This is “Nonlinear Relationships and Graphs without Numbers”, section 1.2 (from appendix 1) from the book Macroeconomics Principles (v. 1.1). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

21.2 Nonlinear Relationships and Graphs without Numbers

Learning Objectives

- Understand nonlinear relationships and how they are illustrated with nonlinear curves.

- Explain how to estimate the slope at any point on a nonlinear curve.

- Explain how graphs without numbers can be used to understand the nature of relationships between two variables.

In this section we will extend our analysis of graphs in two ways: first, we will explore the nature of nonlinear relationships; then we will have a look at graphs drawn without numbers.

Graphs of Nonlinear Relationships

In the graphs we have examined so far, adding a unit to the independent variable on the horizontal axis always has the same effect on the dependent variable on the vertical axis. When we add a passenger riding the ski bus, the ski club’s revenues always rise by the price of a ticket. The cancellation of one more game in the 1998–1999 basketball season would always reduce Shaquille O’Neal’s earnings by $210,000. The slopes of the curves describing the relationships we have been discussing were constant; the relationships were linear.

Many relationships in economics are nonlinear. A nonlinear relationshipRelationship between two variables in which the slope of the curve showing the relationship changes as the value of one of the variables changes. between two variables is one for which the slope of the curve showing the relationship changes as the value of one of the variables changes. A nonlinear curveA curve whose slope changes as the value of one of the variables changes. is a curve whose slope changes as the value of one of the variables changes.

