This is “Why Public Speaking Matters Today”, chapter 1 from the book Public Speaking: Practice and Ethics (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

Chapter 1 Why Public Speaking Matters Today

Public Speaking in the Twenty-First Century

© Thinkstock

Public speaking is the process of designing and delivering a messageAny verbal or nonverbal stimulus that is meaningful to a receiver. to an audience. Effective public speaking involves understanding your audience and speaking goals, choosing elements for the speech that will engage your audience with your topic, and delivering your message skillfully. Good public speakers understand that they must plan, organize, and revise their material in order to develop an effective speech. This book will help you understand the basics of effective public speaking and guide you through the process of creating your own presentations. We’ll begin by discussing the ways in which public speaking is relevant to you and can benefit you in your career, education, and personal life.

In a world where people are bombarded with messages through television, social media, and the Internet, one of the first questions you may ask is, “Do people still give speeches?” Well, type the words “public speaking” into Amazon.com or Barnesandnoble.com, and you will find more than two thousand books with the words “public speaking” in the title. Most of these and other books related to public speaking are not college textbooks. In fact, many books written about public speaking are intended for very specific audiences: A Handbook of Public Speaking for Scientists and Engineers (by Peter Kenny), Excuse Me! Let Me Speak!: A Young Person’s Guide to Public Speaking (by Michelle J. Dyett-Welcome), Professionally Speaking: Public Speaking for Health Professionals (by Frank De Piano and Arnold Melnick), and Speaking Effectively: A Guide for Air Force Speakers (by John A. Kline). Although these different books address specific issues related to nurses, engineers, or air force officers, the content is basically the same. If you search for “public speaking” in an online academic database, you’ll find numerous articles on public speaking in business magazines (e.g., BusinessWeek, Nonprofit World) and academic journals (e.g., Harvard Business Review, Journal of Business Communication). There is so much information available about public speaking because it continues to be relevant even with the growth of technological means of communication. As author and speaker Scott Berkun writes in his blog, “For all our tech, we’re still very fond of the most low tech thing there is: a monologue.”Berkun, S. (2009, March 4). Does public speaking matter in 2009? [Web log message]. Retrieved from http://www.scottberkun.com/blog People continue to spend millions of dollars every year to listen to professional speakers. For example, attendees of the 2010 TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design) conference, which invites speakers from around the world to share their ideas in short, eighteen-minute presentations, paid six thousand dollars per person to listen to fifty speeches over a four-day period.

Technology can also help public speakers reach audiences that were not possible to reach in the past. Millions of people heard about and then watched Randy Pausch’s “Last Lecture” online. In this captivating speech, Randy Pausch, a Carnegie Mellon University professor who retired at age forty-six after developing inoperable tumors, delivered his last lecture to the students, faculty, and staff. This inspiring speech was turned into a DVD and a best-selling book that was eventually published in more than thirty-five languages.Carnegie Mellon University. (n.d.). Randy Pausch’s last lecture. Retrieved June 6, 2011, from http://www.cmu.edu/randyslecture

We realize that you may not be invited to TED to give the speech of your life or create a speech so inspirational that it touches the lives of millions via YouTube; however, all of us will find ourselves in situations where we will be asked to give a speech, make a presentation, or just deliver a few words. In this chapter, we will first address why public speaking is important, and then we will discuss models that illustrate the process of public speaking itself.

1.1 Why Is Public Speaking Important?

Learning Objectives

- Explore three types of public speaking in everyday life: informative, persuasive, and entertaining.

- Understand the benefits of taking a course in public speaking.

- Explain the benefits people get from engaging in public speaking.

© Thinkstock

In today’s world, we are constantly bombarded with messages both good and bad. No matter where you live, where you work or go to school, or what kinds of media you use, you are probably exposed to hundreds. if not thousands, of advertising messages every day. Researcher Norman W. Edmund estimates that by 2020 the amount of knowledge in the world will double every seventy-three days.Edmund, N. W. (2005). End the biggest educational and intellectual blunder in history: A $100,000 challenge to our top educational leaders. Ft. Lauderdale, FL: Scientific Method Publishing Co. Because we live in a world where we are overwhelmed with content, communicating information in a way that is accessible to others is more important today than ever before. To help us further understand why public speaking is important, we will first examine public speaking in everyday life. We will then discuss how public speaking can benefit you personally.

Everyday Public Speaking

Every single day people across the United States and around the world stand up in front of some kind of audience and speak. In fact, there’s even a monthly publication that reproduces some of the top speeches from around the United States called Vital Speeches of the Day (http://www.vsotd.com). Although public speeches are of various types, they can generally be grouped into three categories based on their intended purpose: informative, persuasive, and entertaining.

