This is “Monopsony and the Minimum Wage”, section 14.2 from the book Microeconomics Principles (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

14.2 Monopsony and the Minimum Wage

Learning Objectives

- Compare the impact of a minimum wage on employment in the case where the labor market is perfectly competitive to the case of a monopsony labor market.

- Discuss the debate among economists concerning the impact of raising the minimum wage.

We have seen that wages will be lower in monopsony than in otherwise similar competitive labor markets. In a competitive market, workers receive wages equal to their MRPs. Workers employed by monopsony firms receive wages that are less than their MRPs. This fact suggests sharply different conclusions for the analysis of minimum wages in competitive versus monopsony conditions.

In a competitive market, the imposition of a minimum wage above the equilibrium wage necessarily reduces employment, as we learned in the chapter on perfectly competitive labor markets. In a monopsony market, however, a minimum wage above the equilibrium wage could increase employment at the same time as it boosts wages!

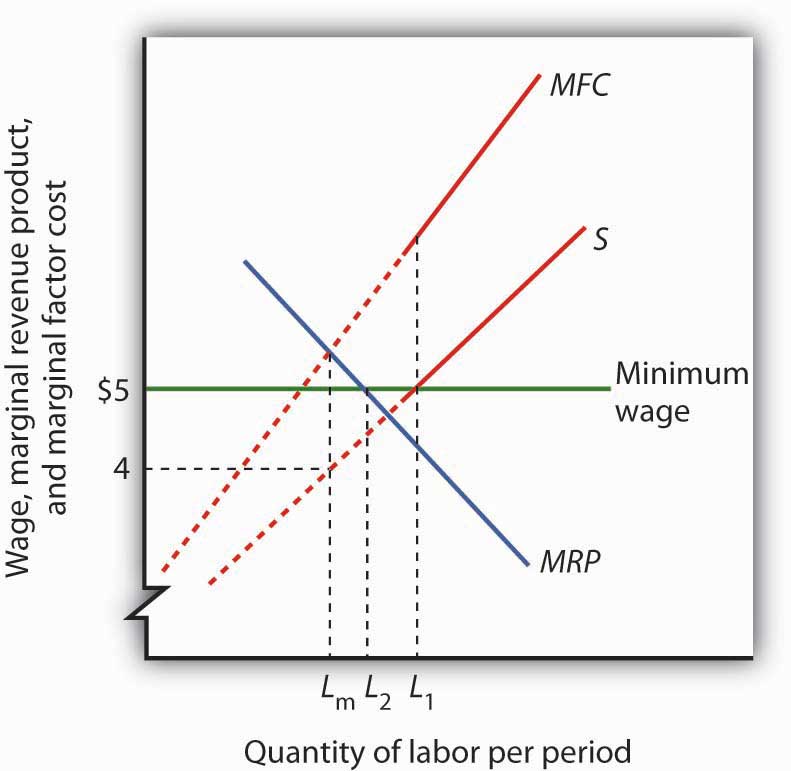

Figure 14.5 "Minimum Wage and Monopsony" shows a monopsony employer that faces a supply curve, S, from which we derive the marginal factor cost curve, MFC. The firm maximizes profit by employing Lm units of labor and paying a wage of $4 per hour. The wage is below the firm’s MRP.

Figure 14.5 Minimum Wage and Monopsony

A monopsony employer faces a supply curve S, a marginal factor cost curve MFC, and a marginal revenue product curve MRP. It maximizes profit by employing Lm units of labor and paying a wage of $4 per hour. The imposition of a minimum wage of $5 per hour makes the dashed sections of the supply and MFC curves irrelevant. The marginal factor cost curve is thus a horizontal line at $5 up to L1 units of labor. MRP and MFC now intersect at L2 so that employment increases.

Now suppose the government imposes a minimum wage of $5 per hour; it is illegal for firms to pay less. At this minimum wage, L1 units of labor are supplied. To obtain any smaller quantity of labor, the firm must pay the minimum wage. That means that the section of the supply curve showing quantities of labor supplied at wages below $5 is irrelevant; the firm cannot pay those wages. Notice that the section of the supply curve below $5 is shown as a dashed line. If the firm wants to hire more than L1 units of labor, however, it must pay wages given by the supply curve.

Marginal factor cost is affected by the minimum wage. To hire additional units of labor up to L1, the firm pays the minimum wage. The additional cost of labor beyond L1 continues to be given by the original MFC curve. The MFC curve thus has two segments: a horizontal segment at the minimum wage for quantities up to L1 and the solid portion of the MFC curve for quantities beyond that.

The firm will still employ labor up to the point that MFC equals MRP. In the case shown in Figure 14.5 "Minimum Wage and Monopsony", that occurs at L2. The firm thus increases its employment of labor in response to the minimum wage. This theoretical conclusion received apparent empirical validation in a study by David Card and Alan Krueger that suggested that an increase in New Jersey’s minimum wage may have increased employment in the fast food industry. That conclusion became an important political tool for proponents of an increase in the minimum wage. The validity of those results has come under serious challenge, however, and the basic conclusion that a higher minimum wage would increase unemployment among unskilled workers in most cases remains the position of most economists. The discussion in the Case in Point summarizes the debate.

Key Takeaways

- In a competitive labor market, an increase in the minimum wage reduces employment and increases unemployment.

