This is “Tropical Cyclones (Hurricanes)”, section 5.5 from the book Regional Geography of the World: Globalization, People, and Places (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

5.5 Tropical Cyclones (Hurricanes)

Learning Objectives

- Describe how and why hurricanes form.

- Outline why hurricanes have the potential to be so dangerous.

- Explain why hurricanes mainly occur in the tropics.

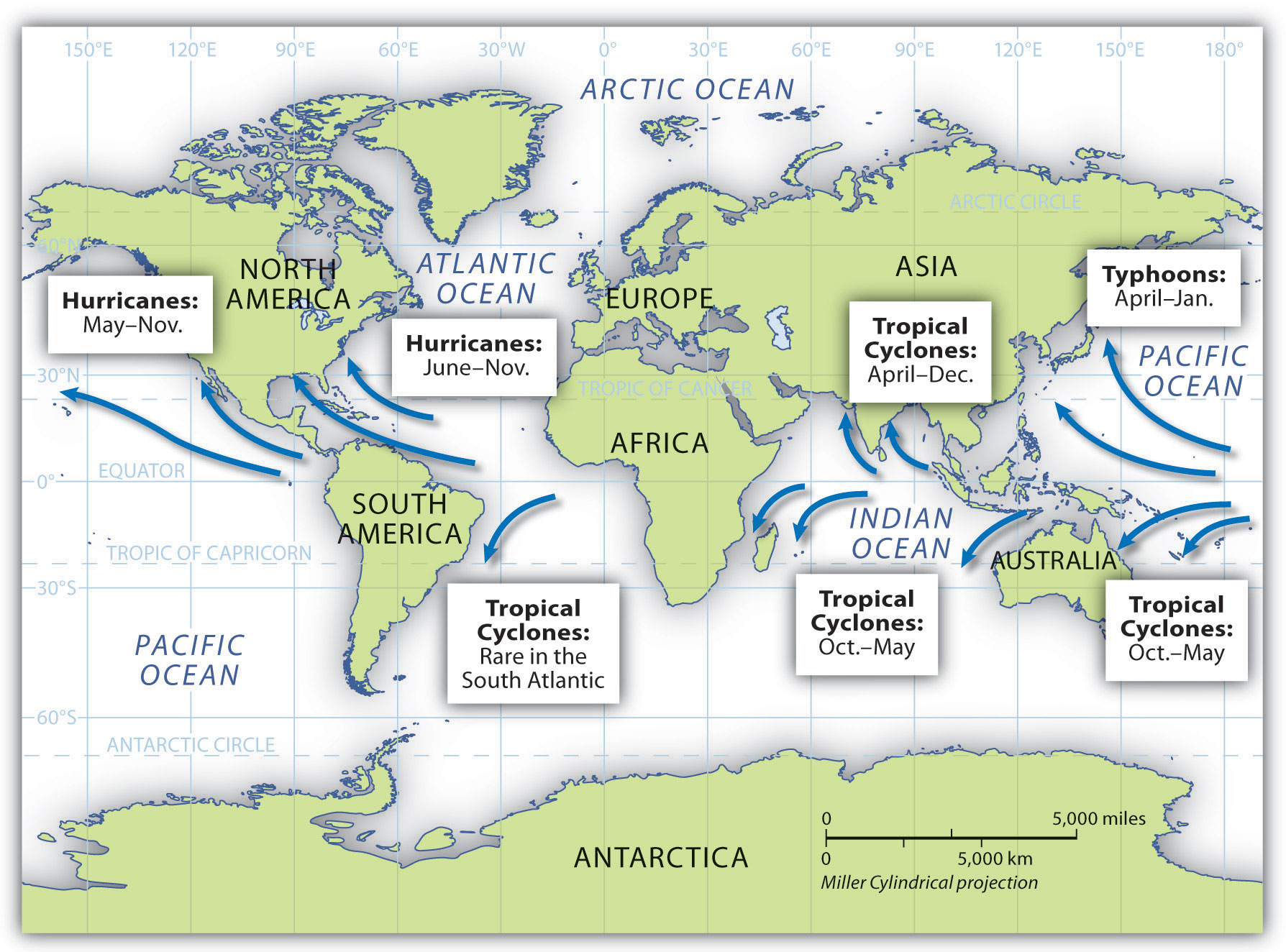

Above the oceans just north and south of the equator, a weather phenomenon called a tropical cyclone can develop that can drastically alter the physical and cultural landscape if it reaches land. In the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, this weather pattern is called a hurricaneTropical cyclone that occurs in the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea.. In the North Pacific Ocean, the same type of weather pattern is called a typhoonTropical cyclone that occurs in the North Pacific Ocean.. In the Indian Ocean region and in the South Pacific Ocean, it is called a tropical cyclone or just a cycloneTropical cyclone that occurs in the Indian Ocean region and in the South Pacific Ocean.. All these storms are considered tropical because they almost always develop between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn.

