This is “Labor Markets at Work”, section 12.3 from the book Microeconomics Principles (v. 2.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

12.3 Labor Markets at Work

Learning Objectives

- Explain and illustrate how wage and employment levels are determined in a perfectly competitive market and for an individual firm within that market.

- Describe the forces that can raise or lower the equilibrium wage in a competitive market and illustrate these processes.

- Describe the ways that government can increase wages and incomes.

We have seen that a firm’s demand for labor depends on the marginal product of labor and the price of the good the firm produces. We add the demand curves of individual firms to obtain the market demand curve for labor. The supply curve for labor depends on variables such as population and worker preferences. Supply in a particular market depends on variables such as worker preferences, the skills and training a job requires, and wages available in alternative occupations. Wages are determined by the intersection of demand and supply.

Once the wage in a particular market has been established, individual firms in perfect competition take it as given. Because each firm is a price taker, it faces a horizontal supply curve for labor at the market wage. For one firm, changing the quantity of labor it hires does not change the wage. In the context of the model of perfect competition, buyers and sellers are price takers. That means that a firm’s choices in hiring labor do not affect the wage.

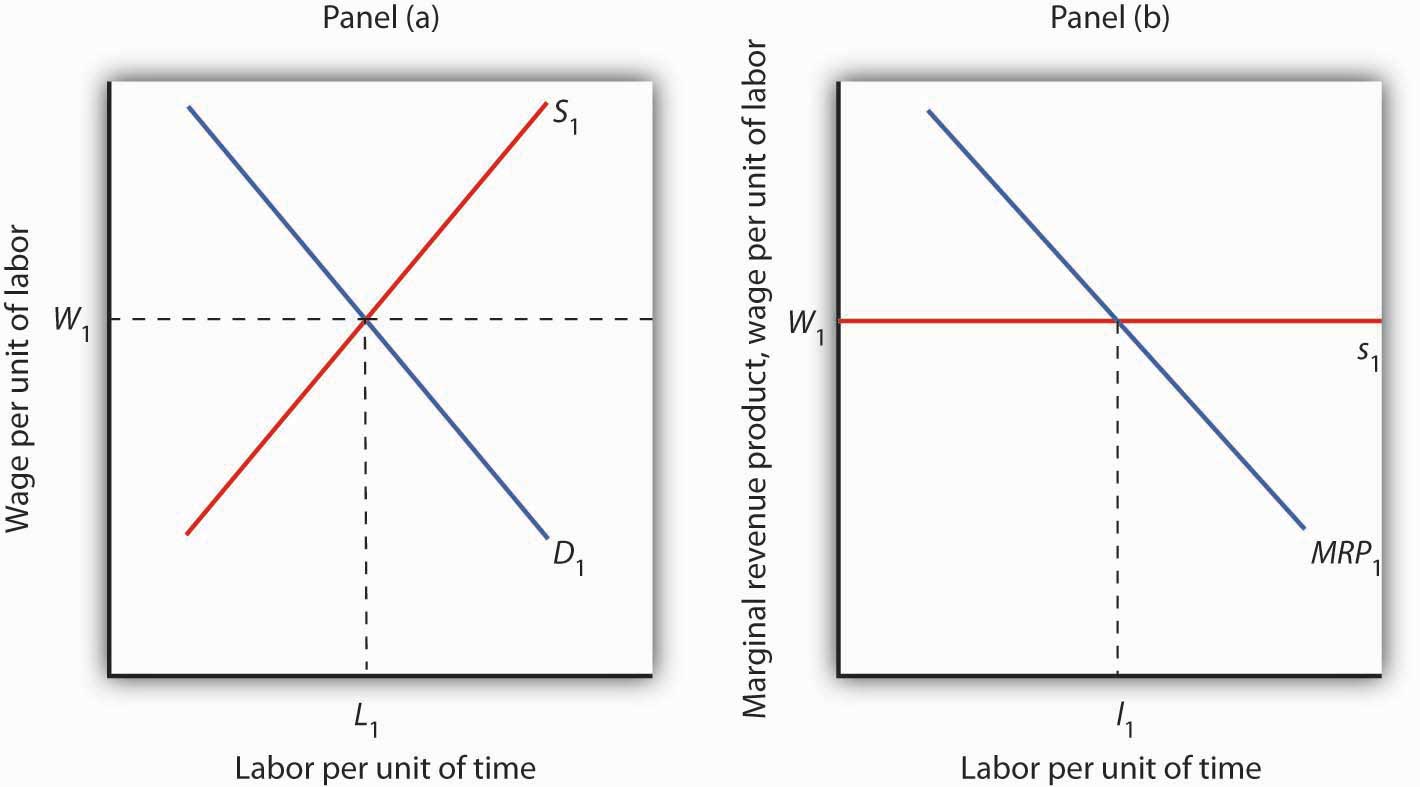

The operation of labor markets in perfect competition is illustrated in Figure 12.7 "Wage Determination and Employment in Perfect Competition". The wage W1 is determined by the intersection of demand and supply in Panel (a). Employment equals L1 units of labor per period. An individual firm takes that wage as given; it is the supply curve s1 facing the firm. This wage also equals the firm’s marginal factor cost. The firm hires l1 units of labor, a quantity determined by the intersection of its marginal revenue product curve for labor MRP1 and the supply curve s1. We use lowercase letters to show quantity for a single firm and uppercase letters to show quantity in the market.

Figure 12.7 Wage Determination and Employment in Perfect Competition

Wages in perfect competition are determined by the intersection of demand and supply in Panel (a). An individual firm takes the wage W1 as given. It faces a horizontal supply curve for labor at the market wage, as shown in Panel (b). This supply curve s1 is also the marginal factor cost curve for labor. The firm responds to the wage by employing l1 units of labor, a quantity determined by the intersection of its marginal revenue product curve MRP1 and its supply curve s1.

Changes in Demand and Supply

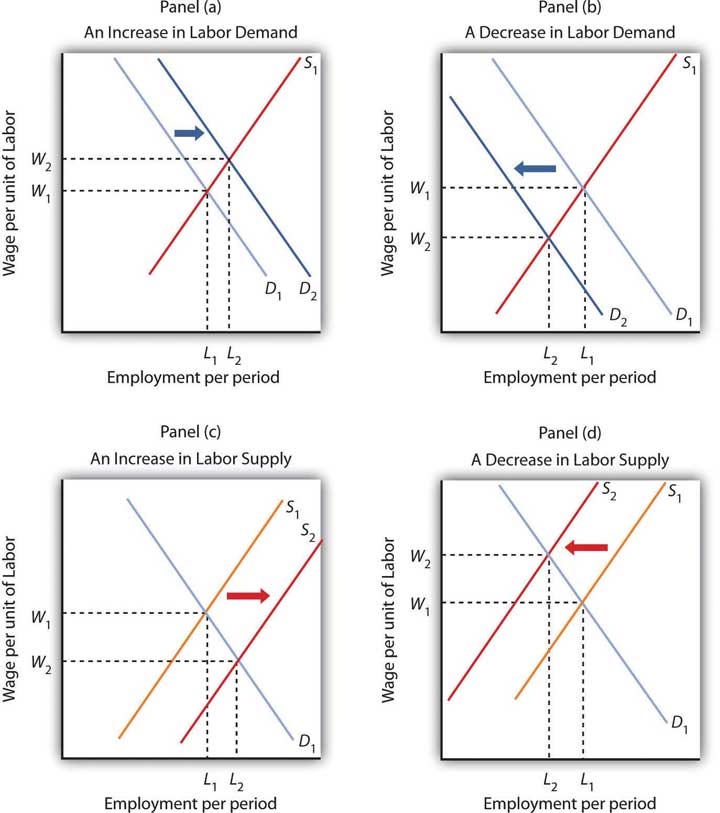

If wages are determined by demand and supply, then changes in demand and supply should affect wages. An increase in demand or a reduction in supply will raise wages; an increase in supply or a reduction in demand will lower them.

