This is “Media Mix: Convergence”, section 1.4 from the book Mass Communication, Media, and Culture (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

1.4 Media Mix: Convergence

Learning Objectives

- Define convergence and discuss examples of it in contemporary life.

- Name the five types of convergence identified by Henry Jenkins.

- Examine how convergence is affecting culture and society.

Each cultural era is marked by changes in technology. What happens to the “old” technology? When radio was invented, people predicted the end of newspapers. When television was invented, people predicted the end of radio and film. It’s important to keep in mind that the implementation of new technologies does not mean that the old ones simply vanish into dusty museums. Today’s media consumers still read newspapers, listen to radio, watch television, and get immersed in movies. The difference is that it’s now possible to do all those things and do all those things through one device—be it a personal computer or a smartphone—and through the medium of the Internet. Such actions are enabled by media convergenceThe process by which previously distinct technologies come to share content, tasks, and resources., the process by which previously distinct technologies come to share content, tasks and resources. A cell phone that also takes pictures and video is an example of the convergence of digital photography, digital video, and cellular telephone technologies. A news story that originally appeared in a newspaper and now is published on a website or pushed on a mobile phone is another example of convergence.

Kinds of Convergence

Convergence isn’t just limited to technology. Media theorist Henry Jenkins has devoted a lot of time to thinking about convergence. He argues that convergence isn’t an end result but instead a process that changes how media is both consumed and produced. Jenkins breaks convergence down into five categories:

- Economic convergence is the horizontal and vertical integration of the entertainment industry, in which a single company has interests across and within many kinds of media. For example, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation owns numerous newspapers (The New York Post, The Wall Street Journal) but is also involved in book publishing (HarperCollins), sports (the Colorado Rockies), broadcast television (Fox), cable television (FX, National Geographic Channel), film (20th Century Fox), Internet (Facebook), and many others.

- Organic convergence is what happens when someone is watching television while chatting online and also listening to music—such multitasking seems like a natural outcome in a diverse media world.

-

Cultural convergence has several different aspects. One important component is stories flowing across several kinds of media platforms—for example, novels that become television series (Dexter or Friday Night Lights); radio dramas that become comic strips (The Shadow); even amusement park rides that become film franchises (Pirates of the Caribbean). The character Harry Potter exists in books, films, toys, amusement park rides, and candy bars. Another aspect of cultural convergence is participatory cultureA culture in which media consumers are able to annotate, comment on, remix, and otherwise respond to culture.—that is, the way media consumers are able to annotate, comment on, remix, and otherwise talk back to culture in unprecedented ways.

