This is “Socialist Systems in Action”, section 20.2 from the book Microeconomics Principles (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

20.2 Socialist Systems in Action

Learning Objectives

- Describe the operation of the command socialist system in the Soviet Union, including its major problems.

- Explain how Yugoslavian-style socialism differed from that of the Soviet Union.

- Discuss the factors that brought an end to command socialist systems in much of the world.

The most important example of socialism was the economy of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the Soviet Union. The Russian Revolution succeeded in 1917 in overthrowing the czarist regime that had ruled the Russian Empire for centuries. Leaders of the revolution created the Soviet Union in its place and sought to establish a socialist state based on the ideas of Karl Marx.

The leaders of the Soviet Union faced a difficulty in using Marx’s writings as a foundation for a socialist system. He had sought to explain why capitalism would collapse; he had little to say about how the socialist system that would replace it would function. He did suggest the utopian notion that, over time, there would be less and less need for a government and the state would wither away. But his writings did not provide much of a blueprint for running a socialist economic system.

Lacking a guide for establishing a socialist economy, the leaders of the new regime in Russia struggled to invent one. In 1917, Lenin attempted to establish what he called “war communism.” The national government declared its ownership of most firms and forced peasants to turn over a share of their output to the government. The program sought to eliminate the market as an allocative mechanism; government would control production and distribution. The program of war communism devastated the economy. In 1921, Lenin declared a New Economic Policy. It returned private ownership to some sectors of the economy and reinstituted the market as an allocative mechanism.

Lenin’s death in 1924 precipitated a power struggle from which Joseph Stalin emerged victorious. It was under Stalin that the Soviet economic system was created. Because that system served as a model for most of the other command socialist systems that emerged, we shall examine it in some detail. We shall also examine an intriguing alternative version of socialism that was created in Yugoslavia after World War II.

Command Socialism in the Soviet Union

Stalin began by seizing virtually all remaining privately-owned capital and natural resources in the country. The seizure was a brutal affair; he eliminated opposition to his measures through mass executions, forced starvation of whole regions, and deportation of political opponents to prison camps. Estimates of the number of people killed during Stalin’s centralization of power range in the tens of millions. With the state in control of the means of production, Stalin established a rigid system in which a central administration in Moscow determined what would be produced.

The justification for the brutality of Soviet rule lay in the quest to develop “socialist man.” Leaders of the Soviet Union argued that the tendency of people to behave in their own self-interest was a by-product of capitalism, not an inherent characteristic of human beings. A successful socialist state required that the preferences of people be transformed so that they would be motivated by the collective interests of society, not their own self-interest. Propaganda was widely used to reinforce a collective identity. Those individuals who were deemed beyond reform were likely to be locked up or executed.

The political arm of command socialism was the Communist party. Party officials participated in every aspect of Soviet life in an effort to promote the concept of socialist man and to control individual behavior. Party leaders were represented in every firm and in every government agency. Party officials charted the general course for the economy as well.

A planning agency, Gosplan, determined the quantities of output that key firms would produce each year and the prices that would be charged. Other government agencies set output levels for smaller firms. These determinations were made in a series of plans. A 1-year plan specified production targets for that year. Soviet planners also developed 5-year and 20-year plans.

Managers of state-owned firms were rewarded on the basis of their ability to meet the annual quotas set by the Gosplan. The system of quotas and rewards created inefficiency in several ways. First, no central planning agency could incorporate preferences of consumers and costs of factors of production in its decisions concerning the quantity of each good to produce. Decisions about what to produce were made by political leaders; they were not a response to market forces. Further, planners could not select prices at which quantities produced would clear their respective markets. In a market economy, prices adjust to changes in demand and supply. Given that demand and supply are always changing, it is inconceivable that central planners could ever select market-clearing prices. Soviet central planners typically selected prices for consumer goods that were below market-clearing levels, causing shortages throughout the economy. Changes in prices were rare.

Plant managers had a powerful incentive for meeting their quotas; they could expect bonuses equal to about 35% of their base salary for producing the quantities required of their firms. Those who exceeded their quotas could boost this to 50%. In addition, successful managers were given vacations, better apartments, better medical care, and a host of other perquisites. Managers thus had a direct interest in meeting their quotas; they had no incentive to select efficient production techniques or to reduce costs.

Perhaps most important, there was no incentive for plant managers to adopt new technologies. A plant implementing a new technology risked start-up delays that could cause it to fall short of its quota. If a plant did succeed in boosting output, it was likely to be forced to accept even larger quotas in the future. A plant manager who introduced a successful technology would only be slapped with tougher quotas; if the technology failed, he or she would lose a bonus. With little to gain and a great deal to lose, Soviet plant managers were extremely reluctant to adopt new technologies. Soviet production was, as a result, characterized by outdated technologies. When the system fell in 1991, Soviet manufacturers were using production methods that had been obsolete for decades in other countries.