Informative Speaking

One of the most common types of public speaking is informative speakingSpeaking with the purpose of sharing knowledge or information with an audience.. The primary purpose of informative presentations is to share one’s knowledge of a subject with an audience. Reasons for making an informative speech vary widely. For example, you might be asked to instruct a group of coworkers on how to use new computer software or to report to a group of managers how your latest project is coming along. A local community group might wish to hear about your volunteer activities in New Orleans during spring break, or your classmates may want you to share your expertise on Mediterranean cooking. What all these examples have in common is the goal of imparting information to an audience.

Informative speaking is integrated into many different occupations. Physicians often lecture about their areas of expertise to medical students, other physicians, and patients. Teachers find themselves presenting to parents as well as to their students. Firefighters give demonstrations about how to effectively control a fire in the house. Informative speaking is a common part of numerous jobs and other everyday activities. As a result, learning how to speak effectively has become an essential skill in today’s world.

Persuasive Speaking

A second common reason for speaking to an audience is to persuadeThe intentional attempt to get another person or persons to change or reinforce specific beliefs, values, and/or behaviors. others. In our everyday lives, we are often called on to convince, motivate, or otherwise persuade others to change their beliefs, take an action, or reconsider a decision. Advocating for music education in your local school district, convincing clients to purchase your company’s products, or inspiring high school students to attend college all involve influencing other people through public speaking.

For some people, such as elected officials, giving persuasive speeches is a crucial part of attaining and continuing career success. Other people make careers out of speaking to groups of people who pay to listen to them. Motivational authors and speakers, such as Les Brown (http://www.lesbrown.com), make millions of dollars each year from people who want to be motivated to do better in their lives. Brian Tracy, another professional speaker and author, specializes in helping business leaders become more productive and effective in the workplace (http://www.briantracy.com).

Whether public speaking is something you do every day or just a few times a year, persuading others is a challenging task. If you develop the skill to persuade effectively, it can be personally and professionally rewarding.

Entertaining Speaking

Entertaining speakingSpeech designed to captivate an audience’s attention and regale or amuse them while delivering a clear message. involves an array of speaking occasions ranging from introductions to wedding toasts, to presenting and accepting awards, to delivering eulogies at funerals and memorial services in addition to after-dinner speeches and motivational speeches. Entertaining speaking has been important since the time of the ancient Greeks, when Aristotle identified epideictic speaking (speaking in a ceremonial context) as an important type of address. As with persuasive and informative speaking, there are professionals, from religious leaders to comedians, who make a living simply from delivering entertaining speeches. As anyone who has watched an awards show on television or has seen an incoherent best man deliver a wedding toast can attest, speaking to entertain is a task that requires preparation and practice to be effective.

Personal Benefits of Public Speaking

Oral communication skills were the number one skill that college graduates found useful in the business world, according to a study by sociologist Andrew Zekeri.Zekeri, A. A. (2004). College curriculum competencies and skills former students found essential to their careers. College Student Journal, 38, 412–422. That fact alone makes learning about public speaking worthwhile. However, there are many other benefits of communicating effectively for the hundreds of thousands of college students every year who take public speaking courses. Let’s take a look at some of the personal benefits you’ll get both from a course in public speaking and from giving public speeches.

Benefits of Public Speaking Courses

In addition to learning the process of creating and delivering an effective speech, students of public speaking leave the class with a number of other benefits as well. Some of these benefits include

- developing critical thinking skills,

- fine-tuning verbal and nonverbal skills,

- overcoming fear of public speaking.

Developing Critical Thinking Skills

One of the very first benefits you will gain from your public speaking course is an increased ability to think critically. Problem solving is one of many critical thinking skills you will engage in during this course. For example, when preparing a persuasive speech, you’ll have to think through real problems affecting your campus, community, or the world and provide possible solutions to those problems. You’ll also have to think about the positive and negative consequences of your solutions and then communicate your ideas to others. At first, it may seem easy to come up with solutions for a campus problem such as a shortage of parking spaces: just build more spaces. But after thinking and researching further you may find out that building costs, environmental impact from loss of green space, maintenance needs, or limited locations for additional spaces make this solution impractical. Being able to think through problems and analyze the potential costs and benefits of solutions is an essential part of critical thinking and of public speaking aimed at persuading others. These skills will help you not only in public speaking contexts but throughout your life as well. As we stated earlier, college graduates in Zekeri’s study rated oral communication skills as the most useful for success in the business world. The second most valuable skill they reported was problem-solving ability, so your public speaking course is doubly valuable!

Another benefit to public speaking is that it will enhance your ability to conduct and analyze research. Public speakers must provide credible evidence within their speeches if they are going to persuade various audiences. So your public speaking course will further refine your ability to find and utilize a range of sources.

