This is “Pulse, Tempo, and Meter”, section 1.2 from the book Music Theory (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

1.2 Pulse, Tempo, and Meter

Learning Objectives

- Definitions of the elements of rhythmic organization.

- Perception of Tempo and commonly used terms.

- Mapping out meter (time signatures): the perception of Simple and Compound Time.

- How these elements interact in music.

We perceive the organization of time in music in terms of three fundamental elements, Pulse, Tempo, and Meter. Use prompts to assist you in understanding these elements:

- Pulse—“beat”: the background “heartbeat” of a piece of music.

- Tempo—“rate”: the relatively fast or slow speed at which we perceive the pulse in a piece of music.

- Meter—“ratio”: how durational values are assigned to represent the pulse are organized in discrete segments in a piece of music.

Pulse and Tempo

PulsePulse (or beat) is the regularly recurring background pulsation in music., or beat, is the regularly recurring underlying pulsation that we perceive that compels music to progress through time. Pulse makes us react kinesthetically to music: in other words, it compels motion. We tap our feet, we dance, we march, or we may just “feel” the pulse internally.

In a piece of music, some durational value is assigned to be the pulse. All other durations are proportionally related to that fundamental background pulse.

TempoTempo is the rate at which we perceive the pulse in time. This is indicated by metronome markings, pulse value markings and terms. (Latin: tempus-“time”) is the rate (or relative speed) at which the pulse flows through time. This is determined by numerous methods:

-

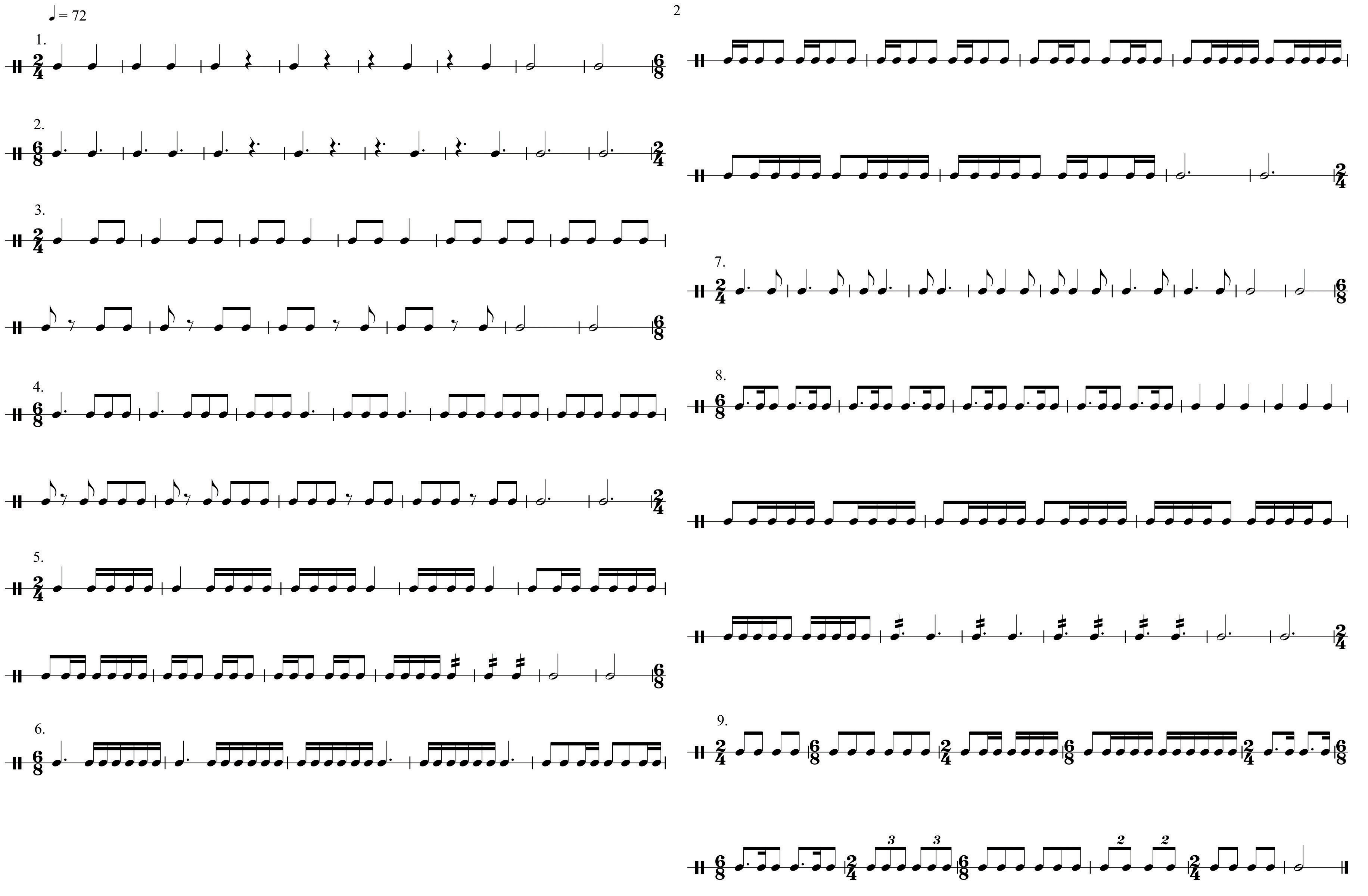

A metronome marking: for example, MM=120 means the pulse progresses at 120 beats per minute (two beats per second). Often, in practice, the background durational value will be drawn and assigned a metronomic value. (You will sometimes encounter the marking bpm, “beats per minute.”)

Figure 1.15 Metronome Marking and Pulse Marking

- Around the 17th Century (roughly!), Italian terms came to be used to indicate tempo. These terms were descriptive and therefore rather loosely interpreted as to exact tempo. These terms indicate a narrow “range” of metronomic speeds. For example, the term Andante means “going” or “a walking tempo.” This usually equates to roughly 76 beats per minute, but may be interpreted at a slightly faster or slightly slower pace.

-

In an attempt to refine these terms, to make them more precise, diminutives were added: Andantino indicates a slightly faster pace than Andante. Other modifiers came into common practice as well. For example, Andante con moto (“going, with motion”) is self-explanatory.

Beginning in the 19th Century, composers often used equivalent tempo and performance descriptions in their native languages, or mixed Italianate terms and vernacular terms within the same piece.

- It is important to understand that the use of these terms exceeded mere indications of relative speed. Often, they also carry the connotation of style or performance practice. For example, Allegro con brio (“lively, with fire or brilliance”) implies a stylistic manner of performance, not merely a rate at which the pulse progresses through time. Chapter 19 "Appendix A: Common Musical Terms" lists common terms and their commonly accepted meanings along with some equivalents in other languages.

Meter and Time Signatures

MeterMeter is the “ratio” of how many of what type of pulse values are grouped together. Simple Meter divides the pulse into two equal portions; Compound Meter divides the pulse into three equal portions., expressed in music as a time signature, determines:

- Which durational value is assigned to represent the fundamental background pulse;

- How these pulses are grouped together in discrete segments;

- How these pulses naturally subdivide into lesser durational values, and;

- The relative strength of pulses (perceived accents) within segments or groupings of pulses.Concerning accentuation of pulse, you will encounter the terms Arsis and Thesis, terms adapted from Hellenistic poetic meter. These have come to mean “upbeat” and “downbeat” respectively. These are nearly slang definitions or, at best, jargon. Arsis is best described as “preparatory,” hence perceived as a relatively weak pulse. Thesis is best described as “accentuated,” hence relatively strong. It is interesting to note that, at various times in the history of music, the meaning of these two terms has been reversed from time to time.

Time signaturesMeter is expressed as time signatures, indicating how many pulses (beats) are grouped together into cogent units. consist of two numbers, one over another, placed at the beginning of a composition. They may occur anywhere in a composition where a meter change is required. They are NEVER written as fractions!

Simple and Compound Meter

To understand meter fully, we must first determine the fundamental nature of the prevailing background pulse or beat. In given meters, we perceive beats as having the potential (or capacity) of being divided in two ways:

- The prevailing background pulse may be subdivided into two proportionally equal portions. Meters having this attribute are labeled Simple Meter (or Simple time).

