This is “Analysis of Survey Data”, section 8.5 from the book Sociological Inquiry Principles: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

8.5 Analysis of Survey Data

Learning Objectives

- Define response rate, and discuss some of the current thinking about response rates.

- Describe what a codebook is and what purpose it serves.

- Define univariate, bivariate, and multivariate analysis.

- Describe each of the measures of central tendency.

- Describe what a contingency table displays.

This text is primarily focused on designing research, collecting data, and becoming a knowledgeable and responsible consumer of research. We won’t spend as much time on data analysis, or what to do with our data once we’ve designed a study and collected it, but I will spend some time in each of our data-collection chapters describing some important basics of data analysis that are unique to each method. Entire textbooks could be (and have been) written entirely on data analysis. In fact, if you’ve ever taken a statistics class, you already know much about how to analyze quantitative survey data. Here we’ll go over a few basics that can get you started as you begin to think about turning all those completed questionnaires into findings that you can share.

From Completed Questionnaires to Analyzable Data

It can be very exciting to receive those first few completed surveys back from respondents. Hopefully you’ll even get more than a few back, and once you have a handful of completed questionnaires, your feelings may go from initial euphoria to dread. Data are fun and can also be overwhelming. The goal with data analysis is to be able to condense large amounts of information into usable and understandable chunks. Here we’ll describe just how that process works for survey researchers.

As mentioned, the hope is that you will receive a good portion of the questionnaires you distributed back in a completed and readable format. The number of completed questionnaires you receive divided by the number of questionnaires you distributed is your response rateThe percentage of completed questionnaires returned; determined by dividing the number of completed questionnaires by the number originally distributed.. Let’s say your sample included 100 people and you sent questionnaires to each of those people. It would be wonderful if all 100 returned completed questionnaires, but the chances of that happening are about zero. If you’re lucky, perhaps 75 or so will return completed questionnaires. In this case, your response rate would be 75% (75 divided by 100). That’s pretty darn good. Though response rates vary, and researchers don’t always agree about what makes a good response rate, having three-quarters of your surveys returned would be considered good, even excellent, by most survey researchers. There has been lots of research done on how to improve a survey’s response rate. We covered some of these previously, but suggestions include personalizing questionnaires by, for example, addressing them to specific respondents rather than to some generic recipient such as “madam” or “sir”; enhancing the questionnaire’s credibility by providing details about the study, contact information for the researcher, and perhaps partnering with agencies likely to be respected by respondents such as universities, hospitals, or other relevant organizations; sending out prequestionnaire notices and postquestionnaire reminders; and including some token of appreciation with mailed questionnaires even if small, such as a $1 bill.

The major concern with response rates is that a low rate of response may introduce nonresponse biasThe possible result of having too few sample members return completed questionnaires; occurs when respondents differ in important ways from nonrespondents. into a study’s findings. What if only those who have strong opinions about your study topic return their questionnaires? If that is the case, we may well find that our findings don’t at all represent how things really are or, at the very least, we are limited in the claims we can make about patterns found in our data. While high return rates are certainly ideal, a recent body of research shows that concern over response rates may be overblown (Langer, 2003).Langer, G. (2003). About response rates: Some unresolved questions. Public Perspective, May/June, 16–18. Retrieved from http://www.aapor.org/Content/aapor/Resources/PollampSurveyFAQ1/DoResponseRatesMatter/Response_Rates_-_Langer.pdf Several studies have shown that low response rates did not make much difference in findings or in sample representativeness (Curtin, Presser, & Singer, 2000; Keeter, Kennedy, Dimock, Best, & Craighill, 2006; Merkle & Edelman, 2002).Curtin, R., Presser, S., & Singer, E. (2000). The effects of response rate changes on the index of consumer sentiment. Public Opinion Quarterly, 64, 413–428; Keeter, S., Kennedy, C., Dimock, M., Best, J., & Craighill, P. (2006). Gauging the impact of growing nonresponse on estimates from a national RDD telephone survey. Public Opinion Quarterly, 70, 759–779; Merkle, D. M., & Edelman, M. (2002). Nonresponse in exit polls: A comprehensive analysis. In M. Groves, D. A. Dillman, J. L. Eltinge, & R. J. A. Little (Eds.), Survey nonresponse (pp. 243–258). New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons. For now, the jury may still be out on what makes an ideal response rate and on whether, or to what extent, researchers should be concerned about response rates. Nevertheless, certainly no harm can come from aiming for as high a response rate as possible.