Figure 5.35 Cyclones, Hurricanes, and Typhoons and Their Respective Locations around the World

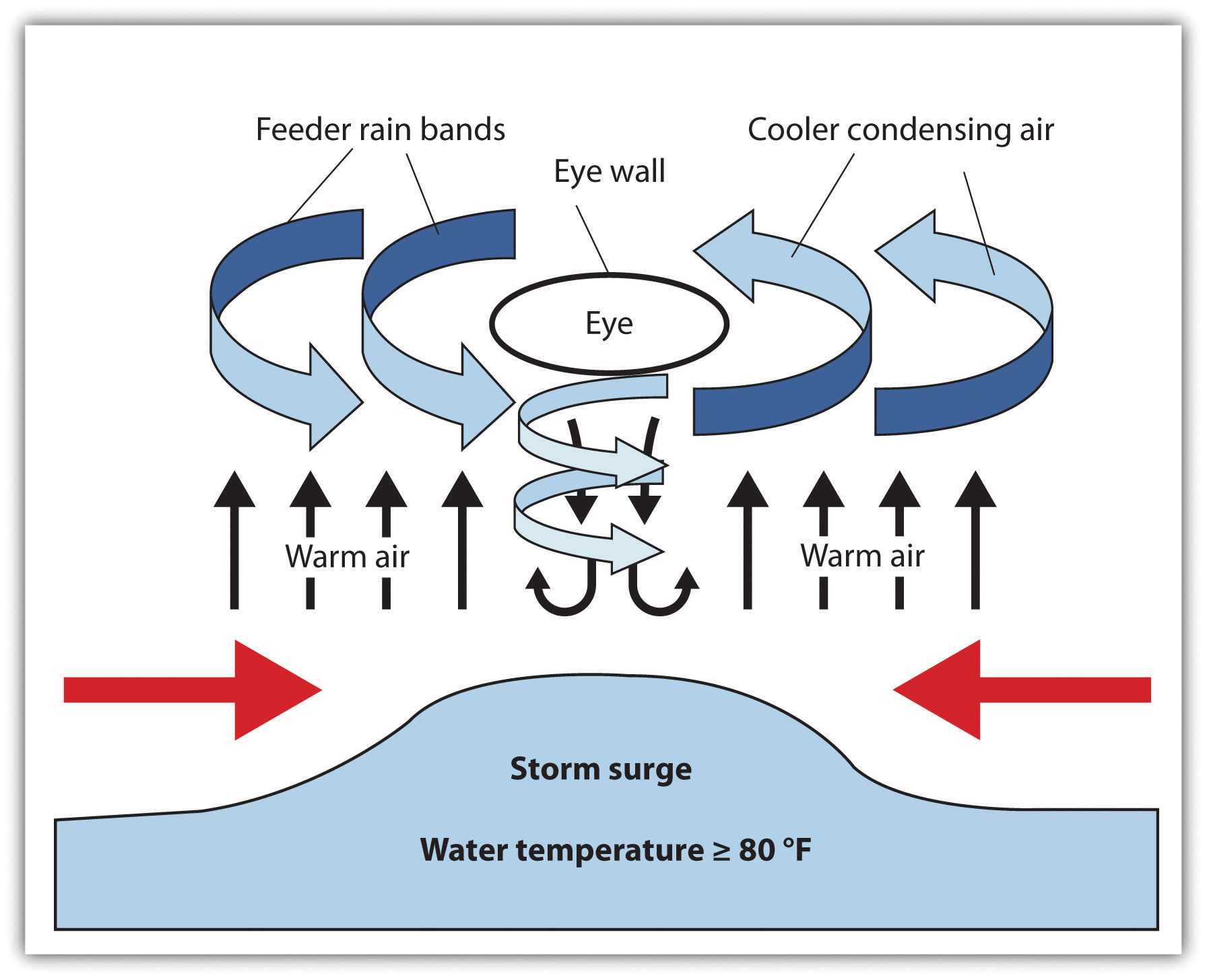

Hurricanes develop over water that is warmer than 80 ºF. As the air heats, it rises rapidly, drawing incoming air to replace the rising air and creating strong wind currents and storm conditions. The rapidly rising humid air then cools and condenses, resulting in heavy rains and a downdraft of cooler air. The rotation of the earth causes the storm to rotate in a cyclonic pattern. North of the equator, tropical storms rotate in a counterclockwise direction. South of the equator, tropical storms rotate in a clockwise direction.

Hurricanes start out as tropical depressions: storms with wind speeds between twenty-five and thirty-eight miles per hour. Cyclonic motion and warm temperatures feed the system. If a storm reaches sustained winds of thirty-nine to seventy-three miles per hour, it is upgraded to a tropical storm. Tropical depressions are numbered; tropical storms are named. When winds reach a sustained speed of seventy-four miles per hour, a storm is classified as a hurricane.

Hurricane Dynamics

Hot air rises. A water temperature of at least 80 ºF can sustain rising air in the development of a tropical depression. These storms continue to be driven by the release of the latent heat of condensation, which occurs when moist air is carried upward and its water vapor condenses. This heat is distributed within the storm to energize it. As the system gains strength, a full-scale hurricane can develop. Rising warm air creates a low-pressure area that draws in air from the surface. This action pushes water