Panel (a) of Figure 12.8 "Changes in the Demand for and Supply of Labor" shows how an increase in the demand for labor affects wages and employment. The shift in demand to D2 pushes the wage to W2 and boosts employment to L2. Such an increase implies that the marginal product of labor has increased, that the number of firms has risen, or that the price of the good the labor produces has gone up. As we have seen, the marginal product of labor could rise because of an increase in the use of other factors of production, an improvement in technology, or an increase in human capital.

Figure 12.8 Changes in the Demand for and Supply of Labor

Panel (a) shows an increase in demand for labor; the wage rises to W2 and employment rises to L2. A reduction in labor demand, shown in Panel (b), reduces employment and the wage level. An increase in the supply of labor, shown in Panel (c), reduces the wage to W2 and increases employment to L2. Panel (d) shows the effect of a reduction in the supply of labor; wages rise and employment falls.

Clearly, a rising demand for labor has been the dominant trend in the market for U.S. labor through most of the nation’s history. Wages and employment have generally risen as the availability of capital and other factors of production have increased, as technology has advanced, and as human capital has increased. All have increased the productivity of labor, and all have acted to increase wages.

Panel (b) of Figure 12.8 "Changes in the Demand for and Supply of Labor" shows a reduction in the demand for labor to D2. Wages and employment both fall. Given that the demand for labor in the aggregate is generally increasing, reduced labor demand is most often found in specific labor markets. For example, a slump in construction activity in a particular community can lower the demand for construction workers. Technological changes can reduce as well as increase demand. The Case in Point on wages and technology suggests that technological changes since the late 1970s have tended to reduce the demand for workers with only a high school education while increasing the demand for those with college degrees.

Panel (c) of Figure 12.8 "Changes in the Demand for and Supply of Labor" shows the impact of an increase in the supply of labor. The supply curve shifts to S2, pushing employment to L2 and cutting the wage to W2. For labor markets as a whole, such a supply increase could occur because of an increase in population or an increase in the amount of work people are willing to do. For individual labor markets, supply will increase as people move into a particular market.

Just as the demand for labor has increased throughout much of the history of the United States, so has the supply of labor. Population has risen both through immigration and through natural increases. Such increases tend, all other determinants of wages unchanged, to reduce wages. The fact that wages have tended to rise suggests that demand has, in general, increased more rapidly than supply. Still, the more supply rises, the smaller the increase in wages will be, even if demand is rising.

Finally, Panel (d) of Figure 12.8 "Changes in the Demand for and Supply of Labor" shows the impact of a reduction in labor supply. One dramatic example of a drop in the labor supply was caused by a reduction in population after the outbreak of bubonic plague in Europe in 1348—the so-called Black Death. The plague killed about one-third of the people of Europe within a few years, shifting the supply curve for labor sharply to the left. Wages doubled during the period.Carlo M. Cipolla, Before the Industrial Revolution: European Society and Economy, 1000–1700, 2nd ed. (New York: Norton, 1980), pp. 200–202. The doubling in wages was a doubling in real terms, meaning that the purchasing power of an average worker’s wage doubled.

The fact that a reduction in the supply of labor tends to increase wages explains efforts by some employee groups to reduce labor supply. Members of certain professions have successfully promoted strict licensing requirements to limit the number of people who can enter the profession—U.S. physicians have been particularly successful in this effort. Unions often seek restrictions in immigration in an effort to reduce the supply of labor and thereby boost wages.

Competitive Labor Markets and the Minimum Wage

The Case in Point on technology and the wage gap points to an important social problem. Changes in technology boost the demand for highly educated workers. In turn, the resulting wage premium for more highly educated workers is a signal that encourages people to acquire more education. The market is an extremely powerful mechanism for moving resources to the areas of highest demand. At the same time, however, changes in technology seem to be leaving less educated workers behind. What will happen to people who lack the opportunity to develop the skills that the market values highly or who are unable to do so?