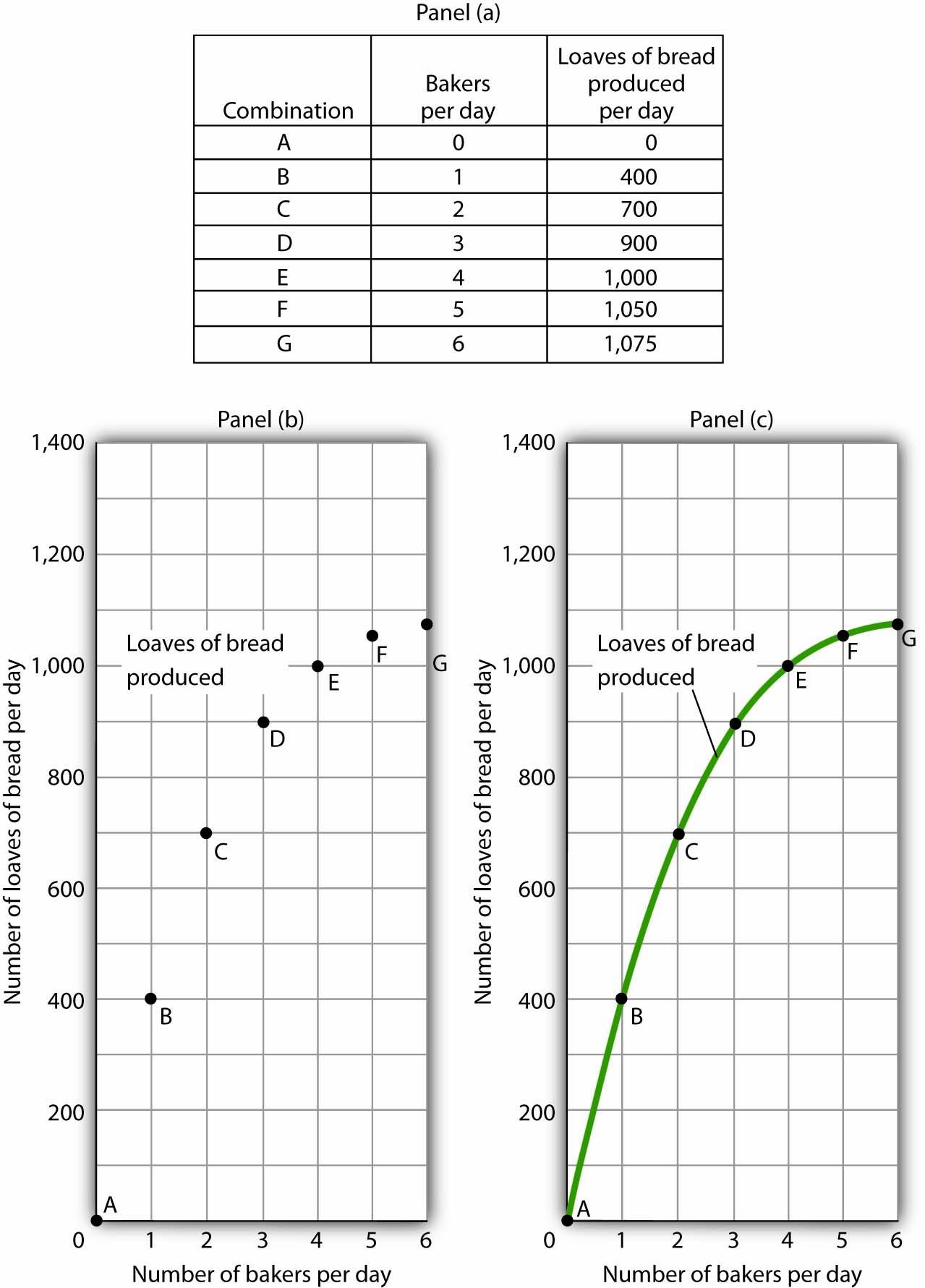

Consider an example. Suppose Felicia Alvarez, the owner of a bakery, has recorded the relationship between her firm’s daily output of bread and the number of bakers she employs. The relationship she has recorded is given in the table in Panel (a) of Figure 21.12 "A Nonlinear Curve". The corresponding points are plotted in Panel (b). Clearly, we cannot draw a straight line through these points. Instead, we shall have to draw a nonlinear curve like the one shown in Panel (c).

Figure 21.12 A Nonlinear Curve

The table in Panel (a) shows the relationship between the number of bakers Felicia Alvarez employs per day and the number of loaves of bread produced per day. This information is plotted in Panel (b). This is a nonlinear relationship; the curve connecting these points in Panel (c) (Loaves of bread produced) has a changing slope.

Inspecting the curve for loaves of bread produced, we see that it is upward sloping, suggesting a positive relationship between the number of bakers and the output of bread. But we also see that the curve becomes flatter as we travel up and to the right along it; it is nonlinear and describes a nonlinear relationship.

How can we estimate the slope of a nonlinear curve? After all, the slope of such a curve changes as we travel along it. We can deal with this problem in two ways. One is to consider two points on the curve and to compute the slope between those two points. Another is to compute the slope of the curve at a single point.

