problems.

- Early U.S. sociologists emphasized the use of sociological research to achieve social reform, and today’s public sociology reflects the historical roots of sociology in this regard.

For Your Review

- Provide an example in which one of your own personal experiences probably led you to inaccurately understand social reality.

- Provide an example, not discussed in the text, of a taken-for-granted assumption of social reality that may be inaccurate or incomplete.

- Select an example of a “private trouble” and explain how and why it may reflect a structural problem in society.

- Do you think it is important to emphasize the potential use of sociological research to achieve social reform? Why or why not?

1.3 Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish macro approaches in sociology from micro approaches.

- Summarize the most important beliefs and assumptions of functionalism and conflict theory.

- Summarize the most important beliefs and assumptions of symbolic interactionism and exchange theory.

We have talked repeatedly about “a” sociological perspective, as if all sociologists share the same beliefs on how society works. This implication is misleading. Although all sociologists would probably accept the basic premise that social backgrounds affect people’s attitudes, behavior, and life chances, their views as sociologists differ in many other ways.

Macro and Micro Approaches

Although this may be overly simplistic, sociologists’ views basically fall into two camps: macrosociologyThat part of sociology that deals with issues involving large-scale social change and social institutions. and microsociologyThat part of sociology that deals with social interaction in small settings.. Macrosociologists focus on the big picture, which usually means such things as social structure, social institutions, and social, political, and economic change. They look at the large-scale social forces that change the course of human society and the lives of individuals. Microsociologists, on the other hand, study social interaction. They look at how families, coworkers, and other small groups of people interact; why they interact the way they do; and how they interpret the meanings of their own interactions and of the social settings in which they find themselves. Often macro- and microsociologists look at the same phenomena but do so in different ways. Their views taken together offer a fuller understanding of the phenomena than either approach can offer alone.

Figure 1.9

Microsociologists examine the interaction of small groups of people, such as the two women conversing here. These sociologists examine how and why individuals interact and interpret the meanings of their interaction.

© Thinkstock

The different but complementary nature of these two approaches can be seen in the case of armed robbery. Macrosociologists would discuss such things as why robbery rates are higher in poorer communities and whether these rates change with changes in the national economy. Microsociologists would instead focus on such things as why individual robbers decide to commit a robbery and how they select their targets. Both types of approaches give us a valuable understanding of robbery, but together they offer an even richer understanding.

Within the broad macro camp, two perspectives dominate: functionalism and conflict theory. Within the micro camp, two other perspectives exist: symbolic interactionism and utilitarianism (also called rational choice theory or exchange theory) (Collins, 1994).Collins, R. (1994). Four sociological traditions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. We now turn to these four theoretical perspectives, which are summarized in Table 1.1 "Theory Snapshot".

Table 1.1 Theory Snapshot

| Theoretical perspective | Major assumptions |

|---|---|

| Functionalism | Social stability is necessary to have a strong society, and adequate socialization and social integration are necessary to achieve social stability. Society’s social institutions perform important functions to help ensure social stability. Slow social change is desirable, but rapid social change threatens social order. Functionalism is a macro theory. |

| Conflict theory | Society is characterized by pervasive inequality based on social class, gender, and other factors. Far-reaching social change is needed to reduce or eliminate social inequality and to create an egalitarian society. Conflict theory is a macro theory. |

| Symbolic interactionism | People construct their roles as they interact; they do not merely learn the roles that society has set out for them. As this interaction occurs, individuals negotiate their definitions of the situations in which they find themselves and socially construct the reality of these situations. In so doing, they rely heavily on symbols such as words and gestures to reach a shared understanding of their interaction. Symbolic interactionism is a micro theory. |

| Utilitarianism (rational choice theory or exchange theory) | People act to maximize their advantages in a given situation and to reduce their disadvantages. If they decide that benefits outweigh disadvantages, they will initiate the interaction or continue it if it is already under way. If they instead decide that disadvantages outweigh benefits, they will decline to begin interacting or stop the interaction if already begun. Social order is possible because people realize it will be in their best interests to cooperate and to make compromises when necessary. Utilitarianism is a micro theory. |

Functionalism

FunctionalismThe view that social institutions are important for their contributions to social stability., also known as the functionalist perspective, arose out of two great revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries. The first was the French Revolution of 1789, whose intense violence and bloody terror shook Europe to its core. The aristocracy throughout Europe feared that revolution would spread to their own lands, and intellectuals feared that social order was crumbling.