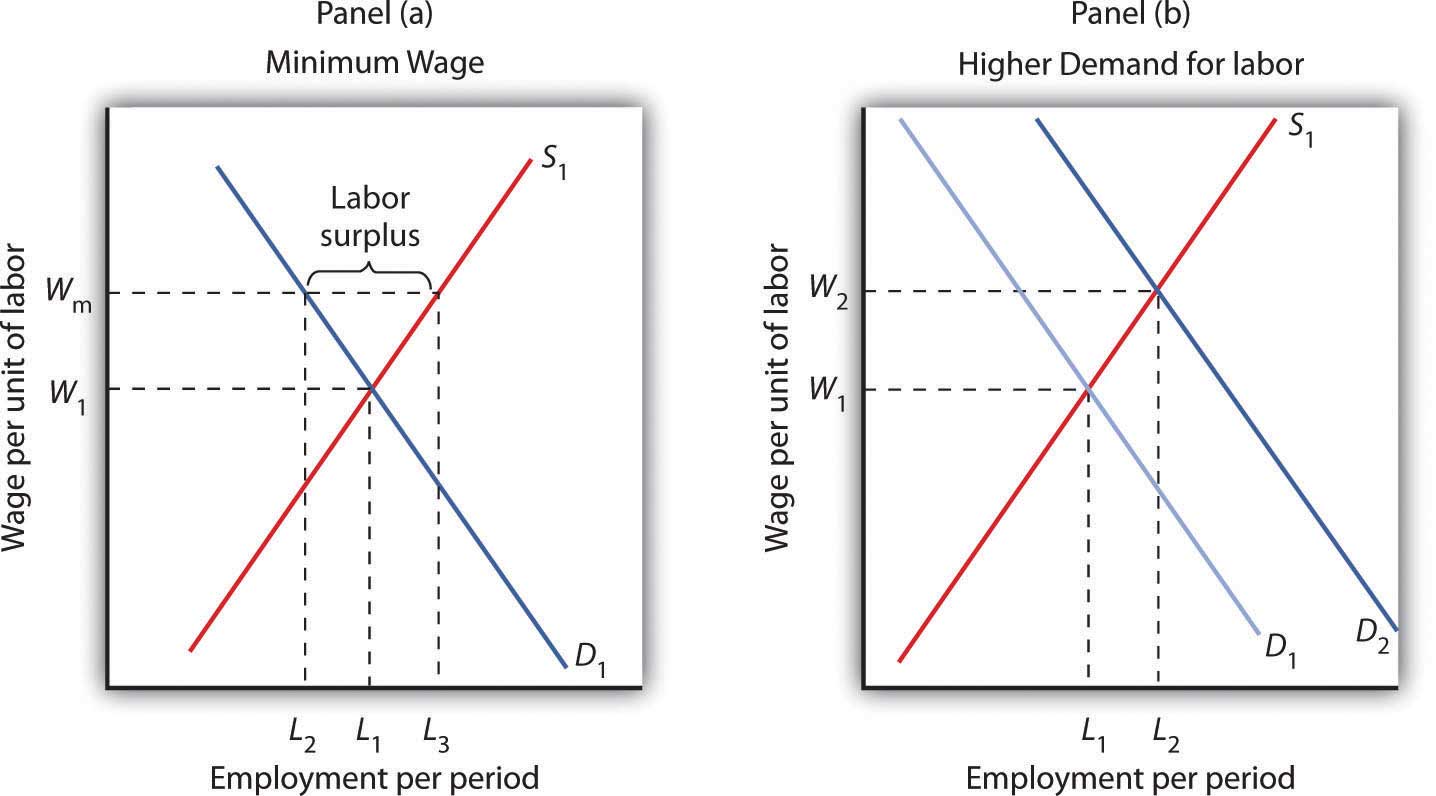

In order to raise wages of workers whose wages are relatively low, governments around the world have imposed minimum wages. A minimum wage works like other price floors. The impact of a minimum wage is shown in Panel (a) of Figure 12.9 "Alternative Responses to Low Wages". Suppose the current equilibrium wage of unskilled workers is W1, determined by the intersection of the demand and supply curves of these workers. The government determines that this wage is too low and orders that it be increased to Wm, a minimum wage. This strategy reduces employment from L1 to L2, but it raises the incomes of those who continue to work. The higher wage also increases the quantity of labor supplied to L3. The gap between the quantity of labor supplied and the quantity demanded, L3 − L2, is a surplus—a surplus that increases unemployment.