Centrally controlled systems often generated impressive numbers for total output but failed in satisfying consumer demands. Gosplan officials, recognizing that Soviet capital was not very productive, ordered up a lot of it. The result was a heavy emphasis on unproductive capital goods and relatively little production of consumer goods. On the eve of the collapse of the Soviet Union, Soviet economists estimated that per capita consumption was less than one-sixth of the U.S. level.

The Soviet system also generated severe environmental problems. In principle, a socialist system should have an advantage over a capitalist system in allocating environmental resources for which private property rights are difficult to define. Because a socialist government owns all capital and natural resources, the ownership problem is solved. The problem in the Soviet system, however, came from the labor theory of value. Since natural resources are not produced by labor, the value assigned to them was zero. Soviet plant managers thus had no incentive to limit their exploitation of environmental resources, and terrible environmental tragedies were common.

Systems similar to that created in the Soviet Union were established in other Soviet bloc countries as well. The most important exceptions were Yugoslavia, which is discussed in the next section, and China, which started with a Soviet-style system and then moved away from it. The Chinese case is examined later in this chapter.

Yugoslavia: Another Socialist Experiment

Although the Soviet Union was able to impose a system of command socialism on nearly all the Eastern European countries it controlled after World War II, Yugoslavia managed to forge its own path. Yugoslavia’s communist leader, Marshal Tito, charted an independent course, accepting aid from Western nations such as the United States and establishing a unique form of socialism that made greater use of markets than the Soviet-style systems did. Most important, however, Tito quickly moved away from the centralized management style of the Soviet Union to a decentralized system in which workers exercised considerable autonomy.

In the Yugoslav system, firms with five or more employees were owned by the state but made their own decisions concerning what to produce and what prices to charge. Workers in these firms elected their managers and established their own systems for sharing revenues. Each firm paid a fee for the use of its state-owned capital. In effect, firms operated as labor cooperatives. Firms with fewer than five employees could be privately owned and operated.

Economic performance in Yugoslavia was impressive. Living standards there were generally higher than those in other Soviet bloc countries. The distribution of income was similar to that of command socialist economies; it was generally more equal than distributions achieved in market capitalist economies. The Yugoslav economy was plagued, however, by persistent unemployment, high inflation, and increasing disparities in regional income levels.

Yugoslavia began breaking up shortly after command socialist systems began falling in Eastern Europe. It had been a country of republics and provinces with uneasy relationships among them. Tito had been the glue that held them together. After his death, the groups began to move apart and a number of countries have formed out of what was once Yugoslavia, in several cases accompanied by war. They all seem to be moving in the market capitalist direction, with Slovenia and Macedonia leading the way. Over time, the others—Croatia, Bosnia, and Herzegovina, and even Serbia and Montenegra–have been following suit.

Evaluating Economic Performance Under Socialism

Soviet leaders placed great emphasis on Marx’s concept of the inevitable collapse of capitalism. While they downplayed the likelihood of a global revolution, they argued that the inherent superiority of socialism would gradually become apparent. Countries would adopt the socialist model in order to improve their living standards, and socialism would gradually assert itself as the dominant world system.

One key to achieving the goal of a socialist world was to outperform the United States economically. Stalin promised in the 1930s that the Soviet economy would surpass that of the United States within a few decades. The goal was clearly not achieved. Indeed, it was the gradual realization that the command socialist system could not deliver high living standards that led to the collapse of the old system.