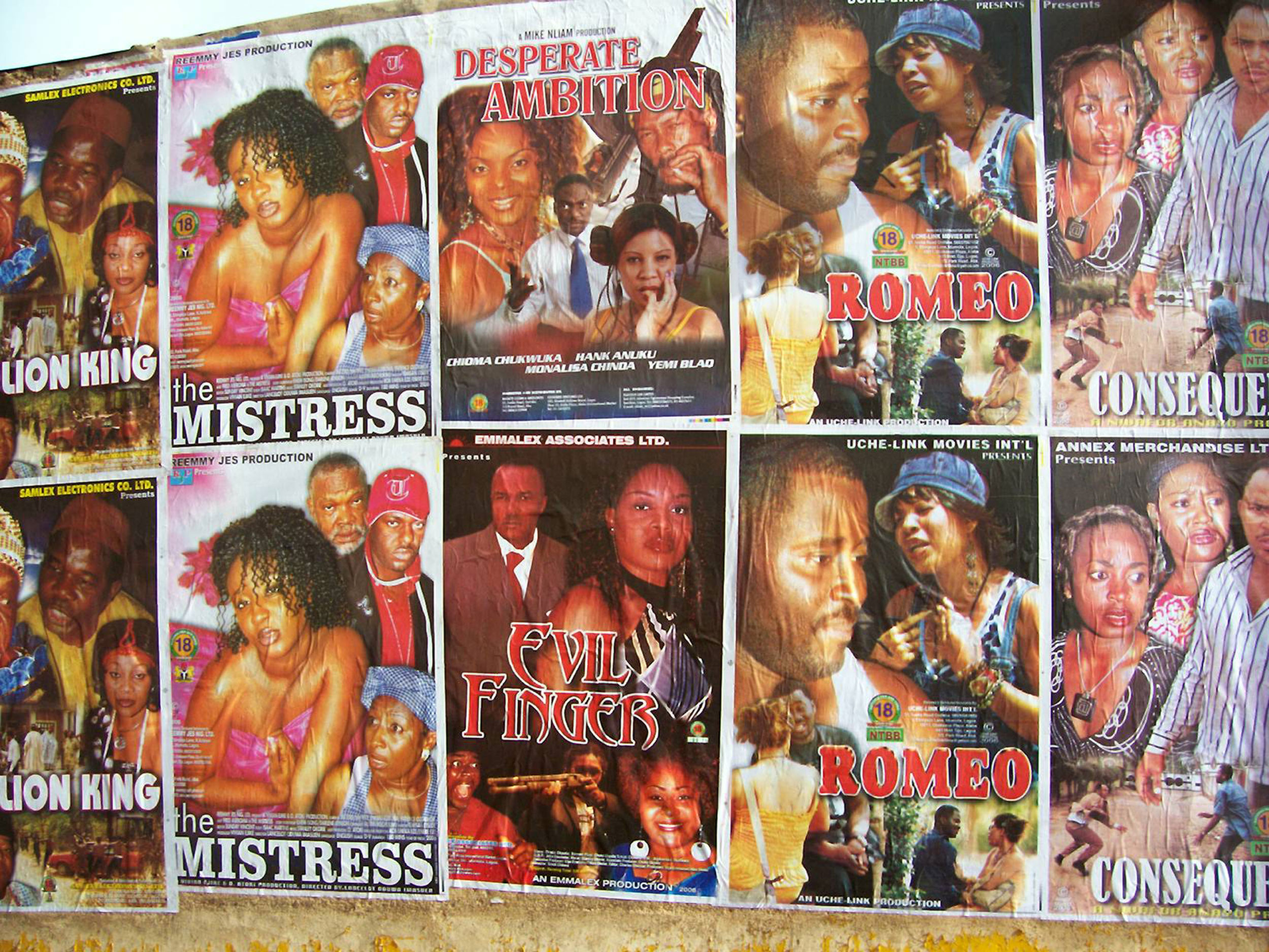

Figure 1.5

Nigeria’s Nollywood produces more films annually than any other country besides India.

- Global convergence is the process of geographically distant cultures influencing one another despite the oceans and mountains that may physically separate them. Nigeria’s “Nollywood” cinema takes its cues from India’s Bollywood, which of course stemmed from Hollywood; old Tom and Jerry cartoons and newer Oprah shows are popular on Arab satellite television channels; successful American horror movies like The Ring and The Grudge are remakes of Japanese hits; the hit television show, “American Idol” was a remake of a British show. The advantage of global convergence is worldwide access to a wealth of cultural influence. Its downside, some critics posit, is the threat of cultural imperialismThe theory that certain cultures are attracted or pressured into shaping social institutions to correspond to, or even promote, the values and structures of a different culture, one that generally wields more economic power., defined by Herbert Schiller as the way that developing countries are “attracted, pressured, forced, and sometimes bribed into shaping social institutions to correspond to, or even promote, the values and structures of the dominating centre of the system.” That is, less powerful nations lose their cultural traditions as more powerful nations spread their culture through their media and other forms. Cultural imperialism can be a formal policy or can happen more subtly, as with the spread of outside influence through television, movies, and other cultural projects.

- Technological convergence is the merging of technologies. When more and more different kinds of media are transformed into digital content, as Jenkins notes, “we expand the potential relationships between them and enable them to flow across platforms.”Henry Jenkins, “Convergence? I Diverge,” Technology Review, June 2001, p. 93.

Effects of Convergence

Jenkins’ concept of “organic convergence”—particularly, multitasking—is perhaps most evident in your own lives. To many who grew up in a world dominated by so-called old media, there is nothing organic about today’s mediated world. As a New York Times editorial sniffed, “Few objects on the planet are farther removed from nature—less, say, like a rock or an insect—than a glass and stainless steel smartphone.”Editorial, “The Half-Life of Phones,” The New York Times, Week in Review section, June 18, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/20/opinion/20sun4.html?_r=1 (accessed July 15, 2010). But modern American culture is plugged in as never before, and many students today have never known a world where the Internet didn’t exist. Such a cultural sea change causes a significant generation gap between those who grew up with new media and those who didn’t.

A 2010 study by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that Americans aged 8 to 18 spend more than 7.5 hours with electronic devices each day—and, thanks to multitasking, they’re able to pack an average of 11 hours of media content into that 7.5 hours.Tamar Lewin, “If Your Kids Are Awake, They’re Probably Online,” The New York Times, Education section, January 20, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/20/education/20wired.html (accessed July 15, 2010). These statistics highlight some of the aspects of the new digital model of media consumption: participation and multitasking. Today’s teenagers aren’t passively sitting in front of screens, quietly absorbing information. Instead, they are sending text messages to friends, linking news articles on Facebook, commenting on YouTube videos, writing reviews of television episodes to post online, and generally engaging with the culture they consume. Convergence has also made multitasking much easier, as many devices allow users to surf the Internet, listen to music, watch videos, play games, and reply to emails and texts on the same machine.