Figure 12.9 Alternative Responses to Low Wages

Government can respond to a low wage by imposing a minimum wage of Wm in Panel (a). This increases the quantity of labor supplied and reduces the quantity demanded. It does, however, increase the income of those who keep their jobs. Another way the government can boost wages is by raising the demand for labor in Panel (b). Both wages and employment rise.

Some economists oppose increases in the minimum wage on grounds that such increases boost unemployment. Other economists argue that the demand for unskilled labor is relatively inelastic, so a higher minimum wage boosts the incomes of unskilled workers as a group. That gain, they say, justifies the policy, even if it increases unemployment.

An alternative approach to imposing a legal minimum is to try to boost the demand for labor. Such an approach is illustrated in Panel (b). An increase in demand to D2 pushes the wage to W2 and at the same time increases employment to L2. Public sector training programs that seek to increase human capital are examples of this policy.

Still another alternative is to subsidize the wages of workers whose incomes fall below a certain level. Providing government subsidies—either to employers who agree to hire unskilled workers or to workers themselves in the form of transfer payments—enables people who lack the skills—and the ability to acquire the skills—needed to earn a higher wage to earn more without the loss of jobs implied by a higher minimum wage. Such programs can be costly. They also reduce the incentive for low-skilled workers to develop the skills that are in greater demand in the marketplace.

Key Takeaways

- Wages in a competitive market are determined by demand and supply.

- An increase in demand or a reduction in supply will increase the equilibrium wage. A reduction in demand or an increase in supply will reduce the equilibrium wage.

- The government may respond to low wages for some workers by imposing the minimum wage, by attempting to increase the demand for those workers, or by subsidizing the wages of workers whose incomes fall below a certain level.

Try It!

Assuming that the market for construction workers is perfectly competitive, illustrate graphically how each of the following would affect the demand or supply for construction workers. What would be the impact on wages and on the number of construction workers employed?

- The demand for new housing increases as more people move into the community.

- Changes in societal attitudes lead to more women wanting to work in construction.

- Improved training makes construction workers more productive.

- New technology allows much of the framing used in housing construction to be built by robots at a factory and then shipped to construction sites.

Case in Point: Technology and the Wage Gap

© 2010 Jupiterimages Corporation

Economist Daron Acemoglu’s research begins by noting that the college premium, defined as the average wages of college graduates relative to that of high school graduates, rose 25% between 1979 and 1995 in the United States. Also, during essentially the same period, wage inequality rose. Whereas in the early 1970s, a person in the 90th percentile of the wage distribution earned 266% more than a person in the 10th percentile earned, 25 years later the gap had increased to 366%. The consensus view maintains that the increase in the college premium and in wage inequality stem primarily from skill-biased technological change. Skill-biased technological change means that, in general, newly developed technologies have favored the hiring of workers with better education and more skills.

But while technological advances may increase the demand for skilled workers, the opposite can also occur. For example, the rise of factories, assembly lines, and interchangeable parts in the nineteenth century reduced the demand for skilled artisans such as weavers and watchmakers. So, the twentieth century skill-bias of technological change leads researchers to ask why recent technological change has taken the form it has.

Acemoglu’s answer is that, at least in part, the character of technological change itself constitutes a response to profit incentives:

The early nineteenth century was characterized by skill-replacing developments because the increased supply of unskilled workers in the English cities (resulting from migration from rural areas and from Ireland) made the introduction of these technologies profitable. In contrast, the twentieth century has been characterized by skill-biased technical change because the rapid increase in the supply of skilled workers has induced the development of skill-complementary technologies. (p. 9)

In general, technological change in this model is endogenous—that is, its character is shaped by any incentives that firms face.