The Industrial Revolution of the 19th century reinforced these concerns. Starting first in Europe and then in the United States, the Industrial Revolution led to many changes, including the rise and growth of cities as people left their farms to live near factories. As the cities grew, people lived in increasingly poor, crowded, and decrepit conditions. One result of these conditions was mass violence, as mobs of the poor roamed the streets of European and American cities. They attacked bystanders, destroyed property, and generally wreaked havoc. Here was additional evidence, if European intellectuals needed it, of the breakdown of social order.

In response, the intellectuals began to write that a strong society, as exemplified by strong social bonds and rules and effective socialization, was needed to prevent social order from disintegrating (Collins, 1994).Collins, R. (1994). Four sociological traditions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. In this regard, their view was similar to that of the 20th-century novel Lord of the Flies by William Golding (1954),Golding, W. (1954). Lord of the flies. London, England: Coward-McCann. which many college students read in high school. Some British boys are stranded on an island after a plane crash. No longer supervised by adults and no longer in a society as they once knew it, they are not sure how to proceed and come up with new rules for their behavior. These rules prove ineffective, and the boys slowly become savages, as the book calls them, and commit murder. However bleak, Golding’s view echoes back to that of the conservative intellectuals writing in the aftermath of the French and Industrial Revolutions. Without a strong society and effective socialization, they warned, social order breaks down, and violence and other signs of social disorder result.

This general framework reached fruition in the writings of Émile Durkheim (1858–1917), a French scholar largely responsible for the sociological perspective as we now know it. Adopting the conservative intellectuals’ view of the need for a strong society, Durkheim felt that human beings have desires that result in chaos unless society limits them. He wrote, “To achieve any other result, the passions first must be limited.…But since the individual has no way of limiting them, this must be done by some force exterior to him” (Durkheim, 1897/1952, p. 274).Durkheim, E. (1952). Suicide. New York, NY: Free Press. (Original work published 1897) This force, Durkheim continued, is the moral authority of society.

How does society limit individual aspirations? Durkheim emphasized two related social mechanisms: socialization and social integration. Socialization helps us learn society’s rules and the need to cooperate, as people end up generally agreeing on important norms and values, while social integration, or our ties to other people and to social institutions such as religion and the family, helps to socialize us and to integrate us into society and reinforce our respect for its rules. In general, Durkheim added, society comprises many types of social facts, or forces external to the individual, that affect and constrain individual attitudes and behavior. The result is that socialization and social integration help establish a strong set of social rules—or, as Durkheim called it, a strong collective conscienceFrom Émile Durkheim, the combined norms of society.—that is needed for a stable society. By so doing, society “creates a kind of cocoon around the individual, making him or her less individualistic, more a member of the group” (Collins, 1994, p. 181).Collins, R. (1994). Four sociological traditions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Weak rules or social ties weaken this “moral cocoon” and lead to social disorder. In all of these respects, says Randall Collins (1994, p. 181),Collins, R. (1994). Four sociological traditions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Durkheim’s view represents the “core tradition” of sociology that lies at the heart of the sociological perspective.

Figure 1.10

Émile Durkheim was a founder of sociology and largely responsible for the sociological perspective as we now know it.

Source: Photo courtesy of http://www.marxists.org/glossary/people/d/pics/durkheim.jpg.