toward the center, creating what is called a storm surgeWhen water is pushed toward the hurricane’s center, it causes flooding when hitting landfall; usually the feature of a hurricane that produces the most damage or loss of life.. Storm surges can average five to twenty feet or more depending on the category of the hurricane. Cyclonic rotation is created by rotation of the earth in a process called the Coriolis effect. The Coriolis effect is less prominent along the equator, so tropical cyclones usually do not develop within five degrees north or south of the equator.

When a hurricane makes landfall (comes ashore), the storm surge causes extensive flooding. More people are killed by flooding because of the storm surge than by any other hurricane effect. At the center of the cyclonic system is the hurricane’s eye, where there is a downdraft of sinking air but the wind is calm and there are no clouds. The eye can extend from one to one hundred miles or more. Many people who have been in the eye of the hurricane believe the storm has passed, but in reality they are in the center of it.

Bordering the eye of a storm is the eye wall, where the strongest winds and heaviest rainfall are found. This is the most violent part of the hurricane. Beyond the eye wall are feeder bands, with thunderstorms and rain showers that spiral inward toward the eye wall. Feeder bands can extend out for many miles and increase as the heat engine feeds the storm. Hurricanes lose their energy when they move over land because of the lack of heat generation. Once on land, the storm system breaks down. Rainfall and winds can continue, but with decreased intensity.