Whatever your survey’s response rate, the major concern of survey researchers once they have their nice, big stack of completed questionnaires is condensing their data into manageable, and analyzable, bits. One major advantage of quantitative methods such as survey research, as you may recall from Chapter 1 "Introduction", is that they enable researchers to describe large amounts of data because they can be represented by and condensed into numbers. In order to condense your completed surveys into analyzable numbers, you’ll first need to create a codebookA document that outlines how a survey researcher has translated her or his data from words into numbers.. A codebook is a document that outlines how a survey researcher has translated her or his data from words into numbers. An excerpt from the codebook I developed from my survey of older workers can be seen in Table 8.2 "Codebook Excerpt From Survey of Older Workers". The coded responses you see can be seen in their original survey format in Chapter 6 "Defining and Measuring Concepts", Figure 6.12 "Example of an Index Measuring Financial Security". As you’ll see in the table, in addition to converting response options into numerical values, a short variable name is given to each question. This shortened name comes in handy when entering data into a computer program for analysis.

Table 8.2 Codebook Excerpt From Survey of Older Workers

| Variable # | Variable name | Question | Options |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | FINSEC | In general, how financially secure would you say you are? | 1 = Not at all secure |

| 2 = Between not at all and moderately secure | |||

| 3 = Moderately secure | |||

| 4 = Between moderately and very secure | |||

| 5 = Very secure | |||

| 12 | FINFAM | Since age 62, have you ever received money from family members or friends to help make ends meet? | 0 = No |

| 1 = Yes | |||

| 13 | FINFAMT | If yes, how many times? | 1 = 1 or 2 times |

| 2 = 3 or 4 times | |||

| 3 = 5 times or more | |||

| 14 | FINCHUR | Since age 62, have you ever received money from a church or other organization to help make ends meet? | 0 = No |

| 1 = Yes | |||

| 15 | FINCHURT | If yes, how many times? | 1 = 1 or 2 times |

| 2 = 3 or 4 times | |||

| 3 = 5 times or more | |||

| 16 | FINGVCH | Since age 62, have you ever donated money to a church or other organization? | 0 = No |

| 1 = Yes | |||

| 17 | FINGVFAM | Since age 62, have you ever given money to a family member or friend to help them make ends meet? | 0 = No |

| 1 = Yes |

If you’ve administered your questionnaire the old fashioned way, via snail mail, the next task after creating your codebook is data entry. If you’ve utilized an online tool such as SurveyMonkey to administer your survey, here’s some good news—most online survey tools come with the capability of importing survey results directly into a data analysis program. Trust me—this is indeed most excellent news. (If you don’t believe me, I highly recommend administering hard copies of your questionnaire next time around. You’ll surely then appreciate the wonders of online survey administration.)

For those who will be conducting manual data entry, there probably isn’t much I can say about this task that will make you want to perform it other than pointing out the reward of having a database of your very own analyzable data. We won’t get into too many of the details of data entry, but I will mention a few programs that survey researchers may use to analyze data once it has been entered. The first is SPSS, or the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (http://www.spss.com). SPSS is a statistical analysis computer program designed to analyze just the sort of data quantitative survey researchers collect. It can perform everything from very basic descriptive statistical analysis to more complex inferential statistical analysis. SPSS is touted by many for being highly accessible and relatively easy to navigate (with practice). Other programs that are known for their accessibility include MicroCase (http://www.microcase.com/index.html), which includes many of the same features as SPSS, and Excel (http://office.microsoft.com/en-us/excel-help/about-statistical-analysis-tools-HP005203873.aspx), which is far less sophisticated in its statistical capabilities but is relatively easy to use and suits some researchers’ purposes just fine. Check out the web pages for each, which I’ve provided links to in the chapter’s endnotes, for more information about what each package can do.

Identifying Patterns

Data analysis is about identifying, describing, and explaining patterns. Univariate analysisAnalysis of a single variable. is the most basic form of analysis that quantitative researchers conduct. In this form, researchers describe patterns across just one variable. Univariate analysis includes frequency distributions and measures of central tendency. A frequency distribution is a way of summarizing the distribution of responses on a single survey question. Let’s look at the frequency distribution for just one variable from my older worker survey. We’ll analyze the item mentioned first in the codebook excerpt given earlier, on respondents’ self-reported financial security.