- The prevailing background pulse may be subdivided into three proportionally equal portions. Meters having this attribute are labeled Compound Meter (Compound time).

We name meters according to two criteria:

- Is it Simple or Compound time?

- How many prevailing background pulses are grouped together?

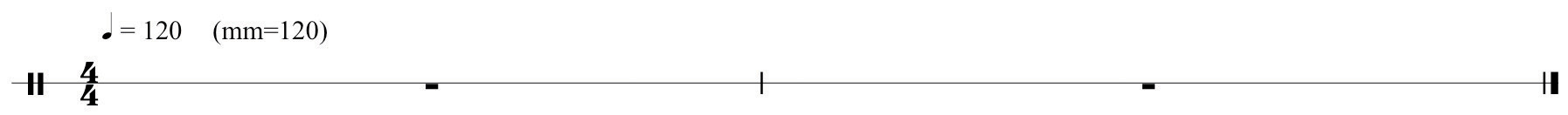

Figure 1.16 Simple and Compound Divisions of Given Pulses

So, a time signature wherein (a) the pulse subdivides into two portions, and (b) two pulses are grouped together is called Simple Duple. Three pulses grouped together, Simple Triple and so forth. A time signature wherein (a) the pulse subdivides into three portions, and (b) two pulses are grouped together is called Compound Duple, three pulses, Compound Triple, and so forth.

Figure 1.17 Time Signatures and Labels

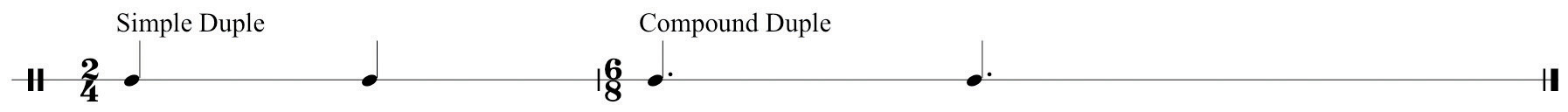

Simple Meter

Let us address simple meter first. Analyze this by answering two questions concerning the stated time signature:

- For the top number: “How many…?” In other words, how many prevailing background pulse values (or their relative equivalent values and/or rests) are grouped together?

- For the bottom number: “…of what kind?” In other words, what durational value has been assigned to represent the prevailing background pulse?

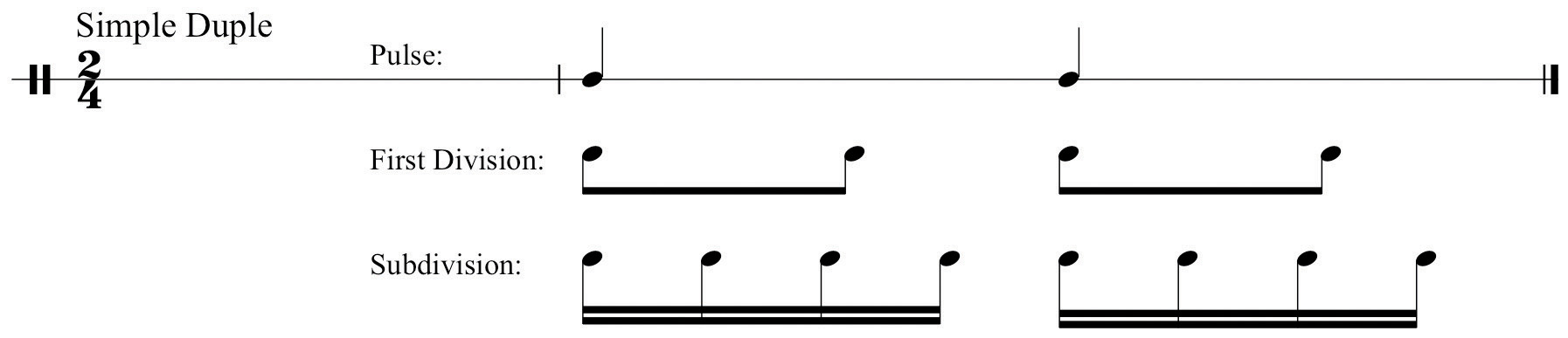

So the time signature has two quarter-notes grouped together, therefore, we label this as Simple Duple.