Fine-Tuning Verbal and Nonverbal Skills

A second benefit of taking a public speaking course is that it will help you fine-tune your verbal and nonverbal communication skills. Whether you competed in public speaking in high school or this is your first time speaking in front of an audience, having the opportunity to actively practice communication skills and receive professional feedback will help you become a better overall communicator. Often, people don’t even realize that they twirl their hair or repeatedly mispronounce words while speaking in public settings until they receive feedback from a teacher during a public speaking course. People around the United States will often pay speech coaches over one hundred dollars per hour to help them enhance their speaking skills. You have a built-in speech coach right in your classroom, so it is to your advantage to use the opportunity to improve your verbal and nonverbal communication skills.

Overcoming Fear of Public Speaking

An additional benefit of taking a public speaking class is that it will help reduce your fear of public speaking. Whether they’ve spoken in public a lot or are just getting started, most people experience some anxiety when engaging in public speaking. Heidi Rose and Andrew Rancer evaluated students’ levels of public speaking anxiety during both the first and last weeks of their public speaking class and found that those levels decreased over the course of the semester.Rose, H. M., & Rancer, A. S. (1993). The impact of basic courses in oral interpretation and public speaking on communication apprehension. Communication Reports, 6, 54–60. One explanation is that people often have little exposure to public speaking. By taking a course in public speaking, students become better acquainted with the public speaking process, making them more confident and less apprehensive. In addition, you will learn specific strategies for overcoming the challenges of speech anxiety. We will discuss this topic in greater detail in Chapter 3 "Speaking Confidently".

Benefits of Engaging in Public Speaking

Once you’ve learned the basic skills associated with public speaking, you’ll find that being able to effectively speak in public has profound benefits, including

- influencing the world around you,

- developing leadership skills,

- becoming a thought leader.

Influencing the World around You

If you don’t like something about your local government, then speak out about your issue! One of the best ways to get our society to change is through the power of speech. Common citizens in the United States and around the world, like you, are influencing the world in real ways through the power of speech. Just type the words “citizens speak out” in a search engine and you’ll find numerous examples of how common citizens use the power of speech to make real changes in the world—for example, by speaking out against “fracking” for natural gas (a process in which chemicals are injected into rocks in an attempt to open them up for fast flow of natural gas or oil) or in favor of retaining a popular local sheriff. One of the amazing parts of being a citizen in a democracy is the right to stand up and speak out, which is a luxury many people in the world do not have. So if you don’t like something, be the force of change you’re looking for through the power of speech.

Developing Leadership Skills

Have you ever thought about climbing the corporate ladder and eventually finding yourself in a management or other leadership position? If so, then public speaking skills are very important. Hackman and Johnson assert that effective public speaking skills are a necessity for all leaders.Hackman, M. Z., & Johnson, C. E. (2004). Leadership: A communication perspective (4th ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland. If you want people to follow you, you have to communicate effectively and clearly what followers should do. According to Bender, “Powerful leadership comes from knowing what matters to you. Powerful presentations come from expressing this effectively. It’s important to develop both.”Bender, P. U. (1998). Stand, deliver and lead. Ivey Business Journal, 62(3), 46–47. One of the most important skills for leaders to develop is their public speaking skills, which is why executives spend millions of dollars every year going to public speaking workshops; hiring public speaking coaches; and buying public speaking books, CDs, and DVDs.

Becoming a Thought Leader

Even if you are not in an official leadership position, effective public speaking can help you become a “thought leaderAn individual who contributes new ideas that help various aspects of society..” Joel Kurtzman, editor of Strategy & Business, coined this term to call attention to individuals who contribute new ideas to the world of business. According to business consultant Ken Lizotte, “when your colleagues, prospects, and customers view you as one very smart guy or gal to know, then you’re a thought leader.”Lizotte, K. (2008). The expert’s edge: Become the go-to authority people turn to every time [Kindle 2 version]. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Retrieved from Amazon.com (locations 72–78) Typically, thought leaders engage in a range of behaviors, including enacting and conducting research on business practices. To achieve thought leader status, individuals must communicate their ideas to others through both writing and public speaking. Lizotte demonstrates how becoming a thought leader can be personally and financially rewarding at the same time: when others look to you as a thought leader, you will be more desired and make more money as a result. Business gurus often refer to “intellectual capital,” or the combination of your knowledge and ability to communicate that knowledge to others.Lizotte, K. (2008). The expert’s edge: Become the go-to authority people turn to every time [Kindle 2 version]. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Retrieved from Amazon.com Whether standing before a group of executives discussing the next great trend in business or delivering a webinar (a seminar over the web), thought leaders use public speaking every day to create the future that the rest of us live in.