Figure 5.36 Dynamics of Hurricane Components

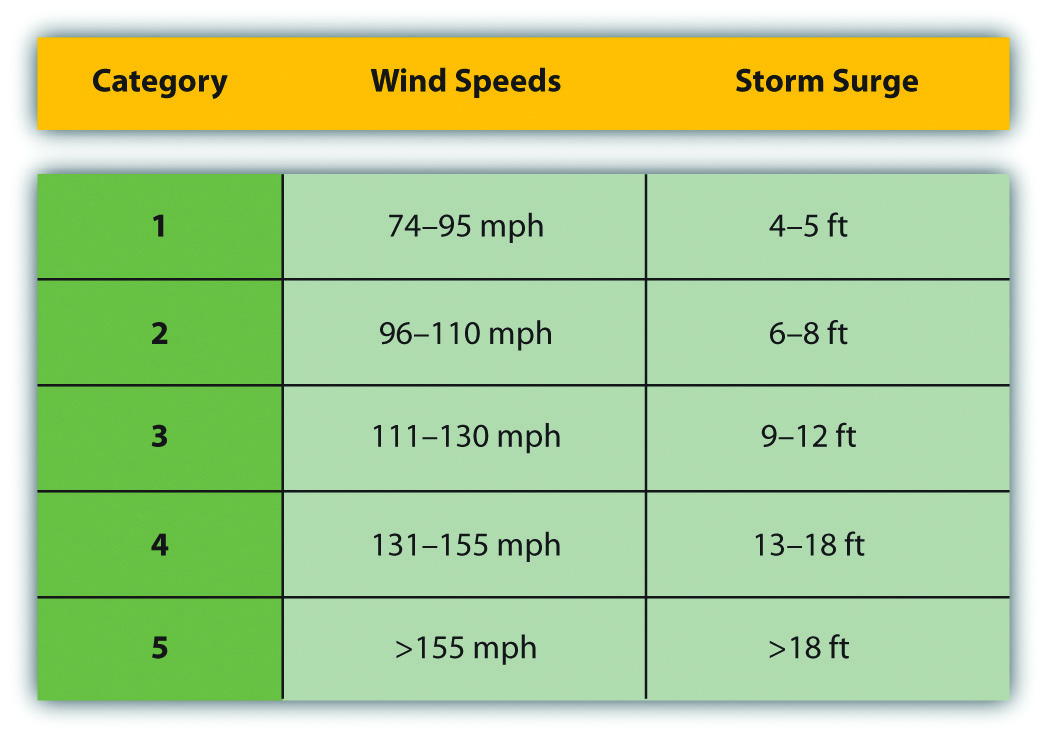

Centuries ago, the Spanish used the term hurakan, an indigenous word for “evil spirits” or “devil wind,” to name the storms that sank their ships in the Caribbean. Hurricanes are rated according to sustained wind speed using the Saffir-Simpson Scale. This scale rates a hurricane according to five categories (see Figure 5.37 "Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale"). Category 1 hurricanes have sustained wind speeds of at least seventy-four miles per hour and can inflict heavy damage to buildings, roofs, windows, and the environment. Category 5 hurricanes have sustained winds of more than 155 miles per hour and destroy everything in their paths. Hurricanes can also spawn tornadoes, which increase their potential for destruction.

Figure 5.37 Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale

Annually, more than one hundred tropical disturbances develop in the North Atlantic, but only about ten make it to a tropical storm status and five to six become hurricanes. Only two or three hit the United States in a typical year. Hurricane season for the North Atlantic lasts from June 1 to November 30. Tropical cyclones develop during the warmest season of the year when the water temperature is the highest. Though these weather patterns can bring enormous devastation to the landscape, they also redistribute moisture in the form of rain and help regulate global temperatures.

The devastating nature of tropical cyclones is the main concern when forecasting a potential storm. In 1970, the Bholo cyclone hit the coast of Bangladesh, resulting in the death of between three hundred thousand and one million people. A number of cyclones that killed more than one hundred thousand people each have hit Bangladesh in the past century. Typhoon Tip in the Northwest Pacific in 1979 is the largest tropical cyclone on record, with wind speeds of more than 190 miles per hour and a total diameter of more than 1,350 miles—equal to the distance from the Mexican border to the Canadian border in the United States. Typhoons can be, on average, twice the size of hurricanes.

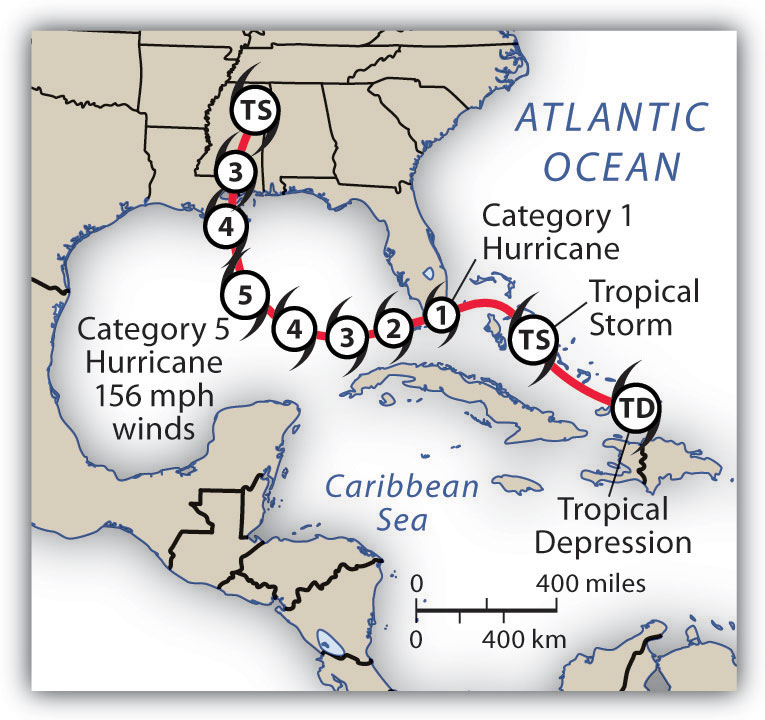

Figure 5.38 Hurricane Katrina at Various Stages of Its Development across the Gulf of Mexico