Figure 1.18 Typical Simple Meters

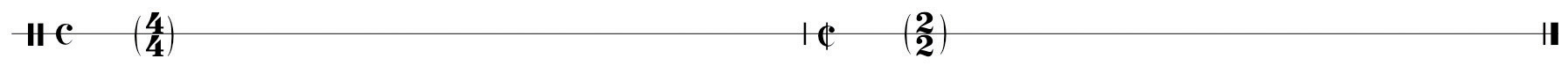

In Renaissance music, specialized symbols were employed that were the forerunner of time signatures. These symbols determined how relative durational values were held in proportion to one another. We continue to employ two holdovers from this system.

Figure 1.19 “Common Time” and “Cut Time”

“Common Time” and “Cut Time,” are slang terms. Other names for “Cut Time” are “March Time” and the proper name, Alla Breve.

The Time Signature Table

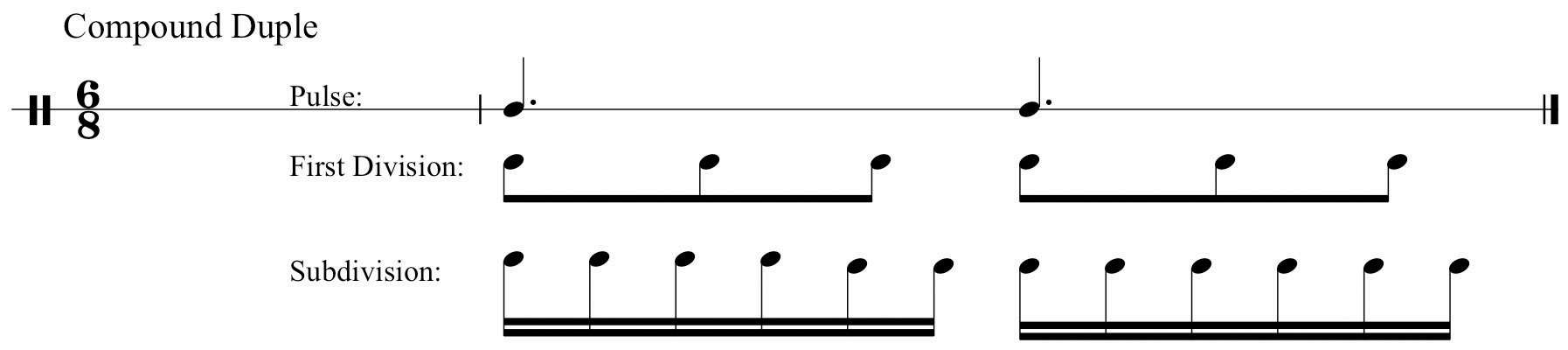

The characteristics of individual time signatures are perceived in multiple layers that can be reduced to three basic levels:

- The prevailing background Pulse or beat.

- First Division: the level wherein we determine if the pulse divides into two equal portions (simple meter) or three equal portions (compound meter).

- Subdivisions: how First Division values subdivide into proportionally smaller values.

Therefore, we can graph time signatures using the following table.

Table 1.1 Time Signature Table

| Pulse | (The fundamental background pulse.) |

| First Division | (The level determining pulse division into two portions or three portions.) |

| Subdivisions | (Subsequent divisions into smaller values.) |

Figure 1.20 Time Signature Table Example

Use this table to map out time signatures and their component organizational layers.