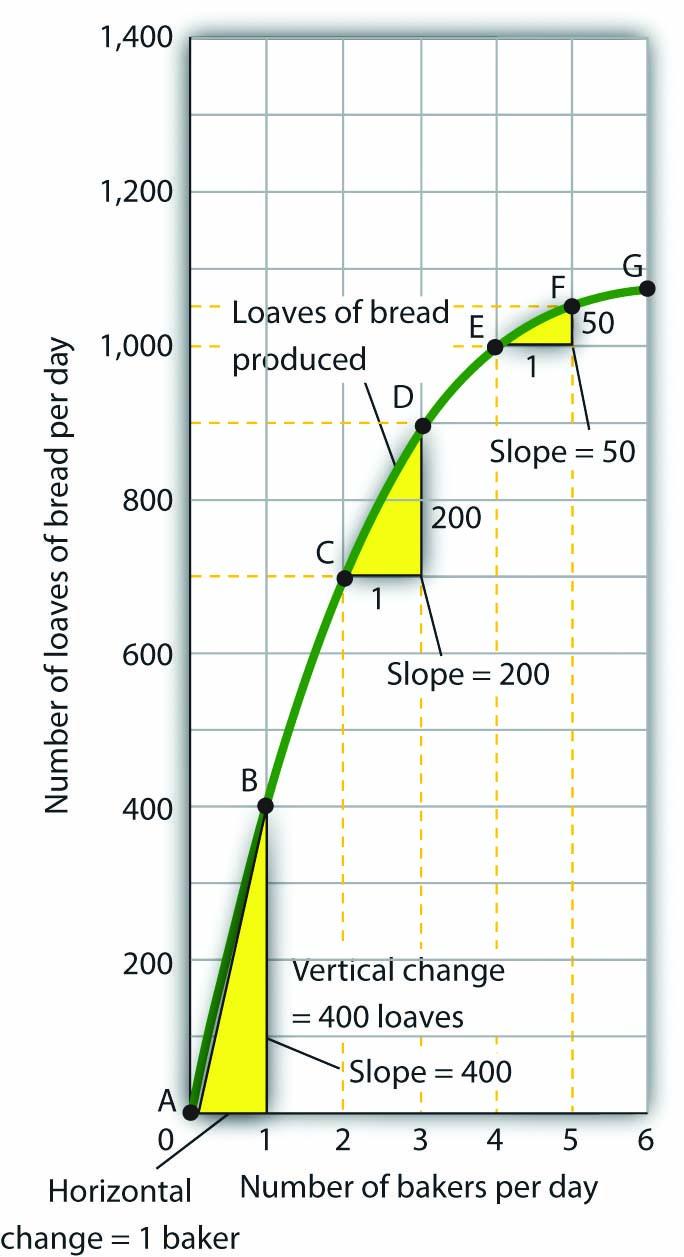

When we compute the slope of a curve between two points, we are really computing the slope of a straight line drawn between those two points. In Figure 21.13 "Estimating Slopes for a Nonlinear Curve", we have computed slopes between pairs of points A and B, C and D, and E and F on our curve for loaves of bread produced. These slopes equal 400 loaves/baker, 200 loaves/baker, and 50 loaves/baker, respectively. They are the slopes of the dashed-line segments shown. These dashed segments lie close to the curve, but they clearly are not on the curve. After all, the dashed segments are straight lines. Our curve relating the number of bakers to daily bread production is not a straight line; the relationship between the bakery’s daily output of bread and the number of bakers is nonlinear.

Figure 21.13 Estimating Slopes for a Nonlinear Curve

We can estimate the slope of a nonlinear curve between two points. Here, slopes are computed between points A and B, C and D, and E and F. When we compute the slope of a nonlinear curve between two points, we are computing the slope of a straight line between those two points. Here the lines whose slopes are computed are the dashed lines between the pairs of points.

Every point on a nonlinear curve has a different slope. To get a precise measure of the slope of such a curve, we need to consider its slope at a single point. To do that, we draw a line tangent to the curve at that point. A tangent lineA straight line that touches, but does not intersect, a nonlinear curve at only one point. is a straight line that touches, but does not intersect, a nonlinear curve at only one point. The slope of a tangent line equals the slope of the curve at the point at which the tangent line touches the curve.

