This is “Fixtures”, section 9.3 from the book Legal Aspects of Property, Estate Planning, and Insurance (v. 1.0). For details on it (including licensing), click here.

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. To download a .zip file containing this book to use offline, simply click here.

9.3 Fixtures

Learning Objective

- Know the three tests for when personal property becomes a fixture and thus becomes real property.

Definition

A fixtureAn object that was once personal property that has become so affixed to land or structures that it is legally a part of the real property. is an object that was once personal property but that has become so affixed to land or structures that it is considered legally a part of the real property. For example, a stove bolted to the floor of a kitchen and connected to the gas lines is usually considered a fixture, either in a contract for sale, or for testamentary transfer (by will). For tax purposes, fixtures are treated as real property.

Tests

Figure 9.2 Fixture Tests

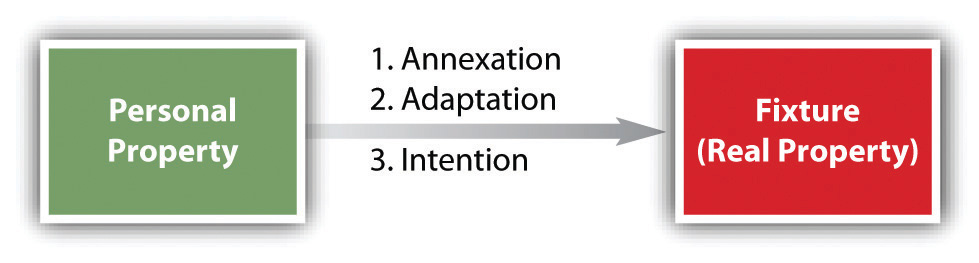

Obviously, no clear line can be drawn between what is and what is not a fixture. In general, the courts look to three tests to determine whether a particular object has become a fixture: annexation, adaptation, and intention (see Figure 9.2 "Fixture Tests").

Annexation

The object must be annexed or affixed to the real property. A door on a house is affixed. Suppose the door is broken and the owner has purchased a new door made to fit, but the house is sold before the new door is installed. Most courts would consider that new door a fixture under a rule of constructive annexation. Sometimes courts have said that an item is a fixture if its removal would damage the real property, but this test is not always followed. Must the object be attached with nails, screws, glue, bolts, or some other physical device? In one case, the court held that a four-ton statue was sufficiently affixed merely by its weight.Snedeker v. Warring, 12 N.Y. 170 (1854).

Adaptation

Another test is whether the object is adapted to the use or enjoyment of the real property. Examples are home furnaces, power equipment in a mill, and computer systems in bank buildings.

Intention

Recent decisions suggest that the controlling test is whether the person who actually annexes the object intends by so doing to make it a permanent part of the real estate. The intention is usually deduced from the circumstances, not from what a person might later say her intention was. If an owner installs a heating system in her house, the law will presume she intended it as a fixture because the installation was intended to benefit the house; she would not be allowed to remove the heating system when she sold the house by claiming that she had not intended to make it a fixture.

Fixture Disputes

Because fixtures have a hybrid nature (once personal property, subsequently real property), they generate a large number of disputes. We have already examined disputes between mortgagees and secured parties (Chapter 16 "Secured Transactions and Suretyship"). Two other types of disputes are discussed here.

Transfer of Real Estate

When a homeowner sells her house, the problem frequently crops up as to whether certain items in the home have been sold or may be removed by the seller. Is a refrigerator, which simply plugs into the wall, a fixture or an item of personal property? If a dispute arises, the courts will apply the three tests—annexation, adaptation, and intention. Of course, the simplest way of avoiding the dispute is to incorporate specific reference to questionable items in the contract for sale, indicating whether the buyer or the seller is to keep them.

Tenant’s Fixtures

Tenants frequently install fixtures in the buildings they rent or the property they occupy. A company may install tens of thousands of dollars worth of equipment; a tenant in an apartment may bolt a bookshelf into the wall or install shades over a window. Who owns the fixtures when the tenant’s lease expires? The older rule was that any fixture, determined by the usual tests, must remain with the landlord. Today, however, certain types of fixtures—known as tenant’s fixturesFixtures added to rental property that become property of the owner.—stay with the tenant. These fall into three categories: (1) trade fixtures—articles placed on the premises to enable the tenant to carry on his or her trade or business in the rented premises; (2) agricultural fixtures—devices installed to carry on farming activities (e.g., milling plants and silos); (3) domestic fixtures—items that make a tenant’s personal life more comfortable (carpeting, screens, doors, washing machines, bookshelves, and the like).

The three types of tenant’s fixtures remain personal property and may be removed by the tenant if the following three conditions are met: (1) They must be installed for the requisite purposes of carrying on the trade or business or the farming or agricultural pursuits or for making the home more comfortable, (2) they must be removable without causing substantial damage to the landlord’s property, and (3) they must be removed before the tenant turns over possession of the premises to the landlord. Again, any debatable points can be resolved in advance by specifying them in the written lease.

Key Takeaway

Personal property is often converted to real property when it is affixed to real property. There are three tests that courts use to determine whether a particular object has become a fixture and thus has become real property: annexation, adaptation, and intention. Disputes over fixtures often arise in the transfer of real property and in landlord-tenant relations.

Exercises

- Jim and Donna Stoner contract to sell their house in Rochester, Michigan, to Clem and Clara Hovenkamp. Clara thinks that the decorative chandelier in the entryway is lovely and gives the house an immediate appeal. The chandelier was a gift from Donna’s mother, “to enhance the entryway” and provide “a touch of beauty” for Jim and Donna’s house. Clem and Clara assume that the chandelier will stay, and nothing specific is mentioned about the chandelier in the contract for sale. Clem and Clara are shocked when they move in and find the chandelier is gone. Have Jim and Donna breached their contract of sale?

- Blaine Goodfellow rents a house from Associated Properties in Abilene, Texas. He is there for two years, and during that time he installs a ceiling fan, custom-builds a bookcase for an alcove on the main floor, and replaces the screening on the front and back doors, saving the old screening in the furnace room. When his lease expires, he leaves, and the bookcase remains behind. Blaine does, however, take the new screening after replacing it with the old screening, and he removes the ceiling fan and puts back the light. He causes no damage to Associated Properties’ house in doing any of this. Discuss who is the rightful owner of the screening, the bookcase, and the ceiling fan after the lease expires.