Compound Meter

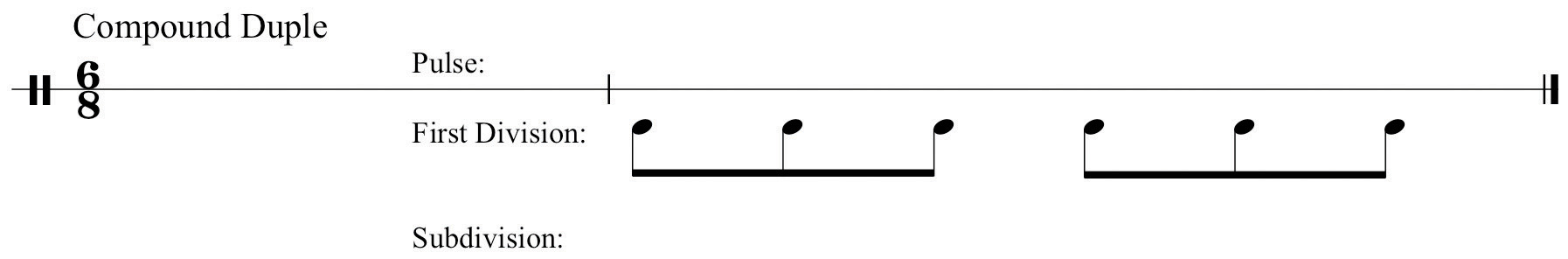

Understanding compound meters is somewhat more complex. Several preparatory statements will assist in comprehension:

-

Compound Meters have certain characteristics that will enable prompt recognition:

- The upper number is 3 or a multiple of 3.

- The prevailing background pulse must be a dotted value: remember, in compound meter, the pulse must have the capacity to divide into three equal portions.

- Subdivisions of the background pulse are usually grouped in sets of three by the use of beams (ligatures).

-

In theory, any Compound Meter may be perceived as Simple Meter,depending upon the tempo:

- If a tempo is slow enough, any compound time signature may be perceived as a simple meter.

- In practice, this is limited by style and context in compositions.

-

In Compound Meter, the written time signature represents the level of First Division,not Pulse:

- In order to find the pulse value in compound time signatures, use the Time Signature Table. List First Division values (the written time signature) in groupings of three.

- Sum these to the dotted value representing Pulse. List these accordingly in the Table.

As with Simple time signatures, let us employ the same Time Signature Table to graph Compound time signatures. Reviewing Statement 3 above, we will follow a slightly different procedure than that used for graphing Simple Meter:

-

For the Compound Duple time signature list six eighth-notes in two groupings of three in the First Division row:

Figure 1.21 Compound Meter, First Division Groupings

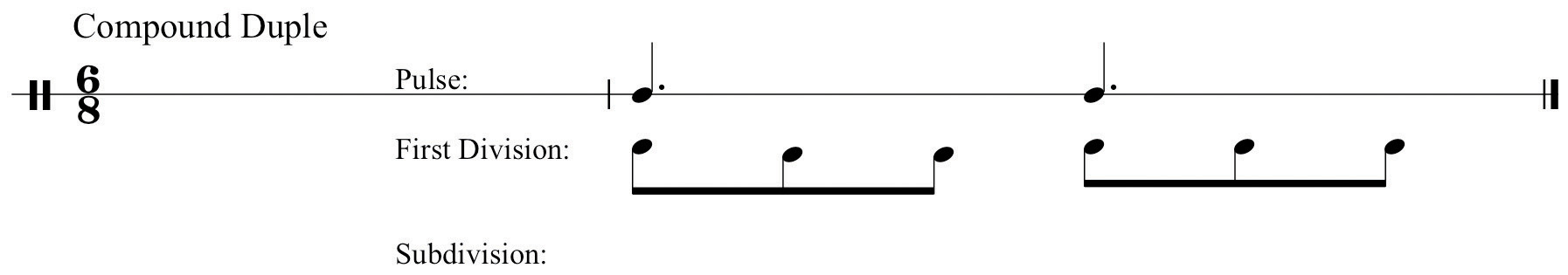

-

Next, sum these groupings of three into dotted values (“two eighth-notes equal a quarter-note, the additional quarter-note represented by a dot”); list the two resulting dotted quarter-notes in the Pulse row:

Figure 1.22 Sum to Find Compound Pulse Value

-

Lastly, draw subdivisions of the First Division values in the Subdivision row:

Figure 1.23 Subdivision

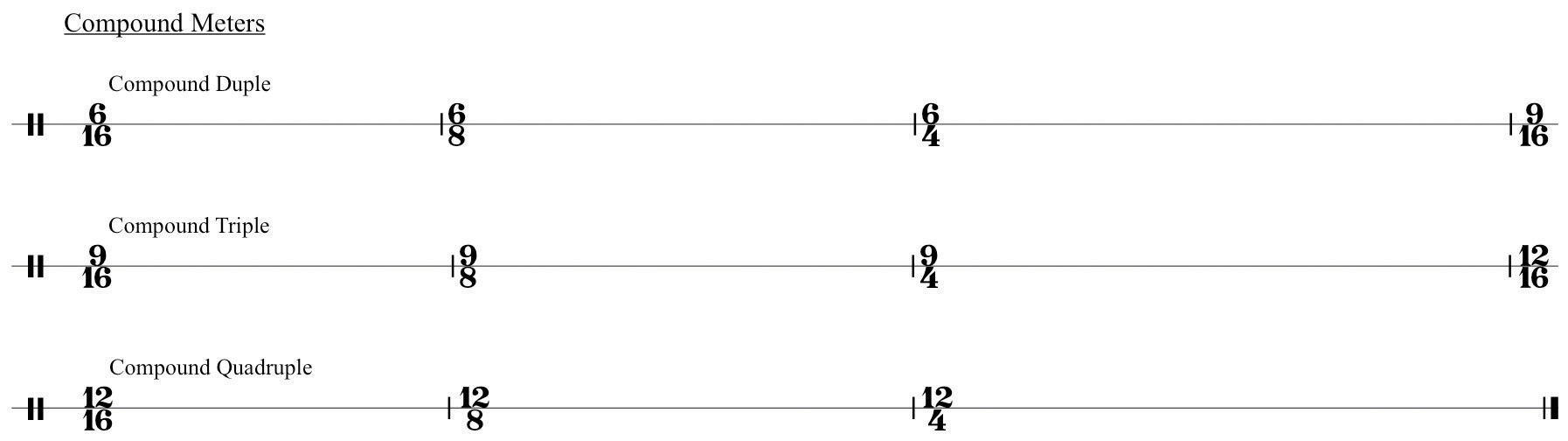

Below are typical compound meters and their respective labels.

Figure 1.24 Typical Compound Meters

Note that Simple meters divide all values into two subdivisions in each level of the Table. Compound meters divide the First Division level into three (see Statement 1 above). Subsequent subdivisions divide into two.

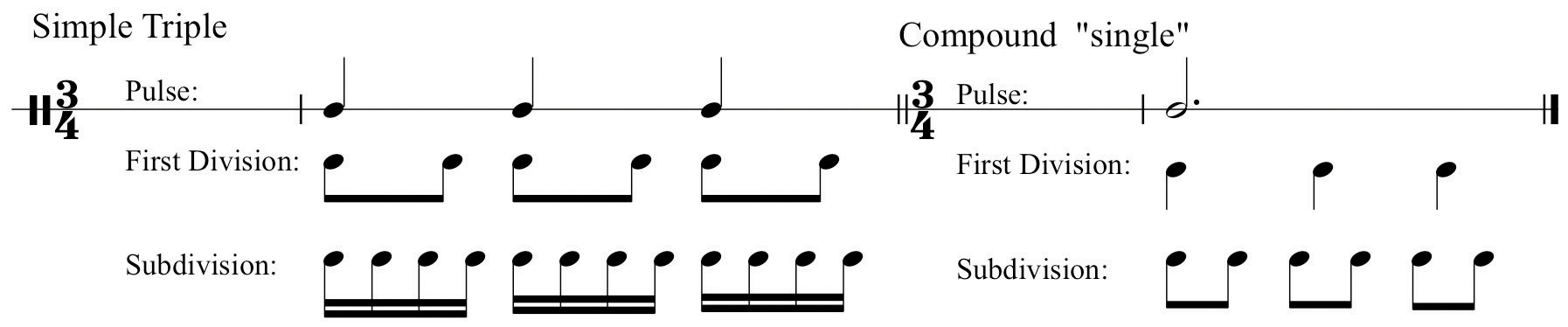

Simple Triple Interpreted as Compound Meter

Some Simple Triple time signatures may be perceived as either simple or compound, again depending upon tempo. In practice, this is a limited list: The time signatures:

may be perceived as Simple Triple if the tempo is relatively slow. In other words, you perceive the “lower number” of the time signature as the fundamental background pulse value. As the tempo for any of these becomes relatively faster, we cease to perceive the lower number as Pulse. Instead we perceive the lower number as the First Division of a Compound meter.