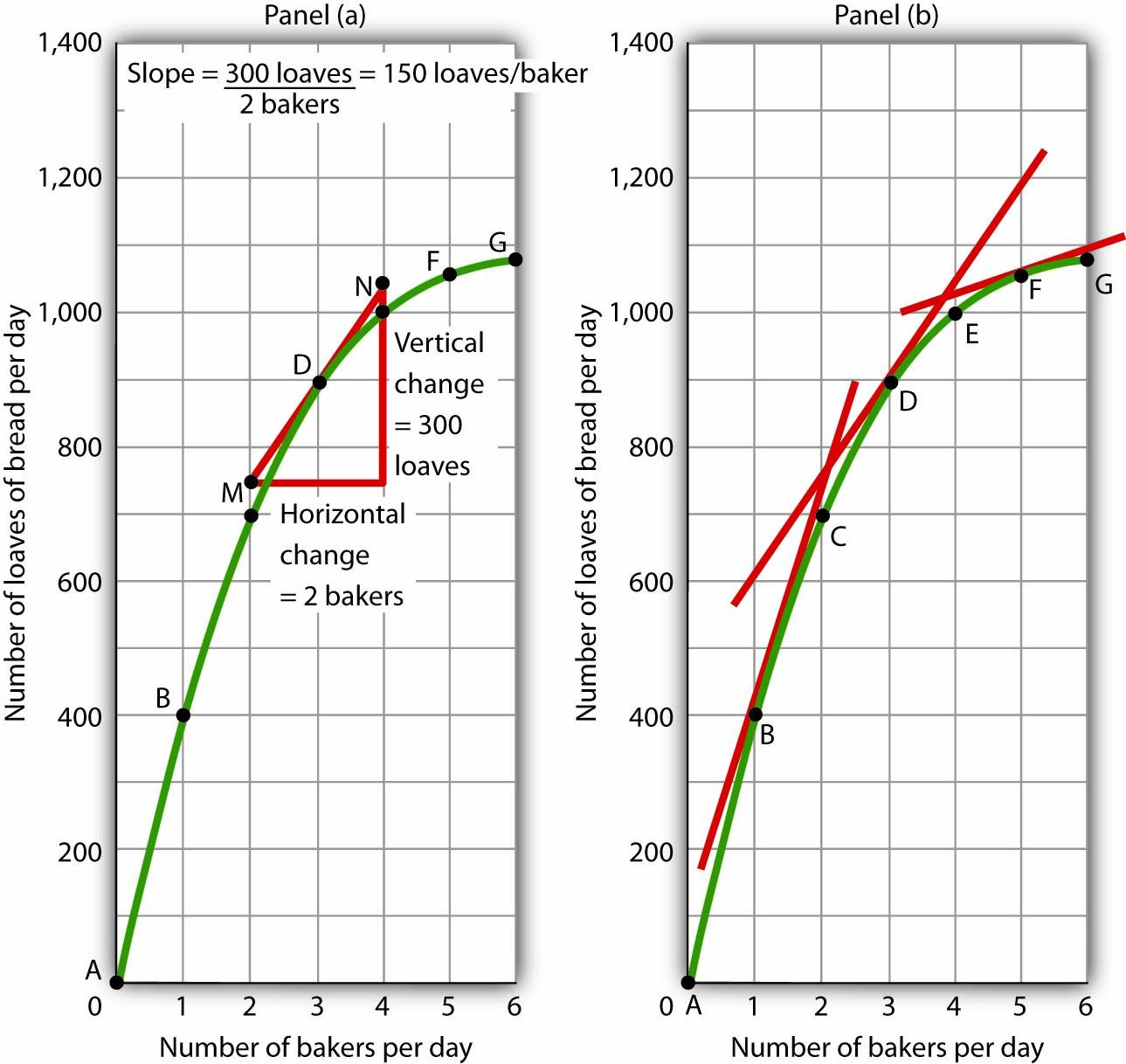

Consider point D in Panel (a) of Figure 21.14 "Tangent Lines and the Slopes of Nonlinear Curves". We have drawn a tangent line that just touches the curve showing bread production at this point. It passes through points labeled M and N. The vertical change between these points equals 300 loaves of bread; the horizontal change equals two bakers. The slope of the tangent line equals 150 loaves of bread/baker (300 loaves/2 bakers). The slope of our bread production curve at point D equals the slope of the line tangent to the curve at this point. In Panel (b), we have sketched lines tangent to the curve for loaves of bread produced at points B, D, and F. Notice that these tangent lines get successively flatter, suggesting again that the slope of the curve is falling as we travel up and to the right along it.

Figure 21.14 Tangent Lines and the Slopes of Nonlinear Curves

Because the slope of a nonlinear curve is different at every point on the curve, the precise way to compute slope is to draw a tangent line; the slope of the tangent line equals the slope of the curve at the point the tangent line touches the curve. In Panel (a), the slope of the tangent line is computed for us: it equals 150 loaves/baker. Generally, we will not have the information to compute slopes of tangent lines. We will use them as in Panel (b), to observe what happens to the slope of a nonlinear curve as we travel along it. We see here that the slope falls (the tangent lines become flatter) as the number of bakers rises.

Notice that we have not been given the information we need to compute the slopes of the tangent lines that touch the curve for loaves of bread produced at points B and F. In this text, we will not have occasion to compute the slopes of tangent lines. Either they will be given or we will use them as we did here—to see what is happening to the slopes of nonlinear curves.

In the case of our curve for loaves of bread produced, the fact that the slope of the curve falls as we increase the number of bakers suggests a phenomenon that plays a central role in both microeconomic and macroeconomic analysis. As we add workers (in this case bakers), output (in this case loaves of bread) rises, but by smaller and smaller amounts. Another way to describe the relationship between the number of workers and the quantity of bread produced is to say that as the number of workers increases, the output increases at a decreasing rate. In Panel (b) of Figure 21.14 "Tangent Lines and the Slopes of Nonlinear Curves" we express this idea with a graph, and we can gain this understanding by looking at the tangent lines, even though we do not have specific numbers. Indeed, much of our work with graphs will not require numbers at all.