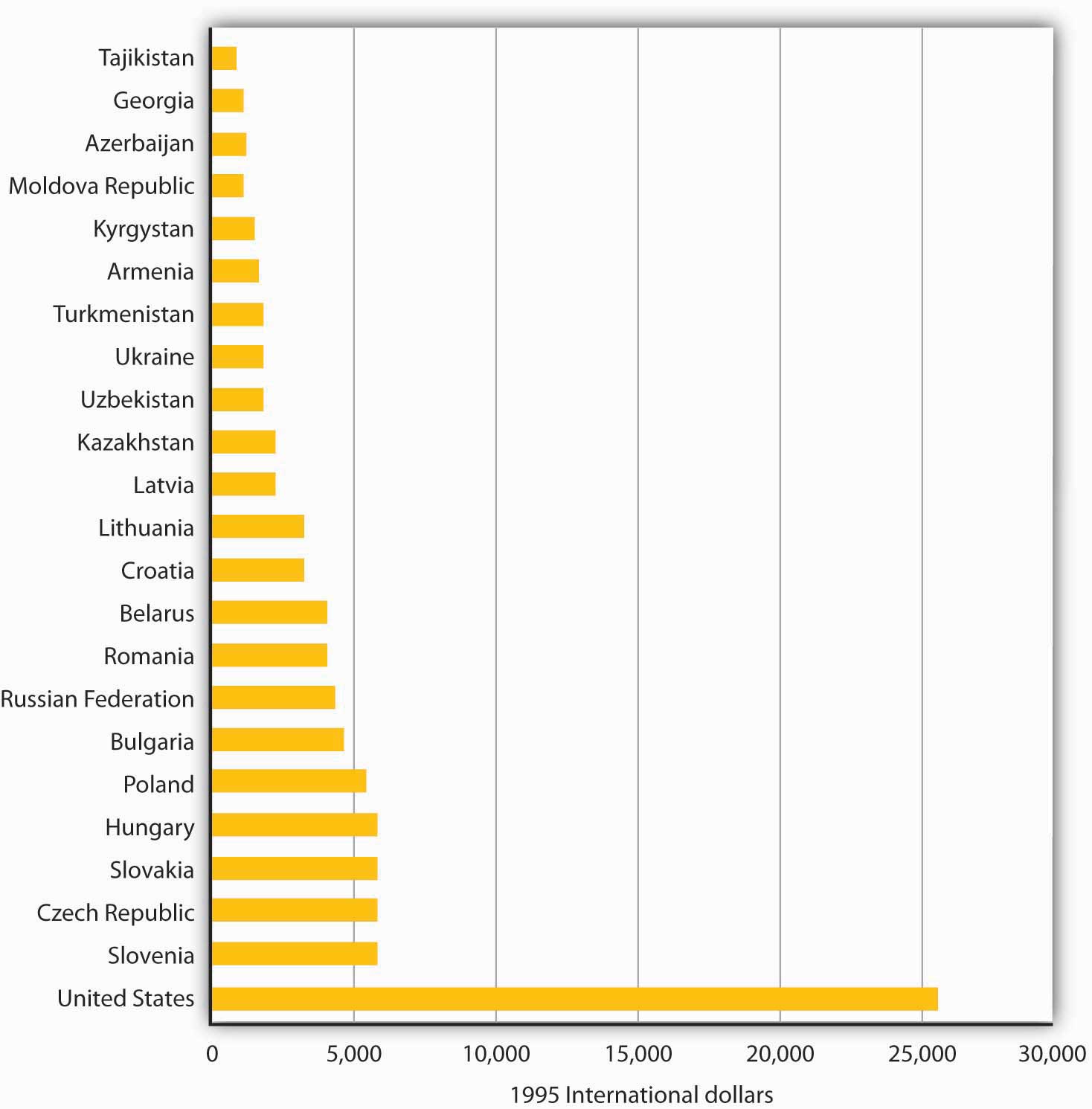

Figure 20.1 "Per Capita Output in Former Soviet Bloc States and in the United States, 1995" shows the World Bank’s estimates of per capita output, measured in dollars of 1995 purchasing power, for the republics that made up the Soviet Union, for the Warsaw Pact nations of Eastern Europe for which data are available, and for the United States in 1995. Nations that had operated within the old Soviet system had quite low levels of per capita output. Living standards were lower still, given that these nations devoted much higher shares of total output to investment and to defense than did the United States.

Figure 20.1 Per Capita Output in Former Soviet Bloc States and in the United States, 1995

Per capita output was far lower in the former republics of the Soviet Union and in Warsaw Pact countries in 1995 than in the United States. All values are measured in units of equivalent purchasing power.

Source: United Nations, Human Development Report, 1998.

Ultimately, it was the failure of the Soviet system to deliver living standards on a par with those achieved by market capitalist economies that brought the system down. Market capitalist economic systems create incentives to allocate resources efficiently; socialist systems do not. Of course, a society may decide that other attributes of a socialist system make it worth retaining. But the lesson of the 1980s was that few that had lived under command socialist systems wanted to continue to do so.

Key Takeaways

- In the Soviet Union a central planning agency, Gosplan, set output quotas for enterprises and determined prices.

- The Soviet central planning system was highly inefficient. Sources of this inefficiency included failure to incorporate consumer preferences into decisions about what to produce, failure to take into account costs of factors of production, setting of prices without regard to market equilibrium, lack of incentives for incorporating new technologies, overemphasis on capital goods production, and inattention to environmental problems.

- Yugoslavia developed an alternative system of socialism in which firms were run by their workers as labor cooperatives.

- It was the realization that command socialist systems could not deliver high living standards that contributed to their collapse.

Try It!

What specific problem of a command socialist system does each of the cartoons in the Case in Point parodying that system highlight?

Case in Point: Socialist Cartoons

These cartoons came from the Soviet press. Soviet citizens were clearly aware of many of the problems of their planned system.

“But where is the equipment that was sent to us?” “Which year are you talking about?” |

“But Santa, it’s winter, so we asked for boots for our son!” “I know, but the only thing available in the state store was a pair of sandals.” |

“Why are they sending us new technology when the old still works?” |

Answer to Try It!

The first cartoon shows the inefficiency that resulted because of the failure to take into account the costs of factors of production. The second cartoon shows the difficulty involved in getting business to incorporate new technologies. The third shows the system’s failure to respond to consumers’ demands.