Hurricane Camille was the strongest US hurricane on record at landfall, with sustained winds of 190 miles per hour and wind gusts of up to 210 miles per hour. Camille hit the US Mississippi coast in 1969 as a category 5 hurricane. It devastated everything in its path, killing 259 people. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 was one of the most costly storms to impact the United States. Katrina started out as a tropical depression while in the Bahamas. The storm reached a category 5 hurricane as it passed through the Gulf of Mexico but diminished in strength when making landfall in Louisiana, with sustained winds of 125 miles per hour (a strong category 3 hurricane). Katrina caused widespread devastation along the central Gulf Coast and devastated the city of New Orleans. At least 1,836 people lost their lives, and the cleanup cost an estimated $100 billion.

Since records were started in 1851 for hurricanes in the Atlantic Basin, there have been thirty-two hurricanes that reached category 5 in the region. A few of them have reached all the way to the Central American coast. Hurricane Mitch hit the coast of Central America in 1998 and dumped over seventy-five inches of rain across the countries of Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala. Devastating winds and heavy rain caused the deaths of up to twenty thousand people. Destructive category 5 hurricanes Edith and Felix made landfall in Nicaragua in 1971 and 2007, respectively. The Yucatán Peninsula and the coast of Mexico have also witnessed a number of devastating category 5 hurricanes.

The Caribbean Basin is located in the path of many hurricanes developing out of the Cape Verde region of the North Atlantic. For example, 2008 was a particularly devastating hurricane season, with sixteen tropical storms and eight full-scale hurricanes, five of which caused massive devastation. Three category 4 hurricanes (Ike, Gustav, and Paloma) cut through the northern Caribbean to hit the Greater Antilles. The most devastating was Ike, which ripped through the Caribbean, across the entire length of Cuba, and then on to the Gulf Coast of Louisiana and Texas. Ike’s immense size contributed to the fact that it was the third most costly hurricane on record. Ike caused an estimated $7.3 billion in damage to Cuba and more than $29 billion in damage in the United States. Hurricane Gustav made landfall in Hispaniola and Jamaica before increasing in strength and causing about $3.1 billion in damage to Cuba. In November of 2008, Hurricane Paloma made landfall in Cuba and caused an additional $300 million in damage to the island. Many of the other Caribbean islands were also devastated by the hurricanes that hit the region in 2008.