We turn next to look at how we can use graphs to express ideas even when we do not have specific numbers.

Graphs Without Numbers

We know that a positive relationship between two variables can be shown with an upward-sloping curve in a graph. A negative or inverse relationship can be shown with a downward-sloping curve. Some relationships are linear and some are nonlinear. We illustrate a linear relationship with a curve whose slope is constant; a nonlinear relationship is illustrated with a curve whose slope changes. Using these basic ideas, we can illustrate hypotheses graphically even in cases in which we do not have numbers with which to locate specific points.

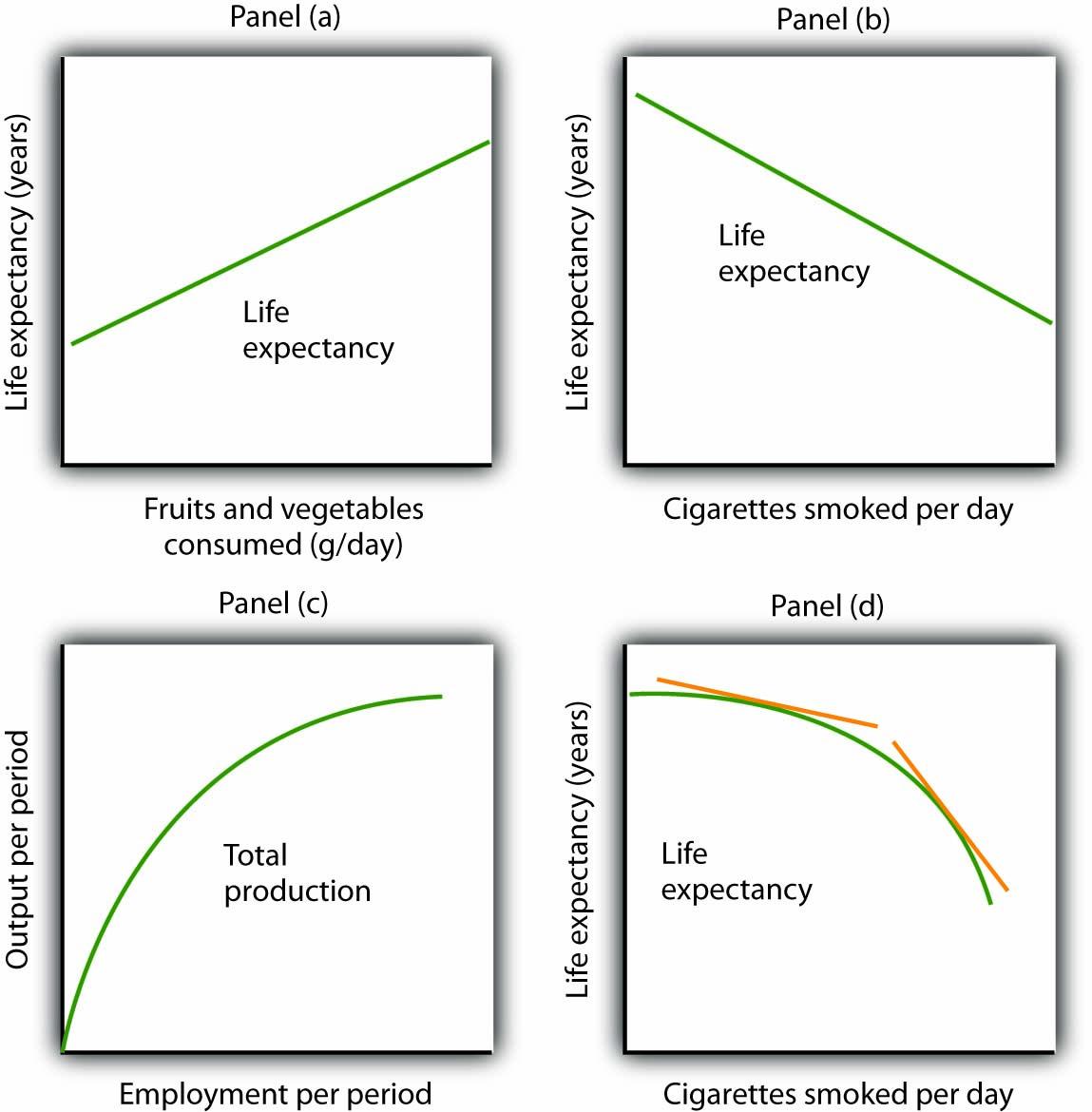

Consider first a hypothesis suggested by recent medical research: eating more fruits and vegetables each day increases life expectancy. We can show this idea graphically. Daily fruit and vegetable consumption (measured, say, in grams per day) is the independent variable; life expectancy (measured in years) is the dependent variable. Panel (a) of Figure 21.15 "Graphs Without Numbers" shows the hypothesis, which suggests a positive relationship between the two variables. Notice the vertical intercept on the curve we have drawn; it implies that even people who eat no fruit or vegetables can expect to live at least a while!

Figure 21.15 Graphs Without Numbers

We often use graphs without numbers to suggest the nature of relationships between variables. The graphs in the four panels correspond to the relationships described in the text.

Panel (b) illustrates another hypothesis we hear often: smoking cigarettes reduces life expectancy. Here the number of cigarettes smoked per day is the independent variable; life expectancy is the dependent variable. The hypothesis suggests a negative relationship. Hence, we have a downward-sloping curve.

Now consider a general form of the hypothesis suggested by the example of Felicia Alvarez’s bakery: increasing employment each period increases output each period, but by smaller and smaller amounts. As we saw in Figure 21.12 "A Nonlinear Curve", this hypothesis suggests a positive, nonlinear relationship. We have drawn a curve in Panel (c) of Figure 21.15 "Graphs Without Numbers" that looks very much like the curve for bread production in Figure 21.14 "Tangent Lines and the Slopes of Nonlinear Curves". It is upward sloping, and its slope diminishes as employment rises.