Durkheim used suicide to illustrate how social disorder can result from a weakening of society’s moral cocoon. Focusing on group rates of suicide, he felt they could not be explained simply in terms of individual unhappiness and instead resulted from external forces. One such force is anomieNormlessness, a state in which social norms are unclear., or normlessness, which results from situations, such as periods of rapid social change, when social norms are weak and unclear or social ties are weak. When anomie sets in, people become more unclear about how to deal with problems in their life. Their aspirations, no longer limited by society’s constraints, cannot be fulfilled. The frustration stemming from anomie leads some people to commit suicide (Durkheim, 1897/1952).Durkheim, E. (1952). Suicide. New York, NY: Free Press. (Original work published 1897)

To test his theory, Durkheim gathered suicide rate data and found that Protestants had higher suicide rates than Catholics. To explain this difference, he rejected the idea that Protestants were less happy than Catholics and instead reasoned that Catholic doctrine provides many more rules for behavior and thinking than does Protestant doctrine. Protestants’ aspirations were thus less constrained than Catholics’ desires. In times of trouble, Protestants also have fewer norms on which to rely for comfort and support than do Catholics. He also thought that Protestants’ ties to each other were weaker than those among Catholics, providing Protestants fewer social support networks to turn to when troubled. In addition, Protestant belief is ambivalent about suicide, while Catholic doctrine condemns it. All of these properties of religious group membership combine to produce higher suicide rates among Protestants than among Catholics.

Today’s functionalist perspective arises out of Durkheim’s work and that of other conservative intellectuals of the 19th century. It uses the human body as a model for understanding society. In the human body, our various organs and other body parts serve important functions for the ongoing health and stability of our body. Our eyes help us see, our ears help us hear, our heart circulates our blood, and so forth. Just as we can understand the body by describing and understanding the functions that its parts serve for its health and stability, so can we understand society by describing and understanding the functions that its “parts”—or, more accurately, its social institutions—serve for the ongoing health and stability of society. Thus functionalism emphasizes the importance of social institutions such as the family, religion, and education for producing a stable society. We look at these institutions in later chapters.

Similar to the view of the conservative intellectuals from which it grew, functionalism is skeptical of rapid social change and other major social upheaval. The analogy to the human body helps us understand this skepticism. In our bodies, any sudden, rapid change is a sign of danger to our health. If we break a bone in one of our legs, we have trouble walking; if we lose sight in both our eyes, we can no longer see. Slow changes, such as the growth of our hair and our nails, are fine and even normal, but sudden changes like those just described are obviously troublesome. By analogy, sudden and rapid changes in society and its social institutions are troublesome according to the functionalist perspective. If the human body evolved to its present form and functions because these made sense from an evolutionary perspective, so did society evolve to its present form and functions because these made sense. Any sudden change in society thus threatens its stability and future. By taking a skeptical approach to social change, functionalism supports the status quo and is thus often regarded as a conservative perspective.

Conflict Theory

In many ways, conflict theoryThe view that society is composed of groups with different interests arising from their placement in the social structure. is the opposite of functionalism but ironically also grew out of the Industrial Revolution, thanks largely to Karl Marx (1818–1883) and his collaborator, Friedrich Engels (1820–1895). Whereas conservative intellectuals feared the mass violence resulting from industrialization, Marx and Engels deplored the conditions they felt were responsible for the mass violence and the capitalist society they felt was responsible for these conditions. Instead of fearing the breakdown of social order that mass violence represented, they felt that revolutionary violence was needed to eliminate capitalism and the poverty and misery they saw as its inevitable result (Marx, 1867/1906; Marx & Engels, 1848/1962).Marx, K. 1906. Capital. New York, NY: Random House. (Original work published 1867); Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1962). The Communist Manifesto. In Marx and Engels: Selected works (pp. 21–65). Moscow, Russia: Foreign Language Publishing House. (Original work published 1848)

Figure 1.11

Karl Marx and his collaborator Friedrich Engels were intense critics of capitalism. Their work inspired the later development of conflict theory in sociology.