Key Takeaways

- People have many reasons for engaging in public speaking, but the skills necessary for public speaking are applicable whether someone is speaking for informative, persuasive, or entertainment reasons.

- Taking a public speaking class will improve your speaking skills, help you be a more critical thinker, fine-tune your verbal and nonverbal communication skills, and help you overcome public speaking anxiety.

- Effective public speaking skills have many direct benefits for the individual speaker, including influencing the world around you, developing leadership skills, and becoming a go-to person for ideas and solutions.

Exercises

- Talk to people who are currently working in the career you hope to pursue. Of the three types of public speaking discussed in the text, which do they use most commonly use in their work?

- Read one of the free speeches available at http://www.vsotd.com. What do you think the speaker was trying to accomplish? What was her or his reason for speaking?

- Which personal benefit are you most interested in receiving from a public speaking class? Why?

1.2 The Process of Public Speaking

Learning Objectives

- Identify the three components of getting your message across to others.

- Distinguish between the interactional models of communication and the transactional model of communication.

- Explain the three principles discussed in the dialogical theory of public speaking.

© Thinkstock

As noted earlier, all of us encounter thousands of messages in our everyday environments, so getting your idea heard above all the other ones is a constant battle. Some speakers will try gimmicks, but we strongly believe that getting your message heard depends on three fundamental components: message, skill, and passion. The first part of getting your message across is the message itself. When what you are saying is clear and coherent, people are more likely to pay attention to it. On the other hand, when a message is ambiguous, people will often stop paying attention. Our discussions in the first part of this book involve how to have clear and coherent content.

The second part of getting your message heard is having effective communication skills. You may have the best ideas in the world, but if you do not possess basic public speaking skills, you’re going to have a problem getting anyone to listen. In this book, we will address the skills you must possess to effectively communicate your ideas to others.

Lastly, if you want your message to be heard, you must communicate passion for your message. One mistake that novice public speakers make is picking topics in which they have no emotional investment. If an audience can tell that you don’t really care about your topic, they will just tune you out. Passion is the extra spark that draws people’s attention and makes them want to listen to your message.

In this section, we’re going to examine the process of public speaking by first introducing you to a basic model of public speaking and then discussing how public speaking functions as dialogue. These models will give you a basic understanding of the communication process and some challenges that you may face as a speaker.

Models of Public Speaking

A basic model of human communication is one of the first topics that most communication teachers start with in any class. For our focus on public speaking, we will introduce two widely discussed models in communication: interactional and transactional.