Finally, consider a refined version of our smoking hypothesis. Suppose we assert that smoking cigarettes does reduce life expectancy and that increasing the number of cigarettes smoked per day reduces life expectancy by a larger and larger amount. Panel (d) shows this case. Again, our life expectancy curve slopes downward. But now it suggests that smoking only a few cigarettes per day reduces life expectancy only a little but that life expectancy falls by more and more as the number of cigarettes smoked per day increases.

We have sketched lines tangent to the curve in Panel (d). The slopes of these tangent lines are negative, suggesting the negative relationship between smoking and life expectancy. They also get steeper as the number of cigarettes smoked per day rises. Whether a curve is linear or nonlinear, a steeper curve is one for which the absolute value of the slope rises as the value of the variable on the horizontal axis rises. When we speak of the absolute value of a negative number such as −4, we ignore the minus sign and simply say that the absolute value is 4. The absolute value of −8, for example, is greater than the absolute value of −4, and a curve with a slope of −8 is steeper than a curve whose slope is −4.

Thus far our work has focused on graphs that show a relationship between variables. We turn finally to an examination of graphs and charts that show values of one or more variables, either over a period of time or at a single point in time.

Key Takeaways

- The slope of a nonlinear curve changes as the value of one of the variables in the relationship shown by the curve changes.

- A nonlinear curve may show a positive or a negative relationship.

- The slope of a curve showing a nonlinear relationship may be estimated by computing the slope between two points on the curve. The slope at any point on such a curve equals the slope of a line drawn tangent to the curve at that point.

- We can illustrate hypotheses about the relationship between two variables graphically, even if we are not given numbers for the relationships. We need only draw and label the axes and then draw a curve consistent with the hypothesis.

Try It!