© Thinkstock

According to Marx and Engels, every society is divided into two classes based on the ownership of the means of production (tools, factories, and the like). In a capitalist society, the bourgeoisieThe ruling class., or ruling class, owns the means of production, while the proletariatThe working class., or working class, does not own the means of production and instead is oppressed and exploited by the bourgeoisie. This difference creates automatic conflict of interests between the two groups. Simply put, the bourgeoisie is interested in maintaining its position at the top of society, while the proletariat’s interest lies in rising up from the bottom and overthrowing the bourgeoisie to create an egalitarian society.

In a capitalist society, Marx and Engels wrote, revolution is inevitable because of structural contradictions arising from the very nature of capitalism. Because profit is the main goal of capitalism, the bourgeoisie’s interest lies in maximizing profit. To do so, capitalists try to keep wages as low as possible and to spend as little money as possible on working conditions. This central fact of capitalism, said Marx and Engels, eventually prompts the rise among workers of class consciousnessAwareness of one’s placement in the social structure and the interests arising from this placement., or an awareness of the reasons for their oppression. Their class consciousness in turn leads them to revolt against the bourgeoisie to eliminate the oppression and exploitation they suffer.

Over the years, Marx and Engels’s views on the nature of capitalism and class relations have greatly influenced social, political, and economic theory and also inspired revolutionaries in nations around the world. However, history has not supported their prediction that capitalism will inevitably result in a revolution of the proletariat. For example, no such revolution has occurred in the United States, where workers never developed the degree of class consciousness envisioned by Marx and Engels. Because the United States is thought to be a free society where everyone has the opportunity to succeed, even poor Americans feel that the system is basically just. Thus various aspects of American society and ideology have helped minimize the development of class consciousness and prevent the revolution that Marx and Engels foresaw.

Despite this shortcoming, their basic view of conflict arising from unequal positions held by members of society lies at the heart of today’s conflict theory. This theory emphasizes that different groups in society have different interests stemming from their different social positions. These different interests in turn lead to different views on important social issues. Some versions of the theory root conflict in divisions based on race and ethnicity, gender, and other such differences, while other versions follow Marx and Engels in seeing conflict arising out of different positions in the economic structure. In general, however, conflict theory emphasizes that the various parts of society contribute to ongoing inequality, whereas functionalist theory, as we have seen, stresses that they contribute to the ongoing stability of society. Thus, while functionalist theory emphasizes the benefits of the various parts of society for ongoing social stability, conflict theory favors social change to reduce inequality. In this regard, conflict theory may be considered a progressive perspective.

Feminist theoryThe view that society is filled with gender inequality characterized by women being the subordinate sex in the social, political, and economic dimensions of society. has developed in sociology and other disciplines since the 1970s and for our purposes will be considered a specific application of conflict theory. In this case, the conflict concerns gender inequality rather than the class inequality emphasized by Marx and Engels. Although many variations of feminist theory exist, they all emphasize that society is filled with gender inequality such that women are the subordinate sex in many dimensions of social, political, and economic life (Tong, 2009).Tong, R. (2009). Feminist thought: A more comprehensive introduction. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Liberal feminists view gender inequality as arising out of gender differences in socialization, while Marxist feminists say that this inequality is a result of the rise of capitalism, which made women dependent on men for economic support. On the other hand, radical feminists view gender inequality as present in all societies, not just capitalist ones. Chapter 8 "Gender and Gender Inequality" examines some of the arguments of feminist theory at great length.

Symbolic Interactionism

Whereas the functionalist and conflict perspectives are macro approaches, symbolic interactionismA micro perspective in sociology that focuses on the meanings people gain from social interaction. is a micro approach that focuses on the interaction of individuals and on how they interpret their interaction. Its roots lie in the work in the early 1900s of American sociologists, social psychologists, and philosophers who were interested in human consciousness and action. Herbert Blumer (1969),Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. a sociologist at the University of Chicago, built upon their writings to develop symbolic interactionism, a term he coined. This view remains popular today, in part because many sociologists object to what they perceive as the overly deterministic view of human thought and action and passive view of the individual inherent in the sociological perspective derived from Durkheim.