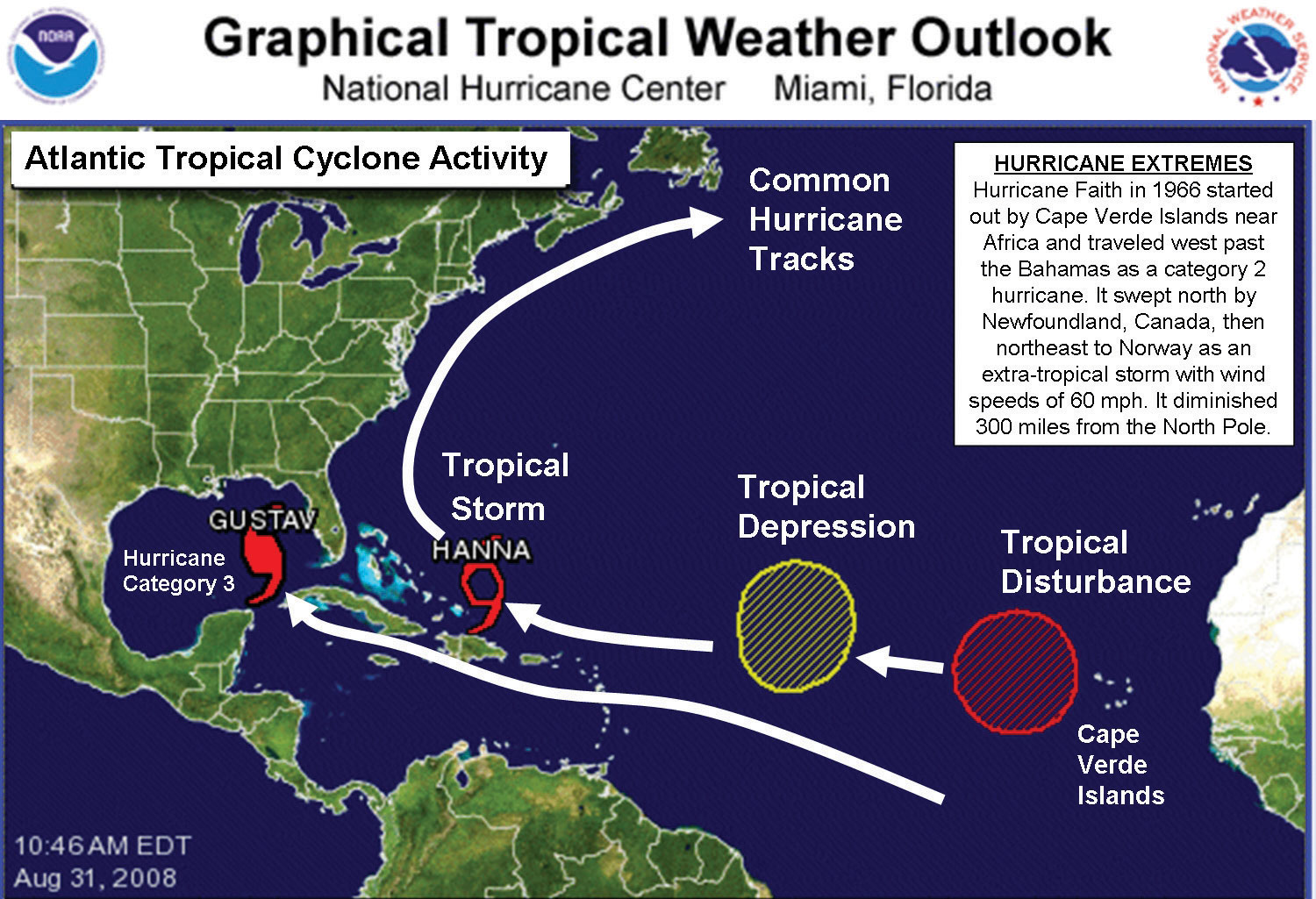

Figure 5.39 Direct Path of Hurricane Activity

This photo indicates hurricane Gustav and tropical storm Hanna, as well as an existing tropical depression (which became Hurricane Ike) and a tropical disturbance. Tropical Storm Hanna later developed into a full-scale hurricane.

Source: Map courtesy of National Hurricane Center, http://www.nhc.noaa.gov.

Key Takeaways

- Tropical cyclones occur in the tropical regions over warm ocean water. In the North Atlantic, they are called hurricanes; in the North Pacific, they are called typhoons; and in the Indian Ocean, they are called cyclones.

- Hurricanes start as tropical depressions with wind speeds of at least twenty-five miles per hour. As wind speeds increase to thirty-nine miles per hour, the disturbances are called tropical storms and are named. When wind speeds reach seventy-four miles per hour, they become hurricanes.

- Rising air pulls water to the center of the storm, creating a storm surge, the most dangerous feature of the storm because of the immense flooding it can cause when reaching land.

- Hurricane season is between June 1 and November 30. Cruise ships do not usually operate in the Caribbean during this time.

Discussion and Study Questions

- Why do tropical cyclones form near the equator?

- What are the stages of weather patterns that build up to a tropical cyclone (hurricane)?

- What are the main components of a hurricane?

- What part of the hurricane usually causes the most damage or loss of life?

- How are hurricanes classified? What are the main categories of a hurricane?

- How many tropical disturbances develop in the North Atlantic each year? How many develop into full-scale hurricanes each year? How many hurricanes usually hit the United States each year?

- Why is it often more difficult for the Caribbean islands to recover from a hurricane than the United States?

- What path do hurricanes usually follow in the North Atlantic?

- Where do cyclones and typhoons develop other than the North Atlantic?

- When is the main hurricane season in the North Atlantic? How does the hurricane season impact tourism in the Caribbean?