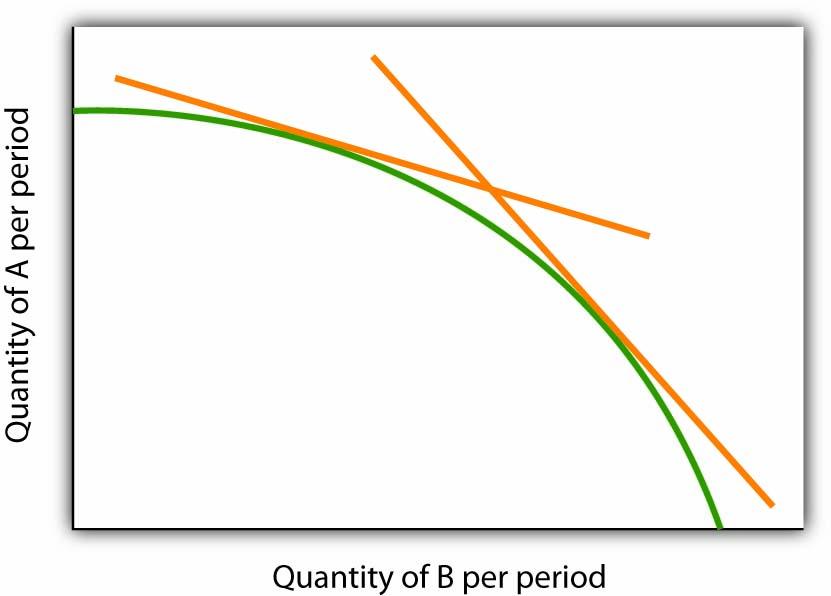

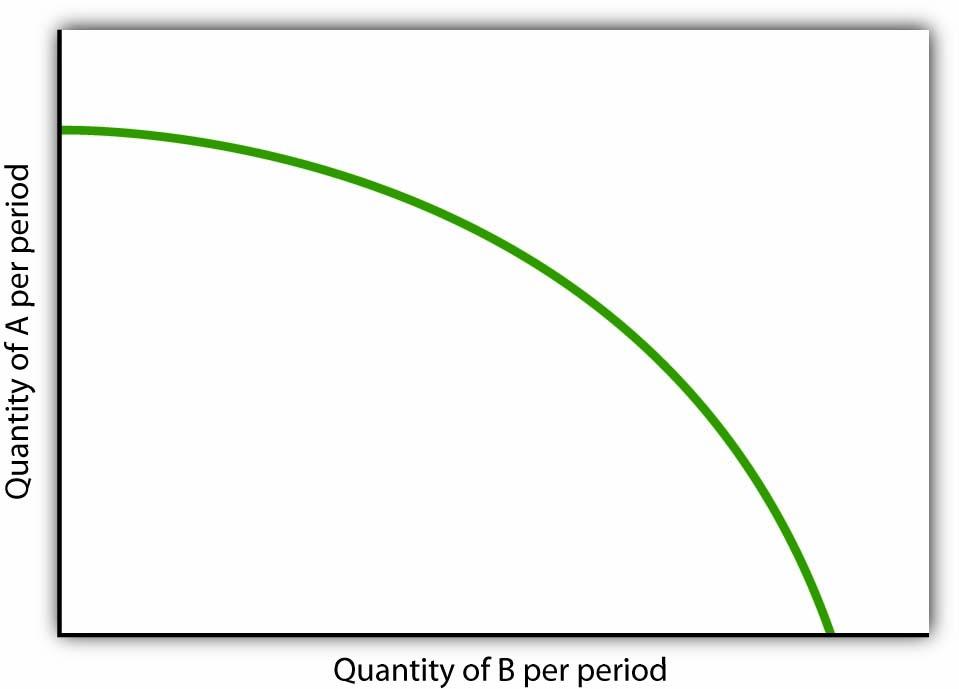

Consider the following curve drawn to show the relationship between two variables, A and B (we will be using a curve like this one in the next chapter). Explain whether the relationship between the two variables is positive or negative, linear or nonlinear. Sketch two lines tangent to the curve at different points on the curve, and explain what is happening to the slope of the curve.

Figure 21.16

Answer to Try It!

The relationship between variable A shown on the vertical axis and variable B shown on the horizontal axis is negative. This is sometimes referred to as an inverse relationship. Variables that give a straight line with a constant slope are said to have a linear relationship. In this case, however, the relationship is nonlinear. The slope changes all along the curve. In this case the slope becomes steeper as we move downward to the right along the curve, as shown by the two tangent lines that have been drawn. As the quantity of B increases, the quantity of A decreases at an increasing rate.

Figure 21.17