Interactional Model of Public Speaking

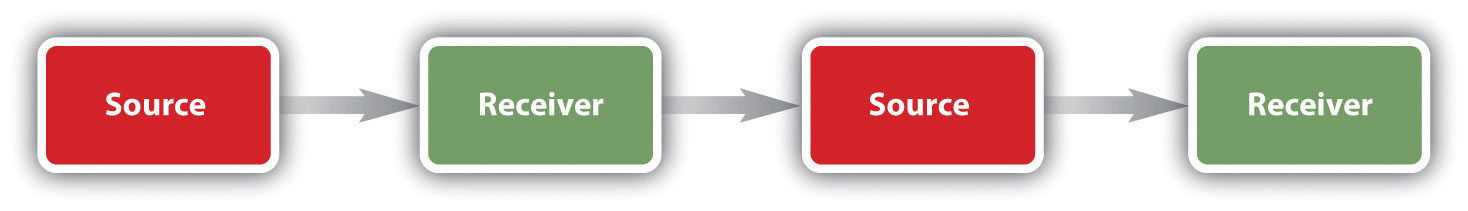

Linear Model

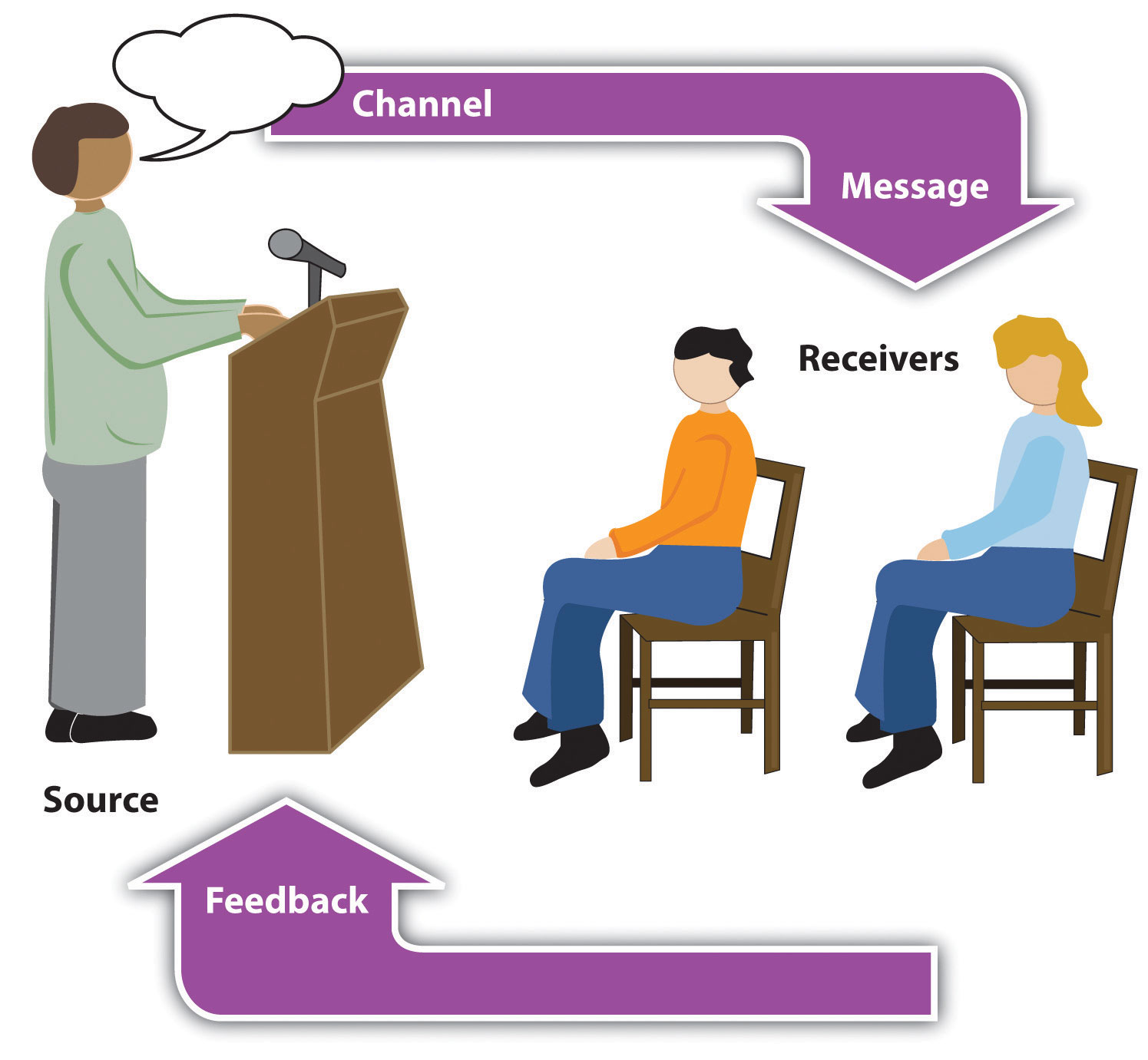

The interactional model of public speaking comes from the work of Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver.Shannon, C. E., & Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. The original model mirrored how radio and telephone technologies functioned and consisted of three primary parts: source, channel, and receiver. The sourceThe person(s) who originates a message. was the part of a telephone a person spoke into, the channelThe means by which a message is carried from one person to another (e.g., verbal, nonverbal, or mediated). was the telephone itself, and the receiverThe person(s) who takes delivery of a message. was the part of the phone where one could hear the other person. Shannon and Weaver also recognized that often there is static that interferes with listening to a telephone conversation, which they called noise.

Although there are a number of problems with applying this model to human communication, it does have some useful parallels to public speaking. In public speaking, the source is the person who is giving the speech, the channel is the speaker’s use of verbalThe use of words to elicit meaning in the mind of a receiver. and nonverbal communicationAny stimuli other than words that can potentially elicit meaning in the mind of a receiver., and the receivers are the audience members listening to the speech. As with a telephone call, a wide range of distractions (noiseAny internal or environmental factor that interferes with the ability to listen effectively. Some of these factors are physical, psychological, physiological, and semantic.) can inhibit an audience member from accurately attending to a speaker’s speech. Avoiding or adapting to these types of noise is an important challenge for public speakers.

Interactional Model

The interactional model of communication developed by Wilbur Schramm builds upon the linear model.Schramm, W. (1954). How communication works. In W. Schramm (Ed.), The process and effects of communication (pp. 3–26). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. Schramm added three major components to the Shannon and Weaver model. First, Schramm identified two basic processes of communication: encoding and decoding. EncodingThe process a source goes through when creating a message, adapting it to the receiver, and transmitting it across some source-selected channel. is what a source does when “creating a message, adapting it to the receiver, and transmitting it across some source-selected channel.”Wrench, J. S., McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (2008). Human communication in everyday life: Explanations and applications. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon, p. 17. When you are at home preparing your speech or standing in front of your classroom talking to your peers, you are participating in the encoding process.