Of course, an increase in the supply of skilled labor, as has been occurring relentlessly in the United States over the past century, would, other things unchanged, lead to a fall in the wage premium. Acemoglu and others argue that the increase in the demand for skilled labor has simply outpaced the increase in supply.

But this also begs the why question. Acemoglu’s answer again relies on the profit motive:

The development of skill-biased technologies will be more profitable when they have a larger market size—i.e., when there are more skilled workers. Therefore, the equilibrium degree of skill bias could be an increasing function of the relative supply of skilled workers. An increase in the supply of skills will then lead to skill-biased technological change. Furthermore, acceleration in the supply of skills can lead to acceleration in the demand for skill. (p. 37)

It follows from this line of reasoning that the rapid increase in the supply of college-educated workers led to more skill-biased technologies that in turn led to a higher college premium.

While these ideas explain the college premium, they do not address why the real wages of low-skilled workers have fallen in recent decades. Popular explanations include the decreased role of labor unions, the increased role of international trade, and immigration. Many studies, though, have concluded that the direct impacts of these factors have been limited. For example, in both the United States and United Kingdom, rising wage inequality preceded the decline of labor unions. Concerning the impact of trade and immigration on inequality, most research concludes that changes in these areas have not been large enough, despite how much they figure into the public’s imagination. For example, according to economists Aaron Steelman and John Weinberg, immigration accounted for a 2 million person increase in the labor force in the 1970s, when the baby boom and increased labor force participation of women added 20 million workers. During the 1980s, immigration was relatively high but still only accounted for a one percentage point increase, from 7 to 8%, in immigrant share of the total labor supply. While Acemoglu accepts those conclusions, he argues that labor market institutions and trade may have interacted with technological change to magnify technological change’s direct effect on inequality. For example, skill-biased technological change makes wage compression that unions tend to advocate more costly for skilled workers and thus weakens the “coalition between skilled and unskilled work that maintains unions” (p. 52). Likewise, trade expansion with less developed countries may have led to more skill-biased technological change than otherwise would have occurred.

Acemoglu recognizes that more research is needed to determine whether these indirect effects are operating and, if they are, the sizes of these effects, but looking at how technological change responds to economic conditions may begin to solve some heretofore puzzling aspects of recent labor market changes.

What is to be done, if anything, about widening inequality? Steelman and Weinberg argue, “First, do no harm.” They state,

Increased trade with LDCs and immigration from abroad likely have had little effect on wage inequality, while almost certainly adding to the strength and vitality of the American economy. Efforts to slow the growth of foreign goods or labor coming to our shores would be costly to Americans as a whole, as well as to those people who seem to be hurt by globalization at present. (p. 11)

However, they do suggest that policies to promote acquisition of skills, especially in early education where the return seems especially high, may be useful.

Sources: Daron Acemoglu, “Technical Change, Inequality, and the Labor Market,” Journal of Economic Literature 40:1 (March 2002): 7–73; Aaron Steelman and John A. Weinberg, “What’s Driving Wage Inequality,” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Quarterly 91:3 (Summer 2005): 1–17.

Answers to Try It! Problems

- An increase in the demand for new housing would shift the demand curve for construction workers to the right, as shown in Figure 12.8 "Changes in the Demand for and Supply of Labor", Panel (a). Both the wage rate and the employment in construction rise.

- A larger number of women wanting to work in construction means an increase in labor supply, as shown in Figure 12.8 "Changes in the Demand for and Supply of Labor", Panel (c). An increase in the supply of labor reduces the wage rate and increases employment.

- Improved training would increase the marginal revenue product of construction workers and hence increase demand for them. Wages and employment would rise, as shown in Figure 12.8 "Changes in the Demand for and Supply of Labor", Panel (a).

- The robots are likely to serve as a substitute for labor. That will reduce demand, wages, and employment of construction workers, as shown in Panel (b).