Table 8.3 Frequency Distribution of Older Workers’ Financial Security

| In general, how financially secure would you say you are? | Value | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Label | |||

| Not at all secure | 1 | 46 | 25.6 |

| Between not at all and moderately secure | 2 | 43 | 23.9 |

| Moderately secure | 3 | 76 | 42.2 |

| Between moderately and very secure | 4 | 11 | 6.1 |

| Very secure | 5 | 4 | 2.2 |

| Total valid cases = 180; no response = 3 | |||

As you can see in the frequency distribution on self-reported financial security, more respondents reported feeling “moderately secure” than any other response category. We also learn from this single frequency distribution that fewer than 10% of respondents reported being in one of the two most secure categories.

Another form of univariate analysis that survey researchers can conduct on single variables is measures of central tendency. Measures of central tendency tell us what the most common, or average, response is on a question. Measures of central tendency can be taken for any level variable of those we learned about in Chapter 6 "Defining and Measuring Concepts", from nominal to ratio. There are three kinds of measures of central tendency: modes, medians, and means. ModeA measure of central tendency that identifies the most common response given to a question. refers to the most common response given to a question. Modes are most appropriate for nominal-level variables. A medianA measure of central tendency that identifies the middle point in a distribution of responses. is the middle point in a distribution of responses. Median is the appropriate measure of central tendency for ordinal-level variables. Finally, the measure of central tendency used for interval- and ratio-level variables is the mean. To obtain a meanA measure of central tendency that identifies the average response to an interval- or ratio-level question; found by adding the value of all responses on a single variable and dividing by the total number of responses to that question., one must add the value of all responses on a given variable and then divide that number of the total number of responses.

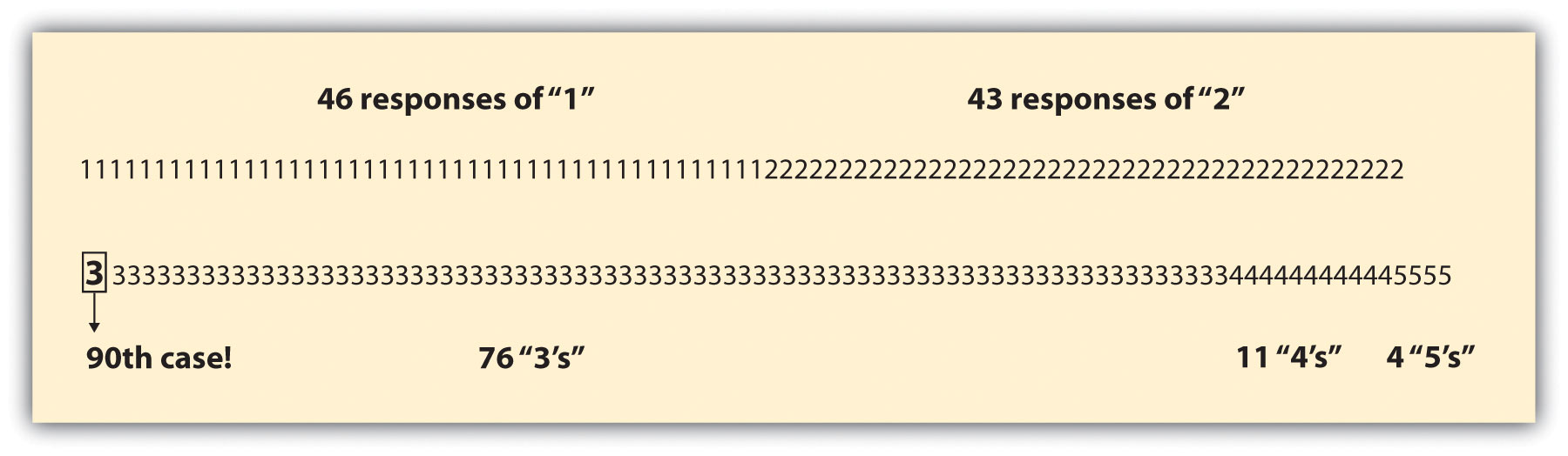

In the previous example of older workers’ self-reported levels of financial security, the appropriate measure of central tendency would be the median, as this is an ordinal-level variable. If we were to list all responses to the financial security question in order and then choose the middle point in that list, we’d have our median. In Figure 8.12 "Distribution of Responses and Median Value on Workers’ Financial Security", the value of each response to the financial security question is noted, and the middle point within that range of responses is highlighted. To find the middle point, we simply divide the number of valid cases by two. The number of valid cases, 180, divided by 2 is 90, so we’re looking for the 90th value on our distribution to discover the median. As you’ll see in Figure 8.12 "Distribution of Responses and Median Value on Workers’ Financial Security", that value is 3, thus the median on our financial security question is 3, or “moderately secure.”