- A minimum wage could increase employment in a monopsony labor market at the same time it increases wages.

- Some economists argue that the monopsony model characterizes all labor markets and that this justifies a national increase in the minimum wage.

- Most economists argue that a nationwide increase in the minimum wage would reduce employment among low-wage workers.

Try It!

Using the data in Note 14.5 "Try It!", suppose a minimum wage of $40 per day is imposed. How will this affect the firm’s use of labor?

Case in Point: The Monopsony-Minimum Wage Controversy

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

While the imposition of a minimum wage on a monopsony employer could increase employment and wages at the same time, the possibility is generally regarded as empirically unimportant, given the rarity of cases of monopsony power in labor markets. However, some studies have found that increases in the minimum wage have led to either increased employment or to no significant reductions in employment. These results appear to contradict the competitive model of demand and supply in the labor market, which predicts that an increase in the minimum wage will lead to a reduction in employment and an increase in unemployment.

The study that sparked the controversy was an analysis by David Card and Alan Krueger of employment in the fast food industry in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. New Jersey increased its minimum wage to $5.05 per hour in 1992, when the national minimum wage was $4.25 per hour. The two economists surveyed 410 fast food restaurants in the Burger King, KFC, Roy Rogers, and Wendy’s chains just before New Jersey increased its minimum and again 10 months after the increase.

There was no statistically significant change in employment in the New Jersey franchises, but employment fell in the Pennsylvania franchises. Thus, employment in the New Jersey franchises “rose” relative to employment in the Pennsylvania franchises. Card and Krueger’s results were widely interpreted as showing an increase in employment in New Jersey as a result of the increase in the minimum wage there.

Do minimum wages reduce employment or not? Some economists interpreted the Card and Krueger results as demonstrating widespread monopsony power in the labor market. Economist Alan Manning notes that the competitive model implies that a firm that pays a penny less than the market equilibrium wage will have zero employees. But, Mr. Manning notes that there are non-wage attributes to any job that, together with the cost of changing jobs, result in individual employers facing upward-sloping supply curves for labor and thus giving them monopsony power. And, as we have seen, a firm with monopsony power may respond to an increase in the minimum wage by increasing employment.

The difficulty with implementing this conclusion on a national basis is that, even if firms do have a degree of monopsony power, it is impossible to determine just how much power any one firm has and by how much the minimum wage could be increased for each firm. As a result, even if it were true that firms had such monopsony power, it would not follow that an increase in the minimum wage would be appropriate.

Even the finding that an increase in the minimum wage may not reduce employment has been called into question. First, there are many empirical studies that suggest that increases in the minimum wage do reduce employment. For example, a recent study of employment in the restaurant industry by Chicago Federal Reserve Bank economists Daniel Aaronson and Eric French concluded that a 10% increase in the minimum wage would reduce employment among unskilled restaurant workers by 2 to 4%. This finding was more in line with other empirical work. Further, economists point out that jobs have nonwage elements. Hours of work, working conditions, fellow employees, health insurance, and other fringe benefits of working can all be adjusted by firms in response to an increase in the minimum wage. Dwight Lee, an economist at the University of Georgia, argues that as a result, an increase in the minimum wage may not reduce employment but may reduce other fringe benefits that workers value more highly than wages themselves. So, an increase in the minimum wage may make even workers who receive higher wages worse off. One indicator that suggests that higher minimum wages may reduce the welfare of low income workers is that participation in the labor force by teenagers has been shown to fall as a result of higher minimum wages. If the opportunity to earn higher wages reduces the number of teenagers seeking those wages, it may indicate that low-wage work has become less desirable.

In short, the possibility that higher minimum wages might not reduce employment among low-wage workers does not necessarily mean that higher minimum wages improve the welfare of low income workers. Evidence that casts doubt on the proposition that higher minimum wages reduce employment does not remove many economists’ doubt that higher minimum wages would be a good policy.

Sources: Daniel Aaronson and Eric French, “Employment Effects of the Minimum Wage,” Journal of Labor Economics, January 2007, 25(1), 167–200; David Card and Alan B. Krueger, “Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast-Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania,” American Economic Review, 84 (1994): 772–93; Chris Dillow, “Minimum Wage Myths,” Economic Affairs, 20(1) (March 2000): 47–52; Dwight R. Lee, “The Minimum Wage Can Harm Workers by Reducing Unemployment,” Journal of Labor Research, 25(4) (Fall 2004); Andrew Leigh, “Employment Effects of Minimum Wages: Evidence from a Quasi-Experiment,” The Australian Economic Review, 36 (2003): 361–73; Andrew Leigh, “Employment Effects of Minimum Wages: Evidence from a Quasi-Experiment—Erratum,” The Australian Economic Review, 37(1): 102–5; Alan Manning, “Monopsony and the Efficiency of Labour Market Interventions,” Labour Economics, 11(2) (April 2004): 145–63; Walter J. Wessels, “Does the Minimum Wage Drive Teenagers Out of the Labor Force?” Journal of Labor Research, 26(1) (Winter 2005): 169–176.

Answer to Try It! Problem

The imposition of a minimum wage of $40 per day makes the MFC curve a horizontal line at $40, up to the S curve. In this case, the firm adds a fourth worker and pays the required wage, $40.