However, this multitasking is still quite new and we do not know how media convergence and immersion are shaping culture, people, and individual brains. In his 2005 book Everything Bad Is Good for You, Steven Johnson argues that today’s television and video games are mentally stimulating, in that they pose a cognitive challenge and invite active engagement and problem-solving. Poking fun at alarmists who see every new technology as making children more stupid, Johnson jokingly cautions readers against the dangers of book reading: it “chronically understimulates the senses” and is “tragically isolating.” Even worse, books “follow a fixed linear path. You can’t control their narratives in any fashion—you simply sit back and have the story dictated to you.…This risks instilling a general passivity in our children, making them feel as though they’re powerless to change their circumstances. Reading is not an active, participatory process; it’s a submissive one.”Steven Johnson, Everything Bad Is Good for You (Riverhead, NY: Riverhead Books, 2005).

A 2010 book by Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains is more pessimistic. Carr worries that the vast array of interlinked information available through the Internet is eroding attention spans and making contemporary minds distracted and less capable of deep, thoughtful engagement with complex ideas and arguments. He mourns the change in his own reading habits. “Once I was a scuba diver in a sea of words,” Carr reflects ruefully. “Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.” Carr cites neuroscience studies showing that when people try to do two things at once, they give less attention to each and perform the tasks less carefully. In other words, multitasking makes us do a greater number of things poorly. Whatever the ultimate cognitive, social, or technological results, though, convergence is changing the way we relate to media today.

Video Killed the Radio Star: Convergence Kills Off Obsolete Technology—Or Does It?

When was the last time you used a rotary phone? How about a payphone on a street? Or a library’s card catalog? When you need brief, factual information, when was the last time you reached for a handy volume of Encyclopedia Britannica? Odds are, it’s been a while. Maybe never. All of these habits, formerly common parts of daily life, have been rendered essentially obsolete through the progression of convergence.

But convergence hasn’t erased old technologies; instead, it may have just altered the way we use them. Take cassette tapes and Polaroid film, for example. The underground music tastemaker Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth recently claimed that he only listens to music on cassette. Polaroid Corporation, creators of the once-popular instant film cameras, was driven out of business by digital photography in 2008, only to be revived two years later—with pop star Lady Gaga as the brand’s creative director. Several iPhone apps promise to apply effects to photos to make them look more like Polaroids.

Cassettes, Polaroids, and other seemingly obsolete technologies have been able to thrive—albeit in niche markets—both despite and because of Internet culture. Instead of being slick and digitized, cassette tapes and Polaroid photos are physical objects that are made more accessible and more human, according to enthusiasts, because of their flaws. “I think there’s a group of people—fans and artists alike—out there to whom music is more than just a file on your computer, more than just a folder of mp3s,” says Brad Rose, founder of a Tulsa-based cassette label. The distinctive Polaroid look—caused by uneven color saturation, under- or over-development, or just daily atmospheric effects on the developing photograph—is emphatically analog. In an age of high resolution, portable printers, and camera phones, the Polaroid’s appeal has something to do with ideas of nostalgia and authenticity. Convergence has transformed who uses these media and for what purposes, but it hasn’t run them out of town yet.

Key Takeaways

- Twenty-first century media culture is increasingly marked by convergence, or the coming together of previously distinct technologies, as in a cell phone that also allows users to take video and check email.

-

Media theorist Henry Jenkins identifies the five kinds of convergence as the following:

- Economic convergence, when a single company has interests across many kinds of media.

- Organic convergence is multimedia multitasking, or the “natural” outcome of a diverse media world.

- Cultural convergence, when stories flow across several kinds of media platforms, and when readers or viewers can comment on, alter, or otherwise talk back to culture.

- Global convergence, when geographically distant cultures are able to influence one another.

- Technological convergence, in which different kinds of technology merge. The most extreme example of technological convergence would be the as-yet hypothetical “black box,” one machine that controlled every media function.

- The jury is still out on how these different types of convergence will affect people on an individual and cultural level. Some theorists believe that convergence and new media technologies make people smarter by requiring them to make decisions and interact with the media they’re consuming; others fear that the digital age is giving us access to more information but leaving us shallower.

Exercise

Which argument do you find more compelling, Johnson’s or Carr’s? Make a list of points, examples, and facts that back up the theory that you think best explains the effects of convergence. Alternatively, come up with your own theory of how convergence is changing individual and society as a whole. Stage a mock debate with a member of the class who holds a view different from your own.