Figure 8.12 Distribution of Responses and Median Value on Workers’ Financial Security

As you can see, we can learn a lot about our respondents simply by conducting univariate analysis of measures on our survey. We can learn even more, of course, when we begin to examine relationships among variables. Either we can analyze the relationships between two variables, called bivariate analysisAnalysis of the relationships between two variables., or we can examine relationships among more than two variables. This latter type of analysis is known as multivariate analysisAnalysis of the relationships among multiple variables..

Bivariate analysis allows us to assess covariationOccurs when changes in one variable happen together with changes in another. among two variables. This means we can find out whether changes in one variable occur together with changes in another. If two variables do not covary, they are said to have independenceOccurs when there is no relationship between the variables in question.. This means simply that there is no relationship between the two variables in question. To learn whether a relationship exists between two variables, a researcher may cross-tabulateThe process for creating a contingency table. the two variables and present their relationship in a contingency table. A contingency tableDisplays how variation on one variable may be contingent on variation on another. shows how variation on one variable may be contingent on variation on the other. Let’s take a look at a contingency table. In Table 8.4 "Financial Security Among Men and Women Workers Age 62 and Up", I have cross-tabulated two questions from my older worker survey: respondents’ reported gender and their self-rated financial security.

Table 8.4 Financial Security Among Men and Women Workers Age 62 and Up

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| Not financially secure (%) | 44.1 | 51.8 |

| Moderately financially secure (%) | 48.9 | 39.2 |

| Financially secure (%) | 7.0 | 9.0 |

| Total | N = 43 | N = 135 |

You’ll see in Table 8.4 "Financial Security Among Men and Women Workers Age 62 and Up" that I collapsed a couple of the financial security response categories (recall that there were five categories presented in Table 8.3 "Frequency Distribution of Older Workers’ Financial Security"; here there are just three). Researchers sometimes collapse response categories on items such as this in order to make it easier to read results in a table. You’ll also see that I placed the variable “gender” in the table’s columns and “financial security” in its rows. Typically, values that are contingent on other values are placed in rows (a.k.a. dependent variables), while independent variables are placed in columns. This makes comparing across categories of our independent variable pretty simple. Reading across the top row of our table, we can see that around 44% of men in the sample reported that they are not financially secure while almost 52% of women reported the same. In other words, more women than men reported that they are not financially secure. You’ll also see in the table that I reported the total number of respondents for each category of the independent variable in the table’s bottom row. This is also standard practice in a bivariate table, as is including a table heading describing what is presented in the table.

Researchers interested in simultaneously analyzing relationships among more than two variables conduct multivariate analysis. If I hypothesized that financial security declines for women as they age but increases for men as they age, I might consider adding age to the preceding analysis. To do so would require multivariate, rather than bivariate, analysis. We won’t go into detail here about how to conduct multivariate analysis of quantitative survey items here, but we will return to multivariate analysis in Chapter 14 "Reading and Understanding Social Research", where we’ll discuss strategies for reading and understanding tables that present multivariate statistics. If you are interested in learning more about the analysis of quantitative survey data, I recommend checking out your campus’s offerings in statistics classes. The quantitative data analysis skills you will gain in a statistics class could serve you quite well should you find yourself seeking employment one day.

Key Takeaways

- While survey researchers should always aim to obtain the highest response rate possible, some recent research argues that high return rates on surveys may be less important than we once thought.

- There are several computer programs designed to assist survey researchers with analyzing their data include SPSS, MicroCase, and Excel.

- Data analysis is about identifying, describing, and explaining patterns.

- Contingency tables show how, or whether, one variable covaries with another.

Exercises

- Codebooks can range from relatively simple to quite complex. For an excellent example of a more complex codebook, check out the coding for the General Social Survey (GSS): http://publicdata.norc.org:41000/gss/documents//BOOK/GSS_Codebook.pdf.

- The GSS allows researchers to cross-tabulate GSS variables directly from its website. Interested? Check out http://www.norc.uchicago.edu/GSS+Website/Data+Analysis.