The Time Signature Table will show this:

Figure 1.25 Simple Triple, Compound “Single”

In the next section, these fundamental elements of sound, symbol, and time will be placed in full musical context by uniting them with common notational practices.

Key Takeaways

The student should be able to define and understand:

- Pulse (“beat”), Tempo (“rate”), and Meter (“ratio”).

- Simple Meter: recognizing and analyzing Simple Time Signatures.

- Compound Meter: recognizing and analyzing Compound Time Signatures.

- Time Signatures that may be perceived as either Simple or Compound and why they are so perceived.

- Using the Time Signature Table as a tool for graphing Time Signatures.

Exercises

-

Using the Time Signature Table, map out all examples of:

-

Simple Duple and Compound Duple.

Pulse First Division Subdivisions -

Simple Triple and Compound Triple.

Pulse First Division Subdivisions -

Simple Quadruple and Compound Quadruple.

Pulse First Division Subdivisions

Note: At the Subdivision level, draw one layer of subdivisions only.

-

-

Using the Time Signature Table map out the following time signatures as both Simple and Compound Meters:

-

Pulse First Division Subdivisions -

Pulse First Division Subdivisions -

Pulse First Division Subdivisions -

Pulse First Division Subdivisions

-

- In class (or some group), practice tapping a slow beat with your left foot. Against that beat tap two equal (“even”) divisions with your right hand (simple division). Next, keeping that same slow beat in your left foot, practice tapping three equal (“even”) divisions with your right hand (compound division). Lastly, switch hands and feet. Good luck.

-

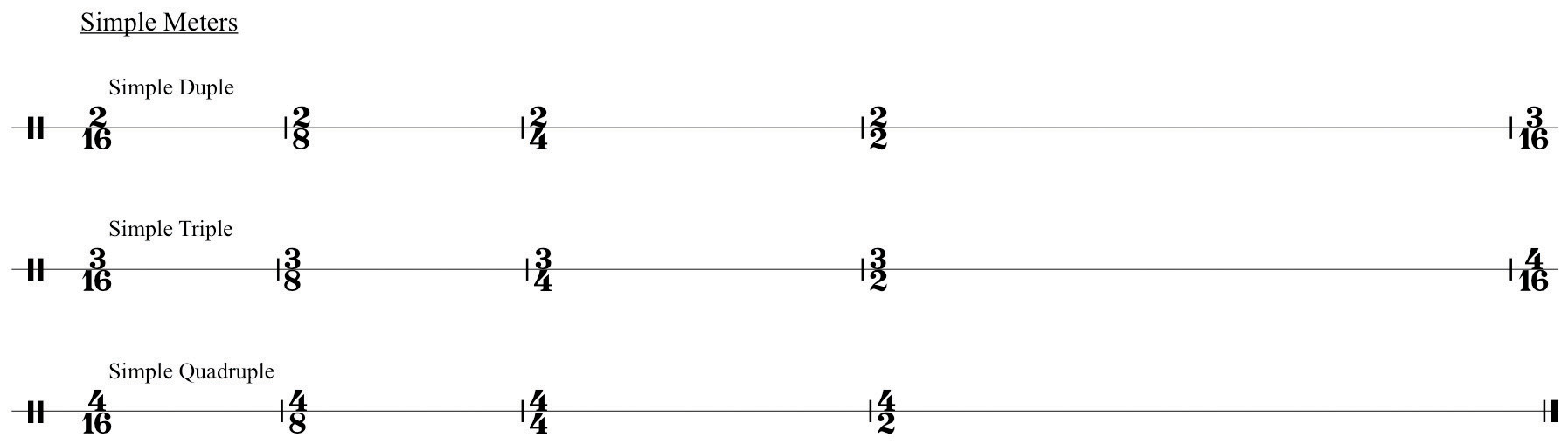

The following exercises alternate between simple duple and compound duple. Tap these rhythms while keeping the same constant background pulse. Practice each segment separately at first: then practice in sequence, switching from simple to compound time as you go.

Figure 1.26 Rhythm Drill