Drawing on Blumer’s work, symbolic interactionists feel that people do not merely learn the roles that society has set out for them; instead they construct these roles as they interact. As they interact, they “negotiate” their definitions of the situations in which they find themselves and socially construct the reality of these situations. In so doing, they rely heavily on symbols such as words and gestures to reach a shared understanding of their interaction.

An example is the familiar symbol of shaking hands. In the United States and many other societies, shaking hands is a symbol of greeting and friendship. This simple act indicates that you are a nice, polite person with whom someone should feel comfortable. To reinforce this symbol’s importance for understanding a bit of interaction, consider a situation where someone refuses to shake hands. This action is usually intended as a sign of dislike or as an insult, and the other person interprets it as such. Their understanding of the situation and subsequent interaction will be very different from those arising from the more typical shaking of hands.

Now let’s say that someone does not shake hands, but this time the reason is that the person’s right arm is broken. Because the other person realizes this, no snub or insult is inferred, and the two people can then proceed to have a comfortable encounter. Their definition of the situation depends not only on whether they shake hands but also, if they do not shake hands, on why they do not. As the term symbolic interactionism implies, their understanding of this encounter arises from what they do when they interact and their use and interpretation of the various symbols included in their interaction. According to symbolic interactionists, social order is possible because people learn what various symbols (such as shaking hands) mean and apply these meanings to different kinds of situations. If you visited a society where sticking your right hand out to greet someone was interpreted as a threatening gesture, you would quickly learn the value of common understandings of symbols.

Utilitarianism

UtilitarianismThe view that people interact so as to maximize their benefits and minimize their disadvantages. is a general view of human behavior that says people act to maximize their pleasure and to reduce their pain. It originated in the work of such 18th-century thinkers as the Italian economist Cesare Beccaria (1738–1794) and the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832). Both men thought that people act rationally and decide before they act whether their behavior will cause them more pleasure or pain. Applying their views to crime, they felt the criminal justice system in Europe at the time was far harsher than it needed to be to deter criminal behavior. Another 18th-century utilitarian thinker was Adam Smith, whose book The Wealth of Nations (1776/1910)Smith, A. (1910). The wealth of nations. London, England: J. M. Dent & Sons; New York, NY: E. P. Dutton. (Original work published 1776) laid the foundation for modern economic thought. Indeed, at the heart of economics is the view that sellers and buyers of goods and services act rationally to reduce their costs and in this and other ways to maximize their profits.

In sociology, utilitarianism is commonly called exchange theoryUtilitarianism. or rational choice theoryUtilitarianism. (Coleman, 1990; Homans, 1961).Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; Homans, G. (1961). Social behavior: Its elementary forms. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. No matter what name it goes under, this view emphasizes that when people interact, they seek to maximize the benefits they gain from the interaction and to reduce the disadvantages. If they decide that the interaction’s benefits outweigh its disadvantages, they will initiate the interaction or continue it if it is already under way. If they instead decide that the interaction’s disadvantages outweigh its benefits, they will decline to begin interacting or stop the interaction if already begun. Social order is possible because people realize it will be in their best interests to cooperate and to make compromises when necessary.

A familiar application of exchange theory would be a dating relationship. Each partner in a dating relationship gives up a bit of autonomy in return for love and other benefits of being close to someone. Yet every relationship has its good and bad moments, and both partners make frequent compromises to ensure the relationship will endure. As long as the couple feels the good moments outweigh the bad moments, the relationship will continue. But once one or both partners decide the reverse is true, the relationship will end.

Comparing Macro and Micro Perspectives

This brief presentation of the four major theoretical perspectives in sociology is necessarily incomplete but should at least outline their basic points. Each perspective has its proponents, and each has its detractors. All four offer a lot of truth, and all four oversimplify and make other mistakes. We will return to them in many of the chapters ahead, but a brief critique is in order here.