The second major process is the decodingSensing a source’s message (through the five senses), interpreting the source’s message, and evaluating the source’s message. process, or “sensing (for example, hearing or seeing) a source’s message, interpreting the source’s message, evaluating the source’s message, and responding to the source’s message.”Wrench, J. S., McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (2008). Human communication in everyday life: Explanations and applications. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon, p. 17. Decoding is relevant in the public speaking context when, as an audience member, you listen to the words of the speech, pay attention to nonverbal behaviors of the speaker, and attend to any presentation aids that the speaker uses. You must then interpret what the speaker is saying.

Although interpreting a speaker’s message may sound easy in theory, in practice many problems can arise. A speaker’s verbal message, nonverbal communication, and mediatedThe use of some form of technology that intervenes between a source and a receiver of a message. presentation aids can all make a messageAny verbal or nonverbal stimulus that is meaningful to a receiver. either clearer or harder to understand. For example, unfamiliar vocabulary, speaking too fast or too softly, or small print on presentation aids may make it difficult for you to figure out what the speaker means. Conversely, by providing definitions of complex terms, using well-timed gestures, or displaying graphs of quantitative information, the speaker can help you interpret his or her meaning.

Once you have interpreted what the speaker is communicating, you then evaluate the message. Was it good? Do you agree or disagree with the speaker? Is a speaker’s argument logical? These are all questions that you may ask yourself when evaluating a speech.

The last part of decoding is “responding to a source’s message,” when the receiver encodes a message to send to the source. When a receiver sends a message back to a source, we call this process feedbackA receiver’s observable verbal and nonverbal responses to a source’s message.. Schramm talks about three types of feedback: direct, moderately direct, and indirect.Schramm, W. (1954). How communication works. In W. Schramm (Ed.), The process and effects of communication (pp. 3–26). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. The first type, direct feedback, occurs when the receiver directly talks to the source. For example, if a speech ends with a question-and-answer period, listeners will openly agree or disagree with the speaker. The second type of feedback, moderately direct, focuses on nonverbal messages sent while a source is speaking, such as audience members smiling and nodding their heads in agreement or looking at their watches or surreptitiously sending text messages during the speech. The final type of feedback, indirect, often involves a greater time gap between the actual message and the receiver’s feedback. For example, suppose you run for student body president and give speeches to a variety of groups all over campus, only to lose on student election day. Your audiences (the different groups you spoke to) have offered you indirect feedback on your message through their votes. One of the challenges you’ll face as a public speaker is how to respond effectively to audience feedback, particularly the direct and moderately direct forms of feedback you receive during your presentation.

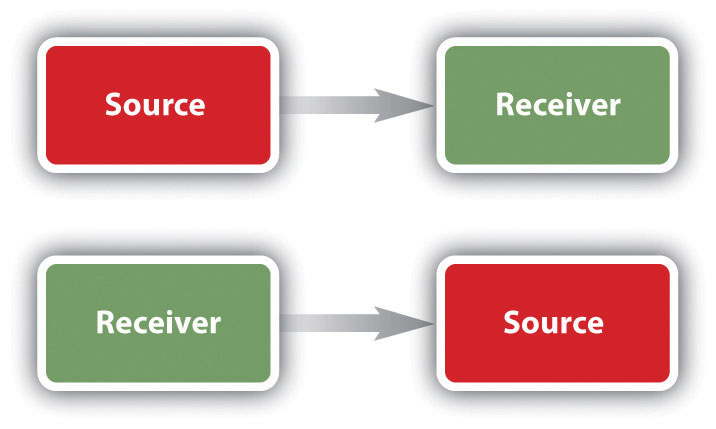

Transactional Model of Public Speaking

One of the biggest concerns that some people have with the interactional model of communication is that it tends to place people into the category of either source or receiver with no overlap. Even with Schramm’s model, encoding and decoding are perceived as distinct for sources and receivers. Furthermore, the interactional model cannot handle situations where multiple sources are interacting at the same time.Mortenson, C. D. (1972). Communication: The study of human communication. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. To address these weaknesses, Dean Barnlund proposed a transactional model of communication.Barnlund, D. C. (2008). A transactional model of communication. In C. D. Mortensen (Ed.), Communication theory (2nd ed., pp. 47–57). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. The basic premise of the transactional model is that individuals are sending and receiving messages at the same time. Whereas the interactional model has individuals engaging in the role of either source or receiver and the meaning of a message is sent from the source to the receiver, the transactional model assumes that meaning is cocreated by both people interacting together.