A major problem with functionalist theory is that it tends to support the status quo and thus seems to favor existing inequalities based on race, social class, and gender. By emphasizing the contributions of social institutions such as the family and education to social stability, functionalist theory minimizes the ways in which these institutions contribute to social inequality.

Conflict theory’s problems are the opposite of functionalist theory’s. By emphasizing inequality and dissensus in society, conflict theory overlooks the large degree of consensus on many important issues. And by emphasizing the ways in which social institutions contribute to social inequality, conflict theory minimizes the ways in which these institutions are necessary for society’s stability.

Neither of these two macro perspectives has very much to say about social interaction, one of the most important building blocks of society. In this regard, the two micro perspectives, symbolic interactionism and utilitarianism, offer significant advantages over their macro cousins. Yet their very micro focus leads them to pay relatively little attention to the reasons for, and possible solutions to, such broad and fundamentally important issues as poverty, racism, sexism, and social change, which are all addressed by functionalism and conflict theory. In this regard, the two macro perspectives offer significant advantages over their micro cousins. In addition, one of the micro perspectives, rational choice theory, has also been criticized for ignoring the importance of emotions, altruism, and other values for guiding human interaction (Lowenstein, 1996).Lowenstein, G. (1996). Out of control: Visceral influences on behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 65, 272–292.

Figure 1.12

To explain armed robbery, symbolic interactionists focus on how armed robbers decide when and where to rob a victim and on how their interactions with other criminals reinforce their own criminal tendencies.

© Thinkstock

These criticisms aside, all four perspectives taken together offer a more comprehensive understanding of social phenomena than any one perspective can offer alone. To illustrate this, let’s return to our armed robbery example. A functionalist approach might suggest that armed robbery and other crimes actually serve positive functions for society. As one function, fear of crime ironically strengthens social bonds by uniting the law-abiding public against the criminal elements in society. As a second function, armed robbery and other crimes create many jobs for police officers, judges, lawyers, prison guards, the construction companies that build prisons, and the various businesses that provide products the public buys to help protect against crime.

Conflict theory would take a very different but no less helpful approach to understanding armed robbery. It might note that most street criminals are poor and thus emphasize that armed robbery and other crimes are the result of the despair and frustration of living in poverty and facing a lack of jobs and other opportunities for economic and social success. The roots of street crime, from the perspective of conflict theory, thus lie in society at least as much as they lie in the individuals committing such crime.

In explaining armed robbery, symbolic interactionism would focus on how armed robbers make such decisions as when and where to rob someone and on how their interactions with other criminals reinforce their own criminal tendencies. Exchange or rational choice theory would emphasize that armed robbers and other criminals are rational actors who carefully plan their crimes and who would be deterred by a strong threat of swift and severe punishment.

Now that you have some understanding of the major theoretical perspectives in sociology, we’ll next see how sociologists go about testing these perspectives.

Key Takeaways

- Sociological theories may be broadly divided into macro approaches and micro approaches.

- Functionalism emphasizes the importance of social institutions for social stability and implies that far-reaching social change will be socially harmful.

- Conflict theory emphasizes social inequality and suggests that far-reaching social change is needed to achieve a just society.

- Symbolic interactionism emphasizes the social meanings and understandings that individuals derive from their social interaction.

- Utilitarianism emphasizes that people act in their self-interest by calculating whether potential behaviors will be more advantageous than disadvantageous.

For Your Review

- In thinking about how you view society and individuals, do you consider yourself more of a macro thinker or a micro thinker?

- At this point in your study of sociology, which one of the four sociological traditions sounds most appealing to you? Why?

1.4 Doing Sociological Research

Learning Objectives

- Describe the different types of units of analysis in sociology.

- Explain the difference between an independent variable and a dependent variable.

- List the major advantages and disadvantages of surveys, observational studies, and experiments.

- Discuss an example of a sociological study that raised ethical issues.

Research is an essential component of the social, natural, and physical sciences. This section briefly describes the elements and types of sociological research.