The idea that meanings are cocreated between people is based on a concept called the “field of experience.” According to West and Turner, a field of experience involves “how a person’s culture, experiences, and heredity influence his or her ability to communicate with another.”West, R., & Turner, L. H. (2010). Introducing communication theory: Analysis and application (4th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, p. 13. Our education, race, gender, ethnicity, religion, personality, beliefs, actions, attitudes, languages, social status, past experiences, and customs are all aspects of our field of experience, which we bring to every interaction. For meaning to occur, we must have some shared experiences with our audience; this makes it challenging to speak effectively to audiences with very different experiences from our own. Our goal as public speakers is to build upon shared fields of experience so that we can help audience members interpret our message.

Dialogic Theory of Public Speaking

Most people think of public speaking as engaging in a monologue where the speaker stands and delivers information and the audience passively listens. Based on the work of numerous philosophers, however, Ronald Arnett and Pat Arneson proposed that all communication, even public speaking, could be viewed as a dialogue.Arnett, R. C., & Arneson, P. (1999). Dialogic civility in a cynical age: Community, hope, and interpersonal relationships. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. The dialogic theoryTheory of public speaking that views public speaking as a dialogue between the speaker and her or his audience. is based on three overarching principles:

- Dialogue is more natural than monologue.

- Meanings are in people not words.

- Contexts and social situations impact perceived meanings.Bakhtin, M. (2001a). The problem of speech genres. (V. W. McGee, Trans., 1986). In P. Bizzell & B. Herzberg (Eds.), The rhetorical tradition (pp. 1227–1245). Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s. (Original work published in 1953.); Bakhtin, M. (2001b). Marxism and the philosophy of language. (L. Matejka & I. R. Titunik, Trans., 1973). In P. Bizzell & B. Herzberg (Eds.), The rhetorical tradition (pp. 1210–1226). Boston, MA: Medford/St. Martin’s. (Original work published in 1953).

Let’s look at each of these in turn.

Dialogue vs. Monologue

The first tenet of the dialogic perspective is that communication should be a dialogue and not a monologue. Lev Yakubinsky argued that even public speaking situations often turn into dialogues when audience members actively engage speakers by asking questions. He even claimed that nonverbal behavior (e.g., nodding one’s head in agreement or scowling) functions as feedback for speakers and contributes to a dialogue.Yakubinsky, L. P. (1997). On dialogic speech. (M. Eskin, Trans.). PMLA, 112(2), 249–256. (Original work published in 1923). Overall, if you approach your public speaking experience as a dialogue, you’ll be more actively engaged as a speaker and more attentive to how your audience is responding, which will, in turn, lead to more actively engaged audience members.

Meanings Are in People, Not Words

Part of the dialogic process in public speaking is realizing that you and your audience may differ in how you see your speech. Hellmut Geissner and Edith Slembeck (1986) discussed Geissner’s idea of responsibility, or the notion that the meanings of words must be mutually agreed upon by people interacting with each other.Geissner, H., & Slembek, E. (1986). Miteinander sprechen und handeln [Speak and act: Living and working together]. Frankfurt, Germany: Scriptor. If you say the word “dog” and think of a soft, furry pet and your audience member thinks of the animal that attacked him as a child, the two of you perceive the word from very different vantage points. As speakers, we must do our best to craft messages that take our audience into account and use audience feedback to determine whether the meaning we intend is the one that is received. To be successful at conveying our desired meaning, we must know quite a bit about our audience so we can make language choices that will be the most appropriate for the context. Although we cannot predict how all our audience members will interpret specific words, we do know that—for example—using teenage slang when speaking to the audience at a senior center would most likely hurt our ability to convey our meaning clearly.

Contexts and Social Situations

Russian scholar Mikhail Bahktin notes that human interactions take place according to cultural norms and rules.Bakhtin, M. (2001a). The problem of speech genres. (V. W. McGee, Trans., 1986). In P. Bizzell & B. Herzberg (Eds.), The rhetorical tradition (pp. 1227–1245). Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s. (Original work published in 1953.); Bakhtin, M. (2001b). Marxism and the philosophy of language. (L. Matejka & I. R. Titunik, Trans., 1973). In P. Bizzell & B. Herzberg (Eds.), The rhetorical tradition (pp. 1210–1226). Boston, MA: Medford/St. Martin’s. (Original work published in 1953). How we approach people, the words we choose, and how we deliver speeches are all dependent on different speaking contexts and social situations. On September 8, 2009, President Barack Obama addressed school children with a televised speech (http://www.whitehouse.gov/mediaresources/PreparedSchoolRemarks). If you look at the speech he delivered to kids around the country and then at his speeches targeted toward adults, you’ll see lots of differences. These dissimilar speeches are necessary because the audiences (speaking to kids vs. speaking to adults) have different experiences and levels of knowledge. Ultimately, good public speaking is a matter of taking into account the cultural background of your audience and attempting to engage your audience in a dialogue from their own vantage point.

Considering the context of a public speech involves thinking about four dimensions: physical, temporal, social-psychological, and cultural.DeVito, J. A. (2009). The interpersonal communication book (12th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Physical Dimension

The physical dimension of communication involves the real or touchable environment where communication occurs. For example, you may find yourself speaking in a classroom, a corporate board room, or a large amphitheater. Each of these real environments will influence your ability to interact with your audience. Larger physical spaces may require you to use a microphone and speaker system to make yourself heard or to use projected presentation aids to convey visual material.

How the room is physically decorated or designed can also impact your interaction with your audience. If the room is dimly lit or is decorated with interesting posters, audience members’ minds may start wandering. If the room is too hot, you’ll find people becoming sleepy. As speakers, we often have little or no control over our physical environment, but we always need to take it into account when planning and delivering our messages.

Temporal Dimension

According to Joseph DeVito, the temporal dimension “has to do not only with the time of day and moment in history but also with where a particular message fits into the sequence of communication events.”DeVito, J. A. (2009). The interpersonal communication book (12th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon, p. 13. The time of day can have a dramatic effect on how alert one’s audience is. Don’t believe us? Try giving a speech in front of a class around 12:30 p.m. when no one’s had lunch. It’s amazing how impatient audience members get once hunger sets in.

In addition to the time of day, we often face temporal dimensions related to how our speech will be viewed in light of societal events. Imagine how a speech on the importance of campus security would be interpreted on the day after a shooting occurred. Compare this with the interpretation of the same speech given at a time when the campus had not had any shootings for years, if ever.

Another element of the temporal dimension is how a message fits with what happens immediately before it. For example, if another speaker has just given an intense speech on death and dying and you stand up to speak about something more trivial, people may downplay your message because it doesn’t fit with the serious tone established by the earlier speech. You never want to be the funny speaker who has to follow an emotional speech where people cried. Most of the time in a speech class, you will have no advance notice as to what the speaker before you will be talking about. Therefore, it is wise to plan on being sensitive to previous topics and be prepared to ease your way subtly into your message if the situation so dictates.

Social-Psychological Dimension

The social-psychological dimension of context refers to “status relationships among participants, roles and games that people play, norms of the society or group, and the friendliness, formality, or gravity of the situation.”DeVito, J. A. (2009). The interpersonal communication book (12th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon, p. 14. You have to know the types of people in your audience and how they react to a wide range of messages.

Cultural Dimension

The final context dimension Joseph DeVito mentions is the cultural dimension.DeVito, J. A. (2009). The interpersonal communication book (12th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. When we interact with others from different cultures, misunderstandings can result from differing cultural beliefs, norms, and practices. As public speakers engaging in a dialogue with our audience members, we must attempt to understand the cultural makeup of our audience so that we can avoid these misunderstandings as much as possible.

Each of these elements of context is a challenge for you as a speaker. Throughout the rest of the book, we’ll discuss how you can meet the challenges presented by the audience and context and become a more effective public speaker in the process.

Key Takeaways

- Getting your message across to others effectively requires attention to message content, skill in communicating content, and your passion for the information presented.

- The interactional models of communication provide a useful foundation for understanding communication and outline basic concepts such as sender, receiver, noise, message, channel, encoding, decoding, and feedback. The transactional model builds on the interactional models by recognizing that people can enact the roles of sender and receiver simultaneously and that interactants cocreate meaning through shared fields of experience.

- The dialogic theory of public speaking understands public speaking as a dialogue between speaker and audience. This dialogue requires the speaker to understand that meaning depends on the speaker’s and hearer’s vantage points and that context affects how we must design and deliver our messages.

Exercises

- Draw the major models of communication on a piece of paper and then explain how each component is important to public speaking.

- When thinking about your first speech in class, explain the context of your speech using DeVito’s four dimensions: physical, temporal, social-psychological, and cultural. How might you address challenges posed by each of these four dimensions?

1.3 Chapter Exercises

End-of-Chapter Assessment

-

José is a widely sought-after speaker on the topic of environmental pollution. He’s written numerous books on the topic and is always seen as the “go-to” guy by news channels when the topic surfaces. What is José?

- thought leader

- innovator

- business strategist

- rhetorical expert

- intellectual capitalist

-

Fatima is getting ready for a speech she is delivering to the United Nations. She realizes that there are a range of relationships among her various audience members. Furthermore, the United Nations has a variety of norms that are specific to that context. Which of DeVito’s (2009) four aspects of communication context is Fatima concerned with?

- physical

- temporal

- social-psychological

- cultural

- rhetorical

Answer Key

- a

- c